- Business Essentials

- Leadership & Management

- Credential of Leadership, Impact, and Management in Business (CLIMB)

- Entrepreneurship & Innovation

- Digital Transformation

- Finance & Accounting

- Business in Society

- For Organizations

- Support Portal

- Media Coverage

- Founding Donors

- Leadership Team

- Harvard Business School →

- HBS Online →

- Business Insights →

Business Insights

Harvard Business School Online's Business Insights Blog provides the career insights you need to achieve your goals and gain confidence in your business skills.

- Career Development

- Communication

- Decision-Making

- Earning Your MBA

- Negotiation

- News & Events

- Productivity

- Staff Spotlight

- Student Profiles

- Work-Life Balance

- AI Essentials for Business

- Alternative Investments

- Business Analytics

- Business Strategy

- Business and Climate Change

- Creating Brand Value

- Design Thinking and Innovation

- Digital Marketing Strategy

- Disruptive Strategy

- Economics for Managers

- Entrepreneurship Essentials

- Financial Accounting

- Global Business

- Launching Tech Ventures

- Leadership Principles

- Leadership, Ethics, and Corporate Accountability

- Leading Change and Organizational Renewal

- Leading with Finance

- Management Essentials

- Negotiation Mastery

- Organizational Leadership

- Power and Influence for Positive Impact

- Strategy Execution

- Sustainable Business Strategy

- Sustainable Investing

- Winning with Digital Platforms

What Is Creative Problem-Solving & Why Is It Important?

- 01 Feb 2022

One of the biggest hindrances to innovation is complacency—it can be more comfortable to do what you know than venture into the unknown. Business leaders can overcome this barrier by mobilizing creative team members and providing space to innovate.

There are several tools you can use to encourage creativity in the workplace. Creative problem-solving is one of them, which facilitates the development of innovative solutions to difficult problems.

Here’s an overview of creative problem-solving and why it’s important in business.

Access your free e-book today.

What Is Creative Problem-Solving?

Research is necessary when solving a problem. But there are situations where a problem’s specific cause is difficult to pinpoint. This can occur when there’s not enough time to narrow down the problem’s source or there are differing opinions about its root cause.

In such cases, you can use creative problem-solving , which allows you to explore potential solutions regardless of whether a problem has been defined.

Creative problem-solving is less structured than other innovation processes and encourages exploring open-ended solutions. It also focuses on developing new perspectives and fostering creativity in the workplace . Its benefits include:

- Finding creative solutions to complex problems : User research can insufficiently illustrate a situation’s complexity. While other innovation processes rely on this information, creative problem-solving can yield solutions without it.

- Adapting to change : Business is constantly changing, and business leaders need to adapt. Creative problem-solving helps overcome unforeseen challenges and find solutions to unconventional problems.

- Fueling innovation and growth : In addition to solutions, creative problem-solving can spark innovative ideas that drive company growth. These ideas can lead to new product lines, services, or a modified operations structure that improves efficiency.

Creative problem-solving is traditionally based on the following key principles :

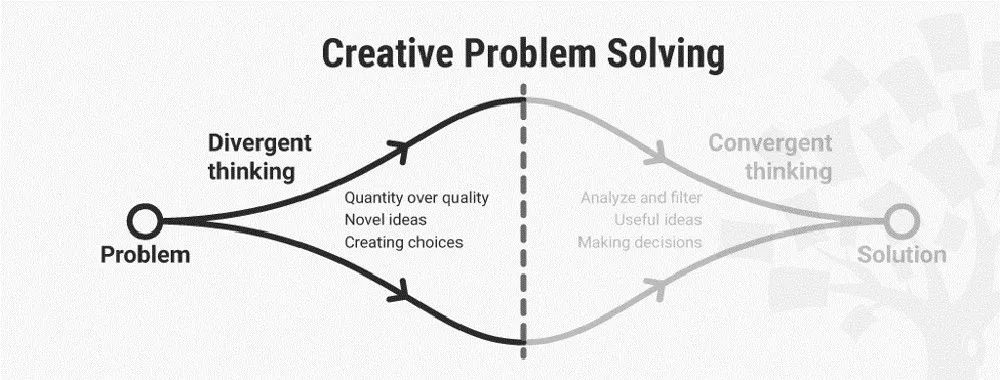

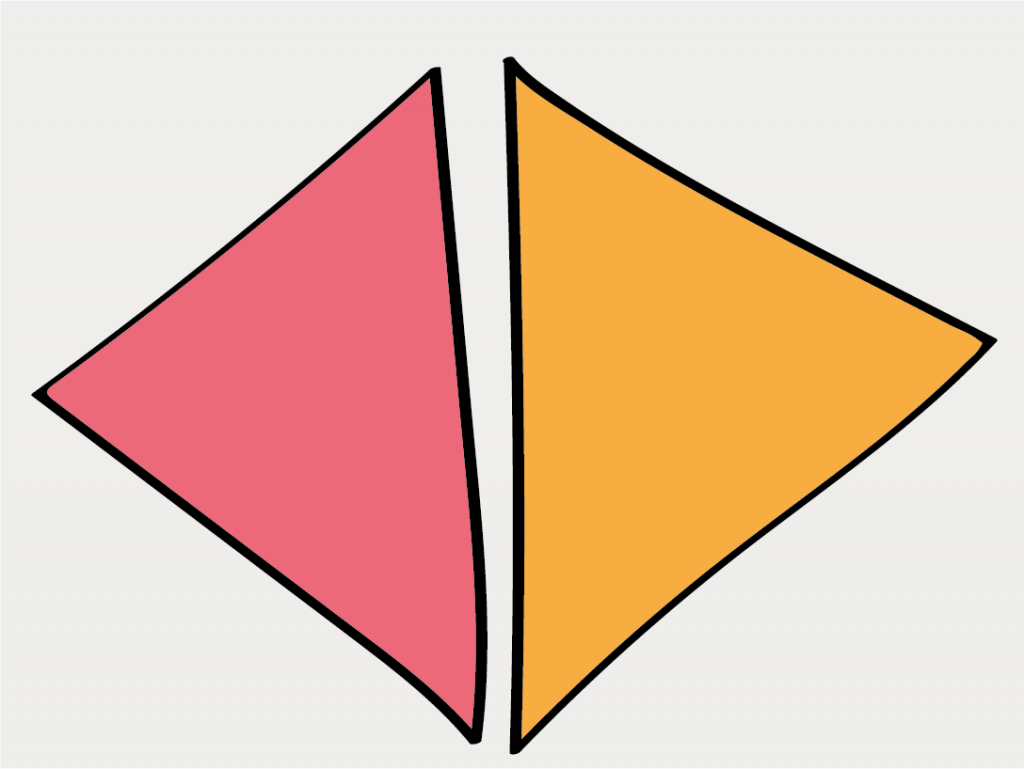

1. Balance Divergent and Convergent Thinking

Creative problem-solving uses two primary tools to find solutions: divergence and convergence. Divergence generates ideas in response to a problem, while convergence narrows them down to a shortlist. It balances these two practices and turns ideas into concrete solutions.

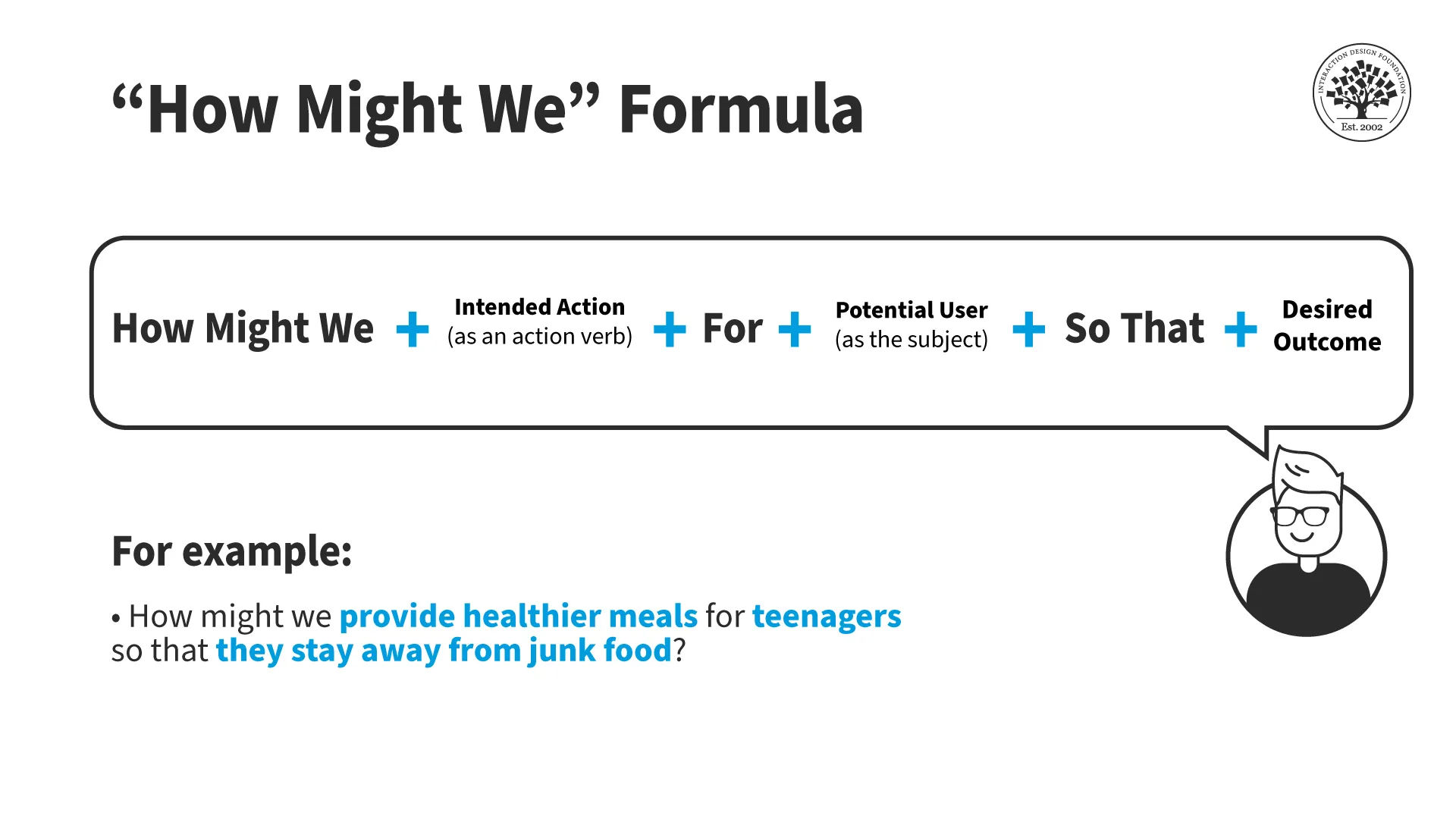

2. Reframe Problems as Questions

By framing problems as questions, you shift from focusing on obstacles to solutions. This provides the freedom to brainstorm potential ideas.

