Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Download Free PDF

The History of Art in Japan

The leading authority on Japanese art history tells the story of how the country has nurtured unique aesthetics, prominent artists, and distinctive movements. Nobuo Tsuji sheds light on works ranging from the Jomon period to contemporary art, from earthenware figurines in 13,000 B.C. to manga and modern subcultures.

Related papers

Japan Forum, 2024

Journal of Asian Studies, 2018

The Legacy of Japanese Artistic Influence on Art Nouveau - The Tides of Change, 2021

In order to appreciate the continental, cultural and stylistic interrelationships between Japanese, European and North American, I would that I had to go back in history to fully understand how porcelains and related artworks, especially Chinese, Japanese and then British and continental European, influenced each other. It was much more difficult to fully comprehend the transition of Japanese artworks in the western style through Art Nouveau and into Art Deco than I would have imagined.

Journal of Fine Arts, 2001

This paper is a short, methodologically limited excursion into investigating what is a large question, not without practical importance for Australia and its art world: the structure of Japanese perceptions of and relations with 'modern Asian art'. Published in 2014: ‘Japan and Modern Asian Art’, Journal of Fine Arts [Bangkok: Silpakorn University] vol. 1 no. 2, 49-78.

EARLY MODERN JAPAN, 2002

This article and accompanying bibliography surveys the state of the field of Early Modern Japanese art studies through the date of the publication (2002) in Western languages (primarily in English).

This is an alternate version of the bibliography published in the journal EARLY MODERN JAPAN (fall 2002), arranged chronologically within categories.

This is a continuation of my paper on the influence/influencing of Japanese arts associated with Japanism, Arts and Crafts and most importantly Art Nouveau

International Journal of Comic Art, 2014

Ishinomori Shōtarō (石ノ森 章太郎) provided the blueprint for the rewriting of history in Japanese graphic art. In Japan the hyperbole of his name ‘forest of stone’ is also synonymous with a plethora of other superlatives. Ishinomori not only wrote the prototype for the first gakushū (学習) manga on economics , defined a new graphic genre in the process and thus paved the way for ‘serious’ manga to enter the educational discourse in Japan, but also holds the Guinness Book World Record for the most pages drawn by a single artist; totaling more than 128,000 pages. As if this was not enough, Ishinomori raised the bar by almost single-handedly penning the first comprehensive history of the Japanese Archipelago in his magnum opus Manga Nihon no Rekishi (マンガ日本の歴史; Manga A History of Japan). This voluminous compendium marks an attempt at historiographical analysis of Japanese history from its ancient ancestral roots right up to the contemporary world. Despite the transcultural renaissance of manga on a global scale the neglect of his work from the discourse of Japanese cultural representation is somewhat surprising. Whereas books on the likes of Tezuka Osamu and the lesser known but still influential Yoshihiro Tatsumi have been highly appraised recently, Ishinomori, - usually labelled as a science fiction manga artist - as one of the founding fathers of the modern manga media is hardly discussed in the Western press. With this contradiction in mind this paper will evaluate the position of Ishinomori’s graphic analects of Japan in comparison to several other archetypes of graphic histories such as Yokoyama Mitsuteru’s Sangokushi (Romance of the Three Kingdoms, 1971-1986), Tezuka Osamu’s Hi no tori (Phoenix, 1978-1995) and Mizuki Shigeru’s Comikku Showa-Shi (Hereafter: Comic History of Shōwa, 1988-1989). The paper will demonstrate how Ishinomori’s representation of Japanese history in manga constitutes a new form of literacy that enables the visualisation of historical artefacts in relation to contentious issues of Japanese identity and memory formation.

The Journal of Art Historiography, 2014

In 1999 I organised a two-day conference, 'The Two Art Histories: The Museum and the University,' held at the Clark Art Institute in Williamstown, Massachusetts. The published papers, which appeared in book form in 2002, generated considerable interest, particularly among museum curators, and spawned further discussions of the topic at several conferences. One of these was a half-day symposium held in October 2005 at the Institute of Art and De- sign, University of Tsukuba, in Japan, to which I was invited to speak, along with art histo- riansfrom Japan and South Korea. The paper I presented there was published in the conference proceedings, but has found little distribution outside of Japan.1 Because the topic continues to be relevant, Richard Woodfield kindly proposed that I publish it here so that it might reach a wider readership. - CWHBefore I begin I wish to thank the Institute of Art and Design at the University of Tsukuba for its generous invitation to participate in...

