- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Guest Essay

School Is for Social Mobility

By John N. Friedman

Mr. Friedman is an economist at Brown whose work focuses on how to use big data to improve life outcomes.

America is often hailed as a land of opportunity, a place where all children, no matter their family background, have the chance to succeed. Data measuring how low-income children tend to fare in adulthood, however, suggest this may be more myth than reality.

Less than one in 13 children born into poverty in the United States will go on to hold a high-income job in adulthood; the odds are far longer for Black men born into poverty, at one in 40 .

Education is the solution to this lack of mobility. There are still many ways in which the current education system generates its own inequities, and many of these have been exacerbated by Covid-19 closures. But the pandemic also revealed a potential path forward by galvanizing support for education funding at levels rarely seen before. With the right level of investment, education can not only provide more pathways out of poverty for individuals, but also restore the equality of opportunity that is supposed to lie at America’s core.

It is certainly not a new idea that education can change a child’s life trajectory. Almost everyone has some formative school memory — a teacher with whom everything made sense, an art project that opened new doors or a sports championship that bonded teammates for life.

But what is new is the torrent of research studies using “big data” to show the power of education for shaping children’s trajectories, especially over the long term. In one study, for example, my co-authors and I found that students who were randomly assigned to higher-quality classrooms earned substantially more 20 years later, about $320,000 over their lifetimes. And it’s not only the early grades that matter; research suggests the quality of education in later grades may be even more important for long-term outcomes, as children’s brains don’t lock in key neural pathways for advanced reasoning skills until well into their teenage years.

Education changes lives in ways that go far beyond economic gains. The data show clearly that children who get better schooling are healthier and happier adults, more civically engaged and less likely to commit crimes . Schools not only teach students academic skills but also noncognitive skills, like grit and teamwork, which are increasingly important for generating social mobility. Even the friendships that students form at school can be life-altering forces for social mobility, because children who grow up in more socially connected communities are much more likely to rise up out of poverty.

We are having trouble retrieving the article content.

Please enable JavaScript in your browser settings.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access. If you are in Reader mode please exit and log into your Times account, or subscribe for all of The Times.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access.

Already a subscriber? Log in .

Want all of The Times? Subscribe .

Thirteen Economic Facts about Social Mobility and the Role of Education

- Thirteen Economic Facts About Social Mobility and the Role of Education - Full Policy Memo

Subscribe to the Economic Studies Bulletin

Michael greenstone, adam looney, jeremy patashnik, and muxin yu, the hamilton project mgaljpamythp michael greenstone, adam looney, jeremy patashnik, and muxin yu, the hamilton project.

June 26, 2013

- 22 min read

This Hamilton Project policy memo provides thirteen economic facts on the growth of income inequality and its relationship to social mobility in America; on the growing divide in educational opportunities and outcomes for high- and low-income students; and on the pivotal role education can play in increasing the ability of low-income Americans to move up the income ladder.

Read the full introduction »

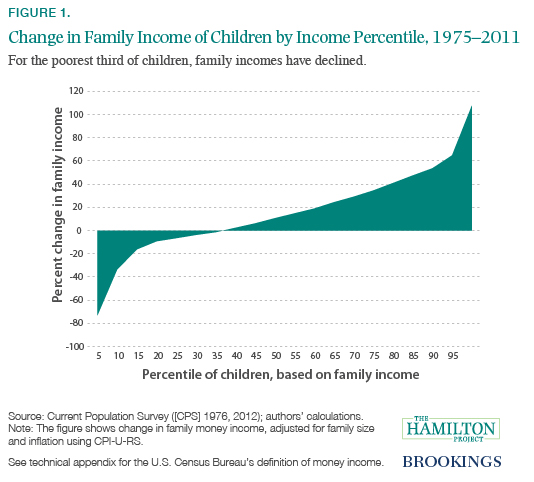

It is well known that the income divide in the United States has increased substantially over the last few decades, a trend that is particularly true for families with children. In fact, according to Census Bureau data, more than one-third of children today are raised in families with lower incomes than comparable children thirty-five years ago. This sustained erosion of income among such a broad group of children is without precedent in recent American history. Over the same period, children living in the highest 5 percent of the family-income distribution have seen their families’ incomes double.

What is less well known, however, is that mounting evidence hints that the forces behind these divergent experiences are threatening the upward mobility of the youngest Americans, and that inequality of income for one generation may mean inequality of opportunity for the next. It is too early to say for certain whether the rise in income inequality over the past few decades has caused a fall in social mobility of the poor and those in the middle class—the first generation of Americans to grow up under this inequality is, on average, in high school—but the early signs are troubling.

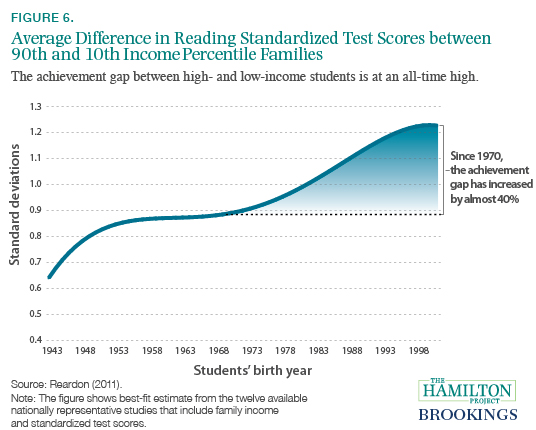

Investments in education and skills, which are factors that increasingly determine outcomes in the job market, are becoming more stratified by family income. As income inequality has increased, wealthier parents are able to invest more in their children’s education and enrichment, increasing the already sizable difference in investment from those at the other end of the earnings distribution. This disparity has real and measurable consequences for the current generation of American children. Although cognitive tests of ability show little difference between children of high- and low-income parents in the first years of their lives, large and persistent differences start emerging before kindergarten. Among older children, evidence suggests that the gap between high- and low-income primary and secondary-school students has increased by almost 40 percent over the past thirty years.

