An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Overview of Systematic Reviews: Yoga as a Therapeutic Intervention for Adults with Acute and Chronic Health Conditions

Marcy c mccall, alison ward, nia w roberts, carl heneghan.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

*Marcy C. McCall: [email protected]

Academic Editor: Stefanie Joos

Received 2012 Dec 20; Revised 2013 Feb 21; Accepted 2013 Mar 21; Issue date 2013.

This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Objectives . Overview the quality, direction, and characteristics of yoga interventions for treatment of acute and chronic health conditions in adult populations. Methods . We searched for systematic reviews in 10 online databases, bibliographic references, and hand-searches in yoga-related journals. Included reviews satisfy Oxman criteria and specify yoga as a primary intervention in one or more randomized controlled trials for treatment in adults. The AMSTAR tool and GRADE approach evaluated the methodological quality of reviews and quality of evidence. Results . We identified 2202 titles, of which 41 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility and 26 systematic reviews satisfied inclusion criteria. Thirteen systematic reviews include quantitative data and six papers include meta-analysis. The quality of evidence is generally low. Sixteen different types of health conditions are included. Eleven reviews show tendency towards positive effects of yoga intervention, 15 reviews report unclear results, and no, reviews report adverse effects of yoga. Yoga appears most effective for reducing symptoms in anxiety, depression, and pain. Conclusion . Although the quality of systematic reviews is high, the quality of supporting evidence is low. Significant heterogeneity and variability in reporting interventions by type of yoga, settings, and population characteristics limit the generalizability of results.

1. Introduction

Over 30 million people practice yoga, a spiritual and health discipline of Indian origin [ 1 ]. In January 2007, yoga therapy was defined as the “process of empowering individuals to progress toward improved health and well-being through the application of the philosophy and practice of Yoga” [ 2 ]. Nearly 14 million Americans (6.1% of the population) say that a doctor or therapist has recommended yoga to them for their health condition [ 3 ]. In the United Kingdom, national healthcare services promote yoga as a safe and effective way to promote physical activity, improving strength, balance, and flexibility as well as a potential benefit for people with high blood pressure, heart disease, aches and pains, depression, and stress [ 4 ].

Yoga research in medical health literature continues to increase. Over 2000 journal articles in yoga therapy have been published online ( http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed ). In 2012, 274 new yoga articles were added to PubMed, with 46 results after a “systematic review” title search on the US National Library of Medicine. However, the quality and direction of evidence for yoga therapy is unclear. In one clinical review, results show psychological symptoms and disorders (anxiety, depression, and sleep), pain syndromes, autoimmune conditions (asthma, diabetes, and multiple sclerosis), immune conditions (lymphoma and breast cancer), pregnancy conditions, and weight loss are all positively affected by yoga [ 6 ]. An overview from 2010 includes 21 systematic reviews that yield unanimous positive results for just two conditions—cardiovascular risk reduction and depression [ 7 ].

The aim of this overview is to systematically collect, summarize, and evaluate key findings in yoga systematic reviews to determine the strength of evidence in adult health conditions. Components of yoga interventions, the quality and direction of evidence will be investigated for the first time.

2.1. Criteria for Considering Reviews for Inclusion

2.1.1. types of reviews.

Systematic reviews of yoga as a primary intervention to treat any health condition with at least one randomized-controlled trial (RCT) of yoga are included. Any review assessing multiple health conditions is excluded. Included reviews must satisfy all Oxman criteria as follows: state a replicable search method; adequately attempt to retrieve all relevant data; collect the data in a systematic way; analyze and present the results appropriately; consider sources of bias and the quality of evidence [ 48 ]. To allow for sufficient in-depth analysis of each systematic review, publications after June 1, 2012, are not included though considered in the discussion and limitations of the overview.

2.1.2. Types of Participants

As the population of interest, adult participants with a diagnosed and existing acute or chronic health condition are included. Systematic reviews with asymptomatic or otherwise healthy participants and children (<18 years) are excluded to limit the heterogeneity in an already comprehensive overview.

2.1.3. Types of Interventions

Any type of yoga as defined by review authors compared to a control group receiving no intervention or interventions other than yoga is included. A definition for yoga or yoga therapy in research has not been standardized though for the purposes of this overview, authors define yoga as “any movement meditation technique that includes breathing techniques (pranayama) or one or more of the following: physical postures specific to yoga, meditation or chanting (mantra) in the name of yoga.” Allied health or healing arts that are similar to, but do not call themselves, yoga are not included. Martial arts or alternative healing modalities including Karate, Tai Chi, Qigong, reiki, massage, stretching alone, pilates, and acupuncture are not included. Talk therapies including psychological, social, and cognitive behavioral modification strategies are excluded. Systematic reviews that include multiple interventions with yoga are included when the yoga data can be isolated.

2.2. Outcomes

After consultation amongst the authors (M. C. McCall, C. Heneghan, A. Ward), the following list of outcomes are identified for analysis and will be included if authors note them as either primary or secondary outcomes.

2.2.1. Primary Outcomes

All-cause mortality.

Direction and magnitude of disease progression.

Surrogate markers and biomarkers that correlate with disease progression (i.e., blood pressure, resting heart rate, and endocrine levels).

Number of clinical visits and/or hospital utilization rates.

Changes in medication or prescription patterns.

2.2.2. Secondary Outcomes

Self-reported measures of health, coping or other (i.e., HRQL).

Psychosocial or behavioral outcomes.

Cost effectiveness and related evaluations.

2.3. Search Methods for Identification of Reviews

An electronic search of 10 online health databases including Medline, Cochrane Library, and CINAHL was designed by combining natural language and MeSH terms for yoga as the key components, see the Appendix (M. C. McCall, N. Roberts). In addition, hand-searches of relevant journals and journalistic books including The Science of Yoga [ 49 ] and Yoga as Medicine [ 50 ] were conducted. Websites of known yoga research institutes were visited. References and bibliographies of found reviews were searched for additional titles.

2.4. Data Collection and Analysis

2.4.1. selection of reviews.

The first reviewer screened titles, abstracts, and full articles found from electronic and other sources. A second reviewer (C. Heneghan) provided supervision and random assessment of the selection process.

2.4.2. Data Extraction and Management

One reviewer (M. C. McCall) systematically collected and extracted the data to standardized digital collection forms. Two other reviewers (C. Heneghan, A. Ward) independently assessed the accuracy of the data collection. Consensus through discussion or eventual consultation of a third-party resolved any discrepancies. Any missing data is considered a limitation of the overview. In reviews that include multiple interventions and yoga, data is collected on a separate database to allow for independent analysis. In multiple intervention reviews, only yoga-specific data is reported.

2.5. Assessment of Methodological Quality of Included Reviews

We address two aspects of quality for the included reviews: the quality of evidence included in the reviews and the quality of the systematic reviews themselves. The first reviewer performed the quality assessments with supervision from a second author.

2.5.1. Quality of Evidence in Included Reviews

The authors sought to record “Grade of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation” (GRADE) from systematic reviews. When other measures of quality were employed, judgments by first author (M. C. McCall) were made to downgrade or upgrade the quality of evidence based on the amount of potential bias due to study design and other criteria specified in the GRADE toolbox [ 51 ]. Insufficient data was reported in instances where adequate information was unavailable.

2.5.2. Quality of Included Reviews

The authors implemented the “assessment of multiple systematic reviews” (AMSTAR) measurement tool [ 52 ].

2.6. Data Synthesis

Characteristics of all included reviews and the overview of reviews tables summarize the key findings of data collection. The summary of results includes a narrative analysis and quantitative information, where possible. Given sufficient data, the following subgroups are identified for analysis: gender, age, ethnicity, interventions by type of practice, mode of delivery, setting, duration of sessions, duration of interventions, and intensity in terms of physiological effort such as caloric expenditure or cardiovascular output.

