Department of History

Religion in context.

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction

The essence of religion and the context of religious beliefs, practices, and institutions

Subjectivity in the study of religion, neutrality in the study of religion.

- Early attempts to study religion

- Later attempts to study religion

- Theories of the Middle Ages

- Theories of the Renaissance and Reformation

- The late 17th and 18th centuries

- The early 19th century

- Historical and literary studies

- Archaeological studies

- Theories concerning the origins of religion

- Functional and structural studies of religion

- Specialized studies

- Theories of stages

- Comparative studies

- Other sociological studies

- Psychological studies

- Psychoanalytical studies

- Other studies

- The concerns of the philosophy of religion

- Theories of Schleiermacher and Hegel

- Empiricism and pragmatism

- Modern existentialist and phenomenological studies

- Relationship between Western and non-Western philosophy in regard to religion

- Historical-critical studies

- Neo-orthodoxy and demythologization

- The relationship of Western Christianity to other religions

- Modern origin and development of the history and phenomenology of religion

- The Chicago school

- Other studies and emphases

- Interdisciplinary perspective

- Cross-cultural perspective

study of religion

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- Table Of Contents

study of religion , attempt to understand the various aspects of religion , especially through the use of other intellectual disciplines .

The study of religion emerged as a formal discipline during the 19th century, when the methods and approaches of history , philology , literary criticism , psychology , anthropology , sociology , economics , and other fields were brought to bear on the task of determining the history, origins, and functions of religion. No consensus among scholars concerning the best way to study religion has developed, however. One of the many reasons for this failure is that each discipline enlisted to study religion has its own distinctive methods and topics, and scholars often disagree about how to resolve the inevitable conflicts between these different intellectual perspectives. Another reason is that questions about the origins and functions of religion have often been conflated with questions about the truth of religion, and this has led to controversies that tend to hinder the development of common concepts, methodologies , and problems.

Nature and significance

Even a commonly accepted definition of religion has proved difficult to establish, though not for lack of trying. Attempts have been made to find a distinctive ingredient in all religions, such as the numinous, or spiritual, experience, the contrast between the sacred and the profane, and the belief in one or more gods. But objections have been brought against all these attempts, either because the rich variety of religions makes it easy to find counterexamples or because the element cited as central is in some religions peripheral . The gods play a merely subsidiary role, for example, in most phases of Theravada (“Way of the Elders”) Buddhism . A more promising method would seem to be that of exhibiting aspects of religion that are typical of religions, though not necessarily universal, such as the occurrence of the rituals of worship . There are religions, however, in which even worship rituals are not central. Thus, the preliminary task of the student of religion must be to amass an inventory of kinds of religious phenomena.

Even if an inventory of kinds of belief and practice could be gathered so as to provide a typical profile of what counts as religion, some scholars would maintain that the differences between religions are more significant than their similarities. Moreover, in the absence of a tight definition there will always be a number of disputed cases. Thus, some political ideologies , such as communism and fascism , have been regarded as analogous to religion. Certain attempts at a functionalist definition of religion, such as that of the German American theologian Paul Tillich (1886–1965), who defined religion in terms of human beings’ ultimate concern, would leave the way open to count these ideologies as proper objects of the study of religion (Tillich himself called them quasi-religions). Although there is still no agreement on this issue, the frontier between traditional religions and modern political ideologies remains a promising topic of study.

Neutrality and subjectivity in the study of religion

Discussion about religion has been complicated further by the attempt of some Christian theologians, notably Karl Barth (1886–1968), to draw a distinction between religion and the Gospel (the proclamation peculiar to Christianity). This distinction depends to some extent upon taking a projectionist view of religion as a human product. This tradition goes back in modern times to the seminal work of the German philosopher Ludwig Feuerbach (1804–72), who proposed that God was the extension of human aspirations , and it is found in the work of the philosopher Karl Marx , the founder of psychoanalysis Sigmund Freud , and others. Barth’s distinction attempts to draw a line between the transcendent , as it reveals itself to humans, and religion, as a human product involved in the response to revelation . The difficulty of the distinction consists chiefly in a denial that God, as the object of the response, is a “religious” being (i.e., God is transcendent, not religious in the sense of being a part of the human product), and the question about revelation as a religious fact thus needs to be answered.

