Javascript is disabled

- We are changing

- Accessible screenings

- Sound and Vision

- Objects and stories

- Researchers

- Access to our collection

- Research help

- Research directory

- Donate an object

- Science Museum Group Journal

- Press office

- Support the museum

- Volunteering

- Corporate sponsorship

National Science and Media Museum Bradford BD1 1NQ

The museum and IMAX cinema are temporarily closed. Pictureville and Cubby Broccoli cinemas are open.

Find out about our major transformation .

A very short history of cinema

Published: 18 June 2020

Learn about the history and development of cinema, from the Kinetoscope in 1891 to today’s 3D revival.

Cinematography is the illusion of movement by the recording and subsequent rapid projection of many still photographic pictures on a screen. Originally a product of 19th-century scientific endeavour, cinema has become a medium of mass entertainment and communication, and today it is a multi-billion-pound industry.

Who invented cinema?

No one person invented cinema. However, in 1891 the Edison Company successfully demonstrated a prototype of the Kinetoscope , which enabled one person at a time to view moving pictures.

The first public Kinetoscope demonstration took place in 1893. By 1894 the Kinetoscope was a commercial success, with public parlours established around the world.

The first to present projected moving pictures to a paying audience were the Lumière brothers in December 1895 in Paris, France. They used a device of their own making, the Cinématographe, which was a camera, a projector and a film printer all in one.

What were early films like?

At first, films were very short, sometimes only a few minutes or less. They were shown at fairgrounds, music halls, or anywhere a screen could be set up and a room darkened. Subjects included local scenes and activities, views of foreign lands, short comedies and newsworthy events.

The films were accompanied by lectures, music and a lot of audience participation. Although they did not have synchronised dialogue, they were not ‘silent’ as they are sometimes described.

The rise of the film industry

By 1914, several national film industries were established. At this time, Europe, Russia and Scandinavia were the dominant industries; America was much less important. Films became longer and storytelling, or narrative, became the dominant form.

As more people paid to see movies, the industry which grew around them was prepared to invest more money in their production, distribution and exhibition, so large studios were established and dedicated cinemas built. The First World War greatly affected the film industry in Europe, and the American industry grew in relative importance.

The first 30 years of cinema were characterised by the growth and consolidation of an industrial base, the establishment of the narrative form, and refinement of technology.

Adding colour

Colour was first added to black-and-white movies through hand colouring, tinting, toning and stencilling.

By 1906, the principles of colour separation were used to produce so-called ‘natural colour’ moving images with the British Kinemacolor process, first presented to the public in 1909.

Kinemacolor was primarily used for documentary (or ‘actuality’) films, such as the epic With Our King and Queen Through India (also known as The Delhi Durbar ) of 1912, which ran for over 2 hours in total.

The early Technicolor processes from 1915 onwards were cumbersome and expensive, and colour was not used more widely until the introduction of its three‑colour process in 1932. It was used for films such as Gone With the Wind and The Wizard of Oz (both 1939) in Hollywood and A Matter of Life and Death (1946) in the UK.

Frames of stencil colour film

Advertisement for With Our King and Queen Through India , 1912

Adding sound

The first attempts to add synchronised sound to projected pictures used phonographic cylinders or discs.

The first feature-length movie incorporating synchronised dialogue, The Jazz Singer (USA, 1927), used the Warner Brothers’ Vitaphone system, which employed a separate record disc with each reel of film for the sound.

This system proved unreliable and was soon replaced by an optical, variable density soundtrack recorded photographically along the edge of the film, developed originally for newsreels such as Movietone.

Cinema’s Golden Age

By the early 1930s, nearly all feature-length movies were presented with synchronised sound and, by the mid-1930s, some were in full colour too. The advent of sound secured the dominant role of the American industry and gave rise to the so-called ‘Golden Age of Hollywood’.

During the 1930s and 1940s, cinema was the principal form of popular entertainment, with people often attending cinemas twice a week. Ornate ’super’ cinemas or ‘picture palaces’, offering extra facilities such as cafés and ballrooms, came to towns and cities; many of them could hold over 3,000 people in a single auditorium.

In Britain, the highest attendances occurred in 1946, with over 31 million visits to the cinema each week.

What is the aspect ratio?

Thomas Edison had used perforated 35mm film in the Kinetoscope, and in 1909 this was adopted as the worldwide industry standard. The picture had a width-to-height relationship—known as the aspect ratio—of 4:3 or 1.33:1. The first number refers to the width of the screen, and the second to the height. So for example, for every 4 centimetres in width, there will be 3 in height.

With the advent of optical sound, the aspect ratio was adjusted to 1.37:1. This is known as the ‘Academy ratio’, as it was officially approved by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (the Oscars people) in 1932.

Although there were many experiments with other formats, there were no major changes in screen ratios until the 1950s.

How did cinema compete with television?

The introduction of television in America prompted a number of technical experiments designed to maintain public interest in cinema.

In 1952, the Cinerama process, using three projectors and a wide, deeply curved screen together with multi-track surround sound, was premiered. It had a very large aspect ratio of 2.59:1, giving audiences a greater sense of immersion, and proved extremely popular.

However, Cinerama was technically complex and therefore expensive to produce and show. Widescreen cinema was not widely adopted by the industry until the invention of CinemaScope in 1953 and Todd‑AO in 1955. Both processes used single projectors in their presentation.

CinemaScope ‘squeezed’ images on 35mm film; when projected, they were expanded laterally by the projector lens to fit the screen. Todd-AO used film with a width of 70mm. By the end of the 1950s, these innovations had effectively changed the shape of the cinema screen, with aspect ratios of either 2.35:1 or 1.66:1 becoming standard. Stereo sound, which had been experimented with in the 1940s, also became part of the new widescreen experience.

Specialist large-screen systems using 70mm film were also developed. The most successful of these has been IMAX, which as of 2020 has over 1,500 screens around the world. For many years IMAX cinemas have shown films specially made in its unique 2D or 3D formats but more recently they have shown popular mainstream feature films which have been digitally re-mastered in the IMAX format, often with additional scenes or 3D effects.

How have cinema attendance figures changed?

While cinemas had some success in fighting the competition of television, they never regained the position and influence they held in the 1930s and 40s, and over the next 30 years audiences dwindled. By 1984 cinema attendances in Britain had declined to one million a week.

By the late 2000s, however, that number had trebled. The first British multiplex was built in Milton Keynes in 1985, sparking a boom in out-of-town multiplex cinemas.

Today, most people see films on television, whether terrestrial, satellite or subscription video on demand (SVOD) services. Streaming film content on computers, tablets and mobile phones is becoming more common as it proves to be more convenient for modern audiences and lifestyles.

Although America still appears to be the most influential film industry, the reality is more complex. Many films are produced internationally—either made in various countries or financed by multinational companies that have interests across a range of media.

What’s next?

In the past 20 years, film production has been profoundly altered by the impact of rapidly improving digital technology. Most mainstream productions are now shot on digital formats with subsequent processes, such as editing and special effects, undertaken on computers.

Cinemas have invested in digital projection facilities capable of producing screen images that rival the sharpness, detail and brightness of traditional film projection. Only a small number of more specialist cinemas have retained film projection equipment.

In the past few years there has been a revival of interest in 3D features, sparked by the availability of digital technology. Whether this will be more than a short-term phenomenon (as previous attempts at 3D in the 1950s and 1980s had been) remains to be seen, though the trend towards 3D production has seen greater investment and industry commitment than before.

Further reading

- Cinematography in the Science Museum Group collection

- The Lumière Brothers: Pioneers of cinema and colour photography , National Science and Media Museum blog

- Cinerama in the UK: The history of 3-strip cinema in Pictureville Cinema , National Science and Media Museum blog

- BFI Filmography—a complete history of UK feature film

- BFI National Archive

- Imperial War Museums film archive

Pictureville Cinema

Pictureville is the home of cinema at the National Science and Media Museum, showing everything from blockbusters to indie gems.

Robert Paul and the race to invent cinema

Discover the story of Robert Paul, the forgotten pioneer whose innovations earned him the title of ‘father of the British film industry’.

Cinema technology

Discover objects from our collection which illuminate the technological development of moving pictures.

- Part of the Science Museum Group

- Terms and conditions

- Privacy and cookies

- Modern Slavery Statement

- Web accessibility

The History of Film Timeline — All Eras of Film History Explained

M otion pictures have enticed and inspired artists, audiences, and critics for more than a century. Today, we’re going to explore the history of film by looking at the major movements that have defined cinema worldwide. We’re also going to explore the technical craft of filmmaking from the persistence of vision to colorization to synchronous sound. By the end, you’ll know all the broad strokes in the history of film.

Note: this article doesn’t cover every piece of film history. Some minor movements and technical breakthroughs have been left out – check out the StudioBinder blog for more content.

- Pre-Film: Photographic Techniques and Motion Picture Theory

- The Nascent Film Era (1870s-1910): The First Motion Pictures

- The First Film Movements: Dadaism, German Expressionism, and Soviet Montage Theory

- Manifest Destiny and the End of the Silent Era

- Hollywood Epics and the Pre-Code Era

- The Early Golden Age and the Introduction of Color

- Wartime Film and Cinematic Propaganda

- Post-War Film Movements: French New Wave, Italian Neorealism, Scandinavian Revival, and Bengali Cinema

- The Golden Age of Hollywood: The Studio System and Censorship

- New Hollywood: The Emergence of Global Blockbuster Cinema

- Dogme 95 and the Independent Movement

- New Methods of Cinematic Distribution and the Current State of Film

When Were Movies Invented?

Pre-film techniques and theory.

Movies refer to moving pictures and moving pictures can be traced all the way back to prehistoric times. Have you ever made a shadow puppet show? If you have, then you’ve made a moving picture.

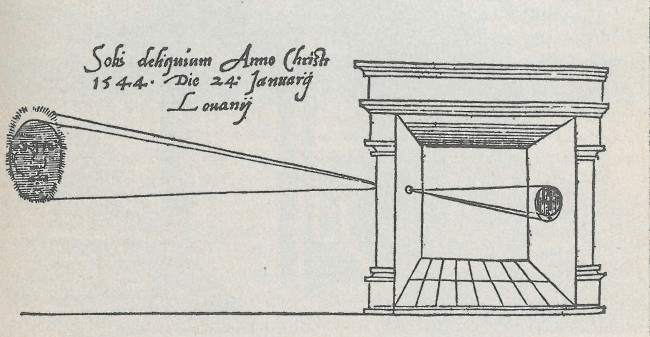

To create a moving picture with your hands is one thing, to utilize a device is another. The camera obscura (believed to have been circulated in the fifth century BCE) is perhaps the oldest photographic device in existence. The camera obscura is a device that’s used to reproduce images by reflecting light through a small peephole.