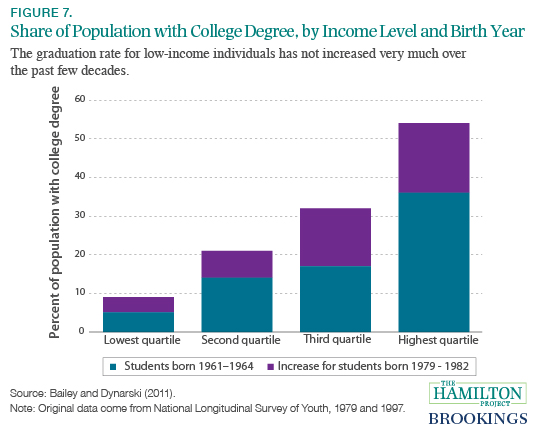

These differences persist and widen into young adulthood and beyond. Just as the gap in K–12 test scores between high and low-income students is growing, the difference in college graduation rates between the rich and the poor is also growing. Although the college graduation rate among the poorest households increased by about 4 percentage points between those born in the early 1960s and those born in the early 1980s, over this same period, the graduation rate increased by almost 20 percentage points for the wealthiest households.

Given how important education and, in particular, a college degree are in the labor market, these trends give rise to concerns that last generation’s inequities will be perpetuated into the next generation and opportunities for upward social mobility will be diminished. The emphasis that American society places on upward mobility makes this alarming in and of itself. In addition, low levels of social mobility may ultimately shift public support toward policies to address such inequities, instead of toward policies intended to promote economic growth.

While the urgency of finding solutions to this challenge requires rethinking a broad range of social and economic policies, we believe that any successful approach will necessitate increasing the skills and human capital of Americans. Decades of research demonstrate that policies that improve the quality of and expand access to early-childhood, K–12, and higher education can be effective at ameliorating these stark differences in economic opportunities across households.

Indeed, making it easier and more affordable for low-income students to attend college has long been a vehicle for upward mobility. Over the past fifty years, policies that have increased access to higher education, from the GI Bill to student aid, have not only helped lift thousands of Americans into the middle class and beyond, but also have boosted the productivity, innovation, and resources of the American economy.

Fortunately, researchers are making rapid progress in identifying new approaches that complement or improve on long-standing federal aid programs to boost college attendance and completion among lower-income students. These new interventions, which include high school and college mentoring, targeted informational interventions, and behavioral approaches to nudge students into better outcomes, could form the basis of important new policies that aim to steer more students toward college.

A founding principle of The Hamilton Project’s economic strategy is that long-term prosperity is best achieved by fostering economic growth and broad participation in that growth. This principle is particularly relevant in the context of social mobility, wherein broad participation in growth can contribute to further growth by providing families with the ability to invest in their children and communities, optimism that their hard work and efforts will lead to success for them and their children, and openness to innovation and change that lead to new sources of economic growth.

In this spirit, we offer our “Thirteen Economic Facts about Social Mobility and the Role of Education.” In chapter 1, we examine the very different changes in income between American families at opposite ends of the income distribution over the last thirty-five years and the seemingly dominant role that a child’s family income plays in determining his or her future economic outcomes. In chapter 2, we provide evidence on the growing divide in the United States in educational opportunities and outcomes based on family income. In chapter 3, we explore the great potential of education to increase upward mobility for all Americans, with a special focus on what we know about how to increase college attendance and completion for low-income students.

Chapter 1: Inequality Is Rising against a Background of Low Social Mobility

Central to the American ethos is the notion that it is possible to start out poor and become more prosperous: that hard work—not simply the circumstances you were born into—offers real prospects for success. But there is a growing gap between families at the top and bottom of the income distribution, raising concerns about the ability of today’s disadvantaged to work their way up the economic ladder.

1. Family incomes have declined for a third of American children over the past few decades.

Although family income has increased by an average of 37 percent between 1975 and 2011, family incomes have actually declined for the poorest third of children.

Figure 1 illustrates the diverging fortunes of children based on their family’s income, as measured by the U.S. Census Bureau. Children in families at the top of the income distribution have experienced sizable gains in their families’ incomes and resources since 1975. Children living in the top 5 percent of families, for instance, have seen a doubling of their families’ incomes. But such gains have been more modest for children in the middle of the distribution, and children living in lower-income families have experienced outright declines in incomes. In fact, in 2011 the bottom 35 percent of children lived in families with lower reported incomes than comparable children thirty-six years earlier.

Because of widening disparities in the earnings of their parents and changes in family structure—particularly the increase in single-parent families—the family resources available to lesswell- off children are falling behind those available to their higher-income peers.

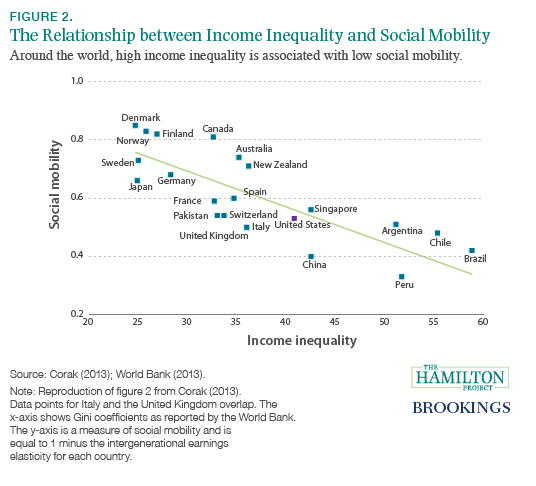

2. Countries with high income inequality have low social mobility.

Many are concerned that rising income inequality will lead to declining social mobility. Figure 2, recently coined “The Great Gatsby Curve,” takes data from several countries at a single point in time to show the relationship between inequality and immobility. Inequality is measured using Gini coefficients, a common metric that economists use to determine how much of a nation’s income is concentrated among the wealthy; social mobility is measured using intergenerational earnings elasticity, an indicator of how much children’s future earnings depend on the earnings of their parents.

Although, as the figure shows, higher levels of inequality are positively correlated with reductions in social mobility, we do not know whether inequality causes reductions in mobility. After all, there are many important factors that vary between countries that might explain this relationship. Nonetheless, figure 2 represents a provocative observation with potentially important policy ramifications.

What figure 2 makes clear is that, although most people think of the United States as the land of opportunity—where hard workers from any background can prosper—the reality is far less encouraging. In fact, in terms of both income inequality and social mobility, the United States is in the middle of the pack when compared to other nations, most of which are democratic countries with market economies.

