The Value of Play I: The Definition of Play Gives Insights

Freedom to quit is an essential aspect of play's definition..

Posted November 19, 2008 | Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

Play in our species serves many valuable purposes. It is a means by which children develop their physical, intellectual, emotional, social, and moral capacities. It is a means of creating and preserving friendships. It also provides a state of mind that, in adults as well as children, is uniquely suited for high-level reasoning, insightful problem solving, and all sorts of creative endeavors.

This essay is the first in a series I plan to post on The Value of Play . The subject of this first installment is the definition of play. Clues to play’s value lie in the definition.

Most of this essay is about the defining characteristics of play, but before listing them there are three general points that I think are worth keeping in mind. The first point is that the characteristics of play all have to do with motivation and mental attitude, not with the overt form of the behavior. Two people might be throwing a ball, or pounding nails, or typing words on a computer, and one might be playing while the other is not. To tell which one is playing and which one is not, you have to infer from their expressions and the details of their actions something about why they are doing what they are doing and their attitude toward it.

The second point, toward definition, is that play is not necessarily all-or-none. Play can blend with other motives and attitudes, in proportions ranging anywhere from 0 up to 100 percent play. Pure play occurs more often in children than in adults. In adults, play is commonly blended with other motives, having to do with adult responsibilities. That is why, in everyday conversation, we tend to talk about children “playing” and about adults bringing a “playful attitude” or “playful spirit” to their activities. We intuitively think of playfulness as a matter of degree. Of course, we don’t have meters for measuring these things, but I would estimate that my behavior in writing this blog is about 80% play.

The third point is that play is not neatly defined in terms of some single identifying characteristic. Rather, it is defined in terms of a confluence of several characteristics. People before me who have studied and written about play have, among them, described quite a few such characteristics; but they can all be boiled down, I think, to the following five:

- Play is self-chosen and self-directed.

- Play is activity in which means are more valued than ends.

- Play has structure, or rules, which are not dictated by physical necessity but emanate from the minds of the players.

- Play is imaginative, non-literal, mentally removed in some way from “real” or “serious” life.

- Play involves an active, alert, but non- stressed frame of mind.

The more fully an activity entails all of these characteristics, the more inclined most people are to refer to that activity as play. By “most people,” I don’t just mean most scholars who study play. Even young children are most likely to use the wordplay for activities that most fully contain these five characteristics. These characteristics seem to capture our intuitive sense of what play is. Notice that all of the characteristics have to do with the motivation or attitude that the person brings to the activity.

Let me elaborate on these characteristics, one by one, and expand a bit on each by pointing out some of its implications for thinking about the purposes of play.

1. Play is self-chosen and self-directed; players are always free to quit.

Play is, first and foremost, an expression of freedom. It is what one wants to do as opposed to what one is obliged to do. The joy of play is the ecstatic feeling of liberty. Play is not always accompanied by smiles and laughter , nor are smiles and laughter always signs of play; but play is always accompanied by a feeling of “Yes, this is what I want to do right now.” Players are free agents, not pawns in someone else’s game.

Players not only choose to play or not play, but they also direct their own actions during play. As I will argue below, play always involves rules of some sort, but all players must freely accept the rules, and if rules are changed then all players must agree to the changes. That is why play is the most democratic of all activities. In social play (play involving more than one player), one player may emerge for a period as the leader , but only at the will of all the others. Every rule a leader proposes must be approved, at least tacitly, by all of the other players.

The ultimate freedom in play is the freedom to quit. A person who feels coerced or pressured to engage in an activity, and unable to quit, is not a player but a victim. The freedom to quit provides the foundation for all of the democratic processes that occur in social play. If one player attempts to bully or dominate the others, the others will quit and the game will be over; so players who want to continue playing must learn not to bully or dominate. People who don’t agree to a proposed change in rules may likewise quit, and that is why leaders in play must gain the consent of the other players in order to change a rule. People who begin to feel that their needs or desires are not being met in play will quit, and that is why children learn, in play, to be sensitive to others’ needs and to strive to meet those needs. It is through social play that children learn, on their own, with no lectures, how to meet their own needs while, at the same time, satisfying the needs of others. This is perhaps the most important lesson that people in any society can learn.

This point about play being self-chosen and self-directed is ignored by, or perhaps unknown to, many adults who try to take control of children’s play. Adults can play with children, and in some cases can even be leaders in children’s play, but to do so requires at least the same sensitivity that children themselves show to the needs and wishes of all the players. Because adults are commonly viewed as authority figures, children often feel less able to quit, or to disagree with the proposed rules, when an adult is leading than when a child is leading. And so, when adults try to lead children’s play the result often is something that, for many of the children, is not play at all. When a child feels coerced, the play spirit vanishes and all of the advantages of that spirit go with it. Math games in school and adult-led sports are not play for those who feel that they have to participate and are not ready to accept, as their own, the rules that the adults have established. Adult-led games can be great for kids who freely choose them, but can seem like punishment to kids who haven’t made that choice.

What is true for children’s play is also true for adults’ sense of play. Research studies have shown that adults who have a great deal of freedom as to how and when to do their work often experience that work as play, even (in fact, especially) when the work is difficult. In contrast, people who must do just what others tell them to do at work rarely experience their work as play.

2. Play is an activity in which means are more valued than ends.

Many of our actions are “free” in the sense that we don’t feel that other people are making us do them, but are not free, or at least are not experienced as free, in another sense. These are actions that we feel we must do in order to achieve some necessary or much-desired goal, or end. We scratch an itch to get rid of the itch, flee from a tiger to avoid getting eaten, study an uninteresting book to get a good grade on a test, work at a boring job to get money. If there were no itch, tiger, test, or need for money, we would not scratch, flee, study, or do the boring work. In those cases we are not playing.

To the degree that we engage in an activity purely to achieve some end, or goal, which is separate from the activity itself, that activity is not play. What we value most, when we are not playing, are the results of our actions. The actions are merely means to the ends. When we are not playing, we typically opt for the shortest, least effortful means of achieving our goal. The non-playful, goal-oriented college student, for example, does the least studying in each course that she can in order to get the “A” that she desires, and her studying is focused directly on the goal of doing well on the tests. Any learning not related to that goal is, for her, wasted effort.

In play, however, all this is reversed. Play is activity conducted primarily for its own sake. The playful student enjoys studying the subject and cares less about the test. In play, attention is focused on the means, not the ends, and players do not necessarily look for the easiest routes to achieving the ends. Think of a cat preying on a mouse versus a cat that is playing at preying on a mouse. The former takes the quickest route for killing the mouse. The latter tries various ways of catching the mouse, not all very efficient, and lets the mouse go each time so it can try again. The preying cat enjoys the end; the playing cat enjoys the means. (The mouse, of course, enjoys none of this.)

Play often has goals, but the goals are experienced as an intrinsic part of the game, not as the sole reason for engaging in the game’s actions. Goals in play are subordinate to the means for achieving them. For example, constructive play (the playful building of something) is always directed toward the goal of creating the object that the player has in mind. But notice that the primary objective in such play is the creation of the object, not the having of the object. Children making a sandcastle would not be happy if an adult came along and said, "You can stop all your effort now. I'll make the castle for you." That would spoil their fun. The process, not the product, motivates them. Similarly, children or adults playing a competitive game have the goal of scoring points and winning, but, if they are truly playing, it is the process of scoring and trying to win that motivates them, not the points themselves or the status of having won. If someone would just as soon win by cheating as by following the rules, or get the trophy and praise through some shortcut that bypasses the game process, then that person is not playing.

