- Create new account

- Reset your password

Register and get FREE resources and activities

Ready to unlock all our resources?

The beginner's guide to primary-school homework

What’s the point of homework?

For many families, homework is a nightly battle, but primary schools set it for a variety of reasons. ‘It helps to consolidate the skills that are being taught at school, and provides children with additional revision opportunities,’ explains head teacher Steph Matthews of St Paul’s CofE School, Gloucester .

‘It also gives children an opportunity to explore learning in an unstructured setting, encouraging them to be independent and follow their own lines of enquiry.’ In addition, homework creates a partnership between school and family, giving parents an insight into what their child is learning.

How much homework should my child get in primary school?

In the past, the Department for Education advised that Key Stage 1 children should do an hour of homework each week, rising to half an hour per night in Key Stage 2. This advice was scrapped in 2012, giving schools more freedom, but many still follow the old guidelines.

In Reception , formal homework is rarely set. However, children are likely to bring home books to share with the family, first reading books, and/or keywords to learn.

In Years 1 and 2 , children are likely to have one or two tasks per week. This could be literacy or numeracy worksheets (for example an exercise where children have to compare the weights of different household items), a short piece of writing (such as a recount of a school trip) or work relating to the class topic (find out five facts about the Great Fire of London ).

In Years 3 and 4 , most schools set two homework activities each week: typically, one literacy (such as a worksheet on collective nouns, or a book review ) and one numeracy (a worksheet on bar charts).

In Years 5 and 6 , children may have two or three pieces of homework each week. ‘The amount begins to increase to prepare children for SATs and the transition to secondary school,’ says Steph. These activities might include maths worksheets, researching a topic, book reviews and grammar exercises.

Alongside formal homework tasks, most children bring home reading scheme books from Reception onwards, with weekly spellings and times tables from Year 1 or 2.

Learning logs and homework challenges

Not all schools rely on handing out worksheets. Learning logs or challenges are becoming more popular: children are given a folder of suggested activities – from writing a poem to building a model castle – and must choose a certain number to complete throughout the term.

Other schools ensure that homework ties in with the current class topic. ‘We have a themed approach, and set homework activities that give opportunities to explore the topic in a fun way, for example, designing a method of transport that Phileas Fogg could use to travel the world,’ explains Steph.

Modern homework methods

Unsurprisingly, technology is playing an increasingly important part in homework. Some schools use online reading schemes such as Bug Club , where teachers allocate e-books of the appropriate level, or subscription services like SAM Learning to set cross-curricular tasks.

A growing number also set homework electronically , with children logging into the school website to download their task.

What if the homework is too much – or too hard?

If you feel your child is overloaded with homework, speak to the teacher. ‘Forcing children to complete homework is counterproductive, because they come to perceive it as a chore,’ says Rod Grant, head teacher of Clifton Hall School, Edinburgh . ‘This makes learning appear boring, arduous or both, and that is really dangerous, in my view.’

Most schools publish their homework policy on the school website , telling parents exactly what to expect. ‘Teachers should make their expectations very clear in terms of deadlines and how long it should take, and should also differentiate tasks to suit the level of the pupil,’ adds Steph.

No homework at all?

If your child doesn’t get any homework, you may feel out of touch with his learning, or concerned that he isn’t being challenged. But there are good reasons why some schools don’t set homework, or set it only occasionally, says Rod. ‘Although homework can be beneficial, family life tends to suffer as a result of it being imposed,’ he explains. ‘ If a school isn’t providing homework, there’s plenty that parents can do at home instead : reading with their children, doing number puzzles on car journeys, using online resources, and so on.’

Parents may also worry that without doing homework, children won’t develop study habits for later life. ‘There is genuinely no need for a six-year-old to get into a routine of working at home; there’s time to learn that later,’ Rod advises. ‘Parents need to relax and encourage children to love learning – and that comes when learning is fun, relevant and engaging, not through doing homework tasks that are unchallenging, or secretarial in nature.’

Homework: advice and support for primary-school parents

For information and support on all aspects of homework, from managing other siblings to helping with specific subjects, head to our Homework area.

Give your child a headstart

- FREE articles & expert information

- FREE resources & activities

- FREE homework help

More like this

- Our Mission

What’s the Right Amount of Homework?

Decades of research show that homework has some benefits, especially for students in middle and high school—but there are risks to assigning too much.

Many teachers and parents believe that homework helps students build study skills and review concepts learned in class. Others see homework as disruptive and unnecessary, leading to burnout and turning kids off to school. Decades of research show that the issue is more nuanced and complex than most people think: Homework is beneficial, but only to a degree. Students in high school gain the most, while younger kids benefit much less.

The National PTA and the National Education Association support the “ 10-minute homework guideline ”—a nightly 10 minutes of homework per grade level. But many teachers and parents are quick to point out that what matters is the quality of the homework assigned and how well it meets students’ needs, not the amount of time spent on it.

The guideline doesn’t account for students who may need to spend more—or less—time on assignments. In class, teachers can make adjustments to support struggling students, but at home, an assignment that takes one student 30 minutes to complete may take another twice as much time—often for reasons beyond their control. And homework can widen the achievement gap, putting students from low-income households and students with learning disabilities at a disadvantage.

However, the 10-minute guideline is useful in setting a limit: When kids spend too much time on homework, there are real consequences to consider.

Small Benefits for Elementary Students

As young children begin school, the focus should be on cultivating a love of learning, and assigning too much homework can undermine that goal. And young students often don’t have the study skills to benefit fully from homework, so it may be a poor use of time (Cooper, 1989 ; Cooper et al., 2006 ; Marzano & Pickering, 2007 ). A more effective activity may be nightly reading, especially if parents are involved. The benefits of reading are clear: If students aren’t proficient readers by the end of third grade, they’re less likely to succeed academically and graduate from high school (Fiester, 2013 ).

For second-grade teacher Jacqueline Fiorentino, the minor benefits of homework did not outweigh the potential drawback of turning young children against school at an early age, so she experimented with dropping mandatory homework. “Something surprising happened: They started doing more work at home,” Fiorentino writes . “This inspiring group of 8-year-olds used their newfound free time to explore subjects and topics of interest to them.” She encouraged her students to read at home and offered optional homework to extend classroom lessons and help them review material.

Moderate Benefits for Middle School Students

As students mature and develop the study skills necessary to delve deeply into a topic—and to retain what they learn—they also benefit more from homework. Nightly assignments can help prepare them for scholarly work, and research shows that homework can have moderate benefits for middle school students (Cooper et al., 2006 ). Recent research also shows that online math homework, which can be designed to adapt to students’ levels of understanding, can significantly boost test scores (Roschelle et al., 2016 ).

There are risks to assigning too much, however: A 2015 study found that when middle school students were assigned more than 90 to 100 minutes of daily homework, their math and science test scores began to decline (Fernández-Alonso, Suárez-Álvarez, & Muñiz, 2015 ). Crossing that upper limit can drain student motivation and focus. The researchers recommend that “homework should present a certain level of challenge or difficulty, without being so challenging that it discourages effort.” Teachers should avoid low-effort, repetitive assignments, and assign homework “with the aim of instilling work habits and promoting autonomous, self-directed learning.”

In other words, it’s the quality of homework that matters, not the quantity. Brian Sztabnik, a veteran middle and high school English teacher, suggests that teachers take a step back and ask themselves these five questions :

- How long will it take to complete?

