- User Registration

Code of Ethics

Code of ethics.

of the National Association of Social Workers Approved by the 1996 NASW Delegate Assembly and revised by the 2008 NASW Delegate Assembly

To View The Code of Ethics as a PDF Click Here.

The primary mission of the social work profession is to enhance human well¬being and help meet the basic human needs of all people, with particular attention to the needs and empowerment of people who are vulnerable, oppressed, and living in poverty. A historic and defining feature of social work is the profession’s focus on individual well¬being in a social context and the well¬being of society. Fundamental to social work is attention to the environmental forces that create, contribute to, and address problems in living.

Social workers promote social justice and social change with and on behalf of clients. “Clients” is used inclusively to refer to individuals, families, groups, organizations, and communities. Social workers are sensitive to cultural and ethnic diversity and strive to end discrimination, oppression, poverty, and other forms of social injustice. These activities may be in the form of direct practice, community organizing, supervision, consultation administration, advocacy, social and political action, policy development and implementation, education, and research and evaluation. Social workers seek to enhance the capacity of people to address their own needs. Social workers also seek to promote the responsiveness of organizations, communities, and other social institutions to individuals’ needs and social problems.

The mission of the social work profession is rooted in a set of core values. These core values, embraced by social workers throughout the profession’s history, are the foundation of social work’s unique purpose and perspective:

- social justice

- dignity and worth of the person

- importance of human relationships

- competence.

This constellation of core values reflects what is unique to the social work profession. Core values, and the principles that flow from them, must be balanced within the context and complexity of the human experience.

Purpose of the NASW Code of Ethics

Professional ethics are at the core of social work. The profession has an obligation to articulate its basic values, ethical principles, and ethical standards. The NASW Code of Ethics sets forth these values, principles, and standards to guide social workers’ conduct. The Code is relevant to all social workers and social work students, regardless of their professional functions, the settings in which they work, or the populations they serve. The NASW Code of Ethics serves six purposes:

- The Code identifies core values on which social work’s mission is based.

- The Code summarizes broad ethical principles that reflect the profession’s core values and establishes a set of specific ethical standards that should be used to guide social work practice.

- The Code is designed to help social workers identify relevant considerations when professional obligations conflict or ethical uncertainties arise.

- The Code provides ethical standards to which the general public can hold the social work profession accountable.

- The Code socializes practitioners new to the field to social work’s mission, values, ethical principles, and ethical standards.

- The Code articulates standards that the social work profession itself can use to assess whether social workers have engaged in unethical conduct. NASW has formal procedures to adjudicate ethics complaints filed against its members.* In subscribing to this Code, social workers are required to cooperate in its implementation, participate in NASW adjudication proceedings, and abide by any NASW disciplinary rulings or sanctions based on it.

The Code offers a set of values, principles, and standards to guide decision making and conduct when ethical issues arise. It does not provide a set of rules that prescribe how social workers should act in all situations. Specific applications of the Code must take into account the context in which it is being considered and the possibility of conflicts among the Code‘s values, principles, and standards. Ethical responsibilities flow from all human relationships, from the personal and familial to the social and professional.

Further, the NASW Code of Ethics does not specify which values, principles, and standards are most important and ought to outweigh others in instances when they conflict. Reasonable differences of opinion can and do exist among social workers with respect to the ways in which values, ethical principles, and ethical standards should be rank ordered when they conflict. Ethical decision making in a given situation must apply the informed judgment of the individual social worker and should also consider how the issues would be judged in a peer review process where the ethical standards of the profession would be applied.

Ethical decision making is a process. There are many instances in social work where simple answers are not available to resolve complex ethical issues. Social workers should take into consideration all the values, principles, and standards in this Code that are relevant to any situation in which ethical judgment is warranted. Social workers’ decisions and actions should be consistent with the spirit as well as the letter of this Code.

In addition to this Code, there are many other sources of information about ethical thinking that may be useful. Social workers should consider ethical theory and principles generally, social work theory and research, laws, regulations, agency policies, and other relevant codes of ethics, recognizing that among codes of ethics social workers should consider the NASW Code of Ethics as their primary source. Social workers also should be aware of the impact on ethical decision making of their clients’ and their own personal values and cultural and religious beliefs and practices. They should be aware of any conflicts between personal and professional values and deal with them responsibly. For additional guidance social workers should consult the relevant literature on professional ethics and ethical decision making and seek appropriate consultation when faced with ethical dilemmas. This may involve consultation with an agency-based or social work organization’s ethics committee, a regulatory body, knowledgeable colleagues, supervisors, or legal counsel.

Instances may arise when social workers’ ethical obligations conflict with agency policies or relevant laws or regulations. When such con¬flicts occur, social workers must make a responsible effort to resolve the conflict in a manner that is consistent with the values, principles, and standards expressed in this Code. If a reasonable resolution of the conflict does not appear possible, social workers should seek proper consultation before making a decision.

The NASW Code of Ethics is to be used by NASW and by individuals, agencies, organizations, and bodies (such as licensing and regulatory boards, professional liability insurance providers, courts of law, agency boards of directors, government agencies, and other professional groups) that choose to adopt it or use it as a frame of reference. Violation of standards in this Code does not automatically imply legal liability or violation of the law. Such determination can only be made in the context of legal and judicial proceedings. Alleged violations of the Code would be subject to a peer review process. Such processes are generally separate from legal or administrative procedures and insulated from legal review or proceedings to allow the profession to counsel and discipline its own members. A code of ethics cannot guarantee ethical behavior. Moreover, a code of ethics cannot resolve all ethical issues or disputes or capture the richness and complexity involved in striving to make responsible choices within a moral community. Rather, a code of ethics sets forth values, ethical principles, and ethical standards to which professionals aspire and by which their actions can be judged. Social workers’ ethical behavior should result from their personal commitment to engage in ethical practice. The NASW Code of Ethics reflects the commitment of all social workers to uphold the profession’s values and to act ethically. Principles and standards must be applied by individuals of good character who discern moral questions and, in good faith, seek to make reliable ethical judgments.

Ethical Principles

The following broad ethical principles are based on social work’s core values of service, social justice, dignity and worth of the person, importance of human relationships, integrity, and competence. These principles set forth ideals to which all social workers should aspire

Value: Service Ethical Principle: Social workers’ primary goal is to help people in need and to address social problems. Social workers elevate service to others above self-interest. Social workers draw on their knowledge, values, and skills to help people in need and to address social problems. Social workers are encouraged to volunteer some portion of their professional skills with no expectation of significant financial return (pro bono service).

Value: Social Justice

Ethical Principle: Social workers challenge social injustice. Social workers pursue social change, particularly with and on behalf of vulnerable and oppressed individuals and groups of people. Social workers’ social change efforts are focused primarily on issues of poverty, unemployment, discrimination, and other forms of social injustice. These activities seek to promote sensitivity to and knowledge about oppression and cultural and ethnic diversity. Social workers strive to ensure access to needed information, services, and resources; equality of opportunity; and meaningful participation in decision making for all people.

