Cirrhosis Case Study (45 min)

Watch More! Unlock the full videos with a FREE trial

Included In This Lesson

Study tools.

Access More! View the full outline and transcript with a FREE trial

Mr. Garcia is a 43-year-old male who presented to the ED complaining of nausea and vomiting x 3 days. The nurse notes a large, distended abdomen and yellowing of the patient’s skin and eyes. The patient reports a history of alcoholic cirrhosis.

What initial nursing assessments should be performed?

- Full abdominal assessment, including assessing for ascites

- Heart and lung sounds

- Skin assessment – color, turgor, etc.

- Full set of vital signs

- Neurological assessment

What diagnostic testing do you anticipate for Mr. Garcia?

- LFT’s, CBC, BMP

Mr. Garcia’s vitals are stable, BP 100/58, bowel sounds are active but distant, and the nurse notes a positive fluid wave test on his abdomen. The patient denies itching but is constantly scratching at his chest. He is oriented to person only and his brother at the bedside reports he hasn’t been himself today. He keeps trying to get out of bed

Which finding is most concerning and needs to be reported to the provider? Why?

- Confusion, disorientation – this could indicate hepatic encephalopathy, which could lead to seizures and death if left untreated

What further diagnostic and lab tests should be ordered to determine Mr. Garcia’s priority problems?

- Abdominal X-ray and/or Abdominal ultrasound to visualize liver and whether the distended abdomen is related to ascites or other sources

- Ammonia level to determine if hepatic encephalopathy is the source of Mr. Garcia’s altered mental status.

The provider places orders for the following:

Keep SpO 2 > 92%

Keep HOB > 30 degrees

Insert 2 large bore PIV’s

500 mL NS IV bolus STAT

100 mL/hr NS IV continuous infusion

Hydrocodone/Acetaminophen 5-500 mg 1-2 tabs q4h PRN moderate to severe pain

Diphenhydramine 25 mg PO q8h PRN itching

Ondansetron 4 mg IV q6h PRN nausea

Lactulose 20 mg PO q6h

Mr. Garcia’s LFT’s and Ammonia level are elevated. He is extremely confused and agitated and appears somewhat short of breath. The patient’s current vital signs are as follows:

HR 82 RR 22

BP 94/56 SpO 2 93%

Temp 98.9°F

Which order should be implemented first? Why?

- Insert two large-bore IV’s. The patient requires IV fluids and has other IV meds ordered and will likely need labs drawn. This needs to be a priority.

- You could also say elevate the HOB to 30 degrees or higher, if there was indication that he was lying flat

- His SpO2 is >92%, so no intervention is required there.

- Lactulose should be the next priority intervention – to get the ammonia levels down – but it may take a bit for pharmacy to profile it, send it to the unit, etc.

Which order should be questioned? Why?

- Hydrocodone/Acetaminophen – Acetaminophen can be toxic for patients with liver disease. The way this order is written, this patient could receive anywhere from 3 g – 6 g of Acetaminophen in a 24-hour period. The max for a healthy person is 4 g, but for liver patients, it is 2 g max.

- Either the dose and frequency should be lowered significantly, or the medication should be changed altogether

The order is changed to Fentanyl 25 mcg IV q4h PRN moderate to severe pain. The provider notes somewhat shallow breathing and severe ascites and requests for you to set up for paracentesis. At this time, you express your concern that the patient is extremely confused and agitated and trying to get out of bed. You do not feel that he will be still enough for the procedure. The provider agrees and plans to postpone the paracentesis for now, but orders for you to report any signs of respiratory depression or hypoxia.

Why is Mr. Garcia so confused and agitated?

- His ammonia levels are elevated due to his liver failure – this causes hepatic encephalopathy – damage to the brain cells

- This causes altered mental status, agitation, confusion, and can eventually lead to seizures and death if left untreated

What is the rationale for performing a paracentesis for Mr. Garcia?

- The excess fluid in Mr. Garcia’s belly is compressing his thoracic cavity, causing him to feel short of breath and to only take shallow breaths. Draining this fluid will not only relieve some discomfort, but it can also help improve Mr. Garcia’s breathing

After 6 doses of lactulose, Mr. Garcia is much more calm and cooperative. He is oriented times 2-3 most times. The provider performs the paracentesis and is able to remove 1.5 L of fluid. The patient’s shortness of breath is relieved, and his breathing is less shallow. Ultrasound of the liver showed severe scarring on the liver. Mr. Garcia’s condition continues to improve, and the plan is to discharge him home tomorrow.

What discharge teaching should be included for Mr. Garcia, including nutrition?

- Mr. Garcia should not be eating a high protein diet as this can contribute to the increased ammonia levels and development of hepatic encephalopathy.

- Mr. Garcia should avoid drinking alcohol at all times

- Medication instructions for any new or changed medications

- Especially the importance of taking Lactulose regularly as ordered

- Signs to report to the provider of exacerbation or encephalopathy

View the FULL Outline

When you start a FREE trial you gain access to the full outline as well as:

- SIMCLEX (NCLEX Simulator)

- 6,500+ Practice NCLEX Questions

- 2,000+ HD Videos

- 300+ Nursing Cheatsheets

“Would suggest to all nursing students . . . Guaranteed to ease the stress!”

Nursing Case Studies

This nursing case study course is designed to help nursing students build critical thinking. Each case study was written by experienced nurses with first hand knowledge of the “real-world” disease process. To help you increase your nursing clinical judgement (critical thinking), each unfolding nursing case study includes answers laid out by Blooms Taxonomy to help you see that you are progressing to clinical analysis.We encourage you to read the case study and really through the “critical thinking checks” as this is where the real learning occurs. If you get tripped up by a specific question, no worries, just dig into an associated lesson on the topic and reinforce your understanding. In the end, that is what nursing case studies are all about – growing in your clinical judgement.

Nursing Case Studies Introduction

Cardiac nursing case studies.

- 6 Questions

- 7 Questions

- 5 Questions

- 4 Questions

GI/GU Nursing Case Studies

- 2 Questions

- 8 Questions

Obstetrics Nursing Case Studies

Respiratory nursing case studies.

- 10 Questions

Pediatrics Nursing Case Studies

- 3 Questions

- 12 Questions

Neuro Nursing Case Studies

Mental health nursing case studies.

- 9 Questions

Metabolic/Endocrine Nursing Case Studies

Other nursing case studies.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Published: 28 March 2023

Global epidemiology of cirrhosis — aetiology, trends and predictions

- Daniel Q. Huang ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5165-5061 1 , 2 , 3 ,

- Norah A. Terrault 4 ,

- Frank Tacke ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6206-0226 5 ,

- Lise Lotte Gluud 6 , 7 ,

- Marco Arrese 8 , 9 ,

- Elisabetta Bugianesi 10 &

- Rohit Loomba ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4845-9991 1 , 11

Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology volume 20 , pages 388–398 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

111 Citations

116 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Epidemiology

- Liver cirrhosis

Cirrhosis is an important cause of morbidity and mortality in people with chronic liver disease worldwide. In 2019, cirrhosis was associated with 2.4% of global deaths. Owing to the rising prevalence of obesity and increased alcohol consumption on the one hand, and improvements in the management of hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus infections on the other, the epidemiology and burden of cirrhosis are changing. In this Review, we highlight global trends in the epidemiology of cirrhosis, discuss the contributions of various aetiologies of liver disease, examine projections for the burden of cirrhosis, and suggest future directions to tackle this condition. Although viral hepatitis remains the leading cause of cirrhosis worldwide, the prevalence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and alcohol-associated cirrhosis are rising in several regions of the world. The global number of deaths from cirrhosis increased between 2012 and 2017, but age-standardized death rates (ASDRs) declined. However, the ASDR for NAFLD-associated cirrhosis increased over this period, whereas ASDRs for other aetiologies of cirrhosis declined. The number of deaths from cirrhosis is projected to increase in the next decade. For these reasons, greater efforts are required to facilitate primary prevention, early detection and treatment of liver disease, and to improve access to care.

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection remains the leading cause of global deaths related to cirrhosis, followed by alcohol-associated liver disease.

The global burden of cirrhosis associated with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) has increased substantially in the past decade.

In the Americas, the dominant cause of cirrhosis is shifting from viral hepatitis to NAFLD and alcohol-associated liver disease.

The COVID-19 pandemic has set back progress in the elimination of HCV and hepatitis B virus, and most countries are not on track to meet the WHO viral hepatitis elimination targets.

The focus of care should be shifted upstream towards primary prevention and early detection of liver disease to reduce the global burden of cirrhosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

The incidence trends of liver cirrhosis caused by nonalcoholic steatohepatitis via the GBD study 2017

Global epidemiology of alcohol-associated cirrhosis and HCC: trends, projections and risk factors

Global epidemiology of NAFLD-related HCC: trends, predictions, risk factors and prevention

Introduction.

