- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Federalist Papers

By: History.com Editors

Updated: June 22, 2023 | Original: November 9, 2009

The Federalist Papers are a collection of essays written in the 1780s in support of the proposed U.S. Constitution and the strong federal government it advocated. In October 1787, the first in a series of 85 essays arguing for ratification of the Constitution appeared in the Independent Journal , under the pseudonym “Publius.” Addressed to “The People of the State of New York,” the essays were actually written by the statesmen Alexander Hamilton , James Madison and John Jay . They would be published serially from 1787-88 in several New York newspapers. The first 77 essays, including Madison’s famous Federalist 10 and Federalist 51 , appeared in book form in 1788. Titled The Federalist , it has been hailed as one of the most important political documents in U.S. history.

Articles of Confederation

As the first written constitution of the newly independent United States, the Articles of Confederation nominally granted Congress the power to conduct foreign policy, maintain armed forces and coin money.

But in practice, this centralized government body had little authority over the individual states, including no power to levy taxes or regulate commerce, which hampered the new nation’s ability to pay its outstanding debts from the Revolutionary War .

In May 1787, 55 delegates gathered in Philadelphia to address the deficiencies of the Articles of Confederation and the problems that had arisen from this weakened central government.

A New Constitution

The document that emerged from the Constitutional Convention went far beyond amending the Articles, however. Instead, it established an entirely new system, including a robust central government divided into legislative , executive and judicial branches.

As soon as 39 delegates signed the proposed Constitution in September 1787, the document went to the states for ratification, igniting a furious debate between “Federalists,” who favored ratification of the Constitution as written, and “Antifederalists,” who opposed the Constitution and resisted giving stronger powers to the national government.

How Did Magna Carta Influence the U.S. Constitution?

The 13th‑century pact inspired the U.S. Founding Fathers as they wrote the documents that would shape the nation.

The Founding Fathers Feared Political Factions Would Tear the Nation Apart

The Constitution's framers viewed political parties as a necessary evil.

Checks and Balances

Separation of Powers The idea that a just and fair government must divide power between various branches did not originate at the Constitutional Convention, but has deep philosophical and historical roots. In his analysis of the government of Ancient Rome, the Greek statesman and historian Polybius identified it as a “mixed” regime with three branches: […]

The Rise of Publius

In New York, opposition to the Constitution was particularly strong, and ratification was seen as particularly important. Immediately after the document was adopted, Antifederalists began publishing articles in the press criticizing it.

They argued that the document gave Congress excessive powers and that it could lead to the American people losing the hard-won liberties they had fought for and won in the Revolution.

In response to such critiques, the New York lawyer and statesman Alexander Hamilton, who had served as a delegate to the Constitutional Convention, decided to write a comprehensive series of essays defending the Constitution, and promoting its ratification.

Who Wrote the Federalist Papers?

As a collaborator, Hamilton recruited his fellow New Yorker John Jay, who had helped negotiate the treaty ending the war with Britain and served as secretary of foreign affairs under the Articles of Confederation. The two later enlisted the help of James Madison, another delegate to the Constitutional Convention who was in New York at the time serving in the Confederation Congress.

To avoid opening himself and Madison to charges of betraying the Convention’s confidentiality, Hamilton chose the pen name “Publius,” after a general who had helped found the Roman Republic. He wrote the first essay, which appeared in the Independent Journal, on October 27, 1787.

In it, Hamilton argued that the debate facing the nation was not only over ratification of the proposed Constitution, but over the question of “whether societies of men are really capable or not of establishing good government from reflection and choice, or whether they are forever destined to depend for their political constitutions on accident and force.”

After writing the next four essays on the failures of the Articles of Confederation in the realm of foreign affairs, Jay had to drop out of the project due to an attack of rheumatism; he would write only one more essay in the series. Madison wrote a total of 29 essays, while Hamilton wrote a staggering 51.

Federalist Papers Summary

In the Federalist Papers, Hamilton, Jay and Madison argued that the decentralization of power that existed under the Articles of Confederation prevented the new nation from becoming strong enough to compete on the world stage or to quell internal insurrections such as Shays’s Rebellion .

In addition to laying out the many ways in which they believed the Articles of Confederation didn’t work, Hamilton, Jay and Madison used the Federalist essays to explain key provisions of the proposed Constitution, as well as the nature of the republican form of government.

'Federalist 10'

In Federalist 10 , which became the most influential of all the essays, Madison argued against the French political philosopher Montesquieu ’s assertion that true democracy—including Montesquieu’s concept of the separation of powers—was feasible only for small states.

A larger republic, Madison suggested, could more easily balance the competing interests of the different factions or groups (or political parties ) within it. “Extend the sphere, and you take in a greater variety of parties and interests,” he wrote. “[Y]ou make it less probable that a majority of the whole will have a common motive to invade the rights of other citizens[.]”

After emphasizing the central government’s weakness in law enforcement under the Articles of Confederation in Federalist 21-22 , Hamilton dove into a comprehensive defense of the proposed Constitution in the next 14 essays, devoting seven of them to the importance of the government’s power of taxation.

Madison followed with 20 essays devoted to the structure of the new government, including the need for checks and balances between the different powers.

'Federalist 51'

“If men were angels, no government would be necessary,” Madison wrote memorably in Federalist 51 . “If angels were to govern men, neither external nor internal controls on government would be necessary.”

After Jay contributed one more essay on the powers of the Senate , Hamilton concluded the Federalist essays with 21 installments exploring the powers held by the three branches of government—legislative, executive and judiciary.

Impact of the Federalist Papers

Despite their outsized influence in the years to come, and their importance today as touchstones for understanding the Constitution and the founding principles of the U.S. government, the essays published as The Federalist in 1788 saw limited circulation outside of New York at the time they were written. They also fell short of convincing many New York voters, who sent far more Antifederalists than Federalists to the state ratification convention.

Still, in July 1788, a slim majority of New York delegates voted in favor of the Constitution, on the condition that amendments would be added securing certain additional rights. Though Hamilton had opposed this (writing in Federalist 84 that such a bill was unnecessary and could even be harmful) Madison himself would draft the Bill of Rights in 1789, while serving as a representative in the nation’s first Congress.

HISTORY Vault: The American Revolution

Stream American Revolution documentaries and your favorite HISTORY series, commercial-free.

Ron Chernow, Hamilton (Penguin, 2004). Pauline Maier, Ratification: The People Debate the Constitution, 1787-1788 (Simon & Schuster, 2010). “If Men Were Angels: Teaching the Constitution with the Federalist Papers.” Constitutional Rights Foundation . Dan T. Coenen, “Fifteen Curious Facts About the Federalist Papers.” University of Georgia School of Law , April 1, 2007.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

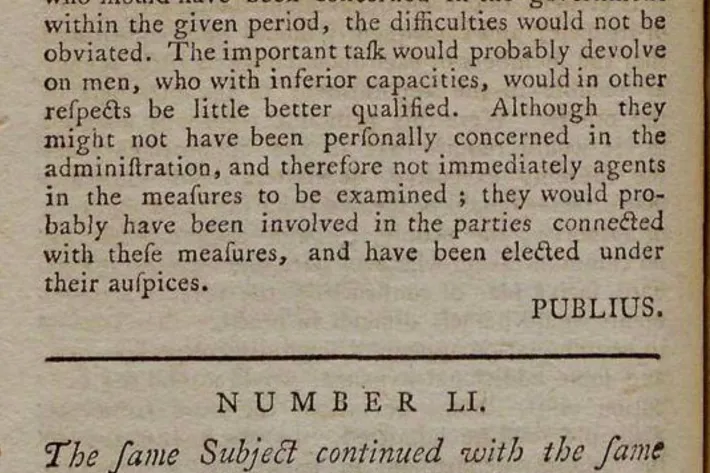

Federalist No. 51, 1788

The Federalist: A Collection of Essays, Written in Favour of the New Constitution, 1788 (The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History)

The Federalist , often called The Federalist Papers, is a series of 85 essays written by Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, and James Madison between October 1787 and May 1788. The essays were published anonymously, under the pen name “Publius,” primarily in two New York State newspapers: the New York Packet and the Independent Journal . The main purpose of the series was to urge the citizens of New York to support ratification of the proposed US Constitution. Significantly, the essays explain particular provisions of the Constitution in detail. It is for this reason, and because Hamilton and Madison were members of the Constitutional Convention, that the Federalist Papers are often used to help modern readers understand the intentions of those who drafted the Constitution. Federalist No. 51 was written by James Madison and published in February 1788. This essay addresses the need for checks and balances and advocates a separation of powers, suggesting that the government be divided into separate branches.