3. Upward social mobility is limited in the United States.

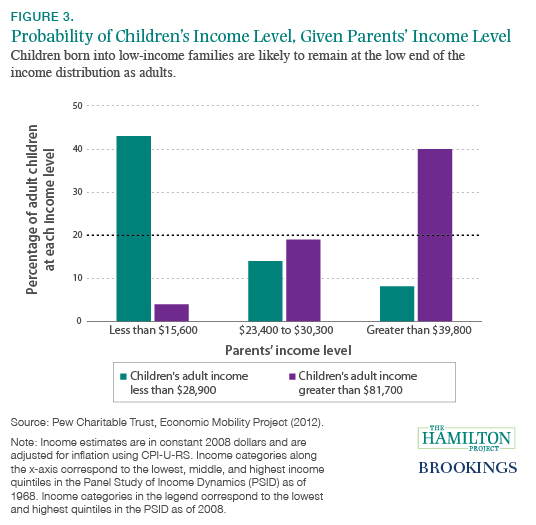

While social mobility and economic opportunity are important aspects of the American ethos, the data suggest they are more myth than reality. In fact, a child’s family income plays a dominant role in determining his or her future income, and those who start out poor are likely to remain poor.

Figure 3 shows the chances that a child’s future earnings will place him in the lowest quintile (that is, the bottom 20 percent of the earnings distribution, shown by the green bars) or the highest quintile (that is, the top 20 percent of the distribution, purple bars) depending on where his parents fell in the distribution (from left to right on the figure, the lowest, middle, and highest quintiles). In a completely mobile society, all children would have the same likelihood of ending up in any part of the income distribution; in this case, all bars on figure 3 would be at 20 percent, denoted by the bold line.

The figure demonstrates that children of well-off families are disproportionately likely to stay well off and children of poor families are very likely to remain poor. For example, a child born to parents with income in the lowest quintile is more than ten times more likely to end up in the lowest quintile than the highest as an adult (43 percent versus 4 percent). And, a child born to parents in the highest quintile is five times more likely to end up in the highest quintile than the lowest (40 percent versus 8 percent). These results run counter to the historic vision of the United States as a land of equal opportunity.

Chapter 2: The United States Is Experiencing a Growing Divide in Educational Investments and Outcomes Based on Family Income

Although children of high- and low-income families are born with similar abilities, high-income parents are increasingly investing more in their children. As a result, the gap between high- and low-income students in K–12 test scores, college attendance and completion, and graduation rates is growing.

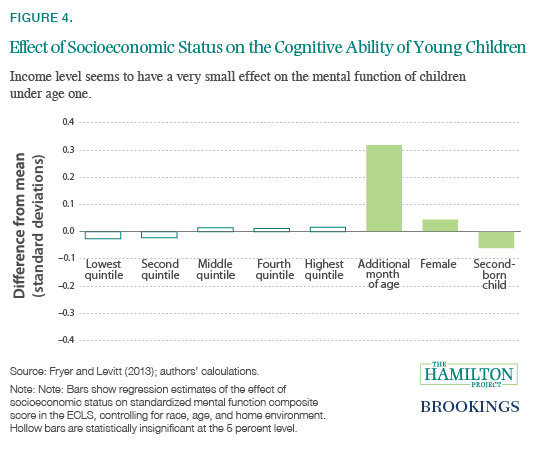

4. The children of high- and low-income families are born with similar abilities but different opportunities.

In examining the opportunity gap between high- and low-income children, it is important to begin at the beginning— birth. The evidence suggests that children of high- and low-income families start out with similar abilities but rapidly diverge in outcomes.

At the earliest ages, there is almost no difference in cognitive ability between high- and low-income individuals. Figure 4 shows the impact of a family’s socioeconomic status—a combination of income, education, and occupation—on the cognitive ability of infants between eight and twelve months of age, as measured in the Early Childhood Longitudinal Survey. Although it is obviously difficult to measure the cognitive ability of infants, this ECLS metric has been shown to be modestly predictive of IQ at age five (Fryer and Levitt 2013).

Controlling for age, number of siblings, race, and other environmental factors, the effects of socioeconomic status are small and statistically insignificant. A child born into a family in the highest socioeconomic quintile, for example, can expect to score only 0.02 standard deviations higher on a test of cognitive ability than an average child, while one born into a family in the lowest socioeconomic quintile can expect to score about 0.03 standard deviations lower—hardly a measurable difference and statistically insignificant. By contrast, other factors, such as age, gender, and birth order, have a greater impact on abilities at the earliest stages of life.

Despite similar starting points, by age four, children in the highest income quintile score, on average, in the 69th percentile on tests of literacy and mathematics, while children in the lowest income quintile score in the 34th and 32nd percentile, respectively (Waldfogel and Washbrook 2011). Research suggests that these differences arise largely due to factors related to a child’s home environment and family’s socioeconomic status (Fryer and Levitt 2004).

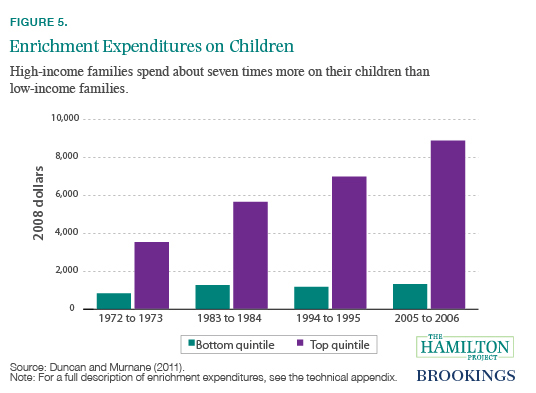

5. There is a widening gap between the investments that high- and low-income families make in their children.

Although we may all enter the world on similar footing, the deck is stacked against children born into low-income households. One significant consequence of growing income inequality is that, by historical standards, high-income households are spending much more on their children’s education than low-income households. Figure 5 shows enrichment expenditures—SAT prep, private tutors, computers, music lessons, and the like—by income level.

Over the past four decades, families at the top of the income ladder have increased spending in these areas dramatically, from just over $3,500 to nearly $9,000 per child per year (in constant 2008 dollars). By comparison, those at the bottom of the income distribution have increased their spending since the early 1970s from less than $850 to about $1,300. The difference is still stark: high-income families have gone from spending slightly more than four times as much as low-income families to nearly seven times more.