There are doubts about how far there can be neutrality and objectivity in the study of religion. Is it possible to understand a faith without holding it? If it is not possible, then cross-religious comparisons would mostly break down, for normally it is not possible to be inside more than one religion. But it is necessary to be clear about what objectivity and subjectivity in religion mean. Religion can be said to be subjective in at least two senses. First, the practice of religion involves inner experiences and sentiments , such as feelings of God guiding the life of the devotee. Here religion involves subjectivity in the sense of individual experience. Religion may also be thought to be subjective because the criteria by which its truth is decided are obscure and hard to come by, so there is no obvious “objective” test, the way in which there is for a large range of empirical claims in the physical world. As to the first sense, one of the challenges to the student of religion is the problem of evoking its inner, individual side, which is not observable in any straightforward way. In considering a religion, however, the scholar is concerned not only with individual responses but also with communal ones. Often the scholar is confronted only with texts describing beliefs and stories, so the inner sentiments that these both evoke and express must be inferred. The adherent of a faith is no doubt authoritative as to his own experience, but what of the communal significance of the rites and institutions in which the adherent participates? Thus, the matter of coming to understand the inner side of a religion involves a dialectic between participant observation and dialogical (interpersonal) relationship with the adherents of the other faith.

The other sense of the subjectivity of religion is properly a matter for theology and the philosophy of religion . The study of religion can roughly be divided between descriptive and historical inquiries on the one hand and normative inquiries on the other. Normative inquiries primarily concern the truth of religious claims, the acceptability of religious values, and other such normative aspects; descriptive inquiries, which are only indirectly involved with the normative elements of religion, are primarily concerned with the history, structure, and other observable elements of religion. The distinction, however, is not an absolute one, for, as has been noted, descriptions of religion may sometimes incorporate theories about religion that imply something about the truth or other normative aspects of some or all religions. Conversely, theological claims may imply something about the history of a religion. The dominant sense in which the contemporary study of religion is understood is the descriptive sense.

The attempt simply to describe and not judge religious beliefs and practices is often considered to involve epochē —that is, the suspension of belief and the “bracketing” of the phenomena under investigation. The idea of epochē is borrowed from the philosophy of the German thinker Edmund Husserl (1859–1938), the father of phenomenology , and the procedure is regarded as central to the phenomenology of religion .

The term phenomenology refers first to the attempt to describe religious phenomena in a way that brings out the beliefs and attitudes of the adherents of the religion under investigation but without either endorsing or rejecting the beliefs and attitudes. Thus, the “bracketing” means forgetting about beliefs of one’s own that might endorse or conflict with what is being investigated. The term phenomenology also refers to the attempt to devise a typology, or classification, of religious phenomena—religious activities, beliefs, and institutions.

To some extent the emphasis on neutral description arises in modern times as a reaction to “committed” accounts of religion, which were for long the norm and which still exist among those who treat religion from a theological point of view. The Christian theologian, for example, may see a particular historical process as providential. This is a legitimate perspective from the standpoint of faith. But the historical process itself has to be investigated “scientifically”—that is, by considering the evidence, using the techniques of historical enquiry and other scientific methods. Conflict sometimes arises because the committed point of view is likely to begin from a more conservative stance, accepting at face value the scriptural accounts of events, whereas the “secular” historian may be more skeptical, especially of records of miraculous events. The study of religion may thus come to have a reflexive effect on religion itself, such as the manner in which modern Christian theology has been profoundly affected by the whole question of the historicity of the New Testament .

The reflexive effect of the study of religion on religion itself may in practice make it more difficult for the student of religion to adopt the detachment required by bracketing. Scholars do generally agree that the pursuit of objectivity is desirable, provided this stance does not involve the sacrifice of a sense of the inner aspect of religion. The stress on the distinction between the descriptive and normative approaches is becoming more frequent among scholars of religion.

Religion in the Ancient World

Religion (from the Latin Religio , meaning 'restraint,' or Relegere , according to Cicero , meaning 'to repeat, to read again,' or, most likely, Religionem , 'to show respect for what is sacred') is an organized system of beliefs and practices revolving around, or leading to, a transcendent spiritual experience. There is no culture in human history that has not practiced some form of religion.

In ancient times, religion was indistinguishable from what is known as ' mythology ' in the present day and consisted of regular rituals based on a belief in higher supernatural entities who created and continued to maintain the world and surrounding cosmos. These entities were anthropomorphic and behaved in ways which mirrored the values of the culture closely (as in Egypt ) or sometimes engaged in acts antithetical to those values (as one sees with the gods of Greece ).

Religion, then and now, concerns itself with the spiritual aspect of the human condition, gods and goddesses (or a single personal god or goddess), the creation of the world, a human being's place in the world, life after death , eternity, and how to escape from suffering in this world or in the next; and every nation has created its own god in its own image and resemblance. The Greek philosopher Xenophanes of Colophon (l. c. 570-478 BCE) writes:

Mortals suppose that the gods are born and have clothes and voices and shapes like their own. But if oxen, horses and lions had hands or could paint with their hands and fashion works as men do, horses would paint horse-like images of gods and oxen oxen-like ones, and each would fashion bodies like their own. The Ethiopians consider the gods flat-nosed and black; the Thracians blue-eyed and red-haired. (Diogenes Laertius, Lives )

Xenophanes believed there was "one god, among gods and men the greatest, not at all like mortals in body or mind" but he was in the minority. Monotheism did not make sense to the ancient people aside from the visionaries and prophets of Judaism . Most people, at least as far as can be discerned from the written and archaeological record, believed in many gods, each of whom had a special sphere of influence. In one's personal life there is not just one other person who provides for one's needs; one interacts with many different kinds of people in order to achieve wholeness and maintain a living.

