Methadone Clinic Business Plan [Sample Template]

By: Author Tony Martins Ajaero

Home » Business ideas » Healthcare and Medical » Drug & Alcohol Rehab

Do you want to start a methadone clinic and need to write a plan? If YES, here is a sample methadone clinic business plan template & FREE feasibility report.

If you are drawn towards helping people with one for or addiction or the other overcome their addiction challenges, then you are likely going to succeed when you open a methadone clinic in your city. Please note that Methadone treatment is not a “quick fix” for treating opioid addiction.

Suggested for You

- Dental Clinic Business Plan [Sample Template]

- Medical Clinic and Practice Business Plan [Sample Template]

- Weight Loss Clinic Business Plan [Sample Template]

- Wholesale Pharmacy Business Plan [Sample Template]

- Aesthetic Clinic Business Plan [Sample Template]

The National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) notes that when it comes to methadone maintenance, 12 months is considered to be the minimum length of treatment, and for some patients, treatment can go for many years in order to maintain sobriety.

If you are indeed interested in opening a methadone clinic, you should know what licensing and certification requirements would be needed from you by the state in which you would be operating from, especially as licensing caries depending on the state.

Asides licensing, you would need to know the minimum personnel that would be needed for your methadone clinic depending on the scale of business you intend to run.

At a minimum, you would require a licensed therapist, psychiatrist, nurses, and certified staff that would meet the staff-to-client ration that would meet the guidelines of the state you would be operating in.

A Sample Methadone Clinic Business Plan Template

1. industry overview.

Methadone treatment is one of the most effective and available treatment methods for opioid addiction in the united states of America and elsewhere in developed countries. As a matter of fact, one of the most well-known, but often misunderstood treatment options for opioid addiction is methadone.

The FDA-approved and highly-regulated methadone, which is distributed at outpatient clinics, manages withdrawal symptoms and side effects of opioid withdrawal and can help aid in the overall recovery process. Methadone clinic provides medication assisted treatment (MAT) that includes methadone for patients who are hoping to achieve sobriety from opioid addiction, including addiction to heroin and prescription painkillers.

Please note that methadone is administered by medical staff once a day, in a liquid solution. Methadone is only to be provided at a licensed methadone clinic under the guidance of trained healthcare providers.

Methadone clinic is a business that is grouped under the mental health and substance abuse centers industry and players in this industry includes establishments that primarily provide residential care and treatment for patients with mental illnesses, drug addiction and alcoholism.

Industry services include lodging, supervision, evaluation and counseling. Medical services may be available, though these are incidental to counseling, mental rehabilitation and support services. The mental health and substance abuse centers industry is indeed a very large industry and pretty much thriving in developed countries such as United States of America, France, United Kingdom, Germany, Australia and Italy et al.

Statistics has it that in the United States of America alone, there are about 8,216 licensed and registered mental health and substance abuse centers (methadone clinics inclusive) responsible for employing about 231,941 employees and the industry rakes in a whooping sum of $18 billion annually with an annual growth rate projected at 4.6 percent between 2014 and 2019.

It is important to state that the company holding the largest market share in the Drug & Alcohol Rehabilitation Clinics industry is Acadia Healthcare Company Inc.

A recent report released by IBISWorld shows that over the five years to 2019, industry revenue is estimated to grow an annualized 4.6 percent to $17.6 billion. In 2019 alone, revenue is estimated to grow 3.0 percent. Due to a broad range of focuses and treatment approaches offered by programs, profit margins vary significantly between operators.

Some of the factors that encourages entrepreneurs to open their own methadone clinic could be that the business is a thriving business and most methadone clinics get support and grants from government and donor agencies.

In conclusion, in order to become successful as a methadone clinic operator, you should be able to find it pretty easy to connect with people and constructively discuss their problems and issues. Excellent written and verbal communications skills and an analytical approach will serve you well in this line of business. Plus, you should know how to reach out to your target market and partner with the government and NGOs.

2. Executive Summary

Jason Collins® Methadone Clinic, Inc. is a standard and licensed methadone clinic that will be located in the heart of Rio Rancho – New Mexico in a neatly renovated and secured spacious clinic facility. Our methadone clinic is specifically designed and equipped with the needed facilities / gadgets to give comfort and security to all our patients irrespective of the religious affiliations, their race, and health condition.

Jason Collins® Methadone Clinic, Inc. will carry out standard methadone maintenance and treatments, in coordination with the other medication assisted treatment programs (including individual, group and family counseling, 12-step programs, and community-based resources), with the aim to effectively fight opioid addiction.

We will manage withdrawal symptoms and side effects of opioid withdrawal and can help aid in the overall recovery process. We will adhere to all standards and regulations to ensure patients get the exact methadone dosage they need in the time they need it in order to achieve their goals of long-term sobriety.

Jason Collins® Methadone Clinic, Inc. is a family owned and managed business that believe in the passionate pursuit of excellence and financial success with uncompromising services and integrity which is why we have decided to venture into the mental health and substance abuse centers industry by establishing our own methadone clinic.

We are certain that our values will help us drive the business to enviable heights and also help us attract the numbers of inpatients and outpatients customers that will make our facility fully occupied year in year out.

Despite the fact that we are a methadone clinic, we are going to be a health conscious and customer-centric with a service culture that will be deeply rooted in the fabric of our organizational structure and indeed at all levels of the organization.

With that, we know that we will be enables to consistently achieve our set business goals, increase our profitability and reinforce our positive long-term relationships with our clientele (inpatient and outpatient clines), partners (vendors), and all our employees as well.

Jason Collins® Methadone Clinic, Inc. is a family business that is owned and managed by Dr. Jason Collins and his immediate family.

Dr. Jason Collins is a licensed therapist, and psychiatrist with well over 25 years of experience working for leading brand in the industry. He has a Master’s Degree in Public Health and he is truly passionate when it comes to treating people who are addicted to drugs, and opioids et al.

3. Our Products and Services

Jason Collins® Methadone Clinic, Inc. is set to operate a standard methadone clinic in Rio Rancho – New Mexico. The fact that we want to become a force to reckon with in the mental health and substance abuse centers industry means that we will provide our patients with the needed treatments and care.

In all that we do, we will ensure that our inpatients and outpatients are satisfied and are willing to recommend our clinic to their family members and friends.

We are in the methadone clinic line of business to deliver excellent services and to make profits and we are willing to go the extra mile within the law of the United States to achieve our business goals, aims and objectives. We will offer the following services;

- Provide medication assisted treatment (MAT) that includes methadone for patients who are hoping to achieve sobriety from opioid addiction, including addiction to heroin and prescription painkillers

- Provide standard methadone maintenance and treatments, in coordination with the other medication assisted treatment programs (including individual, group and family counseling, 12-step programs, and community-based resources), with the aim to effectively fight opioid addiction

- Manage withdrawal symptoms and side effects of opioid withdrawal and can help aid in the overall recovery process.

4. Our Mission and Vision Statement

- Our vision is to become the number one choice when it comes to methadone maintenance and treatments in the whole of New Mexico and also to be amongst the top 5 methadone clinic facilities in the United States of America within the next 5 years.

- Our mission is to build a methadone clinic that will contribute in no smaller measure in reducing addictions and mental health ailments by providing medication assisted treatment (MAT) that includes methadone for patients who are hoping to achieve sobriety from opioid addiction, including addiction to heroin and prescription painkillers in the whole of Rio Rancho – New Mexico and environs.

- We want to meet and surpass the needs of all our patients and to build a profitable and successfully business.

Our Business Structure

Jason Collins® Methadone Clinic, Inc. is a business that will be built on a solid foundation. From the outset, we have decided to recruit only qualified professionals (methadone clinic workers administrator, nurse’s aides, medication management counselors, psychiatrists, and rehabilitation counselors) to man various job positions in our organization.

We are quite aware of the rules and regulations governing the mental health and substance abuse centers industry which is why we decided to recruit only well experienced and qualified employees as foundational staff of the organization.

We hope to leverage on their expertise to build our business brand to be well accepted in New Mexico and the whole of the United States.

When hiring, we will look out for applicants that are not just qualified and experienced, but homely, honest, customer centric and are ready to work to help us build a prosperous business that will benefit all the stake holders (the owners, workforce, and customers).

As a matter of fact, profit-sharing arrangement will be made available to all our management staff and it will be based on their performance for a period of five years or more. This are the positions that will be available at Jason Collins® Methadone Clinic, Inc.;

- Chief Medical Director

- Facility Administrator (Human Resources and Admin Manager)

- Addiction Treatment Specialist / Nurse

- Sales and Marketing Executive

- Accounting Officer

- Security Officer

5. Job Roles and Responsibilities

Chief Medical Director:

- Increases management’s effectiveness by recruiting, selecting, orienting, training, coaching, counseling, and disciplining managers; communicating values, strategies, and objectives; assigning accountabilities; planning, monitoring, and appraising job results; developing incentives; developing a climate for offering information and opinions; providing educational opportunities.

- Creating, communicating, and implementing the organization’s vision, mission, and overall direction – i.e. leading the development and implementation of the overall organization’s strategy.

- Responsible for fixing prices and signing business deals

- Responsible for providing direction for the business

- Responsible for signing checks and documents on behalf of the company

- Evaluates the success of the organization

- Reports to the board.

Facility Administrator (Admin and HR Manager)

- Responsible for overseeing the smooth running of HR and administrative tasks for the organization

- Design job descriptions with KPI to drive performance management for clients

- Regularly hold meetings with key stakeholders to review the effectiveness of HR Policies, Procedures and Processes

- Maintains office supplies by checking stocks; placing and expediting orders; evaluating new products.

- Ensures operation of equipment by completing preventive maintenance requirements; calling for repairs.

- Defining job positions for recruitment and managing interviewing process

- Carrying out staff induction for new team members

- Responsible for training, evaluation and assessment of employees

- Responsible for arranging travel, meetings and appointments

- Updates job knowledge by participating in educational opportunities; reading professional publications; maintaining personal networks; participating in professional organizations.