3.1. Description of Included Reviews

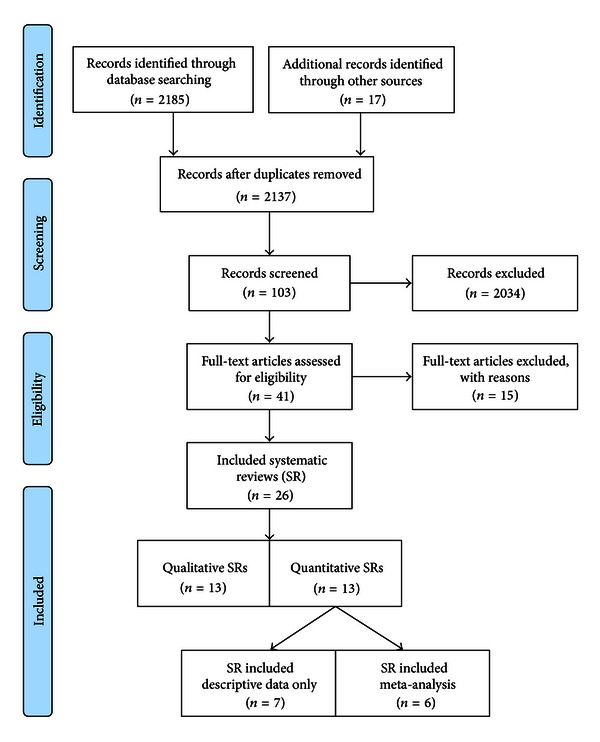

Twenty-six systematic reviews are included in this overview. Six systematic reviews provide quantitative data with meta-analyses, seven reviews provide descriptive data with no pooled analysis, and 13 reviews contain qualitative descriptions of results. Twelve systematic reviews include only yoga interventions. Figure 1 outlines the selection process in an article flow diagram. Refer to Table 1 for characteristics of included reviews. See additional Table 2 for full list of reviews and reasons for exclusion. The systematic reviews include evidence from 125 primary studies, of which 92 studies include only yoga interventions.

Flowchart of systematic review selection [ 5 ].

Characteristics of included systematic reviews.

Italics: systematic reviews including only yoga interventions.

Normal: systematic reviews including yoga interventions plus other interventions.

Characteristics of excluded reviews (ordered by review author).

3.1.1. Population

The total number of participants across all studies is 5915. Six reviews do not include studies with sample sizes greater than 50 participants at baseline. The age range of participants is 18 to 77 years. Mean age, gender, ethnicity, or socioeconomic status of the sample population is unavailable due to insufficient reporting, although the majority of participants are women.

Twelve systematic reviews investigate only yoga interventions and include the following health conditions: anxiety (4 reviews), pain management (2 reviews), with one review each in depression, epilepsy, psychiatric disorder, diabetes, arthritis, and relief of menopause symptoms. The 14 systematic reviews that include yoga therapy in combination with other interventions measured health outcomes in carpal tunnel syndrome and diabetes risk factors (2 reviews each), with one review each in anxiety, asthma, chronic kidney disease, fibromyalgia, hypertension, low back pain, menopause, pain management in labor, chronic pain, and osteoarthritis.

3.1.2. Length of Intervention and Followup

Of 25 reporting systematic reviews, one (with 2 primary studies) includes only trials ≥24 weeks duration. Follow-up measures are mentioned in eight of the 26 reviews, where four report on primary studies that include follow-up measures ≥12 weeks, two report follow-up measures <12 weeks, and two report no follow-up evaluations.

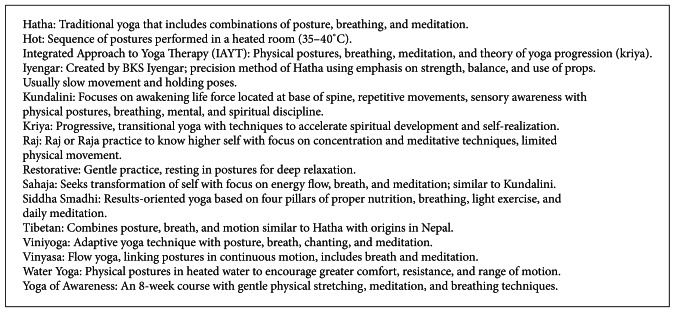

3.1.3. Characteristics of Intervention

Twenty-two systematic reviews include any type of yoga intervention. Two systematic reviews include only Kundalini yoga [ 18 , 19 ] one systematic review each includes only Restorative yoga [ 9 ] and Yoga of Awareness [ 20 ]. The other types of yoga intervention are listed in Box 2 include: Viniyoga, Integrated yoga, Raj, Iyengar, Kriya, Sahaja, Siddha Samadhi, hot, water, and Tibetan yoga. Modified, non-descriptive, or unspecified yoga interventions are included in 12 systematic reviews. Interventions of Ashtanga, power, or flow yoga are not found. The most prevalent yoga intervention by type includes Iyengar (9 reviews), Hatha (7 reviews) Restorative (5), and Kundalini and Integrated yoga (3 reviews each).

Types of yoga intervention.

Nine of the systematic reviews do not report on the type of delivery mechanism of yoga used in their primary studies. Instructor-led yoga is identified in a majority of cases (17 reviews), independent or home study (13 reviews), book-led yoga (5 reviews), audio-led yoga (4 reviews), and video-led yoga in one review. No review evaluates the effect of yoga by type or delivery mechanism for a specific health condition. Twenty reviews report the duration and frequency of yoga sessions. The duration of yoga sessions varies between 20 and 300 minutes, an intervention of 60 minutes in length most prevalent. Seven reviews include yoga interventions with <3 yoga sessions per week, three reviews include only yoga interventions with ≥3 sessions per week, and 10 reviews include both frequencies of yoga sessions. Systematic reviews do not report on the intensity of yoga interventions in terms of physiological effort such as cardiac output or caloric expenditure.

3.1.4. Comparisons

Fourteen of the 26 systematic reviews (28 primary studies) report a waitlist as comparison for treatment for yoga. Other kinds of exercise are compared to yoga in 11 systematic reviews (19 primary studies), nine systematic reviews (16 primary studies) identify usual care, while medicinal intervention is noted in three reviews (4 primary studies). Four systematic reviews (19 studies) do not report the use of control groups or comparisons. Other comparisons reported in the reviews include disseminating reading material (5 reviews, 5 studies), sham yoga (3 reviews, 5 studies), talk therapy (2 reviews, 3 studies), and lectures (2 reviews, 2 studies).

3.2. Methodological Quality of Included Reviews

3.2.1. quality of included reviews.

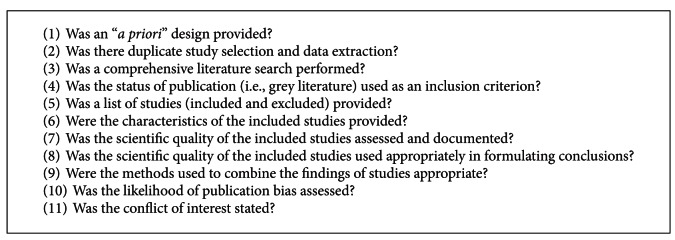

The overall quality of systematic reviews is high (AMSTAR average = 9.4). Fifteen of the reviews are considered of very high quality (AMSTAR ≥ 10), 6 of high quality (AMSTAR 8–9.9), 5 reviews of medium quality (4–7.9 AMSTAR), and no systematic review scores below 4 points. See Table 3 for the AMSTAR ratings of the included systematic reviews. All 26 reviews scored in five of eleven methodological criteria including (refer to Box 1 ): identification of a priori design, using duplicate referees for study selection and data extraction, implementing a comprehensive literature search, considering the status of publication for inclusion, and the assessment and documentation of the scientific quality of evidence. The characteristics of included studies, respective quality, and the methods to combine findings of those studies are appropriate in 21 reviews. Lists of excluded studies and conflicts of interest are inconsistently reported (16 reviews only). A statistical investigation to determine a likelihood of bias is most poorly reported (2 of 12 yoga—only reviews).

Overview of reviews: quality and outcomes summary.

The AMSTAR tool criteria.

3.2.2. Quality of Evidence in Included Reviews

The quality of evidence ranges from very poor/low to moderate quality (see Table 3 ). No high-quality evidence is included in the reviews. Systematic review authors implement a diverse set of tools to evaluate evidence, including Jadad scores, CONSORT guidelines, and PEDro scales. In 16 systematic reviews, the GRADE approach is applied to uniform results, while 10 reviews did not provide sufficient data to independently assess their quality of evidence.

3.3. Effects of Interventions

3.3.1. all-cause mortality.

Outcome results for all-cause mortality are not studied in the reviews. The absence of data could be due to characteristics of study design including length of trials (typically 3–6 months) and small sample sizes ( n < 50). The population samples usually include middle-aged adults receiving treatment for chronic illnesses; thus, mortality may be limited in such groups, or yoga therapy may have no effect on reducing mortality.

3.3.2. Direction and Magnitude of Disease Progression

Nine reviews measure the direction and magnitude of disease progression. These chronic diseases include anxiety [ 18 , 19 ], depression [ 27 ], treatment of psychiatric disorder [ 11 ], clinical outcomes in arthritis [ 14 ] and osteoarthritis [ 23 ], carpal tunnel syndrome [ 26 ], epilepsy [ 30 ], and asthma [ 29 ]. Included studies of yoga therapy are characteristically short in duration, which will contribute to the lack of available evidence to analyze this outcome.