- Have all learners been considered?

- Will an assignment encourage future success?

- Will an assignment place material in a context the classroom cannot?

- Does an assignment offer support when a teacher is not there?

More Benefits for High School Students, but Risks as Well

By the time they reach high school, students should be well on their way to becoming independent learners, so homework does provide a boost to learning at this age, as long as it isn’t overwhelming (Cooper et al., 2006 ; Marzano & Pickering, 2007 ). When students spend too much time on homework—more than two hours each night—it takes up valuable time to rest and spend time with family and friends. A 2013 study found that high school students can experience serious mental and physical health problems, from higher stress levels to sleep deprivation, when assigned too much homework (Galloway, Conner, & Pope, 2013 ).

Homework in high school should always relate to the lesson and be doable without any assistance, and feedback should be clear and explicit.

Teachers should also keep in mind that not all students have equal opportunities to finish their homework at home, so incomplete homework may not be a true reflection of their learning—it may be more a result of issues they face outside of school. They may be hindered by issues such as lack of a quiet space at home, resources such as a computer or broadband connectivity, or parental support (OECD, 2014 ). In such cases, giving low homework scores may be unfair.

Since the quantities of time discussed here are totals, teachers in middle and high school should be aware of how much homework other teachers are assigning. It may seem reasonable to assign 30 minutes of daily homework, but across six subjects, that’s three hours—far above a reasonable amount even for a high school senior. Psychologist Maurice Elias sees this as a common mistake: Individual teachers create homework policies that in aggregate can overwhelm students. He suggests that teachers work together to develop a school-wide homework policy and make it a key topic of back-to-school night and the first parent-teacher conferences of the school year.

Parents Play a Key Role

Homework can be a powerful tool to help parents become more involved in their child’s learning (Walker et al., 2004 ). It can provide insights into a child’s strengths and interests, and can also encourage conversations about a child’s life at school. If a parent has positive attitudes toward homework, their children are more likely to share those same values, promoting academic success.

But it’s also possible for parents to be overbearing, putting too much emphasis on test scores or grades, which can be disruptive for children (Madjar, Shklar, & Moshe, 2015 ). Parents should avoid being overly intrusive or controlling—students report feeling less motivated to learn when they don’t have enough space and autonomy to do their homework (Orkin, May, & Wolf, 2017 ; Patall, Cooper, & Robinson, 2008 ; Silinskas & Kikas, 2017 ). So while homework can encourage parents to be more involved with their kids, it’s important to not make it a source of conflict.

A community blog focused on educational excellence and equity

About the topic

Explore classroom guidance, techniques, and activities to help you meet the needs of ALL students.

most recent articles

Shaking Up High School Math

Executive Functions and Literacy Skills in the Classroom

Connecting and Communicating With Families to Help Break Down Barriers to Learning

Discover new tools and materials to integrate into you instruction.

Culture, Community, and Collaboration

Vertical Progression of Math Strategies – Building Teacher Understanding

“Can I have this? Can I have that?”

Find instructions and recommendations on how to adapt your existing materials to better align to college- and career-ready standards.

To Teach the Truth

Helping Our Students See Themselves and the World Through the Books They Read in Our Classrooms

Textbooks: Who Needs Them?

Learn what it means for instructional materials and assessment to be aligned to college- and career-ready standards.

Let’s Not Make Power ELA/Literacy Standards and Talk About Why We Didn’t

What to Consider if You’re Adopting a New ELA/Literacy Curriculum

Not Your Mom’s Professional Development

Delve into new research and perspectives on instructional materials and practice.

Summer Reading Club 2023

Synergy between College and Career Readiness Standards-Aligned Instruction and Culturally Relevant Pedagogy

Children Should be Seen AND Heard

- Submissions Guidelines

- About the Blog

Designing Effective Homework

Best practices for creating homework that raises student achievement

Homework. It can be challenging…and not just for students. For teachers, designing homework can be a daunting task with lots of unanswered questions: How much should I assign? What type of content should I cover? Why aren’t students doing the work I assign? Homework can be a powerful opportunity to reinforce the Shifts in your instruction and promote standards-aligned learning, but how do we avoid the pitfalls that make key learning opportunities sources of stress and antipathy?

The nonprofit Instruction Partners recently set out to answer some of these questions, looking at what research says about what works when it comes to homework. You can view their original presentation here , but I’ve summarized some of the key findings you can put to use with your students immediately.

Does homework help?

Consistent homework completion has been shown to increase student achievement rates—but frequency matters. Students who are given homework regularly show greater gains than those who only receive homework sporadically. Researchers hypothesize that this is due to improved study skills and routines practiced through homework that allow students to perform better academically.

Average gains on unit tests for students who completed homework were six percentile points in grades 4–6, 12 percentile points in grades 7–9, and an impressive 24 percentile points in grades 10–12; so yes, homework (done well) does work. [i]

What should homework cover?

While there is little research about exactly what types of homework content lead to the biggest achievement gains, there are some general rules of thumb about how homework should change gradually over time.

In grades 1–5, homework should:

- Reinforce and allow students to practice skills learned in the classroom

- Help students develop good study habits and routines

- Foster positive feelings about school

In grades 6–12, homework should:

- Prepare students for engagement and discussion during the next lesson

- Allow students to apply their skills in new and more challenging ways

The most often-heard criticism of homework assignments is that they simply take too long. So how much homework should you assign in order to see results for students? Not surprisingly, it varies by grade. Assign 10-20 minutes of homework per night total, starting in first grade, and then add 10 minutes for each additional grade. [ii] Doing more can result in student stress, frustration, and disengagement, particularly in the early grades.

Why are some students not doing the homework?

There are any number of reasons why students may not complete homework, from lack of motivation to lack of content knowledge, but one issue to watch out for as a teacher is the impact of economic disparities on the ability to complete homework.

Multiple studies [iii] have shown that low-income students complete homework less often than students who come from wealthier families. This can lead to increased achievement gaps between students. Students from low-income families may face additional challenges when it comes to completing homework such as lack of access to the internet, lack of access to outside tutors or assistance, and additional jobs or family responsibilities.

While you can’t erase these challenges for your students, you can design homework that takes those issues into account by creating homework that can be done offline, independently, and in a reasonable timeframe. With those design principles in mind, you increase the opportunity for all your students to complete and benefit from the homework you assign.

The Big Picture

Perhaps most importantly, students benefit from receiving feedback from you, their teacher, on their assignments. Praise or rewards simply for homework completion have little effect on student achievement, but feedback that helps them improve or reinforces strong performance does. Consider keeping this mini-table handy as you design homework:

The act of assigning homework doesn’t automatically raise student achievement, so be a critical consumer of the homework products that come as part of your curriculum. If they assign too much (or too little!) work or reflect some of these common pitfalls, take action to make assignments that better serve your students.

[i] Cooper, H. (2007). The battle over homework (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

[ii] Cooper, H. (1989a). Homework .White Plains, NY: Longman.

