The future of human behaviour research

Affiliations.

- 1 Department of Political Science, Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA. [email protected].

- 2 School of Communication and Digital Media Research Centre (DMRC), Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, Queensland, Australia. [email protected].

- 3 Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for Automated Decision-Making and Society (ADM+S), Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. [email protected].

- 4 Department of Neuroscience and Padova Neuroscience Center (PNC), University of Padova, Padova, Italy. [email protected].

- 5 Venetian Institute of Molecular Medicine (VIMM), Padova, Italy. [email protected].

- 6 Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, USA. [email protected].

- 7 Microsoft Research New York, New York, NY, USA. [email protected].

- 8 École Normale Supérieure, Paris, France. [email protected].

- 9 Department of Economics, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA. [email protected].

- 10 Department of Human Behavior, Ecology, and Culture, Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Leipzig, Germany. [email protected].

- 11 Department of Psychology, University of California at Berkeley, Berkeley, CA, USA. [email protected].

- 12 American University of Beirut, Beirut, Lebanon. [email protected].

- 13 Department of Global Development, College of Agriculture and Life Sciences and Cornell Atkinson Center for Sustainability, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, USA. [email protected].

- 14 Department of Management, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, China. [email protected].

- 15 Center for Social and Environmental Systems Research, Social Systems Division, National Institute for Environmental Studies, Tsukuba, Japan. [email protected].

- 16 State Key Laboratory of Brain and Cognitive Sciences and Laboratory of Neuropsychology and Human Neuroscience, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, China. [email protected].

- 17 WHO Collaborating Centre for Infectious Disease Epidemiology and Control, School of Public Health, LKS Faculty of Medicine, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, China. [email protected].

- 18 Laboratory of Data Discovery for Health, Hong Kong Science and Technology Park, Hong Kong, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, China. [email protected].

- 19 Heinz College of Information Systems and Public Policy, Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, PA, USA. [email protected].

- 20 Department of Experimental Psychology, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK. [email protected].

- 21 Oxford Centre for Human Brain Activity, Wellcome Centre for Integrative Neuroimaging, Department of Psychiatry, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK. [email protected].

- 22 CORE - Copenhagen Research Centre for Mental Health, Mental Health Centre Copenhagen, Copenhagen University Hospital, Copenhagen, Denmark. [email protected].

- 23 Department of Clinical Medicine, Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark. [email protected].

- 24 Department of Economics, School of Business and Economics, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. [email protected].

- 25 Complex Human Data Hub, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. [email protected].

- 26 ODID and SAME, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK. [email protected].

- 27 School of Public Policy, Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta, GA, USA. [email protected].

- 28 Centre of Excellence FAIR, NHH Norwegian School of Economics, Bergen, Norway. [email protected].

- 29 GESIS - Leibniz Institute for the Social Sciences, Köln, Germany. [email protected].

- 30 RWTH Aachen University, Aachen, Germany. [email protected].

- 31 Complexity Science Hub Vienna, Vienna, Austria. [email protected].

- PMID: 35087189

- DOI: 10.1038/s41562-021-01275-6

- Anthropology / trends

- Artificial Intelligence / trends

- Behavioral Research / trends*

- Social Sciences / trends*

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Learning, the Sole Explanation of Human Behavior: Review of The Marvelous Learning Animal: What Makes Human Nature Unique

James s macdonall.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Corresponding author.

Collection date 2016 May.

Seemingly everyone is interested in understanding the causes of human behavior. Yet many scientists and the general public embrace causes of behavior that have logical flaws. Attributing behavior to mental events, emotions, personality, or abnormal personality, typically, is committing one of a number of common errors, such as reification, circular reasoning, or nominal fallacies (Schlinger & Poling, 1998 ). An increasingly frequent error is embracing genetic explanations of behavior in the absence of an identified gene. Similarly, explaining behavior in terms of brain structure or function fails to ask what caused that brain structure or function to develop or function in a particular way.

As Arthur Staats ( 2012 ) notes in his valuable book The Marvelous Learning Animal: What Makes Human Nature Unique , unfortunately, such flawed explanations have prospered at the expense explanations based on learning mechanisms. Consequently, many behavior analysts would like to see a book that uses non-technical language to clearly delineate the limitations of explanations based on mind, brain, genes, and personality. Such a book would clearly describe how human behavior (both typical and problematic) can be understood in terms of learning principles, how myriad daily interactions from right after birth make us who we are, how the relevant behavioral research progresses, how interventions are developed based on the research, and how these interventions are subject to research demonstrating their effectiveness. The book would also describe the proper role of genetics and brain structure and function in an understanding of behavior. Perhaps no single volume can do all of these things equally well, The Marvelous Learning Animal is a useful complement to existing works with which behavior analysts may already be familiar (e.g., Schneider, 2012 ; Skinner, 1953 ).

The Great Scientific Error

Attributing causes of behavior to mind, brain, genes, personality, intelligence, abnormal personality, or genetics Staats calls the Great Scientific Error. According to Staats, learning was overlooked as a cause of behavior because early behaviorists did not develop research programs examining learning principles in complex human behavior, behavior occurring outside the laboratory under natural contingencies. Behaviorisms’ total rejection of “personality, intelligence, attitudes, interests or psychological measurement” (p. 33) exacerbated the problem in two ways. First, many in the general population rejected behavioral views because behaviorists rejected these concepts that seemed self-evidently true. Second, behaviorists did not examine the contingencies producing the behaviors subsumed under these labels. Research on reading and language shows the importance of identifying the natural contingencies in development (Hart & Risley, 1995 ; Moerk, 1990 ). Thus, Staats calls for a new learning paradigm that extends from the genetic basis of learning principles through how these learning principles function in complex human behavior. Given the methodological advances in genetics and neuroscience, Skinner, were he alive to see it, may well have agreed with this approach.

The Human Animal

Homo sapiens , according to Staats, are unique in two ways. First, humans have considerable sensitivity to a wide range of stimuli (e.g., light, sound, heat, and tactile). Within each stimulus modality, humans are not the most sensitive (e. g., many birds see better than we do). Some species can sense stimuli that humans do not sense (e.g., honey bees discriminate polarized light). However, we are the only species with very good sensitivity in many modalities. Similarly, we have a diversified motor system. True, other species have as much or more strength or fine control of specific motor systems (e.g., cats can jump further and with greater accuracy than we can jump). But we are the only species that has very good control of a wide variety of motor systems (e. g., facial muscles, hand/finger muscles, and arm and leg muscles).

Second, diverse sensory and motor systems need a brain that not only relays “messages” from sensory receptors to muscle fibers but also integrates the inputs from diverse sensory receptors along with neural results of prior experience producing complex sets of outputs to muscle fibers (what normally is called learning). It is estimated that humans have upwards of 100 billion neurons and on average several thousand synaptic connections for each neuron (Kolb, Gibb, & Robinson, 2001 ). This very large brain, interacting with our diverse sensory and motor systems, is what makes humans unique.

Child Development and the Missing Link

The Marvelous Learning Animal is informed by Staats’ own scholarly career, in which he focused on examining contingencies of naturally occurring behavior. Once Staats identified what he hypothesized were the critical contingencies, he would manipulate them to see if he could speed development and thereby demonstrate their importance. Throughout The Marvelous Learning Animal , Staats divides behavior and its development, for convenience, into three broad areas: emotion-motivation, sensory-motor, and language-cognitive. Despite these labels, the analysis is thoroughly behavioral; there are no hidden behaviors or processes. In all of these domains, Staats argues, maturation is a function of physical growth interacting with natural contingencies, which change as a child’s behavior changes. In Staats’ world view, there is no separate process of child development.

Staats rejects genetics (except for those that program for unconditioned reflexes) and epigenetics as the cause of any behavior. Much of the evidence supporting genetic and epigenetic accounts takes the form of documenting that behavioral disruption results when genetic mechanisms are perturbed. Missing from these accounts, however, is an explanation of how, in relevant disorders, changes in genes affect learning. Thus, the behavior analyst’s task is to identify how a defective gene disrupts learning. In Staats’ view, that knowledge combined with knowledge of the natural contingencies that support normal development allow a complete understanding and effective interventions to minimize or eliminate these so-called genetic or epigenetic disorders.

An example from medicine illustrates the general spirit of this approach and its benefits. Phenylketonuria is a genetic disorder that invariably kills young children with a particular defective gene. Investigators identified the defective gene, but did not stop there. They also found that the non-defective version of the gene produces enzymes necessary for metabolizing phenylalanine, an amino acid toxic to neurons at high doses. A diet with limited phenylalanine, supplemental amino acids, and other nutrients prevents phenylalanine from accumulating and killing young children (Macleod & Ney, 2010 ), even though the genetic defect remains.