Federalist No. 51, February 8, 1788

The same Subject continued with the same View, and concluded

TO WHAT expedient, then, shall we finally resort for maintaining in practice the necessary partition of power among the several departments, as laid down in the constitution? The only answer that can be given is, that as all these exterior provisions are found to be inadequate, the defect must be supplied, by so contriving the interior structure of the government as that its several constituent parts may, by their mutual relations, be the means of keeping each other in their proper places. Without presuming to undertake a full development of this important idea, I will hazard a few general observations, which may perhaps place it in a clearer light, and enable us to form a more correct judgment of the principles and structure of the government planned by the convention.

In order to lay a due foundation for that separate and distinct exercise of the different powers of government, which to a certain extent, is admitted on all hands to be essential to the preservation of liberty, it is evident that each department should have a will of its own; and consequently should be so constituted that the members of each should have as little agency as possible in the appointment of the members of the others. Were this principle rigorously adhered to, it would require that all the appointments for the supreme executive, legislative, and judiciary magistracies should be drawn from the same fountain of authority, the people, through channels, having no communication whatever with one another. Perhaps such a plan of constructing the several departments would be less difficult in practice than it may in contemplation appear. Some difficulties, however, and some additional expense would attend the execution of it. Some deviations, therefore from the principle must be admitted. In the constitution of the judiciary department in particular, it might be inexpedient to insist rigorously on the principle; first, because peculiar qualifications being essential in the members, the primary consideration ought to be to select that mode of choice, which best secures these qualifications; secondly, because the permanent tenure by which the appointments are held in that department, must soon destroy all sense of dependence on the authority conferring them.

It is equally evident that the members of each department should be as little dependent as possible on those of the others, for the emoluments annexed to their offices. Were the executive magistrate, or the judges, not independent of the legislature in this particular, their independence in every other, would be merely nominal. But the great security against a gradual concentration of the several powers in the same department, consists in giving to those who administer each department, the necessary constitutional means, and personal motives, to resist encroachments of the others. The provision for defense must in this, as in all other cases, be made commensurate to the danger of attack. Ambition must be made to counteract ambition. The interest of the man must be connected with the constitutional rights of the place. It may be a reflection on human nature, that such devices should be necessary to control the abuses of government. But what is government itself, but the greatest of all reflections on human nature? If men were angels, no government would be necessary. If angels were to govern men, neither external nor internal controls on government would be necessary. In framing a government which is to be administered by men over men, the great difficulty lies in this: you must first enable the government to control the governed; and in the next place oblige it to control itself.

A dependence on the people is, no doubt, the primary control on the government; but experience has taught mankind the necessity of auxiliary precautions. This policy of supplying by opposite and rival interests, the defect of better motives, might be traced through the whole system of human affairs, private as well as public. We see it particularly displayed in all the subordinate distributions of power; where the constant aim is to divide and arrange the several offices in such a manner as that each may be a check on the other that the private interest of every individual may be a sentinel over the public rights. These inventions of prudence cannot be less requisite in the distribution of the supreme powers of the State. But it is not possible to give to each department an equal power of self-defense. In republican government, the legislative authority necessarily predominates. The remedy for this inconveniency is, to divide the legislature into different branches; and to render them by different modes of election and different principles of action, as little connected with each other, as the nature of their common functions, and their common dependence on the society, will admit. It may even be necessary to guard against dangerous encroachments by still further precautions. As the weight of the legislative authority requires that it should be thus divided, the weakness of the executive may require, on the other hand, that it should be fortified.

An absolute negative, on the legislature, appears at first view to be the natural defense with which the executive magistrate should be armed. But perhaps it would be neither altogether safe, nor alone sufficient. On ordinary occasions, it might not be exerted with the requisite firmness; and on extraordinary occasions it might be perfidiously abused. May not this defect of an absolute negative be supplied by some qualified connection between this weaker department, and the weaker branch of the stronger department, by which the latter may be led to support the constitutional rights of the former, without being too much detached from the rights of its own department? If the principles on which these observations are founded be just, as I persuade myself they are, and they be applied as a criterion to the several state constitutions, and to the federal constitution it will be found that if the latter does not perfectly correspond with them, the former are infinitely less able to bear such a test.

There are, moreover, two considerations particularly applicable to the federal system of America, which place that system in a very interesting point of view. First. In a single republic, all the power surrendered by the people, is submitted to the administration of a single government; and the usurpations are guarded against by a division of the government into distinct and separate departments. In the compound republic of America, the power surrendered by the people is first divided between two distinct governments, and then the portion allotted to each subdivided among distinct and separate departments. Hence a double security arises to the rights of the people. The different governments will control each other, at the same time that each will be controlled by itself. Second. It is of great importance in a republic, not only to guard the society against the oppression of its rulers; but to guard one part of the society against the injustice of the other part. Different interests necessarily exist in different classes of citizens. If a majority be united by a common interest, the rights of the minority will be insecure.

There are but two methods of providing against this evil: The one by creating a will in the community independent of the majority, that is, of the society itself; the other, by comprehending in the society so many separate descriptions of citizens, as will render an unjust combination of a majority of the whole very improbable, if not impracticable. The first method prevails in all governments possessing an hereditary or self-appointed authority. This at best is but a precarious security; because a power independent of the society may as well espouse the unjust views of the major, as the rightful interests of the minor party, and may possibly be turned against both parties. The second method will be exemplified in the federal republic of the United States. Whilst all authority in it will be derived from, and dependent on the society, the society itself will be broken into so many parts, interests, and classes of citizens, that the rights of individuals, or of the minority, will be in little danger from interested combinations of the majority.

In a free government the security for civil rights must be the same as that for religious rights. It consists in the one case in the multiplicity of interests, and in the other, in the multiplicity of sects. The degree of security in both cases will depend on the number of interests and sects; and this may be presumed to depend on the extent of country and number of people comprehended under the same government. This view of the subject must particularly recommend a proper federal system to all the sincere and considerate friends of republican government; Since it shows that in exact proportion as the territory of the union may be formed into more circumscribed confederacies, or states, oppressive combinations of a majority will be facilitated, the best security under the republican forms, for the rights of every class of citizens, will be diminished; and consequently, the stability and independence of some member of the government, the only other security must be proportionately increased. Justice is the end of government. It is the end of civil society. It ever has been, and ever will be pursued, until it be obtained, or until liberty be lost in the pursuit. In a society under the forms of which the stronger faction can readily unite and oppress the weaker, anarchy may as truly be said to reign, as in a state of nature where the weaker individual is not secured against the violence of the stronger; And as in the latter state, even the stronger individuals are prompted, by the uncertainty of their condition, to submit to a government which may protect the weak as well as themselves; so, in the former state, will the more powerful factions or parties be gradually induced, by a like motive, to wish for a government which will protect all parties, the weaker as well as the more powerful.