Here’s a picture of one from Gemma Frisius’ 1545 book De Radio Astronomica et Geometrica :

When Did Movies Start? • Camera Obscura in ‘De Radio Astronomica et Geometrica’

Through the camera obscura, we can trace the principles of filmmaking back thousands of years. But despite the technical achievement of the camera obscura, it took many of those years to develop the technology needed to capture moving images then later display them.

When Was Film Invented?

The first motion pictures.

When were movies invented ? The first motion pictures were incredibly simple – usually just a few frames of people or animals. Eadweard Muybridge’s The Horse in Motion is perhaps the most famous of these early motion pictures. In 1878, Muybridge set up a racing track with 24 cameras to photograph whether horses gallop with all four hooves off the ground at any time

The result was sensational. Muybridge’s pictures set the stage for all coming films; check out a short video on Muybridge and his work below.

When Did the First Movie Come Out? • Eadweard Muybridge’s ‘The Horse in Motion’ by San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

Muybridge’s job wasn’t done after taking the photographs though; he still had to produce a projection machine to display them. So, Muybridge built a device called the zoopraxiscope, which was regarded as a breakthrough device for motion picture projecting.

Muybridge’s films (and tech) inspired Thomas Edison to study motion picture theory and develop his own camera equipment.

Films as we know them today emerged globally around the turn of the century, circa 1900. Much of that development can be attributed to the works of the Lumière Brothers, who together pioneered the technical craft of moviemaking with their cinematograph projection machine. The Lumière Brothers’ 1895 shorts are regarded as the first commercial films of all-time; though not technically true (remember Muybridge’s work).

French actor and illusionist Georges Méliès attempted to buy a cinematograph from the Lumière Brothers in 1895, but was denied. So, Méliès ventured elsewhere; eventually finding a partner in Englishman Robert W. Paul.

Over the following years, Méliès learned just about everything there was to know about movies and projection machines. Here’s a video on Méliès’ master of film and the illusory arts from Crash Course Film History.

When Were Movies Invented? • Georges Méliès – Master of Illusion by Crash Course

Méliès’ shorts The One Man Band (1900) and A Trip to the Moon (1902) are considered two of the most trailblazing films in all of film history. Over the course of his career, Méliès produced over 500 films. His contemporary mastery of visual effects , multiple exposure , and cinematography made him one of the greatest filmmakers of all-time .

Movie History

The first film movements.

War and cinema go together like two peas in a pod. As we continue on through our analysis of the history of film, you’ll start to notice that just about every major movement sprouted in the wake of war. First, the movements that sprouted in response to World War I:

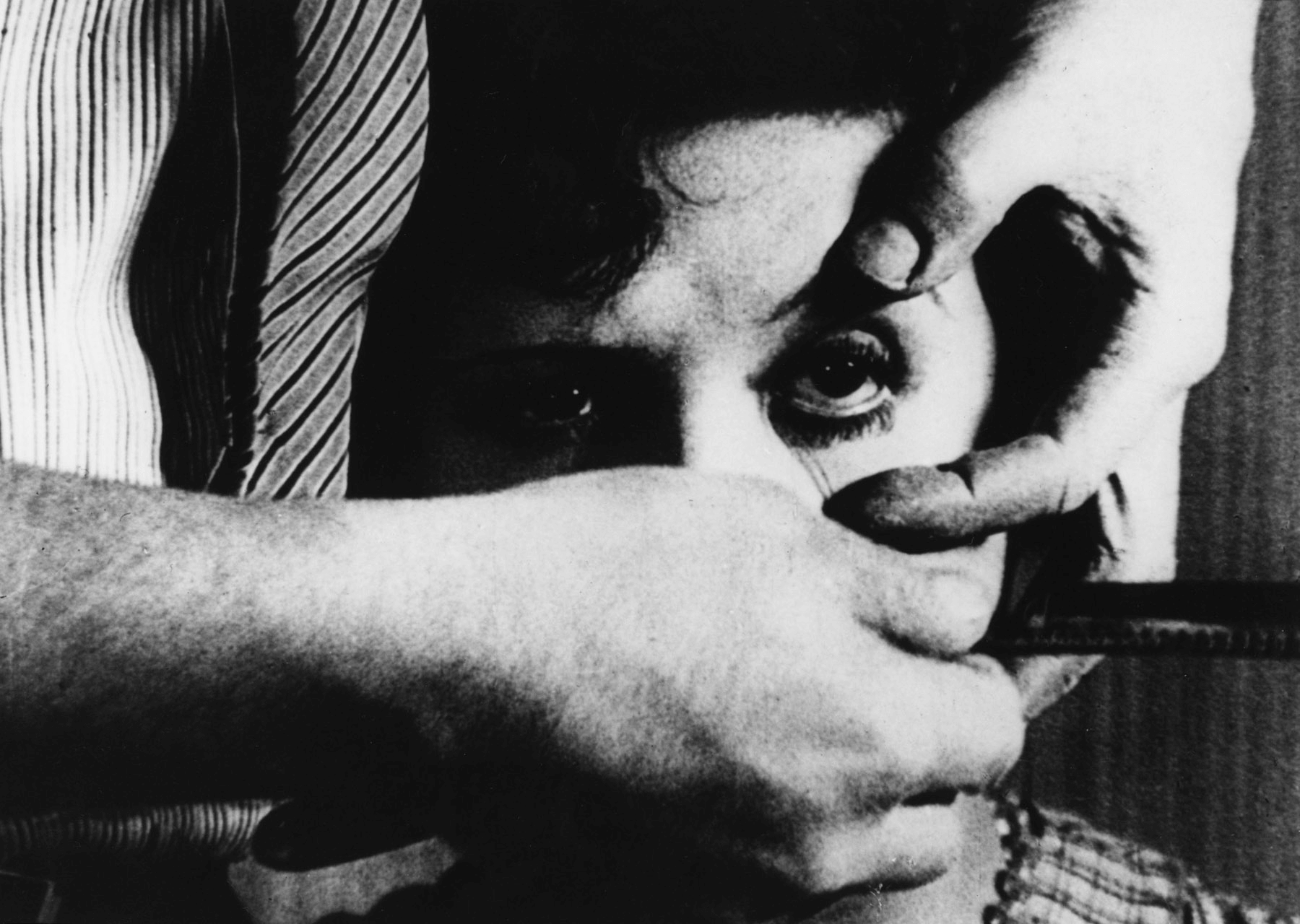

DADAISM AND SURREALISM

History of Motion Pictures • Still From ‘Un Chien Andalou’ by Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dalí

Major Dadaist filmmakers: Luis Buñuel, Salvador Dalí, Germaine Dulac.

Major Dadaist films: Return to Reason (1923), The Seashell and the Clergyman (1928), U n Chien Andalou (1929).

Dadaism – an art movement that began in Zurich, Switzerland during World War I (1915) – rejected authority; effectively laying the groundwork for surrealist cinema .

Dadaism may have begun in Zurich circa 1915, but it didn’t take off until years later in Paris, France. By 1920, the people of France had expressed a growing disillusionment with the country’s government and economy. Sound familiar?

That’s because they’re the same points of conflict that incited the French Revolution. But this time around, the French people revolted in a different way: with art. And not just any art: bonkers, crazy, absurd, anti-this, anti-that art.

It’s important to note that Paris wasn’t the only place where dadaist art was being created. But it was the place where most of the dadaist, surrealist film was being created. We’ll get to dadaist film in a short bit, but first, let’s review a quick video on Dada art from Curious Muse.

Where Did Film Originate? • Dadaism in 8 Minutes by Curious Muse

Salvador Dalí, Germaine Dulac, and Luis Buñuel were some of the forefront faces of the surrealist film movement of the 1920s. French filmmakers, such as Jean Epstein and Jean Renoir experimented with surrealist films during this era as well.

Dalí and Buñuel’s 1929 film Un Chien Andalou is undoubtedly one of the most influential surrealist/dadaist films. Let’s check out a clip:

History of Movies • ‘Un Chien Andalou’ Clip

The influence of Un Chien Andalou on surrealist cinema can’t be quantified; key similarities can be seen between the film and the works of Walt Disney, David Lynch , Terry Gilliam , and other surrealist directors.

Learn more about surrealism in film →

GERMAN EXPRESSIONISM

The Creation of Film and German Expressionism • Still From ‘The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari’ by Robert Wiene

- German Expressionism – an art movement defined by monumentalist structures and ideas – began before World War I but didn’t take off in popularity until after the war, much like the Dadaist movement.

- Major German Expressionist filmmakers: Fritz Lang, F.W. Murnau, Robert Wiene

- Major German Expressionist films: The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920), Nosferatu (1922), and Metropolis (1927).

German Expressionism changed everything for the “look” and “feel” of cinema. When you think of German Expressionism, think contrast, gothic, dark, brooding imagery and colored filters. Here’s a quick video on the German Expressionist movement from Crash Course:

History of Film Timeline • German Expressionism Explained

The great works of the German Expressionist movement are some of the earliest movies I consider accessible to modern audiences. Perhaps no German Expressionist film proves this point better than Fritz Lang’s M ; which was the ultimate culmination of the movement’s stylistic tenets. Check out the trailer for M below.

Most Important Film in History of German Expressionism • ‘M’ (1931) Trailer, Restored by BFI

M not only epitomized the “monster” tone of the German Expressionist era, it set the stage for all future psychological thrillers. The film also pioneered sound engineering in film through the clever use of diegetic and non-diegetic sound . Fun fact: it was also one of the first movies to incorporate a leitmotif as part of its soundtrack.

Over time, the stylistic flourishes of the German Expressionist movement gave way to new voices – but its influence lived on in monster-horror and chiaroscuro lighting techniques.