Adults can test the degree to which their work is play by asking themselves this: “If I could receive the same pay, the same prospects for future pay, the same amount of approval from other people, and the same sense of doing good for the world for not doing this job as I am receiving for doing it, would I quit?” If the person would eagerly quit, the job is not play. To the degree that the person would quit reluctantly, or not quit, the job is play. It is something that the person enjoys independently of the extrinsic rewards received for doing it.

One reason why play is such an ideal state of mind for creativity and learning is because the mind is focused on means. Since the ends are understood as secondary, fear of failure is absent and players feel free to incorporate new sources of information and to experiment with new ways of doing things.

3. Play is guided by mental rules.

Play is freely chosen activity, but it is not freeform activity. Play always has structure, and that structure derives from rules in the player’s mind. This point is really an extension of the point just made about the importance of means in play. The rules of play are the means. To play is to behave in accordance with self-chosen rules. The rules are not like rules of physics, nor like biological instincts, which are automatically followed. Rather, they are mental concepts that often require conscious effort to keep in mind and follow.

A basic rule of constructive play, for example, is that you must work with the chosen medium in a manner aimed at producing or depicting some specific object or design. You don’t just pile up blocks randomly; you arrange them deliberately in accordance with your mental image of what you are trying to make. Even rough and tumble play (playful fighting and chasing), which may look wild from the outside, is constrained by rules. An always-present rule in play fighting, for example, is that you mimic some of the actions of real fighting, but you don’t really hurt the other person. You don’t hit with all your force (at least not if you are the stronger of the two); you don’t kick, bite, or scratch. Play fighting is much more controlled than real fighting; it is always an exercise in restraint.

Among the most complex forms of play, in terms of rules, is what play researchers call sociodramatic play—the playful acting out of roles or scenes, as when children are playing “house,” or acting out a marriage , or pretending to be superheroes. The fundamental rule here is that you must abide by your and the other players’ shared understanding of the role that you are playing. If you are the pet dog in a game of “house,” you must walk around on all fours and bark rather than talk. If you are Wonder Woman, and you and your playmates believe that Wonder Woman never cries, then you refrain from crying, even when you fall down and hurt yourself.

To illustrate the rule-based nature of sociodramatic play, the Russian psychologist Lev Vygotsky wrote about two actual sisters—ages seven and five—who sometimes played that they were sisters.[1] As actual sisters, they rarely thought about their sisterhood and had no consistent way of behaving toward one another. Sometimes they enjoyed one another, sometimes they argued, and sometimes they ignored one another. But, when they were playing sisters, they always behaved according to their shared stereotype of how sisters should behave. They dressed alike, talked alike, always loved one another, talked about the differences between themselves and everyone else, and so on. Much more self-control , mental effort, and rule following was involved in playing sisters than in being sisters.

The category of play with the most explicit rules is that called formal games. These are games, like checkers and baseball, with rules that are specified, verbally, in ways designed to minimize ambiguity in interpretation. The rules of these games are commonly passed along from one generation of players to the next. Many formal games in our society are competitive, and one purpose of the formal rules is to make sure that the same restrictions apply equally to all competitors. Players of formal games, if they are true players, must adopt these rules as their own for the period of the game and be willing to stick to them. Of course, except in “official” versions of such games, players commonly modify the rules to fit their own needs, but each modification must be agreed upon by all the players.

The main point I want to make here is that every form of play involves a good deal of self-control. When not playing, children (and adults too) may act according to their immediate biological needs, emotions, and whims; but in play they must act in ways that they and their playmates deem appropriate to the game. Play draws and fascinates the player precisely because it is structured by rules that the player herself or himself has invented or accepted.

The student of play who most strongly emphasized play’s rule-based nature was Lev Vygotsky, whose example of sisters playing sisters I just mentioned. In an essay on the role of play in development, originally published in 1933, Vygotsky commented, as follows, on the apparent paradox between the idea that play is spontaneous and free and the idea that players must follow rules:

“The … paradox is that in play [the child] adopts the line of least resistance—she does what she most feels like doing because play is connected with pleasure—and at the same time she learns to follow the line of greatest resistance by subordinating herself to rules and thereby renouncing what she wants, since subjection to rules and renunciation of impulsive action constitute the path to maximum pleasure in play. Play continually creates demands on the child to act against immediate impulse. At every step the child is faced with a conflict between the rules of the game and what she would do if she could suddenly act spontaneously. … Thus, the essential attribute of play is a rule that has become a desire. …. The rule wins because it is the strongest impulse. Such a rule is an internal rule, a rule of self-restraint and self-determination …. In this way a child’s greatest achievements are possible in play, achievements that tomorrow will become her basic level of real action and morality .”[1]

Vygotsky's point, of course, is that the child's desire to play is so strong that it becomes a motivating force for learning self-control. The child resists impulses and temptations that would run counter to the rules because the child seeks the larger pleasure of remaining in the game. To Vygotsky's analysis, I would add that the child accepts and desires the rules of play only because he or she is always free to quit if the rules become too burdensome. With that in mind, the paradox can be seen to be superficial. The child's real-life freedom is not restricted by the rules of the game, because the child can at any moment choose to leave the game. That is another reason why the freedom to quit is such a crucial aspect of the definition of play. Without that freedom, rules of play would be intolerable. To be required to act like Wonder Woman in real life would be terrifying, but to act like that in play––a realm you are always free to leave––is great fun.

Along with Vygotsky, I would contend that the greatest of play’s many values for our species lies in the learning of self-control. Self-control is the essence of being human. We commonly say that people behave like “animals,” rather than like humans, when they fail to abide by socially agreed-upon rules and, instead, impulsively follow their immediate drives and whims. Everywhere, to live in human society, people must behave in accordance with conscious, shared mental conceptions of what is appropriate; and that is what children practice constantly in their play. In play, from their own desires, children practice the art of being human.

4. Play is non-literal, imaginative, marked off in some way from reality.

Another apparent paradox of play, also pointed out by Vygotsky, is that play is serious yet not serious, real yet not real. In play one enters a realm that is physically located in the real world, makes use of props in the real world, is often about the real world, is said by the players to be real, and yet in some way is mentally removed from the real world.

Imagination , or fantasy , is most obvious in sociodramatic play, where the players create the characters and plot, but it is also present to some degree in all other forms of human play. In rough and tumble play, the fight is a pretend one, not a real one. In constructive play, the players say that they are building a castle, but they know it is a pretend castle, not a real one. In formal games with explicit rules, the players must accept an already established fictional situation that provides the foundation for the rules. For example, in the real world bishops can move in any direction they choose, but in the fantasy world of chess they can move only on the diagonals.