It can be little doubted that if the State of Rhode Island was separated from the confederacy, and left to itself, the insecurity of rights under the popular form of government within such narrow limits, would be displayed by such reiterated oppressions of factious majorities, that some power altogether independent of the people would soon be called for by the voice of the very factions whose misrule had proved the necessity of it. In the extended republic of the United States, and among the great variety of interests, parties, and sects which it embraces, a coalition of a majority of the whole society could seldom take place on any other principles than those of justice and the general good: Whilst there being thus less danger to a minor from the will of a major party, there must be less pretext, also, to provide for the security of the former, by introducing into the government a will not dependent on the latter; or in other words, a will independent of the society itself. It is no less certain than it is important, notwithstanding the contrary opinions which have been entertained, that the larger the society, provided it lie within a practicable sphere, the more duly capable it will be of self-government. And happily for the republican cause, the practicable sphere may be carried to a very great extent, by a judicious modification and mixture of the federal principle.

Source: James Madison, “Federalist No. 51,” The Federalist , New York, 1788, The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, GLC01551.

The Federalist Papers

The Federalist Papers are a series of 85 essays arguing in support of the United States Constitution . Alexander Hamilton , James Madison , and John Jay were the authors behind the pieces, and the three men wrote collectively under the name of Publius .

Seventy-seven of the essays were published as a series in The Independent Journal , The New York Packet , and The Daily Advertiser between October of 1787 and August 1788. They weren't originally known as the "Federalist Papers," but just "The Federalist." The final 8 were added in after.

At the time of publication, the authorship of the articles was a closely guarded secret. It wasn't until Hamilton's death in 1804 that a list crediting him as one of the authors became public. It claimed fully two-thirds of the essays for Hamilton. Many of these would be disputed by Madison later on, who had actually written a few of the articles attributed to Hamilton.

Once the Federal Convention sent the Constitution to the Confederation Congress in 1787, the document became the target of criticism from its opponents. Hamilton, a firm believer in the Constitution, wrote in Federalist No. 1 that the series would "endeavor to give a satisfactory answer to all the objections which shall have made their appearance, that may seem to have any claim to your attention."

Alexander Hamilton was the force behind the project, and was responsible for recruiting James Madison and John Jay to write with him as Publius. Two others were considered, Gouverneur Morris and William Duer . Morris rejected the offer, and Hamilton didn't like Duer's work. Even still, Duer managed to publish three articles in defense of the Constitution under the name Philo-Publius , or "Friend of Publius."

Hamilton chose "Publius" as the pseudonym under which the series would be written, in honor of the great Roman Publius Valerius Publicola . The original Publius is credited with being instrumental in the founding of the Roman Republic. Hamilton thought he would be again with the founding of the American Republic. He turned out to be right.

John Jay was the author of five of the Federalist Papers. He would later serve as Chief Justice of the United States. Jay became ill after only contributed 4 essays, and was only able to write one more before the end of the project, which explains the large gap in time between them.

Jay's Contributions were Federalist: No. 2 , No. 3 , No. 4 , No. 5 , and No. 64 .

James Madison , Hamilton's major collaborator, later President of the United States and "Father of the Constitution." He wrote 29 of the Federalist Papers, although Madison himself, and many others since then, asserted that he had written more. A known error in Hamilton's list is that he incorrectly ascribed No. 54 to John Jay, when in fact Jay wrote No. 64 , has provided some evidence for Madison's suggestion. Nearly all of the statistical studies show that the disputed papers were written by Madison, but as the writers themselves released no complete list, no one will ever know for sure.

Opposition to the Bill of Rights

The Federalist Papers, specifically Federalist No. 84 , are notable for their opposition to what later became the United States Bill of Rights . Hamilton didn't support the addition of a Bill of Rights because he believed that the Constitution wasn't written to limit the people. It listed the powers of the government and left all that remained to the states and the people. Of course, this sentiment wasn't universal, and the United States not only got a Constitution, but a Bill of Rights too.

No. 1: General Introduction Written by: Alexander Hamilton October 27, 1787

No.2: Concerning Dangers from Foreign Force and Influence Written by: John Jay October 31, 1787

No. 3: The Same Subject Continued: Concerning Dangers from Foreign Force and Influence Written by: John Jay November 3, 1787

No. 4: The Same Subject Continued: Concerning Dangers from Foreign Force and Influence Written by: John Jay November 7, 1787

No. 5: The Same Subject Continued: Concerning Dangers from Foreign Force and Influence Written by: John Jay November 10, 1787

No. 6:Concerning Dangers from Dissensions Between the States Written by: Alexander Hamilton November 14, 1787

No. 7 The Same Subject Continued: Concerning Dangers from Dissensions Between the States Written by: Alexander Hamilton November 15, 1787

No. 8: The Consequences of Hostilities Between the States Written by: Alexander Hamilton November 20, 1787

No. 9 The Union as a Safeguard Against Domestic Faction and Insurrection Written by: Alexander Hamilton November 21, 1787

No. 10 The Same Subject Continued: The Union as a Safeguard Against Domestic Faction and Insurrection Written by: James Madison November 22, 1787

No. 11 The Utility of the Union in Respect to Commercial Relations and a Navy Written by: Alexander Hamilton November 24, 1787

No 12: The Utility of the Union In Respect to Revenue Written by: Alexander Hamilton November 27, 1787

No. 13: Advantage of the Union in Respect to Economy in Government Written by: Alexander Hamilton November 28, 1787

No. 14: Objections to the Proposed Constitution From Extent of Territory Answered Written by: James Madison November 30, 1787

No 15: The Insufficiency of the Present Confederation to Preserve the Union Written by: Alexander Hamilton December 1, 1787

No. 16: The Same Subject Continued: The Insufficiency of the Present Confederation to Preserve the Union Written by: Alexander Hamilton December 4, 1787

No. 17: The Same Subject Continued: The Insufficiency of the Present Confederation to Preserve the Union Written by: Alexander Hamilton December 5, 1787

No. 18: The Same Subject Continued: The Insufficiency of the Present Confederation to Preserve the Union Written by: James Madison December 7, 1787

No. 19: The Same Subject Continued: The Insufficiency of the Present Confederation to Preserve the Union Written by: James Madison December 8, 1787

No. 20: The Same Subject Continued: The Insufficiency of the Present Confederation to Preserve the Union Written by: James Madison December 11, 1787

No. 21: Other Defects of the Present Confederation Written by: Alexander Hamilton December 12, 1787

No. 22: The Same Subject Continued: Other Defects of the Present Confederation Written by: Alexander Hamilton December 14, 1787

No. 23: The Necessity of a Government as Energetic as the One Proposed to the Preservation of the Union Written by: Alexander Hamilton December 18, 1787

No. 24: The Powers Necessary to the Common Defense Further Considered Written by: Alexander Hamilton December 19, 1787

No. 25: The Same Subject Continued: The Powers Necessary to the Common Defense Further Considered Written by: Alexander Hamilton December 21, 1787

No. 26: The Idea of Restraining the Legislative Authority in Regard to the Common Defense Considered Written by: Alexander Hamilton December 22, 1787

No. 27: The Same Subject Continued: The Idea of Restraining the Legislative Authority in Regard to the Common Defense Considered Written by: Alexander Hamilton December 25, 1787

No. 28: The Same Subject Continued: The Idea of Restraining the Legislative Authority in Regard to the Common Defense Considered Written by: Alexander Hamilton December 26, 1787

No. 29: Concerning the Militia Written by: Alexander Hamilton January 9, 1788

No. 30: Concerning the General Power of Taxation Written by: Alexander Hamilton December 28, 1787