- Oversee the smooth running of the daily home activities.

Addiction Treatment Specialist/Nurse

- Manage withdrawal symptoms and side effects of opioid withdrawal and can help aid in the overall recovery process

- Develop a treatment plan in consultation with other professionals, such as doctors, therapists, and psychologists

- Create rehabilitation or treatment plans based on clients’ values, strengths, limitations, and goals

- Assist patients in creating strategies to develop their strengths and adjust to their limitations

- Monitor patients progress and adjust the rehabilitation or treatment plan as necessary

- Advocate for the rights of people who are just coming out of drug addictions and alcoholism to live in the community and work in the job of their choice.

Marketing and Sales Executive

- Identify, prioritize, and reach out to new clients, and business opportunities et al

- Identifies development opportunities; follows up on development leads and contacts

- Writing winning proposal documents, negotiate fees and rates in line with organizations’ policy

- Responsible for handling business research, market surveys and feasibility studies for clients

- Responsible for supervising implementation, advocate for the customer’s needs, and communicate with clients

- Develop, execute and evaluate new plans for expanding increase sales

- Document all customer contact and information

- Represent Jason Collins® Methadone Clinic, Inc. in strategic meetings

- Help increase sales and growth for Jason Collins® Methadone Clinic, Inc.

Accountant/Cashier

- Responsible for preparing financial reports, budgets, and financial statements for the organization

- Provides managements with financial analyses, development budgets, and accounting reports; analyzes financial feasibility for the most complex proposed projects; conducts market research to forecast trends and business conditions.

- Responsible for financial forecasting and risks analysis.

- Performs cash management, general ledger accounting, and financial reporting for the organization

- Responsible for developing and managing financial systems and policies

- Responsible for administering payrolls

- Ensuring compliance with taxation legislation

- Handles all financial transactions for Jason Collins® Methadone Clinic, Inc.

- Serves as internal auditor for Jason Collins® Methadone Clinic, Inc.

Security Officers

- Ensure that the clinic facility is secured at all time

- Control traffic and organize parking

- Give security tips to staff members from time to time

- Patrols around the building on a 24 hours basis

- Submit security reports weekly

- Any other duty as assigned by the facility administrator

- Responsible for cleaning the clinic facility at all times

- Ensure that toiletries and supplies don’t run out of stock

- Assist our inpatients and outpatients when they need to take their bath and carry out other household tasks

- Cleans both the interior and exterior of the facility

- Handle any other duty as assigned by the facility manager

6. SWOT Analysis

Jason Collins® Methadone Clinic, Inc. is set to become one of the leading methadone clinics in New Mexico which is why we are willing to take our time to cross every ‘Ts’ and dot every ‘Is’ as it relates to our business. We want our methadone clinic to be the number one choice of all those hoping to achieve sobriety from opioid addiction, including addiction to heroin and prescription painkillers in Rancho and other cities in New Mexico.

We know that if we are going to achieve the goals that we have set for our business, then we must ensure that we build our business on a solid foundation. We must ensure that we follow due process in setting up the business.

Even though our Chief Medical Director (owner) has a robust experience in treating people who are hoping to achieve sobriety from opioid addiction, including addiction to heroin and prescription painkillers.

We still went ahead to hire the services of business consultants that are specialized in setting up new businesses to help our organization conduct detailed SWOT analysis and to also provide professional support in helping us structure our business to indeed become a leader in the mental health and substance abuse centers industry.

This is the summary of the SWOT analysis that was conducted for Jason Collins® Methadone Clinic, Inc.;

Our strength lies in the fact that we have a team of well qualified professionals manning various job positions in our organization.

As a matter of fact, they are some of the best hands in the whole of Rio Rancho – New Mexico. Our location, the Business model we will be operating on (inpatient and outpatient treatments), well equipped and secured clinic facility and our excellent customer service culture will definitely count as a strong strength for us.

Jason Collins® Methadone Clinic, Inc. is a new business which is own by an individual (family), and we may not have the financial muscle to sustain the kind of publicity we want to give our business and also to attract some of the highly experienced hands in the mental health and substance abuse centers industry in the United States of America.

- Opportunities:

Federal funding for Medicare and Medicaid has increased during the period as states have expanded Medicaid coverage to a greater number of low-income individuals. An increase in coverage enables more individuals struggling with substance use and mental illness to access industry services.

Currently, an estimated 41.9 percent of industry revenue is derived from Medicaid and Medicare reimbursement payments. in 2023, federal funding for Medicare and Medicaid is expected to increase, presenting a potential opportunity for the industry.

Individuals seeking treatment for mental health or substance use disorders have many options in regard to types of providers and treatment models.

As a result, industry operators experience external competition from numerous sources, including from short-term inpatient and outpatient service providers in the Mental Health and Substance Abuse Clinics industry. External competition is anticipated to remain high in 2019, posing a potential threat to operators in the Mental Health and Substance Abuse Centers industry.

7. MARKET ANALYSIS

- Market Trends

A notable trend shows that the revenue and wages for methadone clinics have largely been affected due to the recession and also a slight fund drop in 2012 from federal funding of Medicaid and Medicare as a result of a rise in premiums but the effect is wearing off as the industry has largely recovered.

Also, the economy which is constantly improving is expected to boost revenue for the methadone clinic business industry from 2015 to 2022. More companies entering into this industry are doing so due to the fact that there is an increasing focus on outpatient services, which are considered less costly than inpatient care, and which is also more desirable for insurance providers.

The demand for methadone clinics is largely driven by the availability of various factors such as new drugs and treatments, funding policies as well as insurance programs. Profitability for individual facilities depends on controlling costs as well as referrals.

Large scale methadone clinics usually have more advantage when purchasing as well as marketing to sources that would provide these referrals. However, small scale companies have more leverage in competition by providing superior service to patients, integration of treatments with follow-up procedures, and specialist treatment.

Lastly, most emergency physicians have treated methadone maintenance therapy (MMT) clients in the ED, and have dealt with withdrawal, missed appointments, and overdose.

No doubt the mental health and substance abuse centers industry will continue to grow and become more profitable because the aging baby-boomer generation in United States are expected to drive increasing demand for this specialized services and care.

8. Our Target Market

Anyone can walk into an MMT clinic and request treatment. Initial screening exams and interviews determine the applicant’s eligibility and the process includes an assessment of their readiness to accept treatment. Ongoing, if not daily interventions, are required to keep the patient in the system and off the opioid.

The addiction severity index collects basic information, and it can be used to track progress. Much of the information is supplied by the addict, and truthfulness on their part is paramount for success.

In view of the above, the fact that we are going to open our doors to a wide range of customers does not in any way stop us from abiding by the rules and regulations governing the mental health and substance abuse centers industry in the United States.

Our staff are well – trained to effectively service our customers and give them value for their monies. Our customers can be categorized into the following;

- Everyone who is hoping to achieve sobriety from opioid addiction, including addiction to heroin and prescription painkillers amongst others.

Our Competitive Advantage

To be highly competitive in the mental health and substance abuse centers industry means that you should be able to secure a conducive and secured clinic facility, deliver consistent quality service and should be able to record good testimonial of changed lives; of people who are hoping to achieve sobriety from opioid addiction, including addiction to heroin and prescription painkillers in and around Rio Rancho – New Mexico.

Jason Collins® Methadone Clinic, Inc. is coming into the market well prepared to favorably compete in the industry. Our clinic facility is well positioned (centrally positioned) and visible, we have good security and the right ambience for people who are hoping to achieve sobriety from opioid addiction, including addiction to heroin and prescription painkillers.

Our staff are well groomed in all aspect of methadone clinic and treatment services and all our employees are trained to provide customized customer service to all our inpatient and outpatient customers. Our services will be carried out by highly trained professional who know what it takes to give our highly esteemed inpatients and outpatients value for their money.

Lastly, all our employees will be well taken care of, and their welfare package will be among the best within our category (startups methadone clinic business and other related businesses in the United States) in the industry. It will enable them to be more than willing to build the business with us and help deliver our set goals and achieve all our business aims and objectives.

9. SALES AND MARKETING STRATEGY

- Sources of Income

Jason Collins® Methadone Clinic, Inc. will ensure that we do all we can to maximize the business by generating income from every legal means within the scope of our industry. We will generate income by offering the following services;

10. Sales Forecast

One thing is certain, there would always be patients who are hoping to achieve sobriety from opioid addiction, including addiction to heroin and prescription painkillers who would need the services of methadone clinic.

We are well positioned to take on the available market in Rio Rancho – New Mexico and we are quite optimistic that we will meet our set target of generating enough income / profits from the first six month of operations and grow our methadone clinic business and our inpatients and outpatients’ base.

We have been able to critically examine the methadone clinic services market and we have analyzed our chances in the industry and we have been able to come up with the following sales forecast. The sales projections are based on information gathered on the field and some assumptions that are peculiar to similar startups in Rio Rancho – New Mexico.

Below is the sales projection for Jason Collins® Methadone Clinic, Inc., it is based on the location of our clinic and of course the wide range of related services that we will be offering;

- First Fiscal Year (FY1): $75,000 (From Self – Pay Clients / Patients): $150,000 (From Health Insurance Companies)

- Second Fiscal Year (FY2): $150,000 (From Self – Pay Clients / Patients): $350,000 (From Health Insurance Companies)

- Third Fiscal Year (FY3): $200,000 (From Self – Pay Clients / Patients): $650,000 (From Health Insurance Companies)

N.B : This projection is done based on what is obtainable in the industry and with the assumption that there won’t be any major economic meltdown and natural disasters within the period stated above. Please note that the above projection might be lower and at the same time it might be higher.

- Marketing Strategy and Sales Strategy

The marketing and sales strategy of Jason Collins® Methadone Clinic, Inc. will be based on generating long-term personalized relationships with our inpatients and outpatients. In order to achieve that, we will ensure that we offer top notch all – round methadone clinic services at affordable prices compare to what is obtainable in New Mexico and other state in the US.

