Contact: ✉️ [email protected] ☎️ (803) 302-3545

What is an inaugural address.

Presidents of the United States deliver a plethora of speeches during their time in office. One of the most important of them all is the inaugural address. What is an inaugural address? What is the intention of the speech, why is it so significant, and how can the President be sure to get it right?

What is an inaugural address?

The inaugural address is the speech delivered by the President following their Oath of Office. It is a chance to speak directly to the nation and provide a clear message about the four years ahead. When well-crafted and delivered effectively, it can give the President a positive start to their first term .

Delivering an Address During an Inauguration

The inaugural address is a massive moment in the long inauguration process. There is a grand ceremony on the western front of the United States Capitol where the President and Vice President are sworn into office to begin the new term. After the oath at noon, the new President delivers their speech to the nation.

The position of the ceremony allows the President to speak to hundreds of guests in attendance, but also thousands lining the National Mall and the millions watching on TV worldwide. It is no surprise that there is a lot of pressure to get the speech just right.

Everything from the structure and length of the speech to the tone and eloquence of the delivery falls under a microscope. People will judge the new President based on these words, especially those that voted for the other guy. So, each speech must be bipartisan, inspiring, perfectly composed, and just the right length.

The Length of an Inaugural Address

There is no specific length for an inaugural address. Presidents can make theirs as long or as short as they want. Some choose the former to make the most of their time and say all they need to say, while others keep it short and sweet.

Get Smarter on US News, History, and the Constitution

Join the thousands of fellow patriots who rely on our 5-minute newsletter to stay informed on the key events and trends that shaped our nation's past and continue to shape its present.

Check your inbox or spam folder to confirm your subscription.

President George Washington’s second inaugural address was a good example of keeping things short. As the only person to hold office, there was no precedent in place or any expectation for a long speech and drawn-out speech. So, he said just 135 words, repeated the oath, and returned to work.

Over the decades, the speech has become a more symbolic moment in the ceremony, with greater expectations over the message and length. When Washington’s Vice President , John Adams, won his election, he delivered a speech of 2308 words – including one 737-word sentence. The longest ever came from William Henry Harrison , with an 8,445-word address in the pouring rain.

Quality Over Quantity Helps With a Good Inaugural Address

The length of a speech is nowhere near as important as the message within. We will probably forget how long we spent waiting for a speech to end but will share quotes and videos from a good speech for a long time. So, each new President has to ensure that they set out their goals and principles in an appropriately presidential manner without going too far.

Franklin D Roosevelt was a good example of one who knew when to keep things short and to the point. His fourth address did not overstay its welcome at just 559 words. By this point, the nation knew the man and his ideals as he had been elected to a historic fourth term. On top of that, Roosevelt was keen to keep things simple with a basic ceremony at the White House due to America’s involvement in World War II.

Creating a Strong Bipartisan Address

An inauguration marks a new chapter in the nation’s history, so it makes sense for the President to highlight this after taking the oath. Some will reflect on the chance to make improvements for the nation or to lead them out of times of trouble. Others will reaffirm their desire to continue their hard work and dedication for a second term.

Ideally, these speeches should be bipartisan. This isn’t a time to talk down to the opposition in victory or to talk about all the ways a previous administration failed the nation. Doing so runs the risk of causing a divide in the crowds of people watching – either at the National Mall or on TV.

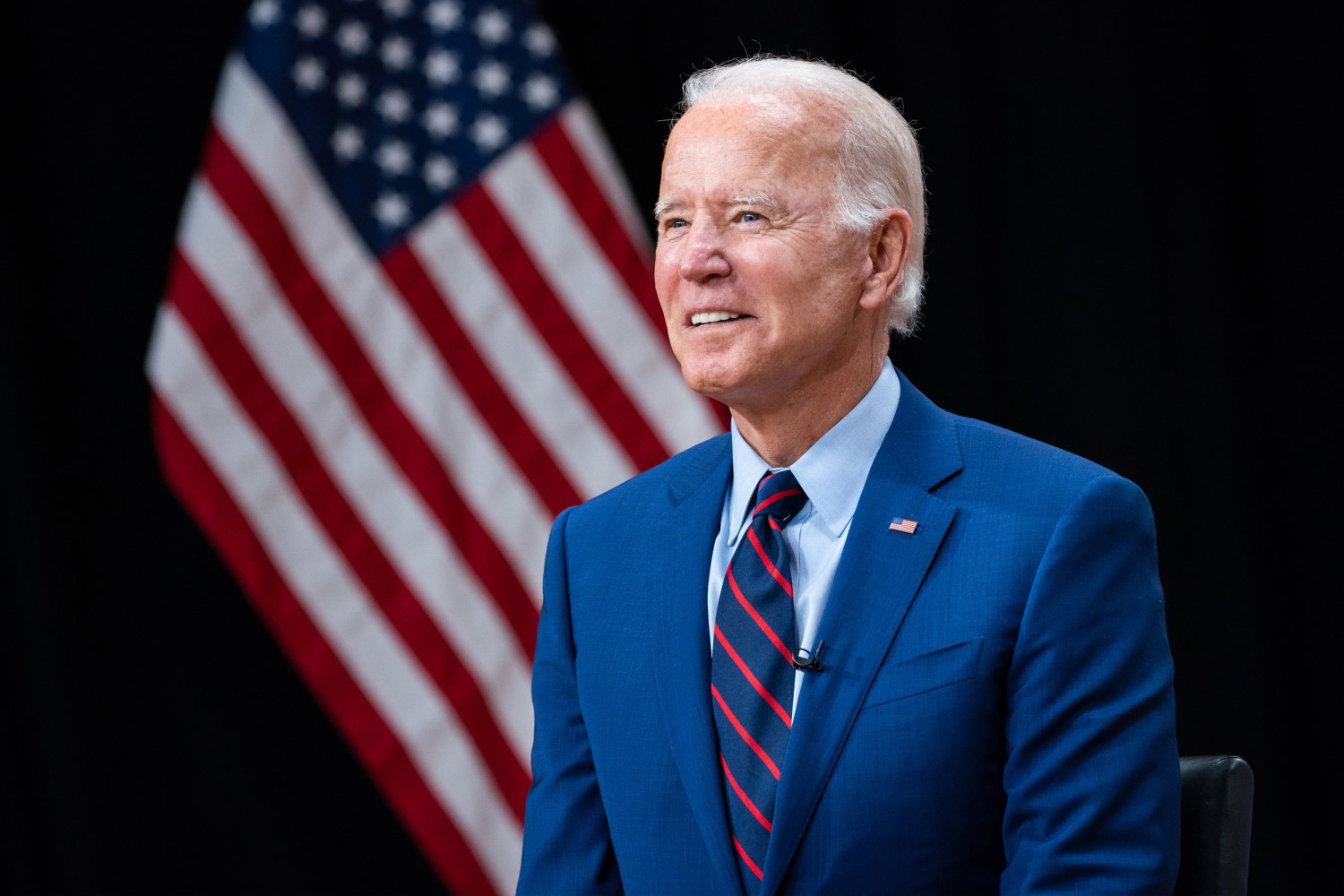

President Joe Biden’s 2021 address is a good example of this with its opening lines. “This is America’s day. This is democracy’s day. A day of history and hope. Of renewal and resolve.” This speech set a strong positive tone, whereas his predecessor, Donald Trump’s speech, was criticized for its bleak and dystopian outlook.

Who Writes the Presidential Inaugural Address?

You might assume that the President is the one to write the speech if it is such an important moment for them to articulate their vision and goals. However, the scale of the occasion and scrutiny of the speech means that this isn’t always the case. In the past, the first presidents undoubtedly did spend hours penning their own speeches, but not today.

The idea of the political speech writer is not such a big deal these days. We know that the White House has a communications team to create important speeches – often with multiple versions depending on a desired tone or outcome. They have been in use since the days of Calvin Coolidge .

Therefore, it makes sense that this grand public address is another writer’s work. They are typically skilled and trusted members of the President’s team who can take the ideas and references given by the President and spin them into gold.