Value: Dignity and Worth of the Person

Ethical Principle: Social workers respect the inherent dignity and worth of the person. Social workers treat each person in a caring and respectful fashion, mindful of individual differences and cultural and ethnic diversity. Social workers promote clients’ socially responsible self¬determination. Social workers seek to enhance clients’ capacity and opportunity to change and to address their own needs. Social workers are cognizant of their dual responsibility to clients and to the broader society. They seek to resolve conflicts between clients’ interests and the broader society’s interests in a socially responsible manner consistent with the values, ethical principles, and ethical standards of the profession.

Value: Importance of Human Relationships

Ethical Principle: Social workers recognize the central importance of human relationships. Social workers understand that relationships between and among people are an important vehicle for change. Social workers engage people as partners in the helping process. Social workers seek to strengthen relationships among people in a purposeful effort to promote, restore, maintain, and enhance the well¬being of individuals, families, social groups, organizations, and communities.

Value: Integrity

Ethical Principle: Social workers behave in a trustworthy manner. Social workers are continually aware of the profession’s mission, values, ethical principles, and ethical standards and practice in a manner consistent with them. Social workers act honestly and responsibly and promote ethical practices on the part of the organizations with which they are affiliated.

Value: Competence

Ethical Principle: Social workers practice within their areas of competence and develop and enhance their professional expertise. Social workers continually strive to increase their professional knowledge and skills and to apply them in practice. Social workers should aspire to contribute to the knowledge base of the profession.

Ethical Standards

The following ethical standards are relevant to the professional activities of all social workers. These standards concern (1) social workers’ ethical responsibilities to clients, (2) social workers’ ethical responsibilities to colleagues, (3) social workers’ ethical responsibilities in practice settings, (4) social workers’ ethical responsibilities as professionals, (5) social workers’ ethical responsibilities to the social work profession, and (6) social workers’ ethical responsibilities to the broader society.

Some of the standards that follow are enforceable guidelines for professional conduct, and some are aspirational. The extent to which each standard is enforceable is a matter of professional judgment to be exercised by those responsible for reviewing alleged violations of ethical standards.

1. SOCIAL WORKERS’ ETHICAL RESPONSIBILITIES TO CLIENTS

1.01 Commitment to Clients Social workers’ primary responsibility is to promote the well¬being of clients. In general, clients’ interests are primary. However, social workers’ responsibility to the larger society or specific legal obligations may on limited occasions supersede the loyalty owed clients, and clients should be so advised. (Examples include when a social worker is required by law to report that a client has abused a child or has threatened to harm self or others.)

1.02 Self¬Determination Social workers respect and promote the right of clients to self¬determination and assist clients in their efforts to identify and clarify their goals. Social workers may limit clients’ right to self¬determination when, in the social workers’ professional judgment, clients’ actions or potential actions pose a serious, foreseeable, and imminent risk to themselves or others. 1.03 Informed Consent

- Social workers should provide services to clients only in the context of a professional relationship based, when appropriate, on valid informed consent. Social workers should use clear and understandable language to inform clients of the purpose of the services, risks related to the services, limits to services because of the requirements of a third¬party payer, relevant costs, reasonable alternatives, clients’ right to refuse or withdraw consent, and the time frame covered by the consent. Social workers should provide clients with an opportunity to ask questions.

- In instances when clients are not literate or have difficulty understanding the primary language used in the practice setting, social workers should take steps to ensure clients’ comprehension. This may include providing clients with a detailed verbal explanation or arranging for a qualified interpreter or translator whenever possible.

- In instances when clients lack the capacity to provide informed consent, social workers should protect clients’ interests by seeking permission from an appropriate third party, informing clients consistent with the clients’ level of understanding. In such instances social workers should seek to ensure that the third party acts in a manner consistent with clients’ wishes and interests. Social workers should take reasonable steps to enhance such clients’ ability to give informed consent.

- In instances when clients are receiving services involuntarily, social workers should provide information about the nature and extent of services and about the extent of clients’ right to refuse service.

- Social workers who provide services via electronic media (such as computer, telephone, radio, and television) should inform recipients of the limitations and risks associated with such services.

- Social workers should obtain clients’ informed consent before audiotaping or videotaping clients or permitting observation of services to clients by a third party.

1.04 Competence

- Social workers should provide services and represent themselves as competent only within the boundaries of their education, training, license, certification, consultation received, supervised experience, or other relevant professional experience.

- Social workers should provide services in substantive areas or use intervention techniques or approaches that are new to them only after engaging in appropriate study, training, consultation, and supervision from people who are competent in those interventions or techniques.

- When generally recognized standards do not exist with respect to an emerging area of practice, social workers should exercise careful judgment and take responsible steps (including appropriate education, research, training, consultation, and supervision) to ensure the competence of their work and to protect clients from harm.

1.05 Cultural Competence and Social Diversity

- Social workers should understand culture and its function in human behavior and society, recognizing the strengths that exist in all cultures.

- Social workers should have a knowledge base of their clients’ cultures and be able to demonstrate competence in the provision of services that are sensitive to clients’ cultures and to differences among people and cultural groups.

- Social workers should obtain education about and seek to understand the nature of social diversity and oppression with respect to race, ethnicity, national origin, color, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity or expression, age, marital status, political belief, religion, immigration status, and mental or physical disability.

1.06 Conflicts of Interest

- Social workers should be alert to and avoid conflicts of interest that interfere with the exercise of professional discretion and impartial judgment. Social workers should inform clients when a real or potential conflict of interest arises and take reasonable steps to resolve the issue in a manner that makes the clients’ interests primary and protects clients’ interests to the greatest extent possible. In some cases, protecting clients’ interests may require termination of the professional relationship with proper referral of the client.

- Social workers should not take unfair advantage of any professional relationship or exploit others to further their personal, religious, political, or business interests.

- Social workers should not engage in dual or multiple relationships with clients or former clients in which there is a risk of exploitation or potential harm to the client. In instances when dual or multiple relationships are unavoidable, social workers should take steps to protect clients and are responsible for setting clear, appropriate, and culturally sensitive boundaries. (Dual or multiple relationships occur when social workers relate to clients in more than one relationship, whether professional, social, or business. Dual or multiple relationships can occur simultaneously or consecutively.)

- When social workers provide services to two or more people who have a relationship with each other (for example, couples, family members), social workers should clarify with all parties which individuals will be considered clients and the nature of social workers’ professional obligations to the various individuals who are receiving services. Social workers who anticipate a conflict of interest among the individuals receiving services or who anticipate having to perform in potentially conflicting roles (for example, when a social worker is asked to testify in a child custody dispute or divorce proceedings involving clients) should clarify their role with the parties involved and take appropriate action to minimize any conflict of interest.

1.07 Privacy and Confidentiality

- Social workers should respect clients’ right to privacy. Social workers should not solicit private information from clients unless it is essential to providing services or conducting social work evaluation or research. Once private information is shared, standards of confidentiality apply.

- Social workers may disclose confidential information when appropriate with valid consent from a client or a person legally authorized to consent on behalf of a client.

- Social workers should protect the confidentiality of all information obtained in the course of professional service, except for compelling professional reasons. The general expectation that social workers will keep information confidential does not apply when disclosure is necessary to prevent serious, foreseeable, and imminent harm to a client or other identifiable person. In all instances, social workers should disclose the least amount of confidential information necessary to achieve the desired purpose; only information that is directly relevant to the purpose for which the disclosure is made should be revealed.