All our employees will be well trained and equipped to provide excellent and knowledgeable services as it relates to our business. We know that if we are consistent with offering high quality service delivery and excellent customer service, we will increase the number of our inpatients and outpatients by more than 25 percent for the first year and then more than 40 percent subsequently.

Before choosing a location for Jason Collins® Methadone Clinic, Inc., we conducted a thorough market survey and feasibility studies in order for us to be able to be able to penetrate the available market and become the preferred choice for patients who are hoping to achieve sobriety from opioid addiction, including addiction to heroin and prescription painkillers in Rio Rancho and other cities in New Mexico.

We have detailed information and data that we were able to utilize to structure our business to attract the numbers of customers we want to attract per time.

We hired experts who have good understanding of the mental health and substance abuse centers industry to help us develop marketing strategies that will help us achieve our business goal of winning a larger percentage of the available market in New Mexico.

In summary, Jason Collins® Methadone Clinic, Inc. will adopt the following sales and marketing approach to win customers over;

- Introduce our business by sending introductory letters to patients who are hoping to achieve sobriety from opioid addiction, including addiction to heroin and prescription painkillers and other stake holders in and around Rio Rancho – New Mexico

- Advertise our business in community – based newspapers, local TV and local radio stations

- List our business on yellow pages ads (local directories)

- Leverage on the internet to promote our business

- Engage in direct marketing

- Leverage on word of mouth marketing (referrals)

- Enter into business partnership with prisons, government agencies and NGOs that work with drug addicts, pornography addicts and other substance abusers.

- Attend drug and substance abuse related seminars/expos.

11. Publicity and Advertising Strategy

We are in the methadone clinic business to become one of the market leaders and also to maximize profits hence we are going to explore all available conventional and non – conventional means to promote Jason Collins® Methadone Clinic, Inc.

Jason Collins® Methadone Clinic, Inc. has a long – term plan of building methadone clinic facilities in key cities in the United States of America which is why we will deliberately build our brand to be well accepted in Rio Rancho – New Mexico before venturing out.

As a matter of fact, our publicity and advertising strategy is not solely for winning inpatients and outpatients (customers) over but to effectively communicate our brand to the general public. Here are the platforms we intend leveraging on to promote and advertise Jason Collins® Methadone Clinic, Inc.;

- Place adverts on both print (community – based newspapers and magazines) and electronic media platforms

- Sponsor relevant community programs that appeals to people who are addicted to drugs, alcohol and other substances

- Leverage on the internet and social media platforms like; Instagram, Facebook, twitter, YouTube, Google + et al to promote our brand

- Install our Bill Boards on strategic locations all around Rio Rancho – New Mexico

- Engage in roadshow from time to time in location with growing population of people prone to drug and substance abuse

- Distribute our fliers and handbills in target areas with high concentration of drug addicts and alcoholics

- Ensure that all our workers wear our branded shirts and our facility and all our vehicles are well branded with our company’s logo et al.

12. Our Pricing Strategy

In as much as methadone treatments are never free, they are an affordable option for those seeking care. The range of methadone treatment costs varies by clinic, and may be covered by private and public insurance, as well as Medicaid. Players in this industry offers methadone treatment that is covered by most insurance providers, and Medicaid.

Jason Collins® Methadone Clinic, Inc. will work towards ensuring that all our services are offered at highly competitive prices compare to what is obtainable in The United States of America. Be that as it may, we have put plans in place to offer discount services once in a while and also to reward our loyal inpatients and outpatients especially when they refer clients to us.

- Payment Options

The payment policy adopted by Jason Collins® Methadone Clinic, Inc. is all inclusive because we are quite aware that different customers prefer different payment options as it suits them but at the same time, we will ensure that we abide by the financial rules and regulation of the United States of America. Here are the payment options that Jason Collins® Methadone Clinic, Inc. will make available to her clients;

- Payment via bank transfer

- Payment with cash

- Payment via online bank transfer

- Payment via check

- Payment via Point of Sale Machines (POS Machine)

- Payment via bank draft

- Payment via mobile money

In view of the above, we have chosen banking platforms that will enable our client make payment for our treatment fee in our methadone clinic without any stress on their part. Our bank account numbers will be made available on our website and promotional materials to clients who may want to deposit cash or make online transfer for our services.

13. Startup Expenditure (Budget)

If you are looking towards starting a methadone clinic business, then you should be ready to go all out to ensure that you raise enough capital to cover some of the basic expenditure that you are going to incur. The truth is that starting this type of business does not come cheap.

You would need money to secure a standard clinic facility big enough to accommodate the number of inpatients you plan accommodating per time, you could need money to acquire medical supplies and you would need money to pay your workforce and pay bills for a while until the revenue you generate from the business becomes enough to pay them.

The items listed below are the basics that we would need when starting our methadone clinic business in the United States;

- The total fee for registering the business in the United States – $750.

- Legal expenses for obtaining licenses and permits – $1,500.

- Marketing promotion expenses for the grand opening of Jason Collins® Methadone Clinic, Inc. in the amount of $3,500 and as well as flyer printing (2,000 flyers at $0.04 per copy) for the total amount of – $3,580.

- The cost for hiring business consultant – $2,500.

- The cost for the purchase of insurance (general liability, workers’ compensation and property casualty) coverage at a total premium – $3,400.

- The cost for leasing a standard and secured facility in Rio Rancho – New Mexico for 2 years – $250,000

- The cost for facility remodeling – $50,000.

- Other start-up expenses including stationery ($500) and phone and utility deposits ($2,500).

- The total cost for computer software (Accounting Software, Payroll Software, CRM Software, Microsoft Office, QuickBooks Pro, drug interaction software, Physician Desk Reference software) – $7,000

- The total cost for Nurse and Drugs Supplies (Injections, Bandages, Scissors, et al) – $3,000

- Operational cost for the first 3 months (salaries of employees, payments of bills et al) – $100,000

- The cost for start-up inventory (stocking with a wide range of products such as toiletries, food stuffs and drugs et al) – $50,000

- Storage hardware (bins, rack, shelves,) – $3,720

- The cost for the purchase of furniture and gadgets (Beds, Computers, Printers, Telephone, TVs, tables and chairs et al): $4,000.

- The cost of Launching a Website: $700

- Miscellaneous: $10,000

We would need an estimate of seven hundred and fifty thousand dollars ($750,000) to successfully set up our methadone clinic in Rio Rancho – New Mexico. Please note that this amount includes the salaries of all the staff for the first month of operation.

Generating Funds/Startup Capital for Jason Collins® Methadone Clinic, Inc.

Jason Collins® Methadone Clinic, Inc. is a family business that is solely owned and financed by Dr. Jason Collins and his immediate family members.

They do not intend to welcome any external business partners which is why he has decided to restrict the sourcing of the start – up capital to 3 major sources. These are the areas Jason Collins® Methadone Clinic, Inc. intends to generate our start – up capital;

- Generate part of the start – up capital from personal savings

- Source for soft loans from family members and friends

- Apply for loan from my Bank

N.B: We have been able to generate about $200,000 (Personal savings $150,000 and soft loan from family members $50,000) and we are at the final stages of obtaining a loan facility of $550,000 from our bank. All the papers and document have been signed and submitted, the loan has been approved and any moment from now our account will be credited with the amount.

14. Sustainability and Expansion Strategy

The future of a business lies in the numbers of loyal customers that they have, the capacity and competence of the employees, their investment strategy and the business structure. If all of these factors are missing from a business (company), then it won’t be too long before the business close shop.

One of our major goals of starting Jason Collins® Methadone Clinic, Inc. is to build a business that will survive off its own cash flow without the need for injecting finance from external sources once the business is officially running.

We know that one of the ways of gaining approval and winning customers over is to offer treatments and services in our methadone clinic a little bit cheaper than what is obtainable in the market and we are well prepared to survive on lower profit margin for a while.

Jason Collins® Methadone Clinic, Inc. will make sure that the right foundation, structures and processes are put in place to ensure that our staff welfare are well taken of. Our company’s corporate culture is designed to drive our business to greater heights and training and retraining of our workforce is at the top burner.

As a matter of fact, profit-sharing arrangement will be made available to all our management staff and it will be based on their performance for a period of three years or more. We know that if that is put in place, we will be able to successfully hire and retain the best hands we can get in the industry; they will be more committed to help us build the business of our dreams.

Check List/Milestone

- Business Name Availability Check: Completed

- Business Registration: Completed

- Opening of Corporate Bank Accounts: Completed

- Securing Point of Sales (POS) Machines: Completed

- Opening Mobile Money Accounts: Completed

- Opening Online Payment Platforms: Completed

- Application and Obtaining Tax Payer’s ID: In Progress

- Application for business license and permit: Completed

- Purchase of Insurance for the Business: Completed

- Leasing of facility and remodeling the clinic facility: In Progress

- Conducting Feasibility Studies: Completed

- Generating capital from family members: Completed

- Applications for Loan from the bank: In Progress

- Writing of Business Plan: Completed

- Drafting of Employee’s Handbook: Completed

- Drafting of Contract Documents and other relevant Legal Documents: In Progress

- Design of The Company’s Logo: Completed

- Graphic Designs and Printing of Packaging Marketing / Promotional Materials: In Progress

- Recruitment of employees: In Progress

- Purchase of medical equipment and vans et al: In Progress

- Purchase of the needed furniture, racks, shelves, computers, electronic appliances, office appliances and CCTV: In progress

- Creating Official Website for the Company: In Progress

- Creating Awareness for the business both online and around the community: In Progress

- Health and Safety and Fire Safety Arrangement (License): Secured

- Opening party / launching party planning: In Progress

- Establishing business relationship with players in key industries, NGOs, government and third – party services providers: In Progress

Overview of Opioid Treatment Program Regulations by State

Restrictive rules put evidence-based medication treatment out of reach for many.