No. 31: The Same Subject Continued: Concerning the General Power of Taxation Written by: Alexander Hamilton January 1, 1788

No. 32: The Same Subject Continued: Concerning the General Power of Taxation Written by: Alexander Hamilton January 2, 1788

No. 33: The Same Subject Continued: Concerning the General Power of Taxation Written by: Alexander Hamilton January 2, 1788

No. 34: The Same Subject Continued: Concerning the General Power of Taxation Written by: Alexander Hamilton January 5, 1788

No. 35: The Same Subject Continued: Concerning the General Power of Taxation Written by: Alexander Hamilton January 5, 1788

No. 36: The Same Subject Continued: Concerning the General Power of Taxation Written by: Alexander Hamilton January 8, 1788

No. 37: Concerning the Difficulties of the Convention in Devising a Proper Form of Government Written by: Alexander Hamilton January 11, 1788

No. 38: The Same Subject Continued, and the Incoherence of the Objections to the New Plan Exposed Written by: James Madison January 12, 1788

No. 39: The Conformity of the Plan to Republican Principles Written by: James Madison January 18, 1788

No. 40: The Powers of the Convention to Form a Mixed Government Examined and Sustained Written by: James Madison January 18, 1788

No. 41: General View of the Powers Conferred by the Constitution Written by: James Madison January 19, 1788

No. 42: The Powers Conferred by the Constitution Further Considered Written by: James Madison January 22, 1788

No. 43: The Same Subject Continued: The Powers Conferred by the Constitution Further Considered Written by: James Madison January 23, 1788

No. 44: Restrictions on the Authority of the Several States Written by: James Madison January 25, 1788

No. 45: The Alleged Danger From the Powers of the Union to the State Governments Considered Written by: James Madison January 26, 1788

No. 46: The Influence of the State and Federal Governments Compared Written by: James Madison January 29, 1788

No. 47: The Particular Structure of the New Government and the Distribution of Power Among Its Different Parts Written by: James Madison January 30, 1788

No. 48: These Departments Should Not Be So Far Separated as to Have No Constitutional Control Over Each Other Written by: James Madison February 1, 1788

No. 49: Method of Guarding Against the Encroachments of Any One Department of Government Written by: James Madison February 2, 1788

No. 50: Periodic Appeals to the People Considered Written by: James Madison February 5, 1788

No. 51: The Structure of the Government Must Furnish the Proper Checks and Balances Between the Different Departments Written by: James Madison February 6, 1788

No. 52: The House of Representatives Written by: James Madison February 8, 1788

No. 53: The Same Subject Continued: The House of Representatives Written by: James Madison February 9, 1788

No. 54: The Apportionment of Members Among the States Written by: James Madison February 12, 1788

No. 55: The Total Number of the House of Representatives Written by: James Madison February 13, 1788

No. 56: The Same Subject Continued: The Total Number of the House of Representatives Written by: James Madison February 16, 1788

No. 57: The Alleged Tendency of the New Plan to Elevate the Few at the Expense of the Many Written by: James Madison February 19, 1788

No. 58: Objection That The Number of Members Will Not Be Augmented as the Progress of Population Demands Considered Written by: James Madison February 20, 1788

No. 59: Concerning the Power of Congress to Regulate the Election of Members Written by: Alexander Hamilton February 22, 1788

No. 60: The Same Subject Continued: Concerning the Power of Congress to Regulate the Election of Members Written by: Alexander Hamilton February 23, 1788

No. 61: The Same Subject Continued: Concerning the Power of Congress to Regulate the Election of Members Written by: Alexander Hamilton February 26, 1788

No. 62: The Senate Written by: James Madison February 27, 1788

No. 63: The Senate Continued Written by: James Madison March 1, 1788

No. 64: The Powers of the Senate Written by: John Jay March 5, 1788

No. 65: The Powers of the Senate Continued Written by: Alexander Hamilton March 7, 1788

No. 66: Objections to the Power of the Senate To Set as a Court for Impeachments Further Considered Written by: Alexander Hamilton March 8, 1788

No. 67: The Executive Department Written by: Alexander Hamilton March 11, 1788

No. 68: The Mode of Electing the President Written by: Alexander Hamilton March 12, 1788

No. 69: The Real Character of the Executive Written by: Alexander Hamilton March 14, 1788

No. 70: The Executive Department Further Considered Written by: Alexander Hamilton March 15, 1788

No. 71: The Duration in Office of the Executive Written by: Alexander Hamilton March 18, 1788

No. 72: The Same Subject Continued, and Re-Eligibility of the Executive Considered Written by: Alexander Hamilton March 19, 1788

No. 73: The Provision For The Support of the Executive, and the Veto Power Written by: Alexander Hamilton March 21, 1788

No. 74: The Command of the Military and Naval Forces, and the Pardoning Power of the Executive Written by: Alexander Hamilton March 25, 1788

No. 75: The Treaty Making Power of the Executive Written by: Alexander Hamilton March 26, 1788

No. 76: The Appointing Power of the Executive Written by: Alexander Hamilton April 1, 1788

No. 77: The Appointing Power Continued and Other Powers of the Executive Considered Written by: Alexander Hamilton April 2, 1788

No. 78: The Judiciary Department Written by: Alexander Hamilton June 14, 1788

No. 79: The Judiciary Continued Written by: Alexander Hamilton June 18, 1788

No. 80: The Powers of the Judiciary Written by: Alexander Hamilton June 21, 1788

No. 81: The Judiciary Continued, and the Distribution of the Judicial Authority Written by: Alexander Hamilton June 25, 1788

No. 82: The Judiciary Continued Written by: Alexander Hamilton July 2, 1788

No. 83: The Judiciary Continued in Relation to Trial by Jury Written by: Alexander Hamilton July 5, 1788

No. 84: Certain General and Miscellaneous Objections to the Constitution Considered and Answered Written by: Alexander Hamilton July 16, 1788

No. 85: Concluding Remarks Written by: Alexander Hamilton August 13, 1788

Images courtesy of Wikimedia Commons, licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-Share-Alike License 3.0.

© Oak Hill Publishing Company. All rights reserved. Oak Hill Publishing Company. Box 6473, Naperville, IL 60567 For questions or comments about this site please email us at [email protected]

Plan Your Visit

- Things to Do

- Where to Eat

- Hours & Directions

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Accessibility

- Washington, D.C. Metro Area

- Guest Policies

- Historic Area

- Distillery & Gristmill

- Virtual Tour

George Washington

- French & Indian War

- Revolutionary War

- Constitution

- First President

- Martha Washington

- Native Americans

Preservation

- Collections

- Archaeology

- Architecture

- The Mount Vernon Ladies' Association

- Restoration Projects

- Preserving the View

- Preservation Timeline

- For Teachers

- Primary Source Collections

- Secondary Sources

- Educational Events

- Interactive Tools

- Videos and Podcasts

Washington Library

- Catalogs and Digital Resources

- Research Fellowships

- The Papers of George Washington

- Library Events & Programs

- Leadership Institute

- Center for Digital History

- George Washington Prize

- About the Library

- Back to Main menu

- Colonial Music Institute

- Past Projects

- Digital Exhibits

- Digital Encyclopedia

- About the Encyclopedia

- Contributors

- George Washington Presidential Library

Estate Hours

9 a.m. to 4 p.m.

u_turn_left Directions & Parking

Federalist Papers

George Washington was sent draft versions of the first seven essays on November 18, 1787 by James Madison, who revealed to Washington that he was one of the anonymous writers. Washington agreed to secretly transmit the drafts to his in-law David Stuart in Richmond, Virginia so the essays could be more widely published and distributed. Washington explained in a letter to David Humphreys that the ratification of the Constitution would depend heavily "on literary abilities, & the recommendation of it by good pens," and his efforts to proliferate the Federalist Papers reflected this feeling. 1

Washington was skeptical of Constitutional opponents, known as Anti-Federalists, believing that they were either misguided or seeking personal gain. He believed strongly in the goals of the Constitution and saw The Federalist Papers and similar publications as crucial to the process of bolstering support for its ratification. Washington described such publications as "have thrown new lights upon the science of Government, they have given the rights of man a full and fair discussion, and have explained them in so clear and forcible a manner as cannot fail to make a lasting impression upon those who read the best publications of the subject, and particularly the pieces under the signature of Publius." 2

Although Washington made few direct contributions to the text of the new Constitution and never officially joined the Federalist Party, he profoundly supported the philosophy behind the Constitution and was an ardent supporter of its ratification.