The Inaugural Address Will Always Be an Important Moment in the Presidency

There will always be debate over who created the best or worst inaugural addresses in history. Often, the oratory skills of the man elevate the words into something even more profound. What is clear is that these speeches have great power, and each President must get it just right. Otherwise, the inauguration day address will go into the history books for all the wrong reasons.

Alicia Reynolds

Presidents who declared a national emergency, what is the order of succession for presidency, presidents that encouraged the united states to practice isolationism, which presidents were assassinated, please enter your email address to be updated of new content:.

© 2023 US Constitution All rights reserved

Words Matter: What an Inaugural Address Means Now

Jan 15, 2021, 6:35 AM

UNIFYING THEME: Polarization: Its Past, Present and Future

Presidents' words create national identity. For better or worse, presidential rhetoric tells the American people who they are. Ultimately, a president's voice must provide the American people with a concrete vision of how-and more importantly, why-to move forward together.

RELATED NEWS featuring Vanessa Beasley:

- U.S. News & World Report: "Limited Power for the World's Most Powerful Man" (July 16, 2021)

By Vanessa B. Beasley , Associate Professor of Communication Studies and Vice Provost for Academic Affairs

Presidents' words matter. Such a statement may seem especially relevant right now, but it has been true throughout the course of U.S. history. Richard Neustadt wrote in 1960 that "presidential power is the power to persuade," and much of his focus was on how chief executives must bargain with members from other branches of government. Yet consider how much of presidents' executive action can be done through their words alone as well as how far those words can now reach due to the rise of mass and social media. They can veto, nominate, declare war, agree to peace, issue executive orders, define the state of the union, and pardon. Today, as Karlyn Kohrs Campbell and Kathleen Hall Jamieson have argued, "[P]residential rhetoric is the source of executive power, enhanced in the modern presidency by the ability to speak where, when, and on whatever topic they choose and to reach a national audience through coverage by the electronic media."

In the aftermath of the 2020 presidential election, many are thinking about the difference between what a president's words can do and what they should do. Recent images of the Capitol steps captured this contrast clearly when insurrectionists, determined to break into the building and terrorize its occupants, transformed the scaffolding installed for the ceremony of a peaceful transfer of power on Inauguration Day into scaling ladders. In the days since, amidst heightened fears for public safety, there have been recurring questions about what kinds of security will be required on Inauguration Day 2021. But what kinds of words could possibly be deployed as well?

When we consider the history of what most presidents have said when inaugurated, it is worth remembering this is an invented tradition; there is no Constitutional requirement for a new president to give an inaugural address. The actual requirement is only for the new president to be sworn in and take an oath per Article II, Section 1. Yet ever since George Washington chose to give an inaugural address in April 1789, in New York City, his successors have given such a speech. In addition to becoming a traditional part of a larger civic ritual, over time this speech has come to occupy a unique space in the public performance of the presidency.

Listening to-and later, watching-an inaugural address can inform both U.S. citizens and the broader world alike what kind of leader a new president will be. Think of a young John F. Kennedy, inexperienced in foreign policy, giving his inaugural address at the height of the Cold War, with outgoing president (and architect of D-Day) Dwight Eisenhower nearby in camera shot from almost every angle. Today Kennedy's inaugural address may be remembered for its elegant, moving chiasmus-"Ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country"-focused on domestic service. On the day it was given, though, the visual message designed for a global television audience in general and the Soviet Union in particular was meant to be just as noticeable: The United States might have a new president, but it was no less prepared to protect democracy around the world.

As this example indicates, a presidential inaugural address is arguably less about an individual president and more about how well and fully he (and one day soon, she) comprehends this new role and its symbolic import. This speech offers the first public test. Does the new office holder truly know how to act on the oath just taken, acknowledging the necessity to transcend the views of one person or one party? In other words, this speech signals how much the new president understands what the presidency means-or can mean-to the American people, whose communal shared interests the U.S. president, as opposed to members of Congress shivering behind him, has vowed to safeguard. For this reason, the inaugural address needs to be grounded in historical tradition but also responsive to the emergent needs of its own time.

Arguably, few presidents have understood this need better than Washington did. In his inaugural address, he referred to the speech itself as his "first official act" as president, a role many of his contemporaries were dubious about due to fears the position would simply replicate the British monarchy or otherwise steer too much power into a nascent federal system. Within this context, Washington crafted the very first presidential words ever uttered for the purpose of reassuring his audience, those in attendance in the Senate Chamber as well as those who would read about the speech in the following days. His intentions were clear. He would remain humble and serve despite his own "anxieties," a word he used in the first sentence; remain reverent to the "Almighty Being who rules over the universe" and who might presumably favor the new nation; and, more than anything else, remain obliged to the new Congress (acknowledging he understood the Constitutional limitations imposed on the executive) and therefore the "public good."

To define this wholly new concept of an American public good, Washington did not spell out a policy agenda but identified what his role as its guardian would require: "no local prejudices, or attachments; no separate views, nor party animosities, will misdirect the comprehensive and equal eye which ought to watch over this great assemblage of communities and interests…." With Federalists and Anti-Federalists having been at odds about the structure and scope of the new government, Washington was not only carving out clear ground for the presidency, but he was also providing ideological rivals with an alternative way to view themselves. They might remain political adversaries, but they should always remember that they were the custodians of an "experiment entrusted to the hands of the American people," who must surely remain focused on "a regard for the public harmony."

It would be up to Washington's successors to similarly define and eventually expand American national identity in such transcendent terms. As I have argued elsewhere, the great majority of presidents have done so with remarkable similarity, using themes related to civil religion to define American identity as overriding other partisan or sectional allegiances. Historically, civil religious themes have been associated with American national identity not only because of their pseudo-religious aspects (e.g., a promise of providential favor on the United States, as in Washington's inaugural, or the subsequent political appropriation of John Winthrop's scriptural framing of the land as "a shining city on a hill") but also because of the idea that the nation offered its citizens opportunities to become someone new, a recurring theme of American identity also famously captured by early foreign observers such as Crevecoeur and de Tocqueville.

This idea of the inaugural address as an invitation to collective renewal--of convening a new beginning, together--is also one of the patterns identified by Campbell and Jamieson in their study of the characteristic rhetorical elements consistent in all presidential inaugurals over time. Especially after contentious elections, they write, this first speech must respond to an urgent need to "unif[y] the audience by reconstituting its members as 'the people,' who can witness and ratify the ceremony." Viewed through this lens, the address is therefore not only an opportunity for presidents to demonstrate an understanding of their role, but it is also an opportunity for "the people" to do the same.

An example is Thomas Jefferson's first inaugural after the fiercely divisive election of 1800, which was also the first time an incumbent president had not been reelected. To reunite a divided people, Jefferson did not ignore the reality of the divisions still among them or the unprecedented nastiness of the campaign. "During the contest of opinion through which we have passed, the animation of discussion and of exertion has sometimes worn an aspect which might impose on strangers unused to think freely and to speak and to write what they think," he noted, reminding citizens that it was their unique democratic privilege to be able to disagree so openly about politics. "But this now being decided by the voice of the nation, announced according to the rules of the Constitution, all will, of course, arrange themselves under the will of the law, and unite in common efforts for the common good." Jefferson was defining American identity by setting a clear boundary: Americans follow the rules, even when they do not like the outcome.

And yet of course any discussion of Jefferson's definition of American character must state the obvious: Like Washington, he was never really speaking to or about all of the inhabitants of the United States. There was no acknowledgement of enslaved people or indigenous people as part of this common good. There was no sense that these people were part of what was being reunited after an election or at any other time either. Following the rules of the day, in fact, demanded otherwise, including the violent separation of kin and tribe in order to build a new nation. Likewise, while white women were considered invaluable to a virtuous republic, there was no understanding that their interests might be in any way different from the white men who voted presumably, if not always accurately, for them.

In 2021, an awareness of how many of "the people" have been ignored in prior inaugural addresses raises questions about what an inaugural address means now. If it is to be rooted in rhetorical traditions, which ones? Like other genres of presidential speech, inaugural addresses are constructed around pillars of baked-in impulses and assumptions held by previous generations about who deserved to be called an American and whose interests should be included in a non-partisan, unifying sense of the common good. Even one of the most beautiful phrases in any inaugural, Lincoln's appeal to the "better angels of our nature" in his first, gives pause when you realize that the "us" implied in Lincoln's sense of "our nature," was necessarily almost exclusively white and male because of who his intended audience in 1861 was as well as his stated intent in the same speech not to interfere with "the institution of slavery" during his presidency.