The fantasy aspect of play is intimately connected to play’s rule-based nature. Because play takes place in a fantasy world, it must be governed by rules that are in the minds of the players rather than by laws of nature. In reality, one cannot ride a horse unless a real horse is physically present; but in play one can ride a horse whenever the game's rules permit or prescribe it. In reality, a broom is just a broom, but in play it can be a horse. In reality, a chess piece is just a carved bit of wood, but in chess it is a bishop or a knight that has well-defined capacities and limitations for movement that are not even hinted at in the carved wood itself. The fictional situation dictates the rules of the game; the actual physical world within which the game is played is secondary. Through play the child learns to take charge of the world and not simply respond passively to it. In play the child’s mental concept dominates, and the child molds available elements of the physical world to meet that concept.

Play of all sorts has “time in” and “time out,” though that is more obvious for some forms of play than others. Time in is the period of fiction. Time out is the temporary return to reality—perhaps to tie one’s shoes, or go to the bathroom, or correct a playmate who hasn't been following the rules. During time in one does not say, “I am just playing,” any more than does Shakespeare’s Hamlet announce from the stage that he is merely pretending to murder his stepfather.

Adults sometimes become confused by the seriousness of children’s play and by children’s refusal, while playing, to say that they are playing. They worry needlessly that children don’t distinguish fantasy from reality. When my son was four years old he was Superman for periods that sometimes lasted more than a day. During those periods he would deny vigorously that he was only pretending to be Superman, and this worried his nursery school teacher. She was only partly mollified when I pointed out that he never attempted to leap off of actual tall buildings or stop real railroad trains and that he would acknowledge that he had been playing when he finally did declare time out by removing his cape. To acknowledge that play is play is to remove the magic spell; it automatically turns time in into time out.

An amazing fact of human nature is that even 2-year-olds know the difference between real and pretend. A 2-year-old who turns a cup filled with imaginary water over a doll and says, “Oh oh, dolly all wet,” knows that the doll isn’t really wet. It would be impossible to teach such young children such a subtle concept as pretense, yet they understand it. Apparently, the fictional mode of thinking, and the ability to keep that mode distinct from the literal mode, are innate to the human mind. That innate capacity is part of the inborn capacity for play.

The fantasy element of play is often not as obvious, or as full-blown, in adults’ play as in children’s play. That is one reason why adults’ play is typically not of the 100% variety. Yet, I would argue, fantasy occupies a big role in much if not most of what adults do and is a major element in our intuitive sense of the degree to which adult activities are play. An architect designing a house is designing a real house. Yet, the architect brings a good deal of imagination to bear in visualizing the house, imagining how people might use it, and matching it with some aesthetic concepts that she has in mind. It is reasonable to say that the architect builds a pretend house, in her mind and on paper, before it becomes a real one.

When I say that my writing this blog is about 80% play, I am taking into account not only my sense of freedom about doing it, my enjoyment of the process, and the fact that I’m following rules (about writing) that I accept as my own, but also the fact that a considerable degree of imagination is involved. I’m not making up the facts, but I am making up the way of stringing them together, and I am imagining how you might respond to what I am writing. Sometimes my fantasy goes even further, and I imagine that the ideas I’m presenting will have certain positive effects on society. So, fantasy is moving me along in this, much as it moves a child along in building a sandcastle or pretending to be Superman. The fact that parts of my fantasy could possibly turn into reality does not negate its status as fantasy.

5. Play involves an active, alert, but non-stressed frame of mind.

This final characteristic of play follows naturally from the other four. Because play involves conscious control of one’s own behavior, with attention to process and rules, it requires an active, alert mind. Players do not just passively absorb information from the environment , or reflexively respond to stimuli, or behave automatically in accordance with habit. Moreover, because play is not a response to external demands or immediate strong biological needs, the person at play is relatively free from the strong drives and emotions that are experienced as pressure or stress. And because the player’s attention is focused on process more than outcome, the player’s mind is not distracted by fear of failure. So, the mind at play is active and alert, but not stressed. The mental state of play is what some researchers call “flow.” Attention is attuned to the activity itself, and there is reduced consciousness of self and time. The mind is wrapped up in the ideas, rules, and actions of the game.

This point about the mental state of play is very important for understanding play’s value as a mode of learning and creative production. The alert but unstressed condition of the playful mind is precisely the condition that has been shown repeatedly, in many psychological experiments, to be ideal for creativity and the learning of new skills. Such experiments are normally not described as experiments on play, but it is no stretch to interpret them as that. What the experiments show is that strong pressure to perform well (which induces a non-playful state) improves performance on tasks that are mentally easy or habitual for the person, but worsens performance on tasks that require creativity, or conscious decision making , or the learning of new skills. In contrast, anything that is done to reduce the person’s concern with outcome and to increase the person’s enjoyment of the task for its own sake—that is, anything that increases playfulness—has the opposite effect.

Strong pressure to perform well inhibits creativity and learning by focusing attention strongly and narrowly on the goal, thereby reducing the ability to focus on means. In the pressured state, one tends to fall back on instinctive or well-learned ways of doing things. That way of responding to pressure is adaptive in many emergency situations. When a tiger is chasing you, you use whatever means you have already learned for getting away or hiding; that is not a good time to experiment with new ways. Experts in any realm can usually perform well in the pressured state because they can call on their well-learned, habitual modes of responding and don’t need to learn anything new or act creatively. Their attention can focus on producing the best possible outcome using the repertoire of actions that are already second nature to them.

When we pressure students to do well on their schoolwork by constantly evaluating their work, we put them into a non-playful, goal-directed state that may motivate those who already know how to do it to perform well, but inhibits experimentation and learning in those who don’t already know how. Pressure widens the performance gap between experts and novices. Even experts, though, must play at their activity of expertise if they are going to rise to still higher levels of expertise. And, in some realms, such as art and essay writing, creativity is required no matter how much experience a person has had, and a playful mind always performs best in those realms.

When an activity becomes so easy, so habitual, that it no longer requires conscious mental effort, it may lose its status as play. That is why players keep making the game harder, or different, or keep raising the criteria for success. A game is a game only if an active, alert mind is required to do it well.

Does this extended definition of play make sense to you? Does it fit with the way that you think of play in everyday life? I ask this question genuinely. I want, for my own work, to be sure that I am using a concept of play that fits with the concept of play that people find useful in everyday discourse. I would very much appreciate your comments on this.

As I said, over the next few weeks I will be elaborating on the various functions of play, both for children and for adults, and I will refer from time to time to the definition of play that I have provided in this post. Stay tuned.

And now, what do you think about this? … This blog is, in part, a forum for discussion. Your questions, thoughts, stories, and opinions are treated respectfully by me and other readers, regardless of the degree to which we agree or disagree. Psychology Today no longer accepts comments on this site, but you can comment by going to my Facebook profile, where you will see a link to this post. If you don't see this post at the top of my timeline, just put the title of the post into the search option (click on the three-dot icon at the top of the timeline and then on the search icon that appears in the menu) and it will come up. By following me on Facebook you can comment on all of my posts and see others' comments. The discussion is often very interesting.

Lev S. Vygotsky, “The Role of Play in Development,” in M. Cole, V. John-Steiner, S. Scribner, & E. Souberman (Eds.). Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes , 92-104. (1978, original essay published in 1933).