The philosophical influence of the Enlightenment factored significantly in the essays, as the writers sought to establish a balance between centralized political power and individual liberty. Although the writers sought to build support for the Constitution, Madison, Hamilton, and Jay did not see their work as a treatise, per se, but rather as an on-going attempt to make sense of a new form of government.

The Federalist Paper s represented only one facet in an on-going debate about what the newly forming government in America should look like and how it would govern. Although it is uncertain precisely how much The Federalist Papers affected the ratification of the Constitution, they were considered by many at the time—and continue to be considered—one of the greatest works of American political philosophy.

Adam Meehan The University of Arizona

Notes: 1. "George Washington to David Humphreys, 10 October 1787," in George Washington, Writings , ed. John Rhodehamel (New York: Library of America, 1997), 657.

2. "George Washington to John Armstrong, 25 April 1788," in George Washington, Writings , ed. John Rhodehamel (New York: Library of America, 1997), 672.

Bibliography: Chernow, Ron. Washington: A Life . New York: Penguin, 2010.

Epstein, David F. The Political Theory of The Federalist . Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1984.

Furtwangler, Albert. The Authority of Publius: A Reading of the Federalist Papers . Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1984.

George Washington, Writings , ed. John Rhodehamel. New York: Library of America, 1997.

The Federalist Papers (1787-1788)

Federalist papers.

After the Constitution was completed during the summer of 1787, the work of ratifying it (or approving it) began. As the Constitution itself required, 3/4ths of the states would have to approve the new Constitution before it would go into effect for those ratifying states.

The Constitution granted the national government more power than under the Articles of Confederation . Many Americans were concerned that the national government with its new powers, as well as the new division of power between the central and state governments, would threaten liberty.

What are the Federalist Papers?

In order to help convince their fellow Americans of their view that the Constitution would not threaten freedom, Federalist Paper authors, James Madison , Alexander Hamilton , and John Jay teamed up in 1788 to write a series of essays in defense of the Constitution. The essays, which appeared in newspapers addressed to the people of the state of New York, are known as the Federalist Papers. They are regarded as one of the most authoritative sources on the meaning of the Constitution, including constitutional principles such as checks and balances, federalism, and separation of powers.

Federalist Papers Collection

Federalist and anti-federalist playlist, related resources.

Would you have been a Federalist or an Anti-Federalist?

Federalist or Anti-Federalist? Over the next few months we will explore through a series of eLessons the debate over ratification of the United States Constitution as discussed in the Federalist and Anti-Federalist papers. We look forward to exploring this important debate with you! One of the great debates in American history was over the ratification […]

Federalist No. 1 Excerpts Annotated

Federalist 10

Written by James Madison, this essay defended the form of republican government proposed by the Constitution. Critics of the Constitution argued that the proposed federal government was too large and would be unresponsive to the people.

Primary Source: Federalist No. 26

Primary Source: Federalist No. 33

Handout E: Excerpts from Federalist No. 39, James Madison (1788)

Primary Source: Excerpts from Federalist No. 44

Handout B: Excerpts from Federalist No 10, 51, 55, and 57

Handout I: Excerpts of Federalist No. 57

Primary Source: Federalist No. 39

Primary Source: Madison – Excerpts from Federalist No. 47 (1788)

Federalist 51

In this Federalist Paper, James Madison explains and defends the checks and balances system in the Constitution. Each branch of government is framed so that its power checks the power of the other two branches; additionally, each branch of government is dependent on the people, who are the source of legitimate authority.

Handout A: Excerpts from Federalist No 62

Primary Source: Excerpts from Federalist No. 63

Federalist 70

In this Federalist Paper, Alexander Hamilton argues for a strong executive leader, as provided for by the Constitution, as opposed to the weak executive under the Articles of Confederation. He asserts, “energy in the executive is the leading character in the definition of good government.

Primary Source: Federalist No. 78 Excerpts Annotated

Primary Source: Federalist No. 84 Excerpts Annotated

U.S. Constitution.net

Federalist papers and the constitution.

During the late 1780s, the United States faced significant challenges with its initial governing framework, the Articles of Confederation. These issues prompted the creation of the Federalist Papers, a series of essays aimed at advocating for a stronger central government under the newly proposed Constitution. This article will examine the purpose, key arguments, and lasting impact of these influential writings.

Background and Purpose of the Federalist Papers

The Articles of Confederation, though a pioneer effort, left Congress without the power to tax or regulate interstate commerce, making it difficult to pay off Revolutionary War debts and curb internal squabbles among states.

In May 1787, America's brightest political minds convened in Philadelphia and created the Constitution—a document establishing a robust central government with legislative, executive, and judicial branches. However, before it could take effect, the Constitution needed ratification from nine of the thirteen states, facing opposition from critics known as Anti-Federalists.

The Federalist Papers, a series of 85 essays written by Alexander Hamilton , James Madison , and John Jay under the pseudonym "Publius," aimed to calm fears and win support for the Constitution. Hamilton initiated the project, recruiting Madison and Jay to contribute. Madison drafted substantial portions of the Constitution and provided detailed defenses, while Jay, despite health issues, also contributed essays.

The Federalist Papers systematically dismantled the opposition's arguments and explained the Constitution's provisions in detail. They gained national attention, were reprinted in newspapers across the country, and eventually collated into two volumes for broader distribution.

Hamilton emphasized the necessity of a central authority with the power to tax and enforce laws, citing specific failures under the Articles like the inability to generate revenue or maintain public order. Jay addressed the need for unity and the inadequacies of confederation in foreign diplomacy.

The Federalist Papers provided the framework needed to understand and eventually ratify the Constitution, remaining essential reading for anyone interested in the foundations of the American political system.

Key Arguments in the Federalist Papers

Among the key arguments presented in the Federalist Papers, three themes stand out:

- The need for a stronger central government

- The importance of checks and balances

- The dangers of factionalism

Federalist No. 23 , written by Alexander Hamilton, argued for a robust central government, citing the weaknesses of the Articles of Confederation. Hamilton contended that empowering the central government with the means to enforce laws and collect taxes was essential for the Union's survival and prosperity.

In Federalist No. 51 , James Madison addressed the principle of checks and balances, arguing that the structure of the new government would prevent any single branch from usurping unrestrained power. Each branch—executive, legislative, and judicial—would have the means and motivation to check the power of the others, safeguarding liberty.

Federalist No. 10 , also by Madison, delved into the dangers posed by factions—groups united by a common interest adverse to the rights of others or the interests of the community. Madison acknowledged that factions are inherent within any free society and cannot be eliminated without destroying liberty. He argued that a well-constructed Union would break and control the violence of faction by filtering their influence through a large republic.