3. Defer Judgment of Ideas

When brainstorming, it can be natural to reject or accept ideas right away. Yet, immediate judgments interfere with the idea generation process. Even ideas that seem implausible can turn into outstanding innovations upon further exploration and development.

4. Focus on "Yes, And" Instead of "No, But"

Using negative words like "no" discourages creative thinking. Instead, use positive language to build and maintain an environment that fosters the development of creative and innovative ideas.

Creative Problem-Solving and Design Thinking

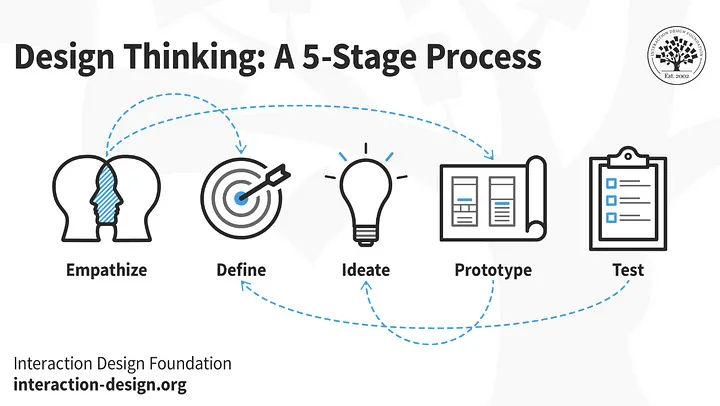

Whereas creative problem-solving facilitates developing innovative ideas through a less structured workflow, design thinking takes a far more organized approach.

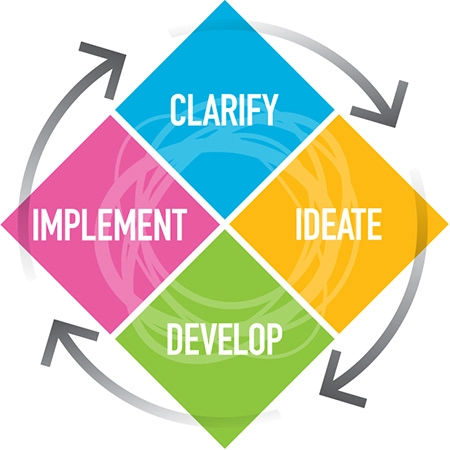

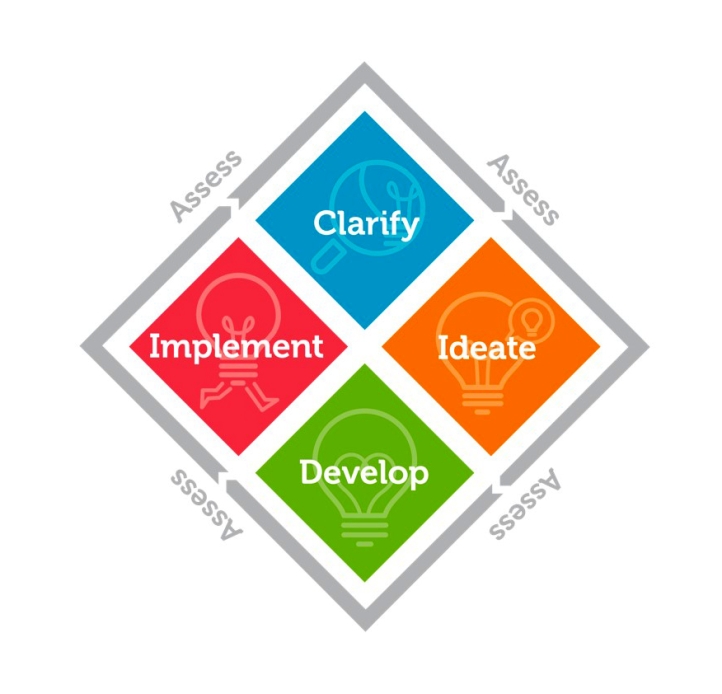

Design thinking is a human-centered, solutions-based process that fosters the ideation and development of solutions. In the online course Design Thinking and Innovation , Harvard Business School Dean Srikant Datar leverages a four-phase framework to explain design thinking.

The four stages are:

- Clarify: The clarification stage allows you to empathize with the user and identify problems. Observations and insights are informed by thorough research. Findings are then reframed as problem statements or questions.

- Ideate: Ideation is the process of coming up with innovative ideas. The divergence of ideas involved with creative problem-solving is a major focus.

- Develop: In the development stage, ideas evolve into experiments and tests. Ideas converge and are explored through prototyping and open critique.

- Implement: Implementation involves continuing to test and experiment to refine the solution and encourage its adoption.

Creative problem-solving primarily operates in the ideate phase of design thinking but can be applied to others. This is because design thinking is an iterative process that moves between the stages as ideas are generated and pursued. This is normal and encouraged, as innovation requires exploring multiple ideas.

Creative Problem-Solving Tools

While there are many useful tools in the creative problem-solving process, here are three you should know:

Creating a Problem Story

One way to innovate is by creating a story about a problem to understand how it affects users and what solutions best fit their needs. Here are the steps you need to take to use this tool properly.

1. Identify a UDP

Create a problem story to identify the undesired phenomena (UDP). For example, consider a company that produces printers that overheat. In this case, the UDP is "our printers overheat."

2. Move Forward in Time

To move forward in time, ask: “Why is this a problem?” For example, minor damage could be one result of the machines overheating. In more extreme cases, printers may catch fire. Don't be afraid to create multiple problem stories if you think of more than one UDP.

3. Move Backward in Time

To move backward in time, ask: “What caused this UDP?” If you can't identify the root problem, think about what typically causes the UDP to occur. For the overheating printers, overuse could be a cause.

Following the three-step framework above helps illustrate a clear problem story:

- The printer is overused.

- The printer overheats.

- The printer breaks down.

You can extend the problem story in either direction if you think of additional cause-and-effect relationships.

4. Break the Chains

By this point, you’ll have multiple UDP storylines. Take two that are similar and focus on breaking the chains connecting them. This can be accomplished through inversion or neutralization.

- Inversion: Inversion changes the relationship between two UDPs so the cause is the same but the effect is the opposite. For example, if the UDP is "the more X happens, the more likely Y is to happen," inversion changes the equation to "the more X happens, the less likely Y is to happen." Using the printer example, inversion would consider: "What if the more a printer is used, the less likely it’s going to overheat?" Innovation requires an open mind. Just because a solution initially seems unlikely doesn't mean it can't be pursued further or spark additional ideas.

- Neutralization: Neutralization completely eliminates the cause-and-effect relationship between X and Y. This changes the above equation to "the more or less X happens has no effect on Y." In the case of the printers, neutralization would rephrase the relationship to "the more or less a printer is used has no effect on whether it overheats."

Even if creating a problem story doesn't provide a solution, it can offer useful context to users’ problems and additional ideas to be explored. Given that divergence is one of the fundamental practices of creative problem-solving, it’s a good idea to incorporate it into each tool you use.

Brainstorming

Brainstorming is a tool that can be highly effective when guided by the iterative qualities of the design thinking process. It involves openly discussing and debating ideas and topics in a group setting. This facilitates idea generation and exploration as different team members consider the same concept from multiple perspectives.

Hosting brainstorming sessions can result in problems, such as groupthink or social loafing. To combat this, leverage a three-step brainstorming method involving divergence and convergence :

- Have each group member come up with as many ideas as possible and write them down to ensure the brainstorming session is productive.

- Continue the divergence of ideas by collectively sharing and exploring each idea as a group. The goal is to create a setting where new ideas are inspired by open discussion.

- Begin the convergence of ideas by narrowing them down to a few explorable options. There’s no "right number of ideas." Don't be afraid to consider exploring all of them, as long as you have the resources to do so.

Alternate Worlds

The alternate worlds tool is an empathetic approach to creative problem-solving. It encourages you to consider how someone in another world would approach your situation.

For example, if you’re concerned that the printers you produce overheat and catch fire, consider how a different industry would approach the problem. How would an automotive expert solve it? How would a firefighter?

Be creative as you consider and research alternate worlds. The purpose is not to nail down a solution right away but to continue the ideation process through diverging and exploring ideas.

Continue Developing Your Skills

Whether you’re an entrepreneur, marketer, or business leader, learning the ropes of design thinking can be an effective way to build your skills and foster creativity and innovation in any setting.

If you're ready to develop your design thinking and creative problem-solving skills, explore Design Thinking and Innovation , one of our online entrepreneurship and innovation courses. If you aren't sure which course is the right fit, download our free course flowchart to determine which best aligns with your goals.

About the Author

What is Integrative Thinking? A Key to Creative Problem-Solving

In the realm of navigating complex problems and making decisions that stand out with innovation and creativity, there exists a formidable tool – integrative thinking.

This article invites you to delve into the profound world of integrative thinking, where we will uncover its essence, explore the common obstacles that can obstruct its path, illuminate the remarkable benefits it bestows, and guide you on the journey to nurture and master this indispensable skill.