La Razon, 2023

International Journal of Communication, vol. 18, 2024

https://www.hikmetsahiner.com, 2023

Papers de recerca històrica, 11, 2023

Atalanta. Revista de la Letras Barrrocas, 2024

Communications, 1987

La Rivista di Etnografia, 1971

MRS Proceedings, 1996

BMJ Open, 2014

PM&R, 2014

The Journal of Chemical Physics, 2010

Biomolecules, 2020

International Symposium on Display Holography Proceedings , 2023

Applied Physics Letters, 2006

Canadian Journal of Civil Engineering, 2021

Communications in Computer and Information Science, 2017

Related topics

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

A beginner’s guide to the art of Japan

Gain an birds-eye view of the arts of Japan.

prehistory - present

A brief history of the arts of Japan: the Jomon to Heian periods

By Dr. Sonia Coman

Learn about Japan's famous haniwa, tales from behind palace walls, and enormous wooden buddhas.

A brief history of the arts of Japan: the Kamakura to Azuchi-Momoyama periods

Learn about tea-ceremonies, opulent palaces, and splashed-ink paintings from Japan's Kamakura to Azuchi-Momoyama periods.

A brief history of the arts of Japan: the Edo period

Learn about floating worlds and the art of the literati from Japan's Edo period.

A brief history of the arts of Japan: the Meiji to Reiwa periods

Learn about Japan's modern cityscapes, art in a time of peace, and the dawn of a new era.

Japanese art: the formats of two-dimensional works

By The British Museum

From printed books and fan paintings to screens and sliding doors, two-dimensional art took many forms in Japan.

Your donations help make art history free and accessible to everyone!

52 Japanese Art Essay Topic Ideas & Examples

🏆 best japanese art topic ideas & essay examples, 🎓 good research topics about japanese art, 🥇 interesting topics to write about japanese art.

- The Complexity of Traditional Chinese and Japanese Theater Arts Comedic plays gained popularity since the start of the theater in 1603, but public outrage over the vulgarity and excess eroticism of kabuki led to the government prohibiting women from acting in the plays.

- Japanese Shrines Architecture Uniqueness They also concentrated much on the visual elegance and the actual balance of the building compared to the level of the environment.

- V. Horta’s Tassel Hotel and the Pavilion for Japanese Art by B. Goff The Art Nouveau works of art are characterized by the use of the new materials and technologies from one side and the motives of the ancient myths and spiritual world on the other.

- Mono-Ha. Japanese Art Style. Concepts and Impact on Cultural Trends These movements and styles developed as a result of a special vision of the world common for Japanese people who are known for their devotion and tender affection to nature and its beauty, and the […]

- Effects of Globalization in the Contemporary Japanese Art They have in turn influenced the art of painting in Japan to develop it and push it to a global level.

- Japanese Painters: Asai Chu and Hashimoto Hashimoto Sadhide a renowned Japanese painter born in 1807 and he died in 1878; the painter lived in the city of Yokohama which was known to be a western settlement.

- The Influence of Japanese Art Upon Mary Cassatt Critics admit that Japanese motifs are evident in her works especially in her entire work, devoted to the representation of woman and the child, which is a kind of revenge for repressed maternity: unmarried, she […]

- Traditional Japanese Architecture One of the major causes of the abovementioned twists has been the commencement of Buddhism in the country, which was greatly influenced by the socialism from China.”Beasley believes that “by the eleventh century the Chinese […]

- Women in Art: Yayoi Kusama, Maya Lin, Zaha Hadid In her autobiography, Kusama says that “deep in the mountains of Nagano,” where she was born in 1929, she had discovered her style of expression: “ink paintings featuring accumulations of tiny dots and pen drawings […]

- Yayoi Kusama’s Art and Oriental Way of Life Such a point of view is, of course, is fully legitimate – especially given the unconventional aesthetic subtleties of Kusama’s artistic installations, the long history of psychosis, on the author’s part, and the fact that […]

- Kimono Art in Traditional Japanese Clothing The Kimonos were introduced in the Japanese culture during the Heian period. The government of the time agitated for westernization, where the Japanese people were to adopt western culture including the western attire.