In the course of one's life in the present day, one will interact with one's parents, siblings, teachers, friends, lovers, employers, doctors, gas station attendants, plumbers, politicians, veterinarians, and so on. No one single person can fill all these roles or supply all of an individual's needs – just as it was in ancient times.

In this same way, the ancient people felt that no single god could possibly take care of all the needs of an individual. Just as one would not go to a plumber with one's sick dog, one would not go to a god of war with a problem concerning love. If one were suffering heartbreak, one went to the goddess of love; if one wanted to win at combat, only then would one consult the god of war.

The many gods of the religions of the ancient world fulfilled this function as specialists in their respective areas. In some cultures, a certain god or goddess would become so popular that he or she would transcend the cultural understanding of multiplicity and assume a position so powerful and all-encompassing as to almost transform a polytheistic culture to henotheistic.

While polytheism means the worship of many gods, henotheism means the worship of one god in many forms. This shift in understanding was extremely rare in the ancient world, and the goddess Isis and god Amun of Egypt are probably the best examples of the complete ascendancy of a deity from one-among-many to the supreme creator and sustainer of the universe recognized in different forms.

As noted, every ancient culture practiced some form of religion, but where religion began cannot be pinpointed with any certainty. The argument over whether Mesopotamian religion inspired that of the Egyptians has gone on for over a century now and is no closer to being resolved than when it began. It is most probable that every culture developed its own belief in supernatural entities to explain natural phenomena (day and night, the seasons ) or to help make sense of their lives and the uncertain state humans find themselves in daily.

While it may be an interesting exercise in cultural exchange to attempt tracing the origins of religion, it does not seem a very worthwhile use of one's time when it seems fairly clear that the religious impulse is simply a part of the human condition and different cultures in different parts of the world could have come to the same conclusions about the meaning of life independently.

Religion in Ancient Mesopotamia

As with many cultural advancements and inventions, the 'cradle of civilization ' Mesopotamia has been cited as the birthplace of religion. When religion developed in Mesopotamia is unknown, but the first written records of religious practice date to c. 3500 BCE from Sumer . Mesopotamian religious beliefs held that human beings were co-workers with the gods and labored with them and for them to hold back the forces of chaos which had been checked by the supreme deities at the beginning of time. Order was created out of chaos by the gods and one of the most popular myths illustrating this principle told of the great god Marduk who defeated Tiamat and the forces of chaos to create the world. Historian D. Brendan Nagle writes:

Despite the gods' apparent victory, there was no guarantee that the forces of chaos might not recover their strength and overturn the orderly creation of the gods. Gods and humans alike were involved in the perpetual struggle to restrain the powers of chaos, and they each had their own role to play in this dramatic battle . The responsibility of the dwellers of Mesopotamian cities was to provide the gods with everything they needed to run the world. (11)

Humans were created, in fact, for this very purpose: to work with and for the gods toward a mutually beneficial end. The claim of some historians that the Mesopotamians were slaves to their gods is untenable because it is quite clear that the people understood their position as co-workers. The gods repaid humans for their service by taking care of their daily needs in life (such as supplying them with beer , the drink of the gods) and maintaining the world in which they lived. These gods intimately knew the needs of the people because they were not distant entities who lived in the heavens but dwelt in homes on earth built for them by their people; these homes were the temples which were raised in every Mesopotamian city .

Temple complexes, dominated by the towering ziggurat , were considered the literal homes of the gods and their statues were fed, bathed, and clothed daily as the priests and priestesses cared for them as one would a king or queen. In the case of Marduk, for example, his statue was carried out of his temple during the festival honoring him and through the city of Babylon so that he could appreciate its beauty while enjoying the fresh air and sunshine.

Inanna was another powerful deity who was greatly revered as the goddess of love, sex, and war, and whose priests and priestesses cared for her statue and temple faithfully. Inanna is considered one of the earliest examples of the dying-and-reviving god figure who goes down into the underworld and returns to life, bringing fertility and abundance to the land. She was so popular her worship spread across all of Mesopotamia from the southern region of Sumer. She became Ishtar of the Akkadians (and later the Assyrians), Astarte of the Phoenicians , Sauska of the Hurrians - Hittites , and was associated with Aphrodite of the Greeks, Isis of the Egyptians, and Venus of the Romans.