[iii] Horrigan, T. (2015). The numbers behind the broadband ‘homework gap’ http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2015/04/20/the-numbers-behind-the-broadband-homework-gap/ and Miami Dade Public Schools. (2009). Literature Review: Homework. http://drs.dadeschools.net/LiteratureReviews/Homework.pdf

- ELA / Literacy

- Elementary School

- High School

- Mathematics

- Middle School

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

About the Author: Claire Rivero is the Digital Strategy Manager for Student Achievement Partners. Claire leads the organization’s communications and digital promotion work across various channels including email, Facebook, Twitter, and Pinterest, always seeking new ways to reach educators. She also manages Achieve the Core’s blog, Aligned. Prior to joining Student Achievement Partners, Claire worked in the Communications department for the American Red Cross and as a literacy instructor in a London pilot program. Claire holds bachelor’s degrees in English and Public Policy from Duke University and a master’s degree in Social Policy (with a concentration on Education Policy) from the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Stay In Touch

Like what you’re reading? Sign up to receive emails about new posts, free resources, and advice from educators.

About The Education Hub

- Course info

- Your courses

- ____________________________

- Using our resources

- Login / Account

Homework for primary school students

- Curriculum integration

- Health, PE & relationships

- Literacy (primary level)

- Practice: early literacy

- Literacy (secondary level)

- Mathematics

Diverse learners

- Gifted and talented

- Neurodiversity

- Speech and language differences

- Trauma-informed practice

- Executive function

- Movement and learning

- Science of learning

- Self-efficacy

- Self-regulation

- Social connection

- Social-emotional learning

- Principles of assessment

- Assessment for learning

- Measuring progress

- Self-assessment

Instruction and pedagogy

- Classroom management

- Culturally responsive pedagogy

- Co-operative learning

- High-expectation teaching

- Philosophical approaches

- Planning and instructional design

- Questioning

Relationships

- Home-school partnerships

- Student wellbeing NEW

- Transitions

Teacher development

- Instructional coaching

- Professional learning communities

- Teacher inquiry

- Teacher wellbeing

- Instructional leadership

- Strategic leadership

Learning environments

- Flexible spaces

- Neurodiversity in Primary Schools

- Neurodiversity in Secondary Schools

Homework is defined as tasks assigned to students by school teachers that are intended to be carried out during non-school hours [i] . Homework is a unique educational practice as it is the only learning strategy that crosses the boundary between the school and the home. Much virtue has been attributed to the practice of homework that has not been borne out by research. Both teachers and parents have strong feelings, both positive and negative, about the value of homework, and parents and teachers alike still confuse homework load with rigour, and compliance with responsibility. To further complicate matters, most teachers have never been trained in the effective use of homework, so tend to rely on the traditional types of tasks they experienced as students.

In recent years, the practice of homework has come under critical review, with public attitudes around the globe changing, and with the following international trends emerging:

- Eliminating homework in the first 2-3 years of primary school.

- Limiting homework to reading only in the first 6 years of primary school.

- Eliminating weekend or holiday homework at all levels.

Many of these changes in policy have occurred at the school or district level, but some countries have instituted these changes through government mandate.

Homework and families

The diversity of families makes the practice of homework even more complicated. Parents within the same community may differ in their beliefs about the place of academic work in life. Some parents prioritise academics (wanting more homework), others want a balance of academics and chosen activities, and others prioritise leisure and happiness (wanting less or no homework). There is also a growing parent activism around the world, driven by the role homework plays in children’s stress levels and an awareness of the need for balance in work, play, downtime and sleep. Parents are speaking out with concerns about ‘academic stress’ and work/life balance for students and, as a result, are demanding more control over their child’s free time. Parents are also pushing back against using extra homework as punishment for misbehaviour in the classroom and practices that punish students for not completing homework.

There are also concerns about homework as an equity issue. Economic differences can entrench privilege as children from wealthier families enjoy ready access to technology, tutors, and educated parents, while children of poverty may lack access to technology, materials, and favourable working conditions. A study by the OECD [ii] of students from 38 different countries showed that students from higher social classes did more homework than students from lower social classes. More affluent parents are also more likely to help with homework than less affluent parents, and families living in poverty often need to prioritise family responsibilities and paid work over homework.

In an effort to address the widening economic diversity of families and to accommodate different parental preferences, some traditional homework practices, such as punishing students for incomplete homework or for a parent’s failure to sign homework, assigning extra homework to students as punishment for classroom misbehaviour, and including homework as a prerequisite for grade or year completion, are being discontinued in primary schools. Other homework practices are gaining popularity in primary schools, such as:

- Allowing flexibility in when homework is due, moving away from daily homework to homework that may be turned in over several days.

- Differentiating homework for parents—providing additional resources for parents who desire additional work for their child (challenge packets, lists of websites) and allowing other parents to ‘opt out’ of homework, or to choose to limit the amount of time their child spends on homework.

- Providing more time during the school day or after school for students to complete homework at school. Some schools, especially those in high poverty communities, are extending the school day, so that all homework is completed at school.

The research on homework

The results of research about the benefit of homework to academic achievement are mixed, inconclusive, and sometimes contradictory. These results are not surprising given that homework involves the complex interaction of a number of factors, such as differences in children, teachers, tasks, home environments, measurements of learning, and the unique interaction between homework and classroom learning within individual students [iii] . The pervasive flaw of the early homework research was that it focused almost exclusively on the correlation between time and achievement, with no consideration of the type or quality of the homework task. That research failed to show that homework improves the academic performance of primary school students, and revealed that, up to a point, the correlation of homework time and achievement appeared positive, but past the optimum amount of time, achievement either remained flat or declined [iv] .

What was the optimum amount of time spent on homework? Curiously, the appropriate amount of homework for different year levels was consistent with a longstanding guideline called the 10-minute rule (origin unknown). The 10-minute rule is a guideline many schools follow that homework should not exceed 10 minutes per year level per night, all subjects combined. That is, a student in year one should be expected to complete no more than 10 minutes per night, while a student in year six should be expected to complete no more than 60 minutes per night [v] . Interestingly, there is no recommendation for any amount of new entrants’ homework by any educational group.

However, while the 10-minute rule may be helpful as an upper limit, it fails to take into account the quality of the task and differences in students’ working speeds. It is important to remember that correlation of time and achievement is not causation: it is impossible to show that homework causes higher achievement. Correlating time and achievement also ignores many any other variables that may affect achievement. After controlling for motivation, ability, quality of instruction, course work quantity, and some background variables, no meaningful effect of homework on achievement remained [vi] .

Due to such discrepancies and other flaws in homework studies, researchers disagree as to whether or not homework enhances achievement. While many hold strongly to their assertion that homework is beneficial, others point to newer studies that seem to discount early research. A new generation of homework studies using more sophisticated analyses and controlling for more variables often fail to find a significant relationship between homework time and achievement, especially with primary students [vii] .

Teachers should view the research through the lens of what they intuitively know about their students and apply the same principles of effective teaching and learning to homework that they would apply to the classroom. Teachers know that organisation and structure of learning matters, that feedback about learning is critical, that the quality of a learning task matters, and that student differences in developmental levels, learning preferences and persistence must be considered. Achievement is related not to the amount of homework or the time spent on it, but to the quality of the homework task, the student’s perception of the value of the task, and how interesting the task appears. In other words, task quality is what really matters.

Purposes of homework

If homework is given, it should be purposeful and meaningful, not just given for the sake of assigning homework. Before designing a homework task, teachers must first determine the purpose of the task. This may include pre-learning, diagnosis, checking for understanding, practice, or processing. Homework should not be used for new learning.