Parents of higher socioeconomic status invest not only more money in their children, but more time as well. On average, mothers with a college degree spend 4.5 more hours each week engaging with their children than mothers with only a high school diploma or less (Guryan, Hurst, and Kearney 2008). This means that, among other things, by age three, children of parents who are professionals have vocabularies that are 50 percent larger than those of children from working-class families, and 100 percent larger than those of children whose families receive welfare, disparities that some researchers ascribe to differences in how much parents engage and speak with their children. By the time they are three, children born to parents who are professionals have heard about 30 million more words than children born to parents who receive welfare (Hart and Risley 1995).

6. The achievement gap between high- and low-income students has increased.

Disparities in what parents can invest in their children—whether time or money—appear to have important consequences for children’s success in school. While many factors play a role in shaping scholastic achievement, family income is one of the most persistent and significant. In fact, the income achievement gap—the role that wealth plays in educational attainment—has been increasing over the past five decades. By comparing test results of children from families at the 90th income percentile to those of children from families at the 10th percentile, researchers have found that the gap has grown by about 40 percent over the past thirty years (Reardon 2011).

Figure 6 shows that the income achievement gap as estimated for students born in 2001 is over 1.2 standard deviations. To put this in perspective, according to the National Assessment of Educational Progress, an average student advances between 1.2 and 1.5 standard deviations between fourth and eighth grade. The achievement gap between high- and low-income students, then, is on par with the gap between eighth graders and fourth graders.

This growing test-score gap mirrors the diverging parental investments of high- and low-income families (figure 5). As with parental investment, the test scores of low-income students have shown modest gains over the past few decades, while those of high-income students have shown large increases. The gap between high- and low-income students, therefore, is not an instance of the poor doing worse while the wealthy are doing better; rather, it is that students from wealthier families are pulling away from their lower-income peers.

7. College graduation rates have increased sharply for wealthy students but stagnated for low-income students.

College graduation rates have increased dramatically over the past few decades, but most of these increases have been achieved by high-income Americans. Figure 7 shows the change in graduation rates for individuals born between 1961 and 1964 and those born between 1979 and 1982. The graduation rates are reported separately for children in each quartile of the income distribution.

In every income quartile, the proportion graduating from college increased, but the size of that increase varied considerably. While the highest income quartile saw an 18 percentage-point increase in the graduation rate between these birth cohorts, the lowest income quartile saw only a 4 percentage-point increase.

This graduation-rate gap may have important implications for social mobility and inequality. Given the importance of a college degree in today’s labor market, rising disparities in college completion portend rising disparities in outcomes in the future.

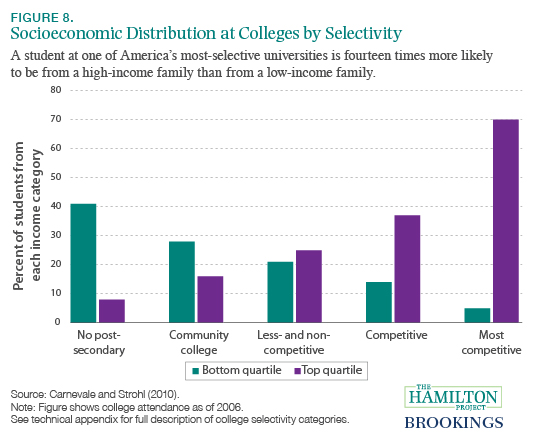

8. High-income families dominate enrollment at America’s selective colleges.

The gap between high- and low-income groups in college outcomes extends beyond college graduation rates. Students from higher-income families also apply to and enroll in moreselective colleges. Figure 8 reports the percent of students at more- and less-selective schools that come from families in the top and bottom quartiles of the socioeconomic status distribution (a combination of parental income, education, and occupation).

The figure demonstrates that the most-competitive colleges are attended almost entirely by students from higher–socioeconomic status households. Indeed, the more competitive the institution, the greater the percentage of the student body that comes from the top quartile, and the smaller the percentage from the bottom quartile. At institutions ranked as “most competitive”—those with more-selective admissions and that require high grades and SAT scores— the wealthiest students out-populate the poorest students by a margin of fourteen to one (Carnevale and Strohl 2010). By contrast, at institutions ranked as “less-competitive” and “noncompetitive,” the lowest–socioeconomic status students are over-represented.

Chapter 3: Education Can Play a Pivotal Role in Improving Social Mobility

Promoting increased social mobility requires reexamining a wide range of economic, health, social, and education policies. Higher education has always been a key way for poor Americans to find opportunities to transform their economic circumstances. In a time of rising inequality and low social mobility, improving the quality of and access to education has the potential to increase equality of opportunity for all Americans.

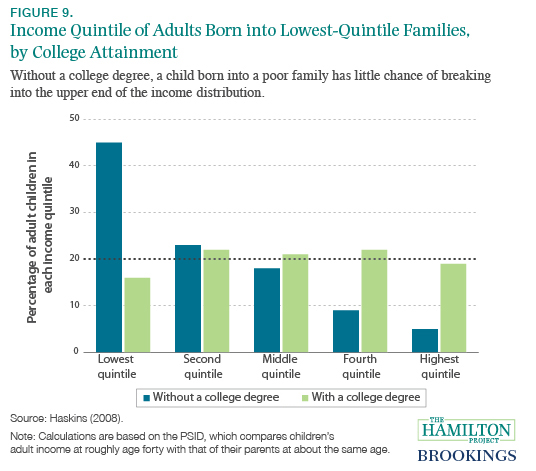

9. A college degree can be a ticket out of poverty.

The earnings of college graduates are much higher than for nongraduates, and that is especially true among people born into low-income families. Figure 9 shows the earnings outcomes for individuals born into the lowest quintile of the income distribution, depending on whether they earned a college degree. In a perfectly mobile society, an individual would have an equal chance of ending up in any of the five quintiles, and all the bars would be level with the bold line.

As the figure shows, however, without a college degree a child born into a family in the lowest quintile has a 45 percent chance of remaining in that quintile as an adult and only a 5 percent chance of moving into the highest quintile. On the other hand, children born into the lowest quintile who do earn a college degree have only a 16 percent chance of remaining in the lowest quintile and a 19 percent chance of breaking into the top quintile. In other words, a low-income individual without a college degree will very likely remain in the lower part of the earnings distribution, whereas a low-income individual with a college degree could just as easily land in any income quintile—including the highest.