Join us on this transformative expedition as we unravel the potential of integrative thinking, forever altering the way you confront intricate challenges.

What is Integrative Thinking?

Integrative thinking transcends the label of a mere problem-solving technique; it embodies a cognitive approach that plunges into the realm of intellectual synthesis.

At its core, it involves the art of harmonizing ideas and concepts that may initially appear opposing or even contradictory.

The ultimate goal?

Crafting a solution that stands as a testament to innovation and originality. This approach liberates us from the constraints of binary choices, celebrating the rich tapestry of paradox.

Common Obstacles to Integrative Thinking

Rigid thinking .

One of the primary obstacles to integrative thinking is a rigid mindset .

When individuals adhere stubbornly to familiar solutions and established patterns of thought, it can hinder the creative process.

To truly embrace integrative thinking, it’s crucial to break free from the confines of rigid mental frameworks and be open to exploring new ideas and alternative approaches.

Fear of ambiguity

A prevalent hurdle that often arises is the discomfort with ambiguity and uncertainty.

It’s human nature to seek clear-cut, definitive solutions, shying away from the enigmatic territories of ambiguity.

However, integrative thinkers willingly wade into these nebulous waters, unafraid of the complexities that they hold.

They understand that within the realms of ambiguity lie fertile grounds for the birth of creative synthesis and the emergence of innovative solutions .

Time pressure

The demand for integrative thinking can sometimes clash with the swift pace of decision-making in many scenarios.

Integrative thinking thrives on the luxury of time and deep reflection, qualities that may seem at odds with the hurried nature of modern decision-making.

When faced with time pressure, individuals often gravitate towards quick, binary choices, leaving behind the nuanced exploration required for integrative thinking.

Tackling this challenge may entail creating environments conducive to thoughtful consideration or finding innovative ways to prioritize the integrative thinking process, even within the confines of time constraints.

Benefits of Integrative Thinking

Creative problem-solving .

Integrative thinkers possess remarkable skills for delving into the realm of creative problem-solving.

They excel at crafting solutions that transcend the boundaries of conventional thinking, breaking free from the shackles of established norms and restrictions.

With a keen ability to synthesize diverse and even opposing ideas, integrative thinkers breathe life into innovative solutions that breathe fresh air into the world of problem-solving.

Enhanced decision-making

The integrative thinking approach casts a wide net, encompassing a broader range of factors and perspectives.

This holistic consideration leads to decisions that are not only more informed but also inherently robust.

When faced with complex choices, integrative thinkers have the capacity to navigate the intricate web of possibilities, resulting in decisions that stand the test of scrutiny and time.

Conflict resolution

In the turbulent waters of conflicting viewpoints and opposing stances, integrative thinking emerges as a potent tool for resolution.

Its ability to harmonize seemingly irreconcilable differences and uncover common ground makes it invaluable in situations fraught with conflict.

Integrative thinkers act as mediators, weaving together the threads of disparate ideas to create a tapestry of understanding and consensus.

Improved leadership

Beyond its immediate problem-solving applications, integrative thinking also bestows upon individuals enhanced leadership capabilities.

In a world marked by rapid change and uncertainty, adaptability and visionary thinking are essential qualities for effective leadership .

Integrative thinking nurtures these attributes, equipping leaders with the agility and foresight needed to navigate the ever-evolving landscapes of their domains.

How to Develop Integrative Thinking Skills

Diverse perspectives .

At the core of integrative thinking lies a fundamental principle – the eagerness to explore diverse perspectives and engage with a multitude of opinions.

It’s a proactive endeavor that involves connecting with individuals hailing from diverse backgrounds, disciplines, and life journeys.

This deliberate act serves as a conduit to expand the horizons of your thinking, ushering in a rich mosaic of ideas and experiences that breathe depth and creativity into your problem-solving journey.

Question assumptions

Integrative thinkers possess a remarkable skill – the ability to systematically challenge their assumptions and preconceived notions.

They embrace a mindset that is in a constant state of inquiry, forever echoing the question, “What if things don’t have to be this way?”.

This persistent probing question serves as a potent catalyst for liberating their thoughts from the shackles of conventional wisdom.

It propels them into uncharted territories of thinking, where innovation thrives, and the exploration of alternative paths is not just encouraged but passionately pursued.

Practice mindfulness

Nurturing mindfulness and self-awareness stands as a crucial pillar of integrative thinking.

It’s a practice that beckons individuals to keep their minds open to the influx of new ideas, resist the allure of knee-jerk reactions, and embrace the ever-precious present moment.

Mindfulness becomes the guiding light that allows individuals to take a step back from automated responses, offering them the opportunity to delve deeper into the intricate nuances of any given problem.

It’s a transformative practice that extends an invitation to clarity and a profound understanding of the multifaceted complexities that define the challenges we face.

Scenario planning

Integrative thinkers excel at considering multiple scenarios and potential outcomes before making decisions.

They engage in scenario planning, meticulously exploring various paths that may unfold in response to their choices.

This forward-thinking approach equips them with the foresight needed to make robust and resilient decisions in an ever-changing world.

Collaboration

Collaboration is at the heart of integrative thinking.

Recognizing the power of collective wisdom and diverse viewpoints, integrative thinkers actively seek out collaboration with others.

They understand that the fusion of ideas generated through collaborative efforts can lead to groundbreaking solutions that transcend individual capabilities.

Integrative thinking isn’t just a cognitive skill; it’s a mindset that fuels innovation and sparks creativity.

When you open yourself to complexity and actively strive to unite conflicting ideas, you unlock the potential of integrative thinking.

It becomes a powerful tool for confronting challenges head-on, making well-informed decisions, and confidently navigating the intricate landscape of the contemporary world.

While both involve cognitive processes, integrative thinking focuses on synthesizing opposing ideas, whereas critical thinking involves analyzing and evaluating information.

Yes, integrative thinking is a skill that can be cultivated through practice and a willingness to explore diverse perspectives.

Integrative thinking is valuable across various fields, including business, science, politics, and the arts. It’s especially beneficial in situations requiring creative problem-solving and innovation.

The Evolution of Writing Tools: Who Invented The First Pen

Unraveling the Origins: How Do Personality Disorders Develop

Username or Email Address

Remember Me

Forgot password?

Enter your account data and we will send you a link to reset your password.

Your password reset link appears to be invalid or expired.

Privacy policy.

To use social login you have to agree with the storage and handling of your data by this website. %privacy_policy%

Add to Collection

Public collection title

Private collection title

No Collections

Here you'll find all collections you've created before.

Hey Friend! Before You Go…

Get the best viral stories straight into your inbox before everyone else!

Email address:

Don't worry, we don't spam

- Reviews / Why join our community?

- For companies

- Frequently asked questions

Creative Problem Solving

What is creative problem solving.