- Social workers should inform clients, to the extent possible, about the disclosure of confidential information and the potential consequences, when feasible before the disclosure is made. This applies whether social workers disclose confidential information on the basis of a legal requirement or client consent.

- Social workers should discuss with clients and other interested parties the nature of confidentiality and limitations of clients’ right to confidentiality. Social workers should review with clients circumstances where confidential information may be requested and where disclosure of confidential information may be legally required. This discussion should occur as soon as possible in the social worker¬client relationship and as needed throughout the course of the relationship.

- When social workers provide counseling services to families, couples, or groups, social workers should seek agreement among the parties involved concerning each individual’s right to confidentiality and obligation to preserve the confidentiality of information shared by others. Social workers should inform participants in family, couples, or group counseling that social workers cannot guarantee that all participants will honor such agreements.

- Social workers should inform clients involved in family, couples, marital, or group counseling of the social worker’s, employer’s, and agency’s policy concerning the social worker’s disclosure of confidential information among the parties involved in the counseling.

- Social workers should not disclose confidential information to third¬party payers unless clients have authorized such disclosure.

- Social workers should not discuss confidential information in any setting unless privacy can be ensured. Social workers should not discuss confidential information in public or semipublic areas such as hallways, waiting rooms, elevators, and restaurants.

- Social workers should protect the confidentiality of clients during legal proceedings to the extent permitted by law. When a court of law or other legally authorized body orders social workers to disclose confidential or privileged information without a client’s consent and such disclosure could cause harm to the client, social workers should request that the court withdraw the order or limit the order as narrowly as possible or maintain the records under seal, unavailable for public inspection.

- Social workers should protect the confidentiality of clients when responding to requests from members of the media.

- Social workers should protect the confidentiality of clients’ written and electronic records and other sensitive information. Social workers should take reasonable steps to ensure that clients’ records are stored in a secure location and that clients’ records are not available to others who are not authorized to have access.

- Social workers should take precautions to ensure and maintain the confidentiality of information transmitted to other parties through the use of computers, electronic mail, facsimile machines, telephones and telephone answering machines, and other electronic or computer technology. Disclosure of identifying information should be avoided whenever possible.

- Social workers should transfer or dispose of clients’ records in a manner that protects clients’ confidentiality and is consistent with state statutes governing records and social work licensure.

- Social workers should take reasonable precautions to protect client confidentiality in the event of the social worker’s termination of practice, incapacitation, or death.

- Social workers should not disclose identifying information when discussing clients for teaching or training purposes unless the client has consented to disclosure of confidential information.

- Social workers should not disclose identifying information when discussing clients with consultants unless the client has consented to disclosure of confidential information or there is a compelling need for such disclosure.

- Social workers should protect the confidentiality of deceased clients consistent with the preceding standards.

1.08 Access to Records

- Social workers should provide clients with reasonable access to records concerning the clients. Social workers who are concerned that clients’ access to their records could cause serious misunderstanding or harm to the client should provide assistance in interpreting the records and consultation with the client regarding the records. Social workers should limit clients’ access to their records, or portions of their records, only in exceptional circumstances when there is compelling evidence that such access would cause serious harm to the client. Both clients’ requests and the rationale for withholding some or all of the record should be documented in clients’ files.

- When providing clients with access to their records, social workers should take steps to protect the confidentiality of other individuals identified or discussed in such records.

1.09 Sexual Relationships

- Social workers should under no circumstances engage in sexual activities or sexual contact with current clients, whether such contact is consensual or forced.

- Social workers should not engage in sexual activities or sexual contact with clients’ relatives or other individuals with whom clients maintain a close personal relationship when there is a risk of exploitation or potential harm to the client. Sexual activity or sexual contact with clients’ relatives or other individuals with whom clients maintain a personal relationship has the potential to be harmful to the client and may make it difficult for the social worker and client to maintain appropriate professional boundaries. Social workers—not their clients, their clients’ relatives, or other individuals with whom the client maintains a personal relationship—assume the full burden for setting clear, appropriate, and culturally sensitive boundaries.

- Social workers should not engage in sexual activities or sexual contact with former clients because of the potential for harm to the client. If social workers engage in conduct contrary to this prohibition or claim that an exception to this prohibition is warranted because of extraordinary circumstances, it is social workers—not their clients—who assume the full burden of demonstrating that the former client has not been exploited, coerced, or manipulated, intentionally or unintentionally.

- Social workers should not provide clinical services to individuals with whom they have had a prior sexual relationship. Providing clinical services to a former sexual partner has the potential to be harmful to the individual and is likely to make it difficult for the social worker and individual to maintain appropriate professional boundaries.

1.10 Physical Contact

Social workers should not engage in physical contact with clients when there is a possibility of psychological harm to the client as a result of the contact (such as cradling or caressing clients). Social workers who engage in appropriate physical contact with clients are responsible for setting clear, appropriate, and culturally sensitive boundaries that govern such physical contact.

1.11 Sexual Harassment Social workers should not sexually harass clients. Sexual harassment includes sexual advances, sexual solicitation, requests for sexual favors, and other verbal or physical conduct of a sexual nature.

1.12 Derogatory Language Social workers should not use derogatory language in their written or verbal communications to or about clients. Social workers should use accurate and respectful language in all communications to and about clients.

1.13 Payment for Services

- When setting fees, social workers should ensure that the fees are fair, reasonable, and commensurate with the services performed. Consideration should be given to clients’ ability to pay.

- Social workers should avoid accepting goods or services from clients as payment for professional services. Bartering arrangements, particularly involving services, create the potential for conflicts of interest, exploitation, and inappropriate boundaries in social workers’ relationships with clients. Social workers should explore and may participate in bartering only in very limited circumstances when it can be demonstrated that such arrangements are an accepted practice among professionals in the local community, considered to be essential for the provision of services, negotiated without coercion, and entered into at the client’s initiative and with the client’s informed consent. Social workers who accept goods or services from clients as payment for professional services assume the full burden of demonstrating that this arrangement will not be detrimental to the client or the professional relationship.

- Social workers should not solicit a private fee or other remuneration for providing services to clients who are entitled to such available services through the social workers’ employer or agency.

1.14 Clients Who Lack Decision¬Making Capacity

When social workers act on behalf of clients who lack the capacity to make informed decisions, social workers should take reasonable steps to safeguard the interests and rights of those clients.

1.15 Interruption of Services

Social workers should make reasonable efforts to ensure continuity of services in the event that services are interrupted by factors such as unavailability, relocation, illness, disability, or death.

1.16 Termination of Services

- Social workers should terminate services to clients and professional relationships with them when such services and relationships are no longer required or no longer serve the clients’ needs or interests.

- Social workers should take reasonable steps to avoid abandoning clients who are still in need of services. Social workers should withdraw services precipitously only under unusual circumstances, giving careful consideration to all factors in the situation and taking care to minimize possible adverse effects. Social workers should assist in making appropriate arrangements for continuation of services when necessary.