Does this fact mean that Lincoln's first words as president, like the traditions they were written to follow, are irrelevant to what presidents should do today when they invite the American people to renew their faith in a democratic republic? To the contrary, they are instructive exactly because they reveal where to begin the rhetorical work that remains to be done: the revision of a tradition of presidential speech with the explicit goal of expanding the common good into something larger than partisan interest or individual gain, as the previous examples indicate, but also making it clear in unequivocal terms that everyone has a stake in this good. Everyone.

At this moment, it may be difficult to imagine what that would sound like. Barack Obama's notion of the nation as an imperfect but evolving union comes to mind as one possible foundational trope, even though it originally came from one of his campaign speeches and not the bully pulpit. It may also be true that, over time, the televised spectacle of the inauguration itself-coverage of the formal breakfast, the fancy dress balls, and even the breathiness of the news announcers pointing out who is and is not attending this time-has increasingly turned our collective attention to the ceremony as primarily a visual event rather an oratorical one. If this is true, it could explain why Donald Trump clung so tightly to his claims about how many attendees packed onto the Capitol lawn and parade route in January, 2017. Perhaps his belief was that such imagery alone was sufficient to represent a nation united in its hopes for a new president.

Images are rhetorical, to be sure. I began this essay by referencing the horrific images of the U.S. Capitol on the afternoon of January 6, 2021. As haunting as those photographs and videos are, and as much as even a rhetorician like myself must concede that words cannot repair everything, words are almost always the place to start looking for both cause and effect. Now is the moment to take seriously what presidents' words can do.

A president's words on Inauguration Day reveal not only what kind of president he or she will be, but they also should offer an idiom of identity the American people might imagine they can share. In 2021, as it was in another speech given by Abraham Lincoln in 1863, it may be time to think carefully about how words may have the potential to remake America. At minimum, we must consider more expansively and honestly than ever before who "we" are, who "we" have been, and how "we" can move forward if the nation is to be renewed. Does the peaceful transition of power from one U.S. president to another require that a new chief executive give an inaugural address as part of a civic ritual of renewal? No. Does the prospect of authentic unity among the American people depend on the invocation of an expansive "us" able to imagine a common good not yet realized? Yes.

- Vanessa Beasley

Vanessa Beasley , a Vanderbilt University alumna and expert on the history of U.S. political rhetoric, is vice provost for academic affairs, dean of residential faculty and an associate professor of communication studies. As Vice Provost and Dean of Residential Faculty, she oversees Vanderbilt's growing Residential College System as well as the campus units that offer experiential learning inside and outside of the classroom.

Following stints on the faculty of Texas A&M University, Southern Methodist University and the University of Georgia, she returned to Vanderbilt in 2007 as a faculty member in the Department of Communication Studies . Active in the Vanderbilt community, she has served as chair of the Provost's Task Force on Sexual Assault, director of the Program for Career Development for faculty in the College of Arts and Science, and as a Jacque Voegeli Fellow of the Robert Penn Warren Center for the Humanities.

Beasley's areas of academic expertise include the rhetoric of American presidents, political rhetoric on immigration, and media and politics. She is the author of numerous scholarly articles, book chapters and other publications, and is the author of two books, Who Belongs in America? Presidents, Rhetoric , and Immigration and You, the People: American National Identity in Presidential Rhetoric, 1885-2000. She was recently named president-elect of the Rhetoric Society of America , set to begin her term in July 2022.

Beasley attended Vanderbilt as an undergraduate and earned a bachelor of arts in speech communication and theatre arts. She also holds a Ph.D. in speech communication from the University of Texas at Austin.

[1] Richard Neustadt, Presidential Power and the Politics of Leadership (New York: John Wiley and Sons, 1960), 11.

[2] Karlyn Kohrs Campbell and Kathleen Hall Jamieson, Presidents Creating the Presidency: Deeds Done in Words , 2 nd ed (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008), 6.

[3] Authenticated text available at https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/inaugural-address-2.

[4] Authenticated text available at https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/people/president/george-washington

[5] Authenticated text available at https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/people/president/george-washington

[6] Authenticated text available at https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/people/president/george-washington

[7] Vanessa B. Beasley, You, The People: American National Identity in Presidential Rhetoric (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2004).

[8] Karlyn Kohrs Campbell and Kathleen Hall Jamieson, Presidents Creating the Presidency: Deeds Done in Words , 2 nd ed (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008).

[9] Campbell and Jamieson, Presidents Creating the Presidency , 31.

[10] Authenticated text available at https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/inaugural-address-19

[11] Beasley, You, the People.

[12] Authenticated text available at https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/inaugural-address-34

[13] Authenticated text and audio available at https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=88478467

[14] Gary Wills, Lincoln at Gettysburg: The Words that Remade America (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1992).

Explore Story Topics

- Polarization

- Polarization: Its Past Present and Future

All Subjects

Advanced Public Speaking

Study guides for every class, that actually explain what's on your next test, inaugural address, from class:.

An inaugural address is a ceremonial speech given by an incoming president or leader at the beginning of their term in office. This speech typically sets the tone for the new administration, outlines key priorities, and seeks to unify and inspire the public. Inaugural addresses are significant not only for their content but also for their historical context and the way they reflect the values and aspirations of the time.

congrats on reading the definition of inaugural address . now let's actually learn it.

5 Must Know Facts For Your Next Test

- Inaugural addresses are traditionally given during a public ceremony following the inauguration of a president, typically held in front of the Capitol building in Washington, D.C.

- The first inaugural address was delivered by George Washington in 1789, establishing a precedent for future presidents to follow.

- Inaugural addresses often contain themes of hope, change, and unity, aiming to bring together diverse groups within the nation after an election.

- The use of rhetorical devices such as parallelism, alliteration, and metaphors is common in inaugural addresses to enhance their emotional impact.

- Some inaugural addresses have become iconic due to their powerful messages or memorable phrases, influencing public sentiment and historical narratives.

Review Questions

- Inaugural addresses frequently use rhetorical strategies like repetition, metaphors, and parallelism to emphasize key themes and connect emotionally with the audience. These strategies help create a rhythm that captures attention while also underscoring important ideas such as unity and resilience. By effectively employing these techniques, speakers aim to inspire hope and mobilize public support for their administration’s goals.

- Inaugural addresses have evolved significantly alongside shifts in political ideologies throughout U.S. history. Early addresses focused primarily on establishing authority and addressing foundational principles. As societal values changed, more recent speeches have included broader themes such as social justice, economic equality, and international relations. This evolution reflects not only the personal beliefs of the presidents delivering them but also the changing expectations and concerns of the American public.

- Memorable inaugural addresses can significantly impact American political culture by shaping public perceptions of leadership and governance. Iconic speeches often resonate with citizens long after they are delivered, influencing national dialogue and inspiring civic engagement. For example, phrases from famous addresses may become rallying cries for movements or set expectations for governmental action, thus encouraging citizens to become more actively involved in political processes and community initiatives.

Related terms

Rhetoric : The art of persuasive speaking or writing, often used in political contexts to influence an audience's beliefs and actions.

Political Ideology : A set of beliefs about the proper order of society and how government should operate, which can heavily influence the content of political speeches.

Unity : The state of being united or joined as a whole, often emphasized in inaugural addresses to promote collective national identity and purpose.

" Inaugural address " also found in:

Subjects ( 5 ).

- American Presidency

- Honors US History

- Intro to American Government

- Intro to Political Communications

© 2024 Fiveable Inc. All rights reserved.

Ap® and sat® are trademarks registered by the college board, which is not affiliated with, and does not endorse this website..