Identifying the natural contingencies in development is an exciting research area for behavior analysts. The working hypothesis, of course, is that behavior putatively caused by natural selection can instead be understood by prior experiences. For example, many consider exploratory behaviors of infants to result from genetics, as this quote from Skinner (1948, reprinted 1975 ) might be taken to imply: “No one asks how to motivate a baby. A baby naturally explores everything it can get at….” (p. 144). Staats takes the view that exploratory behaviors, and by implication differences in exploratory behaviors, result from natural reinforcement, that is, changes in the environment produced by exploring as when a baby touches an object it may rattle. If natural selection is not responsible for individual differences in behavior, then it follows that these differences result from differences in learning experiences. This is not to say that there are no intraspecies differences in behavior potential. Humans, for instance, evolved genetic and brain mechanisms that are specific to language, but critically it is early experiences that result in language acquisition and language differences across individuals.

As too few behavior analysts have recognized (e.g., Bijou & Baer, 1961 ; Schlinger, 1995 ), only a detailed examination of early experiences can identify the role of environment in typical development, and by extension in atypical development. In the case of language, research suggests a clear role for early experience in language acquisition. For instance, the more children are exposed to verbal interactions, the greater their language competences’ (Hart & Risley, 1995 ; Moerk, 1990 ). This work has inspired a spate of programs to increase the number of words heard by young children with, or at risk for, language problems, with the goal of nudging language development toward a more normal developmental trajectory (e.g., Suskind & Suskind, 2015 ). It is not yet clear whether these programs adequately reproduce the natural contingencies identified in Moerk ( 1990 ) and Hart & Risley ( 1995 ), but the general approach is consistent with what Staats’ advocates: using natural contingencies as the inspiration for early intervention strategies for children who are falling behind developmental norms.

Crucial Concepts in Human Development

In explaining development, Staats assigns an important role to classical and operant conditioning, but he proposes that complex human behavior is best understood in terms of behavior repertoires and cumulative learning . These two processes, according to Staats, are unique to humans and, when combined with basic learning processes, account for all human behavior.

For Staats, behavior repertoires are complex sets of related stimulus-control relations. He gives the example of a reading repertoire that was built in a dyslexic child via 64,000 trials with a variety of stimulus-control relations involving letters, words, etc. (Staats & Butterfield, 1965 .). Staats identified a large number of these repertoires and their interrelations. Such a reading repertoire, combined with sensory-motor development, can promote a writing repertoire. The reading repertoire may combine with a repertoire for following spoken instructions to allow individuals to follow written instructions, or combined with a sensory-motor repertoire allowing individuals to write instructions. Individual behaviors can be part of several repertoires, and repertoires can be hierarchical, with bigger repertoires comprised, in part, of smaller repertoires. One important goal of behavioral research, in Staats’ view, is to identifying relations among different repertoires and how contingencies influence these repertoires and their interrelations.

Behavior repertoires result in cumulative learning. In mastery of a repertoire, behaviors learned later are acquired more quickly than previously learned behaviors. For example, children learning to print letters late in the alphabet only require one fourth the trials compared to learning to print the letter A . Additionally, mastering one repertoire can make it easier to master a subsequent repertoire. For example, a sound-imitation repertoire combined with suitable prompts produces a word-imitation repertoire that promotes faster language learning. While it may be uncontroversial among behavior analysts to claim that behavior consists of many repertoires and learning one repertoire facilitates learning others, there are few systematic research programs to identify these repertoires, their components, and the contingencies that produce them and establish and maintain their relation to other repertoires.

Staats speculates that cumulative learning influenced human cultural development. Cultural transmission of learning in effect allows one individual’s repertoire to build upon another’s. As one generation masters a repertoire the succeeding generation can master that repertoire faster and is able to expand that repertoire or beginning learning a repertoire new to the group. Staats gives the example of artistic repertoires becoming more sophisticated across generations. Unfortunately, Staats is somewhat vague on the specific mechanisms driving such changes, implying without sufficient explanation that the cumulative learning of a culture’s individual members somehow translates to intergenerational effects (Skinner, 1984 , was similarly vague in his account of cultural selection). Staats also places great emphasis on contingency-shaped behavior in his account of cultural development and, surprisingly, omits any function for rule-governed behavior.

From a behavior analytic perspective, a further limitation of Staats’ account is uncertainty regarding whether behavior repertoires and cumulative learning, as Staats invokes them, qualify as new concepts. By claiming that these phenomena are uniquely human Staats certainly suggests so, but nevertheless behavior analysts will find much that feels familiar in his use of them. For instance, Staats’ analysis of behavioral repertoires and their complex interrelationships brings to mind how reinforcers organize behavior into operants and how the resulting class of responses may not be identical to the class of reinforced responses (Catania, 2013 ). His description of cumulative learning may relate to learning sets (Harlow, 1949 ), pivotal response (Bryson, Koegel, Koegel, Openden, Smith, & Nefdt, 2007 ), and behavior cusps (Rosales-Ruiz & Baer, ( 1997 ), although Staats is silent on these possible connection. In the end, readers will be left to ponder important questions that are suggested by, but not answered in, The Marvelous Learning Animal , not the least of which concerns what sort of research program may be imagined to test Staats’ ideas.

Learning Human Nature

With the preceding as foundational knowledge, Staats addresses specific types of behavior that supposedly are explained by the Great Scientific Error. For example, intelligence tests subsume a variety of repertoires, such as naming, counting, instruction following, and imitating. Differences in intelligence test scores must therefore be interpreted as differences in acquisition of these behavioral repertoires, not differences in an internal entity called intelligence. Staats points out that intelligence test scores predict school performance not because they describe inherent ability but rather because many of the behavior repertoires required for success in school are assessed in intelligence tests. This leads naturally to the proposal for an analysis of the repertoires comprising what we call intelligent behavior, which would include research on the natural contingencies producing these repertoires and, eventually, attempts to foster development by systematically implementing those contingencies.

Behavior analysts will correctly anticipate that Staats proposes that abnormal experiences produce abnormal behaviors. His examples of problematic early childhood behaviors—including tantrums, yelling, hitting, defiance, and so forth—are familiar, as is his suggestion that how caregivers respond to these behaviors influences whether or not they continue and become more severe. These unfortunate natural contingencies produce behavioral repertories that may eventually qualify the individual for a “psychiatric” diagnosis, and once the diagnosis is in place, it elicits sympathy or fear that may only exacerbate caregiver acquiescence to problem behavior. Within the context of autism and a few other disorders, Staats’ recommendation for action is equally familiar. He prescribes clearly identifying the relevant behavior repertoires, analyzing the abnormal contingencies which produce those repertoires and exploring how these repertoires may, through cumulative learning, produce additional problem repertoires. A particular contribution of The Marvelous Learning Animal is to apply the same approach to understanding the development of dyslexia, paranoid schizophrenia, paraphilias, depression, and other problems less frequently addressed by applied behavior analysts. Staats holds steadfastly to his environmental perspective even in cases where biological damage or genetic abnormalities typically are held to cause the disorder (e.g., Down’s syndrome).

Human Evolution and Marvelous Learning

There is much more in Staats’ analysis that is worthy of consideration by behavior analysts, including his assertion that cumulative learning has been an important influence in human natural selection. As Staats notes, those in the field of human evolution are beginning to reach a similar conclusion (Diamond, 1992 ; Gould, 1977 ; Jablonka & Lamb, 2005 ), although Staats’ account is interesting for the emphasis it places on selection for verbal abilities and how verbal abilities influence selection. Critical thinking is required to examine ways in which the account deviates from those of behavior analysts (see Skinner, 1984 , in reinforcement as a mechanism of natural selection) and evolutionary biologists. In the latter case, Staats’ hardest-to-swallow view, namely that natural selection provides all humans with equal learning abilities because variation in learning ability is selected out. This notion is at odds with the widely accepted notion that natural selection is possible only when populations contain variability (Dawkins, 1976 ).

A Human Paradigm

It is refreshing to see an environment-centric alternative to the Great Scientific Error, and behavior analysts will appreciate Staats’ panache in placing learning at the center of all explanations of human behavior. They also will be interested in his conclusion that radical changes are required in the basic science of human behavior and the application of that science to clinical practice. In Staats’ view, the revised science needs to know much more about how learning and biology combine to produce behavior, which implies relying on techniques (e.g., brain imaging technology, genetic assays) to understand the interrelatedness of learning and biology. Many behavior analysts will sympathize with Staats’ proposition that the field of child development needs to be almost entirely restarted, using sophisticated observational methods required to identify the natural contingencies in development. Perhaps less intuitive, and therefore more challenging, to behavior analysts is Staats’ implication that, ultimately, the study of human behavior can only proceed with a proper study of development as he defines it. For example, an infant lies on their stomach pushes up with their arms which raises their head allowing them to see objects hidden behind other objects. If seeing a new view is reinforcing, or seeing objects previously followed by reinforcers is reinforcing, then infants will continue to push up. As they raise their head further above the surface, more items come into view. Eventually the standing infant may lean toward a favored object. They move a foot, preventing themselves from falling, bringing them closer to a reinforcing object. The first proto step has been naturally reinforced. Although, non-behavior analysts have collected data supporting aspects of this analysis, they did not include the functions of behaviors as walking developed (Adolph, Cole, Komati, Garciagurre, Badaly, Lingemanm, Chan, & Sotsky, 2012 ).