Peter Gray, Ph.D. , is a research professor at Boston College, author of Free to Learn and the textbook Psychology (now in 8th edition), and founding member of the nonprofit Let Grow.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

At any moment, someone’s aggravating behavior or our own bad luck can set us off on an emotional spiral that threatens to derail our entire day. Here’s how we can face our triggers with less reactivity so that we can get on with our lives.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

About The Education Hub

- Course info

- Your courses

- ____________________________

- Using our resources

- Login / Account

What is play and why is it important for learning?

- Videos of practice >

- Communication & oral language

- Curriculum design

- Early literacy

- Early mathematical thinking

- Science & STEM

- Social & emotional competence

- Visual arts

- Working theories

- Culturally responsive practice

- Digital technologies

- Infants and toddlers

- Intentional teaching

- Philosophical approaches

- Relational pedagogies

- Social justice & children’s rights

Learning & development

- Child development

- Executive function

- Movement and learning

- Neurodiversity

- Trauma-informed practice

- Building effective teams

- Leadership

Relationships

- Parent & whānau relationships

- Transitions

Children & wellbeing

- Learner identity

Environments

- Indoor spaces

- Outdoor spaces

- Learning stories

Professional development

- Teacher inquiry

- Intentional Teaching Practices for Early Mathematics Course

- Visual Arts in ECE Course

- Social Emotional Competence Course

- Early Literacies Course

- Infants & Toddlers Course

- NEW: Leadership series

- Leadership 1: Leading Authentically

- Leadership 2: Leading People & Teams

- Leadership 3: Leading Partnerships & Collaborations

- Leadership 4: Leading Curriculum, Pedagogy & Innovation

- Leadership 5: Leading Improvement

- Assessment & Intentional Teaching Course

Access your courses through your Account section

- Videos of practice

What is play?

Play is multi-faceted, complex and dynamic, eluding easy definition. It is usually felt to be a universal activity and children are often portrayed as having an inherent desire and capacity to play.

Play has been defined as an activity that is:

- characterised by engagement and engagement, with high levels of involvement, engrossment and intrinsic motivation

- imaginative, creative, and non-literal

- voluntary or freely chosen, personally directed (often child-initiated) and free from externally imposed rules

- fluid and active but also guided by mental rules and high levels of metacognition and metacommunication (communication about communication) which give it structure

- process-driven rather than product-driven, with no extrinsic goals

Play can take different forms, with common categories that can and do overlap within an given episode of play. These include exploratory play with objects, physical play, pretend, fantasy or dramatic play, games and puzzles and other play involving explicit rules, constructive play (including artistic and musical play), language play (play with words and other features of language such as rhyme) and outdoor play.

Play can also be categorised in relation to the relative amount of power and control afforded to the players:

- Free or ‘pure’ play: Children have all the control, and adults are passive observers

- Guided play: Teacher-child collaboration, with the child’s interests foregrounded

- Playful teaching: The teacher is in charge

These three kinds of play are associated with different outcomes and are relevant to teachers in determining the kinds of play, or combinations of kinds of play, to offer within school and early childhood settings.

What is free play?

Free play is child-initiated and child-directed. Children choose their activities and focus, enabling unconstrained freedom of expression and open-ended interactions with their environment. Play is initiated, sustained and developed by children, free of adult influence, although this does mean that it focuses on ideas, content and language that are already familiar and known to children. Some researchers question the extent to which free play is truly free, as children’s choices about what, how, where and with whom to play may be influenced by the play environment and its associated rules and boundaries (which are controlled by adults), and the choices of others about what to play. Gender, ethnicity, social class and disability may also affect their patterns of participation.

What is guided play?

Guided play (also called ‘scaffolded play’ or ‘mutually directed’ play) is child-centred and goal-directed. Guided play invites children’s active engagement, free exploration and direction of play, but also has clear learning goals so that play behaviours are limited in useful ways and distraction is reduced. Children’s initiatives, reflections, choices, and creativity are important as a context for teachers to extend children’s knowledge, understanding and skills. They allow teachers to naturally integrate desired learning outcomes with children’s play and infuse play with new and unfamiliar content and ideas. Teachers are sensitive and responsive to children’s interests and interactions while maintaining a focus on learning goals through deliberate, purposeful, and intentional teaching strategies. These might include commenting on discoveries, offering feedback, demonstrating use of equipment, reinforcing specific vocabulary or helping the child explore new strategies for problem-solving, within the context of the activities that children are constructing.

Teachers also initiate and co-construct play with children. They might design a learning activity that incorporates a child’s specific interest, or choose themes and contexts for dramatic play that is based on children’s interests or significant events and links to specific learning objectives. Teachers and children collaboratively design the context of the play, including the theme and its resources, and then children develop their play within the rules and actions of that context.

What is teacher-directed play?

Teacher-directed play involves teacher-determined activities, outcomes and modes of engagement. Teachers use a playful, engaging manner to develop children’s academic skills and knowledge, focusing on playful learning processes, fun and enjoyment, and the use and development of children’s creativity to invite children’s active engagement. However, unlike free and guided play, teachers retain tight control over what occurs, outlining specific rules of play for children to follow, specifying how children are expected to engage in the activities, and generally structuring activities within a given time frame to ensure specific learning outcomes.

The development of play

During early childhood, children’s play becomes increasingly complex, involving high levels of organisation and requiring increasingly sophisticated social, physical and cognitive skills. Although all children engage in a range of different play types, some are more prevalent at different ages. Infants and toddlers engage in exploratory and social play (such as ‘peek-a-boo’). Exploration precedes play, and is a time of gathering information and discovering the properties and attributes of an object, situation or idea. Toddlers develop ‘functional play’ involving the repetition of particular physical actions and early pretend play.

With the development of imagination, older children engage in constructive play, pretend play and language play. They demonstrate increasing problem-solving skills, language, and collaboration, and show increased attention to processes, structures, and outcomes. They are highly intentional in their activity, and better able to combine and use materials in more complex ways. Sociodramatic play, involving cooperation and the coordination of play between two or more children, usually begins when children are 4 or 5 years old, and is cognitively demanding as children simultaneously hold in mind what they have negotiated for their role and character, the other children’s characters and what has been agreed as the plot, as well as what different objects represent.

Does play lead to effective learning?

Research into the effectiveness of play for supporting children’s learning is complex, given contrasting definitions and conceptualisations of play and its different types, the overlap between play types, and outside influences on play such as the environment or structuring and involvement of adults. Play is a complex activity with many integrated dimensions that each have a potential impact on children’s outcomes, making it difficult to separate out play as an influence on learning. Play may include particular kinds of adult interactions, or engage children in specific content, and it may be these features of children’s play that are responsible for learning gains, rather than play itself.

The current research does not make it possible to determine whether play is crucial to development, whether it is merely one way to promote development alongside others which may work as well or even better, or whether play is a byproduct of other capacities that are the actual source of children’s learning and development, such as social intelligence or language skill. Many studies of the impact of play on learning are found to have methodological weaknesses and there is a lack of replication of findings between studies that have small and relatively homogeneous samples. Some of the research findings directly conflict each other, and lead to opposing recommendations for practice.