- Ancient Egyptian and Japanese Art: Comparative Analysis

- Art Criticism Using the Frames – Chinese and Japanese Art

- Ancient Japanese Art Artists Hiding Place

- Comparative Analysis of Chinese and Japanese Art

- Exploring the Unique Japanese Art

- Impressionist Artists and the Influence of Japanese Art

- Overview and Analysis of Japanese Art and Culture

- Japanese Art During the Asuka Period

- Kabuki, the Japanese Art vs. Puccini’s Madame Butterfly: Comparison

- Japanese Art Infused Into the Temple of Todaiji

- Overview and Analysis of Modern Japanese Art

- Japanese Art: Shinto vs. Buddhism

- Origami: The Japanese Art of Paper Folding

- Japanese Art: World War II and American Occupation

- The Great 19th Century Impressionists Influenced by Japanese Art

- Urawaza: The Japanese Art of Lifehacking

- The Effect of Culture and Mythology on Japanese Art

- Japanese Manga as an Art Form

- A Study of the Origin of Judo and Jujutsu, a Japanese Art

- An Overview of the Beauty Principle in Japanese Art

- The Most Collected and Popular Kind of Art, the Japanese Art

- The History of Japanese Art Before 1333

- Japanese Art: The Edo Period of the Japanese Culture

- Analysis of Western Influence on Japanese Art

- How Japanese Art Influenced Their Works of Art

- Effects of Japanese Art on French Art in the Late 19th Century

- The Link Between Japanese Art and Shintoism

- How Japanese Art Influenced Van Gogh’s Paintings

- Comparison of Non-western Art vs. Japanese Art

- Overview of the Japanese Art of Ukiyo-e

- Literature, Art, Sport, and Cuisine of Japanese Culture

- Contemporary Japanese Art: Between Globalization and Localization

- The Impact of the First World War on Japanese Art

- Japanese Art: The History of Pottery

- John la Farge’s Discovery of Japanese Art

- Japanese Art: History, Characteristics, and Facts

- Looking at the Most Famous Japanese Artists and Artworks

- From Japonisme to Japanese Art History: Promoting Japanese Art in Europe

- Overview of Major Themes in Japanese Art

- The Chinese Influence on Japanese Art

- Vincent van Gogh Research Ideas

- Contemporary Art Questions

- Fashion Design Topics

- Mayan Research Ideas

- Tea Research Topics

- Baroque Essay Topics

- Yoga Questions

- Invasive Species Titles

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2022, September 4). 52 Japanese Art Essay Topic Ideas & Examples. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/japanese-art-essay-topics/

"52 Japanese Art Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." IvyPanda , 4 Sept. 2022, ivypanda.com/essays/topic/japanese-art-essay-topics/.

IvyPanda . (2022) '52 Japanese Art Essay Topic Ideas & Examples'. 4 September.

IvyPanda . 2022. "52 Japanese Art Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." September 4, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/japanese-art-essay-topics/.

1. IvyPanda . "52 Japanese Art Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." September 4, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/japanese-art-essay-topics/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "52 Japanese Art Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." September 4, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/japanese-art-essay-topics/.

IvyPanda uses cookies and similar technologies to enhance your experience, enabling functionalities such as:

- Basic site functions

- Ensuring secure, safe transactions

- Secure account login

- Remembering account, browser, and regional preferences

- Remembering privacy and security settings

- Analyzing site traffic and usage

- Personalized search, content, and recommendations

- Displaying relevant, targeted ads on and off IvyPanda

Please refer to IvyPanda's Cookies Policy and Privacy Policy for detailed information.

Certain technologies we use are essential for critical functions such as security and site integrity, account authentication, security and privacy preferences, internal site usage and maintenance data, and ensuring the site operates correctly for browsing and transactions.

Cookies and similar technologies are used to enhance your experience by:

- Remembering general and regional preferences

- Personalizing content, search, recommendations, and offers

Some functions, such as personalized recommendations, account preferences, or localization, may not work correctly without these technologies. For more details, please refer to IvyPanda's Cookies Policy .

To enable personalized advertising (such as interest-based ads), we may share your data with our marketing and advertising partners using cookies and other technologies. These partners may have their own information collected about you. Turning off the personalized advertising setting won't stop you from seeing IvyPanda ads, but it may make the ads you see less relevant or more repetitive.

Personalized advertising may be considered a "sale" or "sharing" of the information under California and other state privacy laws, and you may have the right to opt out. Turning off personalized advertising allows you to exercise your right to opt out. Learn more in IvyPanda's Cookies Policy and Privacy Policy .

Upheaval and Experimental Change:

Japanese art from 1945 to the end of the 1970s, by hajime nariai curator, tokyo station gallery and adjunct professor at joshibi university of art and design, tokyo.

In the summer of 2015, the phrase “the 70th year of the postwar era” appeared in all the Japanese newspapers. I wonder if there are any other nations that have been burdened with the term “postwar” for such a long time, in our case continuously since the end of World War II. According to Eiji Oguma, one of Japan’s most noted sociologists, “postwar” is not a term of periodization rather its meaning, in Japan, is equivalent to “nation-building.” Indeed, the summer of 1945 saw the national structure of our country redesigned from the ground up.