3.3.3. Surrogate Markers and Biomarkers That Correlate with Disease Progression (i.e., Blood Pressure, Resting Heart Rate, and Endocrine Levels)

Five systematic reviews measure surrogate markers that correlate with disease progression including blood pressure [ 12 ], body mass index [ 9 ], metabolic and anthropometric measures for diabetes mellitus [ 16 ], fasting blood glucose [ 8 ] and muscular strength [ 15 ]. Higher quality research with controlled clinical trials report a 6.9% reduction in fasting glucose of adults with diabetes and 7.8% reduction in body weight, with reductions in systolic and diastolic blood pressures ranging from 3.9 to 13.9% and 5.8 to 15.8% for adults with diabetes or at risk of CVD [ 16 ]. Although an average decrease of 3/5 mmHg is found in hypertensive patients, Dickinson et al. suggest no good evidence exists to confirm yoga therapy is effective for treatment of hypertension as studies are too small to detect any effect on morbidity or mortality. Study designs lack blinding and use inadequate randomization techniques, thus potential biases and limitations characterizing most of these studies hinder interpretation of findings [ 8 , 9 , 15 , 16 ].

3.3.4. Number of Clinical Visits and/or Hospital Utilization Rates

Systematic reviews do not report changes in number of clinical visits and/or hospital utilization rates with yoga intervention. Although a number of interventions are implemented in a clinical setting (9 of 26 reviews), it is possible that primary researchers did not collect data regarding hospital referral rates, perhaps due to limited resources or short-time horizons.

3.3.5. Changes in Medication or Prescription Patterns

Two systematic reviews measure changes in medication with yoga intervention [ 16 , 28 ]. One author concludes that yoga may be beneficial in decreasing medication usage in diabetes [ 16 ]; the second study concludes with caution that yoga may decrease medication usage in pain conditions, although results were not statistically significant [ 28 ].

3.3.6. Self-Reported Measures of Health, Coping or Other (i.e., HRQL)

Twelve systematic reviews include self-reported measures for pain management [ 10 , 13 , 20 , 22 , 24 , 25 , 28 , 31 , 33 ], menopausal symptoms [ 17 , 21 ], perceived stress [ 25 ], psychological wellbeing, and quality of life for cancer patients [ 22 , 32 ]. Seven review authors conclude positive effects [ 10 , 17 , 20 , 22 , 24 , 28 , 32 ]. One RCT with treatment of low-back pain shows that Iyengar yoga ( n = 60) can reduce pain intensity (64%), functional disability (77%), and pain medication usage (88%) versus the education control group with usual care [ 10 ]. The overview of various pain conditions (headaches, back pain, muscle soreness, labor, and arthritis) yields a moderate effect size of yoga as measured by visual analog scales and questionnaires (VAS, CMDQ, and PPI) at SMD −0.74 (95%CI, − 0.97 to − 0.52; P < 0.0001) [ 10 ]. Quality of life for cancer patients in yoga groups approaches significance ( P = 0.06) with an SMD −0.29 (95% CI, −0.58 to 0.01) while psychological health outcomes (anxiety, depression, distress, stress) show a pooled effect size of SMD −0.95 (95% CI, − 1.63 to − 0.27; P = 0.006) as measured by HADS, PSS, STAI, POMS, CES-D, PANAS, IES, SCL-90-R, SOSI and the distressed mood index. An earlier review (search date of April 2008) reports encouraging preliminary results for cancer patients with effect sizes that range from 0.04 to 4.67 (anxiety) and 0.17 to 7.44 (depression) in favor of yoga with concurrent treatment, though statistical significance and measuring tools are not reported [ 32 ].

Attributed to the lack of scientific rigor in large-scale and long-term studies, four reviews conclude neutral or unknown effects of yoga intervention for pain in carpal tunnel syndrome [ 13 ], pain in low back [ 31 ], in older adults [ 25 ], and for labor management [ 33 ].

3.3.7. Psychosocial or Behavioral Outcomes

Systematic reviews do not report results on psychosocial or behavioral outcomes.

3.3.8. Cost Effectiveness and Related Evaluations

Systematic reviews do not include results on cost effectiveness and related evaluations. This narrow focus is in part due to early research development and potential lack of funding to implement trials with several outcome measures.

3.4. Quantitative Reports

3.4.1. meta-analyses.

Of the six reviews that included a meta-analysis of results, three investigate outcomes in pain [ 10 , 20 , 31 ], one review each in psychiatric disorders [ 11 ], menopausal symptoms [ 21 ], and psychological health in cancer patients [ 22 ]. For pain studies, interventions include Hatha, Iyengar, Yoga of Awareness, water yoga, Viniyoga, and unspecified yoga programs. Comparisons with physical activity, education sessions, waiting lists, routine care, and talk therapy show unanimously positive results for yoga in pain reduction [ 10 , 20 , 31 ]. These results suggest a moderate effect size of yoga to reduce acute pain in adult populations SMD −0.74 (95% CI, −0.97 to −0.52), in fibromyalgia patients SMD −0.54 (95% CI, −0.96 to −0.11) and low-back pain versus education, self-care, and no exercise. Conversely, yoga did not indicate positive results for menopausal symptoms including pain, psychological wellbeing, and quality of life [ 21 ].

As an adjunct therapy, Cabral et al. conclude that yoga improves treatment of depression, anxiety, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and schizophrenia, with a pooled effect size of SMD −3.25 (95% CI, − 5.36 to − 1.14; P = 0.002). Pranayama techniques are implicated as most important for anxiety and stress-related disorders [ 11 ]. See Table 4 for overview of reviews with pooled results.

Overview of reviews—primary outcomes (yoga meta-analyses).

n.r: not reported; BDI: Beck Depression Inventory; VAS: Visual Analogue Scale; MENSI: Menopausal Self-inventory; MPQ: McGill pain questionnaire; PPI: Present Pain Index; CMDQ: Cornell Musculoskeletal Discomfort Questionnaire; HADS: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; PSS: Perceived Stress Scale; STAI: State of Trait Anxiety Inventory; SOSI: Symptoms of stress inventory; POMS: Profile of Mood States; SCL-90-R: Symptoms Checklist Revised; CES-D: Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; PANAS: Positive and Negative Affect Schedule; IES: Impact of Events Scale; DMI: Distressed Mood Index; SF-36: Medical Outcomes Study Short-Form Health Survey; SF-12: The 12-Item Short Form Health Survey; FACT_B: Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Breast; FACT_G: Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General; EORTC QLQ-C30: European Organization for research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Version 3.0; MBSR: Mindfulness-based stress reduction.

*Average Jadad score.

**Average PEDro scale.

3.4.2. Independent Study Reports (No Pooled Analysis)

Descriptive quantitative data of yoga primary studies is provided in seven reviews. Three of these reviews test the direction and magnitude of disease progression with yoga intervention for anxiety [ 18 ], asthma symptoms [ 29 ], and seizure frequency in epileptics [ 30 ]. Heiwe and Jacobson [ 15 ] measure muscular strength for chronic kidney disease patients. Self-reported measure of pain is included in two reviews [ 13 , 32 ] and perceived stress [ 24 ].

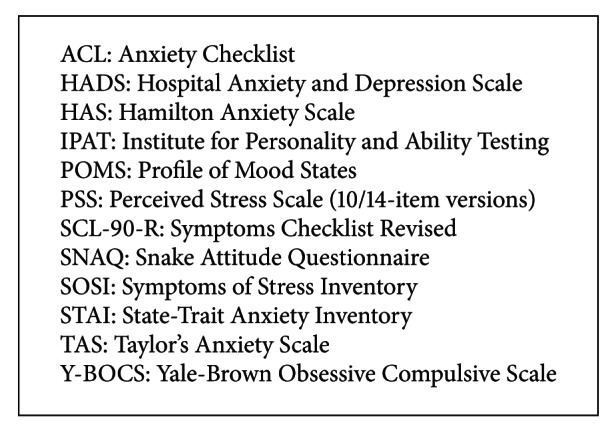

Anxiety outcome measures in the quantitative reviews include Y-BOCS, HAS, IPAT, TAS, ACL, STAI, and SNAQ (see Box 3 ). In general, review results show small reduction in means for yoga groups versus control groups, although the study design varies. One nonrandomized controlled study ( n = 71) reports anxiety neurosis (HAS) decreases with yoga treatment versus placebo capsule SMD 0.89 (95% CI, 0.34 to 1.44; P = 0.001). A smaller randomized control trial measures Y-BOCS ( n = 22) reports SMD 1.10 (95% CI, − 0.02 to 2.22; P = n.r). In patients with cancer, a number of yoga interventions decrease anxiety scores (HADS, PSS, STAI SOSI, POMS, and SCL-90-R). One study reports a decrease of anxiety of SMD −0.76 (95% CI, − 1.34 to − 0.19; P = 0.009) in comparison to wait-list controls. In the two reviews that assess clinical anxiety as an outcome ( n = 1087), results range from having no beneficial effect on STAI scores SMD 0.33 (95% CI, −0.31 to 0.97) to a significant effect size of SMD −4.78 (95% CI, − 5.83 to − 3.74; P = n.r) on HADS and PSS validated questionnaires. Variations in scientific characteristics including the type and duration of intervention and size of samples may account for the variation in results. Weekly Tibetan yoga showed no benefit, while integrated yoga methods including asana, pranayama, and guided relaxation for 90 minutes per week show the greatest benefit in anxious participants.

