Module 9: Substance-Related and Addictive Disorders

Case studies: substance-abuse disorders, learning objectives.

- Identify substance abuse disorders in case studies

Case Study: Benny

The following story comes from Benny, a 28-year-old living in the Metro Detroit area, USA. Read through the interview as he recounts his experiences dealing with addiction and recovery.

Q : How long have you been in recovery?

Benny : I have been in recovery for nine years. My sobriety date is April 21, 2010.

Q: What can you tell us about the last months/years of your drinking before you gave up?

Benny : To sum it up, it was a living hell. Every day I would wake up and promise myself I would not drink that day and by the evening I was intoxicated once again. I was a hardcore drug user and excessively taking ADHD medication such as Adderall, Vyvance, and Ritalin. I would abuse pills throughout the day and take sedatives at night, whether it was alcohol or a benzodiazepine. During the last month of my drinking, I was detached from reality, friends, and family, but also myself. I was isolated in my dark, cold, dorm room and suffered from extreme paranoia for weeks. I gave up going to school and the only person I was in contact with was my drug dealer.

Q : What was the final straw that led you to get sober?

Benny : I had been to drug rehab before and always relapsed afterwards. There were many situations that I can consider the final straw that led me to sobriety. However, the most notable was on an overcast, chilly October day. I was on an Adderall bender. I didn’t rest or sleep for five days. One morning I took a handful of Adderall in an effort to take the pain of addiction away. I knew it wouldn’t, but I was seeking any sort of relief. The damage this dosage caused to my brain led to a drug-induced psychosis. I was having small hallucinations here and there from the chemicals and a lack of sleep, but this time was different. I was in my own reality and my heart was racing. I had an awful reaction. The hallucinations got so real and my heart rate was beyond thumping. That day I ended up in the psych ward with very little recollection of how I ended up there. I had never been so afraid in my life. I could have died and that was enough for me to want to change.

Q : How was it for you in the early days? What was most difficult?

Benny : I had a different experience than most do in early sobriety. I was stuck in a drug-induced psychosis for the first four months of sobriety. My life was consumed by Alcoholics Anonymous meetings every day and sometimes two a day. I found guidance, friendship, and strength through these meetings. To say early sobriety was fun and easy would be a lie. However, I did learn it was possible to live a life without the use of drugs and alcohol. I also learned how to have fun once again. The most difficult part about early sobriety was dealing with my emotions. Since I started using drugs and alcohol that is what I used to deal with my emotions. If I was happy I used, if I was sad I used, if I was anxious I used, and if I couldn’t handle a situation I used. Now that the drinking and drugs were out of my life, I had to find new ways to cope with my emotions. It was also very hard leaving my old friends in the past.

Q : What reaction did you get from family and friends when you started getting sober?

Benny : My family and close friends were very supportive of me while getting sober. Everyone close to me knew I had a problem and were more than grateful when I started recovery. At first they were very skeptical because of my history of relapsing after treatment. But once they realized I was serious this time around, I received nothing but loving support from everyone close to me. My mother was especially helpful as she stopped enabling my behavior and sought help through Alcoholics Anonymous. I have amazing relationships with everyone close to me in my life today.

Q : Have you ever experienced a relapse?

Benny : I experienced many relapses before actually surrendering. I was constantly in trouble as a teenager and tried quitting many times on my own. This always resulted in me going back to the drugs or alcohol. My first experience with trying to become sober, I was 15 years old. I failed and did not get sober until I was 19. Each time I relapsed my addiction got worse and worse. Each time I gave away my sobriety, the alcohol refunded my misery.

Q : How long did it take for things to start to calm down for you emotionally and physically?

Benny : Getting over the physical pain was less of a challenge. It only lasted a few weeks. The emotional pain took a long time to heal from. It wasn’t until at least six months into my sobriety that my emotions calmed down. I was so used to being numb all the time that when I was confronted by my emotions, I often freaked out and didn’t know how to handle it. However, after working through the 12 steps of AA, I quickly learned how to deal with my emotions without the aid of drugs or alcohol.

Q : How hard was it getting used to socializing sober?

Benny : It was very hard in the beginning. I had very low self-esteem and had an extremely hard time looking anyone in the eyes. But after practice, building up my self-esteem and going to AA meetings, I quickly learned how to socialize. I have always been a social person, so after building some confidence I had no issue at all. I went back to school right after I left drug rehab and got a degree in communications. Upon taking many communication classes, I became very comfortable socializing in any situation.

Q : Was there anything surprising that you learned about yourself when you stopped drinking?

Benny : There are surprises all the time. At first it was simple things, such as the ability to make people smile. Simple gifts in life such as cracking a joke to make someone laugh when they are having a bad day. I was surprised at the fact that people actually liked me when I wasn’t intoxicated. I used to think people only liked being around me because I was the life of the party or someone they could go to and score drugs from. But after gaining experience in sobriety, I learned that people actually enjoyed my company and I wasn’t the “prick” I thought I was. The most surprising thing I learned about myself is that I can do anything as long as I am sober and I have sufficient reason to do it.

Q : How did your life change?

Benny : I could write a book to fully answer this question. My life is 100 times different than it was nine years ago. I went from being a lonely drug addict with virtually no goals, no aspirations, no friends, and no family to a productive member of society. When I was using drugs, I honestly didn’t think I would make it past the age of 21. Now, I am 28, working a dream job sharing my experience to inspire others, and constantly growing. Nine years ago I was a hopeless, miserable human being. Now, I consider myself an inspiration to others who are struggling with addiction.

Q : What are the main benefits that emerged for you from getting sober?

Benny : There are so many benefits of being sober. The most important one is the fact that no matter what happens, I am experiencing everything with a clear mind. I live every day to the fullest and understand that every day I am sober is a miracle. The benefits of sobriety are endless. People respect me today and can count on me today. I grew up in sobriety and learned a level of maturity that I would have never experienced while using. I don’t have to rely on anyone or anything to make me happy. One of the greatest benefits from sobriety is that I no longer live in fear.

Case Study: Lorrie

Figure 1. Lorrie.

Lorrie Wiley grew up in a neighborhood on the west side of Baltimore, surrounded by family and friends struggling with drug issues. She started using marijuana and “popping pills” at the age of 13, and within the following decade, someone introduced her to cocaine and heroin. She lived with family and occasional boyfriends, and as she puts it, “I had no real home or belongings of my own.”

Before the age of 30, she was trying to survive as a heroin addict. She roamed from job to job, using whatever money she made to buy drugs. She occasionally tried support groups, but they did not work for her. By the time she was in her mid-forties, she was severely depressed and felt trapped and hopeless. “I was really tired.” About that time, she fell in love with a man who also struggled with drugs.

They both knew they needed help, but weren’t sure what to do. Her boyfriend was a military veteran so he courageously sought help with the VA. It was a stroke of luck that then connected Lorrie to friends who showed her an ad in the city paper, highlighting a research study at the National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA), part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH.) Lorrie made the call, visited the treatment intake center adjacent to the Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, and qualified for the study.

“On the first day, they gave me some medication. I went home and did what addicts do—I tried to find a bag of heroin. I took it, but felt no effect.” The medication had stopped her from feeling it. “I thought—well that was a waste of money.” Lorrie says she has never taken another drug since. Drug treatment, of course is not quite that simple, but for Lorrie, the medication helped her resist drugs during a nine-month treatment cycle that included weekly counseling as well as small cash incentives for clean urine samples.

To help with heroin cravings, every day Lorrie was given the medication buprenorphine in addition to a new drug. The experimental part of the study was to test if a medication called clonidine, sometimes prescribed to help withdrawal symptoms, would also help prevent stress-induced relapse. Half of the patients received daily buprenorphine plus daily clonidine, and half received daily buprenorphine plus a daily placebo. To this day, Lorrie does not know which one she received, but she is deeply grateful that her involvement in the study worked for her.

The study results? Clonidine worked as the NIDA investigators had hoped.

“Before I was clean, I was so uncertain of myself and I was always depressed about things. Now I am confident in life, I speak my opinion, and I am productive. I cry tears of joy, not tears of sadness,” she says. Lorrie is now eight years drug free. And her boyfriend? His treatment at the VA was also effective, and they are now married. “I now feel joy at little things, like spending time with my husband or my niece, or I look around and see that I have my own apartment, my own car, even my own pots and pans. Sounds silly, but I never thought that would be possible. I feel so happy and so blessed, thanks to the wonderful research team at NIDA.”