- Pre-learning: traditional preparation homework, such as reading or outlining a chapter before a discussion, was often used as background for a more in-depth lesson. A more engaging use of pre-learning would be to discover what students already know about a topic or what they are interested in learning about (such as asking them to write down questions they have about the digestive system). The most valuable use of pre-learning homework may be to stimulate interest in a concept (such as listing eye colour and hair colour of relatives for a genetics lesson).

- Diagnosis: how do we design learning if we don’t know where students are? Diagnostic homework may include pre-tests, a checklist of ‘I can’ statements, or a practice test to assess prerequisite skills. Diagnostic homework saves time—once teachers know where students are in their skills or knowledge, they can plan instruction more efficiently.

- Checking for understanding: this is probably the most neglected use of homework, yet it is the most valuable way for teachers to gain insight into student learning. For instance, journal questions about a science experiment may ask the student to explain what happened and why. Asking students to identify literary devices in a short story shows the teacher whether the student understands literary devices. Asking students to do a few sample problems in math and to explain the steps lets the teacher know if the student understands how to do the problem.

- Practice: the traditional use of homework has been for the practice of rote skills, such as multiplication tables, or things that need to be memorised, such as spelling words. Although practice is necessary for many rote skills, there are three mistakes that teachers sometimes make with the use of practice homework. First, teachers may believe they are giving practice homework when, in fact, the student did not understand the concept or skill in class. The homework then actually involves new learning and is often quite frustrating. Second, if teachers skip the step of checking for understanding, students may be practising something incorrectly and internalising misconceptions. For instance, students should practise math operations only after the teacher has adequately checked for understanding. Third, distributed practice is better than mass practice—that is, practice is more effective when distributed over several days. A smart practice for math is two-tiered homework: Part One is three problems to check for understanding of a new skill, and Part Two is 10 problems to practise a skill previously learned.

- Processing. Processing homework asks students to do something new with concepts or skills they have learned – to apply skills, reflect on concepts that were discussed in class, think of new questions to ask, or synthesise information. Processing homework may be a single task such as applying maths skills to a new word problem, or a long-term project such as demonstrating writing skills in an original essay or creating a schematic to show the relationship between major concepts in a unit.

Designing quality homework tasks

Creating quality homework tasks requires attention to four aspects:

- Academic purpose — Tasks should communicate a clear academic purpose.

- Efficiency — Tasks should help students reach the learning goal without wasting time or energy.

- Competence — Tasks should have a positive effect on a student’s sense of competence. Homework tasks should be designed so that even young students can complete the task without adult help.

- Ownership — Tasks should be personally relevant and customised to promote ownership [viii] .

Academic purpose: all homework should clearly state the learning goal for the assignment. Sometimes homework tasks are well-intentioned attempts to have students do something fun or interesting, but the academic focus is not apparent (for instance, what exactly is the learning purpose of a word search?). Writing out definitions of vocabulary words or colouring in a map may sound like good homework, but one might question whether those tasks are appropriate to a focus on higher level thinking. Best practice suggests that students shouldn’t just write spelling words – they should use them to write declarative essays. They shouldn’t merely define the parts of the cell – they should create an analogy for the cell parts and functions. They shouldn’t just complete 20 identical math problems – they should apply math skills to new problems. Instead of reading logs which simply ask students (or parents) to document that they spent time reading, a better task would be to have the student write a reading blog to talk about what they have been reading.

Efficiency: sometraditional tasksmay be inefficient—either because they show no evidence of learning or because they take an inordinate amount of time. Projects that require non-academic skills (like cutting, gluing, or drawing) are often inefficient. Classic projects like dioramas, models, and poster displays are created by teachers with all the best intentions – they see them as a fun, creative way for students to show what they have learned. But unless content requirements are clearly spelled out in a rubric, projects can reveal very little about the student’s content knowledge and much more about their artistic talents.

Competence: an important objective of primary homework is to ensure that students feel positive about learning and develop an identity as successful learners. Homework tasks should be designed not only to support classroom learning but also to instill a sense of competence in the learner. In fact, when students feel unsuccessful in approaching homework tasks, they often avoid the tasks completely as a way to protect their self-esteem. Teachers should adjust homework difficulty or the amount of work based on their assessment of the student’s skill level or understanding. Struggling learners may need simpler reading material or tasks that are more concrete or more scaffolded. For students who work more slowly, the remedy should be to give the student less work rather than expecting them to work longer than other students. A simple differentiation for struggling learners is to make homework time-based (‘spend 20 minutes on this task, draw a line’) rather than task-based (finish the task regardless how long it takes). Just as checking for understanding is an important purpose for homework, teachers also need to check for frustration. Teachers should solicit feedback from students, finding out how students feel about approaching certain tasks and how they feel after they’ve attempted those tasks.

Ownership. Another important objective of homework is independent learning, but often homework is not structured with enough agency to allow for that independence. Perhaps that is because teachers believe the tasks they prescribe will naturally lead to the learning they desire for all students. But one-size-fits-all-homework rarely fits all. When we give students more ownership of the homework task, we make it more efficient and students are more motivated. Choice is at the heart of that student ownership. Homework choice can be as limited as ‘pick any 10 of the 30 problems’, as specific as having students work only on learning goals that they are struggling with, or as wide open as a self-selected and self-designed project. Students may not always have a choice about the learning goal, but they can almost always be given some agency in designing the best task for them to reach the goal. For instance, suppose the learning goal is for all students to memorise their multiplication tables. The homework might look like this:

- Create your own method to memorise your multiplication tables. Here are some ideas other students have tried – writing, reciting, making note cards, drawing a colour-coded chart, or creating a song.

- Share your idea with the class tomorrow.

- Practise your method this week.

- Evaluate how well your method worked after the quiz on Friday.

It may be helpful to think of the amount of ownership students are allowed in homework as a continuum from traditional to differentiated to personalised. Traditional homework is designed by teachers with no student input – prescribed tasks such as practice math problems or assigned reading in their science book. As we give students more ownership, we may give choices or we may differentiate. For instance, all students need to read, but they may be given choices of what they read. Students may need to practise subtraction, but they may create their own problems based on items in their home.

For the ultimate ownership, we may allow students to pursue personalised homework. Personalised homework involves students in goal setting (typically based on academic standards), planning a specific homework task, and planning how they will demonstrate learning. The personalised homework most familiar to teachers is probably genius hour (also called passion projects), which involves giving students a block of time to learn more about something that they are curious about, or that excites or inspires them. These long-term research projects often start in the classroom, with students transitioning to working on them as homework, bringing them back periodically for feedback, and eventually presenting their results to an audience.

What makes sense for many teachers is a balance of traditional homework, differentiated homework, and personalised homework over the course of a term or year. Often, some personalised homework will be blended into day-to-day learning in tandem with other more teacher-directed assignments. Many teachers reserve personalised homework for times when student motivation wanes, such as before the holidays or near the end of the school year.

Should homework be graded?

Research has shown the effect of feedback to be more powerful than many other factors that influence learning [ix] . As more primary schools focus on mastery learning, homework is increasingly viewed as formative feedback. The current consensus among researchers is that homework’s role should be as formative assessment—assessment for learning that takes place during learning [x] . Homework’s role is not assessment of learning – therefore, it should not be graded. Ideally, homework is given feedback, monitored for completion, and reported separately as a work habit.

Homework is just one part of an overall instructional plan. As our curricula, teaching strategies, and assessment strategies evolve to better meet student needs, so should our homework practices. Only by creating assignments that are effective and equitable can we make homework a valuable part of instruction and learning.