- Social workers in fee¬for¬service settings may terminate services to clients who are not paying an overdue balance if the financial contractual arrangements have been made clear to the client, if the client does not pose an imminent danger to self or others, and if the clinical and other consequences of the current nonpayment have been addressed and discussed with the client.

- Social workers should not terminate services to pursue a social, financial, or sexual relationship with a client.

- Social workers who anticipate the termination or interruption of services to clients should notify clients promptly and seek the transfer, referral, or continuation of services in relation to the clients’ needs and preferences.

- Social workers who are leaving an employment setting should inform clients of appropriate options for the continuation of services and of the benefits and risks of the options.

2. SOCIAL WORKERS’ ETHICAL RESPONSIBILITIES TO COLLEAGUES

2.01 Respect

- Social workers should treat colleagues with respect and should represent accurately and fairly the qualifications, views, and obligations of colleagues.

- Social workers should avoid unwarranted negative criticism of colleagues in communications with clients or with other professionals. Unwarranted negative criticism may include demeaning comments that refer to colleagues’ level of competence or to individuals’ attributes such as race, ethnicity, national origin, color, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity or expression, age, marital status, political belief, religion, immigration status, and mental or physical disability.

- Social workers should cooperate with social work colleagues and with colleagues of other professions when such cooperation serves the well¬being of clients.

2.02 Confidentiality

Social workers should respect confidential information shared by colleagues in the course of their professional relationships and transactions. Social workers should ensure that such colleagues understand social workers’ obligation to respect confidentiality and any exceptions related to it.

2.03 Interdisciplinary Collaboration

- Social workers who are members of an interdisciplinary team should participate in and contribute to decisions that affect the well¬being of clients by drawing on the perspectives, values, and experiences of the social work profession. Professional and ethical obligations of the interdisciplinary team as a whole and of its individual members should be clearly established.

- Social workers for whom a team decision raises ethical concerns should attempt to resolve the disagreement through appropriate channels. If the disagreement cannot be resolved, social workers should pursue other avenues to address their concerns consistent with client well¬being.

2.04 Disputes Involving Colleagues

- Social workers should not take advantage of a dispute between a colleague and an employer to obtain a position or otherwise advance the social workers’ own interests.

- Social workers should not exploit clients in disputes with colleagues or engage clients in any inappropriate discussion of conflicts between social workers and their colleagues.

2.05 Consultation

- Social workers should seek the advice and counsel of colleagues whenever such consultation is in the best interests of clients.

- Social workers should keep themselves informed about colleagues’ areas of expertise and competencies. Social workers should seek consultation only from colleagues who have demonstrated knowledge, expertise, and competence related to the subject of the consultation.

- When consulting with colleagues about clients, social workers should disclose the least amount of information necessary to achieve the purposes of the consultation.

2.06 Referral for Services

- Social workers should refer clients to other professionals when the other professionals’ specialized knowledge or expertise is needed to serve clients fully or when social workers believe that they are not being effective or making reasonable progress with clients and that additional service is required.

- Social workers who refer clients to other professionals should take appropriate steps to facilitate an orderly transfer of responsibility. Social workers who refer clients to other professionals should disclose, with clients’ consent, all pertinent information to the new service providers.

- Social workers are prohibited from giving or receiving payment for a referral when no professional service is provided by the referring social worker.

2.07 Sexual Relationships

- Social workers who function as supervisors or educators should not engage in sexual activities or contact with supervisees, students, trainees, or other colleagues over whom they exercise professional authority.

- Social workers should avoid engaging in sexual relationships with colleagues when there is potential for a conflict of interest. Social workers who become involved in, or anticipate becoming involved in, a sexual relationship with a colleague have a duty to transfer professional responsibilities, when necessary, to avoid a conflict of interest.

2.08 Sexual Harassment

Social workers should not sexually harass supervisees, students, trainees, or colleagues. Sexual harassment includes sexual advances, sexual solicitation, requests for sexual favors, and other verbal or physical conduct of a sexual nature.

2.09 Impairment of Colleagues

- Social workers who have direct knowledge of a social work colleague’s impairment that is due to personal problems, psychosocial distress, substance abuse, or mental health difficulties and that interferes with practice effectiveness should consult with that colleague when feasible and assist the colleague in taking remedial action.

- Social workers who believe that a social work colleague’s impairment interferes with practice effectiveness and that the colleague has not taken adequate steps to address the impairment should take action through appropriate channels established by employers, agencies, NASW, licensing and regulatory bodies, and other professional organizations.

2.10 Incompetence of Colleagues

- Social workers who have direct knowledge of a social work colleague’s incompetence should consult with that colleague when feasible and assist the colleague in taking remedial action.

- Social workers who believe that a social work colleague is incompetent and has not taken adequate steps to address the incompetence should take action through appropriate channels established by employers, agencies, NASW, licensing and regulatory bodies, and other professional organizations.

2.11 Unethical Conduct of Colleagues

- Social workers should take adequate measures to discourage, prevent, expose, and correct the unethical conduct of colleagues.

- Social workers should be knowledgeable about established policies and procedures for handling concerns about colleagues’ unethical behavior. Social workers should be familiar with national, state, and local procedures for handling ethics complaints. These include policies and procedures created by NASW, licensing and regulatory bodies, employers, agencies, and other professional organizations.

- Social workers who believe that a colleague has acted unethically should seek resolution by discussing their concerns with the colleague when feasible and when such discussion is likely to be productive.

- When necessary, social workers who believe that a colleague has acted unethically should take action through appropriate formal channels (such as contacting a state licensing board or regulatory body, an NASW committee on inquiry, or other professional ethics committees).

- Social workers should defend and assist colleagues who are unjustly charged with unethical conduct.

3. SOCIAL WORKERS’ ETHICAL RESPONSIBILITIES IN PRACTICE SETTINGS

3.01 Supervision and Consultation

- Social workers who provide supervision or consultation should have the necessary knowledge and skill to supervise or consult appropriately and should do so only within their areas of knowledge and competence.

- Social workers who provide supervision or consultation are responsible for setting clear, appropriate, and culturally sensitive boundaries.

- Social workers should not engage in any dual or multiple relationships with supervisees in which there is a risk of exploitation of or potential harm to the supervisee.

- Social workers who provide supervision should evaluate supervisees’ performance in a manner that is fair and respectful.

3.02 Education and Training

- Social workers who function as educators, field instructors for students, or trainers should provide instruction only within their areas of knowledge and competence and should provide instruction based on the most current information and knowledge available in the profession.

- Social workers who function as educators or field instructors for students should evaluate students’ performance in a manner that is fair and respectful.

- Social workers who function as educators or field instructors for students should take reasonable steps to ensure that clients are routinely informed when services are being provided by students.

- Social workers who function as educators or field instructors for students should not engage in any dual or multiple relationships with students in which there is a risk of exploitation or potential harm to the student. Social work educators and field instructors are responsible for setting clear, appropriate, and culturally sensitive boundaries.

3.03 Performance Evaluation

Social workers who have responsibility for evaluating the performance of others should fulfill such responsibility in a fair and considerate manner and on the basis of clearly stated criteria.

3.04 Client Records

- Social workers should take reasonable steps to ensure that documentation in records is accurate and reflects the services provided.