However, much of the research concludes that play is a powerful learning mode and central to children’s learning. Play integrates children’s experiences, knowledge and representations in order to help them create meaning and sense and to understand the world. Pretending requires children to think of things that are not actually present, a skill required in many learning and life situations. The impact of play is multifaceted, supporting cognitive, emotional, social and physical development including:

- Benefits for well-being , including higher self-efficacy, higher expectations for one’s success, intrinsic motivation, and positive attitudes towards the early childhood setting or school.

- Academic/cognitive benefits : play supports exploratory skills and discovery, the use of abstract thought and symbols, communication and oral language skills, verbal intelligence, imagination and creativity, and reading, writing and mathematics. Play also encourages important learning dispositions, engagement and participation and the integration of different cognitive processes. Play develops self-regulatory executive function skills (such as controlling attention, suppressing impulses, flexibly redirecting thought and behaviour, and holding and using information in working memory), metacognitive skills and problem-solving.

- Social and emotional benefits including social skills such as making friends, empathy, expressing emotion, and conflict resolution. Play can also build resilience.

- Physical benefits in terms of the development of large and small body muscles and motor skills, while the physicality of play is associated with improved cognitive function, behavioural and cognitive control, and academic achievement.

Is one kind of play pedagogy more clearly linked to positive outcomes?

Both free play and more guided and directed approaches are found to foster achievement. In general, research that focuses on developmental outcomes finds free play significant, whereas research that focuses on academic outcomes finds guided and teacher-directed play more effective. However, some research comparing play-based approaches finds no significant difference in children’s learning through free play, guided play and teacher-directed play.

Free play has been found to support a number of more general learning outcomes. It supports:

- socioemotional development, particularly self-regulation, and social skills

- creativity and imagination

- problem-solving and persistence

- engagement in literacy activities (where literacy materials are embedded in play scenarios and environments)

- general cognitive development (through activities such as planning, problem-solving and comprehension)

Free play may be less useful for learning content, developing key concepts, or for supporting children to focus on important dimensions of new learning. Free play can vary in quality, lack challenge and limit learning opportunities. The research suggests that free play, while still important for a range of less measurable outcomes, is best complemented by high quality scaffolded and guided play in which teachers are involved.

Research indicates that guided discovery approaches are more effective than free or unassisted play for supporting more specific learning outcomes. Guided play is found to

- better support science learning, and language, literacy and mathematics outcomes

- improve vocabulary and support greater engagement in social interactions

- foster literacy and mathematics skills and general learning of content

- support higher levels of creative and flexible exploration and more effective problem-solving

- improve self-regulation skills such as inhibitory control and cognitive flexibility

Teacher-directed play in the form of carefully designed and challenging activities that include free choice, practical and intrinsically motivating tasks, and peer interactions is consistently associated with positive outcomes. Research reports that teacher-directed play:

- supports literacy skills, mathematics and general academic learning

- improves children’s mathematical learning gains (with greater gains for children learning through card and board games than children experiencing more formal training)

- increases children’s affect and engagement through the addition of a play component to learning experiences

Overall, child-centred and playful learning approaches are more likely to foster academic improvements that are sustained than traditional, formal approaches, but some research finds that children are more likely to learn content in teacher-led contexts. It is important to consider the information and skills to be learned when determining the most effective approach for learning through play.

A note of caution: Critical views on the use of play pedagogies

While there is much rhetoric around the importance of play for young children’s learning, in these discourses play can sometimes be romanticised, while descriptions of play in curriculum documents can be reductive and fail to acknowledge the complexity of children’s play experiences.

Some researchers critique the elevated status of play as a pedagogy for learning. They argue that:

- Learning can be supported in diverse ways , and play need not form the only catalyst for learning. Play is a cultural phenomena that is highly dependent on adult mediation and engagement. Where adults encourage pretending and other playful forms, children engage in these behaviours, but in other contexts where pretending and play are not encouraged, children learn in other ways, such as through real life tasks, storytelling, and organised games.

- Children’s play repertoires and experiences vary , and richly resourced, free play environments that reflect Western perspectives on play may not resonate with culturally diverse families. Children may be disadvantaged by approaches that emphasise independence, self management and free choice if these are inconsistent with home expectations, or if they have limited prior experience of play themes or the complex social processes required.

- Children may not be able to express their interests and needs through play activities . The freedom to choose may offer some children an advantage over others.

- Play is not value-neutral . Because of the unequal power relations between teachers and children, play can never be ‘free’. The use of play as pedagogy for the early years privileges particular (Western) constructs about children and ways of learning, in terms of ideas about appropriate play, which are then used to regulate children’s behaviour. In these ways play reinforces children’s positioning within social hierarchies including those of gender and race.

- Play can be cruel , involving teasing, pranks and playing tricks. It can also be characterised by self-interest, and exploitation and manipulation of situations, which is another way in which some children can experience loss of agency.

Further Reading

Gray, P. (2017). What exactly is play, and why is it such a powerful vehicle for learning? Top Language Disorders, 37(3), 217-228.

Hirsch-Pasek, K. & Golinkoff, R. M. (2008). Why play = learning. In R.E. Tremblay, M. Boivin, & R.D. Peters (Eds), Encyclopedia of Early Childhood Development. Quebec, Canada: Centre of Excellence for Early Childhood Development and Strategic Knowledge. Retrieved from http://www.child-encyclopedia.com/documents/Hirsh-Pasek-GolinkoffANGxp.pdf .

Weisberg, D. S., Hirsh-Pasek, K. & Golinkoff, R. M. (2013). Guided play: Where curricular goals meet a playful pedagogy. Mind, Brain and Education 7 (2), 104-112.

White, J., O’Malley, A., Toso, M., Rockel, J., Stover, S., & Ellis, F. (2007). A contemporary glimpse of play and learning in Aotearoa New Zealand. International Journal of Early Childhood, 39 (1), 93-105.

Dr Vicki Hargraves

Vicki runs our ECE webinar series and also is responsible for the creation of many of our ECE research reviews. Vicki is a teacher, mother, writer, and researcher living in Marlborough. She recently completed her PhD using philosophy to explore creative approaches to understanding early childhood education. She is inspired by the wealth of educational research that is available and is passionate about making this available and useful for teachers.

Download this resource as a PDF

Please provide your email address and confirm you are downloading this resource for individual use or for use within your school or ECE centre only, as per our Terms of Use . Other users should contact us to about for permission to use our resources.

Interested in * —Please choose an option— Early childhood education (ECE) Schools Both ECE and schools I agree to abide by The Education Hub's Terms of Use.

Did you find this article useful?

If you enjoyed this content, please consider making a charitable donation.

Become a supporter for as little as $1 a week – it only takes a minute and enables us to continue to provide research-informed content for teachers that is free, high-quality and independent.

Become a supporter

Get unlimited access to all our webinars

Buy a webinar subscription for your school or centre and enjoy savings of up to 25%, the education hub has changed the way it provides webinar content, to enable us to continue creating our high-quality content for teachers., an annual subscription of just nz$60 per person gives you access to all our live webinars for a whole year, plus the ability to watch any of the recordings in our archive. alternatively, you can buy access to individual webinars for just $9.95 each., we welcome group enrolments, and offer discounts of up to 25%. simply follow the instructions to indicate the size of your group, and we'll calculate the price for you. , unlimited annual subscription.