Hamilton's Federalist No. 78 brought the concept of judicial review to the forefront, establishing the judiciary as a guardian of the Constitution and essential for interpreting laws and checking the actions of the legislature and executive branches. 1

The Federalist Papers meticulously dismantled Anti-Federalist criticisms and showcased how the proposed system would create a stable and balanced government capable of both governing effectively and protecting individual rights. These essays remain seminal works for understanding the underpinnings of the United States Constitution and the brilliance of the Founding Fathers.

Analysis of Federalist 10 and Federalist 51

Federalist 10 and Federalist 51 are two of the most influential essays within the Federalist Papers, elucidating fundamental principles that continue to support the American political system. They were carefully crafted to address the concerns of Anti-Federalists who feared that the new Constitution might pave the way for tyranny and undermine individual liberties.

In Federalist 10 , James Madison addresses the inherent dangers posed by factions. He argues that a large republic is the best defense against their menace, as it becomes increasingly challenging for any single faction to dominate in a sprawling and diverse nation. The proposed Constitution provides a systemic safeguard against factionalism by implementing a representative form of government, where elected representatives act as a filtering mechanism.

Federalist 51 further elaborates on how the structure of the new government ensures the protection of individual rights through a system of checks and balances. Madison supports the division of government into three coequal branches, each equipped with sufficient autonomy and authority to check the others. He asserts that ambition must be made to counteract ambition, emphasizing that the self-interest of individuals within each branch would serve as a natural check on the others. 2

Madison also delves into the need for a bicameral legislature, comprising the House of Representatives and the Senate. This dual structure aims to balance the demands of the majority with the necessity of protecting minority rights, thereby preventing majoritarian tyranny.

Together, Federalist 10 and Federalist 51 form a comprehensive blueprint for a resilient and balanced government. Madison's insights address both the internal and external mechanisms necessary to guard against tyranny and preserve individual liberties. These essays speak to the enduring principles that have guided the American republic since its inception, proving the timeless wisdom of the Founding Fathers and the genius of the American Constitution.

Impact and Legacy of the Federalist Papers

The Federalist Papers had an immediate and profound impact on the ratification debates, particularly in New York, where opposition to the Constitution was fierce and vocal. Alexander Hamilton, a native of New York, understood the weight of these objections and recognized that New York's support was crucial for the Constitution's success, given the state's economic influence and strategic location. The essays were carefully crafted to address New Yorkers' specific concerns and to persuade undecided delegates.

The comprehensive detail and logical rigor of the Federalist Papers succeeded in swaying public opinion. They systematically addressed Anti-Federalist critiques, such as the fear that a strong central government would trample individual liberties. Hamilton, Madison, and Jay argued for the necessity of a powerful, yet balanced federal system, capable of uniting the states and ensuring both national security and economic stability.

In New York, the Federalist essays began appearing in newspapers in late 1787 and continued into 1788. Despite opposition, especially from influential Anti-Federalists like Governor George Clinton, the arguments laid out by "Publius" played a critical role in turning the tide. They provided Federalists with a potent arsenal of arguments to counter Anti-Federalists at the state's ratification convention. When the time came to vote, the persuasive power of the essays contributed significantly to New York's eventual decision to ratify the Constitution by a narrow margin.

The impact of the Federalist Papers extends far beyond New York. They influenced debates across the fledgling nation, helping to build momentum towards the required nine-state ratification. Their detailed exposition of the Constitution's provisions and the philosophic principles underlying them offered critical insights for citizens and delegates in other states. The essays became indispensable tools in the broader national dialogue about what kind of government the United States should have, guiding the country towards ratification.

The long-term significance of the Federalist Papers in American political thought and constitutional interpretation is substantial. Over the centuries, they have become foundational texts for understanding the intentions of the Framers. Jurists, scholars, and lawmakers have turned to these essays for guidance on interpreting the Constitution's provisions, shaping American constitutional law. Judges, including the justices of the Supreme Court, have frequently cited these essays in landmark rulings to elucidate the Framers' intent.

The Federalist Papers have profoundly influenced the development of American political theory, contributing to discussions about federalism, republicanism, and the balance between liberty and order. Madison's arguments in Federalist No. 10 have become keystones in the study of pluralism and the mechanisms by which diverse interests can coexist within a unified political system.

The essays laid the groundwork for ongoing debates about the role of the federal government, the balance of power among its branches, and the preservation of individual liberties. They provided intellectual support for later expansions of constitutional rights through amendments and judicial interpretations.

Their legacy also includes a robust defense of judicial review and the judiciary's role as a guardian of the Constitution. Hamilton's Federalist No. 78 provided a compelling argument for judicial independence, which has been a cornerstone in maintaining the rule of law and protecting constitutional principles against transient political pressures.

The Federalist Papers were crucial in the ratification of the Constitution, particularly in the contentious atmosphere of New York's debates. Their immediate effect was to facilitate the acceptance of the new governing framework. In the long term, their meticulously argued positions have provided a lasting blueprint for constitutional interpretation, influencing American political thought and practical governance for over two centuries. The essays stand as a testament to the foresight and philosophical acumen of the Founding Fathers, continuing to illuminate the enduring principles of the United States Constitution.

Search form

- Browse All Lessons

- First Year 1L

- Upper Level 2L & 3L

- Subject Outlines

- New Lessons

- Updated Lessons

- Removed Lessons

- Browse All Books

- About our Books

- Print Books

- Permissions

- Become an Author

- Coming Soon

- Browse All Resources

- CALI Podcasts

- CALI Forums

- Online Teaching Tips & Techniques

- Webinars & Online Courses

- The 2024 CALI® Summer Challenge

- Awards Listing

- About Awards

- CALIcon - CALI Conference for Law School Computing

- Event Calendar

- Register for the CALI Tech Briefing

- CALI Spotlight Blog

- Board of Directors

- Help & FAQs

The Federalist Papers

eLangdell Editor

Description

"The Federalist, commonly referred to as the Federalist Papers, is a series of 85 essays written by Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, and James Madison between October 1787 and May 1788. The essays were published anonymously, under the pen name "Publius," in various New York state newspapers of the time.

"The Federalist Papers were written and published to urge New Yorkers to ratify the proposed United States Constitution, which was drafted in Philadelphia in the summer of 1787. In lobbying for adoption of the Constitution over the existing Articles of Confederation, the essays explain particular provisions of the Constitution in detail. For this reason, and because Hamilton and Madison were each members of the Constitutional Convention, the Federalist Papers are often used today to help interpret the intentions of those drafting the Constitution.

"The Federalist Papers were published primarily in two New York state newspapers: The New York Packet and The Independent Journal. They were reprinted in other newspapers in New York state and in several cities in other states. A bound edition, with revisions and corrections by Hamilton, was published in 1788 by printers J. and A. McLean. An edition published by printer Jacob Gideon in 1818, with revisions and corrections by Madison, was the first to identify each essay by its author's name. Because of its publishing history, the assignment of authorship, numbering, and exact wording may vary with different editions of The Federalist.

"The text of The Federalist used here was compiled for Project Gutenberg by scholars who drew on many available versions of the papers." - The Library of Congress

CALI Topics

- Legal Concepts and Skills

Collections

- Legal Classics

Federalist Papers

- Federalist 1-10

- Federalist 11-36

- Federalist 37-61

- Federalist 62-85

- America's Four Republics

- Article The First

- Feds Finally Agree

- Historic.us

Monday, December 17, 2012

Alexander hamilton - john jay - james madison.

The Federalist Papers comprise a series of 85 influential essays penned by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay, designed to advocate for the ratification of the United States Constitution. Written under the shared pseudonym "Publius," these essays were initially published serially in New York newspapers between October 1787 and August 1788. The first 77 essays appeared in The Independent Journal and The New York Packet , reaching an audience immersed in the intense debates surrounding the new Constitution’s adoption.