[i] Cooper, H. (2007). The battle over homework: Common ground for administrators, teachers, and parents. (3 rd edition). Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

[ii] Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (2014). Does homework perpetuate inequalities in education? www.oecd.org/pisa/pisa-2015-results-in-focus.pdf . Retrieved 8-4-17.

[iii] Horsley, M. and Walker, R. (2013). Reforming homework: practices, learning and policy. Melbourne, Victoria, Australia: Palgrave Macmillan.

[iv] Cooper, H. (2007). The battle over homework: Common ground for administrators, teachers, and parents. (3 rd edition). Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

[v] Vatterott, C. (2018). Rethinking homework: Best practices that support diverse needs , 2 nd edition. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development (ASCD).

[vi] Trautwein, U., & Koller, O. (2003). The relationship between homework and achievement—still much of a mystery. Educational Psychology Review, 15 (2), 115–145.

[vii] Vatterott, C. (2018). Rethinking homework: Best practices that support diverse needs , 2 nd edition. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development (ASCD).

[viii] Vatterott, C. (2010). Five hallmarks of good homework. Educational Leadership, 68(1), 10-15.

[ix] Hattie, J. (2009). Visible learning . London: Routledge.

[x] Vatterott, C. (2018). Rethinking homework: Best practices that support diverse needs , 2 nd edition. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development (ASCD).

By Dr Cathy Vatterott

PREPARED FOR THE EDUCATION HUB BY

Dr. Cathy Vatterott

Dr. Cathy Vatterott is Professor Emeritus of Education at the University of Missouri-St. Louis, and a former teacher and school principal. She is the author of four books, most recently Rethinking Homework: Best Practices That Support Diverse Needs, 2nd edition (ASCD, 2018), and Rethinking Grading: Meaningful Assessment for Standards Based Learning (ASCD, 2015). She frequently presents at national conferences and serves as a consultant and workshop presenter for K-12 schools on homework, grading practices, and teen stress. Dr. Vatterott has been researching, writing, and speaking about K-12 homework in the United States, Canada, and Europe for over 20 years and is considered an international expert on homework. She first became interested in homework in the late 1990s as the frustrated parent of a 5th grader with learning disabilities. Her work with schools has been the catalyst for her latest research on teen stress.

Download this resource as a PDF

Please provide your email address and confirm you are downloading this resource for individual use or for use within your school or ECE centre only, as per our Terms of Use . Other users should contact us to about for permission to use our resources.

Interested in * —Please choose an option— Early childhood education (ECE) Schools Both ECE and schools I agree to abide by The Education Hub's Terms of Use.

Did you find this article useful?

If you enjoyed this content, please consider making a charitable donation.

Become a supporter for as little as $1 a week – it only takes a minute and enables us to continue to provide research-informed content for teachers that is free, high-quality and independent.

Become a supporter

Get unlimited access to all our webinars

Buy a webinar subscription for your school or centre and enjoy savings of up to 25%, the education hub has changed the way it provides webinar content, to enable us to continue creating our high-quality content for teachers., an annual subscription of just nz$60 per person gives you access to all our live webinars for a whole year, plus the ability to watch any of the recordings in our archive. alternatively, you can buy access to individual webinars for just $9.95 each., we welcome group enrolments, and offer discounts of up to 25%. simply follow the instructions to indicate the size of your group, and we'll calculate the price for you. , unlimited annual subscription.

- All live webinars for 12 months

- Access to our archive of over 80 webinars

- Personalised certificates

- Group savings of up to 25%

The Education Hub’s mission is to bridge the gap between research and practice in education. We want to empower educators to find, use and share research to improve their teaching practice, and then share their innovations. We are building the online and offline infrastructure to support this to improve opportunities and outcomes for students. New Zealand registered charity number: CC54471

We’ll keep you updated

Click here to receive updates on new resources.

Interested in * —Please choose an option— Early childhood education (ECE) Schools Both ECE and schools

Follow us on social media

Like what we do please support us.

© The Education Hub 2024 All rights reserved | Site design: KOPARA

- Terms of use

- Privacy policy

Privacy Overview

Thanks for visiting our site. To show your support for the provision of high-quality research-informed resources for school teachers and early childhood educators, please take a moment to register.

Thanks, Nina

Should Kids Get Homework?

Homework gives elementary students a way to practice concepts, but too much can be harmful, experts say.

Getty Images

Effective homework reinforces math, reading, writing or spelling skills, but in a way that's meaningful.

How much homework students should get has long been a source of debate among parents and educators. In recent years, some districts have even implemented no-homework policies, as students juggle sports, music and other activities after school.

Parents of elementary school students, in particular, have argued that after-school hours should be spent with family or playing outside rather than completing assignments. And there is little research to show that homework improves academic achievement for elementary students.

But some experts say there's value in homework, even for younger students. When done well, it can help students practice core concepts and develop study habits and time management skills. The key to effective homework, they say, is keeping assignments related to classroom learning, and tailoring the amount by age: Many experts suggest no homework for kindergartners, and little to none in first and second grade.

Value of Homework

Homework provides a chance to solidify what is being taught in the classroom that day, week or unit. Practice matters, says Janine Bempechat, clinical professor at Boston University 's Wheelock College of Education & Human Development.

"There really is no other domain of human ability where anybody would say you don't need to practice," she adds. "We have children practicing piano and we have children going to sports practice several days a week after school. You name the domain of ability and practice is in there."

Homework is also the place where schools and families most frequently intersect.

"The children are bringing things from the school into the home," says Paula S. Fass, professor emerita of history at the University of California—Berkeley and the author of "The End of American Childhood." "Before the pandemic, (homework) was the only real sense that parents had to what was going on in schools."

Harris Cooper, professor emeritus of psychology and neuroscience at Duke University and author of "The Battle Over Homework," examined more than 60 research studies on homework between 1987 and 2003 and found that — when designed properly — homework can lead to greater student success. Too much, however, is harmful. And homework has a greater positive effect on students in secondary school (grades 7-12) than those in elementary.

"Every child should be doing homework, but the amount and type that they're doing should be appropriate for their developmental level," he says. "For teachers, it's a balancing act. Doing away with homework completely is not in the best interest of children and families. But overburdening families with homework is also not in the child's or a family's best interest."

Negative Homework Assignments

Not all homework for elementary students involves completing a worksheet. Assignments can be fun, says Cooper, like having students visit educational locations, keep statistics on their favorite sports teams, read for pleasure or even help their parents grocery shop. The point is to show students that activities done outside of school can relate to subjects learned in the classroom.

But assignments that are just busy work, that force students to learn new concepts at home, or that are overly time-consuming can be counterproductive, experts say.

Homework that's just busy work.

Effective homework reinforces math, reading, writing or spelling skills, but in a way that's meaningful, experts say. Assignments that look more like busy work – projects or worksheets that don't require teacher feedback and aren't related to topics learned in the classroom – can be frustrating for students and create burdens for families.

"The mental health piece has definitely played a role here over the last couple of years during the COVID-19 pandemic, and the last thing we want to do is frustrate students with busy work or homework that makes no sense," says Dave Steckler, principal of Red Trail Elementary School in Mandan, North Dakota.

Homework on material that kids haven't learned yet.

With the pressure to cover all topics on standardized tests and limited time during the school day, some teachers assign homework that has not yet been taught in the classroom.