- All live webinars for 12 months

- Access to our archive of over 80 webinars

- Personalised certificates

- Group savings of up to 25%

The Education Hub’s mission is to bridge the gap between research and practice in education. We want to empower educators to find, use and share research to improve their teaching practice, and then share their innovations. We are building the online and offline infrastructure to support this to improve opportunities and outcomes for students. New Zealand registered charity number: CC54471

We’ll keep you updated

Click here to receive updates on new resources.

Interested in * —Please choose an option— Early childhood education (ECE) Schools Both ECE and schools

Follow us on social media

Like what we do please support us.

© The Education Hub 2024 All rights reserved | Site design: KOPARA

- Terms of use

- Privacy policy

Privacy Overview

Thanks for visiting our site. To show your support for the provision of high-quality research-informed resources for school teachers and early childhood educators, please take a moment to register.

Thanks, Nina

- Skip to main content

- Skip to secondary menu

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

Study Today

Largest Compilation of Structured Essays and Exams

Essay on Importance of Play for Children and Students

January 21, 2018 by Study Mentor Leave a Comment

Life is vast. Life is complex. Life is sublime. To sail through the complexities of life we always need quality time. In all these hurdles, obstacles of life playing keeps us alive, young. It plays the vital part in our life. Without it life becomes dull, boring.

Play makes us feel enthusiastic about life. When we talk about play the words like revitalization, freshness, rejuvenation comes to our mind. Playing is something that while doing it we find ourselves away from all the hindrances, obstructions and obstacles of life.

Table of Contents

Definition of play in today’s world

Play has been an integral part of human life as playing gives us enthusiasm to enjoy life. The type of play we used to play has been changed throughout the time, but playing has been still a significant part of our life.

The type of playing we used to play included jumping around, hopping and the play which children used to play without any goal or motive just for fun every day. That kind of playing were called free play without observation of anyone. Free plays were unorganized.

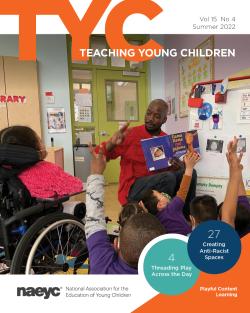

Image Credit: Source

In today’s modern world the cities have become more crowded, the people have become more career oriented, the safety has become a concerning issue and time has been of limited source. Nowadays play includes art lesson, music lesson, sports coaching etc. that boosts confidence and enhances social skills.

The type of playing is no more of free play because it is not about only fun but also about taking steps towards goal. Parents are also preferring this kind of play over free play because it involves physical goods with mental and practical benefits and safety of children.

Play in our modernized world has no age limit. Almost all age group are involved in play.

“Play is the highest form of research” – Albert Einstein

Play as an integral part of childhood

“Play is so integral to childhood that a child who does not have the opportunities to play is cut off from a major portion of childhood.”

As we have mentioned earlier that play holds an important key factor in a child’s life and play no more involves free play. Play with motive is good but free play shapes a child in way more than we can imagine.

Children should indulge free play as it makes them more imaginative, innovative without any pressure and improves brain function as children think, interact, meet, laugh with each other. Playing improves the power to focus.

Playing ameliorates the learning process of a child as it involves most of the brain work with an enjoyable environment. By playing children learn. In our modernized world parents think that education should be the highest priority for their children.

In this cut throat competitive world, they are forgetting the fact that play is the practical way of learning. In a recent study it is found that kids do better learn while they have given recess. Play enhances emotional growth and makes more sociable. It is the main factor for building self-esteem and self-confidence.

“Do not keep children to their studies by compulsion but by play” – Plato

Importance of play for an Adult

“ We don’t stop playing because we grow old; we grow old because we stop playing.”

The above saying holds the truth as most people think that playing is only for children and there should be age limit to play. It is also true that play is a work of child. In our hectic environment to feel young and alive we should bring the child among ourselves. Play makes us enthusiastic and lively by bringing the child in us.

As an adult, people stick to television sets or smartphones to relieve stress. But this is the worst way to relieve ourselves from hectic environment and to have a healthy body as our body needs movement and mind needs cheerfulness. Play is the best way for relaxation and enjoying yourself free from all work and tight schedule.

Playing improves the productivity in work as it stimulates the brain function and builds emotional growth. It is found that most of the companies are also introducing leisure time and indoor plays for their employees.

Play as a key factor for sound health

“A sound mind resides in a sound body.”

A person needs strong body and mind to fulfill the purpose of life. A mentally or physically weak person cannot achieve the goal in life. Life becomes burden for a sick person. Wealth or power cannot make a person happy without mental or physical well being.

Playing increases the power of concentration and tolerance. Playing relieves stress which makes us mentally strong. It builds the immune system strong resistance to diseases.

People do intense workouts to have a sound body. Instead of doing intense workouts playing is far better as it involves pure fun and creativity. As we live in a world of tightly scheduled, workaholic environment to feel stressed and feverish is unavoidable. Playing enhances the ability to withstand the pain.

Playing vital for social and emotional growth

“You can discover more about a person in an hour of play than in a year of conversation.”

As human beings are called social beings, we cannot live without being sociable or to live alone. So, it is important for us to be amiable with others. Playing involves activities like meeting, sharing, trusting, interacting, laughing with each other. Be it a child or an adult everyone needs to play as it

involves the above activities which are the main factors for social growth. Fun, laughing, sharing activities makes the relationship bonds stronger. A playful and friendly nature helps to make new friends, to build business relationships. Playing in groups is a practical fun way of group activities which teaches us how to coordinate and leadership qualities.

“Have regular hours for work and play; make each day both useful and pleasant.”

Reader Interactions

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Top Trending Essays in March 2021

- Essay on Pollution

- Essay on my School

- Summer Season

- My favourite teacher

- World heritage day quotes

- my family speech

- importance of trees essay

- autobiography of a pen

- honesty is the best policy essay

- essay on building a great india

- my favourite book essay

- essay on caa

- my favourite player

- autobiography of a river

- farewell speech for class 10 by class 9

- essay my favourite teacher 200 words

- internet influence on kids essay

- my favourite cartoon character

Brilliantly

Content & links.

Verified by Sur.ly

Essay for Students

- Essay for Class 1 to 5 Students

Scholarships for Students

- Class 1 Students Scholarship

- Class 2 Students Scholarship

- Class 3 Students Scholarship

- Class 4 Students Scholarship

- Class 5 students Scholarship

- Class 6 Students Scholarship

- Class 7 students Scholarship

- Class 8 Students Scholarship

- Class 9 Students Scholarship

- Class 10 Students Scholarship

- Class 11 Students Scholarship

- Class 12 Students Scholarship

STAY CONNECTED

- About Study Today

- Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

Scholarships

- Apj Abdul Kalam Scholarship

- Ashirwad Scholarship

- Bihar Scholarship

- Canara Bank Scholarship

- Colgate Scholarship

- Dr Ambedkar Scholarship

- E District Scholarship

- Epass Karnataka Scholarship

- Fair And Lovely Scholarship

- Floridas John Mckay Scholarship

- Inspire Scholarship

- Jio Scholarship

- Karnataka Minority Scholarship

- Lic Scholarship

- Maulana Azad Scholarship

- Medhavi Scholarship

- Minority Scholarship

- Moma Scholarship

- Mp Scholarship

- Muslim Minority Scholarship

- Nsp Scholarship

- Oasis Scholarship

- Obc Scholarship

- Odisha Scholarship

- Pfms Scholarship

- Post Matric Scholarship

- Pre Matric Scholarship

- Prerana Scholarship

- Prime Minister Scholarship

- Rajasthan Scholarship

- Santoor Scholarship

- Sitaram Jindal Scholarship

- Ssp Scholarship

- Swami Vivekananda Scholarship

- Ts Epass Scholarship

- Up Scholarship

- Vidhyasaarathi Scholarship

- Wbmdfc Scholarship

- West Bengal Minority Scholarship

- Click Here Now!!