Summary of anxiety outcome measures.

In pain reviews, Gerritsen et al. review conservative treatment outcomes for carpal tunnel syndrome and report no significant differences in pain after 8 weeks of yoga intervention. Smith et al. [ 33 ] suggest that women receiving yoga report increased satisfaction with pain relief, increased satisfaction with the childbirth experience with reduced pain intensity outcomes in self-reported visual analogue scales (VASTC, MCQ, VASPS) of MD −6.12 (95% CI, −11.77 to − 0.47; P = 0.034) in latent phase labor versus usual care ( n = 66). See Box 4 for summary of measures for pain outcomes.

Summary of outcome measures for pain.

In asthmatic populations, one small study ( n = 36) reports a decrease in exacerbations (episodes per week) WMD −1.27 (95% CI, −2.26 to 0.28) following yoga breathing techniques, although results are not statistically significant [ 29 ]. The hypothesis that yoga breathing can reduce asthmatic episodes is neither confirmed nor refuted with results and further randomized controlled trials are requested.

In one study of epileptic patients ( n = 20), sahaja yoga intervention (versus sham yoga) increases probability of being seizure-free following six months of treatment by 40% with OR 14.54 (95% CI, 0.67 to 316.69; P = 0.089). The same study shows a greater than 50% reduction of seizure duration after six months in 7 of 10 yoga participants versus 0 of 10 sham yoga participants, OR 45.00 (95% CI, 2.01 to 1006.75; P = 0.016). The review author includes a second study that compares Acceptance Commitment Therapy (ACT) and yoga in-seizure outcomes. Five of 10 ACT participants versus 4 of 8 yoga participants are seizure-free after six months, with 50% or greater reduction in seizure duration in 6 of 10 (ACT) and 4 of 8 (yoga) groups, respectively. The review authors conclude that no reliable conclusions can be drawn regarding the efficacy of yoga for treatment of epilepsy due to the small number and size of studies.

In a review on chronic kidney disease populations, a small yoga study ( n = 37) does not show any significant increase in muscular strength for yoga versus control (no exercise/placebo exercise). This review studies a special population in which yoga-related studies are limited.

3.5. Subgroup Analysis

The most commonly cited health outcomes in yoga research are self-reported measures in pain (7 reviews), anxiety (6 reviews), and diabetes management (3 reviews). Five reviews measuring pain outcomes after yoga intervention report positive results. Iyengar (9 reviews), Hatha (7 reviews), and Restorative yoga (5 reviews) through instructor-led sessions (17 reviews) are most common in yoga interventions by type. Six positive effects are concluded in each of the groups of Hatha and Iyengar systematic reviews.

The Büssing et al. review includes meta-analyses on effects sizes for pain according to study design, duration of treatment, quality of study, and type of pain condition. Results suggest that randomized controlled trials with SMD −0.82 (95% CI, −1.20 to 0.53) and higher quality evidence SMD −0.88 (95% CI, 1.55 to −0.21) have marginally better pain outcomes than overall effects at −0.74 (95% CI, −0.97 to −0.52), while treatment duration appears to be similar to these overall effects in short, medium, and long interventions. Authors suggest improvements are most consistent for back pain and rheumatoid arthritic conditions. The remaining reviews do not provide enough data to perform subgroup analyses for gender, age, setting, or physiological intensity of yoga intervention.

4. Discussion

4.1. summary of main results.

The following 13 chronic health conditions in adult populations are included in this overview: anxiety, arthritis, asthma, carpal tunnel syndrome, diabetes, epilepsy, fibromyalgia, hypertension, kidney disease, metabolic syndrome, pain, psychological health in cancer patients, and psychiatric disorders. Acute health conditions are included for women in pregnancy, labor, and menopause.

4.1.1. Interventions and Outcomes

Systematic reviews list some components of yoga interventions: breathing exercises (pranayama), physical postures (asanas), meditation (dhyana) and some yoga philosophy including sahaja (spontaneous movement), yama (personal restraint), and niyama (observance of yoga) teachings. Inconsistent reporting of changes in effect sizes of yoga by intervention type, delivery mechanism, setting, frequency, or duration of sessions highlights a serious gap in the literature and serious limitation in the overview findings. Of 13 systematic reviews that report geographical location, all include data collected from patients in North America, five include participants from Asia, and three reviews include studies from Europe. Fifteen reviews did not provide information on the setting of the intervention. Nine systematic reviews included delivery in a clinic or hospital setting, while two include a home-based intervention and one community-based intervention.

As yoga research remains in the early stages of development, researchers appear to be more concentrated on outcome effects with clinical endpoints. However, traditional yoga practitioners claim that positive influence occurs in several health-related areas such as eliminating alcohol use, encouraging vegetarian diets, and providing an opportunity to increase social cohesion and positive group effects. These outcomes could relate more to mediating effects of yoga and warrant further investigation.

4.1.2. Unclear Effects of Yoga—15 Systematic Reviews

The following outcomes were associated with unclear effects following yoga intervention: anxiety [ 18 , 19 ], arthritis [ 14 , 23 ], asthma [ 29 ], body mass index [ 9 ], diabetes management [ 8 , 16 ], muscular strength [ 15 ], epilepsy [ 30 ], hypertension [ 12 ], and in pain for the elderly population [ 25 ]. Conclusions for menopause and carpal tunnel syndromes were split between positive and unclear effects. The more recent reviews in both instances show positive effects.

4.1.3. Positive Effects of Yoga—11 Systematic Reviews

Seven of the systematic reviews assess pain management as a primary outcome. Of these reviews, 5 authors conclude positive effects of yoga [ 10 , 20 , 28 , 31 , 33 ]. Positive results for the treatment fibromyalgia are noted in one systematic review [ 20 ]. Potential improvements for anxiety and quality of life in cancer patients are noted in two reviews [ 22 , 33 ]. One systematic review in psychiatric disorders concludes that yoga may be an effective and far less toxic adjunct treatment option for severe mental illness to prevent weight gain and patients' risk for cardiovascular disease [ 11 ].

4.1.4. Adverse Effects of Yoga—No Systematic Reviews

Systematic reviews universally report that yoga is safe and no adverse effects of yoga treatment are reported. As yoga therapy in the reviews was usually instructor-led in a clinical setting, yoga delivered without a trained instructor may increase risk of injury and other adverse events.

4.1.5. Size of Effect

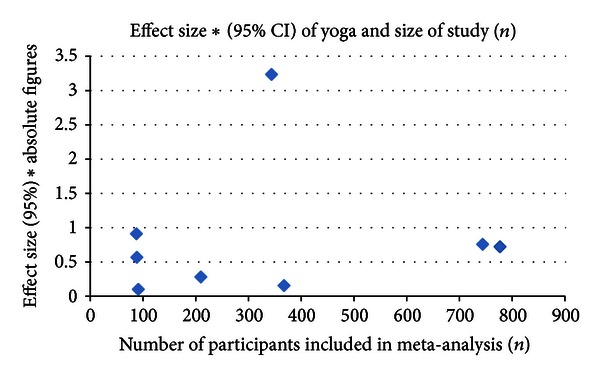

In pooled analyses, statistical data report positive effects in five of six primary health outcomes for pain and various psychiatric disorders (depression, anxiety, PTSD, and schizophrenia). Effect sizes range from SMD −0.54 (95% CI, − 0.96 to − 0.11; P = 0.01) for pain in fibromyalgia patients (VAS) and SMD −3.25 (95% CI, − 5.36 to − 1.14; P = 0.002) in various psychiatric disorders (BDI, HADS, etc.). In the first instance, water yoga and awareness of yoga versus waitlist and treatment shows benefit. Ten studies using integrated yoga, Sudarshan, Kriya, Hatha, and Iyengar techniques favor yoga over other treatments and control groups, although the details are not reported. Most of the systematic reviews cite methodological weaknesses for unclear results, attributing this to small sample sizes and limited numbers of high-quality studies available for review. To investigate the impact of study size and quality on yoga's effect size on health outcomes, see Figure 2 . Although limited by six quantitative data points, it does not appear that study size correlates with yoga's size of effect.

Effect size of yoga in comparison to study size.

4.2. Limitations of This Review

4.2.1. data characteristics.