In 1788, publishers John and Andrew M’Lean compiled these works into a two-volume collection titled The Federalist: A Collection of Essays, Written in Favor of the New Constitution, as Agreed upon by the Federal Convention, September 17, 1787 . Printed in New York, this edition was the first to present all 85 essays collectively, solidifying the authors’ arguments and ensuring wider distribution and lasting impact.

The primary objective of The Federalist Papers was to persuade the people of New York to ratify the newly proposed Constitution. Each essay delves into specific facets of the Constitution, defending its structure and addressing concerns of the Anti-Federalists, who feared a too-powerful central government. Among the key topics discussed were:

- The Structure and Powers of the Federal Government : Advocating for a strong yet balanced federal structure, the essays outlined the Constitution’s provisions for a unified national government capable of addressing the collective needs of the states.

- The System of Checks and Balances : The authors argued that dividing government powers among separate branches would prevent any one branch from dominating, thus ensuring liberty and preventing tyranny.

- The Division of Power Between Federal and State Governments : Known as federalism, this distribution of power was presented as a means to balance national authority with states' rights, preserving local autonomy while maintaining national cohesion.

- The Protection of Individual Rights : Although the Constitution as originally proposed did not include a Bill of Rights, the essays suggested that the framework contained implicit protections for individual freedoms, which would later be solidified with the Bill of Rights.

The essays’ authorship was intentionally kept anonymous under the pseudonym "Publius" to focus attention on the arguments rather than the writers' identities. Today, however, the authorship is well-established:

- Alexander Hamilton wrote 51 essays, covering topics such as taxation, military defense, and the judiciary.

- James Madison contributed 29 essays, focusing on the theory of federalism, the need for a strong union, and the weaknesses of the Articles of Confederation.

- John Jay authored 5 essays, primarily addressing foreign affairs and the importance of a unified national government in international relations.

The Federalist Papers remain a cornerstone of American political philosophy and constitutional interpretation. They are frequently cited in legal and academic discourse, serving as a primary source for understanding the framers’ intentions and the foundational principles of American governance. These essays continue to be studied widely, providing insight into the original intent behind the Constitution and shaping discussions on its contemporary applications.

Students and Teachers of US History this is a video of Stanley and Christopher Klos presenting America's Four United Republics Curriculum at the University of Pennsylvania's Wharton School. The December 2015 video was an impromptu capture by a member of the audience of Penn students, professors and guests that numbered about 200. - Click Here for more information

Explore the Constitution

The constitution.

- Read the Full Text

Dive Deeper

Constitution 101 course.

- The Drafting Table

- Supreme Court Cases Library

- Founders' Library

- Constitutional Rights: Origins & Travels

Start your constitutional learning journey

- News & Debate Overview

- Constitution Daily Blog

- America's Town Hall Programs

- Special Projects

- Media Library

America’s Town Hall

Watch videos of recent programs.

- Education Overview

- Constitution 101 Curriculum

- Classroom Resources by Topic

- Classroom Resources Library

- Live Online Events

- Professional Learning Opportunities

- Constitution Day Resources

- Election Teaching Resources

Constitution 101 With Khan Academy

Explore our new course that empowers students to learn the constitution at their own pace..

- Explore the Museum

- Plan Your Visit

- Exhibits & Programs

- Field Trips & Group Visits

- Host Your Event

- Buy Tickets

New exhibit

The first amendment, historic document, federalist 1 (1787).

Alexander Hamilton | 1787

On October 27, 1787, Alexander Hamilton published the opening essay of The Federalist Papers — Federalist 1 . The Federalist Papers were a series of 85 essays printed in newspapers to persuade the American people (and especially Hamilton’s fellow New Yorkers) to support ratification of the new Constitution. These essays were written by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay—with all three authors writing under the pen name “Publius.” On September 17, 1787, the delegates to the Constitutional Convention had signed the new U.S. Constitution. This new Constitution was the Framers’ proposal for a new national government. But it was only that—a proposal. The Framers left the question of ratification—whether to say “yes” or “no” to the new Constitution—to the American people. In the Framers’ view, only the American people themselves had the authority to tear up the previous framework of government—the Articles of Confederation—and establish a new one. The ratification process itself embodied one of the Constitution’s core principles: popular sovereignty, or the idea that all political power is derived from the consent of “We the People.” In Federalist 1, Hamilton captured this vision well, framing the stakes of the battle over ratification. In this opening essay, Hamilton called on the American people to “deliberate on a new Constitution” and prove to the world that they were capable of choosing a government based on “reflection and choice,” not “accident and force.”

Selected by

The National Constitution Center

AFTER an unequivocal experience of the inefficiency of the subsisting federal government, you are called upon to deliberate on a new Constitution for the United States of America. The subject speaks its own importance; comprehending in its consequences nothing less than the existence of the UNION, the safety and welfare of the parts of which it is composed, the fate of an empire in many respects the most interesting in the world. It has been frequently remarked that it seems to have been reserved to the people of this country, by their conduct and example, to decide the important question, whether societies of men are really capable or not of establishing good government from reflection and choice, or whether they are forever destined to depend for their political constitutions on accident and force. If there be any truth in the remark, the crisis at which we are arrived may with propriety be regarded as the era in which that decision is to be made; and a wrong election of the part we shall act may, in this view, deserve to be considered as the general misfortune of mankind. This idea will add the inducements of philanthropy to those of patriotism, to heighten the solicitude which all considerate and good men must feel for the event. Happy will it be if our choice should be directed by a judicious estimate of our true interests, unperplexed and unbiased by considerations not connected with the public good. But this is a thing more ardently to be wished than seriously to be expected. The plan offered to our deliberations affects too many particular interests, innovates upon too many local institutions, not to involve in its discussion a variety of objects foreign to its merits, and of views, passions and prejudices little favorable to the discovery of truth.

Among the most formidable of the obstacles which the new Constitution will have to encounter may readily be distinguished the obvious interest of a certain class of men in every State to resist all changes which may hazard a diminution of the power, emolument, and consequence of the offices they hold under the State establishments; and the perverted ambition of another class of men, who will either hope to aggrandize themselves by the confusions of their country, or will flatter themselves with fairer prospects of elevation from the subdivision of the empire into several partial confederacies than from its union under one government.

It is not, however, my design to dwell upon observations of this nature. I am well aware that it would be disingenuous to resolve indiscriminately the opposition of any set of men (merely because their situations might subject them to suspicion) into interested or ambitious views. Candor will oblige us to admit that even such men may be actuated by upright intentions; and it cannot be doubted that much of the opposition which has made its appearance, or may hereafter make its appearance, will spring from sources, blameless at least, if not respectable—the honest errors of minds led astray by preconceived jealousies and fears. So numerous indeed and so powerful are the causes which serve to give a false bias to the judgment, that we, upon many occasions, see wise and good men on the wrong as well as on the right side of questions of the first magnitude to society. This circumstance, if duly attended to, would furnish a lesson of moderation to those who are ever so much persuaded of their being in the right in any controversy. And a further reason for caution, in this respect, might be drawn from the reflection that we are not always sure that those who advocate the truth are influenced by purer principles than their antagonists. Ambition, avarice, personal animosity, party opposition, and many other motives not more laudable than these, are apt to operate as well upon those who support as those who oppose the right side of a question. Were there not even these inducements to moderation, nothing could be more ill-judged than that intolerant spirit which has, at all times, characterized political parties. For in politics, as in religion, it is equally absurd to aim at making proselytes by fire and sword. Heresies in either can rarely be cured by persecution.