Learn more about German Expressionism →

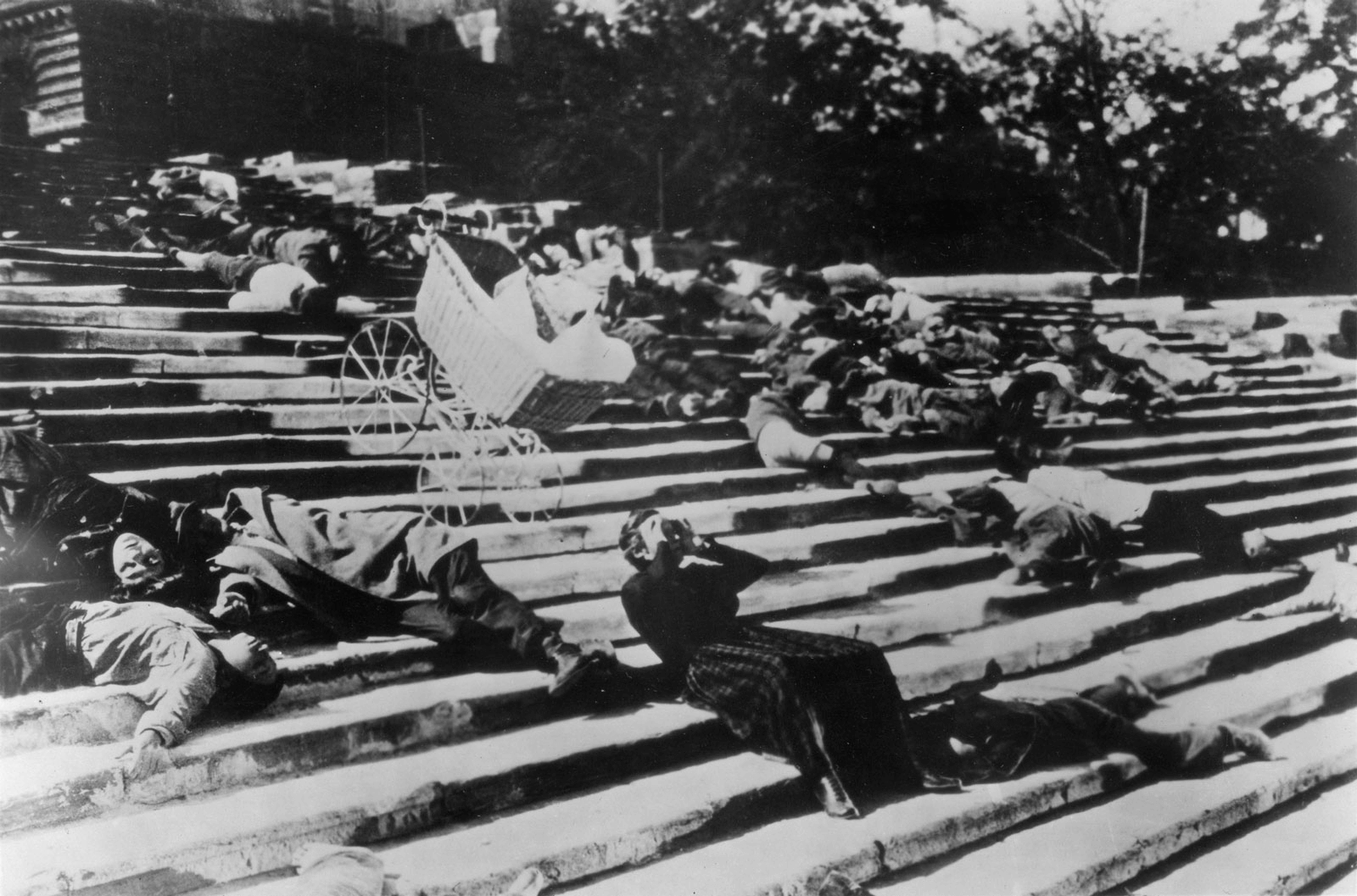

SOVIET MONTAGE THEORY

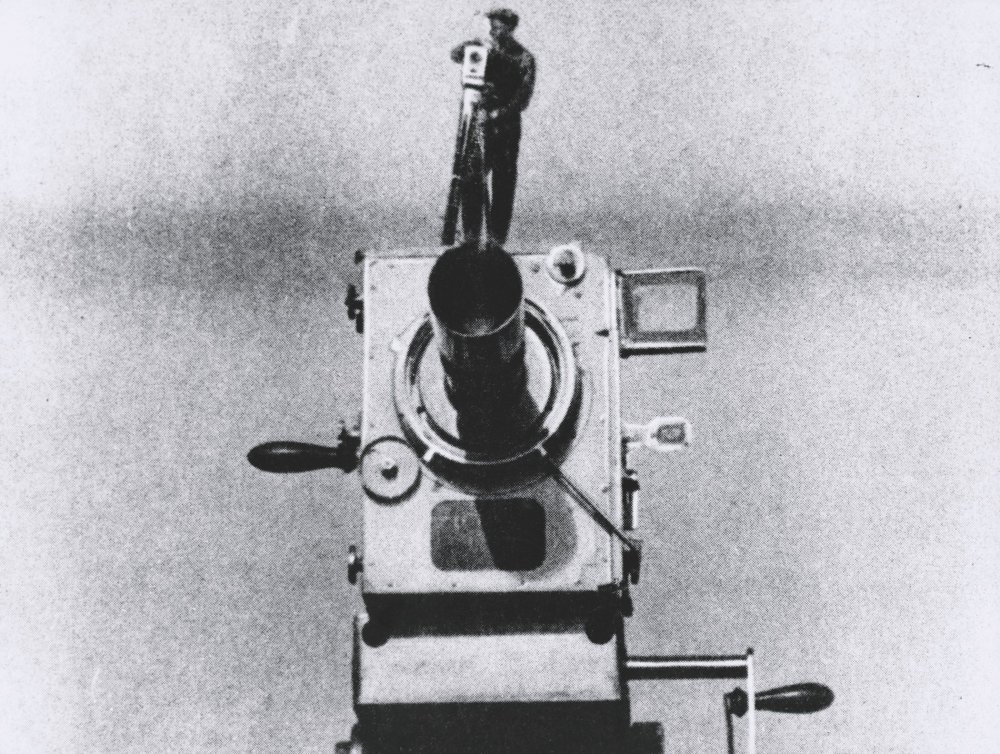

Film History 101 • The Odessa Steps in ‘Battleship Potemkin’

- Soviet Montage Theory – a Soviet Russian film movement that helped establish the principles of film editing – took place from the 1910s to the 1930s.

- Major Soviet Montage Theory filmmakers: Lev Kuleshov, Sergei Eisenstein , Dziga Vertov.

- Major Soviet Montage Theory films: Kino-Eye (1924), Battleship Potemkin (1925), Man With a Movie Camera (1929).

Soviet Montage Theory was a deconstructionist film movement, so as to say it wasn’t as interested in making movies as it was taking movies apart… or seeing how they worked. That being said, Soviet Montage Theory did produce some classics.

Here’s a video on Soviet Montage Theory from Filmmaker IQ:

Eras of Movies • The History of Cutting in Soviet Montage Theory by Filmmaker IQ

The Bolshevik government set-up a film school called VGIK (the Gerasimov Institute of Cinematography) after the Russian Revolution. The practitioners of Soviet Montage Theory were the OG members of the “film school generation;” Kuleshov and Eisenstein were their teachers.

Battleship Potemkin was the most noteworthy film to come out of the Soviet Montage Theory movement. Check out an awesome analysis from One Hundred Years of Cinema below.

History of Film Summary • How Sergei Eisenstein Used Montage to Film the Unfilmable by One Hundred Years of Cinema

Soviet Montage Theory begged filmmakers to arrange, deconstruct, and rearrange film clips to better communicate emotional associations to audiences. The legacy of Soviet Montage Theory lives on in the form of the Kuleshov effect and contemporary montages .

Learn more about Soviet Montage Theory →

When Did Movies Become Popular?

The end of the silent era.

There was no Hollywood in the early years of American cinema – there was only Thomas Edison’s Motion Picture Patents Company in New Jersey.

Ever wonder why Europe seemed to dominate the early years of film? Well it was because Thomas Edison sued American filmmakers into oblivion. Edison owned a litany of U.S. patents on camera tech – and he wielded his stamps of ownership with righteous fury. The Edison Manufacturing Company did produce some noteworthy early films – such as 1903’s The Great Train Robbery – but their gaps were few and far between.

To escape Edison’s legal monopoly, filmmakers ventured west, all the way to Southern California.

Fortunate for the nomads: the arid temperature and mountainous terrain of Southern California proved perfect for making movies. By the early 1910s, Hollywood emerged as the working capital of the United States’s movie industry.

Director/actors like Charlie Chaplin , Harold Lloyd and Buster Keaton became stars – but remember, movies were silent, and people knew there would be an acoustic revolution in cinema. Before we move on from the Silent Era, check out this great video from Crash Course.

When Did Movies Become Popular? • The Silent Era by Crash Course

The Silent Era holds an important place in film history – but it was mostly ushered out in 1927 with The Jazz Singer . Al Jolson singing in The Jazz Singer is considered the first time sound ever synchronized with a feature film . Over the next few years, Hollywood cinema exploded in popularity. This short period from 1927-1934 is known as pre-Code Hollywood.

When Did Hollywood Start?

Pre-code hollywood.

In our previous section, we touched on the rise of Hollywood, but not the Hollywood epic. The Hollywood epic, which we regard as longer in duration and wider in scope than the average movie, set the stage for blockbuster cinema. So, let’s quickly touch on the history of Hollywood epics before jumping into pre-code Hollywood.

It’s impossible to talk about Hollywood epics without bringing up D.W. Griffith. Griffith was an American film director who created a lot of what we consider “the structure” of feature films. His 1915 epic The Birth of a Nation brought the technique of cinematic storytelling into the future, while consequently keeping its subject matter in the objectionable past.

For more on Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation (and its complicated legacy), check out this poignant interview clip with Spike Lee .

History of Filmmaking • Spike Lee on ‘The Birth of a Nation’

As Lee suggests, it’s important to acknowledge the technical achievement of films like The Birth of a Nation and Gone With the Wind without condoning their horrid subject matter.

As another great director once said: “tomorrow’s democracy discriminates against discrimination. Its charter won’t include the freedom to end freedom.” – Orson Welles.

Griffith made more than a few Hollywood epics in his time, but none were more famous than The Birth of a Nation .

Okay, now that we reviewed the foundations of the Hollywood epic, let’s move on to pre-code Hollywood.

PRE-CODE HOLLYWOOD

A History of Film • James Cagney in ‘The Public Enemy’

- Pre-Code Hollywood – a period in Hollywood history after the advent of sound but before the institution of the Hays Code – circa ~1927-1934.

- Major Pre-Code stars: Ruth Chatterton, Warren William, James Cagney.