- Liquor store. Authored by : Fletcher6. Located at : https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_Bunghole_Liquor_Store.jpg . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Benny Story. Provided by : Living Sober. Located at : https://livingsober.org.nz/sober-story-benny/ . License : CC BY: Attribution

- One patientu2019s story: NIDA clinical trials bring a new life to a woman struggling with opioid addiction. Provided by : NIH. Located at : https://www.drugabuse.gov/drug-topics/treatment/one-patients-story-nida-clinical-trials-bring-new-life-to-woman-struggling-opioid-addiction . License : Public Domain: No Known Copyright

Masks Strongly Recommended but Not Required in Maryland

Respiratory viruses continue to circulate in Maryland, so masking remains strongly recommended when you visit Johns Hopkins Medicine clinical locations in Maryland. To protect your loved one, please do not visit if you are sick or have a COVID-19 positive test result. Get more resources on masking and COVID-19 precautions .

- Vaccines

- Masking Guidelines

- Visitor Guidelines

News & Publications

New research and insights into substance use disorder.

Addictions to alcohol, illicit drugs and other substances remain a serious threat: According to the National Center for Health Statistics, part of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, from April 2020 to April 2021, nearly 92,000 people in the U.S. fatally overdosed on drugs — the single highest reported death toll during a 12-month period. The National Center for Drug Abuse Statistics has deemed the situation “a public health emergency.” All groups ages 15 and older experienced a rise in these grim statistics, intensified by the use of fentanyl.

Currently, substance use disorder affects more than 20 million Americans ages 12 and over. These numbers are troubling, says Johns Hopkins neuroscientist and addiction researcher Andrew Huhn , “but with a multifaceted approach, people with substance use disorders can recover.”

Drawing from his background in neuroscience and behavioral pharmacology, Huhn identifies risk factors for relapse and medication strategies — bolstered by supervised withdrawal and counseling — to improve treatment outcomes. “My research focuses on understanding the human experience of substance use disorder,” he says, noting that medications for opioid overdose, withdrawal and addiction “are safe, effective and continue to save lives.”

Now, thanks to a recent collaboration with Ashley Addiction Treatment, a residential treatment center in Havre de Grace, Maryland, Huhn, Kelly Dunn and colleagues are combining efforts to identify patients likely to benefit from supervised withdrawal or opioid maintenance therapy. The goal is to expand treatment options to improve health care for people with the condition. “Relapse remains common, but a subset of patients have done well,” says Dunn.

Concurrently, Huhn, Dunn and colleagues are building a research database based on the Trac9 program, which charts patients’ progress in real-time through technology, such as a tablet or phone — as well as alerting clinicians to a relapse and the need for intervention. They are also using wearable devices to monitor sleep and cardiovascular outcomes, and a smart phone application to track each time a patient notes having successfully ignored a craving for alcohol or a drug. Much of this research takes place at Behavioral Pharmacology Research Unit , located on the Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center campus.

Their published work includes studies showing a greater need for treatment of older adults with alcohol and opioid use disorders. Two additional studies have garnered national attention, both on how fentanyl use affects the treatment of opioid use disorder . Much of the illicit opioid supply in the U.S. is mixed with fentanyl, leading to a recent surge in fentanyl-related overdose deaths.

Yet another study showed promise in the use of a sleep medication to improve opioid withdrawal outcomes. Researchers in Huhn’s lab continue to glean insights from neuroimaging, ambulatory monitoring in real time, and repeated measures of behaviors.

Greg Hobelmann , the CEO of Ashley, who trained at Johns Hopkins and is a part-time faculty member, chairs an elective at the Ashley facility in addictions psychiatry. He, along with Eric Strain and Huhn are building infrastructure that includes intake data on every patient, as well as outcomes data when people complete the Ashley program — and for the year that follows. Biospecimens will also be included in the project, for studies in areas such as genetics.

“The biggest and most exciting thing is being able to create predictive models of relapse risk and then create strategies to improve those outcomes,” says Huhn. Jimmy Potash , director of the Johns Hopkins Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences couldn’t agree more. “This will be a powerful platform for discovery of better approaches to treating addiction,” he says. “I’m eager to see it — and our relationship with Ashley Addiction — move forward.”

Despite enduring challenges in addictions psychiatry, Huhn is hopeful. “We have the ability to continue collecting data and to test hypotheses,” he says. “It’s the kind of stuff we hope will turn into a game-changer, similar to what has happened in cancer and heart disease treatments. We build research into the treatment and let that guide our approach to care.”

Learn about a web-based education intervention to reduce opioid overdose, Low-Cost Intervention Reduces Risk of Opioid Overdose.

Related Reading

Johns hopkins bayview’s center for addiction and pregnancy supports new mothers and their babies in the fight against substance use disorders.

Center offers judgment-free care, helping moms and newborns

- Liberty University

- Jerry Falwell Library

- Special Collections

- < Previous

Home > ETD > Doctoral > 6036

Doctoral Dissertations and Projects

Success treating substance use disorder: a case study of minnesota adult and teen challenge.

John Joseph Lenss , Liberty University Follow

Rawlings School of Divinity

Doctor of Philosophy

Rich Sironen

Substance use disorder, addiction recovery, treatment, long-term recovery, dropout, success rate

Disciplines

Leadership Studies | Social and Behavioral Sciences

Recommended Citation

Lenss, John Joseph, "Success Treating Substance Use Disorder: A Case Study of Minnesota Adult and Teen Challenge" (2024). Doctoral Dissertations and Projects . 6036. https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/doctoral/6036

Minnesota Adult and Teen Challenge (MNTC) is an addiction treatment center. The reason for this qualitative case study was to discover why clients of substance use disorder treatment programs believe that they can graduate from their program when 50% of those who start the same long-term program drop out. This case study focused on graduates from MNTC in Minneapolis, Minnesota. This study discovered the graduates' common attributes that may improve MNTC treatment center programs, which could decrease the number of people who walk away from addiction recovery programs prematurely and increase the number of those who graduate. According to MNTC records and the literature, 50% of clients in long-term recovery programs at MNTC drop out and must start over in the program before they graduate. This case study documented graduates' opinions on why they successfully completed the long-term program for the Minneapolis, Minnesota Adult and Teen Challenge (MNTC). The definition of an MNTC graduate was graduating from the program and not having a relapse for one year. The theory guiding this study was Ajzen’s theory of planned behavior, which proposes that an individual's decision whether to engage in any specific behavior, such as drug or alcohol use, is predicated by their intention to engage in that behavior. Likewise, Ajzen’s theory can explain a person’s intention to stop substance use as a conscious behavior, which this study collected information to understand. The academic community—mainly those interested in addiction treatment and recovery programs—played a crucial role in this research, as their expertise and insights significantly contributed to understanding and improving addiction recovery programs.

Since September 19, 2024

Included in

Leadership Studies Commons

- Collections

- Faculty Expert Gallery

- Theses and Dissertations

- Conferences and Events

- Open Educational Resources (OER)

- Explore Disciplines

Advanced Search

- Notify me via email or RSS .

Faculty Authors

- Submit Research

- Expert Gallery Login

Student Authors

- Undergraduate Submissions

- Graduate Submissions

- Honors Submissions

Home | About | FAQ | My Account | Accessibility Statement

Privacy Copyright

Substance Use Disorders and Addiction: Mechanisms, Trends, and Treatment Implications

Information & authors, metrics & citations, view options, insights into mechanisms related to cocaine addiction using a novel imaging method for dopamine neurons, treatment implications of understanding brain function during early abstinence in patients with alcohol use disorder, relatively low amounts of alcohol intake during pregnancy are associated with subtle neurodevelopmental effects in preadolescent offspring, increased comorbidity between substance use and psychiatric disorders in sexual identity minorities, trends in nicotine use and dependence from 2001–2002 to 2012–2013, conclusions, information, published in.

- Substance-Related and Addictive Disorders

- Addiction Psychiatry

- Transgender (LGBT) Issues

Competing Interests

Export citations.

If you have the appropriate software installed, you can download article citation data to the citation manager of your choice. Simply select your manager software from the list below and click Download. For more information or tips please see 'Downloading to a citation manager' in the Help menu .

| Format | |

|---|---|

| Citation style | |

| Style | |

View options

Login options.