- Social workers should include sufficient and timely documentation in records to facilitate the delivery of services and to ensure continuity of services provided to clients in the future.

- Social workers’ documentation should protect clients’ privacy to the extent that is possible and appropriate and should include only information that is directly relevant to the delivery of services.

- Social workers should store records following the termination of services to ensure reasonable future access. Records should be maintained for the number of years required by state statutes or relevant contracts.

3.05 Billing

Social workers should establish and maintain billing practices that accurately reflect the nature and extent of services provided and that identify who provided the service in the practice setting.

3.06 Client Transfer

- When an individual who is receiving services from another agency or colleague contacts a social worker for services, the social worker should carefully consider the client’s needs before agreeing to provide services. To minimize possible confusion and conflict, social workers should discuss with potential clients the nature of the clients’ current relationship with other service providers and the implications, including possible benefits or risks, of entering into a relationship with a new service provider.

- If a new client has been served by another agency or colleague, social workers should discuss with the client whether consultation with the previous service provider is in the client’s best interest.

3.07 Administration

- Social work administrators should advocate within and outside their agencies for adequate resources to meet clients’ needs.

- Social workers should advocate for resource allocation procedures that are open and fair. When not all clients’ needs can be met, an allocation procedure should be developed that is nondiscriminatory and based on appropriate and consistently applied principles.

- Social workers who are administrators should take reasonable steps to ensure that adequate agency or organizational resources are available to provide appropriate staff supervision.

- Social work administrators should take reasonable steps to ensure that the working environment for which they are responsible is consistent with and encourages compliance with the NASW Code of Ethics. Social work administrators should take reasonable steps to eliminate any conditions in their organizations that violate, interfere with, or discourage compliance with the Code.

3.08 Continuing Education and Staff Development

Social work administrators and supervisors should take reasonable steps to provide or arrange for continuing education and staff development for all staff for whom they are responsible. Continuing education and staff development should address current knowledge and emerging developments related to social work practice and ethics.

3.09 Commitments to Employers

- Social workers generally should adhere to commitments made to employers and employing organizations.

- Social workers should work to improve employing agencies’ policies and procedures and the efficiency and effectiveness of their services.

- Social workers should take reasonable steps to ensure that employers are aware of social workers’ ethical obligations as set forth in the NASW Code of Ethics and of the implications of those obligations for social work practice.

- Social workers should not allow an employing organization’s policies, procedures, regulations, or administrative orders to interfere with their ethical practice of social work. Social workers should take reasonable steps to ensure that their employing organizations’ practices are consistent with the NASW Code of Ethics.

- Social workers should act to prevent and eliminate discrimination in the employing organization’s work assignments and in its employment policies and practices.

- Social workers should accept employment or arrange student field placements only in organizations that exercise fair personnel practices.

- Social workers should be diligent stewards of the resources of their employing organizations, wisely conserving funds where appropriate and never misappropriating funds or using them for unintended purposes.

3.10 Labor¬Management Disputes

- Social workers may engage in organized action, including the formation of and participation in labor unions, to improve services to clients and working conditions.

- The actions of social workers who are involved in labor¬management disputes, job actions, or labor strikes should be guided by the profession’s values, ethical principles, and ethical standards. Reasonable differences of opinion exist among social workers concerning their primary obligation as professionals during an actual or threatened labor strike or job action. Social workers should carefully examine relevant issues and their possible impact on clients before deciding on a course of action.

4. SOCIAL WORKERS’ ETHICAL RESPONSIBILITIES AS PROFESSIONALS

4.01 Competence

- Social workers should accept responsibility or employment only on the basis of existing competence or the intention to acquire the necessary competence.

- Social workers should strive to become and remain proficient in professional practice and the performance of professional functions. Social workers should critically examine and keep current with emerging knowledge relevant to social work. Social workers should routinely review the professional literature and participate in continuing education relevant to social work practice and social work ethics.

- Social workers should base practice on recognized knowledge, including empirically based knowledge, relevant to social work and social work ethics.

4.02 Discrimination

Social workers should not practice, condone, facilitate, or collaborate with any form of discrimination on the basis of race, ethnicity, national origin, color, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity or expression, age, marital status, political belief, religion, immigration status, or mental or physical disability.

4.03 Private Conduct

Social workers should not permit their private conduct to interfere with their ability to fulfill their professional responsibilities.

4.04 Dishonesty, Fraud, and Deception

Social workers should not participate in, condone, or be associated with dishonesty, fraud, or deception. 4.05 Impairment

- Social workers should not allow their own personal problems, psychosocial distress, legal problems, substance abuse, or mental health difficulties to interfere with their professional judgment and performance or to jeopardize the best interests of people for whom they have a professional responsibility.

- Social workers whose personal problems, psychosocial distress, legal problems, substance abuse, or mental health difficulties interfere with their professional judgment and performance should immediately seek consultation and take appropriate remedial action by seeking professional help, making adjustments in workload, terminating practice, or taking any other steps necessary to protect clients and others.

4.06 Misrepresentation

- Social workers should make clear distinctions between statements made and actions engaged in as a private individual and as a representative of the social work profession, a professional social work organization, or the social worker’s employing agency.

- Social workers who speak on behalf of professional social work organizations should accurately represent the official and authorized positions of the organizations.

- Social workers should ensure that their representations to clients, agencies, and the public of professional qualifications, credentials, education, competence, affiliations, services provided, or results to be achieved are accurate. Social workers should claim only those relevant professional credentials they actually possess and take steps to correct any inaccuracies or misrepresentations of their credentials by others.

4.07 Solicitations

- Social workers should not engage in uninvited solicitation of potential clients who, because of their circumstances, are vulnerable to undue influence, manipulation, or coercion.

- Social workers should not engage in solicitation of testimonial endorsements (including solicitation of consent to use a client’s prior statement as a testimonial endorsement) from current clients or from other people who, because of their particular circumstances, are vulnerable to undue influence.

4.08 Acknowledging Credit

- Social workers should take responsibility and credit, including authorship credit, only for work they have actually performed and to which they have contributed.

- Social workers should honestly acknowledge the work of and the contributions made by others.

5. SOCIAL WORKERS’ ETHICAL RESPONSIBILITIES TO THE SOCIAL WORK PROFESSION

5.01 Integrity of the Profession

- Social workers should work toward the maintenance and promotion of high standards of practice.

- Social workers should uphold and advance the values, ethics, knowledge, and mission of the profession. Social workers should protect, enhance, and improve the integrity of the profession through appropriate study and research, active discussion, and responsible criticism of the profession.

- Social workers should contribute time and professional expertise to activities that promote respect for the value, integrity, and competence of the social work profession. These activities may include teaching, research, consultation, service, legislative testimony, presentations in the community, and participation in their professional organizations.

- Social workers should contribute to the knowledge base of social work and share with colleagues their knowledge related to practice, research, and ethics. Social workers should seek to contribute to the profession’s literature and to share their knowledge at professional meetings and conferences.

- Social workers should act to prevent the unauthorized and unqualified practice of social work.

5.02 Evaluation and Research

- Social workers should monitor and evaluate policies, the implementation of programs, and practice interventions.