Cirrhosis is an important cause of morbidity and mortality among patients with chronic liver disease 1 . Cirrhosis can lead to hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and hepatic decompensation, including ascites, hepatic encephalopathy and variceal bleeding 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , and is a leading cause of death worldwide — it was associated with 2.4% of global deaths in 2019 (ref. 8 ). The major aetiologies of cirrhosis are hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, alcohol-associated liver disease and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) 9 , 10 . However, the past decade has seen major changes in the aetiology and burden of liver disease 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 .

Increasing HBV vaccination coverage and improved availability of effective antivirals against HBV have contributed to a reduction in the global age-standardized death rates (ASDRs) for HBV-associated cirrhosis 12 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 . Similarly, since 2015, safe and effective directly acting antivirals (DAAs) have revolutionized treatment of HCV infection, although the full impact of DAAs on the global burden of HCV-associated cirrhosis is unclear 12 , 21 , 22 , 23 . Despite the rising consumption of alcohol 24 , 25 , ASDRs for alcohol-associated cirrhosis have decreased, although under-reporting and under-diagnosis are a concern 26 . By contrast, the obesity and diabetes epidemic has led to a rapid rise in the prevalence of NAFLD, and ASDRs for NAFLD-associated cirrhosis have increased 26 .

Estimates of the global burden of cirrhosis and of the contributions made by various causes of liver disease are important for practitioners, researchers and health-care policymakers to inform clinical practice, provide directions for research and guide the use of resources, respectively. In this Review, we highlight global trends in the epidemiology of cirrhosis, discuss the contributions of various aetiologies of liver disease, examine projections for the burden of cirrhosis, and suggest future directions for reducing the burden of cirrhosis.

Prevalence of cirrhosis

The Global Burden of Disease (GBD) Study provides a comprehensive overview of the estimated global burden of cirrhosis and chronic liver diseases (which are collectively referred to as cirrhosis in the GBD Study) 27 , 28 . In the GBD Study 2017, the estimated number of people with compensated cirrhosis was 112 million worldwide, corresponding to an age-standardized global prevalence of compensated cirrhosis of 1,395 cases per 100,000 population 12 .

The data used in the GBD Study depended on the quality of each country’s registry 27 , and where data were not available, modelling was used to extrapolate from previous trends. Such extrapolation could have introduced bias, which would have reduced the accuracy of these prevalence estimates. In regions with lower standards of health care, cirrhosis is likely to be under-reported owing to a lack of disease awareness and access to care. In light of these limitations, interpretation of data from the GBD Study requires caution, but the study remains an important source of information about the burden of cirrhosis.

Several country-specific, population-based studies conducted in Europe have examined the prevalence of cirrhosis on the basis of non-invasive tests. Estimates of prevalence in these studies have ranged from 0.3% to 0.8% 29 . However, such data on the global prevalence of cirrhosis are limited.

Aetiologies of liver disease

The prevalence of HBV and HCV infection among individuals with cirrhosis was estimated in a large systematic review and meta-analysis of 520 studies (including 1,376,503 individuals from 86 countries or territories) published between 1993 and 2021 (ref. 30 ). Although the primary aim of this study was to evaluate the prevalence of HBV and HCV infection, data on heavy alcohol consumption and NAFLD were also reported where available. The analysis included only studies of unselected patients with cirrhosis, who were assumed to be representative of the population at each centre.

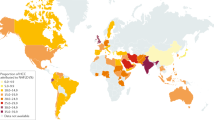

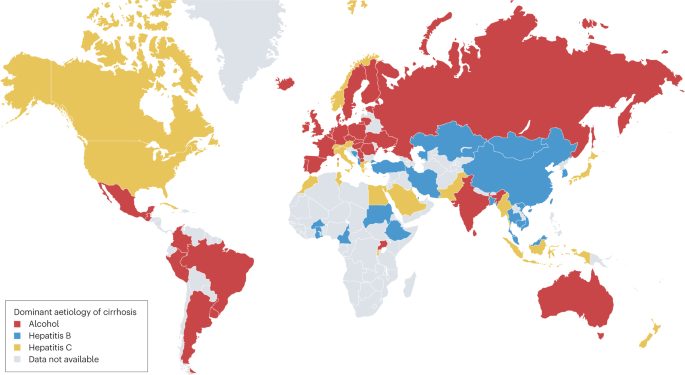

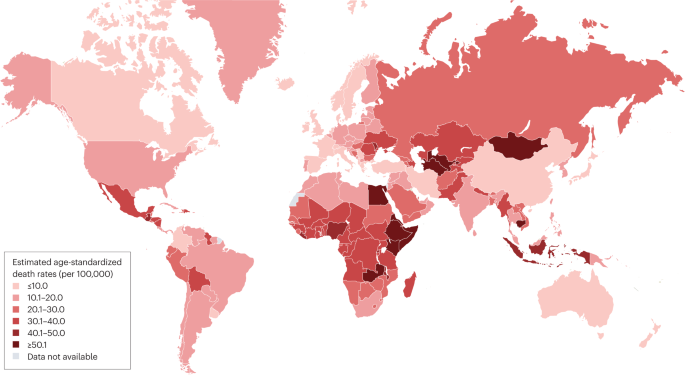

Globally, among individuals with cirrhosis, 42% had HBV infection and 21% had HCV infection. By WHO region, the prevalence of HBV infection among patients with cirrhosis was highest in the Western Pacific region (59%) and lowest in the Americas (5%), whereas the highest prevalence of HCV infection among patients with cirrhosis was in the Eastern Mediterranean region (70%) and the lowest was in Africa and the Western Pacific (both 13%). The proportion of patients with cirrhosis and heavy alcohol use was high in Europe (16–78%) and the Americas (17–52%) and was generally lower in Asia (0–41%). Data on the prevalence of NAFLD among patients with cirrhosis in this study were more limited, but estimates ranged from 2% in South Korea and Brazil to 18% in Canada (when considering estimates based on at least three studies). The dominant reported cause of cirrhosis varied by country (Fig. 1 ).

Data were obtained from a systematic review of cirrhosis that included studies published during the period 1993–2021 (ref. 30 ).

Interpretation of the data from this large meta-analysis requires caution. The primary aim of the meta-analysis was to evaluate the prevalence of viral hepatitis, rather than heavy alcohol use or NAFLD, in cirrhosis, so studies relevant to alcohol use and NAFLD might have been omitted. In addition, many of the included studies did not account for multiple aetiologies of cirrhosis. We speculate that cirrhosis has more than one cause in a substantial proportion of patients, particularly considering the growing prevalence of obesity and increasing alcohol consumption.

In addition, the concept of metabolic-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) is likely to alter the apparent aetiology of cirrhosis. MAFLD is defined — on the basis of recently proposed criteria 31 , 32 — as hepatic steatosis with obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus or other factors associated with metabolic dysfunction without the need to exclude alternative causes of chronic liver disease, such as viral hepatitis or alcohol consumption 32 . Data on the global burden of MAFLD-associated cirrhosis are limited, but we speculate that the burden of MAFLD-associated cirrhosis will increase over time owing to an increasing proportion of individuals with more than one cause of liver disease, such as concomitant alcohol consumption and NAFLD, or concomitant NAFLD and viral hepatitis. Finally, as the studies included in this meta-analysis spanned nearly 30 years, the data might not reflect the trends in the past decade.

Trends in the aetiology of cirrhosis

Studies from across the world provide insights into trends in the aetiology of cirrhosis (Supplementary Table 1 ); these trends are discussed by WHO region in the sections that follow. Many of the larger studies conducted in North America, Europe and the Western Pacific were based on data from administrative disease registries and relied on International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes (Box 1 ) to identify cases of cirrhosis; this approach is susceptible to bias related to incomplete records or incorrect coding. By contrast, studies in which clinical criteria and chart review were used to identify cases of cirrhosis are less susceptible to bias, but many such studies included modest sample sizes and, consequently, might not fully reflect trends in aetiology.

Similarly, the definitions of NAFLD-associated cirrhosis varied across studies, so interpretation of data based on these definitions requires caution. Criteria for NAFLD as a cause of cirrhosis have been proposed to enable consistent enrolment into clinical trials 33 . These criteria enable categorization of the likelihood that NAFLD is the cause of cirrhosis (definite, probable or possible) on the basis of histological evidence and metabolic risk factors 33 . However, these criteria have not been uniformly adopted and might require further validation.

Box 1 International Classification of Diseases codes for cirrhosis

Multiple studies have been conducted in North America, Europe and Australia to examined the use of International Classification of Diseases 9 (ICD-9) and ICD-10 codes to identify cirrhosis 36 , 113 , 114 , 115 , 116 , 117 , 118 , 119 , 120 , 121 . These studies showed that ICD codes used to identify cirrhosis generally have a relatively high positive predictive value but, when used in isolation, they have only modest sensitivity for identifying cirrhosis 36 , 113 , 115 .