A central irony of behavior analysis is that its adherents (beginning with Skinner, e.g., 1953 ) have maintained that complex environmental relations account for the diversity of human behaviors, while their own work carefully analyzed only a limited range of interesting behaviors. The Marvelous Learning Animal challenges behavior analysts (and other readers) to imagine what a behavior science would look like if it thoroughly examined all of those interesting behaviors. In this regard, it matters little if along the way Staats commits a variety of transgressions such as failing to fully explain every concept, possibly playing fast and loose with natural selection, relying on lay terms that carry mentalistic connotations (this is, after all, a popular press book), and occasionally speaking ill of radical behaviorism.

These details should not be allowed to distract from the book’s essential challenge, which is to ask those who would advance environmental experience as the primary engine of behavior development to develop the science that is needed to test and support such an account. Staats delivers an analysis of complex human behavior that is indisputably behavioral and often consistent with a radical behavioral view. Where the analysis diverges from radical behaviorism as it has traditionally been practiced, it most often offers expansion rather than contradiction and thereby provides a stimulating basis for further inquiry.

Acknowledgments

I thank Bob Allen for his helpful comments on an earlier version of this review. All the remaining shortcomings result from my behavior.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

The preparation of this manuscript was not funded by any organization. I have no ethical conflicts in preparing this manuscript.

- Adolph KE, Cole WG, Komati M, Garciagurre JS, Badaly D, Lingemanm JM, et al. How do you learn to walk? Thousands of steps and dozens of falls per day. Psychological Science. 2012;23:1387–1394. doi: 10.1177/0956797612446346. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bijou SW, Baer DM. Child development: Vol. 1: a systematic and empirical theory. New York: Prentice-Hall; 1961. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bryson SE, Koegel LK, Koegel RL, Openden D, Smith IM, Nefdt N. Large scale dissemination and community implementation of pivotal response treatment: program description and preliminary data. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities. 2007;32:142–153. doi: 10.2511/rpsd.32.2.142. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Catania AC. Learning. Cornwall-on-Hudson: Sloan Publishing; 2013. [ Google Scholar ]

- Dawkins, R. (1976). The selfish gene. Oxford University Press.

- Diamond J. The third chimpanzee: the evolution and future of the human animal. New York: Harper Perennial; 1992. [ Google Scholar ]

- Gould, (1977). Ever since Darwin: reflections on natural history. W. W. Norton.

- Harlow HF. The formation of learning sets. Psychological Review. 1949;56(1):51–65. doi: 10.1037/h0062474. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hart M, Risley T. Meaningful differences in the everyday experiences of young American children. Baltimore: Brookes Publishing; 1995. [ Google Scholar ]

- Jablonka, Lamb . Evolution in four dimensions. Cambridge: MIT Press; 2005. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kolb, B., R. Gibb, & T. E. Robinson. (2001). Brain plasticity and behavior. In, J. Lerner & A. E. Alberts (Eds.), Current directions in developmental psychology, Prentice–Hall.

- Macleod EL, Ney DM. Nutritional management of phenylketonuria. Annales Nestlé (English ed.) 2010;68:58–69. doi: 10.1159/000312813. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Moerk EL. Three-term contingency patterns in mother-child verbal interactions during first-language acquisition. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1990;54:293–305. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1990.54-293. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rosales-Ruiz J, Baer DM. Behavioral cusps: a developmental and pragmatic concept for behavior analysis. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1997;30:533–544. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1997.30-533. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Schlinger HD., Jr . A behavior analytic view of child development. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; 1995. [ Google Scholar ]

- Schlinger HD, Poling A. Introduction to scientific psychology. New York: Plenum; 1998. [ Google Scholar ]

- Schneider, S. (2012). Science of consequences: how they affect genes, change the brain, and impact our world. Prometheus Books.

- Skinner BF. Science and human behavior. New York: McMillan; 1953. [ Google Scholar ]

- Skinner BF. Walden two. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing; 1975. [ Google Scholar ]

- Skinner BF. The selection of behavior. Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 1984;7:477–481. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X0002673X. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Staats AW. The marvelous learning animal: what makes human behavior unique. Amherst: Prometheus Books; 2012. [ Google Scholar ]

- Staats AW, Butterfield WH. Treatment of non-reading in a culturally-deprived juvenile delinquent: an application of reinforcement principles. Child Development. 1965;36:925–942. doi: 10.2307/1126934. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Suskind, D. & Suskind, B. (2015). Thirty million words: building a child’s brain. Dutton.

- View on publisher site

- PDF (245.0 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

Largest Quantitative Synthesis to Date Reveals What Predicts Human Behavior and How to Change It

Prof. Dolores Albarracín and her team dug through years of research on the science behind behavior change to determine the best ways to promote changes in behavior.

By Hailey Reissman

Pandemics, global warming, and rampant gun violence are all clear lessons in the need to move large groups of people to change their behavior. When a crisis hits, researchers, policymakers, health officials, and community leaders have to know how best to encourage people to change en masse and quickly. Each crisis leads to rehashing the same strategies, even those that have not worked in the past, due to the lack of definitive science of what interventions work across the board combined with well intended but erroneous intuitions.

To produce evidence on what determines and changes behavior, Professor Dolores Albarracín and her colleagues from the Social Action Lab at the University of Pennsylvania undertook a review of all of the available meta-analyses — a synthesis of the results from multiple studies — to determine what interventions work best when trying to change people’s behavior. What results is a new classification of predictors of behavior and a novel, empirical model for understanding the different ways to change behavior by targeting either individual or social/structural factors.

A paper published today in Nature Reviews Psychology reports that the strategies that people assume will work — like giving people accurate information or trying to change their beliefs — do not. At the same time, others like providing social support and tapping into individuals’ behavioral skills and habits as well as removing practical obstacles to behavior (e.g., providing health insurance to encourage health behaviors) can have more sizable impacts.

“Interventions targeting knowledge, general attitudes, beliefs, administrative and legal sanctions, and trustworthiness — these factors researchers and policymakers put so much weight on — are actually quite ineffective,” says Albarracín. “They have negligible effects."

Unfortunately, many policies and reports are centered around goals like increasing vaccine confidence (an attitude) or curbing misinformation. Policymakers must look at evidence to determine what factors will return the investment, Albarracín says.

Co-author Javier Granados Samayoa, the Vartan Gregorian Postdoctoral Fellow at the Annenberg Public Policy Center, has noticed researchers’ tendency to target knowledge and beliefs when creating behavior change interventions.

“There's something about it that seems so straightforward — you think x and therefore you do y . But what the literature suggests is that there are a lot of intervening processes that have to line up for people to actually act on those beliefs, so it’s not that easy,” he says.

Targeting Human Behavior

To change behaviors, intervention researchers focus on the two types of determinants of human behavior: individual and social-structural. Individual determinants encompass personal attributes, beliefs, and experiences unique to each person, while social-structural determinants encompass broader societal influences on people, like laws, norms, socioeconomic status, social support, and institutional policies.

The researchers’ review explored meta-analyses of experiments in which specific social-structural determinants or specific individual determinants were tested for their ability to change behavior. For example, a study might test how learning more about vaccination might encourage vaccination (knowledge) or how reductions in health insurance copayment charges might encourage medication adherence (access).

These meta-analyses encompassed eight individual and eight social-structural determinants — part of the original classification made by the authors.

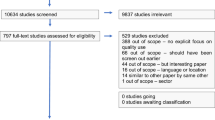

The results from the research are presented in the following three figures, which pertain to a. all behaviors analyzed, b. only health behaviors, and c. only environmental behaviors.

The figures present interventions with individual targets on the left, and interventions with social/structural targets on the right. For each determinant, the figures show whether the effects has been shown to be negligible, small, medium or large.

Individual Determinants

The analyses researchers conducted showed that what are often assumed to be the most effective individual determinants to target with interventions were not the most effective. Knowledge (like educating people about the pros of vaccination), general attitudes (like implicit bias training), and general skills (like programs designed to encourage people to stop smoking) had negligible effects on behavior.

What was effective at an individual level was targeting habits (helping people to stop or start a behavior), behavioral attitudes (having people associate certain behaviors as being “good” or “bad”), and behavioral skills (having people learn how to remove obstacles to their behavior).

Social-Structural Determinants

The researchers also found that what are often assumed to be the most effective social-structural persuasive strategies were not. Legal and administrative sanctions (like requiring people to get vaccinated) and interventions to increase trustworthiness — justice or fairness within an organization or government entity — (like providing channels for voters to voice their concerns) had negligible effects on behavior.

Norms and forms to monitor and incentivize behavior had some effects, albeit small. What was most effective was focusing on targeting access (like providing flu vaccinations at work) or social support (facilitating groups of people who help one another to meet their physical activity goals).

Granados Samayoa says that knowing which behavior change interventions work at which levels will be especially crucial in the face of growing health and environmental challenges.

“When faced with massive problems like climate change, policy makers and other leaders have this desire to do something to change people's behavior for the better,” says Samayoa. “Our study provides valuable insights. Our research can inform future interventions and create programs that are actually effective, not just what people assume is effective.

Albarracín is glad policymakers will have this resource now.

“Before this study, analyses of behavior change efforts were limited to one domain, whether that was environmental science or public health. By looking at research across domains, we now have a clearer picture of how to encourage behavior change and make a difference in people’s lives,” she says.