The temples were the center of the city's life throughout Mesopotamian history from the Akkadian Empire (c. 2334-2150 BCE) to the Assyrian (c. 1900-612 BCE) and afterwards. The temple served in multiple capacities: the clergy dispensed grain and surplus goods to the poor, counseled those in need, provided medical services, and sponsored the grand festivals which honored the gods. Although the gods took great care of humans while they lived, the Mesopotamian afterlife was a dreary underworld, located beneath the far mountains, where souls drank stale water from puddles and ate dust for eternity in the 'land of no return.' This bleak view of their eternal home was markedly different from that of the Egyptians as well as of their neighbors the Persians.

Ancient Persian Religion

The early religion of the Persians arrived on the Iranian Plateau with the migrations of the Aryans (properly understood as Indo-Iranians) some time prior to the third millennium BCE. The early faith was polytheistic with a supreme god, Ahura Mazda , presiding over lesser deities. Among the most popular of these was Atar (god of fire), Mithra (god of the rising sun and covenants), Hvar Khshsata (god of the full sun), and Anahita (goddess of fertility, water, health and healing, and wisdom). These gods stood for the forces of goodness and order against the evil spirits of disorder and chaos.

At some point between 1500-1000 BCE, the prophet and visionary Zoroaster (also given as Zarathustra ) claimed a revelation from Ahura Mazda through which he understood that this god was the one supreme being, creator of the universe, and maintainer of order, who needed no other gods beside him. Zoroasters's vision would become the religion of Zoroastrianism – one of the oldest in the world still practiced in the present day.

According to this belief, the purpose of human life is to choose between following Ahura Mazda and the way of truth and order ( Asha ) or following his eternal adversary, Angra Mainyu (also given as Ahriman ) and the path of lies and chaos ( Druj ). Humans were considered inherently good and possessing of free will to choose between these two paths; whichever one a person chose would inform that person's life and their destination after death. When a person died, they crossed the Chinvat Bridge where they were judged.

Sign up for our free weekly email newsletter!

Those who had lived a good life in accordance with the precepts of Ahura Mazda were rewarded by continued life in the paradise of the House of Song, while those who had allowed themselves to be deceived by Angra Mainyu were dropped into the hell of the House of Lies ( druj-demana ) where they were tortured relentlessly and, even though surrounded by other suffering souls, would feel eternally alone.

Although scholars often characterize Zoroastrianism as a dualistic religion, it seems clear Zoroaster founded a monotheistic faith focused on an all-powerful single deity. The dualistic aspects of the religion appeared later in the so-called heresy of Zorvanism which made Ahura Mazda and Angra Mainyu brothers, the sons of Zorvan (time) and time itself became the supreme power through which all things came into being and passed away.

Zoroastrianism also held that a messiah would come at some future date (known as the Saoshyant – One Who Brings Benefit) to redeem humanity in an event known as the Frashokereti which was the end of time and brought reunion with Ahura Mazda. These concepts would influence the later religions of Judaism, Christianity , and Islam . The belief in a single god, unlike human beings and all-powerful, may have also influenced Egyptian religion during the Amarna Period in which the pharaoh Akhenaten (r. 1353-1336 BCE) abolished traditional Egyptian rituals and practices and replaced them with a monotheistic system focused on the one god Aten.

Religion in Egypt

Egyptian religion was similar to Mesopotamian belief, however, in that human beings were co-workers with the gods to maintain order. The principle of harmony (known to the Egyptians as ma'at ) was of the highest importance in Egyptian life (and in the afterlife), and their religion was fully integrated into every aspect of existence. Egyptian religion was a combination of magic, mythology, science , medicine , psychiatry, spiritualism, herbology, as well as the modern understanding of 'religion' as belief in a higher power and a life after death. The gods were the friends of human beings and sought only the best for them by providing them with the most perfect of all lands to live in and an eternal home to enjoy when their lives on earth were done.

This belief system would continue, with various developments, throughout Egypt's long history, only interrupted by Akhenaten's religious reforms during his reign. After his death, the old religion was restored by his son and successor Tutankhamun (r. c. 1336 to c. 1327 BCE) who reopened the temples and revived the ancient rituals and customs.

The first written records of Egyptian religious practice come from around 3400 BCE in the Predynastic Period in Egypt (c. 6000 to c. 3150 BCE). Deities such as Isis, Osiris , Ptah, Hathor , Atum, Set, Nephthys , and Horus were already established as potent forces to be recognized fairly early on. The Egyptian Creation Myth is similar to the beginning of the Mesopotamian story in that originally there was only chaotic, slow-swirling waters. This ocean was without bounds, depthless, and silent until, upon its surface, there rose a hill of earth (known as the ben-ben , the primordial mound, which, it is thought, the pyramids symbolize) and the great god Atum (the sun) stood upon the ben-ben and spoke, giving birth to the god Shu (of the air), the goddess Tefnut (of moisture), the god Geb (of earth), and the goddess Nut (of sky). Alongside Atum stood Heka , the personification of magic, and magic ( heka ) gave birth to the universe.