- Major Pre-Code films: Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1931), The Public Enemy (1931), Baby Face (1933).

Pre-Code Hollywood was wild. Not just wild in an uninhibited sense, but in a thematic sense too. Films produced during the pre-Code era often focused on illicit subject matter, like bootlegging, prostitution, and murder – that wasn't the status quo for Hollywood – and it wouldn’t be again until 1968.

We’ll get to why that year is important for film history in a bit, but first let’s review pre-Code Hollywood with a couple of selected scenes from Kevin Wentink on YouTube.

Movie Film History • Pre-Code Classic Clips

Pre-Code movies were jubilant in their creativity; largely because they were uncensored . But alas, their period was short-lived. In 1934, MPPDA Chairman William Hays instituted the Motion Picture Production Code banning explicit depictions of sex, violence, and other “sinful” deeds in movies.

Learn more about Pre-Code Hollywood →

Development of Movies

The early golden age and color in film.

The 1930s and early 1940s produced some of the greatest movies of all-time – but they also changed everything about the movie-making process. By the end of the Pre-Code era, the free independent spirit of filmmaking had all but evaporated; Hollywood studios had vertically integrated their business operations, which meant they conceptualized, produced, and distributed everything “in-house.”

That doesn’t mean movies made during these years were bad though. Quite the contrary – perhaps the two greatest American films ever made, Citizen Kane and Casablanca , were made between 1934 and 1944.

But despite their enormous influence, neither Citizen Kane nor Casablanca could hold a candle to the influence of another film from this decade: The Wizard of Oz .

The Wizard of Oz wasn’t the first film to use Technicolor , but it was credited with bringing color to the masses. For more on the industry-altering introduction of color, check out this video on The Wizard of Oz from Vox.

When Was Color Movies Invented? • How Technicolor Changed Movies

Technicolor was groundbreaking for cinema, but the dye-transfer process of its colorization was hard… and cost prohibitive for studios. So, camera manufacturers experimented with new processes to streamline color photography. Overtime, they were rewarded with new technologies and techniques.

Learn more about Technicolor →

Cinema Eras

Wartime and propaganda films.

In 1937, Benito Mussolini founded Cinecittà , a massive studio that operated under the slogan “Il cinema è l'arma più forte,” which translates to “the cinema is the strongest weapon.” During this time, countries all around the world used cinema as a weapon to influence the minds and hearts of their citizens.

This was especially true in the United States – prolific directors like Frank Capra, John Ford, John Huston, George Stevens, and William Wyler enlisted in the U.S. Armed Forces to make movies to support the U.S. war cause.

Documentarian Laurent Bouzereau made a three-part series about the war films of Capra, Ford, Huston, Stevens, and Wyler. Check out the trailer for Five Came Back below.

A History of Film • Five Came Back Trailer

Wartime film is important to explore because it teaches us about how people interpret propaganda. For posterity’s sake, let’s define propaganda as biased information that’s used to promote political points.

Propaganda films are often regarded with a negative connotation because they sh0w a one-sided perspective. Films of this era – such as those commissioned for the US Department of War’s Why We Fight series – were one-sided because they were made to counter the enemy’s rhetoric. It’s important to note that “one-sided” doesn’t mean “wrong” – in the case of the Why We Fight series, I think most people would agree that the one-sidedness was appropriate.

Over time, wartime film became more nuanced – a point proven by the 1966 masterwork The Battle of Algiers .

History of Movies

Post-war film movements.

Global cinema underwent a renaissance after World War II; technically, creatively, and conceptually. We’re going to cover a few of the most prominent post-war film movements, starting with Italian Neorealism.

ITALIAN NEOREALISM

Movie Film History • Still from Vittorio De Sica’s ‘Umberto D.’

- Italian Neorealism (1944-1960) – an Italian film movement that brought filmmaking to the streets; defined by depictions of the Italian state after World War II.

- Major Italian Neorealist film-makers: Vittorio De Sica, Roberto Rossellini, Michelangelo Antonioni, Luchino Visconti, Federico Fellini .

- Major Italian Neorealist films: Rome, Open City (1945), Bicycle Thieves (1948), La Strada (1954), Il Posto (1961).

Martin Scorcese called Italian Neorealism “the rehabilitation of an entire culture and people through cinema.” World War II devastated the Italian state: socially, economically, and culturally.

It took people’s lives and jobs, but perhaps more importantly, it took their humanity. After the War, the people needed an outlet of expression, and a place to reconstruct a new national identity. Here’s a quick video on Italian Neorealism.

Movie History • How Italian Neorealism Brought the Grit of the Streets to the Big Screen by No Film School

Italian Neorealism produced some of the greatest films ever made. There’s some debate as to when the movement started and ended – some say 1943-1954, others say 1945-1955 – but I say it started with Rome, Open City and ended with Il Posto . Why? Because those movies perfectly encompass the defining arc of Italian Neorealism, from street-life after World War II to the rise of bureaucracy. Rome, Open City shows Italy in the thick of chaos, and Il Posto shows Italy on the precipice of a new era.

The legacy of Italian Neorealism lives on in the independent filmmaking of directors like Richard Linklater, Steven Soderbergh, and Sean Baker.

Learn more about Italian Neorealism →

FRENCH NEW WAVE

Development of Movies • Still From Jean-Luc Godard’s Breathless

- French New Wave (1950s onwards) – or La Nouvelle Rogue, a French art movement popularized by critics, defined by experimental ideas – inspired by old-Hollywood and progressive editing techniques from Orson Welles and Alfred Hitchcock.

- Major French New Wave filmmakers: Jean-Luc Godard , François Truffaut , Agnes Varda.

- Major French New Wave films: The 400 Blows (1959), Breathless (1960), Cleo from 5 to 7 (1962).

The French New Wave proliferated the auteur theory , which suggests the director is the author of a movie; which makes sense considering a lot of the best French New Wave films featured minimalist narratives. Take Jean-Luc Godard’s Breathless for example: the story is secondary to audio and visuals. The French New Wave was about independent filmmaking – taking a camera into the streets and making a movie by any means necessary.

Here’s a quick video on The French New Wave by The Cinema Cartography.

History of Filmmaking • Breaking the Rules With the French New Wave by The Cinema Cartography

It’s important to note that the pioneers of the French New Wave weren’t amateurs – most (but not all) were critics at Cahiers du cinéma , a respected French film magazine. Writers like Godard, Rivette, and Chabrol knew what they were doing long before they released their great works.

Other directors, like Agnes Varda and Alain Resnais, were members of the Left Bank, a somewhat more traditionalist art group. Left Bank directors tended to put more emphasis on their narratives as opposed to their Cahiers du cinéma counterparts.

The French New popularized (but did not invent) innovative filmmaking techniques like jump cuts and tracking shots . The influence of the French New Wave can be seen in music videos, existentialist cinema, and French film noir .

Learn more about the French New Wave →

Learn more about the Best French New Wave Films →

SCANDINAVIAN REVIVAL

A History of Film • Still from Ingmar Bergman’s ‘The Seventh Seal’

- Scandinavian Revival (1940s-1950s) – a filmmaking movement in Scandinavia, particularly Denmark and Sweden, defined by monochrome visuals, philosophical quandaries, and reinterpretations of religious ideals.

- Major Scandinavian Revival filmmakers: Carl Theodor Dreyer and Ingmar Bergman.

- Major Scandinavian Revival films: Day of Wrath (1943), The Seventh Seal (1957), Wild Strawberries (1957).

Swedish, Danish, and Finnish films have played an important role in cinema for more than 100 years. The Scandinavian Revival – or renaissance of Scandinavian-centric films from the 1940s-1950s – put the films of Sweden, Denmark, and Finland in front of the world stage.

Here’s a quick video on the works of the most famous Scandinavian director of all-time: Ingmar Bergman .

History of Cinema • Ingmar Bergman’s Cinema by The Criterion Collection

The influence of Scandinavian Revival can be seen in the works of Danish directors like Thomas Vinterberg and Lars von Trier , as well as countless other filmmakers around the world.

BENGALI CINEMA

History of Motion Pictures • Still from Satyajit Ray’s ‘Pather Panchali’

- Bengali Cinema – or the cinema of West Bengal; also known as Tollywood, helped develop arthouse films parallel to the mainstream Indian cinema.

- Major Bengali filmmakers: Satyajit Ray and Mrinal Sen.

- Major Bengali films: Pather Panchali (1955) and Bhuvan Shome (1969).

The Indian film industry is the biggest film industry in the world. Each year, India produces more than a thousand feature-films. When most people think of Indian cinema, they think of Bollywood “song and dance” masalas – but did you know the country underwent a New Wave (similar to France, Italy, and Scandinavia) after World War II? The influence of the Indian New Wave, or classic Bengali cinema, is hard to quantify; perhaps it’s better expressed by the efforts of the Academy Film Archive, Criterion Collection, and L'Immagine Ritrovata film restoration artists. Here's an introduction to one of India's greatest directors, Satyajit Ray.

Evolution of Cinema • How Satyajit Ray Directs a Movie

In 2020, Martin Scorsese said, “In the relatively short history of cinema, Satyajit Ray is one of the names that we all need to know, whose films we all need to see.” Ray is undoubtedly one of the preeminent masters of international cinema – and his name belongs in the conversation with Hitchcock, Renoir, Kurosawa, Welles, and all the other trailblazing filmmakers of the mid-20th century.

Learn more about Indian Cinema →

OTHER POST-WAR & NEW WAVE MOVEMENTS

How Has Film Changed Over Time? • Still from Akira Kurosawa’s ‘Stray Dog’

Italy, France, Denmark, Sweden, Finland, and India weren’t the only countries that underwent “New Waves” after World War II; Japan, Iran, Great Britain, and Russia had minor film revolutions as well.

In Japan, directors like Akira Kurosawa and Yasujirō Ozu introduced new filmmaking techniques to the masses; their 1940s-1950s films were great, but some filmmakers, like Hiroshi Teshigahara and Nagisa Ōshima felt they were better suited to make films about “modern” Japan.

Here’s a quick video on the Japanese New Wave from Film Studies for YouTube.

Cinema Eras • Japanese New Wave Video Essay by Film Studies for YouTube

Some cinema historians combine the Japanese New Wave with the post-war era. For simplicity’s sake, we’ll do the same: the major films of this era (1940s-1960s) include Rashomon (1950), Tokyo Story (1953), and Seven Samurai (1954).

The Iranian New Wave began about fifteen years after the end of World War II, circa 1960-onwards. Iranian cinema is an important part of Iranian culture. Here’s a quick video on Iranian cinema from BBC News.