Algorithms that use a combination of ICD codes, or a combination of ICD codes and laboratory results, could improve diagnostic accuracy 36 , 113 , 115 , 122 . One systematic review has identified nine ICD-10 codes that have been used to identify cirrhosis most frequently in the literature 118 . When validated in Europe and North America, this set of nine ICD-10 codes had greater sensitivity than the code set most frequently used in the literature 121 , and maintained a high positive predictive value (83–89%). This consensus code set could, therefore, be a useful tool for identification of cirrhosis in large databases and health records, and should be further validated in regions outside North America and Europe 118 .

The Americas

Multiple studies conducted in the Americas indicate a shift in the dominant cause of cirrhosis over the past 10–20 years. In a population-based study conducted in Indiana, USA, analysis of the incident cases of cirrhosis from 2004 to 2014 ( n = 9,261) 16 identified increases in the proportion of patients with alcohol-associated cirrhosis (0.8% per year) and NAFLD-associated cirrhosis (0.6% per year), whereas the proportion with viral hepatitis decreased by 1.4% per year 16 . In a prospective study in 1,717 people with cirrhosis at five hospitals in Texas, USA, between 2016 and 2019, the major causes of cirrhosis were cured HCV infection (33%), alcohol consumption (31%) and NAFLD (23%), highlighting the shift away from active viral hepatitis as the dominant cause of cirrhosis 34 . Similarly, in an analysis of population-based administrative health-care data from 159,549 people with cirrhosis in Ontario, Canada, the most common causes of incident cirrhosis between 2000 and 2017 were NAFLD (53%) and alcohol consumption (24%) 35 . However, this study differed from other studies conducted in Canada, in which the leading cause of cirrhosis was HCV infection — some degree of misclassification bias might have contributed to the high estimated proportion of cirrhosis caused by NAFLD 36 , 37 .

Changes in the aetiology of cirrhosis over time in Mexico were assessed in a study including 4,584 people who were diagnosed with incident cirrhosis in six tertiary hospitals between 2000 and 2019 (ref. 38 ). In this study, diagnostic criteria for MAFLD 31 , 32 , rather than NAFLD, were used. MAFLD was identified as the third most common cause of incident cirrhosis in 2000 (14%) but had become the leading cause of incident cirrhosis (36%) in 2019. By contrast, HCV infection was the leading cause of cirrhosis in 2000 (45%) but had declined by 2019 (11%). The proportion of cirrhosis cases due to alcohol consumption increased from 28% to 33% during the study period. However, the way in which patients who fulfilled the criteria for MAFLD and had concomitant viral hepatitis or high alcohol consumption were classified was not clear 38 . Finally, a study of the United Network for Organ Sharing database from 2014 to 2019 determined that NAFLD and alcohol consumption have become the most common causes of liver disease among people without HCC waiting for a liver transplant 39 .

Taken together, these data suggest that the aetiology of cirrhosis in the Americas is shifting from active HBV and HCV infection towards resolved or treated viral hepatitis, alcohol consumption and NAFLD. These data are in line with increases in obesity and alcohol consumption in the Americas 40 , 41 , 42 .

As in the Americas, studies in Europe indicate a change in the dominant aetiology of cirrhosis. Analysis of data from all hospital admissions in Germany from 2005 to 2018 revealed that the prevalence of NAFLD-associated cirrhosis increased fourfold during the study period 43 . Nevertheless, alcohol consumption remained the dominant cause of cirrhosis in Germany in 2018, accounting for 52% of cirrhosis cases; NAFLD and NASH accounted for only 3% and 1%, respectively. In Sweden, in a cohort study in patients with cirrhosis who visited a tertiary hospital, the proportion of patients with cirrhosis due to viral hepatitis declined from 43% in the first 5 years (2004–2008) of the study to 31% in the final 4 years (2014–2017), whereas the proportion due to NAFLD increased from 6% to 15% in the same period 44 . Similarly, in Italy, in a multicentre study in patients with cirrhosis ( n = 832) at 16 hospitals 45 , the proportions of people with cirrhosis due to alcohol consumption and HCV infection decreased, whereas the proportion of people with cirrhosis due to NAFLD increased when compared with a historical cohort (2001) 46 .

Collectively, these data indicate that the prevalence of NAFLD-associated cirrhosis is increasing in Europe, whereas the prevalence of alcohol-associated cirrhosis seems to be decreasing, possibly in response to public health measures such as the enforcement of a minimum price for alcohol and increased alcohol taxation 41 , 47 , 48 . The data also suggest that the prevalence of HCV-associated and HBV-associated cirrhosis is declining in Europe.

Africa, the Eastern Mediterranean and Southeast Asia

Limited data are available on trends in the aetiology of cirrhosis in Africa, the Eastern Mediterranean and Southeast Asia, as many studies conducted in these regions have included modest sample sizes 30 . More data are required from these regions to accurately determine trends in the aetiology of cirrhosis and to identify and address the gaps in linkage to care.

In Africa, research on liver diseases is a major unmet need. Estimates from the GBD Study determined that most cases of cirrhosis in Africa were related to HBV infection, alcohol consumption and HCV infection, but no other up-to-date population-based data exist for the aetiologies of cirrhosis 12 , 49 , 50 . Data from larger studies of HCC in Africa can provide some indication of the relative contributions that each aetiology of liver disease makes to the prevalence of cirrhosis, although some people with HCC do not have cirrhosis, so caution is required in interpreting the data. In one study, analysis of 1,251 people with HCC (all of whom had cirrhosis) from Egypt determined that the dominant aetiology was HCV infection (84%), followed by other or unknown causes (12%), HBV–HCV co-infection (2%) and HBV infection (1%) 51 . In the same study, analysis of 1,315 people with HCC (66% of whom had cirrhosis) from other African countries (Nigeria, Ghana, the Ivory Coast, Cameroon, Sudan, Ethiopia, Tanzania and Uganda) determined that the most common aetiology was HBV infection (55%), followed by other or unknown causes (22%), alcohol consumption (13%) and HCV infection (6%) 51 .

In the Eastern Mediterranean region, single-centre studies suggest that viral hepatitis remains the dominant cause of cirrhosis. For example, in one study of 953 Jewish and 95 Arab Bedouin individuals with cirrhosis at a tertiary hospital in Israel determined that the most common cause of cirrhosis was HCV infection (39%) among Jewish individuals and NAFLD (21%) among Bedouin individuals 52 . In Qatar, study of 109 individuals with cirrhosis who were admitted to an intensive care unit showed that the most common aetiology of cirrhosis was HCV infection (34%), followed by alcohol consumption (26%), cryptogenic liver disease (24%) and HBV infection (21%) 53 . However, population-based data from this region are lacking and are needed to get a more accurate understanding of aetiology.

Data from the Southeast Asia region are similarly limited. In one study conducted in India, the most common aetiology among 4,413 patients with cirrhosis from 11 hospitals was alcohol consumption (34%), followed by other causes (29%), HBV infection (18%), HCV infection (17%) and NAFLD (2%) 54 . However, among 192 people with cirrhosis who underwent endoscopic band ligation in a hospital in Pakistan, cirrhosis was attributed to HCV infection in 63% and to HBV infection in 19% 55 .

The Western Pacific

Studies in the Western Pacific region have shown that NAFLD-associated and alcohol-associated cirrhosis are increasing in this region, but viral hepatitis remains the dominant cause of cirrhosis 30 . These trends were demonstrated in a large study in 48,621 individuals with cirrhosis identified on the basis of clinical criteria at 79 hospitals in Japan 56 . Comparison of aetiology in 2007 with that in 2014–2016 demonstrated an increase in NAFLD-associated cirrhosis (2% to 9%) and alcohol-associated cirrhosis (14% to 25%). The proportion of cirrhosis cases due to HCV and HBV infection declined (from 59% to 40% and from 14% to 9%, respectively), although these remained the largest contributors. In another study in 15,716 patients with cirrhosis at five university hospitals in South Korea between 2000 and 2014, the proportion of cirrhosis cases due to NAFLD, alcohol consumption and HCV infection increased over the study period 57 . However, the study periods of both of these studies were before the widespread availability of DAA therapy for HCV infection, which is likely to reduce the proportion of cirrhosis cases that are due to HCV infection over time.

Also in the Western Pacific region, analysis of data from 1,582 individuals with a new diagnosis of cirrhosis at a hospital in China determined that the proportion of NAFLD-associated cirrhosis cases was higher (3%) in the last 2 years of the study (2012–2013) than the average (2%) over the entire study period (2003–2013) 58 . In Taiwan, analysis of data from 18,423 individuals with HCC who were diagnosed between 1981 and 2001 showed that the percentage of HBV-associated HCC decreased from 82% to 66% among men and from 67% to 41% among women over the study period owing to an increase in HCV-associated HCC 59 . Despite the continued dominance of viral hepatitis as a cause of cirrhosis in the Western Pacific region, tracking changes in the aetiology of cirrhosis over time remains important, as the rates of obesity and alcohol consumption continue to rise in parallel with increasing economic wealth 24 , 41 , 60 , 61 , 62 , 63 .