- Overview of Opioid Treatment Program Regulations by State (PDF)

Navigate to:

- Table of Contents

Opioid treatment programs (OTPs) are the only health care facilities that can offer patients all three forms of FDA-approved medication for opioid use disorder (OUD): methadone, buprenorphine, and injectable extended-release naltrexone. 1 But Pew found that nearly all states have rules governing OTPs that are not based in evidence and in turn limit access to care or worsen patient experience. 2

These rules governing the establishment, operation, and provision of care at OTPs exist at both the federal and state levels: The federal government establishes baseline requirements for OTPs, and states layer additional requirements on top of them. 3 Although debate over the future of federal methadone regulation is ongoing, state policymakers have the opportunity to act now to improve access to this medication and the quality of OTP services, as well as remove rules that go beyond federal restrictions and limit access to care. 4

This chartbook examines OTP regulations across all 50 states and the District of Columbia as of June 2021 in two areas:

Access to care: Regulations that affect the ease with which patients access care at OTPs, such as dictating whether one is located close to where they live or work, whether services are available at convenient times, or whether patients must obtain a government ID to start treatment.

Patient experience: Rules that affect how patients receive care, such as whether they receive medication to take at home or if they have to go to the clinic every day. State regulations can help or hinder access to high-quality, evidence-based care that is aligned with federal rules and tailored to meet patients’ needs.

Methadone is offered only in OTPs, which is one reason they are critical to reducing overdose deaths and providing lifesaving addiction treatment. State policymakers should review these rules and, where needed, revise them so that residents with OUD can access high-quality, lifesaving treatment.

Access to care

OTPs are not available in many communities. As of 2018, 80% of counties in the U.S., representing nearly a quarter of the population, had no OTPs. 5 Even when a facility is nearby, patients may have challenges accessing care if services aren’t available at convenient times or patients must show a government ID to receive methadone.

How states choose to regulate OTPs plays a role in how great these access challenges are.

Restrictions on new OTPs

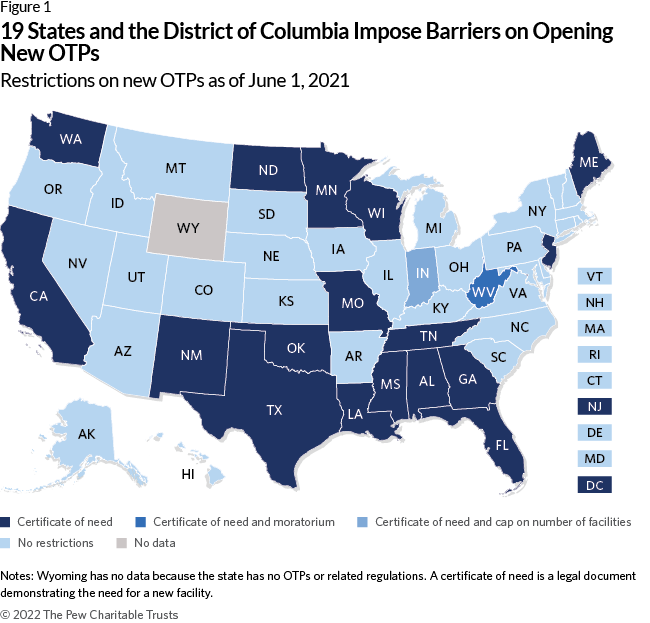

Nineteen states and the District of Columbia restrict providers from opening new OTPs in some way:

All 20 require a certificate of need, a legal document demonstrating that there is a need for a new facility. And Indiana limits the number of new facilities that can open.

West Virginia is the most restrictive state, with a legal moratorium disallowing new OTPs.

Medication units

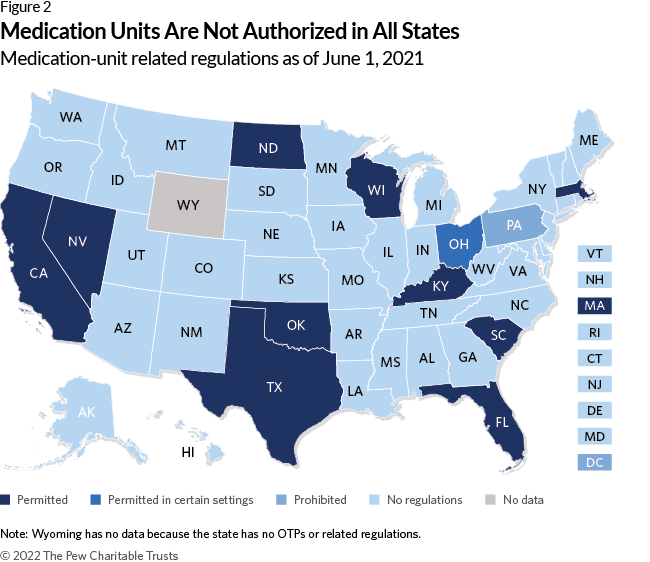

Conversely, allowing OTPs to open medication units—locations that may offer dosing and urine screens and are affiliated with an existing OTP—can make treatment more convenient for patients who receive methadone by expanding the locations where they can receive care. 6

Eleven states explicitly permit medication units, while one— Pennsylvania—prohibits them. Ohio specifically allows medication units to operate in homeless shelters, jails, prisons, local boards of public health, community health centers, residential treatment providers, small counties, and counties in Appalachia. 7

Pharmacy-related barriers

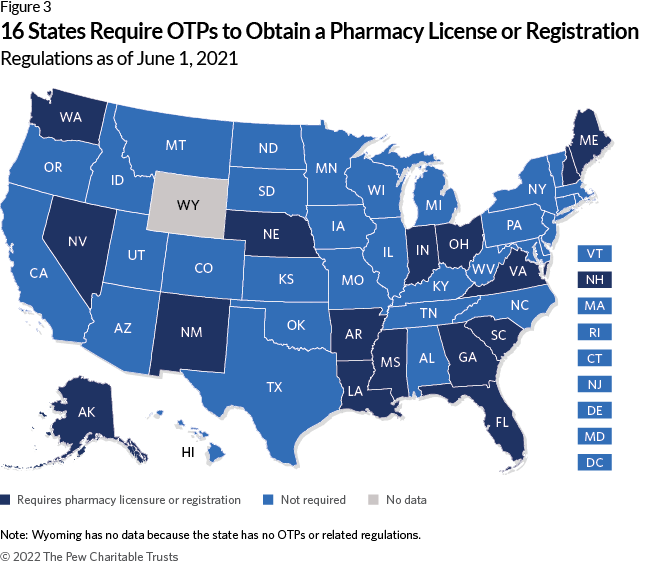

Requiring pharmacy licensure or registration.

Another barrier to establishing new OTPs mandates that they be licensed or registered as pharmacies.

This is not required by federal law. 8 Sixteen states have these rules.

Applying general pharmacy regulations to OTPs

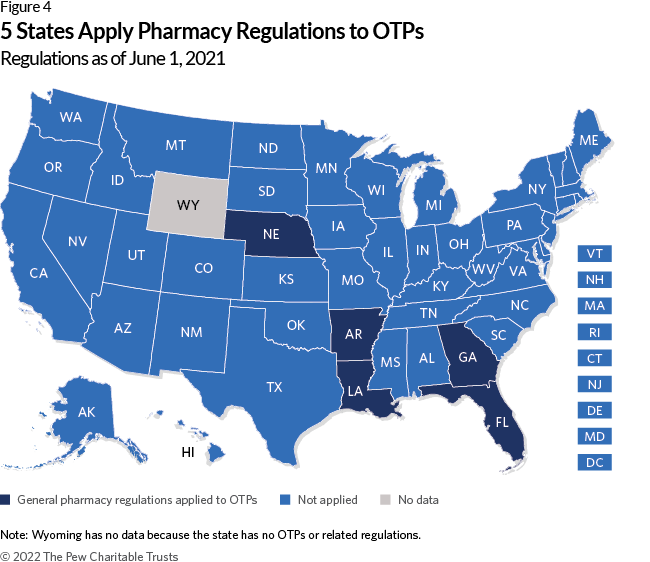

States that require OTPs to follow their general pharmacy regulations— which apply to a neighborhood drugstore that fills prescriptions for many medications that are used for multiple conditions—make establishing new OTPs even more challenging.

Five states apply general pharmacy regulations to OTPs.

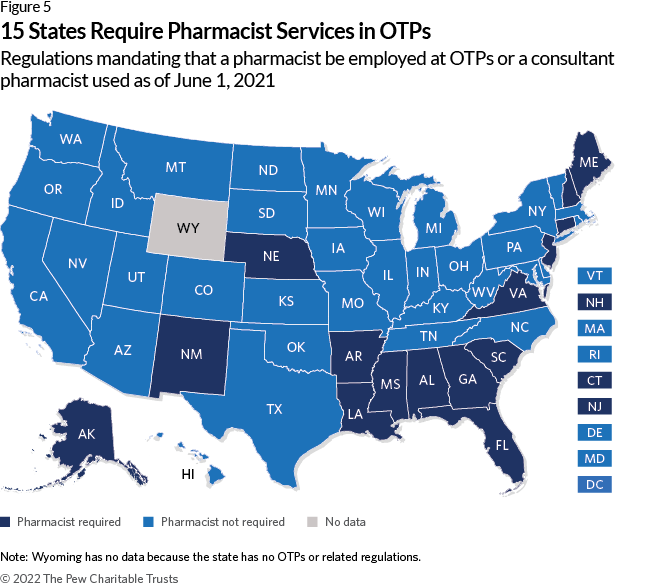

Requiring pharmacist services

Federal law allows methadone administration by a variety of licensed health care professionals including registered nurses, licensed practical nurses, or other health care professionals who are otherwise authorized to dispense opioids. 9

However, 15 states require OTPs to hire a pharmacist or a consultant pharmacist, who provides guidance on the appropriateness and safety of medication use. 10