- Social workers should promote and facilitate evaluation and research to contribute to the development of knowledge.

- Social workers should critically examine and keep current with emerging knowledge relevant to social work and fully use evaluation and research evidence in their professional practice.

- Social workers engaged in evaluation or research should carefully consider possible consequences and should follow guidelines developed for the protection of evaluation and research participants. Appropriate institutional review boards should be consulted.

- Social workers engaged in evaluation or research should obtain voluntary and written informed consent from participants, when appropriate, without any implied or actual deprivation or penalty for refusal to participate; without undue inducement to participate; and with due regard for participants’ well¬being, privacy, and dignity. Informed consent should include information about the nature, extent, and duration of the participation requested and disclosure of the risks and benefits of participation in the research.

- When evaluation or research participants are incapable of giving informed consent, social workers should provide an appropriate explanation to the participants, obtain the participants’ assent to the extent they are able, and obtain written consent from an appropriate proxy.

- Social workers should never design or conduct evaluation or research that does not use consent procedures, such as certain forms of naturalistic observation and archival research, unless rigorous and responsible review of the research has found it to be justified because of its prospective scientific, educational, or applied value and unless equally effective alternative procedures that do not involve waiver of consent are not feasible.

- Social workers should inform participants of their right to withdraw from evaluation and research at any time without penalty.

- Social workers should take appropriate steps to ensure that participants in evaluation and research have access to appropriate supportive services.

- Social workers engaged in evaluation or research should protect participants from unwarranted physical or mental distress, harm, danger, or deprivation.

- Social workers engaged in the evaluation of services should discuss collected information only for professional purposes and only with people professionally concerned with this information.

- Social workers engaged in evaluation or research should ensure the anonymity or confidentiality of participants and of the data obtained from them. Social workers should inform participants of any limits of confidentiality, the measures that will be taken to ensure confidentiality, and when any records containing research data will be destroyed.

- Social workers who report evaluation and research results should protect participants’ confidentiality by omitting identifying information unless proper consent has been obtained authorizing disclosure.

- Social workers should report evaluation and research findings accurately. They should not fabricate or falsify results and should take steps to correct any errors later found in published data using standard publication methods.

- Social workers engaged in evaluation or research should be alert to and avoid conflicts of interest and dual relationships with participants, should inform participants when a real or potential conflict of interest arises, and should take steps to resolve the issue in a manner that makes participants’ interests primary.

- Social workers should educate themselves, their students, and their colleagues about responsible research practices.

6. SOCIAL WORKERS’ ETHICAL RESPONSIBILITIES TO THE BROADER SOCIETY

6.01 Social Welfare

Social workers should promote the general welfare of society, from local to global levels, and the development of people, their communities, and their environments. Social workers should advocate for living conditions conducive to the fulfillment of basic human needs and should promote social, economic, political, and cultural values and institutions that are compatible with the realization of social justice.

6.02 Public Participation

Social workers should facilitate informed participation by the public in shaping social policies and institutions.

6.03 Public Emergencies

Social workers should provide appropriate professional services in public emergencies to the greatest extent possible.

6.04 Social and Political Action

- Social workers should engage in social and political action that seeks to ensure that all people have equal access to the resources, employment, services, and opportunities they require to meet their basic human needs and to develop fully. Social workers should be aware of the impact of the political arena on practice and should advocate for changes in policy and legislation to improve social conditions in order to meet basic human needs and promote social justice.

- Social workers should act to expand choice and opportunity for all people, with special regard for vulnerable, disadvantaged, oppressed, and exploited people and groups.

- Social workers should promote conditions that encourage respect for cultural and social diversity within the United States and globally. Social workers should promote policies and practices that demonstrate respect for difference, support the expansion of cultural knowledge and resources, advocate for programs and institutions that demonstrate cultural competence, and promote policies that safeguard the rights of and confirm equity and social justice for all people.

- Social workers should act to prevent and eliminate domination of, exploitation of, and discrimination against any person, group, or class on the basis of race, ethnicity, national origin, color, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity or expression, age, marital status, political belief, religion, immigration status, or mental or physical disability.

SW 350 - Research in Social Work: Ethical Research

- What is a Scholarly, Peer-Reviewed article?

- Encyclopedias and Dictionaries

- Ethical Research

- Find Journal Articles

- Government Websites

- Social Work Websites

- Writing & Citing

Ethical Codes of Conduct

- NASW Ethical Standards Code of Ethics of the National Association of Social Workers. more... less... "The National Association of Social Workers (NASW) is the largest membership organization of professional social workers in the world, with 132,000 members. NASW works to enhance the professional growth and development of its members, to create and maintain professional standards, and to advance sound social policies."

- JSU Human Subject Review (IRB) Includes policies and procedures along with the "Ethical Research Guidelines for Research Involving Human Participants" quoted from the American Psychologist , June 1981, 637-638.

- Alabama Standards of Professional Conduct and Ethics (for Social Workers)

- Nuremberg Code "The Nuremberg Code has served as a foundation for ethical clinical research since its publication 60 years ago. This landmark document, developed in response to the horrors of human experimentation done by Nazi physicians and investigators, focused crucial attention on the fundamental rights of research participants and on the responsibilities of investigators. It was prepared at a very momentous occasion, following the formal surrender of Germany at the end of the Second World War." Quote taken from: The Nuremberg Code–A critique by Ravindra B. Ghooi

- The Belmont Report "The Belmont Report explains the unifying ethical principles that form the basis for the National Commission’s topic-specific reports and the regulations that incorporate its recommendations. The Belmont Report identifies three fundamental ethical principles for all human subject research – respect for persons, beneficence, and justice. Those principles remain the basis for the HHS human subject protection regulations." more... less... A short video regarding the Belmont Report

- National Research Act of 1974 "TO amend the Public Health Service Act to establish a program of National Research Service Awards to assure the continued excellence of biomedical and behavioral research and to provide for the protection of human subjects involved in biomedical and behavioral research and for other purposes."

- Timeline of Laws Related to the Protection of Human Subjects From the Hippocratic Oath to 2012.

Books on Ethics

Vulnerable Populations

- Special Protections for Children as Research Subjects Rules and Regulations dealing with research on children.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Guidance on various types of vulnerable populations.

Vulnerable Population Books

Informed Consent

- Guide to Informed Consent Guidance for Institutional Review Boards and Clinical Investigators Contents

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Informed Consent Forms and Checklists.

Informed Consent Books

YouTube Videos

- Ethics in Research with Human Participants

- Informed Consent in Research

- Research on Vulnerable Subjects Numerous videos regarding researching vulnerable populations.

- Milgram Obedience Study

- Privacy and Confidentiality in Human Subjects Research

- << Previous: Encyclopedias and Dictionaries

- Next: Find Books >>

- Last Updated: Oct 10, 2024 2:27 PM

- URL: https://libguides.jsu.edu/sw350

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

5.2 Specific ethical issues to consider

Learning objectives.