Not only does this create stress, but it also causes equity challenges. Some parents speak languages other than English or work several jobs, and they aren't able to help teach their children new concepts.

" It just becomes agony for both parents and the kids to get through this worksheet, and the goal becomes getting to the bottom of (the) worksheet with answers filled in without any understanding of what any of it matters for," says professor Susan R. Goldman, co-director of the Learning Sciences Research Institute at the University of Illinois—Chicago .

Homework that's overly time-consuming.

The standard homework guideline recommended by the National Parent Teacher Association and the National Education Association is the "10-minute rule" – 10 minutes of nightly homework per grade level. A fourth grader, for instance, would receive a total of 40 minutes of homework per night.

But this does not always happen, especially since not every student learns the same. A 2015 study published in the American Journal of Family Therapy found that primary school children actually received three times the recommended amount of homework — and that family stress increased along with the homework load.

Young children can only remain attentive for short periods, so large amounts of homework, especially lengthy projects, can negatively affect students' views on school. Some individual long-term projects – like having to build a replica city, for example – typically become an assignment for parents rather than students, Fass says.

"It's one thing to assign a project like that in which several kids are working on it together," she adds. "In (that) case, the kids do normally work on it. It's another to send it home to the families, where it becomes a burden and doesn't really accomplish very much."

Private vs. Public Schools

Do private schools assign more homework than public schools? There's little research on the issue, but experts say private school parents may be more accepting of homework, seeing it as a sign of academic rigor.

Of course, not all private schools are the same – some focus on college preparation and traditional academics, while others stress alternative approaches to education.

"I think in the academically oriented private schools, there's more support for homework from parents," says Gerald K. LeTendre, chair of educational administration at Pennsylvania State University—University Park . "I don't know if there's any research to show there's more homework, but it's less of a contentious issue."

How to Address Homework Overload

First, assess if the workload takes as long as it appears. Sometimes children may start working on a homework assignment, wander away and come back later, Cooper says.

"Parents don't see it, but they know that their child has started doing their homework four hours ago and still not done it," he adds. "They don't see that there are those four hours where their child was doing lots of other things. So the homework assignment itself actually is not four hours long. It's the way the child is approaching it."

But if homework is becoming stressful or workload is excessive, experts suggest parents first approach the teacher, followed by a school administrator.

"Many times, we can solve a lot of issues by having conversations," Steckler says, including by "sitting down, talking about the amount of homework, and what's appropriate and not appropriate."

Study Tips for High School Students

Tags: K-12 education , students , elementary school , children

2024 Best Colleges

Search for your perfect fit with the U.S. News rankings of colleges and universities.

Creating a Homework Policy With Meaning and Purpose

- Tips & Strategies

- An Introduction to Teaching

- Policies & Discipline

- Community Involvement

- School Administration

- Technology in the Classroom

- Teaching Adult Learners

- Issues In Education

- Teaching Resources

- Becoming A Teacher

- Assessments & Tests

- Elementary Education

- Secondary Education

- Special Education

- Homeschooling

- M.Ed., Educational Administration, Northeastern State University

- B.Ed., Elementary Education, Oklahoma State University

We have all had time-consuming, monotonous, meaningless homework assigned to us at some point in our life. These assignments often lead to frustration and boredom and students learn virtually nothing from them. Teachers and schools must reevaluate how and why they assign homework to their students. Any assigned homework should have a purpose.

Assigning homework with a purpose means that through completing the assignment, the student will be able to obtain new knowledge, a new skill, or have a new experience that they may not otherwise have. Homework should not consist of a rudimentary task that is being assigned simply for the sake of assigning something. Homework should be meaningful. It should be viewed as an opportunity to allow students to make real-life connections to the content that they are learning in the classroom. It should be given only as an opportunity to help increase their content knowledge in an area.

Differentiate Learning for All Students

Furthermore, teachers can utilize homework as an opportunity to differentiate learning for all students. Homework should rarely be given with a blanket "one size fits all" approach. Homework provides teachers with a significant opportunity to meet each student where they are and truly extend learning. A teacher can give their higher-level students more challenging assignments while also filling gaps for those students who may have fallen behind. Teachers who use homework as an opportunity to differentiate we not only see increased growth in their students, but they will also find they have more time in class to dedicate to whole group instruction .

See Student Participation Increase

Creating authentic and differentiated homework assignments can take more time for teachers to put together. As often is the case, extra effort is rewarded. Teachers who assign meaningful, differentiated, connected homework assignments not only see student participation increase, they also see an increase in student engagement. These rewards are worth the extra investment in time needed to construct these types of assignments.

Schools must recognize the value in this approach. They should provide their teachers with professional development that gives them the tools to be successful in transitioning to assign homework that is differentiated with meaning and purpose. A school's homework policy should reflect this philosophy; ultimately guiding teachers to give their students reasonable, meaningful, purposeful homework assignments.

Sample School Homework Policy

Homework is defined as the time students spend outside the classroom in assigned learning activities. Anywhere Schools believes the purpose of homework should be to practice, reinforce, or apply acquired skills and knowledge. We also believe as research supports that moderate assignments completed and done well are more effective than lengthy or difficult ones done poorly.

Homework serves to develop regular study skills and the ability to complete assignments independently. Anywhere Schools further believes completing homework is the responsibility of the student, and as students mature they are more able to work independently. Therefore, parents play a supportive role in monitoring completion of assignments, encouraging students’ efforts and providing a conducive environment for learning.

Individualized Instruction

Homework is an opportunity for teachers to provide individualized instruction geared specifically to an individual student. Anywhere Schools embraces the idea that each student is different and as such, each student has their own individual needs. We see homework as an opportunity to tailor lessons specifically for an individual student meeting them where they are and bringing them to where we want them to be.

Homework contributes toward building responsibility, self-discipline, and lifelong learning habits. It is the intention of the Anywhere School staff to assign relevant, challenging, meaningful, and purposeful homework assignments that reinforce classroom learning objectives. Homework should provide students with the opportunity to apply and extend the information they have learned complete unfinished class assignments, and develop independence.

The actual time required to complete assignments will vary with each student’s study habits, academic skills, and selected course load. If your child is spending an inordinate amount of time doing homework, you should contact your child’s teachers.

- Homework Guidelines for Elementary and Middle School Teachers

- 6 Teaching Strategies to Differentiate Instruction

- Classroom Assessment Best Practices and Applications

- Essential Strategies to Help You Become an Outstanding Student

- An Overview of Renaissance Learning Programs

- Creating a Great Lesson to Maximize Student Learning

- Effective Classroom Policies and Procedures

- How Scaffolding Instruction Can Improve Comprehension

- The Whys and How-tos for Group Writing in All Content Areas

- How Much Homework Should Students Have?

- Gradual Release of Responsibility Creates Independent Learners

- 5 Types of Report Card Comments for Elementary Teachers

- Methods for Presenting Subject Matter

- 7 Reasons to Enroll Your Child in an Online Elementary School

- Teaching Strategies to Promote Student Equity and Engagement

- Collecting Homework in the Classroom

Homework tips for supporting children in primary school

Homework can be a sticking point for busy families.

After experts questioned its relevance for primary schoolers, many of you weighed in on Facebook, disagreeing on how much, if any, homework is the right amount for this age group.

So, what is beneficial? And what are some strategies to help make it a less stressful part of the day for both parents and kids?

What's the value in homework?