“Our research provides a map for what might be effective even for behaviors nobody has studied. Just like masking because a critical behavior during the pandemic but we had no research on masking, a broad empirical study of intervention efficacy can guide future efforts for an array of behaviors we have not directly studied but that need to be promoted during a crisis.”

“Determinants of Behaviour and Their Efficacy As Targets of Behavioural Change Interventions” was published in Nature Reviews Psychology and authored by Dolores Albarracín, Bita Fayaz-Farkhad, and Javier Granados Samayoa. The research was funded by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants R01MH132415, R01 AI147487, DP1 DA048570, R01 MH114847, and NSF 2031972 to Dolores Albarracín, and by the Annenberg Foundation Endowment to the Division of Communication Science at the Annenberg Public Policy Center.

About the Social Action Lab

The Social Action Lab is a group of experts and trainees in psychology, communication, and economics who seek to understand the fundamentals of social behavior and apply this knowledge to the solution of social and health problems. The lab is led by Dolores Albarracín, a Penn Integrates Knowledge Professor and Director of the Division of Communication Science in Annenberg Public Policy Center. She holds appointments in the Annenberg School for Communication, the Department of Psychology in the School of Arts & Sciences, the School of Nursing, and the Wharton School. The other two authors are Bita Fayaz-Farkhad, who is Assistant Research Professor in the Annenberg School for Communication, and Javier Granados Samayoa, the Vartan Gregorian Postdoctoral Fellow of the Annenberg Public Policy Center.

- Attitudes & Persuasion

- Behavior Change

- Media Effects

- Public Health

Research Areas

- Health Communication

- Science Communication

Related News

How Fanfiction Communities in China Cope With Censorship

Researchers Use Augmented Reality to Encourage Pediatric Vaccination In Philadelphia

New Study Reveals Democrats and Republicans Vastly Underestimate the Diversity of Each Other’s Views

OPINION article

Challenges and opportunities for human behavior research in the coronavirus disease (covid-19) pandemic.

- 1 Department of General Psychology, University of Padova, Padua, Italy

- 2 Department of Brain and Behavioral Sciences, University of Pavia, Pavia, Italy

The COVID-19 pandemic is a serious public health crisis that is causing major worldwide disruption. So far, the most widely deployed interventions have been non-pharmacological (NPI), such as various forms of social distancing, pervasive use of personal protective equipment (PPE), such as facemasks, shields, or gloves, and hand washing and disinfection of fomites. These measures will very likely continue to be mandated in the medium or even long term until an effective treatment or vaccine is found ( Leung et al., 2020 ). Even beyond that time frame, many of these public health recommendations will have become part of individual lifestyles and hence continue to be observed. Moreover, it is implausible that the disruption caused by COVID-19 will dissipate soon. Analysis of transmission dynamics suggests that the disease could persist into 2025, with prolonged or intermittent social distancing in place until 2022 ( Kissler et al., 2020 ).

Human behavior research will be profoundly impacted beyond the stagnation resulting from the closure of laboratories during government-mandated lockdowns. In this viewpoint article, we argue that disruption provides an important opportunity for accelerating structural reforms already underway to reduce waste in planning, conducting, and reporting research ( Cristea and Naudet, 2019 ). We discuss three aspects relevant to human behavior research: (1) unavoidable, extensive changes in data collection and ensuing untoward consequences; (2) the possibility of shifting research priorities to aspects relevant to the pandemic; (3) recommendations to enhance adaptation to the disruption caused by the pandemic.

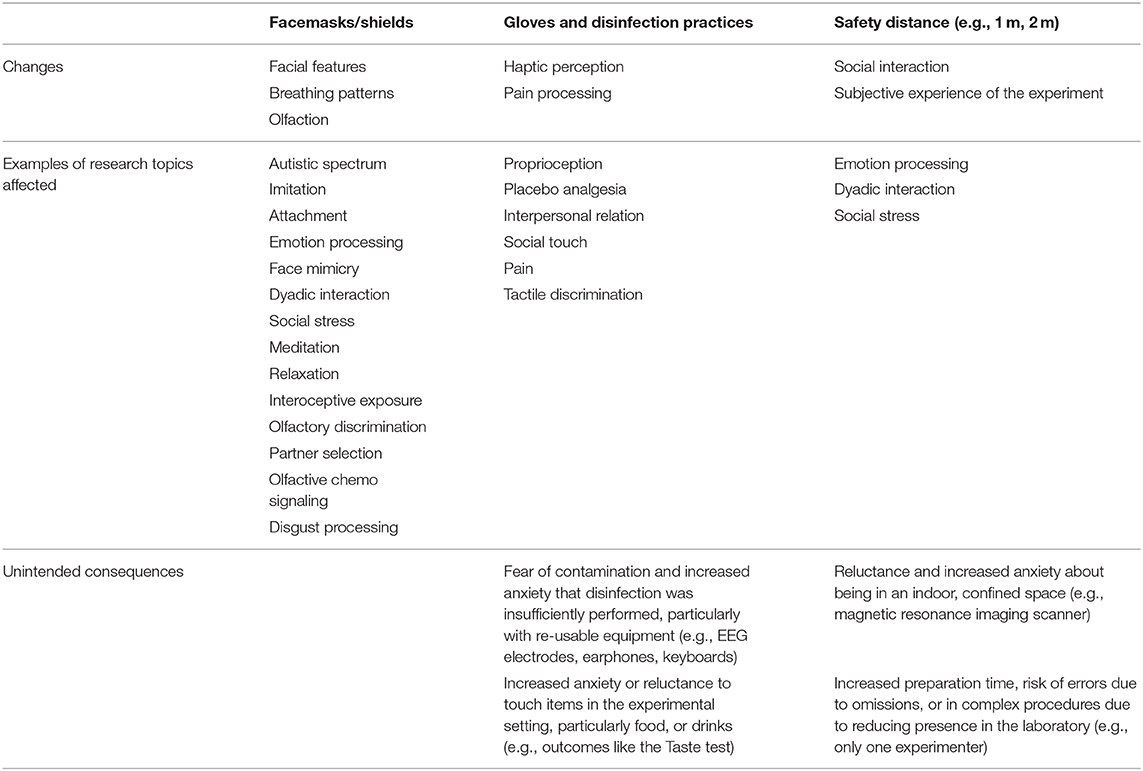

Data collection is very unlikely to return to the “old” normal for the foreseeable future. For example, neuroimaging studies usually involve placing participants in the confined space of a magnetic resonance imaging scanner. Studies measuring stress hormones, electroencephalography, or psychophysiology also involve close contact to collect saliva and blood samples or to place electrodes. Behavioral studies often involve interaction with persons who administer tasks or require that various surfaces and materials be touched. One immediate solution would be conducting “socially distant” experiments, for instance, by keeping a safe distance and making participants and research personnel wear PPE. Though data collection in this way would resemble pre-COVID times, it would come with a range of unintended consequences ( Table 1 ). First, it would significantly augment costs in terms of resources, training of personnel, and time spent preparing experiments. For laboratories or researchers with scarce resources, these costs could amount to a drastic reduction in the experiments performed, with an ensuing decrease in publication output, which might further affect the capacity to attract new funding and retain researchers. Secondly, even with the use of PPE, some participants might be reluctant or anxious to expose themselves to close and unnecessary physical interaction. Participants with particular vulnerabilities, like neuroticism, social anxiety, or obsessive-compulsive traits, might find the trade-off between risks, and gains unacceptable. Thirdly, some research topics (e.g., face processing, imitation, emotional expression, dyadic interaction) or study populations (e.g., autistic spectrum, social anxiety, obsessive-compulsive) would become difficult to study with the current experimental paradigms ( Table 1 ). New paradigms can be developed, but they will need to first be assessed for reliability and validated, which will undoubtedly take time. Finally, generalized use of PPE by participants and personnel could alter the “usual” experimental setting, introducing additional biases, similarly to the experimenter effect ( Rosenthal, 1976 ).

Table 1 . Possible consequences of non-pharmacological interventions for COVID-19 on human behavior research.

Data collection could also adapt by leveraging technology, such as running experiments remotely via available platforms, like for instance Amazon's Mechanical Turk (MTurk), where any task that programmable with standard browser technology can be used ( Crump et al., 2013 ). Templates of already-programmed and easily customizable experimental tasks, such as the Stroop or Balloon Analog Risk Task, are also available on platforms like Pavlovia. Ecological momentary assessment is another feasible option, since it was conceived from the beginning for remote use, with participants logging in to fill in scales or activity journals in a naturalistic environment ( Shiffman et al., 2008 ). Increasingly affordable wearables can be used for collecting physiological data ( Javelot et al., 2014 ). Web-based research was already expanding before the pandemic, and the quality of the data collected in this way is comparable with that of laboratory studies ( Germine et al., 2012 ). Still, there are lingering issues. For instance, for some MTurk experiments, disparities have been evidenced between laboratory and online data collection ( Crump et al., 2013 ). Further clarifications about quality, such as consistency or interpretability ( Abdolkhani et al., 2020 ), are also needed for data collected using wearables.