Decompensated cirrhosis

Hepatic decompensation is potentially preventable with antiviral therapy (in HBV-associated and HCV-associated cirrhosis) and lifestyle changes (in alcohol-associated and NAFLD-associated cirrhosis), but epidemiological data suggest that decompensated cirrhosis is increasing in prevalence. In prior studies in patients with compensated cirrhosis, transition from a compensated state to a decompensated state (including ascites, hepatic encephalopathy and variceal bleeding) occurred at a rate of 5–12% per year 64 , 65 , 66 . Data from the GBD Study 2017 indicate that the global number of prevalent cases of decompensated cirrhosis increased from 5.2 million in 1990 to 10.6 million in 2017, corresponding to an increase in the estimated age-standardized prevalence of decompensated cirrhosis from 110.6 per 100,000 population in 1990 to 132.5 per 100,000 population in 2017 (ref. 12 ). In 2017, the proportion of decompensated cirrhosis associated with HBV and HCV infection, alcohol consumption, NAFLD and other causes was 28%, 25%, 23%, 9% and 16%, respectively 12 .

Acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF) is characterized by acute decompensation of chronic liver disease that is associated with organ failure and carries a high risk of mortality 67 , 68 . Several definitions exist for ACLF, including criteria from the Asia Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver 69 , the European Association for the Study of the Liver–Chronic Liver Failure (EASL–CLIF) 70 , and the North American Consortium for the Study of End-Stage Liver 71 . ACLF has been reviewed in detail elsewhere 67 , 72 . A meta-analysis of 30 studies determined that the global prevalence of ACLF (defined by the EASL–CLIF criteria) among patients admitted with decompensated cirrhosis was 35% 73 . Alcohol consumption was the underlying cause of chronic liver disease in 45% of people with ACLF globally; regional pooled estimates ranged from 24% in North America to 55% in Europe 73 . The global 90-day mortality associated with ACLF was 58% and ranged from 41% in North America to 68% in Southeast Asia 73 .

In combination, these data highlight the need for increased efforts to identify liver disease at an earlier stage. Earlier identification would enable the use of preventive measures, thereby reducing the burden of decompensation 74 .

Deaths associated with cirrhosis

The GBD Study 2019 provides a comprehensive global overview of the estimated mortality associated with cirrhosis (and chronic liver diseases) 27 . Although deaths attributed to liver cancer were excluded from this analysis, the proportions of liver cancer due to the various aetiologies of liver disease were used as co-variates in determining the proportion of cirrhosis deaths due to the various aetiologies of liver disease. The analysis provided global and regional estimates for the number of deaths and ASDRs associated with cirrhosis in 2019 (Table 1 ).

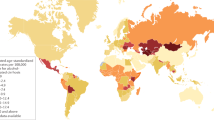

The estimated number of deaths associated with cirrhosis worldwide in 2019 was 1,472,000 (ref. 27 ). This number had increased by 10% from 2010 (ref. 27 ). The absolute number of deaths associated with cirrhosis was lowest in the Eastern Mediterranean region (146,000) and highest in Southeast Asia (443,000). The estimated global ASDR for cirrhosis in 2019 was 18 deaths per 100,000 population 27 (Table 1 ). By region, the lowest estimated ASDR was in the Western Pacific (9.6 deaths per 100,000 population) and the highest was in the Eastern Mediterranean region (36.2 deaths per 100,000 population). The disconnect between the number of cirrhosis-related deaths and the ASDR in the Eastern Mediterranean region results from the relatively small and young population in that region 75 . The estimated ASDR in different countries (Fig. 2 ) ranged from 3.3 deaths per 100,000 population in Singapore to 126.7 deaths per 100,000 population in Egypt.

Data for the age-standardized death rate in 2019 were estimated in the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019 and these data were obtained from the GBD Results Tool 27 . Where data for countries or regions were unavailable, the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019 results depended on modelling and past trends, potentially resulting in discrepancies in the accuracy of the data.

The number of deaths associated with cirrhosis with different aetiologies (Table 1 ) ranged from 134,241 deaths for NAFLD-associated cirrhosis to 395,022 for HCV-associated cirrhosis. The corresponding estimated ASDRs ranged from 1.7 deaths per 100,000 population for NAFLD-associated cirrhosis to 4.8 deaths per 100,000 population for HCV-associated cirrhosis 27 . However, a substantial proportion of cases of cirrhosis that were categorized as having ‘other causes’ in the GBD Study might have been due to NAFLD or occult HBV infection, which would mean that the figures for NAFLD-associated and HBV-associated cirrhosis are underestimates.

Data from the GBD Study 2017 has provided insight into temporal trends in deaths associated with cirrhosis. Between 2012 and 2017, the number of deaths associated with cirrhosis increased by 9%, although the global ASDR for cirrhosis declined from 17.1 to 16.5 deaths per 100,000 population (ref. 26 ). The disconnect between the number of deaths and ASDR is due to population growth and ageing. The ASDRs for HBV-associated cirrhosis, HCV-associated cirrhosis and alcohol-associated cirrhosis also decreased by 1.4%, 0.5% and 0.4%, respectively, between 2012 and 2017. By contrast, the ASDR for NAFLD-associated cirrhosis increased by 0.3% over the same period 26 . However, cardiovascular diseases are the leading cause of death among patients with NAFLD, highlighting the need for a multidisciplinary approach to this condition 76 , 77 , 78 .

Predictions

Several modelling studies been done to project the burden of various aetiologies of cirrhosis over the next decade 22 , 35 , 79 , 80 , 81 , 82 . However, these studies should be interpreted with caution. The input data were largely derived from administrative databases, which are susceptible to bias, including under-reporting and misclassification bias. In addition, fibrosis can regress after antiviral treatment or lifestyle modification but few of these modelling studies accounted for the possibility of such regression 83 , 84 , 85 , 86 . Despite these limitations, the resulting data serve as an important reference to guide public health policymakers and researchers.

HCV-associated cirrhosis

Integration of a literature review, a Delphi process and Markov modelling to forecast the burden of incident decompensated HCV-associated cirrhosis in 2030 led to an estimated increase from 148,000 cases in 2020 to 174,000 in 2030 worldwide 22 . However, the rate of cases per 100,000 population was projected to remain relatively stable. The same modelling study also provided an estimate of the prevalence of viraemic HCV infection, which indicated that the global hepatitis elimination target for 2030 is unlikely to be attained should current trends persist 87 .

Caution must be exercised when interpreting the estimates from this study, as sufficient data for model generation were available for fewer than half of the countries. In addition, treatment rates were uncertain, especially for countries in which a substantial proportion of treatments were exported for overseas use. Nevertheless, the COVID-19 pandemic has set back the progress made in HCV elimination 88 , 89 (Box 2 ), and these data serve as a call to action for an increased emphasis on HCV elimination.

Box 2 Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on cirrhosis

Population-based analyses conducted in the USA determined that mortality due to cirrhosis increased markedly during the COVID-19 pandemic 123 . Evidence from multiple countries has demonstrated that alcohol consumption increased substantially during the pandemic 97 , 124 , 125 , 126 , 127 , 128 , and the observed increase in mortality was mainly related to alcohol-associated cirrhosis 123 .

Among patients with COVID-19 and chronic liver disease in the US National COVID Cohort Collaborative, the presence of cirrhosis was associated with an increased risk of mortality (adjusted HR 3.3) 129 .

In the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic, cirrhosis referrals, hospitalizations and clinic visits declined substantially, which might have contributed to lower quality of care, delayed presentation and loss of follow-up 95 , 96 , 130 , 131 .

A global study conducted at 44 international centres determined that consultations, testing and treatment rates for hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus infection decreased substantially between January 2019 and December 2020, and this decrease was related to the COVID-19 pandemic 89 .

Modelling of a 1-year delay to the hepatitis C elimination programmes of 110 countries owing to the COVID-19 pandemic indicated that such a delay would result in 72,300 excess liver-related deaths (likely to be related to HCV-associated cirrhosis in the majority of these cases) over the next 10 years relative to the situation with no delay 132 .

HBV-associated cirrhosis

Data on the projected global burden of HBV-associated cirrhosis are limited. Projections in one study suggest that the incidence of HBV infection will fall by 2030 but that HBV-related deaths will increase by 39% between 2015 and 2030 (ref. 81 ). Data from the GBD Study 2019 showed that only four countries had attained the WHO Global Health Sector Strategy on Viral Hepatitis 2020 interim impact target of a 10% reduction in deaths between 2015 and 2019 (ref. 90 ). Furthermore, despite the availability of vaccines and life-saving antiviral therapy, HBV infection remains severely under-diagnosed, so a minority of treatment-eligible patients receive antiviral treatment 91 , 92 , and the COVID-19 pandemic has hindered HBV elimination efforts globally 89 (Box 2 ). Together, these observations highlight that HBV is likely to remain a major threat to public health in the next decade, and increased political will and resources are required to eliminate HBV, which remains a major cause of cirrhosis and HCC worldwide.