Grattan Institute deputy program director Amy Haywood says there is value in homework — particularly set reading — for primary school-aged kids.

Ms Haywood, based in Naarm/Melbourne, says time spent reading independently or with an adult "is a really good use of time because it builds up the vocabulary".

In addition to reading, other key skills such as maths can be a focus.

"In classes is where they're doing a lot of the learning of new content or skills, and then outside the school might be opportunity to practise."

She says there's "clear evidence around practice leading to mastery, and then the mastery having an impact on students' engagement in school, [and] their confidence with taking on different learning tasks".

There's also a case for homework in later primary years as you might want them to build some of those study habits before they go into secondary school.

But, she says "schools need to be careful about what homework they are setting".

Communicate with the school

Ms Haywood encourages parents to speak to teachers if they have concerns about set homework.

"[Teachers] may not necessarily realise that a student is spending a lot of time or needing quite a bit of help.

"That new information is very useful for a teacher because it means that they can go back and understand what they might need to reteach and any misconceptions that they need to go over."

Find the best time for your family

Parenting expert and family counsellor Rachel Schofield says finding the best time for homework in your family's routine is important.

Based in New South Wales' Bega Valley, on traditional lands of the Yuin-Monaro Nations, she says for some families fitting it into the morning routine is easier.

It's also about when parents and caregivers are in "the best shape" to help, "because if you've got a kid that's battling homework, you're going to have to be in emotionally good shape".

"If you're really stressed at the end of the day, then that's probably not the best time."

Ms Schofield says "parents have incredibly busy lives" but if you can carve out the time "homework can become a place where you actually get to slow down and stop".

She says children below the age of 10 need a lot a supervision and shouldn't be expected to do homework independently.

Why homework straight after school might not work

Ms Schofield says kids "need decompression time after school".

She says there's an understandable tendency among busy parents to get homework out of the way as soon as possible, but this could be working against them.

Snacks, play and time to offload are usually what primary-aged kids need, Ms Schofield says.

Some time to play and connect with a parent after school can be "really helpful".

Even 10 minutes "can make the whole trajectory of the evening go differently", she says.

Ms Schofield says kids can come home with "a lot of emotional stuff" and rough-and-tumble-play can be a good way to spend time with them and help them decompress after school.

Ms Schofield says you can also try and engage with your child 'playfully' if they are refusing to do homework.

It's tempting to be stern and serious in response, but she says treating it more "goofily" by poorly attempting to complete it yourself or asking your child for help with a task might get a better result.

ABC Everyday in your inbox

Get our newsletter for the best of ABC Everyday each week

- X (formerly Twitter)

Related Stories

Primary schools urged to have 'courage' to rethink homework if parents support the move.

Experts looked at 10,000 pieces of research to find the best way to learn to read – we've distilled it down for you

'Our two children's needs are entirely different': Parents' thoughts on banning social media for children

- Homework and Study

Primary school children get little academic benefit from homework

Lecturer and Researcher in Education, University of Hull

Disclosure statement

Paul Hopkins is a member of the Labour Party

University of Hull provides funding as a member of The Conversation UK.

View all partners

Homework: a word that can cause despair not just in children, but also in parents and even teachers. And for primary school children at least, it may be that schools setting homework is more trouble than it’s worth.

There is evidence that homework can be useful at secondary school . It can be used to consolidate material learnt in class or to prepare for exams.

However, it is less clear that homework is useful for children at primary school (ages 5 to 11) or in early years education (ages 3 to 5).

What is homework for?

There are no current guidelines on how much homework primary school children in England should be set. In 2018 then education secretary Damien Hinds stated that “We trust individual school head teachers to decide what their policy on homework will be, and what happens if pupils don’t do what’s set”.

While there is not much data available on how much homework primary school pupils do, a 2018 survey of around 1,000 parents found that primary pupils were spending an average of 2.2 hours per week on homework.

The homework done by primary school children can include reading, practising spellings, or revising for tests. Charity the Education Endowment Foundation suggests that the uses for homework at primary school include reinforcing the skills that pupils learn in school, helping them get ready for tests and preparing them for future school lessons.

Homework can also act as a point of communication between home and school, helping parents feel part of their child’s schooling.

However, the 2018 Ofsted Parents’ Panel – which surveyed the views of around 1,000 parents in England on educational issues – found that 36% of parents thought that homework was not helpful at all to their primary school children. The panel report found that, for many parents, homework was a significant source of stress and negatively affected family life.

Little academic benefit

Not much academic research has been carried out on the impact of homework for children in primary school. The available meta-studies – research that combines and analyses the findings of a number of studies – suggest that homework has little or no positive benefit for the academic achievement of children of primary school age . A central reason for this seems to be the inability of children to complete this homework without the support provided by teachers and the school.

Some research has suggested that primary pupils lack the independent study skills to do homework, and that they are not able to stay focused on the work.

What’s more, homework may actually have a negative effect if parents set unrealistic expectations, apply pressure or use methods that go counter to those used at school.

Homework may also increase inequalities between pupils. High achievers from economically privileged backgrounds may have greater parental support for homework, including more educated assistance, higher expectations and better settings and resources.

However, it is possible that setting homework for primary school children has benefits that cannot be easily measured, such as developing responsibility and independent problem-solving skills. It could also help children develop habits that will be useful in later school life.

A common task set for homework in primary schools is for children to read with their parents. There is some evidence that this has a positive impact as well as providing enjoyment, but the quality of interaction may be more important than the quantity.

If the purpose of homework is to develop the relationship between home and school and give parents more stake in the schooling of their children then this may well be a positive thing. If this is its purpose, though, it should not be used as a means to improve test scores or school performance metrics. For the youngest children, anything that takes time away from developmental play is a bad thing.

Rather, any homework should develop confidence and engagement in the process of schooling for both children and parents.

- Primary school

Head, School of Psychology

Senior Lecturer (ED) Ballarat

Senior Research Fellow - Women's Health Services

Lecturer / Senior Lecturer - Marketing

Assistant Editor - 1 year cadetship

Government agencies communicate via .gov.sg websites (e.g. go.gov.sg/open) . Trusted website s

Look for a lock ( ) or https:// as an added precaution. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

Homework Guidelines

Information for Parents

General Information

School Services and Fees

Assessments

Home Based Learning (HBL)

Student Learning Space (SLS)

e Newsletter

Parent Support Group

North Vista Primary Alumni

School Canteen

Homework refers to any learning activity that students are required to complete outside of curriculum time. This includes any extension of the classroom work, revision of school work, preparation of lessons, projects and online assignments.

The following table illustrates the guidelines for homework for the different levels:

Students are to take note of their homework by recording it down in their organizer daily.

To ensure that students benefit from the homework assigned, we would like to seek parents’ cooperation in the following areas:

- create a home environment conducive for studying and completion of homework;

- supervise and provide support for child’s learning;

- reinforce good study habits and attitudes;

- be mindful of the stresses arising from school homework and out-of-school activities, and help the child prioritize his/her time among these activities; and

- work in partnership with teachers to support child’s learning and development.

Headteacher-Trusted Tutoring

"This is one of the most effective interventions I have come across in my 27 years of teaching."

Free CPD and leadership support

All the latest guides, articles and news to help primary, secondary and trust leaders support your staff and pupils

The Great British Homework Debate 2024 – Is It Necessary At Primary School?