Important Dates in Film History • Spotlight on Iran’s Film Industry via BBC News

Cinema historians widely consider Dariush Mehrjui’s The Cow (1969) to be a foundational film for the movement. Abbas Kiarostami is perhaps the most famous Iranian filmmaker of all-time. His film Close-Up (1990) is regarded as one of the greatest films ever produced in Iran.

The British New Wave was a minor film movement that was defined by kitchen-sink realism – or depictions of ordinary life. Many filmmakers of the British New Wave were critics before they were directors; and they wanted to depict the average life of Britain through a filmic eye.

Here’s a lecture on the British New Wave from Professor Ian Christie at Gresham College.

History of Filmmaking • Street-Life and New Wave British Cinema by Gresham College

The British New Wave became synonymous with Cinéma vérité (cinema of truth) over the course of its brief existence. Some of the major pictures of the movement include: Look Back in Anger (1959) and Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (1960).

Russian cinema is complex… probably just as complex as American cinema. We could spend 100 pages talking about Russian cinema – but that’s not the focus of this article. We already talked about Soviet Montage Theory, so let’s skip ahead to post World War II Soviet cinema.

When I think of post-war Soviet cinema, I think of one name: Andrei Tarkovsky . Tarkovsky directed internationally-renowned films like Andrei Rublev (1969), Solaris (1972), and Stalker (1979) in his brief career as the Soviet Union’s pre-eminent maestro.

Here’s a deep dive into the works of Tarkovsky by “Like Stories of Old.”

Film Industry Timeline • Praying Through Cinema – Understanding Andrei Tarkovsky by Like Stories of Old

Tarkovsky wasn’t the only great filmmaker in the post-war Soviet Union – but he was probably the best. I’d be remiss if I didn’t use this section to focus on him.

History of Film Timeline

The golden age of hollywood.

The Hollywood Golden Age began with the fall of pre-Code Hollywood (1934) and lasted until the birth of New Hollywood (1968).

- Major stars of the Hollywood Golden Age: Humphrey Bogart, Cary Grant, Katharine Hepburn, Audrey Hepburn, Elizabeth Taylor, Clark Gable, Ingrid Bergman, Henry Fonda, Kirk Douglas, Gregory Peck, Lauren Bacall, Grace Kelly, James Dean, Marlon Brando.

- Major filmmakers of the Hollywood Golden Age: Cecil B. DeMille , Orson Welles , Billy Wilder , Frank Capra , John Huston , Alfred Hitchcock , John Ford , Elia Kazan , David Lean , Joseph Manckiewicz.

Notice how many names we included? It’s ridiculous – it would be wrong to omit any of them; and still, there are probably dozens of iconic figures missing. The Hollywood Golden Age was all about stars. Stars sold pictures and the studios knew it. “Hepburn” could sell a movie every time; it didn’t matter which Hepburn – or what the movie was about.

Here’s a breakdown of the Hollywood Golden Age from Crash Course.

History of Movies • The Golden Age of Hollywood by Crash Course

There are a few sub-eras within the Hollywood Golden Age era; let’s break them down in detail.

Important Dates in Film History • Photo of MPPDA Chairman William Hays

In 1934, Chairman William Hays of the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America instituted a production code that banned graphic cinematic depictions of sex, violence, and other illicit deeds.

The “Production Code” or “ Hays Code ” was responsible for the censorship of Hollywood films for 34 years.

For more on the history of Hollywood censorship and movie ratings, check out the video from Filmmaker IQ below.

How Has Film Changed Over Time? • History of Hollywood Censorship by Filmmaker IQ

The Hays Code kept cinema tame, which led to Hollywood romanticism. But it also made cinema unrealistic, which made the American public yearn for improbable outcomes. Not to mention that it set race relations back an indeterminable amount of years. The Hays Code specifically forbade miscegenation, or “the breeding of people of different races.”

Ultimately, the censorship of Hollywood films was about keeping power in the hands of people with power. It had some positive unintended outcomes – but it wasn’t worth the cost of suppression.

Learn more about the Hays Code →

Learn more about the history of movie censorship →

Film Industry Timeline • Still from Nicholas Ray’s ‘In a Lonely Place’

Film noir is a style of film that’s defined by moralistic themes, high contrast lighting, and mysterious plots. Oftentimes, film noirs feature hardboiled protagonists . It’s important to note that film noir is a style, not a film movement. As such, we won’t list “film noir directors,” but we will list some iconic examples of film noir.

Major Hollywood film noirs: The Maltese Falcon (1941), Double Indemnity (1944), Sunset Boulevard (1950).

Hollywood film noirs were inspired by classic detective fiction stories, like those of Arthur Conan Doyle and Edgar Allan Poe. Over time, film noir was adopted as a style around the world – most famously in Great Britain with Carol Reed’s The Third Man .

Here’s a video on defining film noir from Jack’s Movie Reviews.

Eras of Movies • Defining Film Noir by Jack’s Movie Reviews

We could spend another 50 pages on film noir (like many other topics in this compendium) – but instead, let’s continue on.

Learn more about film noir →

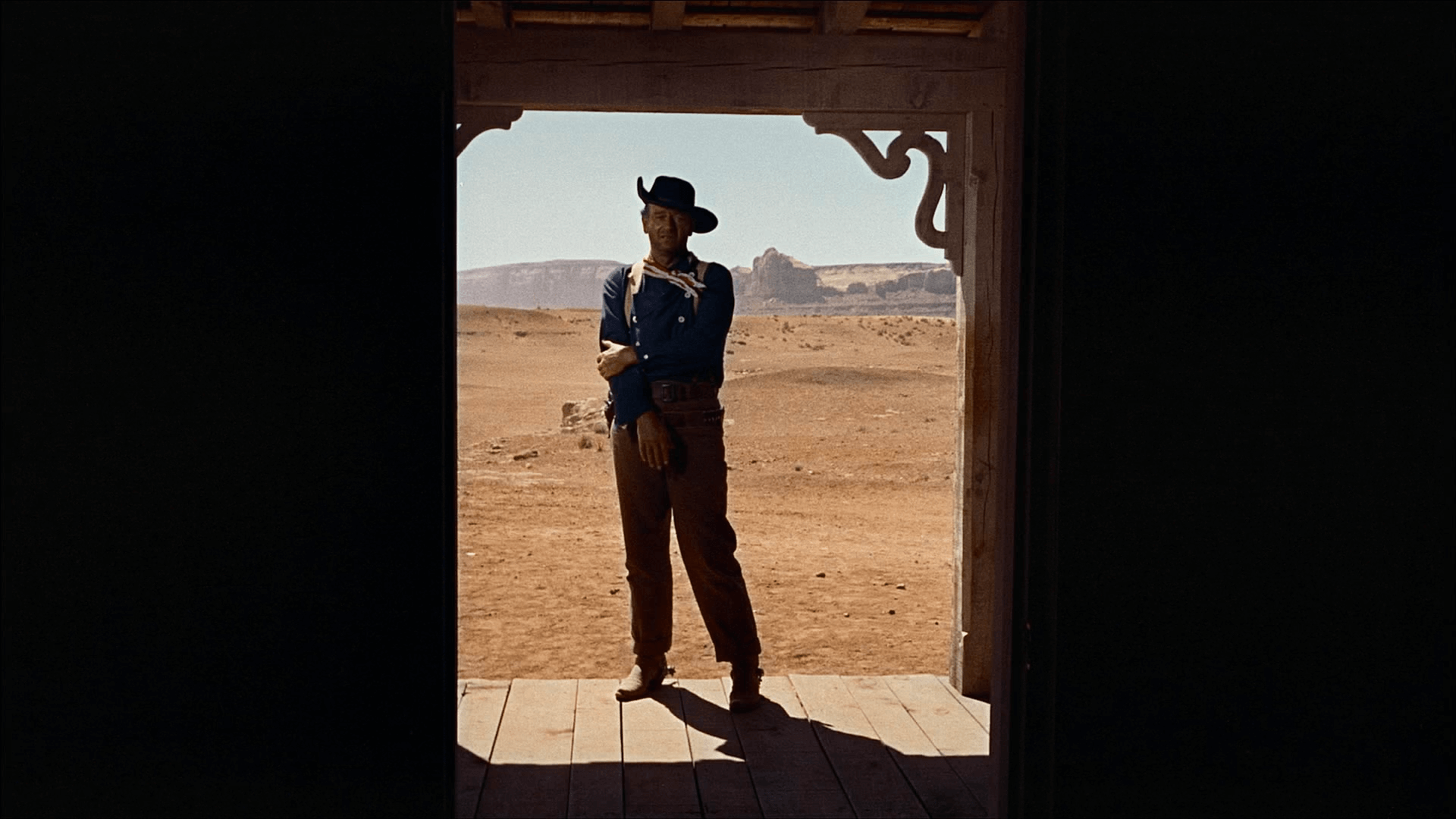

How Movies Have Changed Over Time • Still from John Ford’s ‘The Searchers’

Hollywood westerns were incredibly popular during the Golden Age. Why? Because the American people loved stories of lawlessness and expansion, dating all the way back to Erastus Beadle’s dime novels – making the western the perfect subgenre for vicarious cinema.

Major Hollywood westerns: Stagecoach (1939), High Noon (1952), The Searchers (1956).

Westerns, much like film noirs, allowed repressed audiences to feel alive at the movie theater. Remember: Hollywood films were censored during the Golden Age, which meant you couldn’t find graphic violence or pornography at the theaters. So, audiences took what they could get – which was usually film noirs and Westerns.

Here’s a video on the history of Westerns in Hollywood cinema.

Evolution of Film • Western Movies History by Ministry of Cinema

Hollywood westerns inspired a global fascination with cowboys, mercenaries, and gunslingers, directly leading to samurai cinema, spaghetti westerns, zapata westerns, and neo-westerns.