Alcohol-associated cirrhosis

In a study in the USA, data from the National Vital Statistics System, the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, the National Death Index, the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions, and other published data were used to predict outcomes from alcohol-associated liver disease in the USA between 2019 and 2040 (ref. 82 ). The result was a predicted increase of 77% in the age-standardized incidence of decompensated alcohol-associated cirrhosis, from 9.9 cases per 100,000 patient-years in 2019 to 17.5 cases per 100,000 patient-years in 2040, should current trends be left unchecked 82 .

In a study conducted in Canada, cirrhosis incidence rates were calculated from the crude rates observed in Ontario between 2000 and 2017, and projections of incidence were calculated on the basis of the estimated population of Ontario from 2018 to 2040 (ref. 35 ). The incidence of cirrhosis (of all aetiologies) was projected to increase by 9% between 2018 and 2040, with a steady increase in the age-standardized incidence rate for alcohol-associated cirrhosis.

The projected burden of alcohol-associated cirrhosis in these studies might be underestimated owing to under-reporting. In addition, neither study accounted for comorbid diseases, such as concomitant HCV infection, which could increase the rate of fibrosis progression. Nevertheless, these data indicate that the burden of alcohol-associated cirrhosis in North America is likely to increase further unless alcohol-related policies are instituted or specific therapies become available for alcohol-associated liver disease. Data for the projected burden of alcohol-associated cirrhosis outside North America are limited.

One additional point to consider is that the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in an increase in alcohol consumption in many countries (Box 2 ). This increase in alcohol consumption could further increase the global burden of alcohol-associated cirrhosis in the coming years 93 , 94 , 95 , 96 , 97 , 98 .

NAFLD-associated cirrhosis

Several studies have generated predictions about the burden of NAFLD-associated cirrhosis by 2030. In one study, the prevalence of NAFLD in China, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Spain, the UK and the USA was predicted on the basis of published data, expert consensus and country-level prevalence of obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus 80 . Markov modelling was then used to project the burden of NAFLD-associated cirrhosis in 2030 (ref. 80 ). The smallest projected increase in the prevalence of compensated NAFLD-associated cirrhosis cases was 64% in Japan and the largest projected increase was 156% in France. The smallest projected increase in the prevalence of decompensated NAFLD-associated cirrhosis cases was 75% in Japan and the largest projected increase was 187% in France.

A similar methodology was used in another study to forecast the burden of NAFLD-associated cirrhosis in 2030 in Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea and Taiwan 79 . From 2019 to 2030, incident decompensated NAFLD-associated cirrhosis was projected to increase by 65% in Hong Kong, 85% in South Korea and 100% in Singapore and Taiwan. In both studies, definitions of NAFLD varied between the input sources, contributing to variation in the projected prevalence of NAFLD.

In the Canadian study of cirrhosis discussed above 36 , projections indicated that NAFLD-associated cirrhosis would account for 75% of incident cases of cirrhosis in Ontario by 2040. These data require cautious interpretation, as the proportion of historical cirrhosis cases due to NAFLD was much higher than estimates in other Canadian studies 36 , 37 . Taken together, however, these data highlight the growing burden of NAFLD-associated cirrhosis and the need for urgent measures to control the underlying metabolic risk factors at a global and regional level.

Future directions

Liver disease is often under-diagnosed, and many individuals present late with decompensated cirrhosis 99 , 100 . Disadvantaged and under-served communities are often disproportionately affected by liver disease but often lack timely access to appropriate care 91 , 101 , 102 . Despite advances in the diagnosis, treatment and management of cirrhosis, medical interventions often have limited benefit on long-term survival, necessitating the use of resource-heavy treatments such as liver transplantation 7 , 103 , 104 , 105 , 106 . Therefore, the focus of care should be shifted upstream, from the management of complications to prevention and early treatment 74 .

As an example, consumption of alcohol per capita (alcohol consumption within one calendar year in litres of pure alcohol in people aged ≥15 years) in Europe has declined over time (12.3 l in 2005 to 9.8 l in 2016), and this decline is related to policies that enforce a minimum price for alcohol and increased alcohol taxation 26 , 41 , 47 , 48 . The strong political will required to implement these policies has contributed to a reduction in mortality from alcohol-associated cirrhosis in Europe over the past decade 26 , 41 , 47 , 48 . By contrast, in the Americas, Western Pacific and Southeast Asia, ASDRs due to alcohol-associated cirrhosis increased during the same time period 26 . A consensus statement published in 2021 highlighted the fact that most countries in the world lack a national strategy for NAFLD, reflecting the low priority of this disease in national health agendas 107 . Greater efforts are required at national and regional levels to implement public health policies that target the metabolic risk factors for liver diseases, such as high-sugar foods, lack of physical activity and heavy alcohol consumption 108 .

A case-finding approach could help to detect patients with early cirrhosis or advanced fibrosis, and thereby facilitate treatment. In a population-based, prospective cohort study conducted in Germany, a structured screening programme (a combination of routine serum tests including aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase and platelet levels) of individuals participating in health check-ups was associated with 59% higher odds of detecting early cirrhosis compared with routine care, after excluding individuals with decompensated cirrhosis 109 . The American Gastroenterological Association has proposed a clinical care pathway to facilitate risk stratification and management of individuals with NAFLD in primary care, endocrinology and obesity medicine, which could strengthen linkage to tertiary care but requires prospective validation 110 .

Outreach efforts to improve screening, treatment and linkage to care for viral hepatitis are effective but are not widely adopted 22 , 111 . The Polaris Observatory estimated that only 1% of prevalent cases of HCV infection worldwide were treated in 2020, and <10% of treatment-eligible individuals with HBV infection received antiviral treatment 22 , 81 . These sobering figures highlight the uphill task faced by the global hepatology community, and underscore the need for stronger multidisciplinary collaboration between primary care physicians, preventive care specialists, nurse practitioners, infectious disease specialists, hepatologists, patient representatives and policymakers.

Conclusions

The aetiology of cirrhosis is changing, and the global burden of NAFLD-associated cirrhosis is steadily rising in parallel with the epidemic of obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Global alcohol consumption continues to rise, and national policies are required to reduce the burden of alcohol-associated cirrhosis. Despite the availability of effective antiviral therapies for HCV and HBV infection, most countries are not on track to meet the WHO viral hepatitis elimination targets. The burden of cirrhosis remains substantial owing to under-diagnosis and under-treatment of chronic liver disease, and the number of deaths and cases of decompensated cirrhosis are projected to rise in the next decade. More resources should be directed towards primary prevention, early detection of liver disease and linkage to care to reduce the global burden of cirrhosis.

Ginès, P. et al. Liver cirrhosis. Lancet 398 , 1359–1376 (2021).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Tapper, E. B., Ufere, N. N., Huang, D. Q. & Loomba, R. Review article: current and emerging therapies for the management of cirrhosis and its complications. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 55 , 1099–1115 (2022).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Tapper, E. B. & Parikh, N. D. Mortality due to cirrhosis and liver cancer in the United States, 1999-2016: observational study. BMJ 362 , k2817 (2018).

Huang, D. Q. et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma incidence in alcohol-associated cirrhosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2022.06.032 (2022).

Tan, D. J. H. et al. Clinical characteristics, surveillance, treatment allocation, and outcomes of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease-related hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 23 , 521–530 (2022).

Tan, D. J. H. et al. Global burden of liver cancer in males and females: changing etiological basis and the growing contribution of NASH. Hepatology https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.32758 (2022).

Ajmera, V. et al. Liver stiffness on magnetic resonance elastography and the MEFIB index and liver-related outcomes in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of individual participants. Gastroenterology 163 , 1079–1089.e5 (2022).

The Global Health Observatory. Global health estimates: Leading causes of death. WHO https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/mortality-and-global-health-estimates/ghe-leading-causes-of-death . (2023).

Moon, A. M., Singal, A. G. & Tapper, E. B. Contemporary epidemiology of chronic liver disease and cirrhosis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 18 , 2650–2666 (2020).

Loomba, R., Friedman, S. L. & Shulman, G. I. Mechanisms and disease consequences of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Cell 184 , 2537–2564 (2021).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Asrani, S. K., Devarbhavi, H., Eaton, J. & Kamath, P. S. Burden of liver diseases in the world. J. Hepatol. 70 , 151–171 (2019).

GBD 2017 Cirrhosis Collaborators.The global, regional, and national burden of cirrhosis by cause in 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 5 , 245–266 (2020).