Already a subscriber? Access your subscription through your login credentials or your institution for full access to this article.

Not a subscriber?

Subscribe Now / Learn More

PsychiatryOnline subscription options offer access to the DSM-5-TR ® library, books, journals, CME, and patient resources. This all-in-one virtual library provides psychiatrists and mental health professionals with key resources for diagnosis, treatment, research, and professional development.

Need more help? PsychiatryOnline Customer Service may be reached by emailing [email protected] or by calling 800-368-5777 (in the U.S.) or 703-907-7322 (outside the U.S.).

Share article link

Copying failed.

NEXT ARTICLE

Request username.

Can't sign in? Forgot your username? Enter your email address below and we will send you your username

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to retrieve your username

Create a new account

Change password, password changed successfully.

Your password has been changed

Reset password

Can't sign in? Forgot your password?

Enter your email address below and we will send you the reset instructions

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to reset your password.

Your Phone has been verified

As described within the American Psychiatric Association (APA)'s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use , this website utilizes cookies, including for the purpose of offering an optimal online experience and services tailored to your preferences. Please read the entire Privacy Policy and Terms of Use. By closing this message, browsing this website, continuing the navigation, or otherwise continuing to use the APA's websites, you confirm that you understand and accept the terms of the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, including the utilization of cookies.

An official website of the United States government

Here’s how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

Header - Callout

In Crisis? Call or Text 988

Substance use, mental health challenges widespread in 2021

Data sources used.

- National Survey on Drug Use and Health 2021

- Open Access

- By Publication (A-Z)

- Case Reports

- Publication Ethics

- Publishing Policies

- Editorial Policies

- Submit Manuscript

- About Graphy

New to Graphy Publications? Create an account to get started today.

Registered Users

Have an account? Sign in now.

- Full-Text HTML

- Full-Text PDF

- About This Journal

- Aims & Scope

- Editorial Board

- Editorial Process

- Author Guidelines

- Special Issues

- Articles in Press

Jo-Hanna Ivers 1* and Kevin Ducray 2

In October 2012, 83 front-line Irish service providers working in the addiction treatment field received accreditation as trained practitioners in the delivery of a number of evidence-based positive reinforcement approaches that address substance use: 52 received accreditation in the Community Reinforcement Approach (CRA), 19 in the Adolescent Community Reinforcement Approach (ACRA) and 12 in Community Reinforcement and Family Training (CRAFT). This case study presents the treatment of a 17-year-old white male engaging in high-risk substance use. He presented for treatment as part of a court order. Treatment of the substance use involved 20 treatment sessions and was conducted per Adolescent Community Reinforcement Approach (A-CRA). This was a pilot of A-CRA a promising treatment approach adapted from the United States that had never been tried in an Irish context. A post-treatment assessment at 12-week follow-up revealed significant improvements. At both assessment and following treatment, clinician severity ratings on the Maudsley Addiction Profile (MAP) and the Alcohol Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST) found decreased score for substance use was the most clinically relevant and suggests that he had made significant changes. Also his MAP scores for parental conflict and drug dealing suggest that he had made significant changes in the relevant domains of personal and social functioning as well as in diminished engagement in criminal behaviour. Results from this case study were quite promising and suggested that A-CRA was culturally sensitive and applicable in an Irish context.

1. Theoretical and Research Basis for Treatment

Substance use disorders (SUDs) are distinct conditions characterized by recurrent maladaptive use of psychoactive substances associated with significant distress. These disorders are highly common with lifetime rates of substance use or dependence estimated at over 30% for alcohol and over 10% for other substances [1 , 2] . Changing substance use patterns and evolving psychosocial and pharmacologic treatments modalities have necessitated the need to substantiate both the efficacy and cost effectiveness of these interventions.

Evidence for the clinical application of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) for substance use disorders has grown significantly [3 - 8] . Moreover, CBT for substance use disorders has demonstrated efficacy both as a monotherapy and as part of combination treatment [7] . CBT is a time-limited, problem-focused, intervention that seeks to reduce emotional distress through the modification of maladaptive beliefs, assumptions, attitudes, and behaviours [9] . The underlying assumption of CBT is that learning processes play an imperative function in the development and maintenance of substance misuse. These same learning processes can be used to help patients modify and reduce their drug use [3] .

Drug misuse is viewed by CBT practitioners as learned behaviours acquired through experience [10] . If an individual uses alcohol or a substance to elicit (positively or negatively reinforced) desired states (e.g. euphorigenic, soothing, calming, tension reducing) on a recurrent basis, it may become the preferred way of achieving those effects, particularly in the absence of alternative ways of attaining those desired results. A primary task of treatment for problem substance users is to (1) identify the specific needs that alcohol and substances are being used to meet and (2) develop and reinforce skills that provide alternative ways of meeting those needs [10 , 11] .

CRA is a broad-spectrum cognitive behavioural programme for treating substance use and related problems by identifying the specific needs that alcohol and or other substances are satisfying or meeting. The goal is then to develop and reinforce skills that provide alternative ways of meeting those needs. Consistent with traditional CBT, CRA through exploration, allows the patient to identify negative thoughts, behaviours and beliefs that maintain addiction. By getting the patient to identify, positive non-drug using behaviours, interests, and activities, CRA attempts to provide alternatives to drug use. As therapy progresses the objective is to prevent relapse, increase wellness, and develop skills to promote and sustain well-being. The ultimate aim of CRA, as with CBT is to assist the patient to master a specific set of skills necessary to achieve their goals. Treatment is not complete until those skills are mastered and a reasonable degree of progress has been made toward attaining identified therapy goals. CRA sessions are highly collaborative, requiring the patient to engage in ‘between session tasks’ or homework designed reinforce learning, improve coping skills and enhance self efficacy in relevant domains.

The use of the Community Reinforcement Approach is empirically supported with inpatients [12 , 13] , outpatients [14 - 16] and homeless populations (Smith et al., 1998). In addition, three recent metaanalytic reviews cited CRA as one of the most cost-effective treatment programmes currently available [17 , 18] .

A-CRA is a evidenced based behavioural intervention that is an adapted version of the adult CRA programme [19] . Garner et al [19] modified several of the CRA procedures and accompanying treatment resources to make them more developmentally appropriate for adolescents. The main distinguishing aspect of A-CRA is that it involves caregivers—namely parents or guardians who are ultimately responsible for the adolescent and with whom the adolescent is living.

A-CRA has been tested and found effective in the context of outpatient continuing care following residential treatment [20 - 22] and without the caregiver components as an intervention for drug using, homeless adolescents [23] . More recently, Garner et al [19] collected data from 399 adolescents who participated in one of four randomly controlled trials of the A-CRA intervention, the purpose of which was to examine the extent to which exposure to A-CRA procedures mediated the relationship between treatment retention and outcomes. The authors found adolescents who were exposed to 12 or more A-CRA procedures were significantly more likely to be in recovery at follow-up.

Combining A-CRA with relapse prevention strategies receives strong support as an evidence based, best practice model and is widely employed in addiction treatment programmes. Providing a CBT-ACRA therapeutic approach is imperative as it develops alternative ways of meeting needs and thus altering dependence.

2. Case Introduction

Alan is a 17 year-old male currently living in County Dublin. Alan presented to the agency involuntarily and as a requisite of his Juvenile Liaison Officer who was seeing him on foot of prior drugs arrest for ‘possession with intent to supply’; a more serious charge than a simple ‘drugs possession’ charge. As Alan had no previous charges he was placed on probation for one year. This was Alan’s first contact with the treatment services. A diagnostic assessment was completed upon entry to treatment and included completion of a battery of instruments comprising the Maudsley Addiction Profile (MAP), The World Health Organization Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST) and the Beck Youth Inventory (BYI) (see appendices for full description of outcome measures) (Table 1).

3. Diagnostic Criteria

The apparent symptoms of substance dependency were: (1) Loss of Control - Alan had made several attempts at controlling the amounts of cannabis he consumed, but those times when he was able to abstain from cannabis use were when he substituted alcohol and/or other drugs. (2) Family History of Alcohol/Drug Usage - Alan’s eldest sister who is now 23 years old is in recovery from opiate abuse. She was a chronic heroin user during her early adult years [17 - 21] . During this period, which corresponds to Alan’s early adolescent years [12 - 15] she lived in the family home (3) Changes in Tolerance - Alan began per day. At presentation he was smoking six to eight cannabis joints daily through the week, and eight to twelve joints daily on weekends.