Learn more about Spaghetti Westerns →

Learn more about Neo-Westerns →

McCARTHYISM & THE BLACKLIST

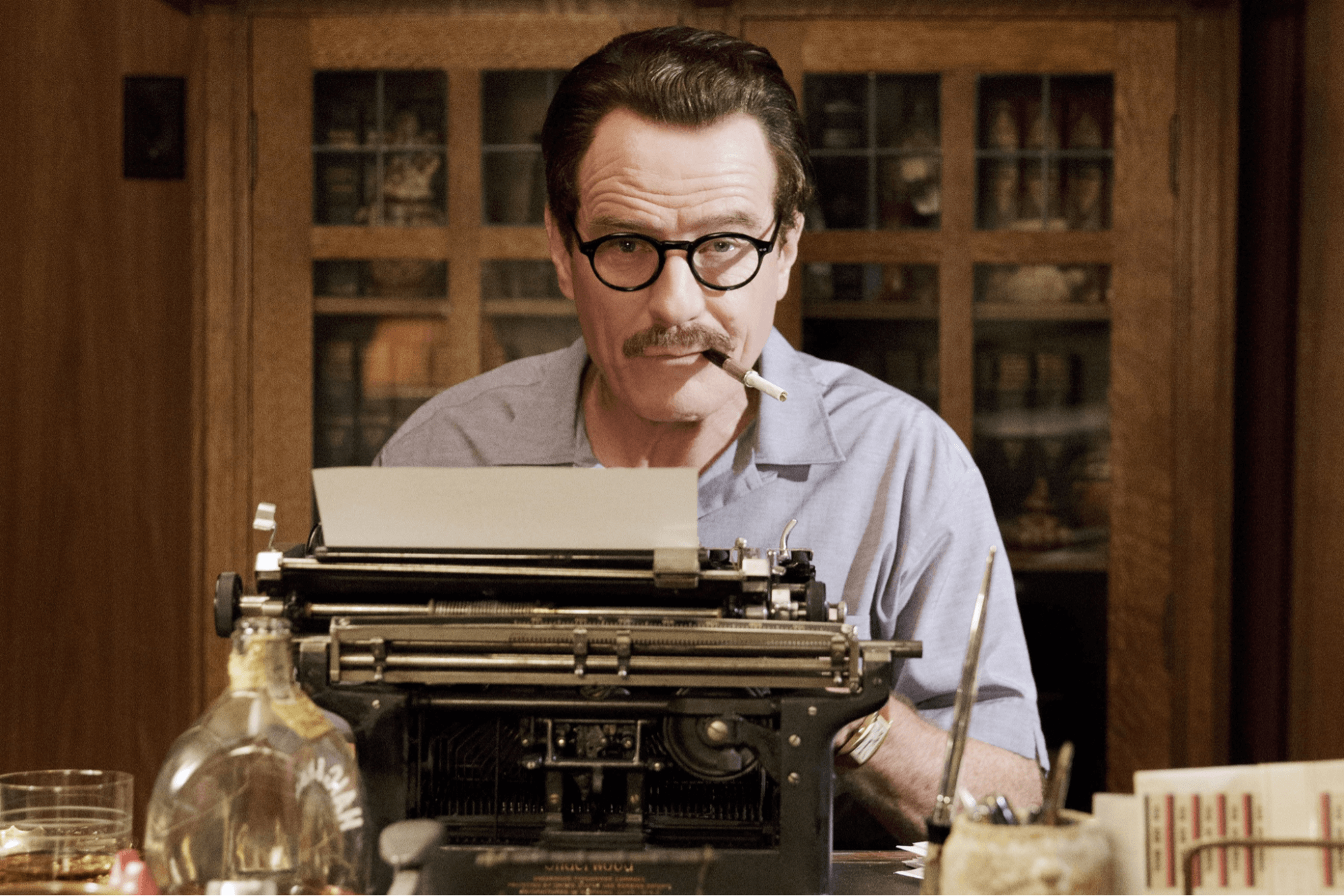

How Movies Have Changed Over Time • Bryan Cranston as Blacklisted Screenwriter Dalton Trumbo

In 1947, the state of Wisconsin elected notorious fear-monger Joseph McCarthy as senator of their state. McCarthy hated free-speech – that’s not a one-sided perspective, that’s the truth. McCarthy spent his entire career demagoguing, and his legacy shows that.

In 1950, ten Hollywood screenwriters were summoned to appear before the United States Congress House of Un-American Activities, largely because of McCarthy's divisive rhetoric against communist sympathizers. The screenwriters were cited for contempt of congress and fired from their jobs, and thus, the blacklist was born.

For more on McCarthyism and the Hollywood blacklist , check out the video from Ted-Ed below.

The History of Film • McCarthyism and the Blacklist by Ted-Ed

The Hollywood blacklist derailed the careers of hundreds of writers, directors, and producers from 1950-1960. The blacklist ended when Kirk Douglas credited Dalton Trumbo – one of the most famous blacklisted screenwriters – as the screenwriter of Stanley Kubrick’s Spartacus , effectively taking back control of Hollywood.

Learn more about the Hollywood Blacklist →

THE PARAMOUNT CASE

The History of Film • Paramount Studios Classic Style Logo

In 1948, the Supreme Court of the United States ruled that the five major motion picture studios: Paramount, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM), Warner Bros., 20th Century Fox, and RKO violated the U.S. Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890.

As a result of the decision, movie studios could no longer solely create and distribute movies to their own theaters.

It may not sound important, but the Paramount Case changed everything for American cinema. Here’s a quick video on the Case and its lasting impact on Hollywood.

The History of Filmmaking • Film History 101: The Paramount Decree by Omar Rivera

The Paramount Case opened the door for international films and independent theaters. It also gave businesses more freedom to show movies outside of the MPPDA ratings system.

Evolution of Cinema

New hollywood.

Movie History • Still from Arthur Penn’s’ Bonnie and Clyde’

- New Hollywood, otherwise known as the Hollywood New Wave, introduced “the film school generation” to Hollywood. New Hollywood films are defined as larger in scope, darker in subject matter, and overtly more graphic than their Golden Age predecessors.

- Major New Hollywood filmmakers: George Lucas , Steven Spielberg , Martin Scorsese , Brian De Palma , Peter Bogdanovich, Woody Allen , Francis Ford Coppola , James Cameron .

- Major New Hollywood films: Bonnie and Clyde (1967), The Graduate (1967), Easy Rider (1969), Midnight Cowboy (1969), The Godfather (1972), American Graffiti (1973).

New Hollywood ushered American filmmaking into a new era by returning to the popular genres of the pre-Code era, such as gangster films and sex-centric films. It also marked the emergence of “film-school” directors like George Lucas, Steven Spielberg, and Martin Scorsese. It’s clear from watching New Hollywood films that the writers and directors who produced them were acutely aware of cinema history.

During this era, writers like Woody Allen employed themes of existentialist cinema found in the French New Wave and Italian Neorealism (among other movements). Directors like Martin Scorsese utilized advanced framing techniques pioneered by masters of the pre-war era.

For more on New Hollywood, check out this feature documentary based Peter Biskind's seminal book "Easy Riders, Raging Bulls."

Movie History • How New Hollywood Was Born

New Hollywood (and its immediate aftermath) produced some of the greatest films of all-time: such as The Godfather (1972), The Godfather Part II (1974), Chinatown (1974), Taxi Driver (1976), Network (1976), and Annie Hall (1977).

Somewhat tragically, New Hollywood ended with the emergence of blockbuster films – such as Jaws (1975) and Star Wars (1977) – in the mid to late 1970s.

Learn more about New Hollywood →

Eras of Movies

Dogme 95 and independent movements.

Big-budget movies dominated the movie-scene after New Hollywood ended. Suddenly, cinema became more of a spectacle than an art-form. That’s not to say movies produced during this era (1975-1995) were bad – some big-budget films, like Back to the Future (1985) and Jurassic Park (1993) were financially successful and critically acclaimed; and writer/directors like John Hughes found enormous success making studio films about seemingly mundane life.

But despite the financial prospect of making contrived studio films, some filmmakers decided to go back to their roots and make films independently, much in the vein of the artists of the French New Wave. This spirit inspired the Danish Dogme 95 movement and the American Independent movement.

Evolution of Film • Photo Still from ‘Festen’ by Thomas Vinterberg

D0gme 95 – a Danish film movement that brought filmmaking back to its primal roots: no non-diegetic sound, no superficial action, and no director credit.

Major Dogme 95 filmmakers: Thomas Vinterberg and Lars von Trier

Major Dogme 95 films: Dogme #1 – Festen (1998), Dogme #2 – The Idiots (1998), Dogme #12 – Italian for Beginners (2000).

It’s ironic that Dogme 95 , which states the director must not be credited, is perhaps best known for the fame of two of its founders: Thomas Vinterberg and Lars von Trier. Dogme 95 sought to rid cinema of extravagant special effects and challenging productions by making the filmmaking process as simple as possible. To do this, its founders created the Vows of Chastity: a ten-part manifesto for Dogme 95 filmmaking.

Check out a video on the Vows of Chastity and Dogme 95 below.

History of Cinema • Vows of Chastity – Films of Dogme 95 by FilmStruck

Ultimately, the Vows of Chastity proved too limiting for filmmakers – but their influence lives on in New Danish cinema and independent films all over the world.

Learn more about Dogme 95 →

History of Cinema • Still from Kevin Smith’s ‘Clerks’

Indie film – or late 80s, early 90s cinema produced outside of the major motion picture system – was about experimenting with new cinematic forms, pushing the Generation Next agenda, and making art by any means necessary.

Major indie filmmakers: Richard Linklater , Wes Anderson , Steven Soderbergh , Jim Jarmusch .

Major indie films: Sex, Lies, and Videotape (1989), Slacker (1990), and Bottle Rocket (1994).

The American indie movement launched the careers of a myriad of great directors. It also marked the beginning of a major decline for film. The advent of digital cameras and DVDs meant film was becoming a luxury. Conversely, it meant procuring the necessary equipment needed to make movies was easier than ever.

Indie-films introduced the idea that anybody could make movies. For better or worse, the point proved to be true. The '90s and early 2000s were littered with independently produced, scarcely funded movies. It was unrestrained, but it was also liberating.

Check out this video on no-budget filmmaking from The Royal Ocean Film Society to learn more about the indie movement.

Evolution of Cinema • Lessons for the No-Budget Feature by The Royal Ocean Film Society

The indie movement (as it was known then) ended when the major studios (like Disney and Turner) bought the independent studios (like Miramax and New Line). Today, we often refer to minimalist, low-budget movies as independent, but the truth is just about every production studio is owned by a conglomerate.

How Has the Film Industry Changed?

New distribution methods.

The current state of cinema is in flux due to a wide array of issues, including (but not limited to) the economic impact of the Covid-19 pandemic, the wide-adoption of new streaming services from first-party producers, i.e. Netflix, Disney, Paramount, etc., and the growth of new media forms.