It could be said that the first thirty years of “the history of Japanese postwar art,” which I will quickly survey in this essay, is a trajectory of very fresh artistic activities in a newly born (or re-born) country. During this period, Japan raced along at a high speed, beginning from a jump-start to a fast acceleration and then proceeding at a steady rate. The 1950s witnessed a new society arise from vast areas of scorched ground, the 1960s an era when Japan become an economic power through its incredible growth, and, in the 1970s, a maturation period, with the arrival of a fully developed consumer and information-based society.

Along with this, Japan’s art underwent drastic changes and shifts. Emerging from the deeply engraved mark of 1945 as the beginning of the “contemporary”, artworks made during this period possess an enduring rawness and vitality, making them feel contemporary even today, decades after their creation.

In the first half of the “postwar” period, Japanese artistic practice grew with drastic changes, winding through new styles and bold gestures of experimentation. As a body undergoing intense growth spurts in a short period of time, these initial decades were characterized by unexpected twists and strains, aimed at destabilizing many previous and established conventions of art making and Japanese aesthetics. Japanese society, and its artists, grappled with the conflicting experiences of liberation from the Imperial and intensely nationalistic governance and, at the same time, intense reactions towards Americanization and the occupation that characterized these initial decades after the war ended. What is surprising is that the identity of Japanese contemporary art remains elusive and shaky, despite these seminal forerunners’ pursuits. At present, we in Japan are still formalizing a fully authorized Japanese postwar art history and confronting our own contemporary art.

1945 to the 1950s: Wound or Reset

Sur-documentalism and avant-garde.

After the Allied occupation from 1945, Japan finally recovered its sovereignty through the San Francisco Peace Treaty in 1952. Two main types of artists pioneered new directions in this highly-charged period: those who viewed Japan s defeat as a wound and those who approached it as a reset.

Sur-documentalism, advocated by the writer and critic Kiyoteru Hanada as a new type of realism, applied aesthetics associated with Surrealism to paintings, shedding light on social injustices and revealing deeper layers of reality. Also known as its alias, “Reportage Paintings”, works by artists of this movement (Tatsuo Ikeda, Kikuji Yamashita, etc.) portrayed oppressed people and controversial incidents as caricature, based on their first-hand investigation of the dark sides of society.

In contrast, the avant-garde artists initiated artistic innovation through their unconventional methodologies. As inheritors of the pre-war generation of avant-garde painters, such as Yoshishige Saito and Takeo Yamaguchi who established the group Kyushitsukai (Ninth Room Association), these artists would form the mainstream of the early postwar Japanese art history; the groups Jikken Kobo (Experimental Workshop) in Tokyo and Gutai in Osaka. Formed around the critic Shuzo Takiguchi in 1951, Jikken Kobo was composed of members who were as curious as laboratory workers about experimentation, engaging in cutting-edge, all-encompassing, works of art, by incorporating industrial technologies, music, theater and different media. Gutai, formed in 1954, was different.

Responding to the proposition, “Do what no one has ever done before,” the favored dictum of its leader and chief proponent, Jiro Yoshihara, Gutai s members invented radical ways of art making, such as painting with feet (Kazuo Shiraga) or calling an electric circuit a painting (Atsuko Tanaka). Yoshihara himself had been a member of Kyushitsukai (Ninth Room Association) and also made Surrealistic paintings and calligraphically-based abstractions. Inviting the formless such as bodily actions and fluid materials to the notion of painting, Gutai works were described by Allan Kaprow as a precursor of Happenings, and positioned by Michel Tapi as a representative of Art Informel. It is possible to view Gutai paintings as works emancipated from all restraints associated with modern art, and with a kinship to their contemporaries such as Jackson Pollock and Robert Rauschenberg.

I wonder if there are any other nations that have been burdened with the term “postwar” for such a long time.

1960s: Art Informel Sensation and Revelry

The escalation of anti-art.

Art Informel, a French term describing various styles of abstract painting that were gestural during the 1940s and 1950s, was associated with Gutai and possessed strong ties with Japan. Prior to the founding of Gutai, Japanese painters including Toshimitsu Ima , Hisao Domoto and Kumi Sugai, were already associated with this movement in France and its creative resonance, as well as its break from tradition in modernism, was distinctively felt in Japan.