Atum had intended Nut as his bride but she fell in love with Geb. Angry with the lovers, Atum separated them by stretching Nut across the sky high away from Geb on the earth. Although the lovers were separated during the day, they came together at night and Nut bore three sons, Osiris, Set, and Horus, and two daughters, Isis and Nephthys.

Osiris, as eldest, was announced as 'Lord of all the Earth' when he was born and was given his sister Isis as a wife. Set, consumed by jealousy, hated his brother and killed him to assume the throne. Isis then embalmed her husband's body and, with powerful charms, resurrected Osiris who returned from the dead to bring life to the people of Egypt. Osiris later served as the Supreme Judge of the souls of the dead in the Hall of Truth and, by weighing the heart of the soul in the balances, decided who was granted eternal life.

The Egyptian afterlife was known as the Field of Reeds and was a mirror-image of life on earth down to one's favorite tree and stream and dog. Those that one loved in life would either be waiting when one arrived or would follow after. The Egyptians viewed earthly existence as simply one part of an eternal journey and were so concerned about passing easily to the next phase that they created their elaborate tombs (the pyramids), temples, and funerary inscriptions (the Pyramid Texts , Coffin Texts , and The Egyptian Book of the Dead ) to help the soul's passage from this world to the next.

The gods cared for one after death just as they had in life from the beginning of time. The goddess Qebhet brought water to the thirsty souls in the land of the dead and other goddesses such as Serket and Nephthys cared for and protected the souls as they journeyed to the Field of Reeds. An ancient Egyptian understood that, from birth to death and even after death, the universe had been ordered by the gods and everyone had a place in that order.

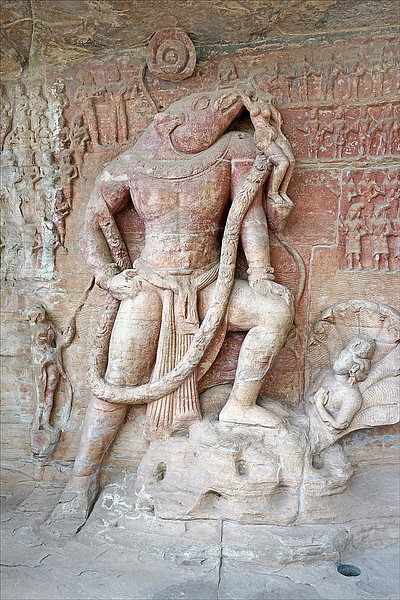

Religion in China & India

This principle of order is also paramount in the world's oldest religion still being practiced today: Hinduism (known to adherents as Sanatan Dharma , 'Eternal Order', thought to have been founded as early as 5500 BCE but certainly by c. 2300 BCE). Although often viewed as a polytheistic faith, Hinduism is actually henotheistic. There is only one supreme god in Hinduism, Brahma , and all other deities are his aspects and reflections. Since Brahma is too immense a concept for the human mind to comprehend, he presents himself in the many different versions of himself which people recognize as deities such as Vishnu , Shiva , and the many others. The Hindu belief system includes 330 million gods and these range from those who are known at a national level (such as Krishna ) to lesser-known local deities.

The primary understanding of Hinduism is that there is an order to the universe and every individual has a specific place in that order. Each person on the planet has a duty ( dharma ) which only they can perform. If one acts rightly ( karma ) in the performance of that duty, then one is rewarded by moving closer to the supreme being and eventually becoming one with god; if one does not, then one is reincarnated as many times as it takes to finally understand how to live and draw closer to union with the supreme soul.

This belief was carried over by Siddhartha Gautama when he became the Buddha and founded the religion known as Buddhism . In Buddhism, however, one is not seeking union with a god but with one's higher nature as one leaves behind the illusions of the world which generate suffering and cloud the mind with the fear of loss and death. Buddhism became so popular that it traveled from India to China where it enjoyed equal success.

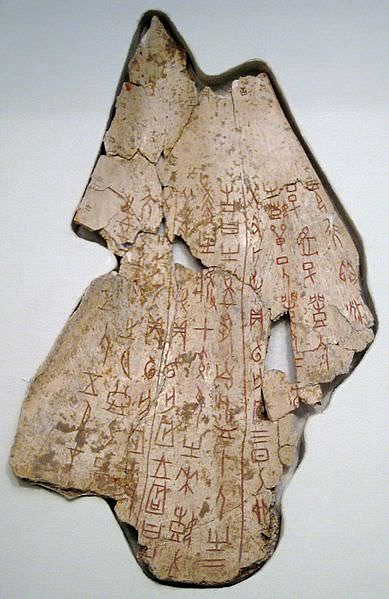

In ancient China, religion is thought to have developed as early as c. 4500 BCE as evidenced by designs on ceramics found at the Neolithic site of Banpo Village . This early belief structure may have been a mix of animism and mythology as these images include recognizable animals and pig-dragons, precursors to the famous Chinese dragon.