Beyond updating data collection practices, a significant portion of human behavior research might change course to focus on the effects of the pandemic. For example, the incidence of mental disorders or of negative effects on psychological and physical well-being, particularly across populations of interest (e.g., recovered patients, caregivers, and healthcare workers), are crucial areas of inquiry. Many researchers might feel hard-pressed to not miss out on studying this critical period and embark on hastily planned and conducted studies. Multiplication and fragmentation of efforts are likely, for instance, by conducting highly overlapping surveys in widely accessible and oversampled populations (e.g., university students). Moreover, rushed planning is bound to lead to taking shortcuts and cutting corners in study design and conduct, e.g., skipping pre-registration or even ethical committee approval or using not validated measurement tools, like ad hoc surveys. Surveys using non-probability and convenience samples, especially for social and mental health problems, frequently produce biased and misleading findings, particularly for estimates of prevalence ( Pierce et al., 2020 ). A significant portion of human behavior research that re-oriented itself to study the pandemic could result in to a heap of non-reproducible, unreliable, or overlapping findings.

Human behavior studies could also aim to inform the planning and enforcement of public health responses in the pandemic. Behavioral scientists might focus on finding and testing ways to increase adherence to NPIs or to lessen the negative effects of isolation, particularly in vulnerable groups, e.g., the elderly or the chronically ill and their caretakers. Studies could also attempt to elucidate factors that make individuals uncollaborative with recommendations from public health authorities. Though all of these topics are important, important caveats must be considered. Psychology and neuroscience have been affected by a crisis in reproducibility and credibility, with several established findings proving unreliable and even non-reproducible ( Button et al., 2013 ; Open Science Collaboration, 2015 ). It is crucial to ensure that only robust and reproducible results are applied or even proposed in the context of a serious public health crisis. For instance, the possible influence of psychological factors on susceptibility to infection and potential psychological interventions to address them could be interesting topics. However, the existing literature is marked by inconsistency, heterogeneity, reverse causality, or other biases ( Falagas et al., 2010 ). Even for robust and reproducible findings, translation is doubtful, particularly when these are based on convenience samples or on simplified and largely artificial experimental contexts. For example, the scarcity of medical resources (e.g., N-95 masks, drugs, or ventilators) in a pandemic with its unavoidable ethical conundrum about allocation principles and triage might appeal to moral reasoning researchers. Even assuming, implausibly, that most of the existent research in this area is robust, translation to dramatic real-life situations and highly specialized contexts, such as intensive care, would be difficult and error-prone. Translation might not even be useful, given that comprehensive ethical guidance and decision rules to support medical professionals already exist ( Emanuel et al., 2020 ).

The COVID-19 pandemic and the corresponding global public health response pose significant and lasting difficulties for human behavior research. In many contexts, such as laboratories with limited resources and uncertain funding, challenges will lead to a reduced research output, which might have further domino effects on securing funding and retaining researchers. As a remedy, modifying data collection practices is useful but insufficient. Conversely, adaptation might require the implementation of radical changes—producing less research but of higher quality and more utility ( Cristea and Naudet, 2019 ). To this purpose, we advocate for the acceleration and generalization of proposed structural reforms (i.e., “open science”) in how research is planned, conducted, and reported ( Munafò et al., 2017 ; Cristea and Naudet, 2019 ) and summarize six key recommendations.

First, a definitive move from atomized and fragmented experimental research to large-scale collaboration should be encouraged through incentives from funders and academic institutions alike. In the current status quo, interdisciplinary research has systematically lower odds of being funded ( Bromham et al., 2016 ). Conversely, funders could favor top-down funding on topics of prominent interest and encourage large consortia with international representativity and interdisciplinarity over bottom-up funding for a select number of excellent individual investigators. Second, particularly for research focused on the pandemic, relevant priorities need to be identified before conducting studies. This can be achieved through assessing the concrete needs of the populations targeted (e.g., healthcare workers, families of victims, individuals suffering from isolation, disabilities, pre-existing physical and mental health issues, and the economically vulnerable) and subsequently conducting systematic reviews so as to avoid fragmentation and overlap. To this purpose, journals could require that some reports of primary research also include rapid reviews ( Tricco et al., 2015 ), a simplified form of systematic reviews. For instance, The Lancet journals require a “Research in context” box, which needs to be based on a systematic search. Study formats like Registered Reports, in which a study is accepted in principle after peer review of its rationale and methods ( Hardwicke and Ioannidis, 2018 ), are uniquely suited for this change. Third, methodological rigor and reproducibility in design, conduct, analysis, and reporting should move to the forefront of the human behavior research agenda ( Cristea and Naudet, 2019 ). For example, preregistration of studies ( Nosek et al., 2019 ) in a public repository should be widely employed to support transparent reporting. Registered reports ( Hardwicke and Ioannidis, 2018 ) and study protocols are formats that ensure rigorous evaluation of the experimental design and statistical analysis plan before commencing data collection, thus making sure shortcuts and methodological shortcomings are eliminated. Fourth, data and code sharing, along with the use of publicly available datasets (e.g., 1000 Functional Connectomes Project, Human Connectome Project), should become the norm. These practices allow the use of already-collected data to be maximized, including in terms of assessing reproducibility, conducting re-analyses using different methods, and exploring new hypotheses on large collections of data ( Cristea and Naudet, 2019 ). Fifth, to reduce publication bias, submission of all unpublished studies, the so-called “file drawer,” should be encouraged and supported. Reporting findings in preprints can aid this desideratum, but stronger incentives are necessary to ensure that preprints also transparently and completely report conducted research. The Preprint Review at eLife ( Elife, 2020 ), in which the journal effectively takes into review manuscripts posted on the preprint server BioRxiv, is a promising initiative in this direction. Journals could also create study formats specifically designed for publishing studies that resulted in inconclusive findings, even when caused by procedural issues, e.g., unclear manipulation checks, insufficient stimulus presentation times, or other technical errors. This would both aid transparency and help other researchers better prepare their own experiments. Sixth, peer review of both articles and preprints should be regarded as on par with the production of new research. Platforms like Publons help track reviewing activity, which could be rewarded by funders and academic institutions involved in hiring, promotion, or tenure ( Moher et al., 2018 ). Researchers who manage to publish less during the pandemic could still be compensated for the onerous activity of peer review, to the benefit of the entire community.

Of course, individual researchers cannot implement such sweeping changes on their own, without decisive action from policymakers like funding bodies, academic institutions, and journals. For instance, decisions related to hiring, promotion, or tenure of academics could reward several of the behaviors described, such as complete and transparent publication regardless of the results, availability of data and code, or contributions to peer review ( Moher et al., 2018 ). Academic institutions and funders should acknowledge the slowdown of experimental research during the pandemic and hence accelerate the move toward more “responsible indicators” that would incentivize best publication practices over productivity and citations ( Moher et al., 2018 ). Funders could encourage submissions leveraging existing datasets or developing tools for data re-use, e.g., to track multiple uses of the same dataset. Journals could stimulate data sharing by assigning priority to manuscripts sharing or re-using data and code, like re-analyses, or individual participant data meta-analyses.

Author Contributions

CG and IC contributed equally to this manuscript in terms of its conceivement and preparation. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was carried out within the scope of the project “use-inspired basic research”, for which the Department of General Psychology of the University of Padova has been recognized as “Dipartimento di eccellenza” by the Ministry of University and Research.

Abdolkhani, R., Gray, K., Borda, A., and Desouza, R. (2020). Quality assurance of health wearables data: participatory workshop on barriers, solutions, and expectations. JMIR mHealth uHealth 8:e15329. doi: 10.2196/15329

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Bromham, L., Dinnage, R., and Hua, X. (2016). Interdisciplinary research has consistently lower funding success. Nature 534, 684–687. doi: 10.1038/nature18315

Button, K. S., Ioannidis, J. P. A., Mokrysz, C., Nosek, B. A., Flint, J., Robinson, E. S. J., et al. (2013). Power failure: why small sample size undermines the reliability of neuroscience. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 14, 365–376. doi: 10.1038/nrn3475

Cristea, I. A., and Naudet, F. (2019). Increase value and reduce waste in research on psychological therapies. Behav. Res. Ther , 123:103479. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2019.103479

Crump, M. J. C., Mcdonnell, J. V., and Gureckis, T. M. (2013). Evaluating Amazon's mechanical turk as a tool for experimental behavioral research. PLoS ONE 8:e57410. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057410

Elife (2020). eLife Launches Service to Peer Review Preprints on bioRxiv . eLife. Available online at: https://elifesciences.org/for-the-press/a5a129f2/elife-launches-service-to-peer-review-preprints-on-biorxiv

Emanuel, E.J., Persad, G., Upshur, R., Thome, B., Parker, M., Glickman, A., et al. (2020). Fair allocation of scarce medical resources in the time of Covid-19. N. Engl. J. Med . 382, 2049–2055. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb2005114

Falagas, M. E., Karamanidou, C., Kastoris, A. C., Karlis, G., and Rafailidis, P. I. (2010). Psychosocial factors and susceptibility to or outcome of acute respiratory tract infections. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 14, 141–148. Available online at: https://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/iuatld/ijtld/2010/00000014/00000002/art00004#