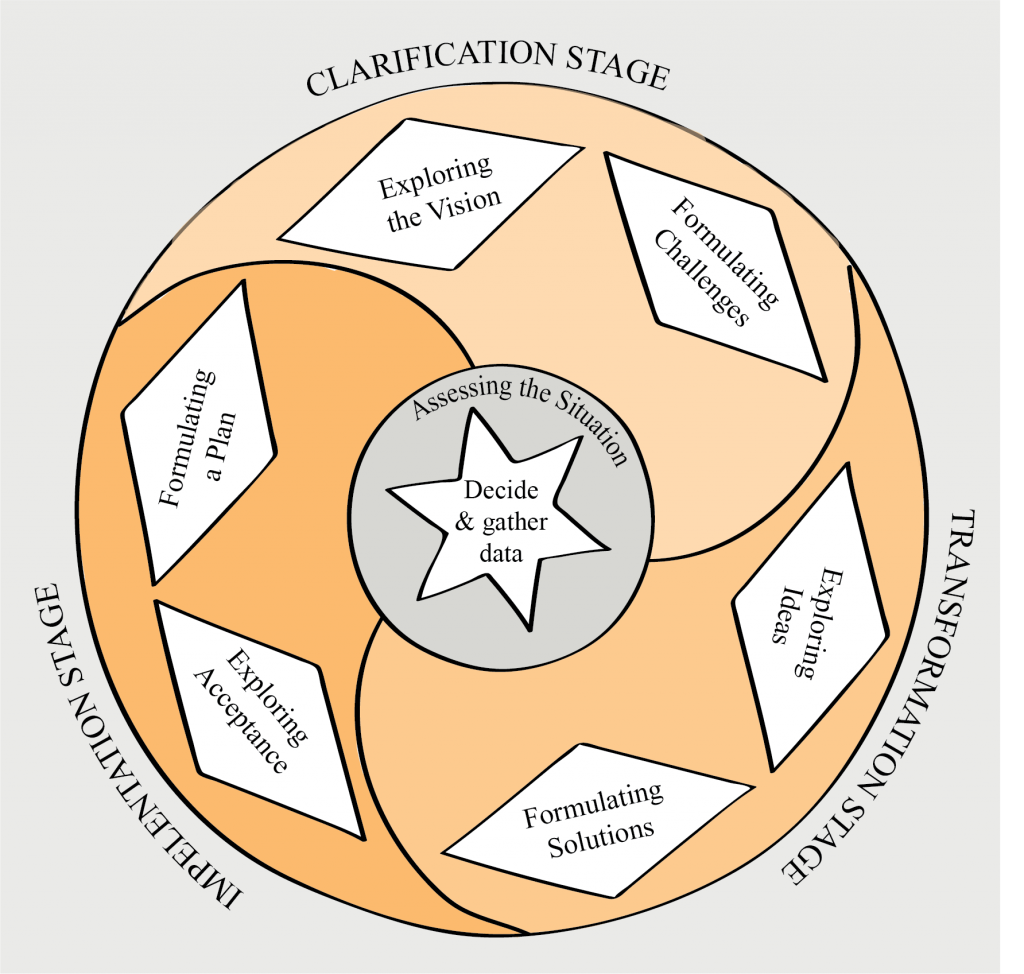

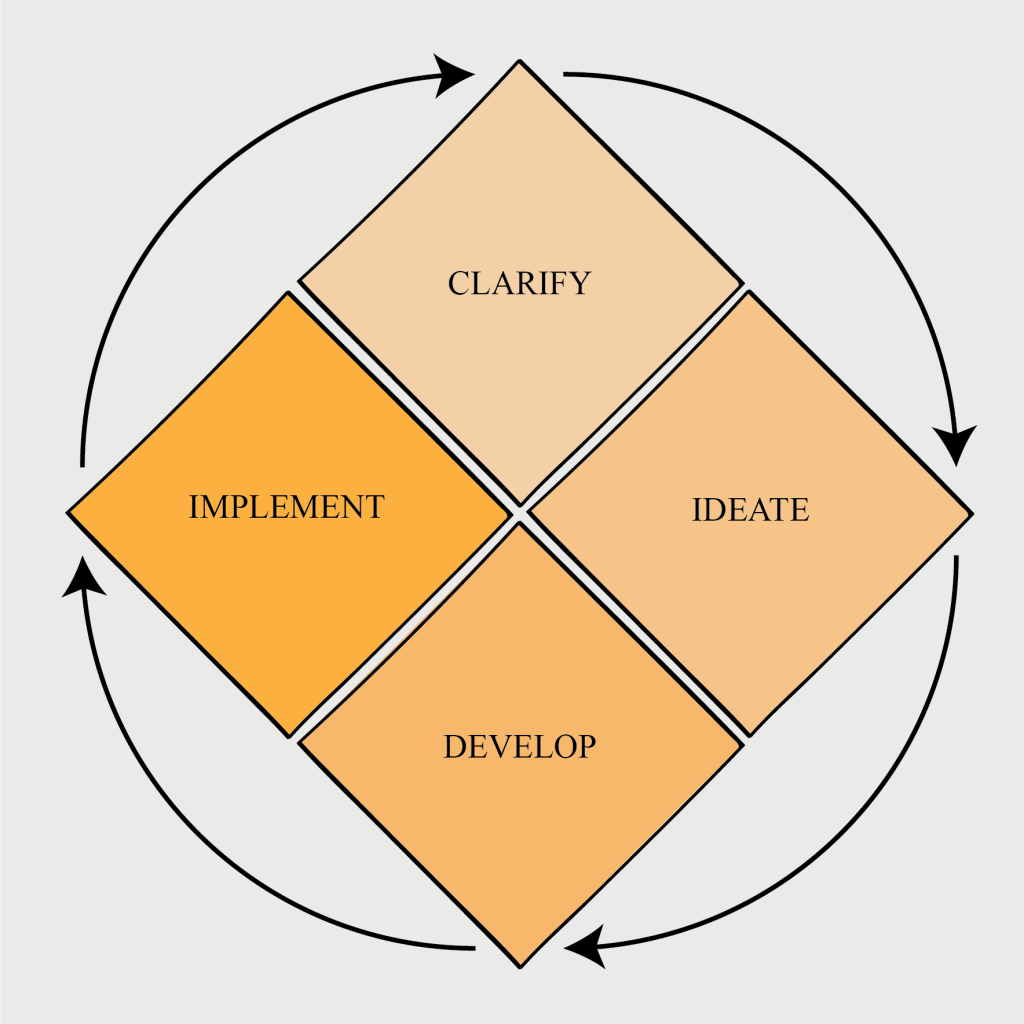

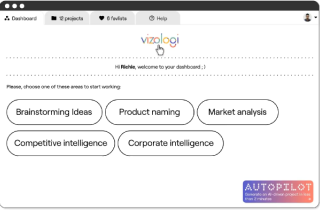

Creative problem solving (CPS) is a process that design teams use to generate ideas and solutions in their work. Designers and design teams apply an approach where they clarify a problem to understand it, ideate to generate good solutions, develop the most promising one, and implement it to create a successful solution for their brand’s users.

© Creative Education Foundation, Fair Use

Why is Creative Problem Solving in UX Design Important?

Creative thinking and problem solving are core parts of user experience (UX) design. Note: the abbreviation “CPS” can also refer to cyber-physical systems. Creative problem solving might sound somewhat generic or broad. However, it’s an ideation approach that’s extremely useful across many industries.

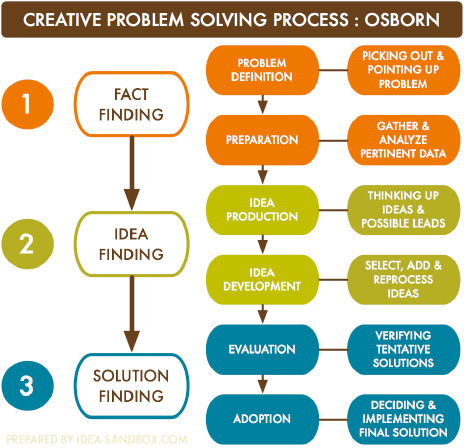

Not strictly a UX design-related approach, creative problem solving has its roots in psychology and education. Alex Osborn—who founded the Creative Education Foundation and devised brainstorming techniques—produced this approach to creative thinking in the 1940s. Along with Sid Parnes, he developed the Osborn-Parnes Creative Problem Solving Process. It was a new, systematic approach to problem solving and creativity fostering.

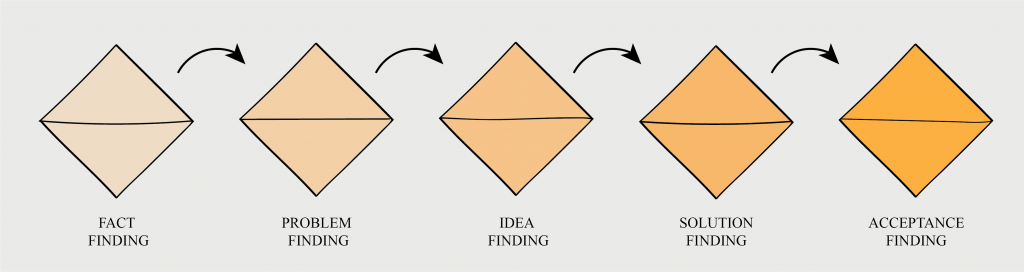

Osborn’s CPS Process.

© IdeaSandbox.com, Fair Use

The main focus of the creative problem solving model is to improve creative thinking and generate novel solutions to problems. An important distinction exists between it and a UX design process such as design thinking. It’s that designers consider user needs in creative problem solving techniques, but they don’t necessarily have to make their users’ needs the primary focus. For example, a design team might trigger totally novel ideas from random stimuli—as opposed to working systematically from the initial stages of empathizing with their users. Even so, creative problem solving methods still tend to follow a process with structured stages.

What are 4 Stages of Creative Problem Solving?

The model, adapted from Osborn’s original, typically features these steps:

Clarify: Design teams first explore the area they want to find a solution within. They work to spot the challenge, problem or even goal they want to identify. They also start to collect data or information about it. It’s vital to understand the exact nature of the problem at this stage. So, design teams must build a clear picture of the issue they seek to tackle creatively. When they define the problem like this, they can start to question it with potential solutions.

Ideate: Now that the team has a grasp of the problem that faces them, they can start to work to come up with potential solutions. They think divergently in brainstorming sessions and other ways to solve problems creatively, and approach the problem from as many angles as they can.

Develop: Once the team has explored the potential solutions, they evaluate these and find the strongest and weakest qualities in each. Then, they commit to the one they decide is the best option for the problem at hand.

Implement: Once the team has decided on the best fit for what they want to use, they discuss how to put this solution into action. They gauge its acceptability for stakeholders. Plus, they develop an accurate understanding of the activities and resources necessary to see it become a real, bankable solution.

What Else does CPS Involve?

© Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 4.0

Two keys to the enterprise of creative problem solving are:

Divergent Thinking

This is an ideation mode which designers leverage to widen their design space when they start to search for potential solutions. They generate as many new ideas as possible using various methods. For example, team members might use brainstorming or bad ideas to explore the vast area of possibilities. To think divergently means to go for:

Quantity over quality: Teams generate ideas without fear of judgment (critically evaluating these ideas comes later).

Novel ideas: Teams use disruptive and lateral thinking to break away from linear thinking and strive for truly original and extraordinary ideas.

Choice creation: The freedom to explore the design space helps teams maximize their options, not only regarding potential solutions but also about how they understand the problem itself.

Author and Human-Computer Interactivity Expert, Professor Alan Dix explains some techniques that are helpful for divergent thinking:

- Transcript loading…

Convergent Thinking

This is the complementary half of the equation. In this ideation mode, designers analyze, filter, evaluate, clarify and modify the ideas they generated during divergent thinking. They use analytical, vertical and linear thinking to isolate novel and useful ideas, understand the design space possibilities and get nearer to potential solutions that will work best. The purpose with convergent thinking is to carefully and creatively:

Look past logical norms (which people use in everyday critical thinking).

Examine how an idea stands in relation to the problem.

Understand the real dimensions of that problem.

Professor Alan Dix explains convergent thinking in this video:

What are the Benefits of Creative Problem Solving?

Design teams especially can benefit from this creative approach to problem solving because it:

Empowers teams to arrive at a fine-grained definition of the problem they need to ideate over in a given situation.

Gives a structured, learnable way to conduct problem-solving activities and direct them towards the most fruitful outcomes.

Involves numerous techniques such as brainstorming and SCAMPER, so teams have more chances to explore the problem space more thoroughly.

Can lead to large numbers of possible solutions thanks to a dedicated balance of divergent and convergent thinking.

Values and nurtures designers and teams to create innovative design solutions in an accepting, respectful atmosphere.

Is a collaborative approach that enables multiple participants to contribute—which makes for a positive environment with buy-in from those who participate.

Enables teams to work out the most optimal solution available and examine all angles carefully before they put it into action.

Is applicable in various contexts—such as business, arts and education—as well as in many areas of life in general.