By the time of the Xia Dynasty (2070-1600 BCE), there were many anthropomorphic gods worshiped with a chief god, Shangti, presiding over all. This belief continued, with modifications, during the period of the Shang Dynasty (1600-1046 BCE) which developed the practice of ancestor worship.

The people believed that Shangti had so many responsibilities that he had become too busy to handle their needs. It was thought that when a person died, they went to live with the gods and became intermediaries between the people and those gods. Ancestor worship influenced the two great Chinese belief systems of Confucianism and Taoism , both of which made ancestor worship core tenets of their practices. In time, Shangti was replaced with the concept of Tian (heaven), a paradise where the dead would reside eternally in peace.

In order to pass from one's earthly life into heaven, one had to cross the bridge of forgetfulness over an abyss and, after looking back on one's life for the last time, drink from a cup which purged all memory. At the bridge, one was either judged worthy of heaven – and so passed on – or unworthy – and slipped from the bridge into the abyss to be swallowed up in hell. Other versions of this same scenario claim the soul was reincarnated after drinking from the cup. Either way, the living were expected to remember the dead who had passed over the bridge to the other side and to honor their memory.

Religion in Mesoamerica

Remembrance of the dead and the part they still play in the lives of those on earth was an important component of all ancient religions, including the belief system of the Maya . The gods were involved in every aspect of the life of the Maya. As with other cultures, there were many different deities (over 250), all of whom had their own special sphere of influence. They controlled the weather, the harvest, they dictated one's mate, presided over every birth, and were present at one's death.

The Mayan afterlife was similar to the Mesopotamian in that it was a dark and dreary place, but the Maya imagined an even worse fate where one was constantly under threat of attack or deception by the demon lords who inhabited the underworld (known as Xibalba or Metnal). The dread of the journey through Xibalba was such a potent cultural force that the Maya are the only known ancient culture to honor a goddess of suicide (Ixtab) because suicides were thought to bypass Xibalba and go straight to paradise (as did those who died in childbirth or in battle). The Maya believed in the cyclical nature of life, that all things which seem to die simply are transformed, and considered human life just another part of the kind of pattern they saw all around them in nature. They felt death was a natural progression after life and feared the very unnatural possibility that the dead could return to haunt the living.

It was possible that a person would hang on to life for any of a number of reasons (the chief being improper burial ), and so ceremonies were performed to remember the dead and honor their spirit. This belief was also held by Mesoamerican cultures other than the Maya such as the Aztec and Tarascan. In time, it developed into the holiday known today as The Day of the Dead ( El Dia de los Muertos ), in which people celebrate the lives of those who have passed on and remember their names.

It was not only people who were to be remembered and honored, however, but also a very important deity scholars refer to as the Maize God. The Maize God is a dying-and-reviving god figure in the form of Hun Hunahpu who was killed by the Lords of Xibalba, brought back to life by his sons, the Hero Twins, and emerges from the underworld as corn. The 'Tonsured' Maize God or 'Foliated' Maize God are common images found in Maya iconography. He is always pictured as eternally young and handsome with an elongated head like a corncob, long, flowing hair like corn silk , and ornamented with jade to symbolize the corn stalk. He was considered so important by the Maya that mothers would bind the heads of their young sons to flatten the forehead and elongate their heads to resemble him.

The Maize God remained an important deity to the Maya even when eclipsed by the greatest and most popular of the gods Gucumatz (also known as Kukulcan and Quetzalcoatl ) whose great pyramid at Chichen Itza is still visited by millions of people every year in the present day. On the twin equinoxes of every year, the sun casts a shadow on the stairs of the pyramid structure which seems to resemble a great serpent descending from the top to the bottom; this is thought to be the great Kukulcan returning from the heavens to earth to impart his blessings. Even today, people gather at Chichen Itza to witness this event at the equinoxes and to remember the past and hope for the future.

Greek & Roman Religion

The importance of remembrance of the dead as part of one's religious devotions was integral to the beliefs of the Greeks as well. Continued remembrance of the dead by the living kept the soul of the deceased alive in the afterlife. The Greeks, like the other cultures mentioned, believed in many gods who often cared for their human charges but, just as often, pursued their own pleasure.