Google Scholar

Germine, L., Nakayama, K., Duchaine, B. C., Chabris, C. F., Chatterjee, G., and Wilmer, J. B. (2012). Is the Web as good as the lab? Comparable performance from web and lab in cognitive/perceptual experiments. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 19, 847–857. doi: 10.3758/s13423-012-0296-9

Hardwicke, T. E., and Ioannidis, J. P. A. (2018). Mapping the universe of registered reports. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2, 793–796. doi: 10.1038/s41562-018-0444-y

Javelot, H., Spadazzi, A., Weiner, L., Garcia, S., Gentili, C., Kosel, M., et al. (2014). Telemonitoring with respect to mood disorders and information and communication technologies: overview and presentation of the PSYCHE project. Biomed Res. Int. 2014:104658. doi: 10.1155/2014/104658

Kissler, S. M., Tedijanto, C., Goldstein, E., Grad, Y. H., and Lipsitch, M. (2020). Projecting the transmission dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 through the postpandemic period. Science 368, 860–868. doi: 10.1126/science.abb5793

Leung, K., Wu, J. T., Liu, D., and Leung, G. M. (2020). First-wave COVID-19 transmissibility and severity in China outside Hubei after control measures, and second-wave scenario planning: a modelling impact assessment. Lancet 395, 1382–1393. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30746-7

Moher, D., Naudet, F., Cristea, I.A., Miedema, F., Ioannidis, J.P.A., and Goodman, S.N. (2018). Assessing scientists for hiring, promotion, and tenure. PLoS Biol. 16:e2004089. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.2004089

Munafò, M.R., Nosek, B.A., Bishop, D.V.M., Button, K.S., Chambers, C.D., Percie Du Sert, N., et al. (2017). A manifesto for reproducible science. Nat. Hum. Behav. 1:0021. doi: 10.1038/s41562-016-0021

CrossRef Full Text

Nosek, B.A., Beck, E.D., Campbell, L., Flake, J.K., Hardwicke, T.E., Mellor, D.T., et al. (2019). Preregistration is hard, and worthwhile. Trends Cogn. Sci. 23, 815–818. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2019.07.009

Open Science Collaboration (2015). Estimating the reproducibility of psychological science. Science 349:aac4716. doi: 10.1126/science.aac4716

Pierce, M., Mcmanus, S., Jessop, C., John, A., Hotopf, M., Ford, T., et al. (2020). Says who? The significance of sampling in mental health surveys during COVID-19. Lancet Psychiatry 7, 567–568. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30237-6

Rosenthal, R. (1976). Experimenter Effects in Behavioral Research, Enlarged Edn . Oxford: Irvington.

Shiffman, S., Stone, A.A., and Hufford, M.R. (2008). Ecological momentary assessment. Ann. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 4, 1–32. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091415

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Tricco, A.C., Antony, J., Zarin, W., Strifler, L., Ghassemi, M., Ivory, J., et al. (2015). A scoping review of rapid review methods. BMC Med. 13:224. doi: 10.1186/s12916-015-0465-6

Keywords: open science, data sharing, social distancing, preprint, preregistration, coronavirus disease, neuroimaging, experimental psychology

Citation: Gentili C and Cristea IA (2020) Challenges and Opportunities for Human Behavior Research in the Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Pandemic. Front. Psychol. 11:1786. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01786

Received: 29 April 2020; Accepted: 29 June 2020; Published: 10 July 2020.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2020 Gentili and Cristea. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Claudio Gentili, c.gentili@unipd.it

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Happiness and Prosocial Behavior: An Evaluation of the Evidence

- Lara B. Aknin Associate Professor, Simon Fraser University

- Ashley V. Whillans Assistant Professor, Harvard Business School

- Michael I. Norton Professor, Harvard Business School

- Elizabeth W. Dunn Professor, University of British Columbia

Introduction

How to interpret the evidence, well-being benefits of giving time, well-being benefits of giving money, different currencies, different contexts, when giving to others is most likely to increase well-being, how to encourage prosociality.

Humans are an extremely prosocial species. Compared to most primates, humans provide more assistance to family, friends, and strangers, even when costly. [1] Why do people devote their resources to helping others? In this chapter, we examine whether engaging in two specific types of prosocial behavior, mainly donating one’s time and money to others, promotes subjective well-being, which encompasses greater positive affect, lower negative affect, and greater life satisfaction. [2] Next, we identify the conditions under which the well-being benefits of prosociality are most likely to emerge. Finally, we briefly highlight several levers that can be used to increase prosocial behavior, thereby potentially increasing well-being.

In interpreting the evidence presented in this chapter, it is crucial to recognize that most research on generosity and happiness has substantial methodological limitations. Many of the studies we describe are correlational, and therefore causal conclusions cannot be drawn. For example, if people who give to charity report higher happiness than people who do not, it is tempting to conclude that giving to charity increases happiness. But it is also possible that happier people are more likely to give to charity (i.e. reverse causality ). Or, people who give to charity may be wealthier, and their wealth – not their charitable giving – may make them happy. Researchers typically try to deal with this problem by statistically controlling for “confounding variables,” such as wealth. This approach works reasonably well when the variable of interest (e.g., charitable giving) and any confounding variables (e.g., wealth) are measured with a high degree of precision.

In reality, however, it is often difficult to reliably measure complex constructs (like wealth) using brief, self-report surveys. Rather than reporting all of their assets and liabilities, survey respondents might be asked to report their household income, which provides a sensible—but incomplete—indicator of the broader construct of wealth. For example, if Sian and Kelly each earn $60,000/year, but Sian has six kids and no savings, and Kelly has no kids and a six-figure savings account, then Kelly is wealthier than Sian and may be able to give more money to charity. Now, let’s imagine the relationship between charitable giving and happiness was really explained entirely by wealth. Because income does not fully capture the complex concept of wealth, charitable giving might still predict happiness over and above income because the ability to give captures an aspect of financial security not captured by income. Although researchers have recognized these challenges for decades, recent work using computer simulations has demonstrated that effectively ruling out confounds is harder than many scholars have assumed. [3]

To overcome this issue, it is essential to conduct experiments in which the variable of interest can be manipulated without altering other variables. For example, using experimental methodology, researchers can give participants money and assign them at random to spend it on themselves or on others; because participants are assigned to engage in generous spending based on the flip of a coin (metaphorically speaking), they should not be any wealthier than those assigned to spend money on themselves, on average. While experiments may sometimes seem slight or artificial because they typically involve adjustments of small behaviours, this approach eliminates many pesky confounds, like wealth, that plague correlational research, thereby enabling statements about how generous behavior affects happiness.

As the example above illustrates, conducting experiments tends to be much costlier than simply asking survey questions. Therefore, researchers have traditionally relied on relatively small sample sizes when conducting experiments, particularly when the experiments attempt to alter people’s behavior in the real world. This reliance on small sample sizes not only creates a risk of failing to detect effects that are real—it also creates a high risk of finding “false positives,” effects that turn out not to be real. [4]

In order to establish replicable effects, researchers now recognize that it is important to conduct experiments with sufficiently large sample sizes. A recent meta-analysis concluded that experiments on helping and happiness should include at least 200 participants per condition. [5] This means that an experiment in which participants are randomly assigned to one of two conditions needs at least 400 participants in order to produce reliable results. Unfortunately, almost none of the experiments conducted in this area meet this criterion, although we specifically flag those that do. In fact, many studies in this area include fewer than 50 participants per condition (including some of our own). This is worrisome because samples sizes much under 50 are barely sufficient to detect that men weigh more than women (at least 46 men and 46 women are needed to reliably detect this difference, which is about half a standard deviation). [6] Thus, unless researchers are examining an effect that is genuinely large (i.e., bigger than the gender difference in weight), studies with group sizes under 50 run a high risk of being false positives. For this reason, we describe studies with group sizes below 50 as “small” throughout this chapter, and we urge readers to treat evidence from these studies as suggestive rather than conclusive.

Volunteering is defined as helping another person with no expectation of monetary compensation. [7] A great deal of correlational research shows that spending time helping others is associated with emotional benefits for the giver. Indeed, research has documented a robust link between volunteering and greater life satisfaction, positive affect, and reduced depression. In a review of 37 correlational studies with samples ranging from 15 to over 2,100, [8] adult volunteers scored significantly higher on quality of life measures compared to non-volunteers. [9]

The conclusions of this review paper have been confirmed in two more recent large-scale examinations. First, a recent synthesis of the literature including 17 longitudinal cohort studies (N=72,241) found that volunteering was linked to greater life satisfaction, greater quality of life, and lower rates of depression. [10] The majority of the studies included in this synthesis used inconsistent quality of life measures and participants were mostly women living in North America aged fifty or older. Fortunately, converging data from a large nationally representative sample of respondents living in the UK helps to overcome these limitations. In a sample of 66,343 respondents, volunteering was associated with greater well-being, as measured by the General Health Survey, a validated scale which includes several items related to general happiness. [11] In this study, the well-being benefits of volunteering emerged most strongly for individuals forty years of age or older. Collectively, these data provide compelling evidence that there is a reliable link between volunteering and various measures of subjective well-being, while also indicating the possibility of critical moderators, which is a point we return to below.