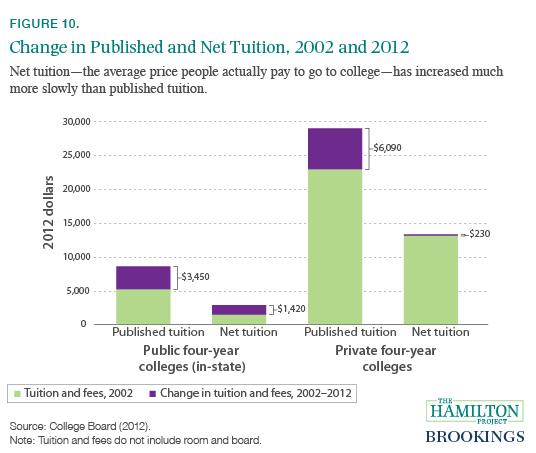

10. The sticker price of college has increased significantly in the past decade, but the actual price for many lower- and middle-income students has not.

In the past decade, increases in the sticker price of attending college have made going to college appear, for some, prohibitively expensive. Published tuition and fees for the 2012–13 academic year are projected to average $26,060 for private four-year institutions, and $8,860 in-state for public four-year institutions (College Board 2012). But before allowing this sticker price to be a deterrent, students must look deeper to learn whether those costs apply to them. Looking at net tuition—the price that the average student actually pays after financial aid—the picture is very different.

Because of increases in federal, state, and college-provided financial aid, not only is average net tuition much lower than average published tuition, but it has also increased at a much lower rate than published tuition in the past ten years. As seen in figure 10, net in-state tuition and fees at public four-year colleges have only increased by an average of $1,420 since 2002, which is less than half of the increase in the published rate. Although published tuition at private four-year colleges has increased by an average of $6,090 since 2002, net tuition has only increased by $230. In fact, the projected average net tuition at private four-year colleges for the academic year 2012–13 is 3.7 percent lower than the average net tuition in 2007–08 and lower than all five academic years between 2004–05 and 2008–09 (College Board 2012).

For many households, high costs of tuition are a burden. Once families and students have a sense of what financial aid they are eligible for, they can get a more accurate idea of the actual price tag for tuition. For each student, the net cost is the important consideration when making educational decisions.

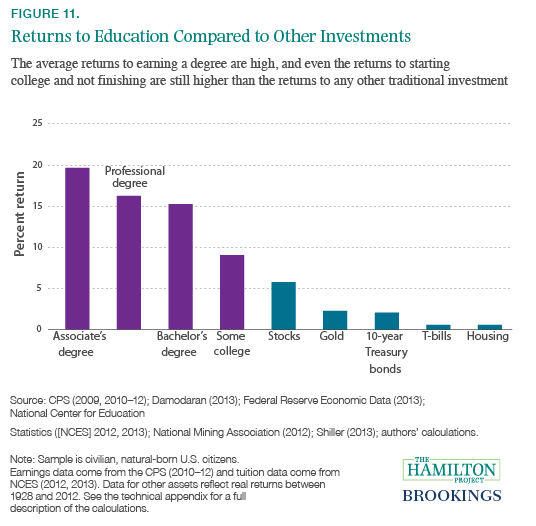

11. Few investments yield as high a return as a college degree.

Obtaining a college degree can significantly boost one’s income. Over the past three years, individuals between the ages of thirty and fifty who graduated from high school but did not attend college could expect to earn less than $30,000 per year. Those whose highest level of educational attainment was a bachelor’s degree earned just under $60,000 per year, and those with an advanced degree earned over $80,000.

But even individuals who attend college and do not obtain a degree still see an increase in their annual earnings. Those who leave college before receiving a credential or degree earn about $7,000 per year more than those with only a high school diploma, and individuals holding an associate’s degree earn over $10,000 more.

Higher education is one of the best investments an individual can make. As shown in figure 11, the returns to earning an associate’s, professional, or bachelor’s degree exceed 15 percent, and even the average return to attending some college for those who do not earn a degree is 9 percent. In comparison, the average return to an investment in the stock market is a little over 5 percent; gold, ten-year Treasury bonds, T-bills, and housing are 3 percent or less.

Although the return to an associate’s degree really stands out, this high return partially reflects the lower cost of an associate’s degree rather than a major boost to long-run earnings. Over a lifetime, the earnings of an associate’s degree recipient are roughly $170,000 higher than those of a high school graduate, while the earnings of a bachelor’s degree holder are $570,000 more than those of a high school graduate.

While it is likely that college graduates have different aptitudes and ambitions that might affect earnings and thus the resulting economic returns, a large body of academic research suggests there is a strong causal relationship between increases in education and increases in earnings (Card 2001).

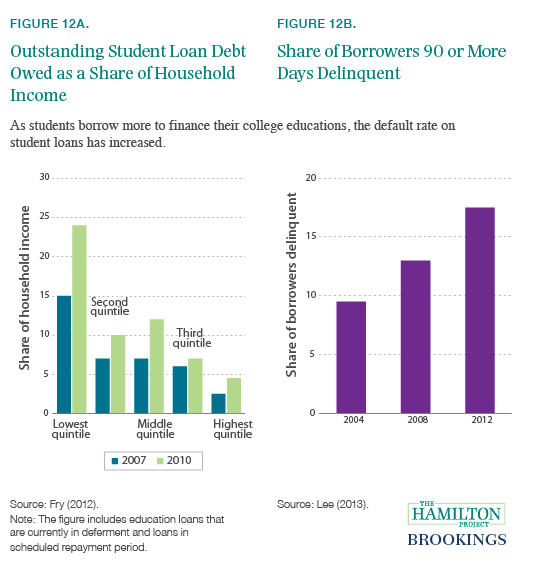

12. Students are borrowing more to attend college—and defaulting more frequently on their loans.

Over the past decade, the volume and frequency of student loans have increased significantly. The share of twenty-five-year-olds with student debt has risen by about 15 percentage points since 2004, and the amount of student debt incurred by those under the age of thirty has more than doubled (Lee 2013).

Despite these increases, the majority of students appear to borrow prudently. About 90 percent have loan balances less than $50,000, and 40 percent have balances under $10,000 (Fry 2012). Given that a college graduate can expect to earn, on average, about $30,000 more per year than a high school graduate over the course of his or her life, the returns to college appear to warrant the cost of student loans for most students.