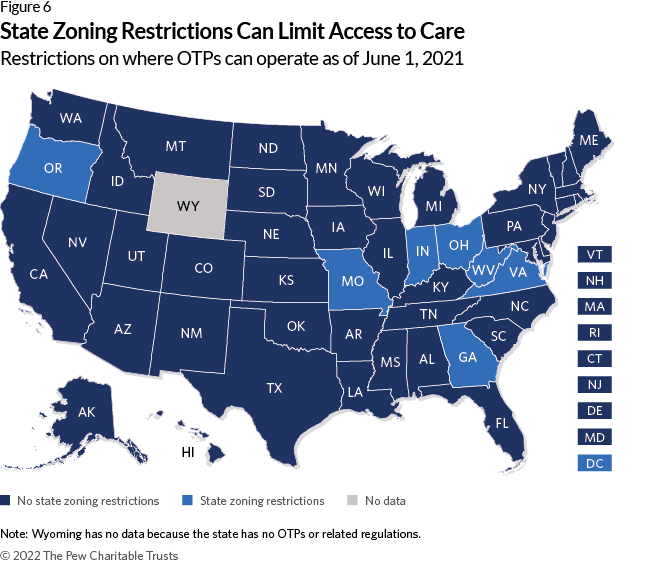

State zoning restrictions

Restrictions on where an OTP can operate, beyond those that apply to other medical facilities, is not considered to be best practice. 11

Seven states and the District of Columbia have these rules. However, in the District, the regulation supports access to care because OTPs are required to be located near public transportation.

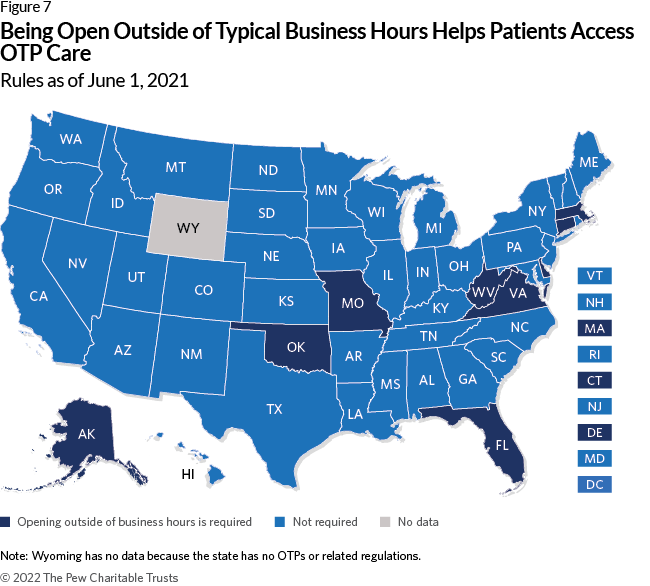

Hours of operation

Requiring OTPs to be open outside of regular business hours (e.g., outside of 8 a.m.-5 p.m.) provides flexibility for clients who may find it difficult to go to the clinic each day due to other responsibilities such as work or family obligations. 12

Nine states require OTPs to be open outside of business hours.

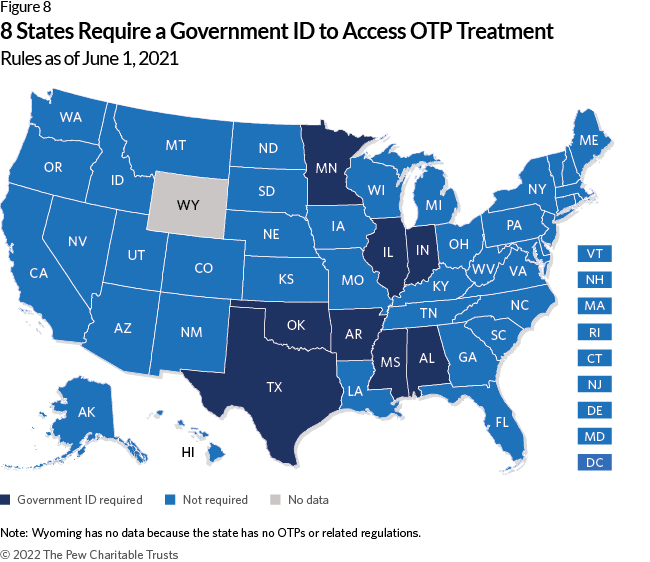

Government ID

Some people—including undocumented immigrants, people who have been incarcerated, people experiencing homelessness, and many other populations— face challenges in obtaining an ID. 13 Requiring a client to show government ID to be admitted to an OTP can be a barrier to care.

Eight states have this requirement.

Conversely, California allows OTPs to provide patient identification cards that include the individual’s photo, a unique identifier, and a physical description. 14 This allows the OTP to verify the patient’s identity before dispensing methadone without requiring a government ID.

Patient experience

Federal rules already dictate the frequency of urine drug screens and whether patients can receive take-home methadone—a supply of medication for opioid use disorder that allows patients to avoid having to go to the clinic each day—as well as other aspects of OTP care.

When states add additional rules, they further constrain providers from offering individualized, high-quality care that meets their patients’ needs.

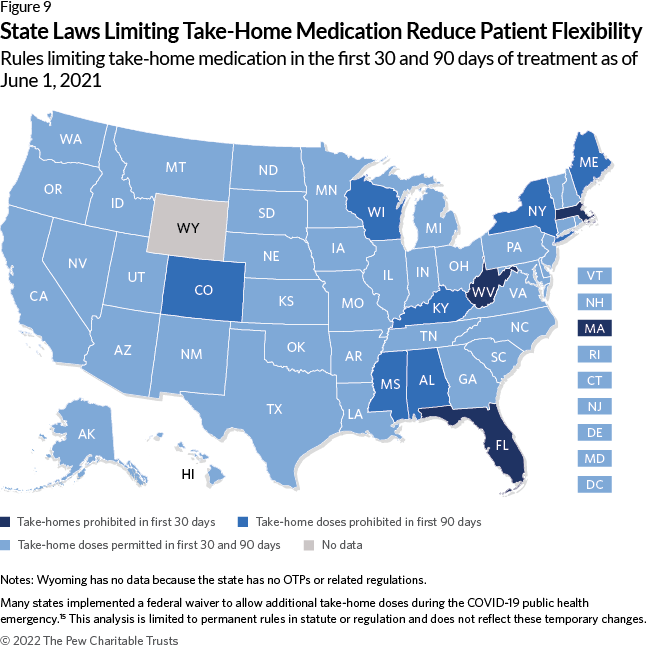

Eligibility for take-home doses

Before the COVID-19 public health emergency, federal rules allowed a single take-home dose per week in the first 90 days of treatment if patients met specific stability criteria. 16 This requirement has not been permanently changed, and only temporary flexibilities have been granted as of April 2022. 17

Ten states go beyond federal rules by prohibiting take-home doses in the first 30 days of treatment. Of these, seven states prohibit this practice during the full first 90 days of care.

Additional stability criteria

Federal rules require that patients meet eight stability criteria to receive take-home doses:

- Absence of recent abuse of drugs (opioid or non-narcotic), including alcohol.

- Regularity of clinic attendance.

- Absence of serious behavioral problems at the clinic.

- Absence of known recent criminal activity, e.g., drug dealing.

- Stability of the patient’s home environment and social relationships.

- Length of time in comprehensive maintenance treatment.

- Assurance that take-home medication can be safely stored within the patient’s home.

- Whether the rehabilitative benefit the patient derived from decreasing the frequency of clinic attendance outweighs the potential risks of diversion . 18

Ten states impose additional stability criteria. For example, Missouri also requires that patients “demonstrate a level of stability as evidenced by … employment, actively seeking employment, or attending school if not retired, disabled, functioning as a homemaker, or otherwise economically stable.” 19

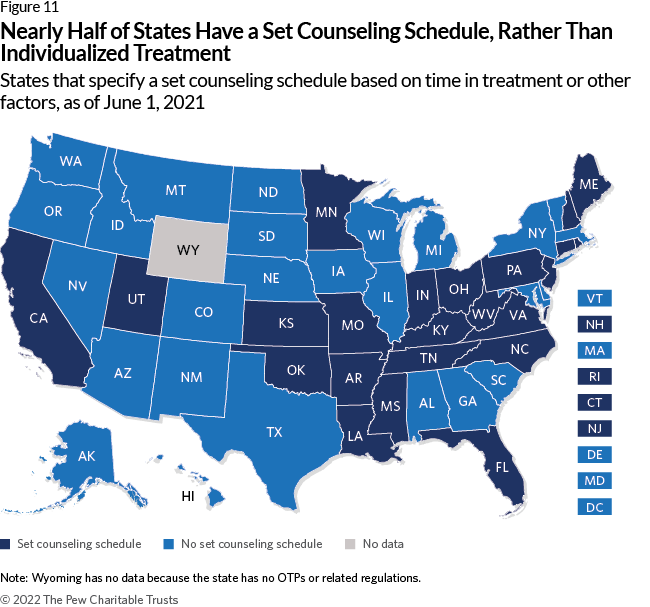

Inflexible counseling requirements

Requiring clients to participate in a set counseling schedule (e.g., a minimum number or length of sessions) to stay in treatment or receive take-home medication is not in line with federal regulations, and strict counseling requirements can reduce retention in treatment. 20

Twenty-three states impose a set counseling schedule. These rules can be tied to eligibility for take-home medication. In Oklahoma, for example, patients move through five phases of treatment based on time in treatment and compliance with program rules, including participation in a set number of individual and group counseling sessions per phase. Each phase provides more take-home doses. 21

These rules are not aligned with evidence, which shows that medication for opioid use disorder can be effective without counseling. 22

Forcing people to leave treatment for violating program rules

It’s common for people who use opioids to also use multiple substances as well as return to opioid use, even among people on medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD). 23 Although federal guidelines and recommendations list neither as a reason to end medication treatment and research supports that continuing MOUD is safer than suddenly stopping treatment, some programs “administratively discharge”—or terminate—clients because of continued drug use. 24

Only Massachusetts and South Dakota prohibit administrative discharge for not being abstinent.