Inauguration History

A Smithsonian magazine special report

Behind Inaugural Speeches, Meaningful Words

What words do presidents focus on most in their inaugural addresses? Explore speeches, from Washington to Obama

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Inaugural-Speeches-Meaningful-Words-631.jpg)

George Washington's First Inaugural Address

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/George-Washington-inauguration-text.jpg)

George Washington delivered his first inaugural address before a joint session of Congress in New York City’s Federal Hall on April 30, 1789. Washington, stepping into the newly created role of president, spoke of the importance of government’s duty to the public. He was deferential to his fellow patriots, almost hesitant to take on the role of the leader of the nation: “I shall again give way to my entire confidence in your discernment and pursuit of the public good.” Read the full speech at: Bartelby.org

Abraham Lincoln's First Inaugural Address

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Abraham-Lincoln-first-inauguration-text.jpg)

By the time Abraham Lincoln delivered his first inaugural address on March 4, 1861, seven Southern states had seceded from the Union to form the Confederate States of America. In his speech, relying on frequent references to the Constitution, Lincoln argued that the Union was indissoluble: “Plainly the central idea of secession is the essence of anarchy. A majority held in restraint by constitutional checks and limitations, and always changing easily with deliberate changes of popular opinions and sentiments, is the only true sovereign of a free people.” Read the full speech at: Bartelby.org

Abraham Lincoln's Second Inaugural Address

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Abraham-Lincoln-second-inauguration-text.jpg)

With the Civil War coming to an end, Lincoln’s Second Inaugural emphasized the need for national reconciliation to continue the task of preserving the Union: “With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in, to bind up the nation’s wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow and his orphan, to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations.” Historian and Lincoln biographer Ronald C. White Jr. deemed the Second Inaugural Lincoln’s greatest speech, describing it as a “culmination of Lincoln’s own struggle over the meaning of America, the meaning of the war, and his own struggle with slavery.” Read the full speech at: Bartelby.org

Theodore Roosevelt's Inaugural Address

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Theodore-Roosevelt-inauguration-text.jpg)

Theodore Roosevelt took his first oath of office following the assassination of President William McKinley in 1901. In 1904, Roosevelt was elected to the White House, winning 56 percent of the popular vote. His inauguration was a festive affair, with a contingent of Rough Riders joining in the procession. But the tone of Roosevelt’s inaugural speech was somber, as he used the occasion to call attention to the unprecedented challenges facing the United States during an era of rapid industrialization: “[The] growth in wealth, in population, and in power as this nation has seen during the century and a quarter of its national life is inevitably accompanied by a like growth in the problems which are ever before every nation that rises to greatness.” Read the full speech at: Bartelby.org

Woodrow Wilson's Second Inaugural Address

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Woodrow-Wilson-second-inauguration-text.jpg)

President Woodrow Wilson had campaigned for re-election on the slogan “He kept us out of war.” But by the time he delivered his second inaugural address on March 5, 1917, war with Germany seemed inevitable. In his speech, Wilson declared: “The tragic events of the thirty months of vital turmoil through which we have just passed have made us citizens of the world. There can be no turning back. Our own fortunes as a nation are involved whether we would have it so or not.” Wilson also enunciated a list of principles—such as freedom of navigation on the seas and the reduction of national armaments—that foreshadowed the “Fourteen Points” speech he would deliver to a joint session of Congress on January 8, 1918. Read the full speech at: Bartelby.org

Franklin Delano Roosevelt's Second Inaugural Address

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Franklin-Delano-Roosevelt-second-inauguration-text.jpg)

Buoyed by a decisive re-election victory—including strong gains by the Democratic Party in Congress—Roosevelt laid out his continuing plans to bring America out of the Great Depression. “I see one-third of a nation ill-housed, ill-clad, ill-nourished,” the president said. But Roosevelt counseled hope instead of despair, arguing that government has the “innate capacity to protect its people” and “to solve problems once considered unsolvable.” Read the full speech at: Bartelby.org

Franklin Delano Roosevelt's Third Inaugural Address

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Franklin-Delano-Roosevelt-third-inauguration-text.jpg)

With Europe and Asia already engulfed in war, Roosevelt’s Third Inaugural warned Americans about the “peril of inaction.” He spoke in broad terms about nations and spirit, and perceptively compared the threats confronting the United States to those facing Washington and Lincoln in generations past. “Democracy is not dying,” he declared. “We know it because we have seen it revive—and grow.” Read the full speech at: Bartelby.org

Franklin Delano Roosevelt's Fourth Inaugural Address

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Franklin-Delano-Roosevelt-fourth-inaguration-text.jpg)

President Franklin Delano Roosevelt delivered his fourth and final inaugural address in 1945. With the nation still at war, it was considered inappropriate to mark the occasion with festivities—and his speech, less than 600 words long, echoed the day’s solemn tone. Much of the address focused on the perils of isolationism: “We have learned that we cannot live alone, at peace; that our own well-being is dependent on the well-being of other nations far away. We have learned that we must live as men, not as ostriches, nor as dogs in the manger.” Read the full speech at: Bartelby.org

Harry S. Truman's Inaugural Address

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Harry-S-Truman-inauguration-text.jpg)

When President Harry S. Truman delivered his inaugural address on January 20, 1949, the cold war was well underway: The Iron Curtain had fallen over Eastern Europe, the Soviet Union had attempted to blockade West Berlin and the United States had begun implementing its policy of “containment” by providing financial and military aid to Greece and Turkey. In his speech, Truman outlined an ambitious “program for peace and freedom,” emphasizing four courses of action: strengthening the effectiveness of the United Nations; promoting world economic recovery; strengthening freedom-loving nations against the dangers of aggression; and launching an initiative “for making the benefits of our scientific advances and industrial progress available for the improvement and growth of underdeveloped areas.” Read the full speech at: Bartelby.org

John F. Kennedy's Inaugural Address

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/John-F-Kennedy-inauguration-text.jpg)

John F. Kennedy’s inaugural speech is perhaps best known for its use of the coupling, “My fellow Americans, ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country.” But, during an era of rising cold war tensions, Kennedy also addressed an international audience: “Let every nation know, whether it wishes us well or ill, that we shall pay any price, bear any burden, meet any hardship, support any friend, oppose any foe, in order to assure the survival and the success of liberty.” Like other presidents before and since, Kennedy expressed optimism about the ability of the current generation of Americans to confront the unique burdens that had been placed upon them. Read the full speech at: Bartelby.org

Ronald Reagan's First Inaugural Address

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Ronald-Reagan-first-inauguration-text.jpg)

The cornerstone of Ronald Reagan’s economic and legislative philosophy is well summarized by his assertion that “In our present time, government is not the solution to our problem, government is the problem.” (Compare the prominence of the word “government” in Reagan’s First Inaugural and Roosevelt’s Second, and you’ll see how the two transformational icons viewed their role as president.) On the day of the inauguration, the U.S. hostages in Iran were released after 444 days in captivity. Reagan referenced the crisis in saying, “As for the enemies of freedom, those who are potential adversaries, they will be reminded that peace is the highest aspiration of the American people.” Read the full speech at: Bartelby.org

Ronald Reagan's Second Inaugural Address

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Ronald-Reagan-second-inauguration-text.jpg)

On a frigid winter day—so cold that the ceremony took place in the Capitol Rotunda instead of on the Capitol’s west steps—Ronald Reagan spoke of restricting the scope of federal government, pledging to keep Americans safe from undue “economic barriers” and to “liberate the spirit of enterprise” for all. The president also addressed national security, emphasizing the responsibility of the United States to promote democracy abroad. Reagan denounced the immorality of nuclear weapons and mutual assured destruction, and used his address to further his case for a missile defense shield. Read the full speech at: Bartelby.org

Bill Clinton's First Inaugural Address

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Bill-Clinton-first-inauguration-text.jpg)

Bill Clinton defeated incumbent President George H.W. Bush in 1992, when the country was in the midst of an economic recession. Yet his speech largely focused on America’s place in the world during an era of unprecedented economic and political globalization: “There is no longer division between what is foreign and what is domestic—the world economy, the world environment, the world AIDS crisis, the world arms race—they affect us all.” Read the full speech at: Bartelby.org

Bill Clinton's Second Inaugural Address

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Bill-Clinton-second-inauguration-text.jpg)