Still, recent trends in student loans raise questions and concerns that merit further investigation. For one, it is unclear why student debt is increasing at its current trajectory. Neither college enrollment nor net college tuition has risen dramatically enough over the past decade to explain the rapid upsurge. Second, even though most students have a relatively low total loan balance, the default rate has increased significantly over the past decade: the share of those more than ninety days delinquent rose from under 10 percent in 2004 to about 18 percent in 2012 (figure 12b). While the returns to investments in college remain high, it will be important for policymakers to better understand why debt and delinquency rates have increased over the past decade.

13. New low-cost interventions can encourage more low-income students to attend, remain enrolled in, and increase economic diversity at even top colleges.

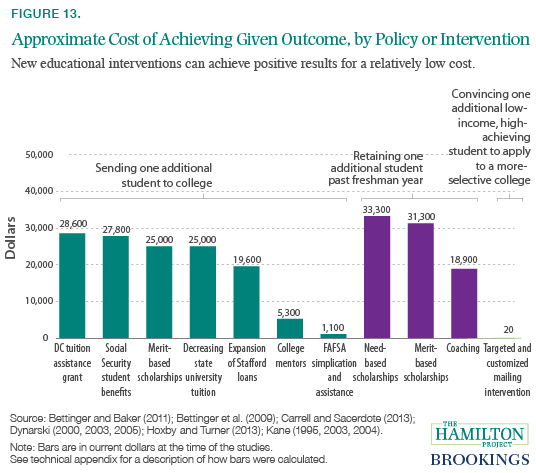

To promote social mobility, enabling more low- and middle-income students to pay for college with federal grants is one of the most important goals that policymakers can pursue. For the past several decades, the main tools for achieving this goal have been Pell grants, Stafford loans, or merit-based aid such as the state of Georgia’s HOPE Scholarship. Researchers estimate that, depending on the exact program, the effect of $1,000 of college aid is an increase of 3 to 6 percentage points in college enrollment (Deming and Dynarski 2009). As figure 13 shows, this translates into a total cost of between $20,000 and $30,000 to send one additional student to college through these aid programs. To put this in context, the average difference in earnings between a college graduate and a high school graduate is almost $30,000 per year, so these programs are likely to be beneficial on net.

Figure 13 also reports on new, low-cost interventions that can complement federal and state aid programs to send more kids to college and to better schools, and to convince them to stay in college once they get there. One study finds that simplifying and assisting low-income students in the financial aid application process increases college enrollment by about 8 percentage points, and costs less than $100 per student (Bettinger et al. 2009). And, on a per student basis, employing mentors to coach students on the value of staying in college beyond their freshman years is $10,000 less expensive than need- or merit-based scholarships (Bettinger and Baker 2011).

Another study found that mailing high-achieving, low-income students personalized information on their college options nudged those students to apply to better schools. At a cost of only $6 per student contacted, this intervention increased low-income students’ applications to selective schools by more than 30 percentage points (Hoxby and Turner 2013).

Related Content

Ron Haskins, James Kemple

May 14, 2009

Michael Greenstone and Adam Looney, The Hamilton Project

June 21, 2013

Eleanor Krause, Isabel V. Sawhill

June 5, 2018

Related Books

Nora Claudia Lustig

September 1, 1995

Nicolas P. Retsinas, Eric S. Belsky

August 13, 2002

R. Kent Weaver

August 1, 2000

Higher Education K-12 Education

Economic Studies

The Hamilton Project

June 20, 2024

Modupe (Mo) Olateju, Grace Cannon, Kelsey Rappe

June 14, 2024

Jon Valant, Nicolas Zerbino

June 13, 2024

- DOI: 10.1086/445813

- Corpus ID: 144855073

Education and Social Mobility

- John P. Neelsen

- Published in Comparative Education Review 1 February 1975

- Education, Sociology

The Benefits of Education and Social Mobility

- Categories: Importance of Education Social Mobility

About this sample

Words: 700 |

Updated: 29 March, 2024

Words: 700 | Pages: 2 | 4 min read

Education and Social Mobility: A Pathway to Advancement

Should follow an “upside down” triangle format, meaning, the writer should start off broad and introduce the text and author or topic being discussed, and then get more specific to the thesis statement.

Provides a foundational overview, outlining the historical context and introducing key information that will be further explored in the essay, setting the stage for the argument to follow.

Cornerstone of the essay, presenting the central argument that will be elaborated upon and supported with evidence and analysis throughout the rest of the paper.

The topic sentence serves as the main point or focus of a paragraph in an essay, summarizing the key idea that will be discussed in that paragraph.

The body of each paragraph builds an argument in support of the topic sentence, citing information from sources as evidence.

After each piece of evidence is provided, the author should explain HOW and WHY the evidence supports the claim.

Should follow a right side up triangle format, meaning, specifics should be mentioned first such as restating the thesis, and then get more broad about the topic at hand. Lastly, leave the reader with something to think about and ponder once they are done reading.

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Verified writer

- Expert in: Education Sociology

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

1 pages / 469 words

5 pages / 2223 words

4 pages / 1694 words

6 pages / 2713 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Social Mobility

The American Dream is a concept deeply ingrained in the fabric of American society. It is the belief that anyone, regardless of their background or circumstances, can achieve success and prosperity through hard work and [...]

The concept of social roles has long been a subject of intrigue and debate in the realm of sociology and psychology. This essay aims to delve into the complex landscape of social roles, evaluating their validity, influence, and [...]

Introduction:In the pursuit of happiness, individuals are often confronted with numerous challenges that test their resilience and determination. The film "The Pursuit of Happyness," directed by Gabriele Muccino, explores the [...]

The Importance Of Academic AchievementAs we embark on our educational journey, we may often wonder about the significance of academic achievement. Why do we spend countless hours studying, attending lectures, and writing essays? [...]

Acemoglu, D., Johnson, S., & Robinson, J. A. (2001). The colonial origins of comparative development: An empirical investigation. American Economic Review, 91(5), 1369-1401.Alesina, A., Devleeschauwer, A., Easterly, W., Kurlat, [...]