All states allow administrative discharge for missed methadone doses, although federal guidelines recommend reassessing patients who miss more than four methadone doses rather than terminating their treatment. 25

All states also allow administrative discharge for nonparticipation in counseling or other ancillary services, even though the American Society of Addiction Medicine says the decision to decline these services should not affect a patient’s ability to obtain MOUD. 26

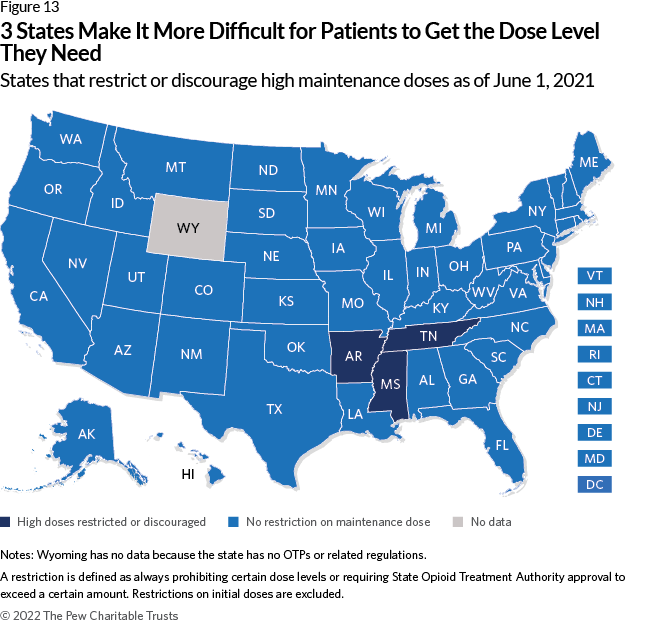

Restricting medication dosage

Doses that are too low may not effectively reduce drug cravings or use. 27 Restricting or discouraging higher doses of medication may cause patients to discontinue treatment. This restriction is also not aligned with federal guidelines or evidence, as higher doses can lead to greater reductions in drug use among patients with OUD. 28

Three states have these rules.

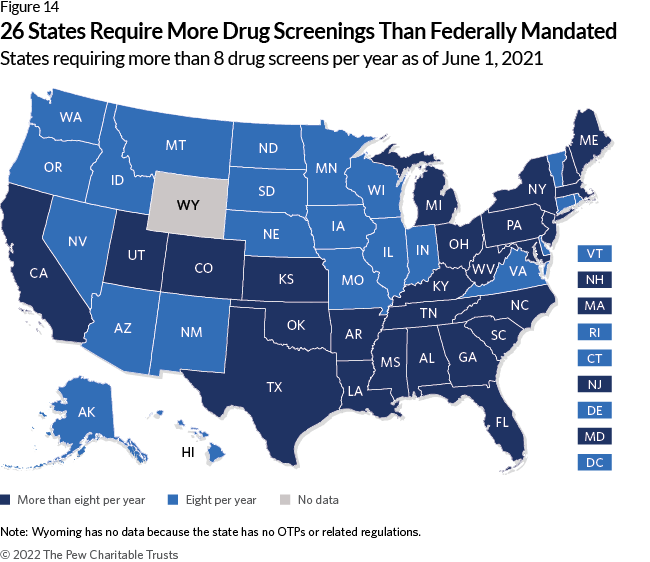

Urine drug screenings

Requiring additional tests.

Federal rules require eight drug tests per year. 29 Requiring additional tests places a burden on patients and, according to preliminary research, may not be as necessary for patient safety as once thought, and may also raise the cost of treatment. 30

Twenty-six states require more than eight annual drug screenings.

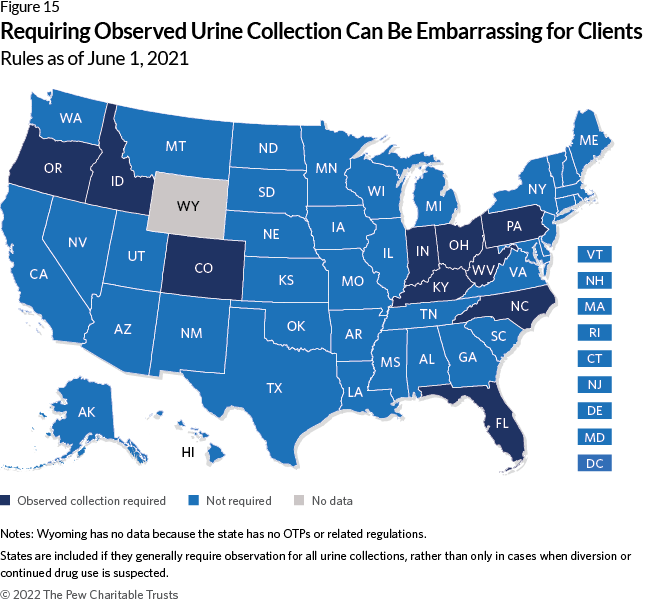

Observing urine specimen collection

Ten states have rules requiring OTPs to observe patients during urine sample collection, which can be embarrassing and degrading for clients. 31 According to one, “I don’t like somebody looking at me, or behind me … it’s not a very pleasant experience for anybody. Actually, I think it’s undignified, and I feel it’s wrong.” 32

Establishing a treatment goal not based in evidence

Evidence supports that long-term treatment can be more beneficial for patients in terms of overdose risk, employment, health, and criminal justice involvement; according to the American Society of Addiction Medicine, “There is no recommended time limit for pharmacological treatment with methadone.” 33

But eight states have rules that establish discontinuation as the goal of treatment. These regulations may encourage providers and patients to stop treatment when doing so is not necessary and can increase overdose death. 34

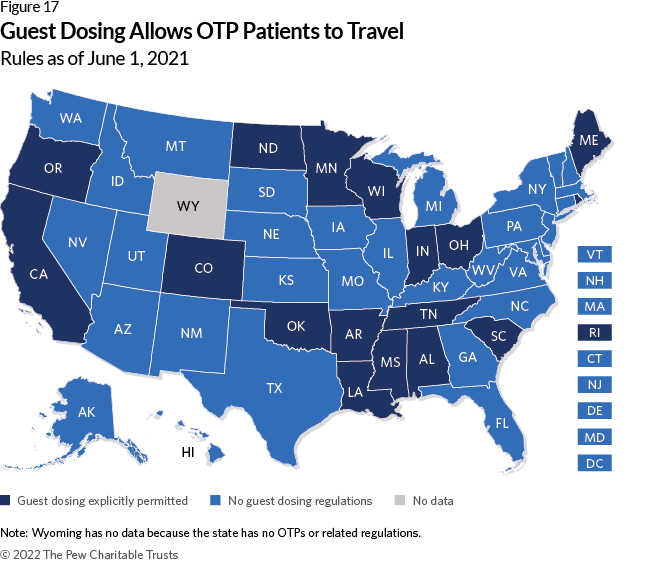

Allowing patients flexibility while traveling

Although other regulations can worsen patient experience, states can also improve it through regulations.

Explicitly allowing guest dosing— that is, temporarily getting methadone from an OTP other than the one at which someone is a patient—is one way to help. This provides flexibility for patients who are traveling. 35

Seventeen states have rules that explicitly allow this practice, though it may still be permitted in states without these regulations.

Data shows that many states make it harder for OTP patients to access and remain in treatment in a variety of ways.

As overdose deaths continue to climb, state policymakers should review these rules and make changes so that more people get the lifesaving treatment provided in these settings.

Methodology

Identifying regulatory language.

Pew reviewed both statutes and administrative codes for the District of Columbia and all states, except for Wyoming, using Lexis. Wyoming was excluded because the state does not have any OTPs or related regulations.

Initial citations were drawn from Jackson et al. (2020) and the Prescription Drug Abuse Policy System “Requirements for Licensure and Operations of Medications for Opioid Use Disorder Treatment.” 36 In addition to these sources, Pew reviewed the section of statutes providing rule-making authority to the agency that promulgated regulations in the administrative code. If either regulations or statutes referred to Board of Pharmacy oversight, Pew also examined the relevant sections of administrative code produced by that body.

Data represents state rules codified in statute and administrative code as of June 2021. It does not reflect any temporary changes such as executive orders or policy statements states may have issued due to the COVID-19 pandemic. 37

Pew developed an initial list of codes based on a review of the OTP federal guidelines and literature on best practices. Using NVivo, the research team that has years of OUD research and policy expertise initially coded five states. The regulations for each state were independently coded by two members of the research team. Pew then held a coding meeting to discuss our findings and refine the codebook, and then recoded these states. The research team then conducted a test of inter-rater reliability, which ensures consistency in coding among research team members, resolved coding discrepancies, and refined the codebook further. Pew then coded five additional states, held another coding meeting, and finalized the codebook. (See Appendix)

Quality control

Pew conducted two quality control steps—comparing our findings with existing research and verifying results with state officials.

Comparison with existing research

Pew compared the findings with previously conducted reviews of OTP regulations. 38 In most cases, disagreement between Pew’s findings and these publications were due to differences in definition or because regulations had been updated since those reviews were conducted. If we identified an error based on these comparisons, we updated our data.

Verification with state opioid treatment authorities (SOTAs)

Between June and August 2021, Pew sent the results of each jurisdiction’s regulatory review to their state opioid treatment authority, or SOTA, the official charged with overseeing OTPs. These officials were identified by a list maintained by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. 39 For Wyoming, Pew contacted the deputy administrator of the Behavioral Health Division because the state does not have a SOTA.

Each SOTA was asked to verify whether Pew’s interpretation of their state’s OTP rules was correct, and if it was not, to provide updated information.