The capricious nature of the gods may have contributed to the development of philosophy in Greece as philosophy can only develop in a culture where religion is not providing for the people's spiritual needs. Plato consistently criticized the Greek concept of the gods and Critias claimed they were simply created by men to control other men. Xenophanes, as noted above, claimed the Greek view was completely wrong and God was unimaginable.

Still, to the majority of the Greeks – and central to the function of society – the gods were to be honored and so were those who had passed over into their realm. Just because a person was no longer living on earth did not mean that person was to be forgotten any more than one would forget to honor the invisible gods. As with other ancient cultures, religion in Greece was fully integrated into one's daily life and routine.

The Greeks consulted the gods on matters ranging from affairs of state to personal decisions regarding love, marriage, or one's job. An ancient story tells of how the writer Xenophon (430 to c. 354 BCE) went to Socrates asking whether the philosopher thought he should join the army of Cyrus the Younger on campaign to Persia . Socrates sent him to ask the question of the god at Delphi . Instead of asking his original question, Xenophon asked the god of Delphi which of the many gods was best to court favor with to ensure a successful venture and safe return. He appears to have gotten the correct answer since he survived the disastrous campaign of Cyrus and not only returned to Athens but saved the bulk of the army.

The religion of Rome followed the same paradigm as that of Greece. The Roman religion most likely began as a kind of animism and developed as they came into contact with other cultures. The Greeks had the most significant impact on Roman religion, and many of the Roman gods are simply Greek deities with Roman names and slightly altered attributes.

In Rome, the worship of the gods was intimately tied to affairs of state and the stability of the society was thought to rest on how well the people revered the gods and participated in the rituals which honored them. The Vestal Virgins are one famous example of this belief in that these women were counted on to maintain the vows they had taken and perform their duties responsibly in order to continually honor Vesta and all the goddess gave to the people.

Although the Romans had imported their primary gods from Greece, once the Roman religion was established and linked to the welfare of the state, no foreign gods were welcomed. When worship of the popular Egyptian goddess Isis was brought to Rome, Emperor Augustus forbade any temples to be built in her honor or public rites observed in her worship because he felt such attention paid to a foreign deity would undermine the authority of the government and established religious beliefs. To the Romans, the gods had created everything according to their will and maintained the universe in the best way possible and a human being was obligated to show them honor for their gifts.

This was true not only for the 'major' gods of the Roman pantheon but also for the spirits of the home. The penates were earth spirits of the pantry who kept one's home safe and harmonious. One was expected to be thankful for their efforts and remember them upon entering or leaving one's house. Statues of the penates were taken out of the cupboard and set on the table during meals to honor them, and sacrifices were left by the hearth for their enjoyment. If one were diligent in appreciating their efforts, one was rewarded with continued health and happiness and, if one forgot them, one suffered for such ingratitude. Although the religions of other cultures did not have precisely these same kinds of spirits, the recognition of spirits of place – and especially the home – was common.

Common Themes in Ancient Religion & Their Continuance

The religions of the ancient world shared many of the same patterns with each other even though the cultures may never have had any contact with each other. The spiritual iconography of the Mayan and Egyptian pyramids has been recognized since the Maya were first brought to the world's attention by John Lloyd Stephens and Frederick Catherwood in the 19th century, but the actual belief structures, stories, and most significant figures in ancient mythology are remarkably similar from culture to culture.

In every culture, one finds the same or very similar patterns, which the people found resonant and which gave vitality to their beliefs. These patterns include the existence of many gods who take a personal interest in the lives of people; creation by a supernatural entity who speaks it, fashions it, or commands it into existence; other supernatural beings emanating from the first and greatest one; a supernatural explanation for the creation of the earth and human beings; a relationship between the created humans and their creator god requiring worship and sacrifice.

There is also the repetition of the figure known as the Dying and Reviving God, often a powerful entity himself, who is killed or dies and comes back to life for the good of his people: Osiris in Egypt, Krishna in India, the Maize God in Mesoamerica, Bacchus in Rome, Attis in Greece, Tammuz in Mesopotamia. There is often an afterlife similar to an earthly existence (Egypt and Greece), antithetical to life on earth (Mesoamerica and Mesopotamia), or a combination of both (China and India).

The resonant spiritual message of these different religions is repeated in texts from Phoenicia (2700 BCE) to Sumer (2100 BCE) to Palestine (1440 BCE) to Greece (800 BCE) to Rome (c. 100 CE) and went on to inform the beliefs of those who came later. This motif is even touched on in Judaism in the figure of Joseph (Genesis 37, 39-45) who is sold by his brothers into slavery in Egypt, goes down into prison following the accusations of Potiphar's wife, and is later released and restored. Although he does not actually die, after his symbolic 'resurrection' he saves the country from famine, providing for the people in the same way as other regenerative figures.