Social mobility, a fundamental concept in sociology, refers to the movement of individuals or groups within the social hierarchy, typically divided into social classes. It encompasses the upward or downward transition in [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Social Mobility and Higher Education

- Reference work entry

- First Online: 01 January 2020

- pp 2557–2562

- Cite this reference work entry

- Vikki Boliver 3 &

- Paul Wakeling 4

133 Accesses

1 Citations

Absolute mobility ; Relative mobility ; Social fluidity ; Social openness

The impact of participation in tertiary-level education on the movement of individuals up or down the social class structure from one generation to the next (intergenerational mobility) or during the course of a career (intragenerational mobility).

Social mobility refers to the movement of individuals between different positions in the social structure over time. Closed societies are characterized by ascription, whereby social position is assigned early in life and is difficult to change. Contemporary notions of the good society instead emphasize openness and a shift from ascription to attainment, whereby social position is not determined by inheritance but rather by ability, effort, and disposition. Within sociology, studies of social mobility focus on the association between parental and filial social position across generations, typically employing occupational social class as the key measure.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Institutional subscriptions

Arcidiacono, Peter. 2004. Ability sorting and the returns to college major. Journal of Econometrics 121(1): 343–375.

Google Scholar

Baker, David P. 2011. Forward and backward, horizontal and vertical: Transformation of occupational credentialing in the schooled society. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility 29(1): 5–29.

Bell, Daniel. 1973. The coming of post-industrial society . New York: Basic Books.

Boliver, Vikki. 2011. Expansion, differentiation, and the persistence of social class inequalities in British higher education. Higher Education 61(3): 229–242.

Boliver, Vikki. 2013. How fair is access to more prestigious UK Universities? British Journal of Sociology 64(2): 344–364.

Boudon, Raymond. 1974. Education, opportunity and social inequality . New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Breen, Richard. 2005. Social mobility in Europe . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Breen, Richard. 2010. Educational expansion and social mobility in the 20th century. Social Forces 89(2): 365–388.

Breen, Richard, and Jan O. Jonsson. 2005. Inequality of opportunity in comparative perspective: Recent research on educational attainment and social mobility. Annual Review of Sociology 31: 223–243.

Brint, Steven, and Jerome Karabel. 1989. The diverted dream . New York: Oxford University Press.

Britton, Jack, Lorraine Dearden, Neil Shephard, and Anna Vignoles. 2016. How English domiciled graduate earnings vary with gender, institution attended, subject and socio-economic background , Working Paper W16/06. London: Institute for Fiscal Studies.

Bukodi, Erzsébet, and John Goldthorpe. 2016. Educational attainment – relative or absolute – as a mediator of intergenerational class mobility in Britain. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility 43: 5–15.

Collins, Randall. 1979. The credential society . New York: Academic Press.

Davies, Scott, and Neil Guppy. 1997. Fields of study, college selectivity, and student inequalities in higher education. Social Forces 75: 1417–1438.

Erikson, Robert, and John H. Goldthorpe. 1992. The constant flux: Study of class mobility in industrial societies . Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Goldthorpe, John H., and Michelle Jackson. 2008. Education-based meritocracy: The barriers to its realisation. In Social class: How does it work? ed. Annette Lareau and Dalton Conley, 93–117. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Halsey, A.H. 1993. Trends in access and equity in higher education: Britain in international perspective. Oxford Review of Education 19(2): 129–140.

Hout, Michael. 2006. Maximally maintained inequality and essentially maintained inequality: Crossnational comparisons. Sociological Theory and Methods 21(2): 237–252.

Jackson, Michelle, John H. Goldthorpe, and Colin Mills. 2005. Education, employers and class mobility. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility 23: 3–34.

Jerrim, John, and Lindsey Macmillan. 2015. Income inequality, intergenerational mobility, and the Great Gatsby Curve: Is education the key? Social Forces 94(2): 505–533.

Jerrim, John, and Anna Vignoles. 2015. University access for disadvantaged children: A comparison across countries. Higher Education 70(6): 903–921.

Jerrim, John, Anna K. Chmielewski, and Phil Parker. 2015. Socioeconomic inequality in access to high-status colleges: A cross-country comparison. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility 42: 20–32.

Kerr, Clark, John Dunlop, Frederick Harbison, and Charles Myers. 1960. Industrialism and industrial man . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Lucas, Samuel R. 2001. Effectively maintained inequality: Education transitions, track mobility, and social background effects. American Journal of Sociology 106(6): 1642–1690.

Raftery, Adrian E., and Michael Hout. 1993. Maximally maintained inequality: Expansion, reform, and opportunity in Irish education, 1921–75. Sociology of Education 66: 41–62.

Roksa, Josipa, and Melissa Velez. 2010. When studying schooling is not enough: Incorporating employment in models of educational transitions. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility 28: 5–21.

Schofer, Evan, and John W. Meyer. 2005. The worldwide expansion of higher education in the twentieth century. American Sociological Review 70(6): 898–920.

Shavit, Yossi, and Hans-Peter Blossfeld. 1993. Persistent inequality: Changing educational attainment in thirteen countries . Boulder: Westview Press.

Shavit, Yossi, Richard Arum, and Adam Gamoran (eds.). 2007. Stratification in higher education: A comparative study . Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Spence, Michael. 1973. Job market signalling. Quarterly Journal of Economics 87: 355–374.

Wakeling, Paul, and Mike Savage. 2015. Entry to elite positions and the stratification of higher education in Britain. The Sociological Review 63(2): 290–320.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Applied Social Sciences, Durham University, Durham, UK

Vikki Boliver

Department of Education, University of York, York, UK

Paul Wakeling

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Vikki Boliver .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

CIPES - Centre for Research in Higher Education Policies and Faculty of Economics - U., Porto, Portugal

Pedro Nuno Teixeira

Department of Education, Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea (Republic of)

Jung Cheol Shin

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 Springer Nature B.V.