During his campaign for re-election in 1996, President Clinton promoted the theme of building a bridge to the 21st century. His second inaugural speech touched upon the same theme, and Clinton spoke optimistically about setting “our sights upon a land of new promise.” In a twist on President Reagan’s famous line from his first inaugural, Clinton said: “Government is not the problem, and government is not the solution. We—the American people—we are the solution.” Read the full speech at: Bartelby.org

George W. Bush's First Inaugural Address

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/George-W-Bush-first-inaguration-text.jpg)

Following years of political scandals and bitter fighting between President Bill Clinton and the Republican-controlled Congress, many pundits praised President George W. Bush’s first inaugural speech for its themes of compassion, service, character—and especially the promise to bring civility to politics. Newsweek’s Evan Thomas wrote: “Bush studied John F. Kennedy’s brief Inaugural Address before preparing his own. Bush’s themes of courage and service echoed JFK’s—without the heavy overhang of the ‘long twilight struggle’ of the cold war, but with the same emphasis on duty and commitment, words Bush repeated several times.” Read the full speech at: Bartelby.org

George W. Bush's Second Inaugural Address

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/George-W-Bush-second-inauguration-text.jpg)

President George W. Bush’s second inaugural address was delivered in the aftermath of the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks and the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq. Seeking to place his foreign policy in a broad, historical context, Bush declared: “The survival of liberty in our land increasingly depends on the success of liberty in other lands. The best hope for peace in our world is the expansion of freedom in all the world.” Bush had told his chief speechwriter, Michael Gerson, “I want this to be the freedom speech.” Gerson didn’t disappoint: during the course of the 21-minute address, Bush used the words “freedom,” “free” and “liberty” 49 times. Read the full speech at: Bartelby.org

Barack Obama's First Inaugural Address

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Barack-Obama-Inagural-Speech-text.jpg)

Barack Obama's inaugural address cited the historic change his presidency represents and candidly recognized the many challenges facing the nation in his term ahead, from war abroad to economic turmoil at home. "The challenges we face are real. They are serious, and they are many. They will not be met easily or in a short span of time," he declared. "But know this, America—they will be met." He promised "bold and swift action" to restore the economy. "Starting today, we must pick ourselves up, dust ourselves off, and begin again the work of remaking America." Read the full speech at: Bartelby.org

Barack Obama's Second Inaugural Address

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/barack-obama-second-inaugural-address.jpg)

Barack Obama’s second inaugural address reiterated his campaign theme of fairness, explaining that a nation can’t succeed "when a shrinking few do very well and a growing many barely make it.” Starting many statements with “we, the people,” Obama called on citizens to work together to achieve an agenda that was lauded by liberals but criticized by conservatives. He became the first president to reference protecting gay rights in an inaugural address, and highlighted climate change, declaring, “Some may still deny the overwhelming judgment of science, but none can avoid the devastating impact of raging fires and crippling drought and more powerful storms.”(Written by Marina Koren) Read the full speech at: Bartelby.com

Get the latest History stories in your inbox?

Click to visit our Privacy Statement .

Presidential Inaugural Addresses

Published: January 22, 2021

"Before he enter on the Execution of his Office, he shall take the following Oath or Affirmation:—“I do solemnly swear (or affirm) that I will faithfully execute the Office of President of the United States, and will to the best of my Ability, preserve, protect and defend the Constitution of the United States." The Constitution of the United States, Article II, Section I

In addition to the Constitutionally-mandated Oath of Office, Presidents since George Washington have customarily given inaugural addresses upon assuming office. On GovInfo, these addresses are included within the daily and bound versions of the Congressional Record. Until 1937, Presidential Inaugurations were held on March 4th. The date was changed to January 20th as part of the 20th Amendment .

For Presidents prior to Ulysses S. Grant, see the Joint Congressional Committee on Inaugural Ceremonies' Inaugurations site .

Inaugural Addresses

Joseph r. biden jr. (2021-2025).

- Inaugural Address - Wednesday, January 20, 2021

Donald J. Trump (2017-2021)

- Inaugural Address - Friday, January 20, 2017

Barack Obama (2009-2017)

- First Inaugural Address - Tuesday, January 20, 2009

- Second Inaugural Address - Monday, January 21, 2013

George W. Bush (2001-2009)

- First Inaugural Address - Saturday, January 20, 2001

- Second Inaugural Address - Thursday, January 20, 2005

William J. Clinton (1993-2001)

- First Inaugural Address - Wednesday, January 20, 1993

- Second Inaugural Address - Monday, January 20, 1997

George Bush (1989-1993)

- Inaugural Address - Friday, January 20, 1989

Ronald Reagan (1981-1989)

- First Inaugural Address - Tuesday, January 20, 1981

- Second Inaugural Address - Monday, January 21, 1985

Jimmy Carter (1977-1981)

- Inaugural Address - Thursday, January 20, 1977

Gerald R. Ford (1974-1977)

- Swearing-In following the Resignation of President Nixon - Friday, August 09, 1974

Richard M. Nixon (1969-1974)

- First Inaugural Address - Monday, January 20, 1969

- Second Inaugural Address - Saturday, January 20, 1973

Lyndon B. Johnson (1963-1969)

- Swearing-In following the Death of President Kennedy - Friday, November 22, 1963

- Inaugural Address - Wednesday, January 20, 1965

John F. Kennedy (1961-1963)

- Inaugural Address - Friday, January 20, 1961

Dwight D. Eisenhower (1953-1961)

- First Inaugural Address - Tuesday, January 20, 1953

- Second Inaugural Address - Monday, January 21, 1957

Harry S. Truman (1949-1953)

- Swearing-In following the Death of President Roosevelt - Thursday, April 12, 1945

- Inaugural Address - Thursday, January 20, 1949

Franklin D. Roosevelt (1933-1945)

- First Inaugural Address - Saturday, March 04, 1933

- Second Inaugural Address - Wednesday, January 20, 1937

- Third Inaugural Address - Monday, January 20, 1941

- Fourth Inaugural Address - Saturday, January 20, 1945

Herbert Hoover (1929-1933)

- Inaugural Address - Monday, March 04, 1929

Calvin Coolidge (1923-1929)

- Swearing-In following the Death of President Harding - Friday, August 03, 1923

- Inaugural Address - Wednesday, March 04, 1925

Warren G. Harding (1921-1923)

- Inaugural Address - Friday, March 04, 1921

Woodrow Wilson (1913-1921)

- First Inaugural Address - Tuesday, March 04, 1913

- Second Inaugural Address - Monday, March 05, 1917

William Howard Taft (1909-1913)

- Inaugural Address - Thursday, March 04, 1909

Theodore Roosevelt (1901-1909)

- Swearing-In following the Assassination of President McKinley - Saturday, September 14, 1901

- Inaugural Address - Saturday, March 04, 1905

William McKinley (1897-1901)

- First Inaugural Address - Thursday, March 04, 1897

- Second Inaugural Address - Monday, March 04, 1901

Grover Cleveland (1893-1897)

- Second Inaugural Address - Saturday, March 04, 1893

Benjamin Harrison (1889-1893)

- Inaugural Address - Monday, March 04, 1889

Grover Cleveland (1885-1889)

- First Inaugural Address - Wednesday, March 04, 1885

Chester Arthur (1881-1885)

- Swearing-In following the Assassination of President Garfield - Tuesday, September 20, 1881

James A. Garfield (1881)

- Inaugural Address - Friday, March 04, 1881

Rutherford B. Hayes (1877-1881)

- Inaugural Address - Monday, March 05, 1877

Ulysses S. Grant (1869-1877)

- First Inaugural Address - Thursday, March 04, 1869

- Second Inaugural Address - Tuesday, March 04, 1873

Mobile Menu Overlay

The White House 1600 Pennsylvania Ave NW Washington, DC 20500

Inaugural Address by President Joseph R. Biden, Jr.

The United States Capitol

11:52 AM EST

THE PRESIDENT: Chief Justice Roberts, Vice President Harris, Speaker Pelosi, Leader Schumer, Leader McConnell, Vice President Pence, distinguished guests, and my fellow Americans.

This is America’s day.

This is democracy’s day.

A day of history and hope.