4. Psychosocial, Medical and Family History

At time of intake Alan was living with both of his parents and a sister, two years his senior, in the family home. Alan was the youngest and the only boy in his family. He had two other older sisters, 5 and 7 years his senior. He was enrolled in his 5th year of secondary school but at the time of assessment was expelled from all classes. Alan had superior sporting abilities. He played for the junior team of a first division football team and had the prospect of a professional career in football. He reported a family history positive for substance use disorders. An older sister was in recovery for opiate dependence. Apart from his substance use Alan reported no significant psychological difficulties or medical problems. His motives for substance use were cited as boredom, curiosity, peer pressure, and pleasure seeking. His triggers for use were relationship difficulties at home, boredom and peer pressure. Pre-morbid personality traits included thrill seeking and impulsivity (Table 2).

5. Case Conceptualisation

A CBT case formulation is based on the cognitive model, which hypothesizes that "a person’s feelings and emotions are influenced by their perception of events" . It is not the actual event that determines how the person feels, but rather how they construe the event (Beck, 1995 p14). Moreover, cognitive theory posits that the “child learns to construe reality through his or her early experiences with the environment, especially with significant others” and that “sometimes these early experiences lead children to accept attitudes and beliefs that will later prove maladaptive” [24] . A CBT formulation (or case conceptualisation) is one of the key underpinnings of Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT). It is the ‘blueprint’ which aids the therapist to understand and explain the patient’s’ problems.

Formulation driven CBT enables the therapist to develop an individualised understanding of the patient and can help to predict the difficulties that a patient may encounter during therapy. In Alan’s case, exploring his existing negative automatic thoughts about regarding school and his academic competences highlighted the difficulties he could experience with CBT homework completion. Whilst Alan was good at between session therapy assignments, an exploration of what is meant by ‘homework’ in a CBT context was crucial.

A collaborative CBT formulation was done diagrammatically together with Alan (Figure 1). This formulation aimed to describe his presenting problems and using CBT theory, to explore explanatory inferences about the initiating and maintaining factors of his drug use which could practically inform meaningful interventions.

Simmons and Griffiths et al. make the insightful observation that particular group differences need to be specifically considered and suggest that the therapist should be cognizant of the role of both society and culture when developing a formulation. They firstly suggest that the impact played by gender, sexuality and socio-cultural roles in the genesis of a psychological disorder, namely the contribution that being a member of a group may have on predisposing and precipitating factors, be carefully considered. An example they offer is the role of poverty on the development of psychological problems, such as the link evidenced between socio economic group and onset of schizophrenia. This was clearly evident in the case of Alan, who being a member of a deprived socioeconomic group, growing up and living in an area with a high level of economic deprivation, perceived that his choices for success were limited. His thinking, as an adolescent boy, was dichotomous in that he saw himself as having only two fixed and limited choices (a) being good at sport he either pursue a career as a professional sportsman or alternatively (b) he engage in crime and work his way up through the ranks as a ‘career criminal’. Simmons & Griffiths secondly suggest that being a member of a particular group can heavily influence a person’s understanding of the causality of their psychological disorder. A third consideration when developing a formulation is the degree to which being a member of a particular group may influence the acceptance or rejection of a member experiencing a psychological illness. Again this is pertinent in Alan’s case as he was part of a sub-group, a gang engaged in crime. For this cohort, crime and drug use were synonymous. Using drugs was viewed as a rite of passage for Alan.

Drug use, according to CBT models, are socially learned behaviours initiated, maintained and altered through the dynamic interaction of triggers, cues, reinforcers, cognitions and environmental factors. The application of a such a formulation, sensitive to Simmons and Griffiths (2009) aforementioned observations, proved useful in affording insights into the contextual and maintaining factors of Alan’s drug use which was heavily influenced by the availability of drugs ,his peer group (with whom he spent long periods of time) and their petty drug dealing and criminality. Similarly, engaging with his football team mates during the lead up to an important match significantly reduced his drug use and at certain times of the year even lead to abstinence. Sharing this formulation allowed him to note how his drug use patterns were driven, as per the CBT paradigm, by modifiable external, transient, and specific factors (e.g. cues, reinforcements, social networks and related expectations and social pressures).

Employing the A-CRA model allowed for this tailored fit as A-CRA specifically encourages the patient to identify their own need and desire for change. Alan identified the specific needs that were met by using substances and he developed and reinforced skills that provided him with alternative ways of meeting those needs. This model worked extremely well for Alan as he had identified and had ready access to a pro- social ‘alternative group’ or community. As he had had access to an alternative positive peer group and another activity (sport) which he was ‘really good at’, he simply needed to see the evidence of how his context could radically affect his substance use; more specifically how his beliefs, thinking and actions in certain circumstances produced very different drug use consequences and outcomes.

6. Course of Treatment and Assessment of Progress

One focus of CBT treatment is on teaching and practising specific helpful behaviours, whilst trying to limit cognitive demands on clients. Repetition is central to the learning process in order to develop proficiency and to ensure that newly acquired behaviours will be available when needed. Therefore, behavioural using rehearsal will emphasize varied, realistic case examples to enhance generalization to real life settings. During practice periods and exercises, patients are asked to identify signals that indicate high-risk situations, demonstrating their understanding of when to use newly acquired coping skills. CBT is designed to remedy possible deficits in coping skills by better managing those identified antecedents to substance use. Individuals who rely primarily on substances to cope have little choice but to resort to substance use when the need to cope arises. Understanding, anticipating and avoiding high risk drug use scenarios or the “early warning signals” of imminent drug use is a key CBT clinical activity.

A major goal of a CBT/A-CRA therapeutic approach is to provide a range of basic alternative skills to cope with situations that might otherwise lead to substance use. As ‘skill deficits’ are viewed as fundamental to the drug use trajectory or relapse process, an emphasis is placed on the development and practice of coping skills. A-CRA was manualised in 2001 as part of the Cannabis Youth Treatment Series (CYT) and was tested in that study [21] and more recently with homeless youth [23] . It was also adapted for use in a manual for Assertive Continuing Care following residential treatment [20] .

There are twelve standard and three optional procedures proposed in the A-CRA model. The delivery of the intervention is flexible and based on individual adolescent needs, though the manual provides some general guidelines regarding the general order of procedures. Optional procedures are ‘Dealing with Failure to Attend’, ‘Job-Seeking Skills’, and ‘Anger Management’. Standard procedures are included in table 3 below. For a more detailed description of sessions and procedures please see appendices.

Smith and Myers describe the theoretical underpinnings of CRA as a comprehensive behavioural program for treating substance-abuse problems. It is based on the belief that environmental contingencies can play a powerful role in encouraging or discouraging drinking or drug use. Consequently, it utilizes social, recreational, familial, and vocational reinforcers to assist consumers in the recovery process. Its goal is to essentially make a sober lifestyle more rewarding than the use of substances. Interestingly the authors note: ‘Oddly enough, however, while virtually every review of alcohol and drug treatment outcome research lists CRA among approaches with the strongest scientific evidence of efficacy, very few clinicians who treat consumers with addictions are familiar with it’. ‘The overall philosophy is to promote community based rewarding of non drug-using behaviour so that the patient makes healthy lifestyle changes’ p.3 [25] .

A-CRA procedures use ‘operant techniques and skills training activities’ to educate patients and present alternative ways of dealing with challenges without substances. Traditionally, CRA is provided in an individual, context-specific approach that focuses on the interaction between individuals and those in their environments. A-CRA therapists teach adolescents when and where to use the techniques, given the reality of each individual’s social environment. This tailored approach is facilitated by conducting a ‘functional analysis’ of the adolescent’s behaviour at the beginning of therapy so they can better understand and interrupt the links in the behavioural chain typically leading to episodes of drug use. A-CRA therapists then teach individuals how to improve communication and other skills, build on their reinforcers for abstinence and use existing community resources that will support positive change and constructive support systems.