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Boliver, V., Wakeling, P. (2020). Social Mobility and Higher Education. In: Teixeira, P.N., Shin, J.C. (eds) The International Encyclopedia of Higher Education Systems and Institutions. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-8905-9_43

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-8905-9_43

Published : 19 August 2020

Publisher Name : Springer, Dordrecht

Print ISBN : 978-94-017-8904-2

Online ISBN : 978-94-017-8905-9

eBook Packages : Education Reference Module Humanities and Social Sciences Reference Module Education

Share this entry

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Social History

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Emotions

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music and Media

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Oncology

- Medical Toxicology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Cognitive Psychology

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business Ethics

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic History

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- Ethnic Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Politics and Law

- Politics of Development

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

7 Educational Mobility in the Developing World

- Published: December 2021

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This chapter reviews the small but growing literature on intergenerational educational mobility in the developing world. Education is a critical determinant of economic wellbeing, and it predicts a range of nonpecuniary outcomes such as marriage, fertility, health, crime, and political attitudes. We show that developing nations feature stronger intergenerational educational persistence than high-income countries, in spite of substantial educational expansion in the last decades. We consider variations in mobility across gender and region, and discuss the macro-level correlates of educational mobility in developing countries. The chapter also discusses the literatures on concepts and measurement of educational mobility, theoretical perspectives to understand educational mobility across generations, and the role that education plays in the economic mobility process, and it applies these literatures to understand educational mobility in the developing world.

7.1 Introduction

Educational mobility captures the association between parents’ and adult children’s schooling attainment. Along with measures of occupational and economic mobility, it provides information about equality of opportunity in society. A strong association signals that the chances to attain formal schooling are largely determined by the advantages of birth. A weak association suggests that everyone, regardless of family educational resources, has similar chances to attain high (or low) levels of schooling.

While much mobility research focuses on occupational and economic indicators such as earnings, income, class, or occupational status, schooling is a distinct and important socioeconomic domain. Educational attainment is the main predictor of earnings in contemporary societies, and the earnings returns to schooling are greater in developing than in wealthy countries (Psacharopoulos and Patrinos 2018 ). Educational attainment has intrinsic value, and it predicts a range of nonpecuniary outcomes including health, longevity, fertility, marriage and parenting, crime, political participation, and attitudes, in both the developing and the developed world (Cutler and Lleras-Muney 2008 ; Lochner 2013 ; Omariba 2006 ; Oreopoulos and Salvanes 2011 ).

As well as being a relevant outcome in its own right, educational attainment plays a central role in the process of intergenerational economic and occupational mobility. Education has been found to be the main vehicle both for economic persistence across generations and for intergenerational mobility (Hout and DiPrete 2006 ). Education is the main vehicle for persistence because advantaged parents are able to afford more and better education for their children. Education is at the same time the main vehicle for economic mobility because most of the variance in educational attainment is not tied to social origins.

Studying educational mobility also has practical advantages compared with economic mobility. Most people complete their education by their early adulthood. As a result, measures of educational attainment among adults at a single point in time provide highly valid and stable information about completed schooling. This contrasts with measures of earnings, which can vary widely from year to year. As a result, researchers need to obtain multiple measures over time in order to approach a measure of ‘permanent earnings’ (Friedman 1957 ).

Furthermore, questions about educational attainment are usually not perceived as sensitive by survey respondents, and they have good recall, refusal, and reliability properties. This is particularly advantageous when information about parents’ education is retrospectively reported by adult children, which is the case of most surveys in the developing world.

Because of these practical advantages, intergenerational educational mobility has been measured in many countries of the world, including developing and wealthy nations. An early cross-country assessment of mobility across cohorts born from the 1930s to the 1970s included 42 countries (Hertz et al. 2008 ). A recent update considered 148 nations, with good representation across all continents (World Bank 2018 ).

Researchers have found substantial variation in intergenerational educational mobility across the world, with Northern European countries usually featuring the highest levels of mobility, and Latin American countries until recently featuring the lowest levels. Even if the exact rankings vary somewhat depending on the measure used (more on this later), these country rankings closely resemble rankings based on intergenerational earnings mobility, suggesting a close association between these measures. Both economic and educational mobility are related to economic inequality in cross-sectional comparisons across countries, such that the Great Gatsby Curve applies to both measures. In fact, the few analyses that have explicitly compared measures of educational and economic mobility have found a strong although by no means perfect correlation between the two (Björklund and Jäntti 2011 ; Blanden 2013 ).

Even if basic descriptive analyses of educational mobility are available for a large number of developing countries, the study of educational mobility in the developing world has been limited. First, the study of mechanisms for the intergenerational educational association is largely restricted to wealthy countries. Second, there is only a small literature on the association between mobility and macro-level factors such as economic development and public educational spending, as well as on the impact of economic crises on educational mobility in developing countries. Moreover, this literature is scattered and focused on some countries in the developing world, such as Latin American nations, India, and South Africa.

This review will consider the trends and patterns of educational mobility in the developing world. We will explicitly compare these patterns with the developed world whenever possible, in order to gain analytical insight and to examine the relevance of context. The review is organized as follows. Section 7.2 examines concepts and measures of educational mobility. Section 7.3 examines theoretical approaches to accounting for the mechanisms of intergenerational educational persistence. Section 7.4 reviews patterns and trends of intergenerational educational mobility around the world, with an emphasis on developing regions. The section also examines differences in mobility by gender and macro-level correlates of educational mobility. Finally, Section 7.5 focuses on the relationship between educational and economic mobility, and the role of education in the intergenerational transmission of economic advantage and mentions policy implications of the literature.

7.2 Concepts and measures in the study of intergenerational educational mobility

Educational mobility captures the association between parents’ schooling attainment and their children’s attainment. Two types of mobility provide complementary information. Absolute mobility captures the total observed change in educational attainment across generations. Overall change across generations is driven by both educational upgrades affecting the entire population over time, and the allocation of education based on parents’ education net of overall upgrade. Typical measures of absolute mobility include the proportion of individuals with higher levels of educational attainment than their parents (upward mobility) and those with less attainment than their parents (downward mobility). Relative mobility, in turn, captures the association between parents’ and children’s education net of any change in the distribution of schooling across generations.

The analysis of educational mobility tends to focus on relative mobility. This is understandable given that this measure provides a more direct assessment of equality of opportunity in society. However, educational expansion provides an important impetus for absolute educational mobility as experienced by individuals, particularly in contexts, such as developing countries, where access to formal education has expanded greatly across cohorts. For example, Brazilians born in 1990 attained on average 10 years of schooling. In contrast, their parents attained on average only six years of schooling (Leone 2017 ). This substantial upward mobility might be entirely consistent with no increase in relative mobility if, in a context in which everyone benefits from educational expansion, the allocation of educational gains remains as strongly tied to parents’ education as before.

7.2.1 How is educational mobility measured?