Of renewal and resolve.

Through a crucible for the ages America has been tested anew and America has risen to the challenge.

Today, we celebrate the triumph not of a candidate, but of a cause, the cause of democracy.

The will of the people has been heard and the will of the people has been heeded.

We have learned again that democracy is precious.

Democracy is fragile.

And at this hour, my friends, democracy has prevailed.

So now, on this hallowed ground where just days ago violence sought to shake this Capitol’s very foundation, we come together as one nation, under God, indivisible, to carry out the peaceful transfer of power as we have for more than two centuries.

We look ahead in our uniquely American way – restless, bold, optimistic – and set our sights on the nation we know we can be and we must be.

I thank my predecessors of both parties for their presence here.

I thank them from the bottom of my heart.

You know the resilience of our Constitution and the strength of our nation.

As does President Carter, who I spoke to last night but who cannot be with us today, but whom we salute for his lifetime of service.

I have just taken the sacred oath each of these patriots took — an oath first sworn by George Washington.

But the American story depends not on any one of us, not on some of us, but on all of us.

On “We the People” who seek a more perfect Union.

This is a great nation and we are a good people.

Over the centuries through storm and strife, in peace and in war, we have come so far. But we still have far to go.

We will press forward with speed and urgency, for we have much to do in this winter of peril and possibility.

Much to repair.

Much to restore.

Much to heal.

Much to build.

And much to gain.

Few periods in our nation’s history have been more challenging or difficult than the one we’re in now.

A once-in-a-century virus silently stalks the country.

It’s taken as many lives in one year as America lost in all of World War II.

Millions of jobs have been lost.

Hundreds of thousands of businesses closed.

A cry for racial justice some 400 years in the making moves us. The dream of justice for all will be deferred no longer.

A cry for survival comes from the planet itself. A cry that can’t be any more desperate or any more clear.

And now, a rise in political extremism, white supremacy, domestic terrorism that we must confront and we will defeat.

To overcome these challenges – to restore the soul and to secure the future of America – requires more than words.

It requires that most elusive of things in a democracy:

In another January in Washington, on New Year’s Day 1863, Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation.

When he put pen to paper, the President said, “If my name ever goes down into history it will be for this act and my whole soul is in it.”

My whole soul is in it.

Today, on this January day, my whole soul is in this:

Bringing America together.

Uniting our people.

And uniting our nation.

I ask every American to join me in this cause.

Uniting to fight the common foes we face:

Anger, resentment, hatred.

Extremism, lawlessness, violence.

Disease, joblessness, hopelessness.

With unity we can do great things. Important things.

We can right wrongs.

We can put people to work in good jobs.

We can teach our children in safe schools.

We can overcome this deadly virus.

We can reward work, rebuild the middle class, and make health care secure for all.

We can deliver racial justice.

We can make America, once again, the leading force for good in the world.

I know speaking of unity can sound to some like a foolish fantasy.

I know the forces that divide us are deep and they are real.

But I also know they are not new.

Our history has been a constant struggle between the American ideal that we are all created equal and the harsh, ugly reality that racism, nativism, fear, and demonization have long torn us apart.

The battle is perennial.

Victory is never assured.

Through the Civil War, the Great Depression, World War, 9/11, through struggle, sacrifice, and setbacks, our “better angels” have always prevailed.

In each of these moments, enough of us came together to carry all of us forward.

And, we can do so now.

History, faith, and reason show the way, the way of unity.

We can see each other not as adversaries but as neighbors.

We can treat each other with dignity and respect.

We can join forces, stop the shouting, and lower the temperature.

For without unity, there is no peace, only bitterness and fury.

No progress, only exhausting outrage.

No nation, only a state of chaos.

This is our historic moment of crisis and challenge, and unity is the path forward.

And, we must meet this moment as the United States of America.

If we do that, I guarantee you, we will not fail.

We have never, ever, ever failed in America when we have acted together.

And so today, at this time and in this place, let us start afresh.

Let us listen to one another.

Hear one another. See one another.

Show respect to one another.

Politics need not be a raging fire destroying everything in its path.

Every disagreement doesn’t have to be a cause for total war.

And, we must reject a culture in which facts themselves are manipulated and even manufactured.

My fellow Americans, we have to be different than this.

America has to be better than this.

And, I believe America is better than this.

Just look around.

Here we stand, in the shadow of a Capitol dome that was completed amid the Civil War, when the Union itself hung in the balance.

Yet we endured and we prevailed.

Here we stand looking out to the great Mall where Dr. King spoke of his dream.

Here we stand, where 108 years ago at another inaugural, thousands of protestors tried to block brave women from marching for the right to vote.

Today, we mark the swearing-in of the first woman in American history elected to national office – Vice President Kamala Harris.

Don’t tell me things can’t change.

Here we stand across the Potomac from Arlington National Cemetery, where heroes who gave the last full measure of devotion rest in eternal peace.

And here we stand, just days after a riotous mob thought they could use violence to silence the will of the people, to stop the work of our democracy, and to drive us from this sacred ground.

That did not happen.

It will never happen.

Not tomorrow.

To all those who supported our campaign I am humbled by the faith you have placed in us.

To all those who did not support us, let me say this: Hear me out as we move forward. Take a measure of me and my heart.

And if you still disagree, so be it.

That’s democracy. That’s America. The right to dissent peaceably, within the guardrails of our Republic, is perhaps our nation’s greatest strength.

Yet hear me clearly: Disagreement must not lead to disunion.

And I pledge this to you: I will be a President for all Americans.

I will fight as hard for those who did not support me as for those who did.

Many centuries ago, Saint Augustine, a saint of my church, wrote that a people was a multitude defined by the common objects of their love.

What are the common objects we love that define us as Americans?

I think I know.

Opportunity.

And, yes, the truth.

Recent weeks and months have taught us a painful lesson.

There is truth and there are lies.

Lies told for power and for profit.

And each of us has a duty and responsibility, as citizens, as Americans, and especially as leaders – leaders who have pledged to honor our Constitution and protect our nation — to defend the truth and to defeat the lies.

I understand that many Americans view the future with some fear and trepidation.

I understand they worry about their jobs, about taking care of their families, about what comes next.

But the answer is not to turn inward, to retreat into competing factions, distrusting those who don’t look like you do, or worship the way you do, or don’t get their news from the same sources you do.

We must end this uncivil war that pits red against blue, rural versus urban, conservative versus liberal.

We can do this if we open our souls instead of hardening our hearts.

If we show a little tolerance and humility.

If we’re willing to stand in the other person’s shoes just for a moment. Because here is the thing about life: There is no accounting for what fate will deal you.

There are some days when we need a hand.

There are other days when we’re called on to lend one.

That is how we must be with one another.

And, if we are this way, our country will be stronger, more prosperous, more ready for the future.

My fellow Americans, in the work ahead of us, we will need each other.

We will need all our strength to persevere through this dark winter.

We are entering what may well be the toughest and deadliest period of the virus.

We must set aside the politics and finally face this pandemic as one nation.

I promise you this: as the Bible says weeping may endure for a night but joy cometh in the morning.

We will get through this, together

The world is watching today.

So here is my message to those beyond our borders: America has been tested and we have come out stronger for it.

We will repair our alliances and engage with the world once again.

Not to meet yesterday’s challenges, but today’s and tomorrow’s.

We will lead not merely by the example of our power but by the power of our example.

We will be a strong and trusted partner for peace, progress, and security.

We have been through so much in this nation.

And, in my first act as President, I would like to ask you to join me in a moment of silent prayer to remember all those we lost this past year to the pandemic.

To those 400,000 fellow Americans – mothers and fathers, husbands and wives, sons and daughters, friends, neighbors, and co-workers.

We will honor them by becoming the people and nation we know we can and should be.

Let us say a silent prayer for those who lost their lives, for those they left behind, and for our country.

This is a time of testing.

We face an attack on democracy and on truth.

A raging virus.

Growing inequity.

The sting of systemic racism.

A climate in crisis.

America’s role in the world.

Any one of these would be enough to challenge us in profound ways.

But the fact is we face them all at once, presenting this nation with the gravest of responsibilities.

Now we must step up.