Article Google Scholar

Huang, D. Q. et al. Changing global epidemiology of liver cancer from 2010 to 2019: NASH is the fastest growing cause of liver cancer. Cell Metab. 34 , 969–977.e2 (2022).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Huang, D. Q., El-Serag, H. B. & Loomba, R. Global epidemiology of NAFLD-related HCC: trends, predictions, risk factors and prevention. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 18 , 223–238 (2021).

Golabi, P. et al. Burden of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in Asia, the Middle East and North Africa: Data from Global Burden of Disease 2009-2019. J. Hepatol. 75 , 795–809 (2021).

Orman, E. S. et al. Trends in characteristics, mortality, and other outcomes of patients with newly diagnosed cirrhosis. JAMA Netw. Open. 2 , e196412 (2019).

Chen, V. L. et al. Anti-viral therapy is associated with improved survival but is underutilised in patients with hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma: real-world east and west experience. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 48 , 44–54 (2018).

Terrault, N. A. et al. Update on prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of chronic hepatitis B: AASLD 2018 hepatitis B guidance. Hepatology 67 , 1560–1599 (2018).

European Association for the Study of the Liver EASL 2017 Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of hepatitis B virus infection. J. Hepatol. 67 , 370–398 (2017).

Sarin, S. K. et al. Asian-Pacific clinical practice guidelines on the management of hepatitis B: a 2015 update. Hepatol. Int. 10 , 1–98 (2016).

Ghany, M. G. & Morgan, T. R. AASLD-IDSA Hepatitis C Guidance Panel Hepatitis C guidance 2019 update: American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases–Infectious Diseases Society of America recommendations for testing, managing, and treating hepatitis C virus infection. Hepatology 71 , 686–721 (2020).

Polaris Observatory HCV Collaborators.Global change in hepatitis C virus prevalence and cascade of care between 2015 and 2020: a modelling study. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 7 , 396–415 (2022).

European Association for the Study of the Liver EASL recommendations on treatment of hepatitis C: final update of the series. J. Hepatol. 73 , 1170–1218 (2020).

Manthey, J. et al. Global alcohol exposure between 1990 and 2017 and forecasts until 2030: a modelling study. Lancet 393 , 2493–2502 (2019).

Rehm, J. & Shield, K. D. Global burden of alcohol use disorders and alcohol liver disease. Biomedicines 7 , 99 (2019).

Paik, J. et al. The global burden of liver cancer (LC) and chronic liver diseases (CLD) is driven by non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and alcohol liver disease (ALD) [abstract GS008]. J. Hepatol. 77 (Suppl. 1), S5–S7 (2022).

GBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 396 , 1204–1222 (2020).

GBD 2017 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators.Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 392 , 1789–1858 (2018).

Ginès, P. et al. Population screening for liver fibrosis: toward early diagnosis and intervention for chronic liver diseases. Hepatology 75 , 219–228 (2022).

Alberts, C. J. et al. Worldwide prevalence of hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus among patients with cirrhosis at country, region, and global levels: a systematic review. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 7 , 724–735 (2022).

Eslam, M. et al. MAFLD: a consensus-driven proposed nomenclature for metabolic associated fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology 158 , 1999–2014.e1 (2020).

Ng, C. H., Huang, D. Q. & Nguyen, M. H. NAFLD versus MAFLD: prevalence, outcomes and implications of a change in name. Clin. Mol. Hepatol. https://doi.org/10.3350/cmh.2022.0070 (2022).

Noureddin, M. et al. Attribution of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis as an etiology of cirrhosis for clinical trials eligibility: recommendations from the multi-stakeholder liver forum. Gastroenterology 159 , 422–427.e1 (2020).

El-Serag, H. B. et al. Risk factors for cirrhosis in contemporary hepatology practices–findings from the Texas Hepatocellular Carcinoma Consortium Cohort. Gastroenterology 159 , 376–377 (2020).

Flemming, J. A., Djerboua, M., Groome, P. A., Booth, C. M. & Terrault, N. A. NAFLD and alcohol-associated liver disease will be responsible for almost all new diagnoses of cirrhosis in Canada by 2040. Hepatology 74 , 3330–3344 (2021).

Philip, G., Djerboua, M., Carlone, D. & Flemming, J. A. Validation of a hierarchical algorithm to define chronic liver disease and cirrhosis etiology in administrative healthcare data. PLoS ONE 15 , e0229218 (2020).

Sharma, S. A. et al. Toronto HCC risk index: a validated scoring system to predict 10-year risk of HCC in patients with cirrhosis. J. Hepatol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2017.07.033 (2017).

& Gonzalez-Chagolla, A. et al. Cirrhosis etiology trends in developing countries: transition from infectious to metabolic conditions. Report from a multicentric cohort in central Mexico. Lancet Reg. Health Am. 7 , 100151 (2022).

PubMed Google Scholar

Wong, R. J. & Singal, A. K. Trends in liver disease etiology among adults awaiting liver transplantation in the United States, 2014-2019. JAMA Netw. Open. 3 , e1920294 (2020).

Ward, Z. J. et al. Projected U.S. state-level prevalence of adult obesity and severe obesity. N. Engl. J. Med. 381 , 2440–2450 (2019).

World Health Organization. Global status report on alcohol and health 2018 (WHO, 2018).

Díaz, L. A. et al. Liver diseases in Latin America: current status, unmet needs, and opportunities for improvement. Curr. Treat. Options Gastroenterol. 20 , 261–278 (2022).

Gu, W. et al. Trends and the course of liver cirrhosis and its complications in Germany: Nationwide population-based study (2005 to 2018). Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 12 , 100240 (2022).

Hagström, H. et al. Etiologies and outcomes of cirrhosis in a large contemporary cohort. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 56 , 727–732 (2021).

Stroffolini, T. et al. Characteristics of liver cirrhosis in Italy: evidence for a decreasing role of HCV aetiology. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 38 , 68–72 (2017).

Stroffolini, T. et al. Characteristics of liver cirrhosis in Italy: results from a multicenter national study. Dig. Liver Dis. 36 , 56–60 (2004).

World Health Organization. Equity, social determinants and public health programmes (WHO, 2010).

World Health Organization. European action plan to reduce the harmful use of alcohol 2012–2020 (WHO, 2012).

Vento, S., Dzudzor, B., Cainelli, F. & Tachi, K. Liver cirrhosis in sub-Saharan Africa: neglected, yet important. Lancet Glob. Health 6 , e1060–e1061 (2018).

Mokdad, A. A. et al. Liver cirrhosis mortality in 187 countries between 1980 and 2010: a systematic analysis. BMC Med 12 , 145 (2014).

Yang, J. D. et al. Characteristics, management, and outcomes of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma in Africa: a multicountry observational study from the Africa Liver Cancer Consortium. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2 , 103–111 (2017).

Tailakh, M. A. et al. Liver cirrhosis, etiology and clinical characteristics disparities among minority population. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 24 , 1122–1128 (2022).

Elzouki, A. N. et al. Predicting mortality of patients with cirrhosis admitted to medical intensive care unit: an experience of a single tertiary center. Arab. J. Gastroenterol. 17 , 159–163 (2016).

Mukherjee, P. S. et al. Etiology and mode of presentation of chronic liver diseases in India: a multi centric study. PLoS ONE 12 , e0187033 (2017).

Alvi, H., Zuberi, B. F., Rasheed, T. & Ibrahim, M. A. Evaluation of endoscopic variceal band ligation sessions in obliteration of esophageal varices. Pak. J. Med. Sci. 36 , 37–41 (2020).

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Enomoto, H. et al. Transition in the etiology of liver cirrhosis in Japan: a nationwide survey. J. Gastroenterol. 55 , 353–362 (2020).

Jang, W. Y. et al. Changes in characteristics of patients with liver cirrhosis visiting a tertiary hospital over 15 years: a retrospective multi-center study in Korea. J. Korean Med. Sci. 35 , e233 (2020).

Xiong, J. et al. Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis-related liver cirrhosis is increasing in China: a ten-year retrospective study. Clinics 70 , 563–568 (2015).

Lu, S.-N. et al. Secular trends and geographic variations of hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus-associated hepatocellular carcinoma in Taiwan. Int. J. Cancer 119 , 1946–1952 (2006).

Schmidt, L. A. & Room, R. Alcohol and inequity in the process of development: contributions from ethnographic research. Int. J. Alcohol. Drug. Res. 1 , 41–55 (2013).

Wang, H., Ma, L., Yin, Q., Zhang, X. & Zhang, C. Prevalence of alcoholic liver disease and its association with socioeconomic status in north-eastern China. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 38 , 1035–1041 (2014).

Charatcharoenwitthaya, P., Liangpunsakul, S. & Piratvisuth, T. Alcohol-associated liver disease: East versus West. Clin. Liver Dis. 16 , 231–235 (2020).