The quality and quantity of evidence is a limitation to this overview. Though the quality of systematic reviews is high (9.4 AMSTAR), the quality of evidence included in reviews is generally low (GRADE). Important variables such as population statistics including gender, age, duration of interventions, comorbidities, and socioeconomic status are often not reported, limiting the potential for subgroup and meta-analyses. Of the primary and secondary outcome measures reviewed, no reports for all-cause mortality, hospital referral rates, cost effectiveness, or psychosocial behavioral changes are included which suggests at least four areas of potential investigation.

In two reviews that assess publication bias, one funnel plot that includes pain outcomes [ 10 ] did not reveal any significant symmetry, while the other review for psychiatric disorders indicates an asymmetric plot and publication bias [ 11 ]. The remaining 24 reviews do not provide results of Egger's regression, funnel plot, or critical analysis of publication bias; therefore, the degree to which positive outcomes are influenced by publication bias is not known.

As all reports are written in English and the majority of reviews found on electronic databases include studies from the Western hemisphere, it is possible that existing reviews have been missed. The transferability of results may be limited due to only partial descriptions of interventions such as asana, pranayama, and meditative techniques. A broader definition of “systematic review” might increase the number of reviews included from diverse backgrounds, though strict criteria in terms of systematic review quality limits the inclusion of low-quality reports. Missing data for follow-up measures, characteristics of yoga intervention, and components of yoga therapy limit the confidence and number of conclusions that can be drawn, though this lack of data may be due to weakness in sources from primary studies and not necessarily a flaw in systematic review methodology.

4.2.2. Sources of Heterogeneity

Review authors identify types of yoga intervention, population characteristics, outcome measures, and study designs as sources of heterogeneity. As a result of this heterogeneity, most reviews consider independent studies in their analyses. Results are pooled in only six instances, where statistical heterogeneity was found in three cases and one did not report. As a complex intervention, some heterogeneity is inevitable with yoga and in fact desirable to replicate real-life circumstances. Study designs could be improved to focus on specific interventions.

4.2.3. Duplication of Primary Studies

Duplication of primary studies appears in 40 cases across 17 reviews (yoga-only reviews: [ 8 , 11 , 14 , 18 , 21 , 27 , 28 , 53 ]; multiple interventions: [ 13 , 16 , 17 , 23 – 26 , 31 , 33 ]). The highest incidence of primary study overlap occurs in pain [ 25 , 53 ] and menopause reviews [ 17 , 21 ]. In further analysis, when the Garfinkel studies are removed, two systematic reviews are eliminated from this review [ 23 , 26 ]. For pain, the more recent Bussing study concludes positive effects with yoga intervention, while Morone concludes unclear effects using similar studies. The removal of these two studies from the pool of results does not appear to change the net positive effects of yoga for pain conditions. In menopause, although 4 of 7 articles in each review are duplicates, authors' conclude different results: Lee et al. [ 21 ] suggest unclear effects of yoga, while Innes et al. [ 17 ] suggest positive effects of yoga on menopausal symptoms.

4.2.4. Date of Search

The rate of publication for yoga systematic reviews is increasing rapidly. In an updated search (March 1, 2013), nine of 17 new titles pass initial screening for inclusion. Screening of abstracts identifies seven of these reviews that would need to be collected for further inclusion analysis, of which three focus on adult cancer [ 54 – 56 ], one on chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [ 57 ], one for depression [ 58 ], one for anxiety [ 59 ], and one for phantom limb pain [ 60 ]. These reviews suggest positive impact of yoga for primary outcomes with no adverse effects, though authors unanimously state that more and better-quality research is needed. In a recent overview of yoga, authors conclude there is relatively high-quality evidence to suggest that yoga may have beneficial effects for pain-associated disability and mental health [ 53 ], conclusions that are further substantiated by this overview.

5. Conclusion

5.1. implications for practice.

Yoga for treatment of acute and chronic health conditions is not likely to exacerbate symptoms in an experimental setting, although clear effect sizes and probabilities for beneficial outcomes in a specified population are not available at this time. Cumulative findings indicate that Hatha and Restorative yoga have the highest correlation with positive outcomes for managing pain symptoms, anxiety, and depression. Home study and instructor-led yoga (practiced 60 minutes 3 times per week) appear to have similar positive impacts.

5.2. Implications for Research

This overview adds a comprehensive and methodical examination of yoga interventions in adult populations for treatment of acute and chronic health conditions. The findings do support earlier claims that depression, pain, and anxiety could be positively affected by yoga intervention, though evidence is positive but less significant in populations with cardiovascular risk factors, fibromyalgia, or autoimmune disease. It is evident that systematic reviewers and primary research teams should include more information with regards to the characteristics of yoga intervention, including type, frequency, duration, and physiological intensity of practice. Video-led yoga needs to be explored further as one review includes this delivery mechanism and yields positive results, though the sample size is small and adverse effects are not measured. Health outcomes in other adult populations for asthma, arthritis, carpal tunnel syndrome, epilepsy, diabetes, kidney disease, and menopausal women remain uncertain. Two earlier reviews (before June 1, 2012) and three newer systematic reviews investigate yoga's effect for adult cancer. These papers should inform future investigations in terms of patient-relevant outcomes such as pain management, immunological responses, anxiety, and health-related quality of life.

Yoga is a complex intervention that includes physical movement, breathing techniques, meditation, visualization and philosophical underpinnings that may influence attitudes, beliefs and social interaction. A new hypothesis informed by results of this overview, together with an emerging trend of increased yoga research for cancer populations, suggest the complex and varied nature of yoga may better serve patients who experience a cluster of symptoms that include psychological distress, fatigue, pain and a compromised health-related quality of life. Further study into these effects should include analysis of adherence rates, outcomes in morbidity, mortality rates, disease progression markers, physical function and long-term follow-up.

Acknowledgments

This overview was performed in partial requirement of a research doctorate in Evidence-Based Health Care, Department of Continuing Education, Kellogg College at the University of Oxford. Special thanks are due to Professor Mike Clarke and other Evidence-Based Health Care faculty and students for their support in developing the question and research methods.

Electronic Search Protocol

Identification of Relevant Databases:

Cochrane Library

The Electronic Search Performed in May 2012

Online access via SOLO [ http://solo.bodleian.ox.ac.uk with SSO password]

Enter free text terms, MeSH descriptors and set filters

Scan results for relevant titles

Scan titles for relevant abstracts

Scan abstract for relevant review articles

Save citations with abstracts to a file and transfer to reference management database [sente]

Collect relevant articles in.pdf and save to file on external and internal computer hard drives under review identification label

Store the external hard drive in separate location under lock and key. Two key holders.

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (via Cochrane Library, Wiley)

1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6.

MEDLINE (1946-), EMBASE (1974-), AMED (1985-), PsycINFO (1960-) (via OVID)

MeSH descriptor; Meditation; Relaxation Therapy; Mind Body Medicine explode all trees

(yoga OR yogi* OR asana OR pranayama OR dhyana OR meditation)

MeSH descriptor; Meta-analysis; Review explode all trees

(systematic OR review OR meta-analysis)

CINAHL (via EBSCOHost)

limit: publication type (meta-analysis); exclude (MEDLINE results)

IndMED ( http://indmed.nic.in ); CAMQuest ( http://www.cam-quest.org/en/ )

Scopus (via SciVerse; Elsevier)

limit: publication type (review)

- 1. Dangerfield A. Yoga wars. BBC News Magazine, 2009, http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/7844691.stm .

- 2. Taylor M. What is yoga therapy? An IAYT definition. Yoga Therapy in Practice, 2012, http://www.iayt.org/site_Vx2/publications/articles/IAYT%20Yoga%20therapy%20definition%20Dec%202007%20YTIP.pdf .

- 3. Macy D. Yoga Journal Releases 2008 “Yoga in America” market study. Yoga Journal Magazine, 2008, http://www.yogajournal.com/advertise/press_releases/10 .

- 4. National Health Service. NHS: your health, your choices. A Guide to Yoga, 2012, http://www.nhs.uk/livewell/fitness/pages/yoga.aspx .