A-CRA emphasises lapse and relapse prevention. Relapseprevention cognitive behavioural therapy (RP-CBT) is derived from a cognitive model of drug misuse. The emphasis is on identifying and modifying irrational thoughts, managing negative mood and intervening after a lapse to prevent a full-blown relapse [26] . The emphasis is on development of skills to (a) recognize High Risk Situations (HRS) or states where clients are most vulnerable to drug use, (b) avoidance of HRS, and (C) to use a variety of cognitive and behavioural strategies to cope effectively with these situations. RPCBT differs from typical CBT in that the accent is on training people who misuse drugs to develop skills to identify and anticipate situations or states where they are most vulnerable to drug use and to use a range of cognitive and behavioural strategies to cope effectively with these situations [26] .

7. Access and Barriers to Care

Alan engaged with the service for eight months. During this time he received twenty sessions, three of which were assessment focused, the remaining seventeen sessions were A-CRA focused; two of the seventeen involved his mother, the remaining fifteen were individual. As Alan was referred by the probation services, he was initially somewhat ambivalent about drug use focussed interventions. His early motivation for engagement was primarily to avoid the possibility of a custodial sentence.

8. Treatment

My sessions with Alan were guided by the principles of A-CRA [27] which focuses on coping skills training and relapse prevention approaches to the treatment of addictive disorders. Prior to engaging with Alan, I had completed the training course and commenced the A-CRA accreditation process, both under the stewardship of Dr Bob Meyers, whose training and publication offers detailed guidelines on skills training and relapse prevention with young people in a similar context [27] .

During the early part of each session I focused on getting a clear understanding of Alan’s current concerns, his general level of functioning, his substance abuse and pattern of craving during the past week. His experiences with therapy homework, the primary focus being on what insight he gained by completing such exercises was also explored. I spent considerable time engaged in a detailed review of Alan’s experience with the implementation of homework tasks during which the following themes were reviewed:

-Gauging whether drug use cessation was easier or harder than he anticipated? -Which, if any, of the coping strategies worked best? -Which strategies did not work as well as expected. Did he develop any new strategies? -Conveying the importance of skills practice, emphasising how we both gained greater insights into how cognitions influenced his behaviour. After developing a clear sense of Alan’s general functioning, current concerns and progress with homework implementation, I initiated the session topic for that week. I linked the relevance of the session topic to Alan’s current cannabis-related concerns and introduced the topic by using concrete examples from Alan’s recent experience. While reviewing the material, I repeatedly ensured that Alan understood the topic by asking for concrete examples, while also eliciting Alan’s views on how he might use these particular skills in the future.

Godley & Meyers [21] propose a homework exercise to accompany each session. An advantage of using these homework sheets is that they also summarise key points about each topic and therefore serve as a useful reminder to the patient of the material discussed each week. Meyers, et al. (2011) suggests that rather than being bound by the suggested exercises in the manualised approach, they may be used as a starting point for discussing the best way to implement the required skill and to develop individualised variations for new assignments [27] . The final part of each session focused on Alan’s plan for the week ahead and any anticipated high-risk situations. I endeavoured to model the idea that patients can literally ‘plan themselves out of using’ cannabis or other drugs. For each anticipated high-risk situation, we identified appropriate and viable coping skills. Better understanding, anticipating and planning for high-risk situations was difficult in the beginning of treatment as Alan was not particularly used to planning or thinking through his activities. For a patient like Alan, whose home life is often chaotic, this helped promote a growing sense of self efficacy. Similarly, as Alan had been heavily involved with drug use for a long time, he discovered through this process that he had few meaningful activities to fill his time or serve as alternatives to drug use. This provided me with an opportunity to discuss strategies to rebuild an activity schedule and a social network.

During our sessions, several skill topics were covered. I carefully selected skills to match Alan’s needs. I selected coping skills that he has used in the past and introduced one or two more that were consistent with his cognitive style. Alan’s cognitive score indicated a cognitive approach reflecting poor problem solving or planning. Sessions focused on generic skills including interpersonal skills, goal setting, coping with criticism or anger, problem solving and planning. The goal was to teach Alan how to build on his pro- social reinforcers, how to use existing community resources supportive of positive change and how to develop a positive support system.

The sequence in which these topics were presented was based on (a) patient needs and (b) clinician judgment (a full description of individual sessions may be found in appendices).

A-CRA procedures use ‘operant techniques and skills training activities’ to educate patients and present alternative ways of dealing with challenges without substances. Traditionally, CRA is provided in an individual, context-specific approach that focuses on the interaction between individuals and those in their environments. A-CRA therapists teach adolescents when and where to use the techniques, given the reality of each individual’s social environment.

9. Assessment of Treatment Outcome

A baseline diagnostic assessment of outcomes was completed upon treatment entry. This assessment consisted of a battery of psychological instruments including (see appendices for full a description of assessment measures):

-The Maudsley Addiction Profile (MAP). -The Beck Youth Inventories. -The World Health Organization Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST).

In addition to the above, objective feedback on Alan’s clinical and drug use status through urine toxicology screens was an important part of his drug treatment. Urine specimens were collected before each session and available for the following session. The use of toxicology reports throughout treatment are considered a valuable clinical tool. This part of the session presents a good opportunity to review the results of the most recent urine toxicology screen and promote meaningful therapeutic activities in the context of the patient’s treatment goals [28] .

In reporting on substance use since the last session, patients are likely to reveal a great deal about their general level of functioning and the types of issues and problems of most current concern. This allows the clinician to gauge if the patient has made progress in reducing drug use, his current level of motivation, whether there is a reasonable level of support available in efforts to remain abstinent and what is currently bothering him. Functional analyses are opportunistically used throughout treatment as needed. For example, if cannabis use occurs, patients are encouraged to analyse antecedent events so as to determine how to avoid using in similar situations in the future. The purpose is to help the patient understand the trajectory and modifiable contextual factors associated with drug use, challenge unhelpful positive drug use expectancies, identify possible skills deficiencies as well as seeking functionally equivalent non- drug using behaviours so as to reduce the probability of future drug use. The approach I used is based on the work of [28] .

The Functional Analysis was used to identify a number of factors occurring within a relatively brief time frame that influenced the occurrence of problem behaviours. It was used as an initial screening tool as part of a comprehensive functional assessment or analysis of problem behaviour. The results of the functional analysis then served as a basis for conducting direct observations in a number of different contexts to attest to likely behavioural functions, clarify ambiguous functions, and identify other relevant factors that are maintaining the behaviour.

The Happiness Scale rates the adolescent’s feelings about several critical areas of life. It helps therapists and adolescents identify areas of life that adolescents feel happy about and alternatively areas in which they have problems or challenges. Most importantly it identifies potential treatment goals subjectively meaningful to the patient, facilitates positive behaviour change in a range of life domains as well as help clients track their progress during treatment.

Alan’s BYI score (Table 4) indicates that at the time of assessment he was within the average scoring range on ‘self-concept’, and moderately elevated in the areas of ‘depression’, ‘anxiety’, and ‘disruptive behaviour’. His score for ‘anger’ suggested that his anger fell within the extremely elevated range. When this was discussed with Alan he agreed that this was quite accurate. Anger, and in particular controlling his anger, was subjectively identified as a treatment goal.

10. Follow-up

Given that follow-up occurred by telephone it was not feasible to administer the full battery of tests. With Alan’s treatment goals in mind it was decided to administer the MAP and ASSIST. Table 5 below illustrates Alan’s score at baseline and follow-up for the MAP and ASSIST. For summary purposes I have taken areas for concern at baseline for both instruments.

Alan’s score for cannabis was the most clinically relevant as it placed him in the 'high risk’ domain while his alcohol score indicated that he had engaged in binge drinking (6+ drinks) at T1. However, at T2 Alan’s score suggests that he had made considerable reductions in the use of both substances. Also his MAP scores for parental conflict and drug dealing suggest that he had also made major positive changes in the relevant domains of personal and social functioning as well as ceasing criminal behaviour.

At 3 months post-discharge I contacted Alan by phone. He had maintained and continued to further his progress. His drug use was at a minimal level (1 or 2 shared joints per month). He was no longer engaged in crime and his probationary period with the judicial system had passed. He had received a caution for his earlier drugs charge. At the time of follow-up he was enjoying participating in a Sports Coaching course and was excelling with his study assignments. Relationships had improved considerably with his mother and sister and he had re-engaged with a previous, positive, peer group linked to his involvement with the GAA . Overall he felt he was doing extremely well.