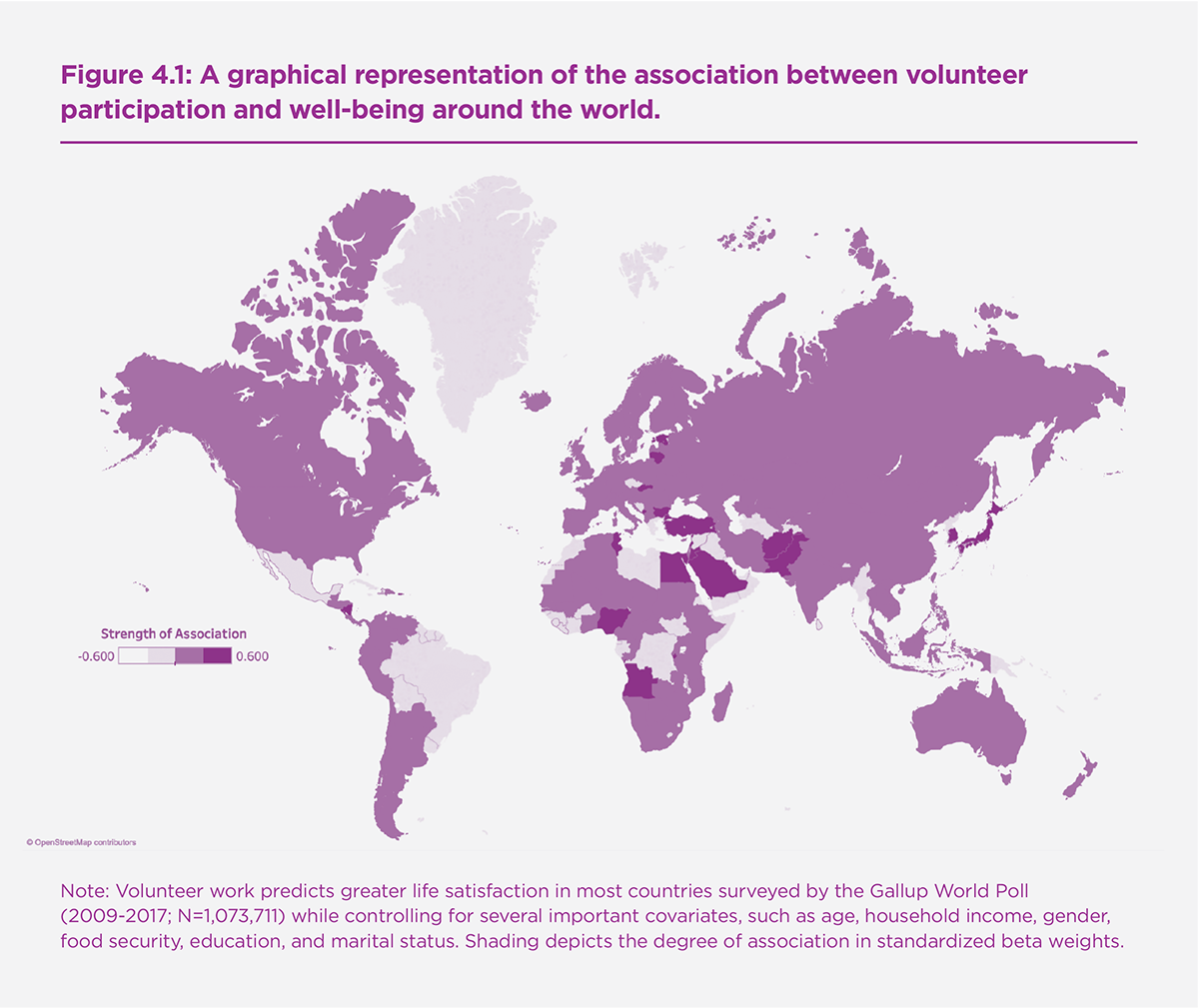

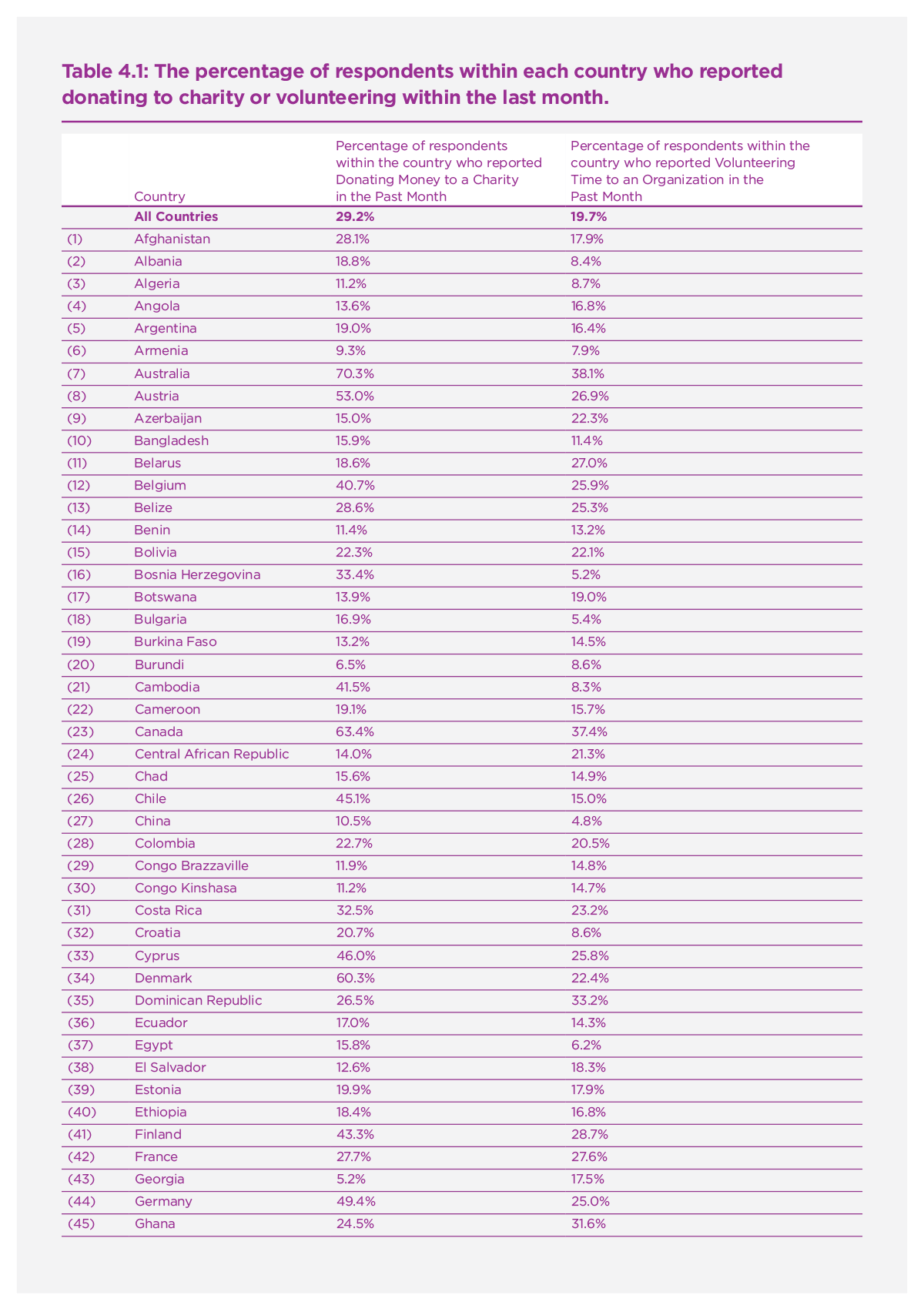

Additional research suggests that the relationship between volunteering and well-being appears to be a cross-cultural universal. Researchers analyzed data from the Gallup World Poll, a survey that comprises representative samples from over 130 countries. Across both poor and wealthy countries (N=1,073,711), there is a positive relationship between volunteer participation and well-being (see Table 4.1 for average monthly estimates of the percentage of people who volunteered time or made charitable donations in years 2009-2017 of the Gallup World Poll, and Figure 4.1 for a graphical representation of the individual-level data depicting the strength of the relationship between volunteering and well-being for the same years). [12] These results further point to the reliability of the association between volunteering and subjective well-being across diverse economic, political, and cultural settings. [13]

Of course, it is possible that demographic differences between volunteers and non-volunteers explain observed differences in well-being. [14] For example, women are more likely than men to volunteer [15] and derive greater satisfaction from communal activities. [16] Moreover, a large survey of over 2,000 people in the UK indicates volunteers are older and from higher socioeconomic backgrounds. [17] In addition, a large sample of over 5,000 responses to the English Longitudinal Study of Aging indicates that volunteers are healthier than non-volunteers. [18] It is also possible that the benefits of volunteering are driven entirely by the fact that people who volunteer are generally more socially connected than non-volunteers. [19] Stated differently, it is possible that there is no unique relationship between volunteering and well-being. Casting doubt on these possibilities, in a sample of 10,317 women and men recruited from the Wisconsin Longitudinal Study, volunteering predicted well-being above and beyond numerous demographic characteristics and participation in self-focused social activities, such as formal sports, cultural groups, or country clubs. [20] The results of these large-scale surveys suggest a robust link between volunteering and well-being that exists beyond demographics and social connectedness.