Introduced into Japan in the late 1950s, Art Informel advocated the materiality of paints and the act of painting itself and instigated the production of anarchistic works oozing intense emotions amongst the younger artists. The Yomiuri Independent, an annual, unjuried and non-competitive exhibition, became their platform, filled with odd, almost garbage-like works combined with movement and sound, often made of discarded everyday items and obsolete materials. Continuing until 1963, this annual exhibition produced many young stars, such as Ushio Shinohara, Tetsumi Kudo and Hi-Red Center, and ended when the self-destructive craze by radical artists, so-called “Anti-Art,” reached its peak in the early 1960s.

Anti-Art emerged as part of the globally erupting counterculture. Not only art, but also culture in general in Japan, saw an explosion of often brutal, savage or wild body performances as well as archaic and more traditional visuals. It was resistance against modernity, propelled by the complication of people’s mixed feelings: they loved and hated the postwar modernization, because what it actually meant to them was nothing short of full scale Americanization. Cultural icons of this period include Tatsumi Hijikata’s Butoh dance focusing on the Japanese body, Juro Kara’s and Shuji Terayama’s Angura (Underground) Theatre and the signature blurry photographs (are, bure, boke) by Daido Moriyama and Takuma Nakahara, as well as kitsch posters by Tadanori Yokoo. Even as the basic attitude of the artists was “anti-establishment,” this radical and festive mood was also intrinsically bound up with Japan’s elation, buoyed up by two enormous national events: the 1964 Summer Olympics (Tokyo) and Expo ’70 (Osaka).

1970s: The Calm after the Storm

The triumph of mono-ha.

After the revelry comes repose. The hot resistance, which characterized the 1960s, gradually shifted to cool-headed questionings. After each and every existing institution and value related to art was challenged, the next target set upon was the artist s intention. From this came a style of not making, later called Mono-ha. Artists who emerged in the late 1960s, such as Lee Ufan, who placed rocks on broken glass, and Kishio Suga, who, in a matter-of-fact way, leaned square pieces of timber against architecture, employed minimal materials and actions to explore primordial relationships with the world.

With Lee Ufan, well informed by both Eastern and Western philosophies, as its theoretical pillar, Mono-ha was not a group but a tendency of loosely interconnected artists, unintentionally coinciding with the contemporary ascetic practices such as Minimalism and Arte Povera. The ambiguity of the Japanese term mono, which covers various concepts such as objects, materials, things, and even situations, indicates their specific orientation. Staying away from articulate symbolization and objectification of the world, namely anthropocentrism, the Mono-Ha artists attempted to touch the intrinsic mystery of the world with no distinctions between objects and situations. Moreover, their practice of not making was interrelated with a new stream of conceptualism, in which works made solely of words emerged one after another, from artists like Jiro Takamatsu and Yutaka Matsuzawa. In stark contrast to the 1960s, art in the 1970s was nourished by such a style of rational contemplation.

At the same time, works using reproducible media blossomed, not only in the field of visual art but also in other genres such as anime, manga, illustration and graphic design, fueled by the growth of accessible technology such as video and in popular culture with the widespread availability of the TV and magazines. Such cultural activities, centered around consumer industries, functioned as an incubator for the genealogy of art after the 80s, in which glamour and flamboyance would be regained.

- Resources for COVID-19

- Graduate Student Info

- Member Login

CHINO KAORI MEMORIAL PRIZE

The Japan Art History Forum’s Chino Kaori Memorial Essay Prize recognizes outstanding graduate student scholarship in Japanese art history. The prize was established in 2003 in memory of our distinguished colleague Chino Kaori, and is awarded annually to the best research paper written in English on a Japanese art history topic.

The prize winner will receive a complimentary two-year membership to JAHF.

See below for submission instructions.

Past Winners

2024 Mia Kivel The Ohio State University “The Jōmon Imaginary in Postwar Japanese Art.”

2023 Lillian T. Wies University of Maryland, College Park “Marked: Shima Seien and the Curse of a ‘Female Artist’”

2023 Mew Lingjun Jiang University of Oregon “Pride of the Self and Prejudice Against the Other: Daylight Fireworks in Nineteenth-Century Japanese Woodblock Prints”

2022 Eve Loh Kazuhara National University of Singapore “Tanaka Isson’s Landscapes of Isolation and Wilderness from Amami Oshima”

2021 Trevor Menders Harvard University “Painter in the City: Placing Shimomura Kanzan”

2020 Mai Yamaguchi Princeton University “Hold the Brush: Reprinting and Adapting Chinese Painting Manuals in Nineteenth-Century Japan”