Fan, J. G., Kim, S. U. & Wong, V. W. New trends on obesity and NAFLD in Asia. J. Hepatol. 67 , 862–873 (2017).

D’Amico, G., Garcia-Tsao, G. & Pagliaro, L. Natural history and prognostic indicators of survival in cirrhosis: a systematic review of 118 studies. J. Hepatol. 44 , 217–231 (2006).

Jepsen, P., Ott, P., Andersen, P. K., Sørensen, H. T. & Vilstrup, H. Clinical course of alcoholic liver cirrhosis: a Danish population-based cohort study. Hepatology 51 , 1675–1682 (2010).

Fleming, K. M., Aithal, G. P., Card, T. R. & West, J. The rate of decompensation and clinical progression of disease in people with cirrhosis: a cohort study. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 32 , 1343–1350 (2010).

Arroyo, V., Moreau, R. & Jalan, R. Acute-on-chronic liver failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 382 , 2137–2145 (2020).

Hernaez, R., Solà, E., Moreau, R. & Ginès, P. Acute-on-chronic liver failure: an update. Gut 66 , 541–553 (2017).

Sarin, S. K. et al. Acute-on-chronic liver failure: consensus recommendations of the Asian Pacific association for the study of the liver (APASL): an update. Hepatol. Int. 13 , 353–390 (2019).

Moreau, R. et al. Acute-on-chronic liver failure is a distinct syndrome that develops in patients with acute decompensation of cirrhosis. Gastroenterology 144 , 1426–1437.e9 (2013).

O’Leary, J. G. et al. NACSELD acute-on-chronic liver failure (NACSELD-ACLF) score predicts 30-day survival in hospitalized patients with cirrhosis. Hepatology 67 , 2367–2374 (2018).

Arroyo, V. et al. Acute-on-chronic liver failure in cirrhosis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2 , 16041 (2016).

Mezzano, G. et al. Global burden of disease: acute-on-chronic liver failure, a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gut 71 , 148–155 (2022).

Karlsen, T. H. et al. The EASL-Lancet Liver Commission: protecting the next generation of Europeans against liver disease complications and premature mortality. Lancet 399 , 61–116 (2022).

GBD 2019 Demographics Collaborators.Global age-sex-specific fertility, mortality, healthy life expectancy (HALE), and population estimates in 204 countries and territories, 1950–2019: a comprehensive demographic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 396 , 1160–1203 (2020).

Adams, L. A. et al. The natural history of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a population-based cohort study. Gastroenterology 129 , 113–121 (2005).

Huang, D. et al. Shared mechanisms between cardiovascular disease and NAFLD. Semin. Liver Dis. https://doi.org/10.1055/a-1930-6658 (2022).

Younossi, Z. M. et al. Nonalcoholic steatofibrosis independently predicts mortality in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatol. Commun. 1 , 421–428 (2017).

Estes, C. et al. Modelling NAFLD disease burden in four Asian regions – 2019-2030. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 51 , 801–811 (2020).

Estes, C. et al. Modeling NAFLD disease burden in China, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Spain, United Kingdom, and United States for the period 2016-2030. J. Hepatol. 69 , 896–904 (2018).

Razavi-Shearer, D. et al. The disease burden of hepatitis B and hepatitis C from 2015 to 2030: the long and winding road [abstract OS050]. J. Hepatol. 77 (Suppl. 1), S43 (2022).

Julien, J., Ayer, T., Bethea, E. D., Tapper, E. B. & Chhatwal, J. Projected prevalence and mortality associated with alcohol-related liver disease in the USA, 2019-40: a modelling study. Lancet Public. Health 5 , e316–e323 (2020).

Hsu, W. F. et al. Hepatitis C virus eradication decreases the risks of liver cirrhosis and cirrhosis-related complications (Taiwanese chronic hepatitis C cohort). J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 36 , 2884–2892 (2021).

Sanyal, A. J. et al. Cirrhosis regression is associated with improved clinical outcomes in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.32204 (2021).

Xie, Y. D., Feng, B., Gao, Y. & Wei, L. Effect of abstinence from alcohol on survival of patients with alcoholic cirrhosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hepatol. Res. 44 , 436–449 (2014).

Chang, T. T. et al. Long-term entecavir therapy results in the reversal of fibrosis/cirrhosis and continued histological improvement in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology 52 , 886–893 (2010).

Cox, A. L. et al. Progress towards elimination goals for viral hepatitis. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 17 , 533–542 (2020).

Tergast, T. L. et al. Updated epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infections and implications for hepatitis C virus elimination in Germany. J. Viral Hepat. 29 , 536–542 (2022).

Kondili, L. A. et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on hepatitis B and C elimination: an EASL survey. JHEP Rep. 4 , 100531 (2022).

GBD 2019 Hepatiitis B Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of hepatitis B, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 7 , 796–829 (2022).

Ye, Q. et al. Substantial gaps in evaluation and treatment of patients with hepatitis B in the US. J. Hepatol. 76 , 63–74 (2022).

Le, M. H. et al. Chronic hepatitis B prevalence among foreign-born and U.S.-born adults in the United States, 1999-2016. Hepatology 71 , 431–443 (2020).

Julien, J. et al. Effect of increased alcohol consumption during COVID-19 pandemic on alcohol-associated liver disease: a modeling study. Hepatology 75 , 1480–1490 (2022).

Bittermann, T., Mahmud, N. & Abt, P. Trends in liver transplantation for acute alcohol-associated hepatitis during the COVID-19 pandemic in the US. JAMA Netw. Open. 4 , e2118713 (2021).

Toyoda, H., Huang, D. Q., Le, M. H. & Nguyen, M. H. Liver care and surveillance: the global impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Hepatol. Commun. 4 , 1751–1757 (2020).

Tan, E. X.-X. Impact of COVID-19 on liver transplantation in Hong Kong and Singapore: a modelling study. Lancet Reg. Health West. Pac. 16 , 100262 (2021).

Lee, B. P., Dodge, J. L., Leventhal, A. & Terrault, N. A. Retail alcohol and tobacco sales during COVID-19. Ann. Intern. Med. 174 , 1027–1029 (2021).

White, A. M., Castle, I.-J. P., Powell, P. A., Hingson, R. W. & Koob, G. F. Alcohol-related deaths during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2022.4308 (2022).

Hussain, A. et al. Decompensated cirrhosis is the commonest presentation for NAFLD patients undergoing liver transplant assessment. Clin. Med. 20 , 313–318 (2020).

Trebicka, J. et al. The PREDICT study uncovers three clinical courses of acutely decompensated cirrhosis that have distinct pathophysiology. J. Hepatol. 73 , 842–854 (2020).

Lee, B. P., Dodge, J. L. & Terrault, N. A. Geographic density of gastroenterologists is associated with decreased mortality from alcohol-associated liver disease. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2022.07.020 (2022).

Oluyomi, A. O., El-Serag, H. B., Olayode, A. & Thrift, A. P. Neighborhood-level factors contribute to disparities in hepatocellular carcinoma incidence in Texas. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2022.06.031 (2022).

de Franchis, R., Bosch, J., Garcia-Tsao, G., Reiberger, T. & Ripoll, C. Baveno VII – Renewing consensus in portal hypertension. J. Hepatol. 76 , 959–974 (2022).

European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Liver transplantation. J. Hepatol. 64 , 433–485 (2016).

Lucey, M. R. et al. Long-term management of the successful adult liver transplant: 2012 practice guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the American Society of Transplantation. Liver Transpl. 19 , 3–26 (2013).

Sharpton, S. R. et al. Gut metagenome-derived signature predicts hepatic decompensation and mortality in NAFLD-related cirrhosis. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 56 , 1475–1485 (2022).

Lazarus, J. V. et al. Advancing the global public health agenda for NAFLD: a consensus statement. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41575-021-00523-4 (2021).

Díaz, L. A. et al. The establishment of public health policies and the burden of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in the Americas. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 7 , 552–559 (2022).

Labenz, C. et al. Structured early detection of asymptomatic liver cirrhosis: results of the population-based liver screening program SEAL. J. Hepatol. 77 , 695–701 (2022).

Kanwal, F. et al. Clinical care pathway for the risk stratification and management of patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology 161 , 1657–1669 (2021).

Rozenberg-Ben-Dror, K. et al. Improving quality of hepatitis B care in the Veteran’s Health Administration. Clin. liver Dis. 19 , 213–218 (2022).

Paik, J. M., Golabi, P., Younossi, Y., Mishra, A. & Younossi, Z. M. Changes in the global burden of chronic liver diseases from 2012 to 2017: the growing impact of NAFLD. Hepatology 72 , 1605–1616 (2020).

Nehra, M. S. et al. Use of administrative claims data for identifying patients with cirrhosis. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 47 , e50–e54 (2013).

Hayward, K. L. et al. ICD-10-AM codes for cirrhosis and related complications: key performance considerations for population and healthcare studies. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 7 , e000485 (2020).