Alexander Athienitis

The homework debate is never much out of the news. Should homework be banned? Is homework at primary school a waste of time? Do our children get too much homework?

Not long ago, UK-based US comedian Rob Delaney set the world alight with a tweet giving his own personal view of homework at primary school. We thought, as an organisation that provides maths homework support on a weekly basis, it was time to look at the facts around the homework debate in primary schools as well as, of course, reflecting the views of celebrities and those perhaps more qualified to offer an opinion!

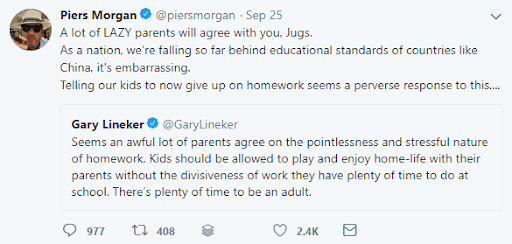

Here’s how Rob Delaney kicked things off

Gary Lineker leant his support with the following soundbite:

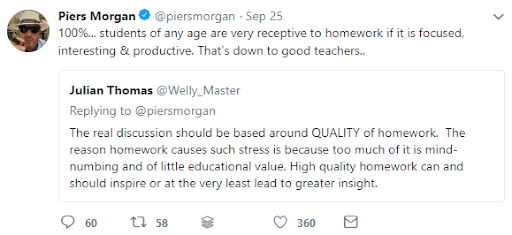

And even Piers Morgan weighed in, with his usual balance of tact and sensitivity:

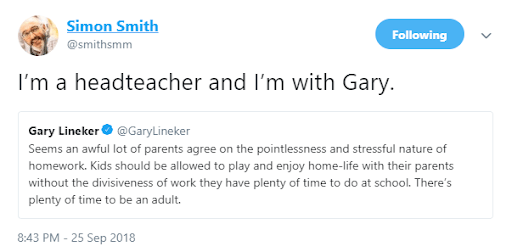

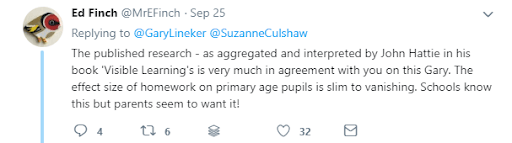

A very experienced and knowledgeable Headteacher, Simon Smith, who has a well-earned following on Twitter (for someone working in education, not hosting Match of the Day) also put his neck on the line and, some might think controversially, agreed with the golden-heeled Crisp King of Leicester…

Fortunately Katharine Birbalsingh, Conservative Party Conference keynote speaker and Founding Headteacher of the Michaela School, was on hand to provide the alternative view on the importance of homework. Her op-ed piece in the Sun gave plenty of reasons why homework should not be banned.

She was informative and firm in her article stating: “Homework is essential for a child’s education because revisiting the day’s learning is what helps to make it stick.”

KS2 Maths Games and Activities Pack

A FREE downloadable games and activity pack, including 20 home learning maths activities for KS2 children. Bring maths into your home in a fun way.

How much homework do UK primary school children get?

Sadly, there’s little data comparing how much homework primary school-aged children in the UK and across the globe complete on a weekly basis. A study of teenagers used by The Telegraph shows that American high-schoolers spend an average of 6.1 hours per week compared with 4.9 hours per week of homework each week for UK-based teens.

Up until 2012, the Department of Education recommended an hour of homework a week for primary school Key Stage 1 children (aged 4 to 7) and half an hour a day for primary school Key Stage 2 children (aged 7-11). Many primary schools still use this as a guideline.

Teachers, parents and children in many schools across the land have seen more changes of homework policy than numbers of terms in some school years.

A ‘no-homework’ policy pleases only a few; a grid of creative tasks crowd-sourced from the three teachers bothered to give their input infuriates many (parents, teachers and children alike). For some parents, no matter how much homework is set, it’s never enough; for others, even asking them to fill in their child’s reading record once a week can be a struggle due to a busy working life.

Homework is very different around the world

We’d suggest that Piers Morgan’s argument for homework in comparing the UK’s economic and social progress with China’s in recent years based on total weekly homework hours is somewhat misguided – we can’t put their emergence as the world’s (if not already, soon to be) leading superpower exclusively down to having their young people endure almost triple the number of hours spent completing homework as their Western counterparts.

Nonetheless, there’s certainly a finer balance to strike between the 14 hours a week suffered by Shanghainese school-attendees and none whatsoever. Certainly parents in the UK spend less time each week helping their children than parents in emerging economies such as India, Vietnam and Colombia (Source: Varkey Foundation Report).

Disadvantages of homework at primary school

Delaney, whose son attends a London state primary school, has made it plain that he thinks his kids get given too much homework and he’d rather have them following more active or creative pursuits: drawing or playing football. A father of four sons and a retired professional footballer Gary Linaker was quick to defend this but he also has the resources to send his children to top boarding schools which generally provide very structured homework or ‘prep’ routines.

As parents Rob and Gary are not alone. According to the 2018 Ofsted annual report on Parents Views more than a third of parents do not think homework in primary school is helpful to their children. They cite the battles and arguments it causes not to mention the specific challenges it presents to families with SEND children many of whom report serious damage to health and self-esteem as a result of too much or inappropriate homework.

It’s a truism among teachers that some types of homework tells you very little about what the child can achieve and much more about a parent’s own approach to the work. How low does your heart sink when your child comes back with a D & T project to create Stonehenge and you realise it’s either an all-nighter with glue, cardboard and crayons for you, or an uncompleted homework project for your child!

Speaking with our teacher hats on, we can tell you that homework is often cited in academic studies looking at academic progress in primary school-aged children as showing minimal to no impact.

Back on Twitter, a fellow teacher was able to weigh-in with that point:

Benefits of homework at primary school

So what are the benefits of homework at primary school? According to the Education Endowment Foundation (EEF) (the key research organisations dedicated to breaking the link between family income and educational achievement) the impact of homework at primary is low, but it also doesn’t cost much.

They put it at a “+2 months” impact against a control of doing nothing. To put this into context, 1-to-1 tuition is generally seen as a +5 months impact but it’s usually considered to be expensive.

“There is some evidence that when homework is used as a short and focused intervention it can be effective in improving students’ attainment … overall the general benefits are likely to be modest if homework is more routinely set.”

Key to the benefit you’ll see from homework is that the task is appropriate and of good quality. The quantity of homework a pupil does is not so important. In this matter Katharine Birbalsingh is on the money. Short focused tasks which relate directly to what is being taught, and which are built upon in school, are likely to be more effective than regular daily homework.

In our view it’s about consolidation. So focusing on a few times tables that you find tricky or working through questions similar to what you’ve done in class that day or week often can be beneficial. 2 hours of worksheets on a Saturday when your child could be outside having fun and making friends probably isn’t. If you really want them to be doing maths, then do some outdoor maths with them instead of homework !

At Third Space Learning we believe it’s all about balance. Give the right sort of homework and the right amount at primary school and there will be improvements, but much of it comes down to parental engagement.

One of our favourite ways to practise maths at home without it become too onerous is by using educational games. Here are our favourite fun maths games , some brilliant KS2 maths games , KS1 maths games and KS3 maths games for all maths topics and then a set of 35 times tables games which are ideal for interspersing with your regular times tables practice. And best of all, most of them require no more equipment than a pen and paper or perhaps a pack of cards.

Homework and parents