It is a time for boldness, for there is so much to do.

And, this is certain.

We will be judged, you and I, for how we resolve the cascading crises of our era.

Will we rise to the occasion?

Will we master this rare and difficult hour?

Will we meet our obligations and pass along a new and better world for our children?

I believe we must and I believe we will.

And when we do, we will write the next chapter in the American story.

It’s a story that might sound something like a song that means a lot to me.

It’s called “American Anthem” and there is one verse stands out for me:

“The work and prayers of centuries have brought us to this day What shall be our legacy? What will our children say?… Let me know in my heart When my days are through America America I gave my best to you.”

Let us add our own work and prayers to the unfolding story of our nation.

If we do this then when our days are through our children and our children’s children will say of us they gave their best.

They did their duty.

They healed a broken land. My fellow Americans, I close today where I began, with a sacred oath.

Before God and all of you I give you my word.

I will always level with you.

I will defend the Constitution.

I will defend our democracy.

I will defend America.

I will give my all in your service thinking not of power, but of possibilities.

Not of personal interest, but of the public good.

And together, we shall write an American story of hope, not fear.

Of unity, not division.

Of light, not darkness.

An American story of decency and dignity.

Of love and of healing.

Of greatness and of goodness.

May this be the story that guides us.

The story that inspires us.

The story that tells ages yet to come that we answered the call of history.

We met the moment.

That democracy and hope, truth and justice, did not die on our watch but thrived.

That our America secured liberty at home and stood once again as a beacon to the world.

That is what we owe our forebearers, one another, and generations to follow.

So, with purpose and resolve we turn to the tasks of our time.

Sustained by faith.

Driven by conviction.

And, devoted to one another and to this country we love with all our hearts.

May God bless America and may God protect our troops.

Thank you, America.

12:13 pm EST

Stay Connected

We'll be in touch with the latest information on how President Biden and his administration are working for the American people, as well as ways you can get involved and help our country build back better.

Opt in to send and receive text messages from President Biden.

Will you join us in lighting the way for tomorrow's leaders?

Historic speeches, inaugural address.

Transcripts: [[selectable_languages.length]] Languages

Downloading Tip: Hold the "Alt" or "Option" key when clicking on the link, or right-click and select "Save Link As" to download this file.

About Historic Speech

Digital Identifier: USG-17

Title: Inaugural Address, 20 January 1961

Date(s) of Materials: 20 January 1961

Description: Motion picture of President John F. Kennedy's Inaugural Address in Washington, D.C. Supreme Court Chief Justice Earl Warren administers the oath of office to President Kennedy. Former President Dwight D. Eisenhower and former Vice President Richard M. Nixon congratulate President Kennedy. In his speech President Kennedy urges American citizens to participate in public service and "ask not what your country can do for you--ask what you can do for your country." Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson looks on.

Copyright Status: Public domain

Physical Description: 4 film reels (color; sound; 16 mm; 16 minutes)

Creator: WO#30806, RG274, records of the White House Signal Agency. John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston, Massachusetts.

[[selectable_languages.length]] Languages

Milestone Documents

President John F. Kennedy's Inaugural Address (1961)

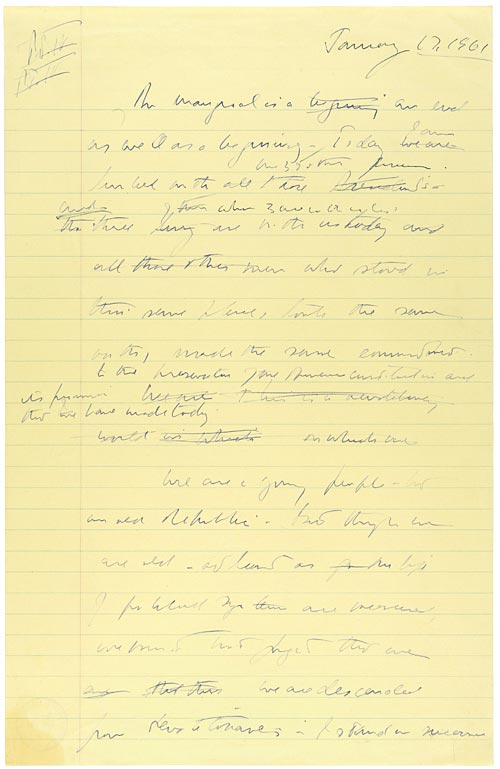

Citation: Inaugural Address, Kennedy Draft, 01/17/1961; Papers of John F. Kennedy: President's Office Files, 01/20/1961-11/22/1963; John F. Kennedy Library; National Archives and Records Administration.

View All Pages in the National Archives Catalog

View Transcript

On January 20, 1961, President John F. Kennedy delivered his inaugural address in which he announced that "we shall pay any price, bear any burden, meet any hardship, support any friend, oppose any foe to assure the survival and success of liberty."

The inaugural ceremony is a defining moment in a president’s career — and no one knew this better than John F. Kennedy as he prepared for his own inauguration on January 20, 1961. He wanted his address to be short and clear, devoid of any partisan rhetoric and focused on foreign policy.

Kennedy began constructing his speech in late November, working from a speech file kept by his secretary and soliciting suggestions from friends and advisors. He wrote his thoughts in his nearly indecipherable longhand on a yellow legal pad.

While his colleagues submitted ideas, the speech was distinctly the work of Kennedy himself. Aides recounted that every sentence was worked, reworked, and reduced. The meticulously crafted piece of oratory dramatically announced a generational change in the White House. It called on the nation to combat "tyranny, poverty, disease, and war itself" and urged American citizens to participate in public service.

The climax of the speech and its most memorable phrase – "Ask not what your country can do for you – ask what you can do for your country" – was honed down from a thought about sacrifice that Kennedy had long held in his mind and had expressed in various ways in campaign speeches.

Less than six weeks after his inauguration, on March 1, President Kennedy issued an executive order establishing the Peace Corps as a pilot program within the Department of State. He envisioned the Peace Corps as a pool of trained American volunteers who would go overseas to help foreign countries meet their needs for skilled manpower. Later that year, Congress passed the Peace Corps Act, making the program permanent.

Teach with this document.

Previous Document Next Document

Vice President Johnson, Mr. Speaker, Mr. Chief Justice, President Eisenhower, Vice President Nixon, President Truman, Reverend Clergy, fellow citizens:

We observe today not a victory of party but a celebration of freedom--symbolizing an end as well as a beginning--signifying renewal as well as change. For I have sworn before you and Almighty God the same solemn oath our forbears prescribed nearly a century and three-quarters ago.

The world is very different now. For man holds in his mortal hands the power to abolish all forms of human poverty and all forms of human life. And yet the same revolutionary beliefs for which our forebears fought are still at issue around the globe--the belief that the rights of man come not from the generosity of the state but from the hand of God.

We dare not forget today that we are the heirs of that first revolution. Let the word go forth from this time and place, to friend and foe alike, that the torch has been passed to a new generation of Americans--born in this century, tempered by war, disciplined by a hard and bitter peace, proud of our ancient heritage--and unwilling to witness or permit the slow undoing of those human rights to which this nation has always been committed, and to which we are committed today at home and around the world.

Let every nation know, whether it wishes us well or ill, that we shall pay any price, bear any burden, meet any hardship, support any friend, oppose any foe to assure the survival and the success of liberty.

This much we pledge--and more.

To those old allies whose cultural and spiritual origins we share, we pledge the loyalty of faithful friends. United there is little we cannot do in a host of cooperative ventures. Divided there is little we can do--for we dare not meet a powerful challenge at odds and split asunder.

To those new states whom we welcome to the ranks of the free, we pledge our word that one form of colonial control shall not have passed away merely to be replaced by a far more iron tyranny. We shall not always expect to find them supporting our view. But we shall always hope to find them strongly supporting their own freedom--and to remember that, in the past, those who foolishly sought power by riding the back of the tiger ended up inside.

To those people in the huts and villages of half the globe struggling to break the bonds of mass misery, we pledge our best efforts to help them help themselves, for whatever period is required--not because the communists may be doing it, not because we seek their votes, but because it is right. If a free society cannot help the many who are poor, it cannot save the few who are rich.