Mobile Number

Have you Burn Crackers this Diwali ? Yes No

Why Play Is Important for Your Child’s Learning and Growth

- August 17, 2021

Play is more than just fun and games: It’s vital to a child’s learning and growth.

But it’s not always easy for a child to have time for spontaneous, unguided play, especially with other children. Some children are limited by the geography of where they live. Many families have busy schedules packed with pre-planned activities. It can be hard for a child to get time for unstructured play with peers.

We’ll look at why play is so important, as well as how playdates can help you make sure your child gets to spend time in unstructured play.

Why Is Play Important for Children?

First of all, play is just plain fun. But more than that, play is an important part of a child’s mental and social development. Playing with other children helps build a child’s brain, and is also good for their physical development.[1]

While playing, children can improve their strength, muscle control, and coordination. They also learn to try new things and take risks, which can help them in other aspects of life.[2]

There are specific elements of play among children—social play—that are particularly helpful to your child’s social and emotional development . When children play together, undirected by a grown-up, they share ideas, listen to one another, and learn to negotiate and reach compromises. This makes social play (like what you’ll find in a playdate) an important part of growing up.

Play also has the following benefits for kids:

- Building self-confidence

- Boosting creativity

- Developing social skills

- Helping memory, language, and symbol recognition

- Teaching stress management

- Promoting healthy physical development

While self-play and play among children is important, it’s also important for you and other loving caregivers to play with your child. It tells them that you’re paying attention to them, and it allows children to express themselves through play. It’s a valuable opportunity to engage fully with your children.[1]

Setting Up and Preparing for a Playdate

You can consider starting with an outside location, like a favorite playground, that’s familiar to both children. This helps them get plenty of fresh air, and gives them lots of space for activities (and you won’t have to tidy up beforehand). Outdoor gatherings are also best at limiting the sharing of airborne germs.[4]

If the weather won’t cooperate, or if your child is nervous about new experiences, you can try hosting the playdate at your house. Your child may feel more comfortable there, and it’s easy for you to monitor the situation.

You’ll likely want to keep the playdate small and short, with only one or two other children, and planned for an hour or two.[3]

One of the most important benefits of a playdate is helping to develop social skills such as sharing. But there might be some times when that’s not an option, say with a special toy. If your child has a prized toy they might not be willing to share, you may want to put it out of sight before the playdate begins.[3]

Learning Lessons From Playing With Other Children

It’s hard to know what goes on inside a child’s head, so it might not always be obvious when children are playing well together or if things are starting to go off course. The Harvard Graduate School of Education has some pointers on how to make sure everyone’s having a good time.

Look for the three indicators of playful learning: choice, wonder, and delight.

- Choice : Children are setting their own goals, sharing ideas, negotiating, and choosing how long to play.

- Wonder : Children can create, explore, and pretend.

- Delight : Children are happy, being silly, and generally at ease.[2]

After the playdate, help your child reflect on how to behave in social situations by pointing out positive behaviors. For instance, you could praise them for letting the other child go first at a game or for when they shared a toy.

You may also take the chance to gently nudge them about social skills they can work on. For instance, if they weren’t great at sharing, you might ask them about it in a kind, non-judgmental way. (“It’s hard to share our favorite toys sometimes, isn’t it?”)[5]

Play is important, and it’s worth doing whatever you can to let your child explore free play time with others and by themselves.

- Ginsburg, Kenneth R. “The Importance of Play in Promoting Healthy Child Development and Maintaining Strong Parent-Child Bonds.” Pediatrics. January 2007. https://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/119/1/182

- Shafer, Leah. “Summertime, Playtime.” Harvard Graduate School of Education. June, 2018. https://www.gse.harvard.edu/news/uk/18/06/summertime-playtime

- EncouragePlay. “Tips for Setting Up Playdates.” September, 2015. https://www.encourageplay.com/blog/tips-for-setting-up-playdates

- Mills, Melissa. “The Post-COVID-19 Playdate Checklist Every Parent Needs.” Parents. July, 2020. https://www.parents.com/health/coronavirus/the-covid-19-pre-playdate-checklist-ever-parent-needs/

- Bright Horizons. “Getting The Most From Play Dates: Teaching Kids About Friendship.” https://www.brighthorizons.com/family-resources/playdates-and-teaching-kids-about-friendship

More Resources articles

Mental Health Awareness Month 2024: 7 Ways to Nurture Your Child’s Mental Health

May is Mental Health Awareness month! For 2021, the theme is “You Are Not Alone,” as chosen by the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI).

12 Children’s Books and Activity Guides to Celebrate Mental Health Awareness Month with Young Learners

May is Mental Health Awareness Month! Stories can mirror a child’s experience to let them know they are not alone and offer them a window

Can You Complete These 48 Summer Reading Challenges?

With all the exciting activities available during the summer, getting kids to read can be a struggle. But if you can find new ways to

Celebrating Juneteenth 2024: Children’s Books and Activities for Families and Educators

MacKenzie Scott’s Yield Giving Awards Waterford.org a $10 Million Grant

Internet Explorer Alert

It appears you are using Internet Explorer as your web browser. Please note, Internet Explorer is no longer up-to-date and can cause problems in how this website functions This site functions best using the latest versions of any of the following browsers: Edge, Firefox, Chrome, Opera, or Safari . You can find the latest versions of these browsers at https://browsehappy.com

- Publications

- HealthyChildren.org

Shopping cart

Order Subtotal

Your cart is empty.

Looks like you haven't added anything to your cart.

- Career Resources

- Philanthropy

- About the AAP

- Supporting the Grieving Child and Family

- Childhood Grief More Complicated Due to Pandemic, Marginalization

- When Your Child Needs to Take Medication at School

- American Academy of Pediatrics Updates Guidance on Medication Administration In School

- News Releases

- Policy Collections

- The State of Children in 2020

- Healthy Children

- Secure Families

- Strong Communities

- A Leading Nation for Youth

- Transition Plan: Advancing Child Health in the Biden-Harris Administration

- Health Care Access & Coverage

- Immigrant Child Health

- Gun Violence Prevention

- Tobacco & E-Cigarettes

- Child Nutrition

- Assault Weapons Bans

- Childhood Immunizations

- E-Cigarette and Tobacco Products

- Children’s Health Care Coverage Fact Sheets

- Opioid Fact Sheets

- Advocacy Training Modules

- Subspecialty Advocacy Report

- AAP Washington Office Internship

- Online Courses

- Live and Virtual Activities

- National Conference and Exhibition

- Prep®- Pediatric Review and Education Programs

- Journals and Publications

- NRP LMS Login

- Patient Care

- Practice Management

- AAP Committees

- AAP Councils

- AAP Sections

- Volunteer Network

- Join a Chapter

- Chapter Websites

- Chapter Executive Directors

- District Map

- Create Account

- Early Relational Health

- Early Childhood Health & Development

- Safe Storage of Firearms

- Promoting Firearm Injury Prevention

- Mental Health Education & Training

- Practice Tools & Resources

- Policies on Mental Health

- Mental Health Resources for Families

Power of Play in Early Childhood

“Play is not just about having fun but about taking risks, experimenting, and testing boundaries.”