- 5. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLOS Medicine. 2009;6(6)e1000097 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. Field T. Yoga clinical research review. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice. 2011;17(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2010.09.007. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 7. Ernst E, Lee MS. How effective is yoga? A concise overview of systematic reviews. Focus on Alternative and Complementary Therapies. 2010;15(4):274–279. [ Google Scholar ]

- 8. Aljasir B, Bryson M, Al-Shehri B. Yoga practice for the management of type II diabetes mellitus in adults: a systematic review. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2010;7(4):399–408. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nen027. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. Anderson JG, Taylor AG. The metabolic syndrome and mind-body therapies: a systematic review. Journal of Nutrition and Metabolism. 2011;2011:8 pages. doi: 10.1155/2011/276419.276419 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 10. Büssing A, Ostermann T, Lüdtke R, Michalsen A. Effects of yoga interventions on pain and pain-associated disability: a meta-analysis. Journal of Pain. 2012;13(1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2011.10.001. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 11. Cabral P, Meyer HB, Ames D. Effectiveness of yoga therapy as a complementary treatment for major psychiatric disorders: a meta-analysis. Primary Care Companion For Central Nervous System Disorders. 2011;13(4) doi: 10.4088/PCC.10r01068. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 12. Dickinson HO, Campbell F, Beyer FR, et al. Relaxation therapies for the management of primary hypertension in adults: a Cochrane review. Journal of Human Hypertension. 2008;22(12):809–820. doi: 10.1038/jhh.2008.65. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 13. Gerritsen AA, De Krom MCTFM, Struijs MA, Scholten RJPM, De Vet HCW, Bouter LM. Conservative treatment options for carpal tunnel syndrome: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Journal of Neurology. 2002;249(3):272–280. doi: 10.1007/s004150200004. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 14. Haaz S, Bartlett SJ. Yoga for arthritis: a scoping review. Rheumatic Disease Clinics of North America. 2011;37(1):33–46. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2010.11.001. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 15. Heiwe S, Jacobson SH. Exercise training for adults with chronic kidney disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2011 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003236.pub2.CD003236 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 16. Innes KE, Vincent HK. The influence of yoga-based programs on risk profiles in adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2007;4(4):469–486. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nel103. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 17. Innes KE, Selfe TK, Vishnu A. Mind-body therapies for menopausal symptoms: a systematic review. Maturitas. 2010;66(2):135–149. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2010.01.016. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 18. Kirkwood G, Rampes H, Tuffrey V, Richardson J, Pilkington K. Yoga for anxiety: a systematic review of the research evidence. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2005;39(12):884–891. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2005.018069. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 19. Krisanaprakornkit T, Krisanaprakornkit W, Piyavhatkul N, Laopaiboon M. Meditation therapy for anxiety disorders. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2006;(1) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004998.pub2.CD004998 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 20. Langhorst J, Klose P, Dobos GJ, Bernard K, Häuser W. Efficacy and safety of meditative movement therapies in fibromyalgia syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Rheumatology International. 2012;33(1):193–207. doi: 10.1007/s00296-012-2360-1. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 21. Lee MS, Kim JI, Ha JY, Boddy K, Ernst E. Yoga for menopausal symptoms: a systematic review. Menopause. 2009;16(3):602–608. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e31818ffe39. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 22. Lin KY, Hu YT, Chang KJ, Lin HF, Tsauo JY. Effects of yoga on psychological health, quality of life, and physical health of patients with cancer: a meta-analysis. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2011;2011 doi: 10.1155/2011/659876.659876 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 23. Mahendira D, Towheed TE. Systematic review of non-surgical therapies for osteoarthritis of the hand: an update. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage. 2009;17(10):1263–1268. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2009.04.006. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 24. Marc I, Toureche N, Ernst E, et al. Mind-body interventions during pregnancy for preventing or treating women’s anxiety. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2011;(7) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007559.pub2.CD007559 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 25. Morone NE, Greco CM. Mind-body interventions for chronic pain in older adults: a structured review. Pain Medicine. 2007;8(4):359–375. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2007.00312.x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 26. Muller M, Tsui D, Schnurr R, Biddulph-Deisroth L, Hard J, MacDermid JC. Effectiveness of hand therapy interventions in primary management of carpal tunnel syndrome: a systematic review. Journal of Hand Therapy. 2004;17(2):210–228. doi: 10.1197/j.jht.2004.02.009. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 27. Pilkington K, Kirkwood G, Rampes H, Richardson J. Yoga for depression: the research evidence. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2005;89(1–3):13–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2005.08.013. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 28. Posadzki P, Ernst E, Terry R, Lee MS. Is yoga effective for pain? A systematic review of randomized clinical trials. Complementary Therapies in Medicine. 2012;19(5):281–287. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2011.07.004. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 29. Ram FSF, Holloway EA, Jones PW. Breathing retraining for asthma. Respiratory Medicine. 2003;97(5):501–507. doi: 10.1053/rmed.2002.1472. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 30. Ramaratnam S, Sridharan K. Yoga for epilepsy. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2000;(2) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001524.CD001524 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 31. Slade SC, Keating JL. Unloaded movement facilitation exercise compared to no exercise or alternative therapy on outcomes for people with nonspecific chronic low back pain: a systematic review. Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics. 2007;30(4):301–311. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2007.03.010. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 32. Smith KB, Pukall CF. An evidence-based review of yoga as a complementary intervention for patients with cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 2009;18(5):465–475. doi: 10.1002/pon.1411. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 33. Smith CA, Levett KM, Collins CT, Crowther CA. Relaxation techniques for pain management in labor. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2011 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009514.CD009514 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 34. Alexander GK, Taylor AG, Innes KE, Kulbok P, Selfe TK. Contextualizing the effects of yoga therapy on diabetes management: a review of the social determinants of physical activity. Family and Community Health. 2008;31(3):228–239. doi: 10.1097/01.FCH.0000324480.40459.20. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 35. Beddoe AE, Lee KA. Mind-Body interventions during pregnancy. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing. 2008;37(2):165–175. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2008.00218.x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 36. Brotto LA, Mehak L, Kit C. Yoga and sexual functioning: a review. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy. 2009;35(5):378–390. doi: 10.1080/00926230903065955. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 37. Burgess J, Ekanayake B, Lowe A, Dunt D, Thien F, Dharmage SC. Systematic review of the effectiveness of breathing retraining in asthma management. Expert Review of Respiratory Medicine. 2011;5(6):789–807. doi: 10.1586/ers.11.69. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 38. Innes KE, Bourguignon C, Taylor AG. Risk indices associated with the insulin resistance syndrome, cardiovascular disease, and possible protection with yoga: a systematic review. Journal of the American Board of Family Practice. 2005;18(6):491–519. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.18.6.491. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 39. Kozasa EH, Harumi E, Hachul H, et al. Mind-body interventions for the treatment of insomnia: a review. Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria. 2010;32(4):437–443. doi: 10.1590/s1516-44462010000400018. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 40. Krisanaprakornkit T, Ngamjarus C, Witoonchart C, Piyavhatkul N. Meditation therapies for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2010;6 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006507.pub2.CD006507 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 41. Lynton H, Kligler B, Shiflett S. Yoga in stroke rehabilitation: a systematic review and results of a pilot study. Topics in Stroke Rehabilitation. 2007;14(4):1–8. doi: 10.1310/tsr1404-1. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 42. Mehta P, Sharma M. Yoga as a complementary therapy for clinical depression. Complementary Health Practice Review. 2010;15(3):156–170. [ Google Scholar ]

- 43. Posadzki P, Ernst E. Yoga for asthma? A systematic review of randomized clinical trials. Journal of Asthma. 2011;48(6):632–639. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2011.584358. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 44. Shen YHA, Nahas R. Complementary and alternative medicine for treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. Canadian Family Physician. 2009;55(2):143–148. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 45. Steurer-Stey C, Russi EW, Steurer J. Complementary and alternative medicine in asthma—do they work? A summary and appraisal of published evidence. Swiss Medical Weekly. 2002;132(25-26):338–344. doi: 10.4414/smw.2002.09972. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 46. Towheed TE. Systematic review of therapies for osteoarthritis of the hand. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage. 2005;13(6):455–462. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2005.02.009. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 47. Vickers AJ, Smith C. Analysis of the evidence profile of the effectiveness of complementary therapies in asthma: a qualitative survey and systematic review. Complementary Therapies in Medicine. 1997;5(4):202–209. [ Google Scholar ]

- 48. Oxman AD. Checklists for review articles. British Medical Journal. 1994;309(6955):648–651. doi: 10.1136/bmj.309.6955.648. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 49. Broad WJ. The Science of Yoga: The Myths and the Rewards. New York, NY, USA: Simon & Schuster; 2012. [ Google Scholar ]

- 50. McCall T. Yoga as Medicine. New York, NY, USA: Bantam Dell a Division of Random House; 2007. [ Google Scholar ]

- 51. Guyatt G, GRADE working group Guidelines-best practices using the GRADE framework. 2012, http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/publications/JCE_series.htm .