2019 Suhyun Choi University of British Columbia “Dressing Difference: Representations of Chima Chogori in Japan and an Ethics of Subjectivity”

2018 Kelly McCormick University of California Los Angeles “The Cameraman in a Skirt: Tokiwa Toyoko, the Camera Boom, and the Nude Shooting Session”

2017 Carrie Cushman Columbia University “Temporary Ruins, Recurring Memories: Miyamoto Ryuji’s Architectural Apocalypse (1988)”

2016 Elizabeth Self University of Pittsburgh “A Mausoleum Fit for a Shogun’s Wife: the Two Seventeenth-Century Mausolea for Sugen-in”

2015 Yurika Wakamatsu Harvard University Feminizing Art in Modern Japan: Noguchi Shohin (1847-1917) and the Changing Conceptions of Art and Womanhood “

2014 Eugenia Bogdanova-Kummer Heidelberg University “The Material Is The Message: Rubbings and Prints in Postwar Japanese Calligraphy”

2012 Sara Sumpter University of Pittsburgh “Visualizing the Invisible: Supernatural Sight and Power in Early-Medieval Japanese Handscrolls”

2011 Jeannie Kenmotsu University of Pennsylvania “Sites and Sights of Pleasure in the Eastern Capital: Poetry, Place, and Patronage in Suzuki Harunobu’s Zashiki hakkei and Furyu zashiki hakkei”

2010 Christina M. Spiker University of California, Irvine “Creating an Origin, Preserving a Past: Arnold Genthe’s 1908 Ainu Photography”

2009 Hyunjung Cho University of Southern California “Building the Narrative of Postwar Japan: Tange Kenzo’s Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park”

2008 Namiko Kunimoto UC Berkeley “Electric Dress and the Circuits of Subjectivity”

2007 Ryan Holmberg Yale University “It was not so easy to be born: Hayashi Seiichi manga”

2006 Jung-Ah Woo UCLA “The End of Eternity: Yoko Ono and Art after the War”

2005 Maki Kaneko University of East Anglia “Art and the State: Government-Sponsored Art Exhibitions and Art Politics in Wartime Japan”

2004 Alicia Volk Yale University “When the Japanese Print Became Avant-garde: Yorozu Tetsugoro and Taisho period Creative Prints”

2003 John Szostak University of Washington “Hada Teruo: An Exploration of the Life and Practice of a Modernist Buddhist Painter”

Submission Instructions

The competition is open to graduate students from any university. Recent graduates are also eligible to apply, up to one year from their date of graduation.

Essays may not be previously published in any form or currently under review for publication.

Submissions should include an essay, abstract, and illustrations that conform to the following guidelines:

Essay: under 10,000 words (13,000 including notes), in 12 pt., double-spaced font.

Abstract: 250 words.

Illustrations: size of the total file must be under 10MB.

Please send the above three items in a single Word or PDF file to [email protected]

Submissions open on April 15. The annual deadline for submissions is July 15.

Please direct any questions to jahf secretary, [email protected].

The Society for Japanese Art (SJA) provides an inspiring platform for sharing knowledge and experience regarding every aspect of the visual and applied arts of Japan.

The Plum Blossom Valley at Tsukigase

Rare Appearances: Bunraku Puppets in Osaka Prints

Interpretations of Late Edo Prints on the Theme of Oiwa

News on Japanese Art

Exhibitions and Publications: Autumn 2024

The society's seasonal selection of exhibitions and publications on Japanese art.

Auction: Japanese prints from the personal collection of René Scholten

Cabinet Portier & Associés, in association with Audap & associés, is pleased to announce the sale of Japanese prints f