It’s especially crucial to see the value of creative problem solving in how it promotes out-of-the-box thinking as one of the valuable ingredients for teams to leverage.

Watch as Professor Alan Dix explains how to think outside the box:

How to Conduct Creative Problem Solving Best?

It’s important to point out that designers should consider—and stick to—some best practices when it comes to applying creative problem solving techniques. They should also adhere to some “house rules,” which the facilitator should define in no uncertain terms at the start of each session. So, designers and design teams should:

Define the chief goal of the problem-solving activity: Everyone involved should be on the same page regarding their objective and what they want to achieve, why it’s essential to do it and how it aligns with the values of the brand. For example, SWOT analysis can help with this. Clarity is vital in this early stage. Before team members can hope to work on ideating for potential solutions, they must recognize and clearly identify what the problem to tackle is.

Have access to accurate information: A design team must be up to date with the realities that their brand faces, realities that their users and customers face, as well as what’s going on in the industry and facts about their competitors. A team must work to determine what the desired outcome is, as well as what the stakeholders’ needs and wants are. Another factor to consider in detail is what the benefits and risks of addressing a scenario or problem are—including the pros and cons that stakeholders and users would face if team members direct their attention on a particular area or problem.

Suspend judgment: This is particularly important for two main reasons. For one, participants can challenge assumptions that might be blocking healthy ideation when they suggest ideas or elements of ideas that would otherwise seem of little value through a “traditional” lens. Second, if everyone’s free to suggest ideas without constraints, it promotes a calmer environment of acceptance—and so team members will be more likely to ideate better. Judgment will come later, in convergent thinking when the team works to tighten the net around the most effective solution. So, everyone should keep to positive language and encourage improvisational tactics—such as “yes…and”—so ideas can develop well.

Balance divergent and convergent thinking: It’s important to know the difference between the two styles of thinking and when to practice them. This is why in a session like brainstorming, a facilitator must take control of proceedings and ensure the team engages in distinct divergent and convergent thinking sessions.

Approach problems as questions: For example, “How Might We” questions can prompt team members to generate a great deal of ideas. That’s because they’re open-ended—as opposed to questions with “yes” or “no” answers. When a team frames a problem so freely, it permits them to explore far into the problem space so they can find the edges of the real matter at hand.

UX Strategist and Consultant, William Hudson explains “How Might We” questions in this video:

Use a variety of ideation methods: For example, in the divergent stage, teams can apply methods such as random metaphors or bad ideas to venture into a vast expanse of uncharted territory. With random metaphors, a team prompts innovation by drawing creative associations. With bad ideas, the point is to come up with ideas that are weird, wild and outrageous, as team members can then determine if valuable points exist in the idea—or a “bad” idea might even expose flaws in conventional ways of seeing problems and situations.

Professor Alan Dix explains important points about bad ideas:

- Copyright holder: William Heath Robinson. Appearance time: 1:30 - 1:33 Copyright license and terms: Public domain. Link: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/c/c9/William_Heath_Robinson_Inventions_-_Page_142.png

- Copyright holder: Rev Stan. Appearance time: 1:40 - 1:44 Copyright license and terms: CC BY 2.0 Link: As yummy as chocolate teapot courtesy of Choccywoccydoodah… _ Flickr.html

- Copyright holder: Fabel. Appearance time: 7:18 - 7:24 Copyright license and terms: CC BY-SA 3.0 Link: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hammer_nails_smithonian.jpg

- Copyright holder: Marcus Hansson. Appearance time: 05:54 - 05:58 Copyright license and terms: CC BY 2.0 Link: https://www.flickr.com/photos/marcus_hansson/7758775386

What Special Considerations Should Designers Have for CPS?

Creative problem solving isn’t the only process design teams consider when thinking of potential risks. Teams that involve themselves in ideation sessions can run into problems, especially if they aren’t aware of them. Here are the main areas to watch:

Bias is natural and human. Unfortunately, it can get in the way of user research and prevent a team from being truly creative and innovative. What’s more, it can utterly hinder the iterative process that should drive creative ideas to the best destinations. Bias takes many forms. It can rear its head without a design team member even realizing it. So, it’s vital to remember this and check it. One team member may examine an angle of the problem at hand and unconsciously view it through a lens. Then, they might voice a suggestion without realizing how they might have framed it for team members to hear. Another risk is that other team members might, for example, apply confirmation bias and overlook important points about potential solutions because they’re not in line with what they’re looking for.

Professor Alan Dix explains bias and fixation as obstacles in creative problem solving examples, and how to overcome them:

Conventionalism

Even in the most hopeful ideation sessions, there’s the risk that some team members may slide back to conventional ways to address a problem. They might climb back inside “the box” and not even realize it. That’s why it’s important to mindfully explore new idea territories around the situation under scrutiny and not merely toy with the notion while clinging to a default “traditional” approach, just because it’s the way the brand or others have “always done things.”

Dominant Personalities and Rank Pulling

As with any group discussion, it’s vital for the facilitator to ensure that everyone has the chance to contribute. Team members with “louder” personalities can dominate the discussions and keep quieter members from offering their thoughts. Plus, without a level playing field, it can be hard for more junior members to join in without feeling a sense of talking out of place or even a fear of reprisal for disagreeing with senior members.

Another point is that ideation sessions naturally involve asking many questions, which can bring on two issues. First, some individuals may over-defend their ideas as they’re protective of them. Second, team members may feel self-conscious as they might think if they ask many questions that it makes them appear frivolous or unintelligent. So, it’s vital for facilitators to ensure that all team members can speak up and ask away, both in divergent thinking sessions when they can offer ideas and convergent thinking sessions when they analyze others’ ideas.

Premature Commitment

Another potential risk to any creativity exercise is that once a team senses a solution is the “best” one, everyone can start to shut off and overlook the chance that an alternative may still arise. This could be a symptom of ideation fatigue or a false consensus that a proposed solution is infallible. So, it’s vital that team members keep open minds and try to catch potential issues with the best-looking solution as early as possible. The key is an understanding of the need for iteration—something that’s integral to the design thinking process, for example.

Overall, creative problem solving can help give a design team the altitude—and attitude—they need to explore the problem and solution spaces thoroughly. Team members can leverage a range of techniques to trawl through the hordes of possibilities that exist for virtually any design scenario. As with any method or tool, though, it takes mindful application and awareness of potential hazards to wield it properly. The most effective creative problem-solving sessions will be ones that keep “creative,” “problem” and “solving” in sharp focus until what emerges for the target audience proves to be more than the sum of these parts.

Learn More About Creative Problem Solving

Take our course, Creativity: Methods to Design Better Products and Services .

Watch our Master Class Harness Your Creativity To Design Better Products with Alan Dix, Professor, Author and Creativity Expert.

Read our piece, 10 Simple Ideas to Get Your Creative Juices Flowing .

Go to Exploring the Art of Innovation: Design Thinking vs. Creative Problem Solving by Marcino Waas for further details.

Consult Creative Problem Solving by Harrison Stamell for more insights.

Read The Osborn Parnes Creative Problem-Solving Process by Leigh Espy for additional information.

See History of the creative problem-solving process by Jo North for more on the history of Creative Problem Solving.

Questions about Creative Problem Solving

To start with, work to understand the user’s needs and pain points. Do your user research—interviews, surveys and observations are helpful, for instance. Analyze this data so you can spot patterns and insights. Define the problem clearly—and it needs to be extremely clear for the solution to be able to address it—and make sure it lines up with the users’ goals and your project’s objectives.

You and your design team might hold a brainstorming session. It could be a variation such as brainwalking—where you move about the room ideating—or brainwriting, where you write down ideas. Alternatively, you could try generating weird and wonderful notions in a bad ideas ideation session.

There’s a wealth of techniques you can use. In any case, engage stakeholders in brainstorming sessions to bring different perspectives on board the team’s trains of thought. What’s more, you can use tools like a Problem Statement Template to articulate the problem concisely.

Take our course, Creativity: Methods to Design Better Products and Services .

Watch as Author and Human-Computer Interaction Expert, Professor Alan Dix explains important points about bad ideas:

Some things you might try are: 1. Change your environment: A new setting can stimulate fresh ideas. So, take a walk, visit a different room, or work outside.

2. Try to break the problem down into smaller parts: Focus on just one piece at a time—that should make the task far less overwhelming. Use techniques like mind mapping so you can start to visualize connections and come up with ideas.

3. Step away from work and indulge in activities that relax your mind: Is it listening to music for you? Or how about drawing? Or exercising? Whatever it is, if you break out of your routine and get into a relaxation groove, it can spark new thoughts and perspectives.

4. Collaborate with others: Discuss the problem with colleagues, stakeholders, or—as long as you don’t divulge sensitive information or company secrets—friends. It can help you to get different viewpoints, and sometimes those new angles and fresh perspectives can help unlock a solution.

5. Set aside dedicated time for creative thinking: Take time to get intense with creativity; prevent distractions and just immerse yourself in the problem as fully as you can with your team. Use techniques like brainstorming or the "Six Thinking Hats" to travel around the problem space and explore a wealth of angles.

Remember, a persistent spirit and an open mind are key; so, keep experimenting with different approaches until you get that breakthrough.

Watch as Professor Alan Dix explains important aspects of creativity and how to handle creative blocks:

Read our piece, 10 Simple Ideas to Get Your Creative Juices Flowing .

Watch as Professor Alan Dix explains the Six Thinking Hats ideation technique.

Creative thinking is about coming up with new and innovative ideas by looking at problems from different angles—and imagining solutions that are truly fresh and unique. It takes an emphasis on divergent thinking to get “out there” and be original in the problem space. You can use techniques like brainstorming, mind mapping and free association to explore hordes of possibilities, many of which might be “hiding” in obscure corners of your—or someone on your team’s—imagination.