- 52. Shea BJ, Grimshaw JM, Wells GA, et al. Development of AMSTAR: a measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2007;7, article 10 doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-7-10. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 53. Büssing A, Michalsen A A, Khalsa SBS, Telles S, Sherman KJ. Effects of yoga on mental and physical health: a short summary of reviews. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2012;2012:7 pages. doi: 10.1155/2012/165410.165410 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 54. Côté A, Daneault S. Effect of yoga on patients with cancer: our current understanding. Canadian Family Physician. 2012;58(9):475–479. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 55. Mishra SI, Scherer RW, Snyder C, Geigle PM, Berlanstein DR, Topaloglu O. Exercise interventions on health-related quality of life for people with cancer during active treatment. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2012 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008465.pub2.CD008465 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 56. Stan DL, Collins NM, Olsen MM, Croghan I, Pruthi S. The evolution of mindfulness-based physical interventions in breast cancer survivors. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2012;2012:15 pages. doi: 10.1155/2012/758641.758641 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 57. Holland AE, Hill CJ, Jones AY, McDonald CF. Breathing exercises for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2012 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008250.pub2.CD008250 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 58. D'Silva S, Poscablo C, Habousha R, Kogan M, Kligler B. Mind-body medicine therapies for a range of depression severity: a systematic review. Psychosomatics. 2012;53(5):407–423. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2012.04.006. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 59. Vøllestad J, Nielsen MB, Nielsen GH. Mindfulness and acceptance-based interventions for anxiety disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2012;51(3):239–260. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.2011.02024.x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 60. Moura VL, Faurot KR, Gaylord SA, et al. Mind-body interventions for treatment of phantom limb pain in persons with amputation. American Journal of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2012;91(8):701–714. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0b013e3182466034. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- View on publisher site

- PDF (764.2 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

How does yoga reduce stress? A systematic review of mechanisms of change and guide to future inquiry

Affiliation.

- 1 a Department of Psychology , University of Connecticut , Storrs , CT , USA.

- PMID: 25559560

- DOI: 10.1080/17437199.2014.981778

Yoga is increasingly used in clinical settings for a variety of mental and physical health issues, particularly stress-related illnesses and concerns, and has demonstrated promising efficacy. Yet the ways in which yoga reduces stress remain poorly understood. To examine the empirical evidence regarding the mechanisms through which yoga reduces stress, we conducted a systematic review of the literature, including any yoga intervention that measured stress as a primary dependent variable and tested a mechanism of the relationship with mediation. Our electronic database search yielded 926 abstracts, of which 71 were chosen for further inspection and 5 were selected for the final systematic review. These five studies examined three psychological mechanisms (positive affect, mindfulness and self-compassion) and four biological mechanisms (posterior hypothalamus, interleukin-6, C-reactive protein and cortisol). Positive affect, self-compassion, inhibition of the posterior hypothalamus and salivary cortisol were all shown to mediate the relationship between yoga and stress. It is striking that the literature describing potential mechanisms is growing rapidly, yet only seven mechanisms have been empirically examined; more research is necessary. Also, future research ought to include more rigorous methodology, including sufficient power, study randomisation and appropriate control groups.

Keywords: clinical interventions; methodology; mindfulness; stress reduction; yoga.

Publication types

- Systematic Review

- C-Reactive Protein / analysis

- Hydrocortisone / analysis

- Interleukin-6 / analysis

- Meditation*

- Stress, Psychological / blood

- Stress, Psychological / psychology

- Stress, Psychological / therapy*

- Treatment Outcome

- IL6 protein, human

- Interleukin-6

- C-Reactive Protein

- Hydrocortisone

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- For authors

- Browse by collection

- BMJ Journals More You are viewing from: Google Indexer

You are here

- Volume 11, Issue 12

- Effectiveness and safety of yoga to treat chronic and acute pain: a rapid review of systematic reviews

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- http://orcid.org/0000-0002-2698-9211 Roberta Crevelário de Melo 1 ,

- http://orcid.org/0000-0003-4639-4060 Aline Ângela Victoria Ribeiro 2 ,

- http://orcid.org/0000-0002-5038-6808 Cézar D Luquine Jr 1 ,

- Maritsa Carla de Bortoli 1 ,

- Tereza Setsuko Toma 1 ,

- Jorge Otávio Maia Barreto 3

- 1 Center for Health Technologies SUS/SP, Instituto de Saúde , Secretaria da Saude do Estado de Sao Paulo , Sao Paulo , Brazil

- 2 Institute of Philosophy and Human Sciences , State University of Campinas , Campinas , Brazil

- 3 Fundacao Oswaldo Cruz , Brasília , Brazil

- Correspondence to Dr Jorge Otávio Maia Barreto; jorgeomaia{at}hotmail.com

Background Pain is a sensation of discomfort that affects a large part of the population. Yoga is indicated to treat various health conditions, including chronic and acute pain.

Objective To evaluate the effectiveness and safety of yoga to treat acute or chronic pain in the adult and elderly population.

Study selection A rapid review was carried out, following a protocol established a priori. Searches were carried out in September 2019, in six databases, using PICOS and MeSH (Medical Subject Headings) and DeCS (Descritores em Ciências da Saúde) terms. Systematic reviews were included, and methodological quality was assessed using Assessing the Methodological Quality of Systematic Reviews. The results were presented in a narrative synthesis.

Findings Ten systematic reviews were selected. Two reviews were assessed as of high methodological quality, two as of low quality, and six of critically low quality. Results were favourable to yoga compared with usual daily care, particularly in low back and cervical pain cases. There was little evidence about the superiority of yoga compared with active interventions (exercises, pilates or complementary and complementary medicine). It was also less consistent in pain associated with fibromyalgia, osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, carpal tunnel and irritable bowel syndromes. There was an improvement in the quality of life and mood of the participants, especially for yoga compared with usual care, exercises and waiting list.

Conclusions Overall, the results were favourable to yoga compared with usual care in low back and cervical pain cases. The evidence is insufficient to assert yoga’s benefits for other pain conditions, as well as its superiority over active interventions. The findings must be considered with caution, given their low methodological quality and the small samples in the primary studies reported in the included systematic reviews. Thus, more studies must be carried out to improve the reliability of the results.

- complementary medicine

- public health

- pain management

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information. Not applicable.

This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited, appropriate credit is given, any changes made indicated, and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ .

https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-048536

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

Strengths and limitations of this study

This research followed a validated methodological guideline.

Only the selection done duplicated and independently. The data extraction and quality assessment were performed by one reviewer and verified by another.

No analyses were performed on the overlap of primary studies of the included systematic reviews.

The systematic reviews included had their methodological quality assessed with the Assessing the Methodological Quality of Systematic Reviews tool.

This review report adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses recommendations.

Pain is a major biopsychosocial problem worldwide because it affects the quality of life of individuals and causes considerable economic impact. 1 Pain is a of subjective nature and can be described as an ‘unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with, or resembling that associated with, actual or potential tissue damage’. 2 Although there is still no consensus on the definition of pain, according to the International Association for the Study of Pain it can be classified as either acute (lasts from a few seconds to 30 days) or chronic (more than 3 months to several years). 3–5

In 2017, the USA, Germany, France, Italy, Spain, UK and Japan reported an estimated 119 619 121 cases of acute pain related to surgery, trauma or other disease conditions. 6 In the USA, acute pain was reported by 41 766 061 patients after surgery and by 34 068 366 patients with traumatic injury. Between the European countries studied, Germany and the UK registered the highest number of acute pain cases. 6

Pain is frequent in elderly people. Among residents from long-term care facilities, 49%–83% report that they were regularly in pain. 7 More than 63% of older patients seen in primary healthcare also complain about acute pain. These symptoms were responsible for 69% of the accounted disability in daily routine life activities. 7

A systematic review (SR) showed that low-back pain is the most prevalent, affecting 51%–84% of the general population, followed by cervical pain (15.4%–45.3%). 1 Pain can become a chronic condition that impacts an estimated 10%–55% of the population worldwide. 8–10 Accordingly, pain episodes in Europe, for example, compromise up to 3.0% of gross domestic product, with an annual cost higher than cancer and many heart diseases. 1

In this context, non-pharmacological therapies, such as yoga, have been indicated to manage acute or chronic pain. Yoga is an integrative mind–body practice of oriental origin that involves three main elements: body positions (asana), techniques for controlling and/or regulating breathing (pranayama), and meditation and/or relaxation (samyama). 11 Currently, there are several yoga types, which differ mainly due to variations in the intensity, difficulty and duration of the postures, in addition to variations in the meditation and breathing techniques. ‘Hatha yoga’ and ‘integrative yoga’ are the terms commonly used to refer to several types of yoga practice, including those most used in Western societies, such as Iyengar and Vinyasa yoga or Viniyoga. 11 Such yoga types have been used for many purposes, like physical rehabilitation and comprehensive care for emotionally traumatised individuals. 12

The number of people who practice yoga has been increasing in recent years in Western countries. For example, in the USA, a study reported that approximately 31 million adult Americans have already practised yoga for the prevention of diseases and back pain relief. 13 In Brazil, a survey carried out by the Ministry of Health (MoH) in 2004 showed that 14.6% of the municipalities and states offered yoga at that time, mainly in primary healthcare. 14 Also, yoga was incorporated into the National Policy of Integrative and Complementary Practices in Health, 14 which instituted the offer of traditional and complementary medicines in the Brazilian Unified Health System (SUS). 15 The incorporation of yoga in the SUS is officially justified by possible cognitive, musculoskeletal, endocrine and respiratory benefits. 15 16 For that reason, the number of healthcare providers offering yoga sessions in the SUS increased from 565 in 2017 to 7732 in 2019, as well as the number of patients assisted (from 3870 to 43 459, respectively). 17

Rapid review of SRs carried out by demand of the Brazilian MoH. Rapid reviews are appropriate to provide decision makers with the best available evidence in a short time. 18 A research protocol was previously prepared, describing the eligibility criteria, articles selection, data extraction and methodological quality assessment ( online supplemental file 1 ). This review adhered the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 reporting guidelines. 19

Supplemental material

Eligibility criteria.