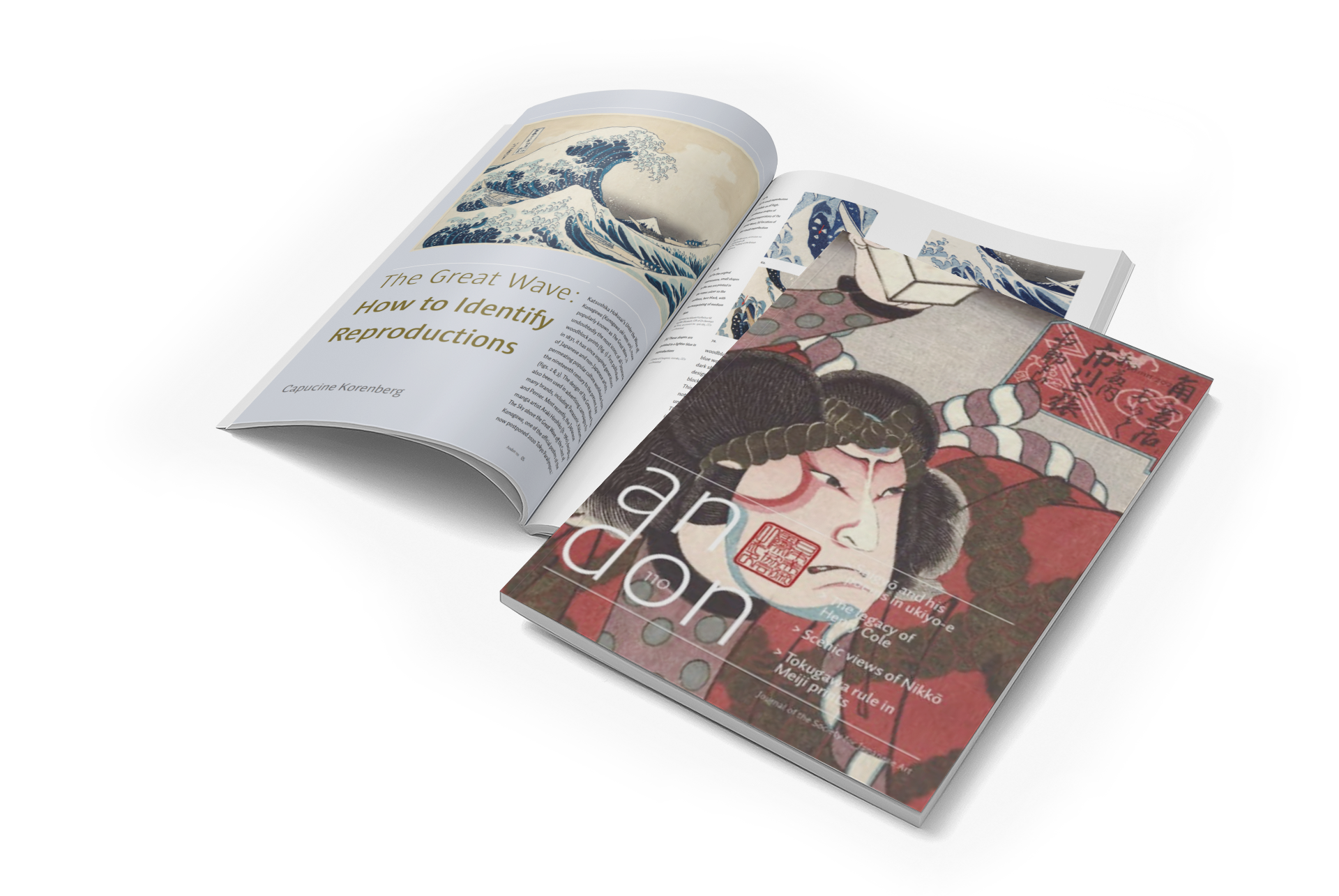

Andon Magazine

Andon (Japanese for ‘lantern’) sheds light on Japanese Art. Andon is published twice a year by the Society for Japanese Art and packed with lavishly illustrated research papers and essays.

Inside of Andon

Become a SJA member

Individual or institute*.

2 x Andon per year

Access to the online Andon Collection

Access to SJA activities and news

Access to a world wide network

€75 / €85 per year

Partner membership*

€25 per year

Student membership*

€40 per year

Lecture: Japanese Printmaking by Ayomi Yoshida

Sponsors of the society.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Japanese art is the painting, calligraphy, architecture, pottery, sculpture, and other visual arts produced in Japan from about 10,000 BCE to the present. Within its diverse body of expression, certain characteristic elements seem to be recurrent: adaptation of other cultures, respect for nature as a model, humanization of religious iconography ...

In Japan’s self-imposed isolation, traditions of the past were revived and refined, and ultimately parodied and transformed in the flourishing urban societies of Kyoto and Edo.

After Japanese ports reopened to trade with the West in 1853, a tidal wave of foreign imports flooded European shores. On the crest of that wave were woodcut prints by masters of the ukiyo-e school, which transformed Impressionist and Post-Impressionist art by demonstrating that simple, transitory, everyday subjects from "the floating world" could be presented in appealingly decorative ways.

The Kano school was the longest lived and most influential school of painting in Japanese history; its more than 300-year prominence is unique in world art history. Jump to content tickets Member | Make a donation. Search. ... Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 1988. Additional Essays by Department of Asian Art.