11. Complicating Factors with A-CRA Model

There are many challenges that may arise in the treatment of substance use disorders that can serve as barriers to successful treatment. These include acute or chronic cognitive deficits, health problems, social stressors and a lack of social resources [7] . Among individuals presenting with substance use there are often other significant life challenges including early school leaving, family conflicts, legal issues, poor or deviant social networks, etc. A particular challenge with Alan’s case was the social and environmental milieu which he shared with his drug using peers. For Alan, who initially had few skills and resources, engaging in treatment meant not only being asked to change his overall way of life but also to renounce some of those components in which he enjoyed a sense of belonging, particularly as he had invested significantly in these friendships. A sense of ‘belonging to the substance use culture’ can increase ambivalence for change [7] . Alan’s mother strongly disapproved of his drug using peer group and failed to acknowledge Alan’s perceived loss. This resulted in mother- son conflict. The use of the caregiver session allowed an exploration of perceived ‘losses’ relative to the ‘gains’ associated with Alan’s abstinence. It was moreover seen to be critical to establish alternatives for achieving a sense of belonging, including both his social connection and his social effectiveness. Alan’s sports ability allowed for this to be fostered. He is a talented sportsman which often meant his acceptance within a team or group is a given.

Despite the positive effects of A-CRA it is not without its shortcomings. The approach is at times quite American- oriented, particularly around identifying local resources and its focus on culturally specific outlets in promoting social engagement as alternatives to substance use. While this is supported in the literature, it may not necessarily be transferable to certain Irish adolescent contexts or subcultures.

12. Treatment Implications of the Case

A-CRA captures a broad range of behavioural treatments including those targeting operant learning processes, motivational barriers to improvement and other more traditional elements of cognitivebehavioural interventions. Overall, this intervention has demonstrated efficacy. Despite this heterogeneity, core elements emerge based in a conceptual model of SUDs as disorders characterized by learning processes and driven by the strongly reinforcing effects of the substances of abuse. There is rich evidence in the substance use disorders literature that improvement achieved by CBT (7) and indeed A-CRA (Godley et al. and Garner et al. [22 , 20] ) generalizes to all areas of functioning, including social, work, family and marital adjustment domains. The present study’s finding that a reduction in substance-related symptoms was accompanied by improved levels of functioning, social adjustment and enhanced quality of life, provides further support for this point.

In conclusion, there is some preliminary evidence that A-CRA is a promising treatment in the rehabilitation of adolescent substance users in Ireland and culturally similar societies. Clearly, results from a case study have limited generalisability and there is need for larger controlled studies providing robust outcomes to confirm the efficacy of A-CRA in an Irish context. A more systematic study of this issue is in the interest of adolescent substance users and the health services providers faced with the challenge of providing affordable, evidencebased mental health and addiction care to young people.

13. Recommendations to Clinicians and Students

The ACRA model is a structured assemblage of a range of cognitive and behavioural activities (e.g. a rationale and overview of the paradigm, sobriety sampling, functional analyses, communication skills, problem solving skills, refusal skills, jobs counselling, anger management and relapse prevention) which are shared in varying degrees with other CBT approaches. The ACRA model has the advantage of established effectiveness. A foundation in empirical research together with its manual- supported approach results in it being an appropriate “off the shelf ” intervention, highly applicable to many adolescent substance misusers. Such a focussed approach also has the advantage of limiting therapist “drift”. Notwithstanding the accessible manual and other resources available on- line, clinicians and students are strongly encouraged to undergo accredited ACRA training and supervision.

Unfortunately such a structured model, despite its many advantages, does have limitations. This model may not meet the sum of all drug misusing adolescent service user treatment needs, nor is it applicable to all adolescent drug users, particularly highly chaotic individuals with high levels of co- morbidities or multi-morbidities as often found in this population [29 , 30] . Whilst focussing on specifically on drug use, ACRA does not directly address co-existing problem behaviours or challenges such as depression, anxiety, personality disorder, or post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) synergistically linked to drug use. It is possible that given the high levels of dual diagnoses encountered in this population as well as the compounding effect that drug use exerts on multiple systems, clinicians and practitioners may find a strict application of the ACRA model limiting, necessitating the application of an additional range or layer of psychotherapeutic competencies? Additionally the ACRA model does not focus explicitly on other psychological activities useful in the treatment of drug misuse such as the control and management of unhelpful cognitive styles or habits; breathing or progressive relaxation skills; anger management; imagery, visualisation and mindfulness. That is, as a manual based approach comprising a number of fixed components, a major potential challenge facing clinicians and students is the tension they may experience between maintaining strict fidelity to a pure ACRA approach, versus the flexibility l approved by more formulation driven CBT approaches?

The advantages of a skilled application of a formulation driven approach which are cited and summarised in are multiple and include the collaborative nature of goal setting, the facilitation of problem prioritisation in a meaningful and useful manner; a more immediate direction and structuring of the course of treatment; the provision of a rationale for the most fitting intervention point or spotlight for the treatment; an integration of seemingly unrelated or dissimilar difficulties in a meaningful yet parsimonious fashion; an influence on the choice of procedures and “homework” exercises; theory based mechanisms to understand the dynamics of the therapeutic relationship and a sense of targeted and ‘extra-therapeutic’ issues and how they could be best explained and managed, especially in terms of precipitators or triggers, core beliefs, assumptions and automatic thoughts.

Thus given the above observations and together with the importance placed on engagement and retention, the high variability in the cognitive, emotional, social and developmental domains [4] differences in roles (e.g. teenagers who are also parents) and levels of autonomy as well as high degrees of dual diagnosis or co- morbidities found in this group [29 , 30] practitioners are encouraged to also develop competencies in allied psychological treatment models such as Motivational Interviewing [31] ; familiarity with the core principles of CBT, disorder specific and problem-specific CBT competences, the generic and meta- competences of CBT as well as an advanced knowledge and understanding of mental health problems that will provide practitioners with the confidence and capacity to implement treatment models in a more flexible yet coherent manner,. In addition to seeking supervision and mentorship students and practitioners are directed, as a starting point, to University College London’s excellent resources outlining the competencies required to provide a more comprehensive interventions [11] .

Both authors reported no conflict of interest in the content of this paper.

Author Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: JI. Recruitment & assessment and on going treatment t of patient JI. On going supervision of case KD. Contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools: JI, & KD. Wrote the paper: JI. Contributed to final draft paper KD.

Acknowledgments

We thank Adolescent Addiction Services, Health Service Executive.

- Compton WM, Thomas YF, Stinson FS, Grant BF (2007) Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV drug abuse and dependence in the United States: results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry 64: 566-576. View

- Hasin DS, Stinson FS, Ogburn E, Grant BF (2007) Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence in the United States: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry 64: 830-842. View

- Carroll KM, Nich C, Ball SA, McCance E, Frankforter TL, et al. (2000) Oneyear follow-up of disulfiram and psychotherapy for cocaine-alcohol users: sustained effects of treatment. Addiction 95: 1335-1349. View

- Stetler CB, Ritchie J, Rycroft-Malone J, Schultz A, Charns M (2007) Improving quality of care through routine, successful implementation of evidence-based practice at the bedside: an organizational case study protocol using the Pettigrew and Whipp model of strategic change. Imp Sci 2: 1-13. View

- Carroll KM, Fenton LR, Ball SA, Nich C, Frankforter TL, et al. (2004) Efficacy of disulfiram and cognitive behavior therapy in cocaine-dependent outpatients: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry 61: 264-272. View

- Carroll KM, Ball SA, Martino S, Nich C, Babuscio TA, et al. (2008) Computer-assisted delivery of cognitive-behavioral therapy for addiction: a randomized trial of CBT4CBT. Am J Psychiatry 165: 881-888. View

- McHugh RK, Hearon BA, Otto MW (2010) Cognitive behavioral therapy for substance use disorders. Psychiatr Clin North Am 33: 511-525. View

- Waldron HB, Kaminer Y (2004) On the learning curve: the emerging evidence supporting cognitive-behavioral therapies for adolescent substance abuse. Addiction 99 Suppl 2: 93-105. View

- Freeman A, Reinecke MA (1995) Cognitive therapy. New York: Guilford Press.