After sending multiple reminders to each official, Pew received responses from all but 12 states (Delaware, Kansas, Mississippi, Missouri, New Hampshire, New York, Rhode Island, Tennessee, Utah, Vermont, Washington, and Wisconsin). If the SOTA disagreed with the research team’s findings, Pew either updated the research or explained the decision not to. In those cases where we did not update our findings, those discrepancies were either due to differences in definitions or because updated regulatory language was not in effect until after June 1, 2021, our cutoff date.

- The Pew Charitable Trusts, “Medications for Opioid Use Disorder Improve Patient Outcomes” (2020), https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/factsheets/2020/12/medications-for-opioid-use-disorder-improve-patient-outcomes .

- The Pew Charitable Trusts, “Improved Opioid Treatment Programs Would Expand Access to Quality Care” (2022), https://www.pewtrusts.org/-/media/assets/2022/03/improve-opioid-treatment-programs-to-expand-access.pdf .

- American Society of Addiction Medicine, “Regulation of the Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder With Methadone” (2021), https://www.asam.org/advocacy/public-policystatements/details/public-policy-statements/2021/11/16/the-regulation-of-the-treatment-of-opioid-use-disorder-with-methadone .

- M. Hawryluk, “Calls to Overhaul Methadone Distribution Intensify, but Clinics Resist,” KHN, March 3, 2022, https://khn.org/news/article/opioid-methadone-treatmentoverhaul-clinics-resist-addiction/ .

- J.H. Duff and J.A. Carter, “Location of Medication-Assisted Treatment for Opioid Addiction: In Brief” (Congressional Research Service, 2019), https://www.everycrsreport.com/files/20190624_R45782_ed39091fadf888655ebd69729c3180c3f7e550f6.pdf .

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, “OTP Services Through Medication Units” (2022), https://www.samhsa.gov/medication-assisted-treatment/become-accredited-opioid-treatment-program care; A. McBournie et al., “Methadone Barriers Persist, Despite Decades of Evidence,” Health Affairs Blog , Health Affairs, Sept. 23, 2019, https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20190920.981503/full/#_ftnref1 .

- Ohio Administrative Code, Medication Units, 5122-40-15 (2019), https://codes.ohio.gov/ohio-administrative-code/rule-5122-40-15 .

- 42 C.F.R. § 8.12 Federal Opioid Treatment Standards, https://www.ecfr.gov/cgi-bin/retrieveECFR?gp=3&SID=7282616ac574225f795d5849935efc45&ty=HTML&h=L&n=pt42.1.8&r=PART .

- University of Florida Health, “What Are the Benefits of Becoming a Consultant Pharmacist?” accessed March 21, 2022, https://cpe.pharmacy.ufl.edu/consultantpharmacist-2/what-are-the-benefits-of-becoming-a-consultant-pharmacist/ .

- J.R. Jackson et al., “Characterizing Variability in State-Level Regulations Governing Opioid Treatment Programs,” Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 115 (2020), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2020.108008 .

- K. Cioe et al., “A Systematic Review of Patients’ and Providers’ Perspectives of Medications for Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder,” Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 119 (2020), https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33138929 ; H.S. Reisinger et al., “Premature Discharge From Methadone Treatment: Patient Perspectives,” Journal of Psychoactive Drugs 41, no. 3 (2009): 285-96, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19999682 .

- A.M.W. LeBrón et al., “Restrictive ID Policies: Implications for Health Equity,” Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health 20, no. 2 (2018): 255-60, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-017-0579-3 .

- California Code of Regulations, Patient Identification System, 9 CSR 10240 (2021), https://www.law.cornell.edu/regulations/california/Cal-Code-Regs-Tit-9-SS-10240 .

- V. Baaklini et al., “Most States Eased Access to Opioid Use Disorder Treatment During the Pandemic” (2022), https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/articles/2022/06/01/most-states-eased-access-to-opioid-use-disorder-treatment-during-the-pandemic .

- 42 C.F.R. § 8.12 Federal Opioid Treatment Standards; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, “Federal Guidelines for Opioid Treatment Programs” (2015), https://store.samhsa.gov/product/Federal-Guidelines-for-Opioid-Treatment-Programs/PEP15-FEDGUIDEOTP .

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, “Methadone Take-Home Flexibilities Extension Guidance,” last modified March 3, 2022, https://www.samhsa.gov/medication-assisted-treatment/statutes-regulations-guidelines/methadone-guidance .

- 42 C.F.R. § 8.12 Federal Opioid Treatment Standards.

- Missouri Code of Regulations, Opioid Treatment Program, 9 CSR 30-3.132 (2021), https://www.law.cornell.edu/regulations/missouri/9-CSR-30-3-132 .

- 42 C.F.R. § 8.12 Federal Opioid Treatment Standards; M. Hochheimer and G.J. Unick, “Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Retention in Treatment Using Medications for Opioid Use Disorder by Medication, Race/Ethnicity, and Gender in the United States,” Addictive Behaviors 124 (2022), https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0306460321002987 .

- Oklahoma Code of Regulations, Service Phases - Phase VI, 450:70-6-17.8 et seq(2021), https://www.law.cornell.edu/regulations/oklahoma/Okla-Admin-CodeSS-450-70-6-17-8 (a sixth phase is also set out in regulations, but new patients have not been eligible for this phase since July 1, 2007).

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Medications for Opioid Use Disorder Save Lives (Washington: National Academies Press, 2019).

- The Pew Charitable Trusts, “Opioid Overdose Crisis Compounded by Polysubstance Use” (2020), https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/factsheets/2020/10/opioid-overdose-crisis-compounded-by-polysubstance-use ; A.C. Stone et al., “Methadone Maintenance Treatment Among Patients Exposed to Illicit Fentanyl in Rhode Island: Safety, Dose, Retention, and Relapse at 6 Months,” Drug and Alcohol Dependence 192 (2018): 94-97, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0376871618304721 .

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, “Federal Guidelines for Opioid Treatment Programs”; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, “Medications for Opioid Use Disorder: Treatment Improvement Protocol 63” (2021), https://store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/SAMHSA_Digital_ Download/PEP21-02-01-002.pdf; National Academies of Sciences, Medications for Opioid Use Disorder Save Lives .

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, “Medications for Opioid Use Disorder: Treatment Improvement Protocol 63.”

- American Society of Addiction Medicine, “National Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder” (2020), https://sitefinitystorage.blob.core.windows.net/sitefinity-production-blobs/docs/default-source/guidelines/npg-jam-supplement.pdf?sfvrsn=a00a52c2_2 .

- F. Faggiano et al., “Methadone Maintenance at Different Dosages for Opioid Dependence,” Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews , no. 3 (2003), https://doi.org//10.1002/14651858.CD002208 .

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, “Federal Guidelines for Opioid Treatment Programs”; J.A. Trafton, J. Minkel, and K. Humphreys, “Determining Effective Methadone Doses for Individual Opioid-Dependent Patients,” PLOS Medicine 3, no. 3, (2006): e80, https://journals.plos.org/plosmedicine/article?id=10.1371/journal.pmed.0030080 .

- Urban Survivors Union, “The Methadone Manifesto,” ( https://sway.office.com/UjvQx4ZNnXAYxhe7?ref=Link&mc_cid=9754583648&mc_eid=51fa67f051 ; G. Joseph et al., “Reimagining Patient-Centered Care in Opioid Treatment Programs: Lessons From the Bronx During COVID-19,” Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 122 (2021), https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33353790 .

- C. Strike and C. Rufo, “Embarrassing, Degrading, or Beneficial: Patient and Staff Perspectives on Urine Drug Testing in Methadone Maintenance Treatment,” Journal of Substance Use 15, no. 5 (2010): 303-12, https://doi.org/10.3109/14659890903431603 .

- National Academies of Sciences, Medications for Opioid Use Disorder Save Lives ; American Society of Addiction Medicine, “The ASAM National Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder - 2020 Focused Update” (2020), https://www.asam.org/quality-care/clinical-guidelines/national-practice-guideline .

- N. Krawczyk et al., “Opioid Agonist Treatment Is Highly Protective Against Overdose Death Among a U.S. Statewide Population of Justice-Involved Adults,” The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse 47, no. 1 (2021): 117-26, https://doi.org/10.1080/00952990.2020.1828440 .

- American Association for the Treatment of Opioid Dependence, “AATOD Guidelines for Guest Medication,” http://www.aatod.org/advocacy/policy-statements/aatodguidelines-for-guest-medication/ .

- Jackson et al., “Characterizing Variability”; Prescription Drug Abuse Policy System, Requirements for Licensure and Operations of Medications for Opioid Use Disorder Treatment, through Aug. 1, 2020, https://pdaps.org/datasets/medication-assisted-treatment-licensure-and-operations-1580241579 .

- American Society of Addiction Medicine, “COVID-19 - National and State Health Guidance,” https://www.asam.org/quality-care/clinical-guidelines/covid/national-andstate-guidance .

- Jackson et al., “Characterizing Variability”; Prescription Drug Abuse Policy System, Requirements for Licensure and Operations of Medications for Opioid Use Disorder Treatment.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, “State Opioid Treatment Authorities,” https://www.samhsa.gov/medication-assisted-treatment/sota .

How State Legislatures Can Pass Effective Policies on SUD

Like many parts of the country, Kentucky has experienced a devastating opioid crisis, with the second highest overdose death rate in the U.S. according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Measure More Than Deaths to Improve Addiction Treatment

During the first 12 months of the COVID-19 pandemic, more than 70,000 people died in the U.S. from an opioid overdose.

Don’t miss our latest facts, findings, and survey results in The Rundown

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

MORE FROM PEW

Opioid Treatment Programs: SAMHSA Makes Permanent Regulatory Flexibilities

On February 1, 2024, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, announced a final rule updating the regulations regarding Opioid Treatment Programs (OTPs) as part of the Biden Administration’s Overdose Prevention Strategy. These announced changes are the first update to the OTP regulations in over 20 years and significantly increase access to medications like methadone and buprenorphine that treat opioid use disorder by, among other things, making permanent prescribing of “take-home” doses and enabling use of telemedicine to extend OTPs to a patient’s home.