Often referred to as Japan's "early modern" era, the long-lived Edo period is divided in multiple sub-periods, the first of which are the Kan'ei and Genroku eras, spanning the period from the 1620s to the early 1700s. Kanō Tan'yū, Landscape in Moonlight, after 1662, one of three hanging scrolls, ink on silk, 100.6 x 42.5 cm.

Chapter 45. The four seasons in the arts of Japan. Nature has been a source of inspiration and subject matter in the arts of Japan throughout the centuries. by Dr. Sonia Coman. Sesson Shukei, Landscape of the Four Seasons, c. 1560, six-panel screen (one of a pair); ink and light colors on paper, 156.5 cm × 337 cm (Art Institute of Chicago ...

RESOURCES BOOK REVIEW ESSAY The History of Art in Japan By Nobuo Tsuji and (trans.) Nicole Coolidge Rousmaniere New York: Columbia University Press, 2019 664 pages, ISBN: 978-0231193412, Paperback Reviewed by Brenda G. Jordan N obuo Tsuji's History of Art in Japan was originally published by the University of Tokyo Press in 2005 and is now available in English translation.

A brief history of the arts of Japan: the Kamakura to Azuchi-Momoyama periods. By Dr. Sonia Coman. Learn about tea-ceremonies, opulent palaces, and splashed-ink paintings from Japan's Kamakura to Azuchi-Momoyama periods. Learn more.

Ukiyo-e, or "pictures of the floating world," represents a significant artistic movement originating during Japan's Edo period. Characterized by its woodblock prints, ukiyo-e art depicted everyday life, landscapes, and the beauty of nature. The style of ukiyo-e has notably inspired many Western artists in the 19th century, including the ...

Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History Essays Woodblock Prints in the Ukiyo-e Style. Xu You and Chao Fu Okumura Masanobu ... History of Japanese Art. Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2004. Merritt, Helen. Modern Japanese Woodblock Prints: The Early Years. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1990.

Japanese Art. Japan has a rich history of art that goes back thousands of years. Some ancient Japanese art is thought to have originated in about 10,000 BCE. Traditional Japanese art includes ...

Japanese Kimono: A Part of Cultural Heritage. The other reason behind the waning popularity of the kimono is the intricate design used in its knitting. In the beginning of the 18th century, the name of this garment was changed to kimono. We will write a custom essay specifically for you by our professional experts.

Japanese Culture: Art, history and society. The Japanese culture is one that is rich within an historical and traditional context. Many of the traditional practices established hundreds of years ago can be seen today in modern Japan and are a direct reflection of significant historical accounts. The role of woodblock art in Japanese culture is ...

Along with this, Japan's art underwent drastic changes and shifts. Emerging from the deeply engraved mark of 1945 as the beginning of the "contemporary", artworks made during this period possess an enduring rawness and vitality, making them feel contemporary even today, decades after their creation. In the first half of the "postwar ...

The Japan Art History Forum's Chino Kaori Memorial Essay Prize recognizes outstanding graduate student scholarship in Japanese art history. The prize was established in 2003 in memory of our distinguished colleague Chino Kaori, and is awarded annually to the best research paper written in English on a Japanese art history topic.

1027 Words. 5 Pages. 3 Works Cited. Open Document. Throughout many centuries, art has portrayed an exceedingly dominant role in Japanese culture. These forms of artwork varied from everything from pottery to clay figurines. Overall, the majority of Japanese art was and still is considered to be of high importance in Japanese history.

History of Japanese Art. Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2004. Murase, Miyeko. Bridge of Dreams: The Mary Griggs Burke Collection of Japanese Art. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000. See on MetPublications. ... Additional Essays by Department of Asian Art.

The Met's Timeline of Art History pairs essays and works of art with chronologies and tells the story of art and global culture through the collection. ... Seasonal Imagery in Japanese Art; The Seleucid Empire (323-64 B.C.) Senufo Arts and Poro Initiation in Northern Côte d'Ivoire;

The Society for Japanese Art (SJA) provides an inspiring platform for sharing knowledge and experience regarding every aspect of the visual and applied arts of Japan. ... is published twice a year by the Society for Japanese Art and packed with lavishly illustrated research papers and essays. Inside of Andon. Afbeelding. Become a SJA member ...

From the mid-sixteenth century, writing boxes and writing tables (bundai) were prepared in sets. Momoyama-period (1573-1615) writing boxes are recognized for their bold designs. A new style, characterized by asymmetrical compositions, often depicting autumn grasses executed in flat maki-e (hiramaki-e) is associated with the Kōdaiji Temple in ...