Critical thinking is at the other end of the scale. It’s the convergent half of the divergent-convergent thinking approach. In that approach, once the ideation team have hauled in a good catch of ideas, it’s time for team members to analyze and evaluate these ideas to see how valid and effective each is. Everyone strives to consider the evidence, draw logical connections and eliminate any biases that could be creeping in to cloud judgments. Accuracy, sifting and refining are watchwords here.

Watch as Professor Alan Dix explains divergent and convergent thinking:

The tools you can use are in no short supply, and they’re readily available and inexpensive, too. Here are a few examples:

Tools like mind maps are great ways to help you visualize ideas and make connections between them and elements within them. Try sketching out your thoughts and see how they relate to each other—you might discover unexpected gems, or germs of an idea that can splinter into something better, with more thought and development.

The SCAMPER technique is another one you can try. It can help you catapult your mind into a new idea space as you Substitute, Combine, Adapt, Modify, Put to another use, Eliminate, and Reverse aspects of the problem you’re considering.

The “5 Whys” technique is a good one to drill down to root causes with. Once you’ve spotted a problem, you can start working your way back to see what’s behind it. Then you do the same to work back to the cause of the cause. Keep going; usually five times will be enough to see what started the other problems as the root cause.

Watch as the Father of UX Design, Don Norman explains the 5 Whys technique:

Read all about SCAMPER in our topic definition of it.

It’s natural for some things to get in the way of being creative in the face of a problem. It can be challenging enough to ideate creatively on your own, but it’s especially the case in group settings. Here are some common obstacles:

1. Fear of failure or appearing “silly”: when people worry about making mistakes or sounding silly, they avoid taking risks and exploring new ideas. This fear stifles creativity. That’s why ideation sessions like bad ideas are so valuable—it turns this fear on its head.

2. Rigid thinking: This can also raise itself as a high and thick barrier. If someone in an ideation session clings to established ways to approach problems (and potential solutions), it can hamper their ability to see different perspectives, let alone agree with them. They might even comment critically to dampen what might just be the brightest way forward. It takes an open mind and an awareness of one’s own bias to overcome this.

3. Time pressure and resource scarcity: When a team has tight deadlines to work to, they may rush to the first workable solution and ignore a wide range of possibilities where the true best solution might be hiding. That’s why stakeholders and managers should give everyone enough time—as well as any needed tools, materials and support—to ideate and experiment. The best solution is in everybody’s interest, after all.

It takes a few ingredients to get the environment just right for creative problem solving:

Get in the mood for creativity: This could be a relaxing activity before you start your session, or a warm-up activity in the room. Then, later, encourage short breaks—they can rejuvenate the mind and help bring on fresh insights.

Get the physical environment just right for creating problem solving: You and your team will want a comfortable and flexible workspace—preferably away from your workstations. Make sure the room is one where people can collaborate easily and also where they can work quietly. A meeting room is good as it will typically have room for whiteboards and comfortable space for group discussion. Note: you’ll also need sticky notes and other art supplies like markers.

Make the atmosphere conducive for creative problem solving: Someone will need to play facilitator so everyone has some ground rules to work with. Encourage everyone to share ideas, that all ideas are valuable, and that egos and seniority have no place in the room. Of course, this may take some enforcement and repetition—especially as "louder" team members may try to dominate proceedings, anyway, and others may be self-conscious about sounding "ridiculous."

Make sure you’ve got a diverse team: Diversity means different perspectives, which means richer and more innovative solutions can turn up. So, try to include individuals with different backgrounds, skills and viewpoints—sometimes, non-technical mindsets can spot ideas and points in a technical realm, which experienced programmers might miss, for instance.

Watch our Master Class Harness Your Creativity To Design Better Products with Alan Dix, Professor, Author and Creativity Expert.

Ideating alone? Watch as Professor Alan Dix gives valuable tips about how to nurture creativity:

- Copyright holder: GerritR. Appearance time: 6:54 - 6:59 Copyright license and terms: CC-BY-SA-4.0 Link: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Blick_auf_das_Dylan_Thomas_Boathouse_und_die_Trichterm%C3%BCndung_des_Taf,_Wales.jpg

Research plays a crucial role in any kind of creative problem solving, and in creative problem solving itself it’s about collecting information about the problem—and, by association, the users themselves. You and your team members need to have a well-defined grasp of what you’re facing before you can start reaching out into the wide expanses of the idea space.

Research helps you lay down a foundation of knowledge and avoid reinventing the wheel. Also, if you study existing solutions and industry trends, you’ll be able to understand what has worked before and what hasn't.

What’s more, research is what will validate the ideas that come out of your ideation efforts. From testing concepts and prototypes with real users, you’ll get precious input about your creative solutions so you can fine-tune them to be innovative and practical—and give users what they want in a way that’s fresh and successful.

Watch as UX Strategist and Consultant, William Hudson explains important points about user research:

First, it’s crucial for a facilitator to make sure the divergent stage of the creative problem solving is over and your team is on to the convergent stage. Only then should any analysis happen.

If others are being critical of your creative solutions, listen carefully and stay open-minded. Look on it as a chance to improve, and don’t take it personally. Indeed, the session facilitator should moderate to make sure everyone understands the nature of constructive criticism.

If something’s unclear, be sure to ask the team member to be more specific, so you can understand their points clearly.

Then, reflect on what you’ve heard. Is it valid? Something you can improve or explain? For example, in a bad ideas session, there may be an aspect of your idea that you can develop among the “bad” parts surrounding it.

So, if you can, clarify any misunderstandings and explain your thought process. Just stay positive and calm and explain things to your critic and other team member. The insights you’ve picked up may strengthen your solution and help to refine it.

Last—but not least—make sure you hear multiple perspectives. When you hear from different team members, chances are you’ll get a balanced view. It can also help you spot common themes and actionable improvements you might make.

Watch as Todd Zaki Warfel, Author, Speaker and Leadership Coach, explains how to present design ideas to clients, a valuable skill in light of discussing feedback from stakeholders.

Lateral thinking is a technique where you approach problems from new and unexpected angles. It encourages you to put aside conventional step-by-step logic and get “out there” to explore creative and unorthodox solutions. Author, physician and commentator Edward de Bono developed lateral thinking as a way to help break free from traditional patterns of thought.

In creative problem solving, you can use lateral thinking to come up with truly innovative ideas—ones that standard logical processes might overlook. It’s about bypassing these so you can challenge assumptions and explore alternatives that point you and your team to breakthrough solutions.

You can use techniques like brainstorming to apply lateral thinking and access ideas that are truly “outside the box” and what your team, your brand and your target audience really need to work on.

Professor Alan Dix explains lateral thinking in this video:

1. Baer, J. (2012). Domain Specificity and The Limits of Creativity Theory . The Journal of Creative Behavior, 46(1), 16–29. John Baer's influential paper challenged the notion of a domain-general theory of creativity and argued for the importance of considering domain-specific factors in creative problem solving. This work has been highly influential in shaping the understanding of creativity as a domain-specific phenomenon and has implications for the assessment and development of creativity in various domains.

2. Runco, M. A., & Jaeger, G. J. (2012). The Standard Definition of Creativity . Creativity Research Journal, 24(1), 92–96. Mark A. Runco and Gerard J. Jaeger's paper proposed a standard definition of creativity, which has been widely adopted in the field. They defined creativity as the production of original and effective ideas, products, or solutions that are appropriate to the task at hand. This definition has been influential in providing a common framework for creativity research and assessment.

1. Fogler, H. S., LeBlanc, S. E., & Rizzo, B. (2014). Strategies for Creative Problem Solving (3rd ed.). Prentice Hall.

This book focuses on developing creative problem-solving strategies, particularly in engineering and technical contexts. It introduces various heuristic problem-solving techniques, optimization methods, and design thinking principles. The authors provide a systematic framework for approaching ill-defined problems, generating and implementing solutions, and evaluating the outcomes. With its practical exercises and real-world examples, this book has been influential in equipping professionals and students with the skills to tackle complex challenges creatively.

2. De Bono, E. (1985). Six Thinking Hats . Little, Brown and Company.

Edward de Bono's Six Thinking Hats introduces a powerful technique for parallel thinking and decision-making. The book outlines six different "hats" or perspectives that individuals can adopt to approach a problem or situation from various angles. This structured approach encourages creative problem-solving by separating different modes of thinking, such as emotional, logical, and creative perspectives. De Bono's work has been highly influential in promoting lateral thinking and providing a practical framework for group problem solving.

3. Osborn, A. F. (1963). Applied Imagination: Principles and Procedures of Creative Problem-Solving (3rd ed.). Charles Scribner's Sons.

Alex F. Osborn's Applied Imagination is a pioneering work that introduced the concept of brainstorming and other creative problem-solving techniques. Osborn emphasized how important it is to defer judgment and generate a large quantity of ideas before evaluating them. This book laid the groundwork for many subsequent developments in the field of creative problem-solving, and it’s been influential in promoting the use of structured ideation processes in various domains.

Answer a Short Quiz to Earn a Gift

What is the first stage in the creative problem-solving process?

- Implementation

- Idea Generation

- Problem Identification

Which technique is commonly used during the idea generation stage of creative problem-solving?

- Brainstorming

- Prototyping

What is the main purpose of the evaluation stage in creative problem-solving?

- To generate as many ideas as possible

- To implement the solution

- To assess the feasibility and effectiveness of ideas

In the creative problem-solving process, what often follows after implementing a solution?

- Testing and Refinement

Which stage in the creative problem-solving process focuses on generating multiple possible solutions?

Better luck next time!

Do you want to improve your UX / UI Design skills? Join us now

Congratulations! You did amazing

You earned your gift with a perfect score! Let us send it to you.

Check Your Inbox

We’ve emailed your gift to [email protected] .

Literature on Creative Problem Solving

Here’s the entire UX literature on Creative Problem Solving by the Interaction Design Foundation, collated in one place:

Learn more about Creative Problem Solving

Take a deep dive into Creative Problem Solving with our course Creativity: Methods to Design Better Products and Services .

The overall goal of this course is to help you design better products, services and experiences by helping you and your team develop innovative and useful solutions. You’ll learn a human-focused, creative design process.