- Define and describe informed consent

- Identify the unique concerns related to studying vulnerable populations

- Differentiate between anonymity and confidentiality

- Explain the ethical responsibilities of social workers conducting research

As should be clear by now, conducting research on humans presents a number of unique ethical considerations. Human research subjects must be given the opportunity to consent to their participation, after being fully informed of the study’s risks, benefits, and purpose. Further, subjects’ identities and the information they share should be protected by researchers. Of course, the definitions of consent and identity protection may vary by individual researcher, institution, or academic discipline. In section 5.1, we examined the role that institutions play in shaping research ethics. In this section, we’ll look at a few specific topics that individual researchers and social workers must consider before conducting research with human subjects.

Informed consent

All social work research projects involve the voluntary participation of all human subjects. In other words, we cannot force anyone to participate in our research without their knowledge and consent, unlike the experiment in Truman Show . Researchers must therefore design procedures to obtain subjects’ informed consent to participate in their research. Informed consent is defined as a subject’s voluntary agreement to participate in research based on a full understanding of the research and of the possible risks and benefits involved. Although it sounds simple, ensuring that one has actually obtained informed consent is a much more complex process than you might initially presume.

The first requirement to obtain informed consent is that participants may neither waive nor even appear to waive any of their legal rights. In addition, if something were to go wrong during their participation in research, participants cannot release the researcher, the researcher’s sponsor, or any institution from any legal liability (USDHHS, 2009). [1] Unlike biomedical research, for example, social work research does not typically involve asking subjects to place themselves at risk of physical harm. Because of this, social work researchers often do not have to worry about potential liability, however their research may involve other types of risks.

For example, what if a social work researcher fails to sufficiently conceal the identity of a subject who admits to participating in a local swinger’s club? In this case, a violation of confidentiality may negatively affect the participant’s social standing, marriage, custody rights, or employment. Social work research may also involve asking about intimately personal topics, such as trauma or suicide that may be difficult for participants to discuss. Participants may re-experience traumatic events and symptoms when they participate in your study. Even after fully informing the participants of all risks before they consent to the research process, there is the possibility of raising difficult topics that prove overwhelming for participants. In cases like these, it is important for a social work researcher to have a plan to provide supports, such as referrals to community counseling or even calling the police if the participant is a danger to themselves or others.

It is vital that social work researchers craft their consent forms to fully explain their mandatory reporting duties and ensure that subjects understand the terms before participating. Researchers should also emphasize to participants that they can stop the research process at any time or decide to withdraw from the research study for any reason. Importantly, it is not the job of the social work researcher to act as a clinician to the participant. While a supportive role is certainly appropriate for someone experiencing a mental health crisis, social workers must ethically avoid dual roles. Referring a participant in crisis to other mental health professionals who may be better able to help them is preferred.

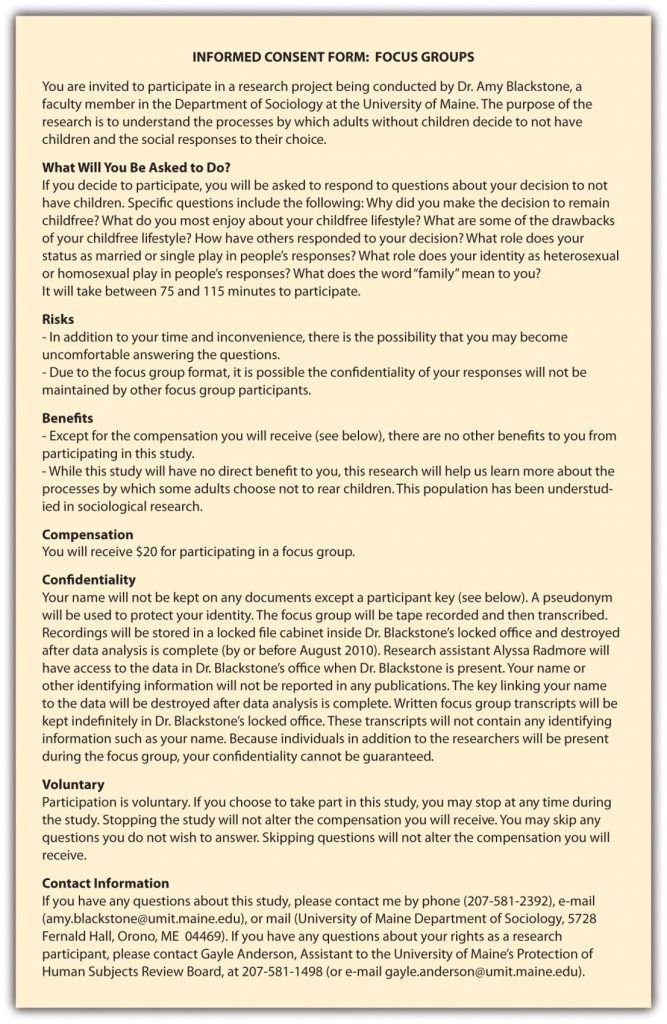

In addition to legal issues, most IRBs are also concerned with details of the research, including: the purpose of the study, possible benefits of participation, and most importantly, potential risks of participation. Further, researchers must describe how they will protect subjects’ identities, all details regarding data collection and storage, and provide a contact reached for additional information about the study and the subjects’ rights. All of this information is typically shared in an informed consent form that researchers provide to subjects. In some cases, subjects are asked to sign the consent form indicating that they have read it and fully understand its contents. In other cases, subjects are simply provided a copy of the consent form and researchers are responsible for making sure that subjects have read and understand the form before proceeding with any kind of data collection. Figure 5.1 showcases a sample informed consent form taken from a research project on child-free adults. Note that this consent form describes a risk that may be unique to the particular method of data collection being employed: focus groups.

When preparing to obtain informed consent, it is important to consider that not all potential research subjects are considered equally competent or legally allowed to consent to participate in research. Subjects from vulnerable populations may be at risk of experiencing undue influence or coercion. [3] The rules for consent are more stringent for vulnerable populations. For example, minors must have the consent of a legal guardian in order to participate in research. In some cases, the minors themselves are also asked to participate in the consent process by signing special, age-appropriate consent forms. Vulnerable populations raise many unique concerns because they may not be able to fully consent to research participation. Researchers must be concerned with the potential for underrepresentation of vulnerable groups in studies. On one hand, researchers must ensure that their procedures to obtain consent are not coercive, as the informed consent process can be more rigorous for these groups. On the other hand, researchers must also work to ensure members of vulnerable populations are not excluded from participation simply because of their vulnerability or the complexity of obtaining their consent. While there is no easy solution to this double-edged sword, an awareness of the potential concerns associated with research on vulnerable populations is important for identifying whatever solution is most appropriate for a specific case.

Protection of identities

As mentioned earlier, the informed consent process requires researchers to outline how they will protect the identities of subjects. This aspect of the process, however, is one of the most commonly misunderstood aspects of research.

In protecting subjects’ identities, researchers typically promise to maintain either the anonymity or confidentiality of their research subjects. Anonymity is the more stringent of the two. When a researcher promises anonymity to participants, not even the researcher is able to link participants’ data with their identities. Anonymity may be impossible for some social work researchers to promise because several of the modes of data collection that social workers employ. Face-to-face interviewing means that subjects will be visible to researchers and will hold a conversation, making anonymity impossible. In other cases, the researcher may have a signed consent form or obtain personal information on a survey and will therefore know the identities of their research participants. In these cases, a researcher should be able to at least promise confidentiality to participants.