Play builds the brain and the body. Play has been shown to support brain structure and functioning, facilitating synapse connection and improving brain plasticity.

Play is also critical to safe, stable, and nurturing relationships, supporting developmental milestones, and mental health.

Depending on the culture to which children grow up, they learn different skills through play.

How does play support child development?

Children learn by exploring their environments and building context from their experiences. Learning thrives when children are given control of their own actions to play.

Play builds motor competence to master fine and gross motor skills, and the confidence to engage in more active play. Motor skill competence lays the foundation for preferences of physical activity. Supporting infants, toddlers, and preschoolers to practice and master their motor skills build their ability.

Play enables social skills such as listening to directions, paying attention, resolving conflict, and negotiating relationships. Play and stress are closely linked. High amounts of play are associated with low levels of cortisol. Play, when supported by nurturing caregivers, may affect brain functions by buffering adversity and reducing toxic stress.

Children learn new words by interacting with others, and repeated exposures to words in various settings. Play supports language development by asking children to decipher meaning and listen and observe cues from others.

Play allows children to practice the language skills they have learned and build on their expanding vocabulary. Interacting with adults and peers also enables children to refine their speech sounds through listening to others.

Play builds skills such as intrinsic motivation and executive functioning. Executive functioning includes working memory, flexible thinking, and self-regulation. Children use these skills to learn, solve problems, follow directions, and pay attention. Play also supports early math skills such as spatial concepts. Executive functioning skills are foundational for school readiness and academic success.

Prescription for Play: Promoting Play in Primary Care

Pediatricians should encourage play at every well child visit especially in the first 2 years of life. Providers can provide strategies for incorporating play in every day interactions. Explore example strategies provided below.

Tummy time! Tummy time helps build your baby’s neck and shoulder muscles to support sitting, crawling, and eventually walking. Babies benefit from 2 to 3 tummy time sessions each day for a short period of time (3 to 5 minutes). As your baby grows they will enjoy longer sessions.

Don’t forget to play with your child. Get on the floor eye to eye with your baby. Make faces, wiggle your fingers, slowly move a colorful object in front of your baby’s eyes from about 10–12 inches away.

- Offer your baby safe objects to mouth. Watch as he gazes at the object that interests him, reaches for it, and then mouths it to figure out what it is!

- Sing, chat, tickle, count toes

- Make faces, smile, laugh, roll your eyes or poke out your tongue.

- Offer different objects to feel – soft toys, rattles or cloth books with pages of different textures are lots of fun to explore.

- Read to your baby. Don’t be afraid to have fun too! Use silly voices, point out pictures and colors.

- Let your child choose what to play. Talk about what you and your child are doing during play. Repeat words or phrases many times to help your child learn new words.

- Turn everyday activities into opportunities for play. Play make believe while cleaning the house; take turns making a story while running errands, sort foods into colors or shapes while shopping.

- Chunky puzzles

- Memory-type games

- Stacking cups or ring stacks

- Shape-sorters and bead mazes

- Make your own Memory game using photos of family members or favorite places.

Preschoolers

- Make-believe play such as dress-up, dressing and feeding a doll- let your child lead the story

- Your child enjoys sorting objects into groups or creating simple crafts. Allow them to sort everyday objects such as kitchen utensils, cardboard boxes, shoes, etc.

- Simple board games

- Make a game out of dressing- ask your preschooler to name their body parts

Supporting Families

Parents may feel they need expensive toys and experiences for their child. However, children’s creativity and play is enhanced by their experiences with caregivers and their friends. Many inexpensive toys such as balls, puzzles, crayons, and simple household objects are great options for play.

Message to families: Your child loves playing with you. You can find simple items such as crayons, paper, empty cardboard boxes, balls, and others things to play with together.

Families may also struggle finding time to play in between long work hours. Play can be anywhere and for small amounts of time. The quality of time and level of play is most important.

Message to families: Playful moments are everywhere! Make believe while running errands, sort foods at the grocery store, turn cleaning into a game.

Many children do not have safe places to play. Parents wisely choose their child’s safety over outdoor play opportunities.

Message to families: It can be hard to find safe places for your family to play. Lets think of ways to play in your home or find safe places in your community.

Last Updated

American Academy of Pediatrics

- Why We Play

- Attunement Play

- Movement Play

- Play Personalities

- In Pre-K and Kindergarten

- What Is Your Play Nature

- Prescribe Free Play

- Scientific Disciplines Researching Play

- What We Know So Far

- Play Scientists and Experts

- Library Overview

- Research Articles

- Other Play Resources

- Our Founder

- Our History

- Board of Directors

- Our Sponsors

The Value of Play

Most recognize that play is good for children yet we are confused by the dangers we see in the wider environment and so often restrict children’s natural opportunities to play. As a result children’s play has gained increased awareness amongst a variety of professions working with children, many of whom have different approaches to play and children. The Value of Play is explained using the Integral Play Framework, a model that draws together differing views on the purpose of play and its various types. These ideas are then used as the basis for chapters of the book: showing why playing is valuable to our bodies, our minds, and culturally and socially. There are examples of how play can be supported both informally and formally, at home and in children’s settings. As well as theory, there are relevant, practical approaches for play activities, and observations of playing children to help explain the processes. Key questions are asked at times to help those who may be engaged in a more reflective form of practice. The Value of Play has been written to be accessible by a broad spectrum of readers, including all those training to work with children; those specifically engaged in playwork as a field in itself; and those on Childhood Studies programmes.

Outdoor Play Canada

Privacy overview.

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-advertisement | 1 year | Set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin, this cookie is used to record the user consent for the cookies in the "Advertising" category. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-advertising | 1 year | This cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Advertising". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other." |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| CookieLawInfoConsent | 1 year | Records the default button state of the corresponding category & the status of CCPA. It works only in coordination with the primary cookie. |

| PHPSESSID | session | This cookie is native to PHP applications. The cookie is used to store and identify a users' unique session ID for the purpose of managing user session on the website. The cookie is a session cookies and is deleted when all the browser windows are closed. |

| ts | 3 years | PayPal sets this cookie to enable secure transactions through PayPal. |

| ts_c | 3 years | PayPal sets this cookie to make safe payments through PayPal. |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| _ga | 2 years | The _ga cookie, installed by Google Analytics, calculates visitor, session and campaign data and also keeps track of site usage for the site's analytics report. The cookie stores information anonymously and assigns a randomly generated number to recognize unique visitors. |

| _ga_QG5Y14178J | 2 years | This cookie is installed by Google Analytics. |

| _gat_gtag_UA_159087048_1 | 1 minute | Set by Google to distinguish users. |