We’re going to show you what creativity is as well as a wealth of ideation methods ―both for generating new ideas and for developing your ideas further. You’ll learn skills and step-by-step methods you can use throughout the entire creative process. We’ll supply you with lots of templates and guides so by the end of the course you’ll have lots of hands-on methods you can use for your and your team’s ideation sessions. You’re also going to learn how to plan and time-manage a creative process effectively.

Most of us need to be creative in our work regardless of if we design user interfaces, write content for a website, work out appropriate workflows for an organization or program new algorithms for system backend. However, we all get those times when the creative step, which we so desperately need, simply does not come. That can seem scary—but trust us when we say that anyone can learn how to be creative on demand . This course will teach you ways to break the impasse of the empty page. We'll teach you methods which will help you find novel and useful solutions to a particular problem, be it in interaction design, graphics, code or something completely different. It’s not a magic creativity machine, but when you learn to put yourself in this creative mental state, new and exciting things will happen.

In the “Build Your Portfolio: Ideation Project” , you’ll find a series of practical exercises which together form a complete ideation project so you can get your hands dirty right away. If you want to complete these optional exercises, you will get hands-on experience with the methods you learn and in the process you’ll create a case study for your portfolio which you can show your future employer or freelance customers.

Your instructor is Alan Dix . He’s a creativity expert, professor and co-author of the most popular and impactful textbook in the field of Human-Computer Interaction. Alan has worked with creativity for the last 30+ years, and he’ll teach you his favorite techniques as well as show you how to make room for creativity in your everyday work and life.

You earn a verifiable and industry-trusted Course Certificate once you’ve completed the course. You can highlight it on your resume , your LinkedIn profile or your website .

All open-source articles on Creative Problem Solving

10 simple ideas to get your creative juices flowing.

- 4 years ago

Open Access—Link to us!

We believe in Open Access and the democratization of knowledge . Unfortunately, world-class educational materials such as this page are normally hidden behind paywalls or in expensive textbooks.

If you want this to change , cite this page , link to us, or join us to help us democratize design knowledge !

Privacy Settings

Our digital services use necessary tracking technologies, including third-party cookies, for security, functionality, and to uphold user rights. Optional cookies offer enhanced features, and analytics.

Experience the full potential of our site that remembers your preferences and supports secure sign-in.

Governs the storage of data necessary for maintaining website security, user authentication, and fraud prevention mechanisms.

Enhanced Functionality

Saves your settings and preferences, like your location, for a more personalized experience.

Referral Program

We use cookies to enable our referral program, giving you and your friends discounts.

Error Reporting

We share user ID with Bugsnag and NewRelic to help us track errors and fix issues.

Optimize your experience by allowing us to monitor site usage. You’ll enjoy a smoother, more personalized journey without compromising your privacy.

Analytics Storage

Collects anonymous data on how you navigate and interact, helping us make informed improvements.

Differentiates real visitors from automated bots, ensuring accurate usage data and improving your website experience.

Lets us tailor your digital ads to match your interests, making them more relevant and useful to you.

Advertising Storage

Stores information for better-targeted advertising, enhancing your online ad experience.

Personalization Storage

Permits storing data to personalize content and ads across Google services based on user behavior, enhancing overall user experience.

Advertising Personalization

Allows for content and ad personalization across Google services based on user behavior. This consent enhances user experiences.

Enables personalizing ads based on user data and interactions, allowing for more relevant advertising experiences across Google services.

Receive more relevant advertisements by sharing your interests and behavior with our trusted advertising partners.

Enables better ad targeting and measurement on Meta platforms, making ads you see more relevant.

Allows for improved ad effectiveness and measurement through Meta’s Conversions API, ensuring privacy-compliant data sharing.

LinkedIn Insights

Tracks conversions, retargeting, and web analytics for LinkedIn ad campaigns, enhancing ad relevance and performance.

LinkedIn CAPI

Enhances LinkedIn advertising through server-side event tracking, offering more accurate measurement and personalization.

Google Ads Tag

Tracks ad performance and user engagement, helping deliver ads that are most useful to you.

Share Knowledge, Get Respect!

or copy link

Cite according to academic standards

Simply copy and paste the text below into your bibliographic reference list, onto your blog, or anywhere else. You can also just hyperlink to this page.

New to UX Design? We’re Giving You a Free ebook!

Download our free ebook “ The Basics of User Experience Design ” to learn about core concepts of UX design.

In 9 chapters, we’ll cover: conducting user interviews, design thinking, interaction design, mobile UX design, usability, UX research, and many more!

- Skip to main content

- Skip to header right navigation

- Skip to site footer

Unleash Your Greatest Leadership Impact

What is Creative Problem Solving?

“Every problem is an opportunity in disguise.” — John Adams

Imagine if you come up with new ideas and solve problems better, faster, easier?

Imagine if you could easily leverage the thinking from multiple experts and different points of view?

That’s the promise and the premise of Creative Problem Solving.

As Einstein put it, “Creativity is intelligence having fun.”

Creative problem solving is a systematic approach that empowers individuals and teams to unleash their imagination , explore diverse perspectives, and generate innovative solutions to complex challenges.

Throughout my years at Microsoft, I’ve used variations of Creative Problem Solving to tackle big, audacious challenges and create new opportunities for innovation.

I this article, I walkthrough the original Creative Problem Solving process and variations so that you can more fully appreciate the power of the process and how it’s evolved over the years.

On This Page

Innovation is a Team Sport What is Creative Problem Solving? What is the Creative Problem Solving Process? Variations of Creative Problem Solving Osborn-Parnes Creative Problem Solving Criticisms of Creative Problem Solving Creative Problem Solving 21st Century FourSight Thinking Profiles Basadur’s Innovative Process Synetics SCAMPER Design Thinking

Innovation is a Team Sport

Recognizing that innovation is a team sport , I understood the importance of equipping myself and my teams with the right tools for the job.

By leveraging different problem-solving approaches, I have been able to navigate complex landscapes , think outside the box, and find unique solutions.

Creative Problem Solving has served as a valuable compass , guiding me to explore uncharted territories and unlock the potential for groundbreaking ideas.

With a diverse set of tools in my toolbox, I’ve been better prepared to navigate the dynamic world of innovation and contribute to the success and amplify impact for many teams and many orgs for many years.

By learning and teaching Creative Problem Solving we empower diverse teams to appreciate and embrace cognitive diversity to solve problems and create new opportunities with skill.

Creative problem solving is a mental process used to find original and effective solutions to problems.

It involves going beyond traditional methods and thinking outside the box to come up with new and innovative approaches.

Here are some key aspects of creative problem solving:

- Divergent Thinking : This involves exploring a wide range of possibilities and generating a large number of ideas, even if they seem unconventional at first.

- Convergent Thinking : Once you have a pool of ideas, you need to narrow them down and select the most promising ones. This requires critical thinking and evaluation skills.

- Process : There are various frameworks and techniques that can guide you through the creative problem-solving process. These can help you structure your thinking and increase your chances of finding innovative solutions.

Benefits of Creative Problem Solving:

- Finding New Solutions : It allows you to overcome challenges and achieve goals in ways that traditional methods might miss.

- Enhancing Innovation : It fosters a culture of innovation and helps organizations stay ahead of the curve.

- Improved Adaptability : It equips you to handle unexpected situations and adapt to changing circumstances.

- Boosts Confidence: Successfully solving problems with creative solutions can build confidence and motivation.

Here are some common techniques used in creative problem solving:

- Brainstorming : This is a classic technique where you generate as many ideas as possible in a short period of time.

- SCAMPER: This is a framework that prompts you to consider different ways to Substitute, Combine, Adapt, Magnify/Minify, Put to other uses, Eliminate, and Rearrange elements of the problem.

- Mind Mapping: This technique involves visually organizing your ideas and connections between them.

- Lateral Thinking: This approach challenges you to look at the problem from different angles and consider unconventional solutions.

Creative problem solving is a valuable skill for everyone, not just artists or designers.

You can apply it to all aspects of life, from personal challenges to professional endeavors.

What is the Creative Problem Solving Process?

The Creative Problem Solving (CPS) framework is a systematic approach for generating innovative solutions to complex problems.

It’s effectively a process framework.

It provides a structured process that helps individuals and teams think creatively, explore possibilities, and develop practical solutions.

The Creative Problem Solving process framework typically consists of the following stages:

- Clarify : In this stage, the problem or challenge is clearly defined, ensuring a shared understanding among participants. The key objectives, constraints, and desired outcomes are identified.

- Generate Ideas : During this stage, participants engage in divergent thinking to generate a wide range of ideas and potential solutions. The focus is on quantity and deferring judgment, encouraging free-flowing creativity.

- Develop Solutions : In this stage, the generated ideas are evaluated, refined, and developed into viable solutions. Participants explore the feasibility, practicality, and potential impact of each idea, considering the resources and constraints at hand.

- Implement : Once a solution or set of solutions is selected, an action plan is developed to guide the implementation process. This includes defining specific steps, assigning responsibilities, setting timelines, and identifying the necessary resources.

- Evaluate : After implementing the solution, the outcomes and results are evaluated to assess the effectiveness and impact. Lessons learned are captured to inform future problem-solving efforts and improve the process.

Throughout the Creative Problem Solving framework, various creativity techniques and tools can be employed to stimulate idea generation, such as brainstorming, mind mapping, SCAMPER (Substitute, Combine, Adapt, Modify, Put to another use, Eliminate, Reverse), and others.

These techniques help break through traditional thinking patterns and encourage novel approaches to problem-solving.

What are Variations of the Creative Problem Solving Process?

There are several variations of the Creative Problem Solving process, each emphasizing different steps or stages.

Here are five variations that are commonly referenced:

- Osborn-Parnes Creative Problem Solving : This is one of the earliest and most widely used versions of Creative Problem Solving. It consists of six stages: Objective Finding, Fact Finding, Problem Finding, Idea Finding, Solution Finding, and Acceptance Finding. It follows a systematic approach to identify and solve problems creatively.