Over the last few years, big-budget epics like Marvel’s The Avengers and Star Wars have performed well at the U.S. and Chinese box-office, but their success has often come at the expense of medium-budget movies; the result being a deeper lining of the pockets of exorbitantly wealthy corporations.

Still, there’s a lot of money to be made – a point perhaps best proven by the rise of the Chinese film industry. In 2020, China overtook North America as the world’s biggest box-office market, per THR. Check out a video on Hengdian, China’s largest film studio from South China Morning Report.

Movie History • Inside China’s Largest Film Studio by South China Morning Report

Movies seem to get bigger and bigger every year but the development of computer-generated-imagery and compositing techniques has given filmmakers the technology to create vast worlds in limited spaces.

So: what’s next for film? Who’s to say for certain? The future of the industry looks cloudy – but there’s definite promise on the horizon. More people have cinema-capable cameras in their pocket today than ever before. Perhaps the next great movement will take off soon.

Related Posts

- What is CinemaScope →

- When Was the Camera Invented →

- What Was the First Movie Ever Made →

100 Years of Cinematography

The history of film includes a lot more than what we went over here. In 2019, the American Society of Cinematographers celebrated 100 years of great cinematography with a list of legendary works. In our next article, we break down some of the ASC’s choices with video examples. Follow along as we look at the work of Conrad Hall, Vittorio Storaro, and more.

Up Next: Best Cinematography of All-Time →

Showcase your vision with elegant shot lists and storyboards..

Create robust and customizable shot lists. Upload images to make storyboards and slideshows.

Learn More ➜

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- Pricing & Plans

- Product Updates

- Featured On

- StudioBinder Partners

- Ultimate Guide to Call Sheets

- How to Break Down a Script (with FREE Script Breakdown Sheet)

- The Only Shot List Template You Need — with Free Download

- Managing Your Film Budget Cashflow & PO Log (Free Template)

- A Better Film Crew List Template Booking Sheet

- Best Storyboard Softwares (with free Storyboard Templates)

- Movie Magic Scheduling

- Gorilla Software

- Storyboard That

A visual medium requires visual methods. Master the art of visual storytelling with our FREE video series on directing and filmmaking techniques.

We’re in a golden age of TV writing and development. More and more people are flocking to the small screen to find daily entertainment. So how can you break put from the pack and get your idea onto the small screen? We’re here to help.

- Making It: From Pre-Production to Screen

- What is Method Acting — 3 Different Types Explained

- How to Make a Mood Board — A Step-by-Step Guide

- What is a Mood Board — Definition, Examples & How They Work

- How to Make a Better Shooting Schedule with a Stripboard

- Ultimate Guide to Sound Recording: Audio Gear and Techniques

- 1 Pinterest

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

1 A Brief History of Cinema

Leland Stanford was bored.

In 1872, Stanford was a wealthy robber baron, former Governor of California, and horse racing enthusiast with way too much time on his hands. Spending much of that time at the track, he became convinced that a horse at full gallop lifted all four hooves off the ground. His friends scoffed at the idea. Unfortunately, a horse’s legs moved so fast that it was impossible to tell with the human eye. So he did what really wealthy people do when they want to settle a bet, he turned to a nature photographer, Eadweard Muybridge, and offered him $25,000 to photograph a horse mid gallop.

Six years later, after narrowly avoiding a murder conviction (but that’s another story), Muybridge perfected a technique of photographing a horse in motion with a series of 12 cameras triggered in sequence. One of the photos clearly showed that all four of the horse’s hooves left the ground at full gallop. Stanford won the bet and went on to found Stanford University. Muybridge pocketed the $25,000 and became famous for the invention of series photography , a critical first step toward motion pictures.

Of course, the mechanical reproduction of an image had already been around for some time. The Camera Obscura , a technique for reproducing images by projecting a scene through a tiny hole that is inverted and reversed on the opposite wall or surface (think pinhole camera), had been around since at least the 5th century BCE, if not thousands of years earlier. But it wasn’t until a couple of French inventors, Nicephore Niepce and Louis Daguerre, managed to capture an image through a chemical process known as photoetching in the 1820s that photography was born. By 1837, Niepce was dead (best not to ask too many questions about that) and Daguerre had perfected the technique of fixing an image on a photographic plate through a chemical reaction of silver, iodine and mercury. He called it a daguerreotype . After himself. Naturally.

But to create the illusion of movement from these still images would require further innovation. The basic concept of animation was already in the air through earlier inventions like the magic lantern and eventually the zoetrope . But a photo-realistic recreation of movement was unheard of. That’s where Muybridge comes in. His technique of capturing a series of still images in quick succession laid the groundwork for other inventors like Thomas Edison, Woodville Latham and Auguste and Louis Lumiere to develop new ways of photographing and projecting movement. Crucial to this process was the development of strips of light-sensitive celluloid film to replace the bulky glass plates used by Muybridge. This enabled a single camera to record a series of high-speed exposures (rather than multiple cameras taking a single photo in sequence). It also enabled that same strip of film to be projected at an equally high speed, creating the illusion of movement through a combination of optical and neurological phenomena. But more on that in the next chapter.

By 1893, 15 years after Muybridge won Stanford’s bet, Edison had built the first “movie studio,” a small, cramped, wood-frame hut covered in black tar paper with a hole in the roof to let in sunlight. His employees nicknamed it the Black Maria because it reminded them of the police prisoner transport wagons in use at the time (also known as “paddy wagons” with apologies to the Irish). One of the first films they produced was a 5 second “scene” of a man sneezing.

Riveting stuff. But still, movies were born.

There was just one problem: the only way to view Edison’s films was through a kinetoscope , a machine that allowed a single viewer to peer into a viewfinder and crank through the images. The ability to project the images to a paying audience would take another couple of years.

In 1895, Woodville Latham, a chemist and Confederate veteran of the Civil War, lured away a couple of Edison’s employees and perfected the technique of motion picture projection. In that same year, over in France, Auguste and Louis Lumiere invented the cinematographe which could perform the same modern miracle. The Lumiere brothers would receive the lion’s share of the credit, but Latham and the Lumieres essentially tied for first place in the invention of cinema as we know it.

It turns out there was another French inventor, Louis Le Prince (apparently we owe a lot to the French), who was experimenting with motion pictures and had apparently perfected the technique by 1890. But as he was preparing for a public demonstration in the U.S. that same year – potentially eclipsing Edison’s claim on the technology – he mysteriously vanished from a train between Dijon and Paris. His body and luggage, including his invention, were never found. Conspiracy theories about his untimely disappearance have circulated ever since (we’re looking at you, Thomas Edison).

Those early years of cinema were marked by great leaps forward in technology, but not so much forward movement in terms of art. Whether it was Edison’s 5-second film of a sneeze, or the Lumieres’ 46-second film Workers Leaving a Factory (which is exactly what it sounds like), the films were wildly popular because no one had seen anything like them, not because they were breaking new ground narratively.

There were, of course, notable exceptions. Alice Guy-Blaché was working as a secretary at a photography company when she saw the Lumieres’ invention in 1895. The following year she wrote, directed and edited what many consider the first fully fictional film in cinema history, The Cabbage Fairy (1896):

But it was George Melies who became the most well-known filmmaker-as-entertainer in those first few years. Melies was a showman in Paris with a flare for the dramatic. He was one of the first to see the Lumieres’ cinematographe in action in 1895 and immediately saw its potential as a form of mass entertainment. Over the next couple of decades he produced hundreds of films that combined fanciful stage craft, optical illusions, and wild storylines that anticipated much of what was to come in the next century of cinema. His most famous film, A Trip to the Moon , produced in 1902, transported audiences to the surface of the moon on a rocket ship and sometimes even included hand-tinted images to approximate color cinematography.

He was very much ahead of his time and would eventually be immortalized in Martin Scorsese’s 2011 film Hugo .

By the start of the 20th century, cinema had become a global phenomenon. Fortunately, many of those early filmmakers had caught up with Melies in terms of the art of cinema and its potential as an entertainment medium. In Germany, filmmakers like Fritz Lange and Robert Weine helped form one of the earliest examples of a unique and unified cinematic style, consisting of highly stylized, surreal production designs and modernist, even futuristic narrative conventions that came to be known as German Expressionism . Weine’s The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920) was a macabre nightmare of a film about a murderous hypnotist and is considered the world’s first horror movie.

And Lange’s Metropolis (1927) was an epic science-fiction dystopian fantasy with an original running time of more than 2 hours.

Meanwhile in Soviet Russia, Lev Kuleshov and Sergei Eisenstein were experimenting with how the creative juxtaposition of images could influence how an audience thinks and feels about what they see on screen (also known as editing , a relatively new concept at the time). Through a series of experiments, Kuleshov demonstrated that it was this juxtaposition of images, not the discrete images themselves, that generated meaning, a phenomenon that came to be known as The Kuleshov Effect . Eisenstein, his friend and colleague, applied Kuleshov’s theories to his own cinematic creations, including the concept of montage : a collage of moving images designed to create an emotional effect rather than a logical narrative sequence. Eisenstein’s most famous use of this technique is in the Odessa steps sequence of his historical epic, Battleship Potemkin (1925).

But it was the United States that was destined to become the center of the cinematic universe, especially as it grew into a global mass entertainment medium. Lois Weber was an early innovator and the first American director, male or female, to make a narrative feature film, The Merchant of Venice (1914). Throughout her career, Weber would pursue subjects considered controversial at the time, such as abortion, birth control and capital punishment (it helped that she owned her own studio). But it wasn’t just her subject matter that pushed the envelope. For example, in her short film, Suspense (1913) she pioneered the use of intercutting and basically invented split screen editing.

Others, like D. W. Griffith, followed suit (though it’s doubtful Griffith would have given Weber any credit). Like Weber, Griffith helped pioneer the full-length feature film and invented many of the narrative conventions, camera moves and editing techniques still in use today. Unfortunately, many of those innovations were first introduced in his ignoble, wildly racist (and wildly popular at the time) Birth of a Nation (1915). Griffith followed that up the next year with the somewhat ironically-titled Intolerance (1916), a box office disappointment but notable for its larger than life sets, extravagant costumes, and complex story-line that made George Melies’s creations seem quaint by comparison.

Weber, Griffith and many other filmmakers and entrepreneurs would go on to establish film studios able to churn out hundreds of short and long-form content for the movie theaters popping up on almost every street corner.