The Phoenician tale of the great god Baal who dies and returns to life to battle the chaos of the god Yamm was already old in 2750 BCE when the city of Tyre was founded (according to Herodotus ) and the Greek story of the dying-and-reviving god Adonis (c. 600 BCE) was derived from earlier Phoenician tales based on Tammuz which was borrowed by the Sumerians (and later the Persians) in the famous Descent of Inanna myth.

This theme of life-after-death and life coming from death and, of course, the judgment after death, gained the greatest fame through the evangelical efforts of St. Paul who spread the word of the dying-and-reviving god Jesus Christ throughout ancient Palestine, Asia Minor , Greece, and Rome (c. 42-62). Paul's vision of the figure of Jesus , the anointed son of God who dies to redeem humanity, was drawn from the earlier belief systems and informed the understanding of the scribes who would write the books which make up the Bible .

The religion of Christianity made standard a belief in an afterlife and set up an organized set of rituals by which an adherent could gain everlasting life. In so doing, the early Christians were simply following in the footsteps of the Sumerians, the Egyptians, the Phoenicians, the Greeks, and the Romans all of whom had their own stylized rituals for the worship of their gods.

After the Christians, the Muslim interpreters of the Koran instituted their own rituals for understanding the supreme deity which, though vastly different in form from those of Christianity, Judaism or any of the older 'pagan' religions, served the same purpose as the rituals once practiced in worship of the Egyptian pantheon over 5,000 years ago: to provide human beings with the understanding that they are not alone in their struggles, suffering, and triumphs, that they can restrain their baser urges, and that death is not the end of existence. The religions of the ancient world provided answers to people's questions about life and death and, in this regard, are no different than those faiths practiced in the world today.

Subscribe to topic Related Content Books Cite This Work License

Bibliography

- Baird, F. E. & Kaufmann, W. Philosophic Classics Volume I: Ancient Philosophy. Prentice Hall, 2007.

- Bauer, S.W. The History of the Ancient World. W. W. Norton & Company, 2007.

- Black, J. Gods, Demons and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia. University of Texas Press, 1992.

- Bulfinch, T. Bulfinch's Mythology. Public Domain Books, 2009.

- Diogenes Laertius & Yonge, C. D. Lives of the Eminent Philosophers. Oxford University Press, 2012.

- Ghosts in the Ancient World by Joshua J. Mark , accessed 15 May 2020.

- Greek Religion by Mark Cartwright , accessed 15 May 2020.

- Koller, J.M. Asian Philosophies. Routledge, 2004.

- Nagle, D. B. The Ancient World: A Social and Cultural History. Pearson, 2009.

- Nardo, D. Egyptian Mythology. Enslow Publishers, 2001.

- Nardo, D. Exploring Cultural History - Living in Ancient Rome. Greenhaven Press, 2003.

- Pinch, G. Egyptian Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Goddesses, and Traditions of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press, 2004.

- Plato. The Collected Dialogues of Plato. Princeton University Press, 2005.

- Roman Household Spirits by Joshua J. Mark , accessed 15 May 2020.

- Smith, H. The World's Religions. Harper One Publishers, 2009.

- Stuart, G.E. The Mysterious Maya. National Geographic Society, 1977.

About the Author

Translations

We want people all over the world to learn about history. Help us and translate this definition into another language!

Questions & Answers

What is the oldest religion in the world, where does the word religion come from and what does it mean, is zoroastrianism still practiced today, what is the most popular or widely practiced religion in the world, related content.

Parthian Religion

Free for the world, supported by you.

World History Encyclopedia is a non-profit organization. For only $5 per month you can become a member and support our mission to engage people with cultural heritage and to improve history education worldwide.

In this age of AI and fake news, access to accurate information is crucial. Every month our fact-checked encyclopedia enables millions of people all around the globe to learn about history, for free. Please support free history education for only $5 per month!

External Links

Cite this work.

Mark, J. J. (2018, March 23). Religion in the Ancient World . World History Encyclopedia . Retrieved from https://www.worldhistory.org/religion/

Chicago Style

Mark, Joshua J.. " Religion in the Ancient World ." World History Encyclopedia . Last modified March 23, 2018. https://www.worldhistory.org/religion/.

Mark, Joshua J.. " Religion in the Ancient World ." World History Encyclopedia . World History Encyclopedia, 23 Mar 2018. Web. 15 Oct 2024.

License & Copyright

Submitted by Joshua J. Mark , published on 23 March 2018. The copyright holder has published this content under the following license: Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike . This license lets others remix, tweak, and build upon this content non-commercially, as long as they credit the author and license their new creations under the identical terms. When republishing on the web a hyperlink back to the original content source URL must be included. Please note that content linked from this page may have different licensing terms.

IMAGES

VIDEO