- Creative Problem Solving 21st Century : Creative Problem Solving 21st Century, developed by Roger Firestien, is an innovative approach that empowers individuals to identify and take action towards achieving their goals, wishes, or challenges by providing a structured process to generate ideas, develop solutions, and create a plan of action.

- FourSight Thinking Profiles : This model introduces four stages in the Creative Problem Solving process: Clarify, Ideate, Develop, and Implement. It emphasizes the importance of understanding the problem, generating a range of ideas, developing and evaluating those ideas, and finally implementing the best solution.

- Basadur’s Innovative Process : Basadur’s Innovative Process, developed by Min Basadur, is a systematic and iterative process that guides teams through eight steps to effectively identify, define, generate ideas, evaluate, and implement solutions, resulting in creative and innovative outcomes.

- Synectics : Synectics is a Creative Problem Solving variation that focuses on creating new connections and insights. It involves stages such as Problem Clarification, Idea Generation, Evaluation, and Action Planning. Synectics encourages thinking from diverse perspectives and applying analogical reasoning.

- SCAMPER : SCAMPER is an acronym representing different creative thinking techniques to stimulate idea generation. Each letter stands for a strategy: Substitute, Combine, Adapt, Modify, Put to another use, Eliminate, and Rearrange. SCAMPER is used as a tool within the Creative Problem Solving process to generate innovative ideas by applying these strategies.

- Design Thinking : While not strictly a variation of Creative Problem Solving, Design Thinking is a problem-solving approach that shares similarities with Creative Problem Solving. It typically includes stages such as Empathize, Define, Ideate, Prototype, and Test. Design Thinking focuses on understanding users’ needs, ideating and prototyping solutions, and iterating based on feedback.

These are just a few examples of variations within the Creative Problem Solving framework. Each variation provides a unique perspective on the problem-solving process, allowing individuals and teams to approach challenges in different ways.

Osborn-Parnes Creative Problem Solving (CPS)

The original Creative Problem Solving (CPS) process, developed by Alex Osborn and Sidney Parnes, consists of the following steps:

- Objective Finding : In this step, the problem or challenge is clearly defined, and the objectives and goals are established. It involves understanding the problem from different perspectives, gathering relevant information, and identifying the desired outcomes.

- Fact Finding : The objective of this step is to gather information, data, and facts related to the problem. It involves conducting research, analyzing the current situation, and seeking a comprehensive understanding of the factors influencing the problem.

- Problem Finding : In this step, the focus is on identifying the root causes and underlying issues contributing to the problem. It involves reframing the problem, exploring it from different angles, and asking probing questions to uncover insights and uncover potential areas for improvement.

- Idea Finding : This step involves generating a wide range of ideas and potential solutions. Participants engage in divergent thinking techniques, such as brainstorming, to produce as many ideas as possible without judgment or evaluation. The aim is to encourage creativity and explore novel possibilities.

- Solution Finding : After generating a pool of ideas, the next step is to evaluate and select the most promising solutions. This involves convergent thinking, where participants assess the feasibility, desirability, and viability of each idea. Criteria are established to assess and rank the solutions based on their potential effectiveness.

- Acceptance Finding : In this step, the selected solution is refined, developed, and adapted to fit the specific context and constraints. Strategies are identified to overcome potential obstacles and challenges. Participants work to gain acceptance and support for the chosen solution from stakeholders.

- Solution Implementation : Once the solution is finalized, an action plan is developed to guide its implementation. This includes defining specific steps, assigning responsibilities, setting timelines, and securing the necessary resources. The solution is put into action, and progress is monitored to ensure successful execution.

- Monitoring and Evaluation : The final step involves tracking the progress and evaluating the outcomes of the implemented solution. Lessons learned are captured, and feedback is gathered to inform future problem-solving efforts. This step helps refine the process and improve future problem-solving endeavors.

The CPS process is designed to be iterative and flexible, allowing for feedback loops and refinement at each stage. It encourages collaboration, open-mindedness, and the exploration of diverse perspectives to foster creative problem-solving and innovation.

Criticisms of the Original Creative Problem Solving Approach

While Osborn-Parnes Creative Problem Solving is a widely used and effective problem-solving framework, it does have some criticisms, challenges, and limitations.

These include:

- Linear Process : CPS follows a structured and linear process, which may not fully capture the dynamic and non-linear nature of complex problems.

- Overemphasis on Rationality : CPS primarily focuses on logical and rational thinking, potentially overlooking the value of intuitive or emotional insights in the problem-solving process.

- Limited Cultural Diversity : The CPS framework may not adequately address the cultural and contextual differences that influence problem-solving approaches across diverse groups and regions.

- Time and Resource Intensive : Implementing the CPS process can be time-consuming and resource-intensive, requiring significant commitment and investment from participants and organizations.

- Lack of Flexibility : The structured nature of CPS may restrict the exploration of alternative problem-solving methods, limiting adaptability to different situations or contexts.

- Limited Emphasis on Collaboration : Although CPS encourages group participation, it may not fully leverage the collective intelligence and diverse perspectives of teams, potentially limiting the effectiveness of collaborative problem-solving.

- Potential Resistance to Change : Organizations or individuals accustomed to traditional problem-solving approaches may encounter resistance or difficulty in embracing the CPS methodology and its associated mindset shift.

Despite these criticisms and challenges, the CPS framework remains a valuable tool for systematic problem-solving.

Adapting and supplementing it with other methodologies and approaches can help overcome some of its limitations and enhance overall effectiveness.

Creative Problem Solving 21st Century

Roger Firestien is a master facilitator of the Creative Problem Solving process. He has been using it, studying it, researching it, and teaching it for 40 years.

According to him, the 21st century requires a new approach to problem-solving that is more creative and innovative.

He has developed a program that focuses on assisting facilitators of the Creative Problem Solving Process to smoothly and confidently transition from one stage to the next in the Creative Problem Solving process as well as learn how to talk less and accomplish more while facilitating Creative Problem Solving.

Creative Problem Solving empowers individuals to identify and take action towards achieving their goals, manifesting their aspirations, or addressing challenges they wish to overcome.

Unlike approaches that solely focus on problem-solving, CPS recognizes that the user’s objective may not necessarily be framed as a problem. Instead, CPS supports users in realizing their goals and desires, providing a versatile framework to guide them towards success.

Why Creative Problem Solving 21st Century?

Creative Problem Solving 21st Century addresses challenges with the original Creative Problem Solving method by adapting it to the demands of the modern era. Roger Firestien recognized that the 21st century requires a new approach to problem-solving that is more creative and innovative.

The Creative Problem Solving 21st Century program focuses on helping facilitators smoothly transition between different stages of the problem-solving process. It also teaches them how to be more efficient and productive in their facilitation by talking less and achieving more results.

Unlike approaches that solely focus on problem-solving, Creative Problem Solving 21st Century acknowledges that users may not always frame their objectives as problems. It recognizes that individuals have goals, wishes, and challenges they want to address or achieve. Creative Problem Solving provides a flexible framework to guide users towards success in realizing their aspirations.

Creative Problem Solving 21st Century builds upon the foundational work of pioneers such as Osborn, Parnes, Miller, and Firestien. It incorporates practical techniques like PPC (Pluses, Potentials, Concerns) and emphasizes the importance of creative leadership skills in driving change.

Stages of the Creative Problem Solving 21st Century

- Clarify the Problem

- Generate Ideas

- Develop Solutions

- Plan for Action

Steps of the Creative Problem Solving 21st Century

Here are stages and steps of the Creative Problem Solving 21st Century per Roger Firestien:

CLARIFY THE PROBLEM

Start here when you are looking to improve, create, or solve something. You want to explore the facts, feelings and data around it. You want to find the best problem to solve.

IDENTIFY GOAL, WISH OR CHALLENGE Start with a goal, wish or challenge that begins with the phrase: “I wish…” or “It would be great if…”

Diverge : If you are not quite clear on a goal then create, invent, solve or improve.

Converge : Select the goal, wish or challenge on which you have Ownership, Motivation and a need for Imagination.

GATHER DATA

Diverge : What is a brief history of your goal, wish or challenge? What have you already thought of or tried? What might be your ideal goal?

Converge : Select the key data that reveals a new insight into the situation or that is important to consider throughout the remainder of the process.

Diverge : Generate many questions about your goal, wish or challenge. Phrase your questions beginning with: “How to…?” “How might…?” “What might be all the ways to…?” Try turning your key data into questions that redefine the goal, wish or challenge.

- Mark the “HITS” : New insight. Promising direction. Nails it! Feels good in your gut.

- Group the related “HITS” together.

- Restate the cluster . “How to…” “What might be all the…”

GENERATE IDEAS

Start here when you have a clearly defined problem and you need ideas to solve it. The best way to create great ideas is to generate LOTS of ideas. Defer judgment. Strive for quantity. Seek wild & unusual ideas. Build on other ideas.

Diverge : Come up with at least 40 ideas for solving your problem. Come up with 40 more. Keep going. Even as you see good ideas emerge, keep pushing for novelty. Stretch!

- Mark the “HITS”: Interesting, Intriguing, Useful, Solves the problem. Sparkles at you.

- Restate the cluster with a verb phrase.

DEVELOP SOLUTIONS

Start here when you want to turn promising ideas into workable solutions.

DEVELOP YOUR SOLUTION Review your clusters of ideas and blend them into a “story.” Imagine in detail what your solution would look like when it is implemented.

Begin your solution story with the phrase, “What I see myself doing is…”

PPCo EVALUATION

PPCo stands for Pluses, Potentials, Concerns and Overcome concerns

Review your solution story .

- List the PLUSES or specific strengths of your solution.

- List the POTENTIALS of your solution. What might be the result if you were to implement your idea?

- Finally, list your CONCERNS about the solution. Phrase your concerns beginning with “How to…”

- Diverge and generate ideas to OVERCOME your concerns one at a time until they have all been overcome