- Stephens RS, Babor TF, Kadden R, Miller M; Marijuana Treatment Project Research Group (2002) The Marijuana Treatment Project: rationale, design and participant characteristics. Addiction 97 Suppl 1: 109-124. View

- Pilling S, Hesketh K, Mitcheson L (2009) Psychosocial interventions in drug misuse: a framework and toolkit for implementing NICE-recommended treatment interventions. London: British Psychological Society, Centre for Outcomes, Research and Effectiveness (CORE) Research Department of Clinical, Educational and Health Psychology, University College. View

- Azrin NH (1976) Improvements in the community-reinforcement approach to alcoholism. Behav Res Ther 14: 339-348. View

- Hunt GM, Azrin NH (1973) A community-reinforcement approach to alcoholism. Behav Res Ther 11: 91-104. View

- Azrin NH, Sisson RW, Meyers R, Godley M (1982) Alcoholism treatment by disulfiram and community reinforcement therapy. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry 13: 105-112. View

- Meyers RJ, Miller WR (2001) A community reinforcement approach to addiction treatment: (International Research Monographs in the Addictions) Cambridge Univ Press.

- Mallams JH, Godley MD, Hall GM, Meyers RJ (1982) A social-systems approach to resocializing alcoholics in the community. J Stud Alcohol 43: 1115-1123.

- Finney JW, Monahan SC (1996) The cost-effectiveness of treatment for alcoholism: a second approximation. J Stud Alcohol 57: 229-243. View

- Rollnick S, Miller WR (1999) What is motivational interviewing? Behav Cogn Psychotherapy. 23: 325-334. View

- Garner BR, Barnes B, Godley SH (2009) Monitoring fidelity in the Adolescent Community Reinforcement Approach (A-CRA): the training process for A-CRA raters. J Behav Anal Health Fit Med 2: 43-54. View

- Dennis M, Godley SH, Diamond G, Tims FM, Babor T, et al. (2004) The Cannabis Youth Treatment (CYT) Study: main findings from two randomized trials. J Subst Abuse Treat 27: 197-213. View

- Garner BR, Godley MD, Funk RR, Dennis ML, Godley SH (2007) The impact of continuing care adherence on environmental risks, substance use, and substance-related problems following adolescent residential treatment. Psychol Addict Behav. 21: 488-497. View

- Slesnick N, Prestopnik JL, Meyers RJ, Glassman M (2007) Treatment outcome for street-living, homeless youth. Addict Behav 32: 1237-1251. View

- Beck AT, Hollon SD, Young JE, Bedrosian RC, Budenz D (1985) Treatment of depression with cognitive therapy and amitriptyline. Arch Gen Psychiatry 42: 142-148. View

- Smith C (1998) Assessing health needs in women's prisons. PSJ 224.

- Maude-Griffin PM1, Hohenstein JM, Humfleet GL, Reilly PM, Tusel DJ, et al. (1998) Superior efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy for urban crack cocaine abusers: main and matching effects. J Consult Clin Psychol 66: 832-837. View

- Godley SH, Meyers RJ, Smith JE, Karvinen T, Titus JC, et al. (2001) The adolescent community reinforcement approach for adolescent cannabis users: US Department of Health and Human Services. View

- Carroll KM (1998) A cognitive-behavioral approach: Treating cocaine addiction. National Institute on Drug Abuse. View

- Bukstein OG, Glancy LJ, Kaminer Y (1992) Pattern of affective comorbidity in a clinical population of dually diagonised adolescent substance abusers. J Ame Aca Child Adol Psychiat 31: 1041-1045. View

- Kaminer Y, Burleson JA, Goldberger R (2002) Psychotherapies for adolescent substance abusers: Short- and long-term outcomes. J Nerv Ment Dis 190: 737-745.

- Miller WR, Rollnick S (2002) Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford Press. View

- Presidential Message

- Nominations/Elections

- Past Presidents

- Member Spotlight

- Fellow List

- Fellowship Nominations

- Current Awardees

- Award Nominations

- SCP Mentoring Program

- SCP Book Club

- Pub Fee & Certificate Purchases

- LEAD Program

- Introduction

- Find a Treatment

- Submit Proposal

- Dissemination and Implementation

- Diversity Resources

- Graduate School Applicants

- Student Resources

- Early Career Resources

- Principles for Training in Evidence-Based Psychology

- Advances in Psychotherapy

- Announcements

- Submit Blog

- Student Blog

- The Clinical Psychologist

- CP:SP Journal

- APA Convention

- SCP Conference

CASE STUDY Richard (bipolar disorder, substance use disorder)

Case study details.

Richard is a 62-year-old single man who says that his substance dependence and his bipolar disorder both emerged in his late teens. He says that he started to drink to “feel better” when his episodes of depression made it hard for him to interact with his peers. He also states that alcohol and cocaine are a natural part of his manic episodes. He also notes that coming off the cocaine and binge drinking contribute to low mood, but he has not responded well to referrals to AA and past inpatient stays have led to only temporary abstinence. Yet, Richard is now trying to forge a closer relationship to his adult children, and he says he is especially motivated to get a better handle on both his bipolar disorder and his substance use. He has been more compliant with his mood stabilizing and antidepressant medication, and his psychiatrist would like his dual diagnoses addressed with psychotherapy.

- Alcohol Use

- Elevated Mood

- Impulsivity

- Mania/Hypomania

- Mood Cycles

- Substance Abuse

Diagnoses and Related Treatments

1. bipolar disorder, 2. mixed substance use/dependence.

Thank you for supporting the Society of Clinical Psychology. To enhance our membership benefits, we are requesting that members fill out their profile in full. This will help the Division to gather appropriate data to provide you with the best benefits. You will be able to access all other areas of the website, once your profile is submitted. Thank you and please feel free to email the Central Office at [email protected] if you have any questions

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Immediate Communication

- Published: 14 September 2020

COVID-19 risk and outcomes in patients with substance use disorders: analyses from electronic health records in the United States

- Quan Qiu Wang 1 ,

- David C. Kaelber 2 ,

- Rong Xu ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3127-4795 1 &

- Nora D. Volkow ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6668-0908 3

Molecular Psychiatry volume 26 , pages 30–39 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