To our sister republics south of our border, we offer a special pledge--to convert our good words into good deeds--in a new alliance for progress--to assist free men and free governments in casting off the chains of poverty. But this peaceful revolution of hope cannot become the prey of hostile powers. Let all our neighbors know that we shall join with them to oppose aggression or subversion anywhere in the Americas. And let every other power know that this Hemisphere intends to remain the master of its own house.

To that world assembly of sovereign states, the United Nations, our last best hope in an age where the instruments of war have far outpaced the instruments of peace, we renew our pledge of support--to prevent it from becoming merely a forum for invective--to strengthen its shield of the new and the weak--and to enlarge the area in which its writ may run.

Finally, to those nations who would make themselves our adversary, we offer not a pledge but a request: that both sides begin anew the quest for peace, before the dark powers of destruction unleashed by science engulf all humanity in planned or accidental self-destruction.

We dare not tempt them with weakness. For only when our arms are sufficient beyond doubt can we be certain beyond doubt that they will never be employed.

But neither can two great and powerful groups of nations take comfort from our present course--both sides overburdened by the cost of modern weapons, both rightly alarmed by the steady spread of the deadly atom, yet both racing to alter that uncertain balance of terror that stays the hand of mankind's final war.

So let us begin anew--remembering on both sides that civility is not a sign of weakness, and sincerity is always subject to proof. Let us never negotiate out of fear. But let us never fear to negotiate.

Let both sides explore what problems unite us instead of belaboring those problems which divide us.

Let both sides, for the first time, formulate serious and precise proposals for the inspection and control of arms--and bring the absolute power to destroy other nations under the absolute control of all nations.

Let both sides seek to invoke the wonders of science instead of its terrors. Together let us explore the stars, conquer the deserts, eradicate disease, tap the ocean depths and encourage the arts and commerce.

Let both sides unite to heed in all corners of the earth the command of Isaiah--to "undo the heavy burdens . . . (and) let the oppressed go free."

And if a beachhead of cooperation may push back the jungle of suspicion, let both sides join in creating a new endeavor, not a new balance of power, but a new world of law, where the strong are just and the weak secure and the peace preserved.

All this will not be finished in the first one hundred days. Nor will it be finished in the first one thousand days, nor in the life of this Administration, nor even perhaps in our lifetime on this planet. But let us begin.

In your hands, my fellow citizens, more than mine, will rest the final success or failure of our course. Since this country was founded, each generation of Americans has been summoned to give testimony to its national loyalty. The graves of young Americans who answered the call to service surround the globe.

Now the trumpet summons us again--not as a call to bear arms, though arms we need--not as a call to battle, though embattled we are-- but a call to bear the burden of a long twilight struggle, year in and year out, "rejoicing in hope, patient in tribulation"--a struggle against the common enemies of man: tyranny, poverty, disease and war itself.

Can we forge against these enemies a grand and global alliance, North and South, East and West, that can assure a more fruitful life for all mankind? Will you join in that historic effort?

In the long history of the world, only a few generations have been granted the role of defending freedom in its hour of maximum danger. I do not shrink from this responsibility--I welcome it. I do not believe that any of us would exchange places with any other people or any other generation. The energy, the faith, the devotion which we bring to this endeavor will light our country and all who serve it--and the glow from that fire can truly light the world.

And so, my fellow Americans: ask not what your country can do for you--ask what you can do for your country.

My fellow citizens of the world: ask not what America will do for you, but what together we can do for the freedom of man.

Finally, whether you are citizens of America or citizens of the world, ask of us here the same high standards of strength and sacrifice which we ask of you. With a good conscience our only sure reward, with history the final judge of our deeds, let us go forth to lead the land we love, asking His blessing and His help, but knowing that here on earth God's work must truly be our own.

What can we help you find?

While we certainly appreciate historical preservation, it looks like your browser is a bit too historic to properly view whitehousehistory.org. — a browser upgrade should do the trick.

Main Content

- K-12 Education Resources and Programs

- Learning Tools and Resources

The Presidential Inauguration: An American Tradition

Join the White House Historical Association for a brief look at the history of presidential inaugural ceremonies and how the events surrounding the swearing in of a new president have become bedrock traditions of the peaceful transfer of power.

You Might Also Like

The History of Wine and the White House

Featuring Frederick J. Ryan, author of “Wine and the White House: A History" and member of the White House Historical Association’s National Council on White House History

America’s Irish Roots

Featuring Geraldine Byrne Nason, Ambassador of Ireland to the United States

Washington National Cathedral & the White House

Featuring Very Reverend Randolph Hollerith and Reverend Canon Jan Naylor Cope

Presidential Leadership Lessons

Featuring Talmage Boston

Blair House: The President’s Guest House

Featuring The Honorable Capricia Marshall, Ambassador Stuart Holliday, and Matthew Wendel

The Carter White House 1977 - 1981

On January 20, 1977, Jimmy Carter was inaugurated as the thirty-ninth president of the United States. During his time in the White House (1977–81), President Carter made many decisions guided by his fundamental commitment to peace and democratic values, emphasizing human and civil rights above all else. Putting these ideals into practice, President Carter negotiated the Camp David Accords, secured the release of Am

Making the Presidential Seal

Featuring Charles Mugno, Thomas Casciaro, and Michael Craghead

The 2024 White House Christmas Ornament

Every year since 1981, the White House Historical Association has had the privilege of designing the Official White House Christmas Ornament. These unique collectibles — honoring individual presidents or specific White House anniversaries — have become part of the holiday tradition for millions of American families. In this collection, explore the history behind our 2024 design and learn more about President Jimmy Carter. Buy the

Conversations on the American Presidency

Featuring David Rubenstein

Queen Elizabeth II and America’s Presidents

Featuring David Charter

The 2023 White House Christmas Ornament

Every year since 1981, the White House Historical Association has had the privilege of designing the Official White House Christmas Ornament. These unique collectibles — honoring individual presidents or specific White House anniversaries — have become part of the holiday tradition for millions of American families. In this collection, explore the history behind our 2023 design and learn more about President Gerald R. Ford. Buy

Olympic Celebrations

Honoring some of the greatest moments in sports history has become a tradition at the White House. Presidents and their families have long recognized athletes as well as the cooperation, competition, and national pride displayed during the summer and winter Olympic and Paralympic Games. Over the years, this has taken on a variety of forms from opening the games to

The Official 2024 White House Christmas Ornament

An official website of the United States government

Here's how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

Welcome to USA.gov

Benefits.gov has been discontinued. USA.gov is the new centralized place for finding government benefits for health care, housing, food, unemployment, and more.

- Continue to USA.gov

Inauguration of the president of the United States

Inauguration Day is the day when the president-elect and vice-president-elect are sworn in and take office.

When is Inauguration Day?

Inauguration Day occurs every four years on January 20 (or January 21 if January 20 falls on a Sunday). The inauguration ceremony takes place at the U.S. Capitol building in Washington, DC. The next presidential inauguration is scheduled to be on January 20, 2025.

What is the presidential oath of office?

The vice-president-elect is sworn in first and repeats the same oath of office, in use since 1884, as senators, representatives, and other federal employees:

"I do solemnly swear (or affirm) that I will support and defend the Constitution of the United States against all enemies, foreign and domestic; that I will bear true faith and allegiance to the same; that I take this obligation freely, without any mental reservation or purpose of evasion; and that I will well and faithfully discharge the duties of the office on which I am about to enter: So help me God."

Around noon, the president-elect recites the following oath in accordance with Article II, Section I of the U.S. Constitution:

"I do solemnly swear (or affirm) that I will faithfully execute the Office of President of the United States, and will to the best of my ability, preserve, protect and defend the Constitution of the United States."

What events take place on Inauguration Day?

The inauguration is planned by the Joint Congressional Committee on Inaugural Ceremonies (JCCIC). Inaugural events include the swearing-in ceremony, the inaugural address, and the pass in review. Learn more about each event from the JCCIC.

For more information on the history of presidential inaugurations, explore the inaugural materials from the collections of the Library of Congress.

How do you get tickets to the presidential inauguration?