Ramrakhiani, N. S. et al. Validity of international classification of diseases, tenth revision, codes for cirrhosis. Dig. Dis. 39 , 243–246 (2021).

Mapakshi, S., Kramer, J. R., Richardson, P., El-Serag, H. B. & Kanwal, F. Positive predictive value of international classification of diseases, 10th revision, codes for cirrhosis and its related complications. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 16 , 1677–1678 (2018).

Bengtsson, B., Askling, J., Ludvigsson, J. F. & Hagström, H. Validity of administrative codes associated with cirrhosis in Sweden. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 55 , 1205–1210 (2020).

Shearer, J. E. et al. Systematic review: development of a consensus code set to identify cirrhosis in electronic health records. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 55 , 645–657 (2022).

Ratib, S., West, J., Crooks, C. J. & Fleming, K. M. Diagnosis of liver cirrhosis in England, a cohort study, 1998-2009: a comparison with cancer. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 109 , 190–198 (2014).

Thygesen, S. K., Christiansen, C. F., Christensen, S., Lash, T. L. & Sørensen, H. T. The predictive value of ICD-10 diagnostic coding used to assess Charlson comorbidity index conditions in the population-based Danish National Registry of Patients. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 11 , 83 (2011).

Kramer, J. R. et al. The validity of viral hepatitis and chronic liver disease diagnoses in Veterans Affairs Administrative databases. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 27 , 274–282 (2008).

Goldberg, D., Lewis, J., Halpern, S., Weiner, M. & Lo Re, V. 3rd Validation of three coding algorithms to identify patients with end-stage liver disease in an administrative database. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug. Saf. 21 , 765–769 (2012).

Kim, D., Alshuwaykh, O., Dennis, B. B., Cholankeril, G. & Ahmed, A. Trends in etiology-based mortality from chronic liver disease before and during COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 20 , 2307–2316.e3 (2022).

Pollard, M. S., Tucker, J. S. & Green, H. D. Jr. Changes in adult alcohol use and consequences during the COVID-19 pandemic in the US. JAMA Netw. Open. 3 , e2022942 (2020).

The Lancet Gastroenterology Hepatology. Drinking alone: COVID-19, lockdown, and alcohol-related harm. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 5 , 625 (2020).

NANOS Research. COVID-19 and increased alcohol consumption: NANOS poll summary report (Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction, 2020).

Vanderbruggen, N. et al. Self-reported alcohol, tobacco, and cannabis use during COVID-19 lockdown measures: results from a web-based survey. Eur. Addict. Res. 26 , 309–315 (2020).

Sidor, A. & Rzymski, P. Dietary choices and habits during COVID-19 lockdown: experience from Poland. Nutrients 12 , 1657 (2020).

Ge, J., Pletcher, M. J. & Lai, J. C. Outcomes of SARS-CoV-2 infection in patients with chronic liver disease and cirrhosis: a national COVID cohort collaborative study. Gastroenterology 161 , 1487–1501.e5 (2021).

Mahmud, N., Hubbard, R. A., Kaplan, D. E. & Serper, M. Declining cirrhosis hospitalizations in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic: a national cohort study. Gastroenterology 159 , 1134–1136.e3 (2020).

Tapper, E. B. & Asrani, S. K. The COVID-19 pandemic will have a long-lasting impact on the quality of cirrhosis care. J. Hepatol. 73 , 441–445 (2020).

Blach, S. et al. Impact of COVID-19 on global HCV elimination efforts. J. Hepatol. 74 , 31–36 (2021).

Download references

Acknowledgements

R.L. receives funding support from NCATS (5UL1TR001442), NIDDK (U01DK061734, U01DK130190, R01DK106419, R01DK121378, R01DK124318, P30DK120515), NHLBI (P01HL147835) and NIAAA (U01AA029019). D.Q.H. receives funding support from the Singapore Ministry of Health’s NMRC Research Training Fellowship (MOH-000595-01). M.A. acknowledges partial support from the Chilean government through the Fondo Nacional de Desarrollo Científico y Tecnológico (FONDECYT grant 1191145).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

NAFLD Research Center, Division of Gastroenterology, University of California at San Diego, San Diego, CA, USA

Daniel Q. Huang & Rohit Loomba

Department of Medicine, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore, Singapore

Daniel Q. Huang

Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Department of Medicine, National University Health System, Singapore, Singapore

Division of Gastrointestinal and Liver Diseases, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, USA

Norah A. Terrault

Department of Hepatology & Gastroenterology, Campus Virchow-Klinikum and Campus Charité Mitte, Charité Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Berlin, Germany

Frank Tacke

Gastro Unit, Copenhagen University Hospital, Hvidovre, Denmark

Lise Lotte Gluud

Department of Clinical Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark

Departamento de Gastroenterologia, Escuela de Medicina, Pontificia Universidad Catolica de Chile, Santiago, Chile

Marco Arrese

Centro de Envejecimiento Y Regeneración (CARE), Facultad de Ciencias Biológicas, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Santiago, Chile

Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Department of Medical Sciences, University of Turin, Turin, Italy

Elisabetta Bugianesi

Division of Epidemiology, Department of Family Medicine and Public Health, University of California at San Diego, San Diego, CA, USA

Rohit Loomba

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

All authors contributed to all aspects of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Rohit Loomba .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

D.Q.H. has served as an advisory board member for Eisai and Gilead. N.A.T. receives institutional grant support from DURECT Corporation, Eiger Pharmaceuticals, Gilead Sciences, Glaxo-Smith-Kline, Helio Health and Roche-Genentech. F.T. serves as a consultant to Abbvie, Alnylam, Boehringer-Ingelheim, CSL Behring, Falk, Gilead, Intercept, Inventiva, Ionis, Novartis, Novo Nordisk and Pfizer. His institute has received research grants from Allergan, Bristol Myers Squibb, Gilead and Inventiva. L.L.G. serves as a consultant to Novo Nordisk and Pfizer, and her institutes have received research grants from Alexion, Gilead, Novo Nordisk, Sobi Int. and Vingmed. M.A. receives support from the Chilean government through the Fondo Nacional De Ciencia y Tecnología de Chile (FONDECYT no. 1191145) and the Comisión Nacional de Investigación, Ciencia y Tecnología (CONICYT, AFB170005, CARE, Chile, UC). E.B. serves as a consultant to AstraZeneca, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Gilead, Intercept, Inventiva, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Merck, MSD and Pfizer. Her institute has received a research grant from Gilead. R.L. serves as a consultant to 89 Bio, Aardvark Therapeutics, Altimmune, Anylam/Regeneron, Amgen, Arrowhead Pharmaceuticals, AstraZeneca, Bristol Myers Squibb, CohBar, Eli Lilly, Galmed, Gilead, Glympse bio, Hightide, Inipharma, Intercept, Inventiva, Ionis, Janssen, Madrigal, Metacrine, NGM Biopharmaceuticals, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Merck, Pfizer, Sagimet, Theratechnologies, Terns Pharmaceuticals and Viking Therapeutics. In addition his institutes have received research grants from Arrowhead Pharmaceuticals, Astrazeneca, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Galectin Therapeutics, Galmed Pharmaceuticals, Gilead, Intercept, Hanmi, Intercept, Inventiva, Ionis, Janssen, Madrigal Pharmaceuticals, Merck, NGM Biopharmaceuticals, Novo Nordisk, Merck, Pfizer, Sonic Incytes and Terns Pharmaceuticals. He is also a co-founder of LipoNexus.

Peer review

Peer review information.

Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology thanks M.-L. Yu, who co-reviewed with P.-Y. Hsu, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Review criteria PubMed was searched from inception to June 2022 using the terms ‘cirrhosis’, ‘end-stage liver disease’ and ‘liver cirrhosis’ without language restrictions. Guidelines, original articles and reviews were evaluated. Data for the global and regional number and age-adjusted rate of deaths estimated in the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) Study 2019 were obtained from the GBD Results Tool 27 . The GBD Study was used to identify trends in the mortality rates of cirrhosis 112 , but not temporal trends in the prevalence of the aetiologies of cirrhosis, as limited data on these trends were available within the GBD framework. Individual country-specific and region-specific studies were, therefore, selected to provide data from diverse geographical locations on temporal trends in the prevalence of the aetiologies of cirrhosis. When multiple studies originating from the same country were available, studies that provided data for temporal trends in aetiologies of cirrhosis were preferentially selected.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information, rights and permissions.

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Huang, D.Q., Terrault, N.A., Tacke, F. et al. Global epidemiology of cirrhosis — aetiology, trends and predictions. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 20 , 388–398 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41575-023-00759-2

Download citation

Accepted : 22 February 2023

Published : 28 March 2023

Issue Date : June 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41575-023-00759-2

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

A novel network pharmacology strategy to decode mechanism of wuling powder in treating liver cirrhosis.

Chinese Medicine (2024)