Offering confidentiality means that some of the subjects’ identifying information is known and may be kept, but only the researcher can link identity to data with the promise to keep this information private. Confidentiality in research and clinical practice are similar in that you know who your clients are, but others do not, and you promise to keep their information and identity private. As you can see under the “Risks” section of the consent form in Figure 5.1, sometimes it is not even possible to promise that a subject’s confidentiality will be maintained. This is the case if data collection takes place in public or in the presence of other research participants, like in a focus group study. Social workers also cannot promise confidentiality in cases where research participants pose an imminent danger to themselves or others, or if they disclose abuse of children or other vulnerable populations. These situations fall under a social worker’s duty to report, which requires the researcher to prioritize their legal obligations over participant confidentiality.

Protecting research participants’ identities is not always a simple prospect, especially for those conducting research on stigmatized groups or illegal behaviors. Sociologist Scott DeMuth learned how difficult this task was while conducting his dissertation research on a group of animal rights activists. As a participant observer, DeMuth knew the identities of his research subjects. When some of his research subjects vandalized facilities and removed animals from several research labs at the University of Iowa, a grand jury called on Mr. DeMuth to reveal the identities of the participants in the raid. When DeMuth refused to do so, he was jailed briefly and then charged with conspiracy to commit animal enterprise terrorism and cause damage to the animal enterprise (Jaschik, 2009). [4]

Publicly, DeMuth’s case raised many of the same questions as Laud Humphreys’ work 40 years earlier. What do social scientists owe the public? By protecting his research subjects, is Mr. DeMuth harming those whose labs were vandalized? Is he harming the taxpayers who funded those labs, or is it more important that he emphasize the promise of confidentiality to his research participants? DeMuth’s case also sparked controversy among academics, some of whom thought that as an academic himself, DeMuth should have been more sympathetic to the plight of the faculty and students who lost years of research as a result of the attack on their labs. Many others stood by DeMuth, arguing that the personal and academic freedom of scholars must be protected whether we support their research topics and subjects or not. DeMuth’s academic adviser even created a new group, Scholars for Academic Justice ( http://sajumn.wordpress.com ), to support DeMuth and other academics who face persecution or prosecution as a result of the research they conduct. What do you think? Should DeMuth have revealed the identities of his research subjects? Why or why not?

Disciplinary considerations

Often times, specific disciplines will provide their own set of guidelines for protecting research subjects and, more generally, for conducting ethical research. For social workers, the National Association of Social Workers (NASW) Code of Ethics section 5.02 describes the responsibilities of social workers in conducting research. Summarized below, these guidelines outline that as a representative of the social work profession, it is your responsibility to conduct to conduct and use research in an ethical manner.

A social worker should:

- Monitor and evaluate policies, programs, and practice interventions

- Contribute to the development of knowledge through research

- Keep current with the best available research evidence to inform practice

- Ensure voluntary and fully informed consent of all participants

- Avoid engaging in any deception in the research process

- Allow participants to withdraw from the study at any time

- Provide access for participants to appropriate supportive services

- Protect research participants from harm

- Maintain confidentiality

- Report findings accurately

- Disclose any conflicts of interest

Key Takeaways

- Researchers must obtain the informed consent of the people who participate in their research.

- Social workers must take steps to minimize the harms that could arise during the research process.

- If a researcher promises anonymity, they cannot link individual participants with their data.

- If a researcher promises confidentiality, they promise not to reveal the identities of research participants, even though they can link individual participants with their data.

- The NASW Code of Ethics includes specific responsibilities for social work researchers.

Anonymity – the identity of research participants is not known to researchers

Confidentiality – identifying information about research participants is known to the researchers but is not divulged to anyone else

Informed consent – a research subject’s voluntary agreement to participate in a study based on a full understanding of the study and of the possible risks and benefits involved

Image attributions

consent by Catkin CC-0

Anonymous by kalhh CC-0

- US Department of Health and Human Services. (2009). Code of federal regulations (45 CFR 46). The full set of requirements for informed consent can be read at https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/regulations-and-policy/regulations/45-cfr-46/index.html ↵

- Figure 5.1 is copied from Blackstone, A. (2012) Principles of sociological inquiry: Qualitative and quantitative methods. Saylor Foundation. Retrieved from: https://saylordotorg.github.io/text_principles-of-sociological-inquiry-qualitative-and-quantitative-methods/ Shared under CC-BY-NC-SA 3.0 License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/) ↵

- The US Department of Health and Human Services’ guidelines on vulnerable populations can be read at https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/regulations-and-policy/guidance/vulnerable-populations/index.html. ↵

- Jaschik, S. (2009, December 4). Protecting his sources. Inside Higher Ed . Retrieved from: http://www.insidehighered.com/news/2009/12/04/demuth ↵

Scientific Inquiry in Social Work Copyright © 2018 by Matthew DeCarlo is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

The NASW Code of Ethics is a set of standards that guide the professional conduct of social workers. The 2021 update includes language that addresses the importance of professional self-care. Moreover, revisions to Cultural Competence standard provide more explicit guidance to social workers.

This is the first comprehensive, in-depth examination of the code of ethics of the social work profession. Ethical Standards in Social Work provides guidance for practice in areas such as confidentiality, boundary issues, informed consent, conflicts of interest, research and evaluation, and more.

Addressing the implicit ethics of research, Guillemin and Gillam (Citation 2004) delineate three relevant subtypes: procedural ethics (seeking approval from a relevant ethics committee to undertake research), ethics in practice (the everyday ethical issues that arise in doing the research), and research ethics (as articulated in professional ...

The purpose of this article is to propose a set of practice standards on social justice and research, building on existing provisions in social work codes of ethics and providing specific...

The Code socializes practitioners new to the field to social work’s mission, values, ethical principles, and ethical standards. The Code articulates standards that the social work profession itself can use to assess whether social workers have engaged in unethical conduct.

The current NASW Code of Ethics reflects major changes in social work’s approach to ethical issues throughout its history and the profession’s increasingly mature grasp of ethical issues. During the earliest years of social work’s history, few formal ethical standards existed.

Highlights. Newly added standard 5.02 (f) offers more concrete guidance for social workers using technology in their research and evaluation. This guidance includes the consideration of informed consent and research participants’ access to the technology and availability of alternatives.

Part I: INTRODUCTION TO ETHICAL DECISION MAKING. 1. Ethical Choices in the Helping Professions. 2. Values and Professional Ethics. 3. Guidelines for Ethical Decision Making: Concepts, Approaches and Values. 4. Guidelines for Ethical Decision Making: The Decision Making Process and Tools. Part II: ETHICAL DILEMMAS IN PROFESSIONAL PRACTICE. 5.

Learning Objectives. Define and describe informed consent. Identify the unique concerns related to studying vulnerable populations. Differentiate between anonymity and confidentiality. Explain the ethical responsibilities of social workers conducting research.

In addition to the values and standards that influence social work research, unique considerations emerge for scholars of any discipline who elect to study certain populations, settings and problems.