And yet, however just these sentiments will be allowed to be, we have already sufficient indications that it will happen in this as in all former cases of great national discussion. A torrent of angry and malignant passions will be let loose. To judge from the conduct of the opposite parties, we shall be led to conclude that they will mutually hope to evince the justness of their opinions, and to increase the number of their converts by the loudness of their declamations and the bitterness of their invectives. An enlightened zeal for the energy and efficiency of government will be stigmatized as the offspring of a temper fond of despotic power and hostile to the principles of liberty. An over-scrupulous jealousy of danger to the rights of the people, which is more commonly the fault of the head than of the heart, will be represented as mere pretense and artifice, the stale bait for popularity at the expense of the public good. It will be forgotten, on the one hand, that jealousy is the usual concomitant of love, and that the noble enthusiasm of liberty is apt to be infected with a spirit of narrow and illiberal distrust. On the other hand, it will be equally forgotten that the vigor of government is essential to the security of liberty; that, in the contemplation of a sound and well-informed judgment, their interest can never be separated; and that a dangerous ambition more often lurks behind the specious mask of zeal for the rights of the people than under the forbidden appearance of zeal for the firmness and efficiency of government. History will teach us that the former has been found a much more certain road to the introduction of despotism than the latter, and that of those men who have overturned the liberties of republics, the greatest number have begun their career by paying an obsequious court to the people; commencing demagogues, and ending tyrants. . . .

It may perhaps be thought superfluous to offer arguments to prove the utility of the UNION, a point, no doubt, deeply engraved on the hearts of the great body of the people in every State, and one, which it may be imagined, has no adversaries. But the fact is, that we already hear it whispered in the private circles of those who oppose the new Constitution, that the thirteen States are of too great extent for any general system, and that we must of necessity resort to separate confederacies of distinct portions of the whole. This doctrine will, in all probability, be gradually propagated, till it has votaries enough to countenance an open avowal of it. For nothing can be more evident, to those who are able to take an enlarged view of the subject, than the alternative of an adoption of the new Constitution or a dismemberment of the Union. It will therefore be of use to begin by examining the advantages of that Union, the certain evils, and the probable dangers, to which every State will be exposed from its dissolution. This shall accordingly constitute the subject of my next address.

Explore the full document

Modal title.

Modal body text goes here.

Share with Students

Federalist Papers: About

Watch Videos

Learn More Online

Federalist Papers (Encyclopedia Britannica)

Federalist Papers (Constitutional Rights Foundation)

The Federalist Papers (History Channel)

Federalist Papers (Constitution Facts)

Federalist Papers Summarized (Tea Party)

Most Cited Federalist Papers (University of Minnesota Law School)

Federalist Papers Famous Quotes (A to Z Quotes)

About the Authors of the Federalist Papers (Library of Congress)

The Federalist Papers (Yale Law School - Avalon Project)

Federalist Papers Authored by Alexander Hamilton (Founding Fathers)

Federalist Papers Authored by John Jay (Founding Fathers)

Federalist Papers Authored by James Madison (Founding Fathers)

Unauthorized Propositions: The Federalist Papers and Constituent Power ( JSTOR )

Why are the Federalist Papers Important?

The Federalist, commonly referred to as the Federalist Papers, is a series of 85 essays written by Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, and James Madison between October 1787 and May 1788. The essays were published anonymously, under the pen name "Publius," in various New York state newspapers of the time.

The Federalist Papers were written and published to urge New Yorkers to ratify the proposed United States Constitution, which was drafted in Philadelphia in the summer of 1787. In lobbying for adoption of the Constitution over the existing Articles of Confederation, the essays explain particular provisions of the Constitution in detail. For this reason, and because Hamilton and Madison were each members of the Constitutional Convention, the Federalist Papers are often used today to help interpret the intentions of those drafting the Constitution.

The Federalist Papers were published primarily in two New York state newspapers: The New York Packet and The Independent Journal. They were reprinted in other newspapers in New York state and in several cities in other states. A bound edition, with revisions and corrections by Hamilton, was published in 1788 by printers J. and A. McLean. An edition published by printer Jacob Gideon in 1818, with revisions and corrections by Madison, was the first to identify each essay by its author's name. Because of its publishing history, the assignment of authorship, numbering, and exact wording may vary with different editions of The Federalist. Continue reading from Library of Congress

Federalist Paper Number One by Alexander Hamilton (1787)

After an unequivocal experience of the inefficiency of the subsisting federal government, you are called upon to deliberate on a new Constitution for the United States of America. The subject speaks its own importance; comprehending in its consequences nothing less than the existence of the UNION, the safety and welfare of the parts of which it is composed, the fate of an empire in many respects the most interesting in the world. It has been frequently remarked that it seems to have been reserved to the people of this country, by their conduct and example, to decide the important question, whether societies of men are really capable or not of establishing good government from reflection and choice, or whether they are forever destined to depend for their political constitutions on accident and force. If there be any truth in the remark, the crisis at which we are arrived may with propriety be regarded as the era in which that decision is to be made; and a wrong election of the part we shall act may, in this view, deserve to be considered as the general misfortune of mankind.

This idea will add the inducements of philanthropy to those of patriotism, to heighten the solicitude which all considerate and good men must feel for the event. Happy will it be if our choice should be directed by a judicious estimate of our true interests, unperplexed and unbiased by considerations not connected with the public good. But this is a thing more ardently to be wished than seriously to be expected. The plan offered to our deliberations affects too many particular interests, innovates upon too many local institutions, not to involve in its discussion a variety of objects foreign to its merits, and of views, passions and prejudices little favorable to the discovery of truth. Continue reading from Library of Congress

The Anti-Federalist Papers

Unlike the Federalist, the 85 articles written in opposition to the ratification of the 1787 United States Constitution were not a part of an organized program. Rather, the essays–– written under many pseudonyms and often published first in states other than New York — represented diverse elements of the opposition and focused on a variety of objections to the new Constitution. In New York, a letter written by “Cato” appeared in the New-York Journal within days of submission of the new constitution to the states, led to the Federalists publishing the “Publius” letters. “Cato”, thought to have been New York Governor George Clinton, wrote a further six letters. The sixteen “Brutus” letters, addressed to the Citizens of the State of New York and published in the New-York Journal and the Weekly Register, closely paralleled the “Publius” newspaper articles. Continue reading from Historical Society of the New York Courts

Check Out a Book from Our Collection...

- Last Updated: Oct 23, 2024 2:29 PM

- URL: https://westportlibrary.libguides.com/FederalistPapers2

The Magic of Writing

- STORIES FOR KIDS

This is a podcast for young writers to improve their writing skills and encourage creativity. Made by Maya Dimyati, age 8

Bonus Episode

This is a special bonus Episode for people who don't know which books they'll want to read. Maya will recommend some books she likes and that she thinks you will like.

Character Development

This episode is about develping your character to be more interesting

This episode shows that there are many different genres of writing, and it also shows how to use them and all about each one.

The Building Blocks of Stories

This episode is about the building blocks of stories and what to think about before you write one.

The Magic of Writing (Trailer)

Information.

- Creator Lisa Johnston

- Years Active 2K

- Rating Clean

- Copyright © Lisa Johnston

- Show Website The Magic of Writing

To listen to explicit episodes, sign in.

Stay up to date with this show

Sign in or sign up to follow shows, save episodes and get the latest updates.

Africa, Middle East, and India

- Brunei Darussalam

- Burkina Faso

- Côte d’Ivoire

- Congo, The Democratic Republic Of The

- Guinea-Bissau

- Niger (English)

- Congo, Republic of

- Saudi Arabia

- Sierra Leone

- South Africa

- Tanzania, United Republic Of

- Turkmenistan

- United Arab Emirates

Asia Pacific

- Indonesia (English)