48k Accesses

400 Citations

1066 Altmetric

Metrics details

A Correction to this article was published on 30 September 2020

This article has been updated

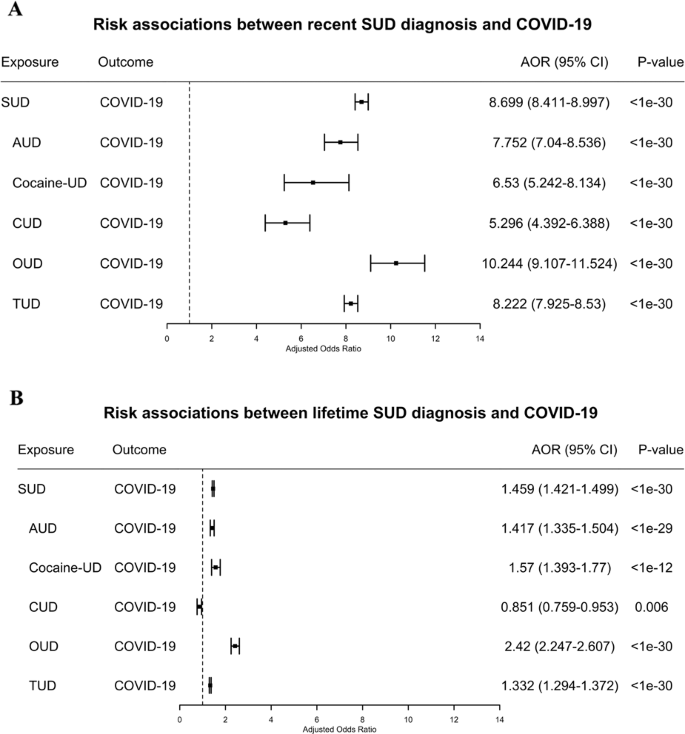

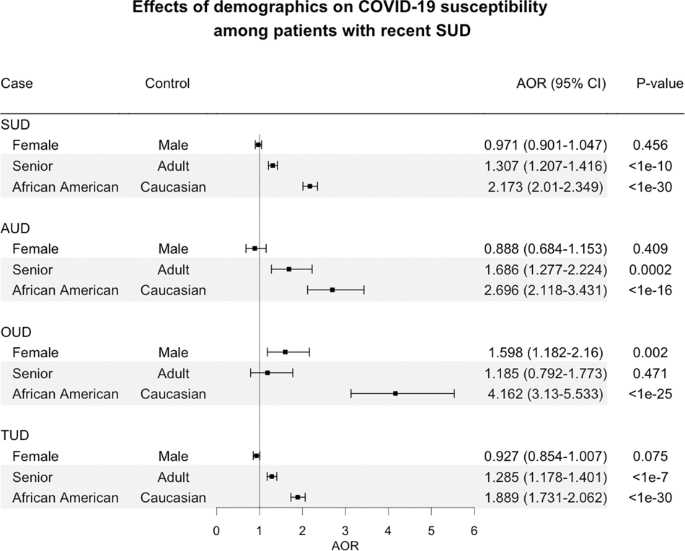

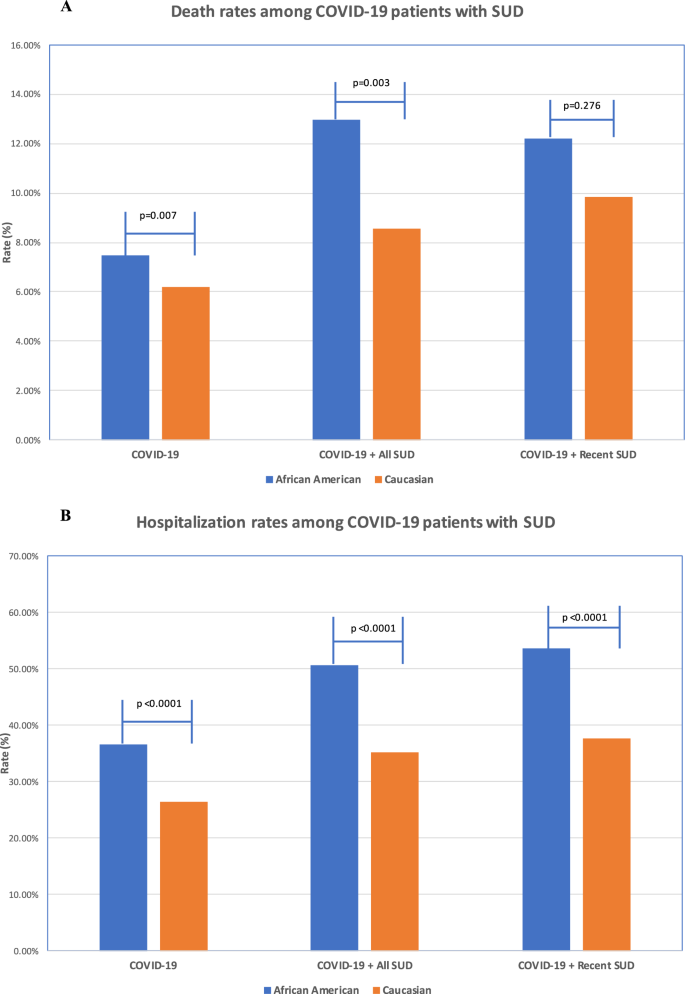

The global pandemic of COVID-19 is colliding with the epidemic of opioid use disorders (OUD) and other substance use disorders (SUD) in the United States (US). Currently, there is limited data on risks, disparity, and outcomes for COVID-19 in individuals suffering from SUD. This is a retrospective case-control study of electronic health records (EHRs) data of 73,099,850 unique patients, of whom 12,030 had a diagnosis of COVID-19. Patients with a recent diagnosis of SUD (within past year) were at significantly increased risk for COVID-19 (adjusted odds ratio or AOR = 8.699 [8.411–8.997], P < 10 −30 ), an effect that was strongest for individuals with OUD (AOR = 10.244 [9.107–11.524], P < 10 −30 ), followed by individuals with tobacco use disorder (TUD) (AOR = 8.222 ([7.925–8.530], P < 10 −30 ). Compared to patients without SUD, patients with SUD had significantly higher prevalence of chronic kidney, liver, lung diseases, cardiovascular diseases, type 2 diabetes, obesity and cancer. Among patients with recent diagnosis of SUD, African Americans had significantly higher risk of COVID-19 than Caucasians (AOR = 2.173 [2.01–2.349], P < 10 −30 ), with strongest effect for OUD (AOR = 4.162 [3.13–5.533], P < 10 −25 ). COVID-19 patients with SUD had significantly worse outcomes (death: 9.6%, hospitalization: 41.0%) than general COVID-19 patients (death: 6.6%, hospitalization: 30.1%) and African Americans with COVID-19 and SUD had worse outcomes (death: 13.0%, hospitalization: 50.7%) than Caucasians (death: 8.6%, hospitalization: 35.2%). These findings identify individuals with SUD, especially individuals with OUD and African Americans, as having increased risk for COVID-19 and its adverse outcomes, highlighting the need to screen and treat individuals with SUD as part of the strategy to control the pandemic while ensuring no disparities in access to healthcare support.

Similar content being viewed by others

Association of COVID-19 with endocarditis in patients with cocaine or opioid use disorders in the US

Associations between classic psychedelics and opioid use disorder in a nationally-representative U.S. adult sample

Medical and genetic correlates of long-term buprenorphine treatment in the electronic health records

Introduction.

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and has rapidly escalated into a global pandemic [ 1 ]. The global pandemic of COVID-19 is colliding in the United States (US) with the epidemic of opioid use disorders (OUD) and overdose mortality [ 2 , 3 , 4 ]. Currently, there is little if any quantitative analysis of the risks and outcomes for COVID-19 infection in individuals suffering from an OUD and those suffering from other substance use in the US. In addition, there is minimal data on how race and other demographic factors affect the risk and outcomes of COVID-19 among patients with SUD including OUD.

It is estimated that more than 70,000 people will die in the US from an overdose in 2019 mostly from opioid overdoses, which are driven by the respiratory depressant effects of opioids. Considering that COVID-19 affects pulmonary function this combination could be particularly lethal. Additionally, ~10.8% of adults in the US have a substance use disorders (SUD) including alcohol (AUD) and tobacco (TUD) [ 5 ]. To the extent that chronic use of tobacco, alcohol and other drugs is associated with cardiovascular (arrhythmias, cardiac insufficiency, and myocardial infarction), pulmonary (COPD, pulmonary hypertension), and metabolic diseases (diabetes, hypertension) [ 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 ] all of which are risk factors for COVID-19 infection and for worse outcomes [ 11 , 12 , 13 ] one can also predict that individuals with SUD including OUD would be at increased risk for adverse COVID-19 outcomes [ 2 ]. Preliminary reports regarding higher risk for adverse outcomes with COVID-19 and smoking have been inconclusive [ 14 , 15 , 16 ]. Currently there is little research on the effects of other drugs including opioids, cannabis, cocaine and alcohol on the susceptibility to COVID-19 infection and to adverse outcomes [ 2 ].

Material and methods

Database description.

We performed a retrospective case-control study using de-identified population-level electronic health record (EHR) data collected by the IBM Watson Health Explorys from 360 hospitals and 317,000 providers across 50 states in the US since 1999 [ 17 ]. The EHRs are de-identified according to the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act and the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act standards. After the de-identification process, curation process normalizes the data through mapping key elements to widely-accepted standards [ 18 ]. Specifically, disease terms are coded using the Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine-Clinical Terms (SNOMED-CT), a global standard for health terms that provides the core general terminology for EHRs [ 19 ]. Previous studies showed that with this large-scale and standardized EHR database, large case-control studies can be undertaken efficiently [ 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 ], including our recent studies [ 23 , 24 ].

Study population

At the time of this study (June 15, 2020), the study population consisted of 73,099,850 unique patients, including 7,510,380 patients with a diagnosis with SUD (diagnosis made within the past year or prior) of whom 722,370 had been recently diagnosed with SUD (diagnosed within past year), 12,030 patients diagnosed with COVID-19, 1880 patients with lifetime diagnosis of SUD and COVID-19, and 1050 with recent SUD diagnosis and COVID-19. The status of COVID-19 was based on the concept “Coronavirus infection (disorder)” (SNOMED-CT Concept Code 186747009) and we further limited the diagnosis time frame to within the past year to capture the timing of new cases arising during the COVID-19 pandemic. The outcome measures were COVID-19 diagnosis, rates of death, and hospitalization. The specific types of SUD examined included alcohol use disorder (AUD), OUD, tobacco use disorder (TUD), cannabis use disorder (CUD), and cocaine use disorder (Cocaine-UD). Other types of SUDs were not investigated due to their small number of COVID-19 cases.