What are OTPs?

OTPs provide medication assisted treatment (MAT) for people diagnosed with opioid use disorder (OUD). MAT utilizes medications (typically methadone or buprenorphine) with psychosocial counseling and other behavioral health services to treat patients. OTPs are sometimes called methadone clinics because these clinics are the only way people can access methadone treatment for opioid use disorder. OTPs may exist in a variety of settings including intensive outpatient programs, residential programs, and hospitals, but all OTPs require a specific license certification by SAMHSA, and accreditation by an independent, SAMHSA-approved accrediting body. The OTP model has been criticized as too burdensome in restricting a patient’s ability to easily access life-saving medication and treatments for OUD. The prior requirement that methadone only be prescribed at these clinics and the prior restriction on unsupervised or take-home doses of medications used to treat OUD have historically required patients to make daily visits to an OTP, even in the outpatient setting.

What did the Final Rule change?

The final rule updates OTP certificate and accreditation standards, treatment standards related to medications dispensed by an OTP and removed language regarding the DATA Waiver. The DATA Waiver requirement was removed in January 2023. SAMHSA also released a table summarizing key changes along with the rationale for these changes.

Flexibility of Methadone Medication Take-Home Doses in OTPs

In March 2020, due to the COVID-19 Pandemic, SAMHSA issued exemptions allowing OTPs to dispense up to 28 days of “take-home methadone doses for stable patients being treated for OUD and up to 14 doses of “take-home” methadone for “less stable” patients. Originally meant to reduce the risk of spreading COVID-19, OTPs and patients widely supported these changes. These flexibilities were scheduled to sunset one year past the end of the COVID-19 Public Health Emergency (PHE) (May 11, 2024) or until a final rule was published.

This final rule created a permanent option allowing take-home medication including methadone, buprenorphine, buprenorphine combination productions, and Naltrexone. First, the rule allows patients to be able to access take-home medication doses for days when the clinic is closed. Beyond those doses, the OTP practitioner may use their discretion to dispense medications to patients for OUD subject to certain maximums. Within the first 14 days of treatment, the take-home supply is limited to maximum supply of seven days’ worth of take-home medication. Between 15-30 days of treatment, the take-home supply maximum is increased to 14 days. Finally, after 31 days, the patient may have a take-home supply up to 28 days.

Flexibility to Prescribe Medication for OUD via Telehealth without an Initial In-person Physical Evaluation

In April 2020, SAMHSA implemented regulatory flexibilities to address the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic including exempting OTPs from the requirement to perform an in-person physical evaluation for patients being treated with buprenorphine in an OTP. Notably, this flexibility did not apply to methadone. On May 9, 2023, SAMHSA extended this telehealth flexibility until one year past the end of the COVID-19 PHE, or until such time that SAMHSA published a final rule.

This final rule allows an OTP practitioner to initiate treatment of methadone or buprenorphine via telehealth without an initial in-person exam. The final rule states that if certain practitioners, including the OTP physician, primary care physician, or other authorized health care professional under the supervision of program physician determines that an evaluation of the patient can be accomplished via audio visual technology, then a licensed OTP practitioner may prescribe and dispense methadone or buprenorphine to the patient. Importantly, in the rule commentary, SAMHSA notes it is not extending the use of audio-only telehealth technology to methadone because methadone holds a higher risk profile for sedation. If audio-visual technology is not available, an audio-only device may be used to prescribe methadone but only when patient is in the presence of a licensed practitioner who is registered to prescribe and dispense controlled medications. These additional requirements significantly limit the usefulness of audio-only technology for the prescription of methadone.

SAMHSA notes that this final rule does not authorize the prescription of methadone via telehealth outside the OTP context Methadone must still be prescribed and dispensed by appropriately licensed OTP practitioners. Additionally, any medication must still be dispensed to the patient under existing OTP procedures.

Admission Criteria Changes

Additionally, the final rule removed stringent admission criteria that prevented patients from initially accessing treatment. First, the final rule removed the requirement that patients have a full year history of OUD before being able to access treatment at an OTP. Second, this final rule removes the requirement that patients under the age of 18 have two unsuccessful attempts at treatment before entering treatment at an OTP.

Scope of Practice Expansion

On the federal level, the definition of practitioner was modified to include any “health care professional who is appropriately licensed by the state to prescribe and/or dispense medications for opioid use disorder.” This means, subject to state laws, many more types of non-physician practitioners such as nurse practitioners or physician assistant may prescribe or order medication. However, some states may not allow non-physician practitioners such as certified nurse-midwives, nurse practitioner, physician assistants, or pharmacists to prescribe these medications.

Impact of the Final Rule

These increased flexibilities will vastly improve patient’s access to life-saving OTP services. Specifically, the changes regarding methadone prescribing are a crucial step forward in allowing patients access to this important medication. While these changes only apply to the OTP regulatory scheme, the introduction of take-home medications, the ability to prescribe medication through telehealth, changes to admission criteria, and expanding the scope of practitioners will allow OTPs to access more patients in a field that desperately needs more providers.

Foley is here to help you address the short- and long-term impacts in the wake of regulatory changes. We have the resources to help you navigate these and other important legal considerations related to business operations and industry-specific issues. Please reach out to the authors, your Foley relationship partner, or to our Health Care Practice Group with any questions.

Alexandra B. Maulden

Kyle Y. Faget

Related insights, massachusetts health care act dies at the end of legislative session but previews sweeping changes for the health care industry, fda: the effects of loper on the regulatory agenda, substance use disorder treatment services: 2025 physician fee schedule proposed rule would expand access and medicare coverage.

An official website of the United States government

Here’s how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock A locked padlock ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

HHS Announces Funding for Substance Use Treatment and Prevention Programs

Grants to Focus on Increasing Access to Medication-Assisted Treatment for People Battling Opioid Use Disorder

Today, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), through the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), is announcing two grant programs totaling $25.6 million that will expand access to medication-assisted treatment for opioid use disorder and prevent the misuse of prescription drugs. By reducing barriers to accessing the most effective, evidenced-based treatments, this funding reflects the priorities of HHS' Overdose Prevention Strategy , as well as its new initiative to strengthen the nation's mental health and crisis care systems.

"Every five minutes someone in our nation dies from an overdose," said Secretary Becerra. "This is unacceptable. At HHS, we are committed to addressing the overdose crisis, and one of the ways we're doing this is by expanding access to medication-assisted treatment and other effective, evidenced-based prevention and intervention strategies. We're also traveling the country to listen and learn about new and innovative ways HHS can support local communities in addressing mental health and substance use. Together, through our Overdose Prevention Strategy and National Tour to Strengthen Mental Health, we can change the way we address overdoses and save lives."

Last week, following President Joe Biden's State of the Union address, HHS kicked off a National Tour to Strengthen Mental Health in an effort to hear directly from Americans across the country about the challenges they're facing, and engage with local leaders to strengthen the mental health and crisis care systems in our communities. This funding announcement is part of this new initiative, which is focused on three aspects of the crisis Americans are facing: mental health, , suicide, and substance use.

"This funding will enhance efforts underway throughout our nation to get help to Americans who need it," said Miriam Delphin-Rittmon, Ph.D., HHS Assistant Secretary for Mental Health and Substance Use and the leader of SAMHSA. "Expanding access to evidence-based treatments and supports for individuals struggling with opioid use disorder has never been more critical. Strengthening the nation's prescribing guidelines to prevent misuse is equally critical."

The two grant programs are:

- The Strategic Prevention Framework for Prescription Drugs ( SPF Rx ) grant program provides funds for state agencies, territories, and tribal entities that have completed a Strategic Prevention Framework State Incentive Grant plan or a similar state plan to target prescription drug misuse. The grant program will raise awareness about the dangers of sharing medications, fake or counterfeit pills sold online, and over prescribing. The grant will fund a total of $3 million over five years for up to six grantees.

- The Medication-Assisted Treatment – Prescription Drug and Opioid Addiction ( MAT-PDOA ) grant program provides resources to help expand and enhance access to Medications for Opioid Use Disorder (MOUD). It will help increase the number of individuals with Opioid Use Disorder (OUD) receiving MOUD and decrease illicit opioid use and prescription opioid misuse. The grant will fund a total of $22.6 million over 5 years for up to 30 grantees. No less than $11 million will be awarded to Native American tribes, tribal organizations, or consortia.

Anyone seeking treatment options for substance misuse should call SAMHSA's National Helpline at 800-662-HELP (4357) or visit findtreatment.gov . Reporters with questions should email [email protected] .

More information on the National Tour to Strengthen Mental Health is available at https://HHS.gov/HHSTour .

Sign Up for Email Updates

Receive the latest updates from the Secretary, Blogs, and News Releases

Subscribe to RSS

Receive latest updates

Related News Releases

Biden-harris administration awards $45.1 million to expand mental health and substance use services across the lifespan, kids online health and safety task force announces recommendations and best practices for safe internet use, biden-harris administration launching initiative to build multi-state social worker licensure compact to increase access to mental health and substance use disorder treatment and address workforce shortages, related blog posts.

The HHS Office for Civil Rights Celebrates National Recovery Month

Media inquiries.

For general media inquiries, please contact [email protected] .

Disclaimer Policy: Links with this icon ( ) mean that you are leaving the HHS website.

- The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) cannot guarantee the accuracy of a non-federal website.

- Linking to a non-federal website does not mean that HHS or its employees endorse the sponsors, information, or products presented on the website. HHS links outside of itself to provide you with further information.

- You will be bound by the destination website's privacy policy and/or terms of service when you follow the link.

- HHS is not responsible for Section 508 compliance (accessibility) on private websites.

For more information on HHS's web notification policies, see Website Disclaimers .

- Skip to main content