CINEMA GOES HOLLYWOOD

This burgeoning new entertainment industry was not, however, located in southern California. Not yet, anyway. Almost all of the production facilities in business at the time were in New York, New Jersey or somewhere on the Eastern seaboard. Partly because the one man who still controlled the technology that made cinema possible was based there: Thomas Edison. Edison owned the patent for capturing and projecting motion pictures, essentially cornering the market on the new technology (R.I.P. Louis Le Prince). If you wanted to make a movie in the 1900s or 1910s, you had to pay Edison for the privilege.

Not surprisingly, a lot of would-be filmmakers bristled at Edison’s control over the industry. And since patent law was difficult to enforce across state lines at the time, many of them saw California as an ideal place to start a career in filmmaking. Sure, the weather was nice. But it was also as far away from the northeast as you could possibly get within the continental United States, and a lot harder for Edison to sue for patent violations.

By 1912, Los Angeles had replaced New York as the center of the film business, attracting filmmakers and entertainment entrepreneurs from around the world. World-renowned filmmakers like Ernst Lubitsch from Germany, Erich von Stroheim from Austria, and an impish comedian from England named Charlie Chaplin, all flocked to the massive new production facilities that sprang up around the city. Universal Pictures, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM), Warner Bros., all of them motion picture factories able to mass-produce dozens, sometimes hundreds of films per year. And they were surrounded by hundreds of other, smaller companies, all of them competing for screen space in thousands of new movie houses around the country.

One small neighborhood in the heart of Los Angeles became most closely associated with the burgeoning new industry: Hollywood.

By 1915, after a few years of failed lawsuits (and one imagines a fair number of temper-tantrums), Thomas Edison admitted defeat and dissolved his Motion Picture Patents Company.

In the heyday of those early years, some of those larger studios decided the best way to ensure an audience for their films was to own the theaters as well. They built extravagant movie palaces in large market cities, and hundreds more humble theaters in small towns, effectively controlling all aspects of the business: production, distribution and exhibition. In business terms that’s called vertical integration . It’s a practice that would get them in a lot of trouble with the U.S. government a couple of decades later, but in the meantime, it meant big profits with no end in sight.

Then, in 1927, everything changed.

Warner Bros. was a family-owned studio run by five brothers and smaller than some of the other larger companies like Universal and MGM. But one of those brothers, Sam, had a vision. Or rather, an ear. Up to that point, cinema was still a silent medium. But Sam was convinced that sound, and more specifically, sound that was synchronized to the image, was the future.

And almost everyone thought he was crazy.

It seems absurd now, but no one saw any reason to add sound to an already perfect, and very profitable, visual medium. What next? Color? Don’t be ridiculous…

Fortunately, Sam Warner persisted, investing the company’s profits into the technology required to not only record synchronized sound, but to reproduce it in their movie theaters around the country. Finally, on October 6th, 1927, Warner Bros. released The Jazz Singer , the first film to include synchronized dialog.

Spoiler alert: It was a HUGE success. Unfortunately, Sam Warner didn’t live to see it. He died of a brain infection on October 5th, the day before the premiere.

Suddenly, every studio was scrambling to catch up to Warner Bros. That meant a massive capital investment in sound technology, retrofitting production facilities and thousands of movie theaters. Not every production company could afford the upgrade, and many struggled to compete in the new market for films with synchronized sound. And just when it seemed like it couldn’t get worse for those smaller companies, it did. In October of 1929, the stock market crashed, plunging the nation into the Great Depression. Hundreds of production companies closed their doors for good.

At the start of the 1930s, after this tremendous consolidation in the industry, eight major studios were left standing: RKO Pictures, Paramount, MGM, Fox, Warner Bros., Universal Pictures, Columbia Pictures and United Artists. Five of those – RKO, Paramount, MGM, Fox and Warner Bros. – also still owned extensive theater chains (aka vertical integration ), an important source of their enormous profits, even during the Depression (apparently movies have always been a way to escape our troubles, at least for a couple of hours). But that didn’t mean they could carry on with business as usual. They were forced to be as efficient as possible to maximize profits. Perhaps ironically, this led to a 20-year stretch, from 1927 to 1948, that would become known as The Golden Age, one of the most prolific and critically acclaimed periods in the history of Hollywood.

THE GOLDEN AGE

The so-called Golden Age of Hollywood was dominated by those eight powerful studios and defined by four crucial business decisions. [1] First and foremost, at least for five of the eight, was the emphasis on vertical integration. By owning and controlling every aspect of the business, production, distribution and exhibition, those companies could minimize risk and maximize profit by monopolizing the screens in local theaters. Theatergoers would hand over their hard-earned nickels regardless of what was playing, and that meant the studios could cut costs and not lose paying customers. And even for those few independent theater chains, the studios minimized risk through practices such as block booking and blind bidding . Essentially, the studios would force theaters to buy a block of several films to screen (block booking), sometimes without even knowing what they were paying for (blind bidding). One or two might be prestige films with well-known actors and higher production values, but the rest would be low-budget westerns or thrillers that theaters would be forced to exhibit. The studios made money regardless.

The second crucial business decision was to centralize the production process. Rather than allow actual filmmakers – writers, directors, actors – to control the creative process, deciding what scripts to develop and which films to put into production, the major studios relied on one or two central producers . At Warner Bros. it was Jack Warner and Darryl Zanuck. At RKO it was David. O. Selznick. And at MGM it was Louis B. Mayer and 28 year-old Irving Thalberg.

Thalberg would become the greatest example of the central producer role, running the most profitable studio throughout the Golden Age. Thalberg personally oversaw every production on the MGM lot, hiring and firing every writer, director and actor, and often taking over as editor before the films were shipped off to theaters. And yet, he shunned fame and never put his name on any of MGM’s productions. Always in ill-health, perhaps in part because of his inhuman workload, he died young, in 1936, at age 37.

The third business decision that ensured studios could control costs and maximize profits was to keep the “talent” – writers, directors and actors – on low-cost, iron-clad, multi-year contracts. As Hollywood moved into the Golden Age, filmmakers – especially actors – became internationally famous. Stardom was a new and exciting concept, and studios depended on it to sell tickets. But if any one of these new global celebrities had the power to demand a fee commensurate with their name recognition, it could bankrupt even the most successful studio. To protect against stars leveraging their fame for higher pay, and thus cutting in on their profits, the studios maintained a stable of actors on contracts that limited their salaries to low weekly rates for years on end no matter how successful their films might become. There were no per-film negotiations and certainly no profit sharing. And if an actor decided to sit out a film or two in protest, their contracts would be extended by however long they held out. Bette Davis, one of the biggest stars of the era, once fled to England to escape her draconian contract with Warner Bros. Warner Bros. sued the British production companies that might employ her and England sent her back. These same contracts applied to writers and directors, employed by the studio as staff, not the freelance creatives they are today. It was an ingenious (and diabolical) system that meant studios could keep their production costs incredibly low.

The fourth and final crucial business decision that made the Golden Age possible was the creative specialization, or house style , of each major studio. Rather than try to make every kind of movie for every kind of taste, the studios knew they needed to specialize, to lean into what they did best. This decision, perhaps more than any of the others, is what made this period so creatively fertile. Despite all of the restrictions imposed by vertical integration, central producers, and talent contracts, the house style of a given studio meant that all of their resources went into making the very best version of certain kind of film. For MGM, it was the “prestige” picture. An MGM movie almost always centered on the elite class, lavish set designs, rags to riches stories, the perfect escapist, aspirational content for the 1930s. For Warner Bros. it was the gritty urban crime thriller: Little Caesar (1931), The Public Enemy (1931), The Maltese Falcon (1941). They were cheap to make and audiences ate them up. Gangsters, hardboiled detectives, femme fatales, these were all consistent elements of Warner Bros. films of the period. And for Universal, it was the horror movie:

Frankenstein (1931), Dracula (1931), The Mummy (1932), all of them Universal pictures (and many of them inspired by the surreal production design of German Expressionist films like The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari ).

But the fun and profits couldn’t last forever.

Three important events conspired to bring an end the reign of the major studios and the Golden Age of Hollywood.

First, in 1943, Olivia de Havilland, a young actress known for her role as Melanie in Gone with the Wind (1939), sued Warner Bros. for adding six months to her contract, the amount of time she had been suspended by the studio for refusing to take roles she didn’t want. She wasn’t the first Hollywood actor to sue a studio over their stifling contracts. But she was the first to win her case. The court’s decision in her favor set a precedent that quickly eroded the studios’ power over talent. Soon actors became freelance performers, demanding fees that matched their box office draw and even profit participation in the success of their films. All of which took a sizeable chunk out the studios’ revenue.

Then, in 1948, the U.S. government filed an anti-trust case against the major studios, finally recognizing that vertical integration constituted an unfair monopoly over the entertainment industry. The case went to the Supreme Court and in a landmark ruling known as The Paramount Decision (only because Paramount was listed first in the suit), the court ordered that all of the major studios sell off their theater chains and outlawed the practices of block booking and blind bidding. It was a financial disaster for the big studios. No longer able to shovel content to their own theater chains, studios had to actually consider what independent theaters wanted to screen and what paying audiences wanted to see. The result was a dramatic contraction in output as studios made fewer and fewer movies with increasingly expensive, freelance talent hoping to hit the moving target of audience interest.

And then it got worse.

In the wake of World War II, just as the Supreme Court was handing down The Paramount Decision, the television set was quickly becoming a common household item. By the end of the 1940s and into the 1950s, the rise of television entertainment meant fewer reasons to leave house and more reasons for the movie studios to panic. Some of them, like MGM, realized there was money to be made in licensing their film libraries to broadcasters. And some of them, like Universal, realized there was money to be made in leasing their vast production facilities to television producers. But all of them knew it was an end of an era.

THE NEW HOLLYWOOD

The end of the Golden Age thrust Hollywood into two decades of uncertainty as the major studios struggled to compete with the new Golden Age of Television and their own inability to find the pulse of the American theater-going public. There were plenty of successes. MGM’s focus on musicals like Singin’ in the Rain (1952) and historical extravaganzas like Ben Hur (1959), for example, helped keep them afloat. (Though those came too late for Louis B. Mayer, one of the founders of the studio. He was fired in 1951.) But throughout the 50s and 60s, studios found themselves spending more and more money on fewer and fewer films and making smaller and smaller profits. To make matters worse, many of these once family-owned companies were being bought up by larger, multi-national corporations. Universal was bought out by MCA (a talent agency) in 1958. Paramount by Gulf Western in 1966. And Warner Bros. by Seven Arts that same year. These new parent companies were often publicly traded with a board of directors beholden to shareholders. They expected results.