The research question was developed following PICOS framework: P=adults and elderly with acute or chronic pain; I=yoga; C=usual treatment, placebo, or no treatment; O=reduction or control of acute or chronic pain and adverse events; S=SRs, with or without meta-analysis. Searches and selection of studies were guided by the following question: What is the effectiveness and safety of yoga practice to treat acute or chronic pain in an adult population, compared with usual treatments, placebo, or no treatment, based on the evidence of SRs?

We searched by SRs of randomised controlled trials (RCT), quasi-RCT, observational studies or qualitative studies, with or without meta-analysis, published in English, Spanish and Portuguese, with no restriction to publication date. Overviews, scoping reviews, integrative reviews, synthesis of evidence for policies, health technology assessment studies, economic assessment studies and primary studies were excluded. Studies that presented pain as a secondary outcome or did not present a clear report on the results were excluded.

Searches were carried out on 27 September 2019, by two researchers, in indexed databases PubMed, Health Systems Evidence (HSE), Epistemonikos, VHL (Virtual Health Library) Regional Portal, Health Evidence (HE) and Embase. The search strategies combined keywords from the PICOS acronym, using MeSH (Medical Subject Headings) terms in Pubmed and DeCS (Descritores em Ciências da Saúde) terms in the VHL, adapting them to HSE, Epistemonikos, HE and Embase. The terms used were: “yoga”, “acute pain”, “chronic pain”, “ioga”, “dolor agudo”, “dolor crónico”, “dor aguda” and “dor crônica”. The SR filter was used in three databases (PubMed, Epistemonikos, VHL Regional Portal) ( online supplemental file 2 ).

Study selection and data extraction

The SRs retrieved were uploaded to Rayyan reference management web application. 20 The screening process followed the steps of excluding duplicates and then reading titles and abstracts. The eligible articles were read in full. Those that did not meet the objectives of this rapid review were excluded. Using an Excel spreadsheet, the following data were extracted from the included studies: authorship, publication year, aims, intervention, comparators, results, limitations, conflicts of interest and last year searched. Both the study selection and data extraction were carried out by two reviewers independently. Conflicts were resolved by a third reviewer.

Quality assessment

Two reviewers independently assessed the methodological quality of studies with the Assessing the Methodological Quality of Systematic Reviews (AMSTAR 2) tool. 21 Assessment disagreements between reviewers were resolved through consensus. To classify the overall confidence in the results of the SRs, the ‘critical domains’ considered were the same suggest by the authors of AMSTAR 2 in their original article: study protocol (item 2); comprehensive search strategy (item 4); list of excluded studies with justification (item 7); adequate technique to assess the risk of bias in each study included in the review (item 9); appropriate methods for meta-analysis (item 11); risk of bias in each study when interpreting the results (item 13); and publication bias (item 15). Cohen’s kappa statistic was calculated to estimate each domain’s inter-rater reliability (IRR).

Synthesis of results

Results were analysed based on the effect size measures informed by the SRs (MD: means difference; RR: risk ratio; SMD: standardised means difference; 95% CI; I 2 : heterogeneity measure). A narrative synthesis of the results was prepared for each outcome about benefits and adverse events.

Patient and public involvement

No patients or public participated in any stage of this review. Results were presented to decision makers.

The PRISMA flow diagram shows the selection process ( figure 1 ). Searches yielded 693 references, of which 250 remained for screening of titles and abstracts after duplicates were removed. Records were excluded after screening because they were a duplicate (4.8% out of 250), full-text not available (1,2%) or for not meeting at least one of the eligibility criteria: outcome (40.4%), not an SR (27.6%), population (14%) or intervention (2,8%). Twenty-three reviews were read in full to check eligibility and 13 were excluded for the following reasons: not an SR, 22–29 not an yoga intervention 30–33 or necessary data unavailable for extraction. 34 Thus 10 SRs were included, 12 35–43 eight with meta-analysis ( online supplemental file 3 ).

- Download figure

- Open in new tab

- Download powerpoint

Study selection flow diagram, adapted from Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses. 19

Studies characteristics

Primary studies included in the SRs were conducted in the USA (5), 35–39 India (4), 36–39 Sweden (3), 35 38 39 Germany (2), 36 39 China (2), 38 39 Korea (2), 38 39 England (2), 37 38 Brazil (2), 35 38 Spain (1) 35 and Turkey (1). 39 Five reviews did not present this information. 12 40–43

The studies included in the reviews analysed different types of yoga, the most frequent ones being yoga iyengar, 12 37 38 40 42 43 hatha yoga 37–39 42 43 and viniyoga, 37 38 40–43 yogic mind resonance technique, 39 yoga of awareness, 35 43 yoga‐based special techniques 37 yogic meditation 37 and two reviews did not specify a yoga type used. 12 40

Yoga was combined with home practice, 35–38 41–43 daily mostly, educational resources (booklets, guides, newsletters) about yoga 37 38 41–43 or pain, 37 CDs (Compact Disc) or DVDs (Digital Versatile Disc), 35 38 42 43 physiotherapy, 36 39 relaxation, 35 40 education, 40 occupational therapy sessions 37 and usual care. 37 38 41 42

The person responsible for the practice was mentioned to be an experienced yoga teacher, 36 37 42 43 but this information was not available for the majority of SRs included. 12 35 36 39–41

The duration of sessions ranged from 15 min 41 to 3 hours 12 and frequency varied from one 12 to seven times 43 per week. The follow-up of participants continued for the minimum of 1 42 and maximum of 24 38 weeks.

Comparisons were made to usual care, 12 35–37 40 42 educational interventions, 12 37 38 41–43 standard medical care 42 ; exercises, 12 37–39 41 and delayed treatment. 35 Yoga interventions were also compared with waiting list controls, mostly unspecified, 12 37 40 43 but in one case there was a subsequent offer of intervention or treatment at some point or at the end of the study. 38 Other integrative practices such as Tai-chi or pilates 39 or no intervention 12 40 were compared as well.

SRs described results on the following outcomes: pain, functional capacity, psychosocial outcomes, quality of life, specific back deficiency, overall clinical improvement and adverse events. The effectiveness of yoga was assessed in reducing low-back pain 12 38 41 42 ; cervical pain 36 39 ; pain associated with fibromyalgia 35 ; pain associated with irritable bowel syndrome 12 ; pain associated with carpal tunnel syndrome 12 ; pain caused by musculoskeletal conditions 43 ; and chronic non-malignant pain. 40

Pain after yoga was measured using the following scales and questionnaires: Visual Analogue Scale 12 35–40 42 43 ; Numeric Rating Scale 12 38 39 42 43 ; Aberdeen Back Pain Scale 12 37 38 42 ; McGill Pain Questionnaire and variations 12 38 39 42 ; Pain Bothersomeness Scales 12 42 43 ; Pain Analogue Scale 36 ; Pain Diary 12 ; Joint tenderness and hand pain during activity 40 ; Brief Pain Inventory 38 ; Pain Disability Index 38 ; Simple Descriptive Pain Intensity Scale 43 ; Neck Pain and Disability Scale 39 ; Neck pain-related disability 36 ; Oswetry disability index pain 12 37 ; Northwick Park Questionnaire 39 ; Pain and Disability Chronic Pain Grade Scale 39 ; Pressure Pain Threshold 39 ; Pain and physical function Western Ontario and McMaster Universities 40 ; Symptom bothersomeness. 40

Two SRs were of high methodological quality, 37 38 two were assessed as low quality, 35 42 and six of critically low quality. 12 36 39–41 43 Overall IRR before consensus was estimated from an average of Cohen’s kappa (κ) through AMSTAR 2 domains (mean κ=0.59). Figure 2 details the assessment of each AMSTAR 2 item.

Summary of quality using Assessing the Methodological Quality of Systematic Reviews.