Despite the seemingly ubiquitous association between volunteering and well-being, there is very little experimental evidence showing that volunteering causally improves happiness. For instance, in a systematic review of nine experiments with a total sample of 715 participants (median number of participants per study = 54), researchers found no evidence that volunteering casually improved well-being or reduced depressive symptoms. [21] Consistent with this observation, in a more recent experimental study, 106 Canadian 10th graders were assigned to volunteer 1-2 hours per week for 10 consecutive weeks or to a wait-list control. [22] Students assigned to volunteer showed no change in positive affect, negative affect, or self-esteem as compared to the wait-list.

Similarly, the largest known experimental study in the literature to date showed no causal impact of volunteering on subjective well-being. A sample of 293 college students in Boston were randomly assigned to complete 10-12 hours of formal volunteering each week or were randomly assigned to a wait-list control group. When subjective well-being was assessed for both groups, there was no positive benefit of formal volunteering. [23] Unlike the majority of published experimental research in this area, this experiment was pre-registered and sufficiently powered to detect a small effect of volunteering on subjective well-being. Thus, this experimental study suggests that existing correlational data may have overestimated the well-being benefits of volunteering. [24]

Another possibility is that there are critical conditions predicting when and for whom volunteering promotes well-being. In a study of more than 1,000 community dwelling older adults living in the US, volunteering was linked to greater well-being for individuals who believe that other people are fundamentally good versus those higher in hostile cynicism and believe other people are selfish and greedy. [25] As described above, older individuals benefit more from formal volunteering. [26] Relatedly, individuals who score higher in depressive symptoms also report experiencing greater boosts in well-being from volunteering. In one daily diary study— which asked 100 participants to report on their mood and helping activities each day for ten days— respondents experiencing the greatest depressive symptoms reported the greatest mood benefits from helping others. [27] Individuals who score lower in agreeableness also experience greater well-being in response to volunteering. In one experimental study (N=348), participants who scored lower in agreeableness, and who were randomly assigned to spend time helping other people in their daily life (vs. a control condition), reported the greatest increases in life satisfaction over a three-week intervention study period. [28]

In summary, the research presented in this section provides evidence for a reliable association between formal volunteering and subjective well-being in large correlational surveys but reveals little evidence for a causal relationship. Given the dearth of large-scale experimental studies sufficiently powered to explore this question, more research is needed. Recent findings indicate that individuals from at-risk groups gain the greatest benefits from volunteering, suggesting that these may be the most fruitful samples for further exploration.

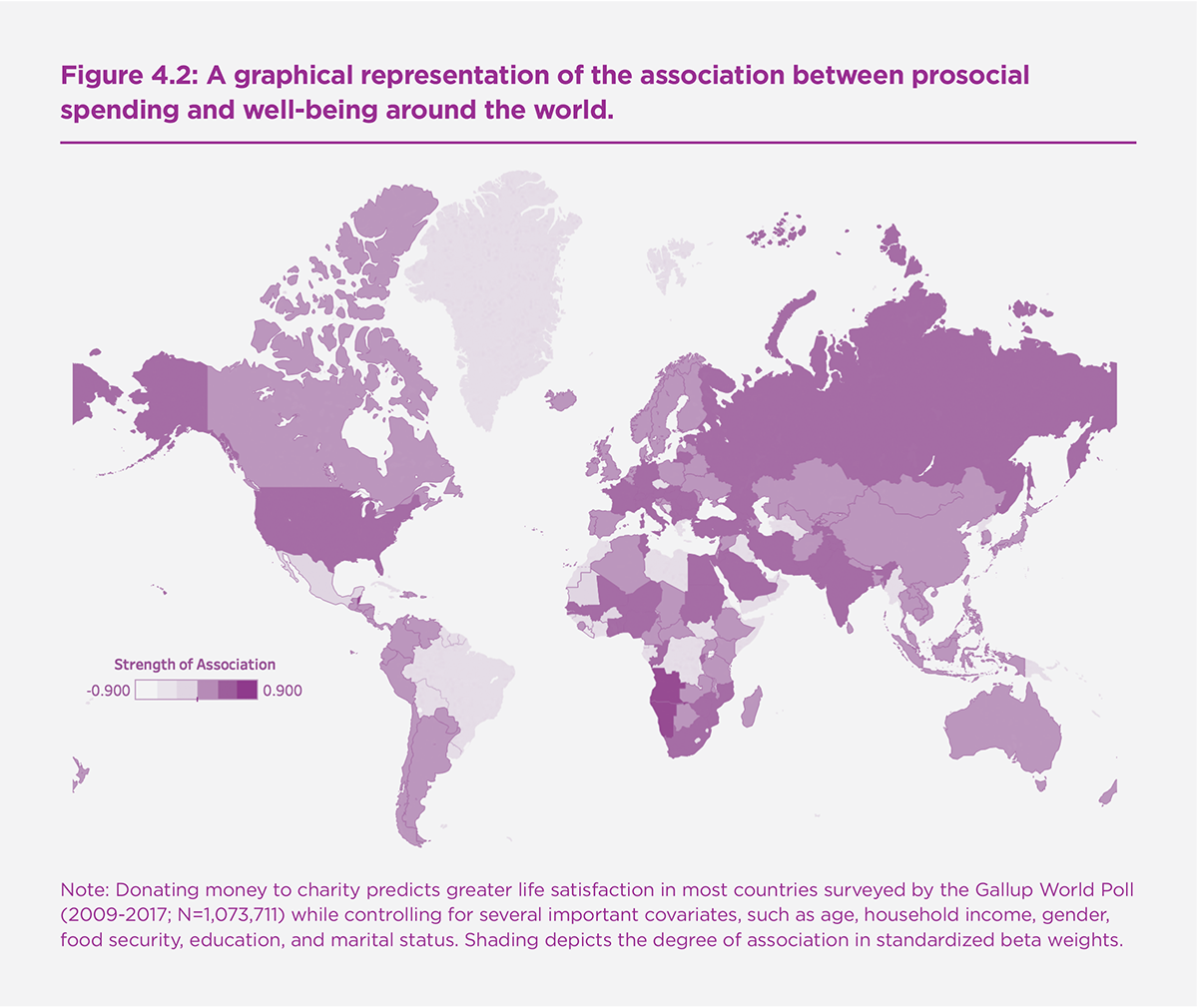

Spending money on others – often called prosocial spending – is associated with higher levels of well-being. Evidence for this relationship comes from various sources. For instance, individual who pay more money in taxes – thereby directing a portion of their income to fellow citizens through public goods – report greater well-being in over two decades of German panel data, even while controlling for income and a number of other predictors of happiness. [29] In addition, charitable donations appear to activate reward centers within the human brain, such as the orbital frontal cortex and ventral striatum. [30] Moreover, in a representative sample of over 600 American adults, individuals who spent more money in a typical month on others by providing gifts and donating to charity reported greater happiness. [31] Meanwhile, how much money people reported spending on themselves in a typical month was unrelated to their happiness. [32] More broadly, responses from more than one million people in 130 countries surveyed by the Gallup World Poll indicates that financial generosity – measured as whether one has donated to charity in the past month – is one of the top six predictors of life satisfaction around the world (see Table 2.1 in Chapter 2 for the latest aggregate results, while Figure 4.2 shows results based on individual data).

In contrast to the volunteering literature discussed above, the causal impact of financial generosity on happiness is supported by several small experimental studies. [33] For example, in one of the first experiments on this topic, 46 Canadian students were randomly assigned to spend a five or twenty dollar windfall on themselves or others by the end of the day. In the evening, all students were called on the phone to report their happiness levels. [34] Individuals randomly assigned to spend money on others (vs. themselves) reported significantly higher levels of happiness. Although the sample size of this initial study was very small and consisted only of university students, more recent research has provided further support for this idea. A large scale experiment using a similar design yields consistent findings with over 200 participants per condition. [35]

Several experiments support the possibility that the relationship between prosocial spending and happiness may be detectable in most humans around the globe. [36] For instance, participants in Canada (N=140), India (N=101), and Uganda (N=700) reported higher levels of happiness after reflecting on a time they spent money on others versus themselves. [37] The emotional benefits of generous spending are also detectable among individuals from rich and poor nations immediately after purchases are made. In one study, a total of 207 students from Canada and South Africa earned a small amount of money that they could use to purchase an edible treat, such as cookies or juice, available to them at a discounted price. Half the participants were told that the items they purchased were for themselves, and the other half of participants were told that the items they purchased would be donated to a sick child at a local hospital. Importantly, participants in both conditions were able to choose between whether they wanted to make a purchase (and, if so, what to buy) or take the cash for themselves. This choice provided participants with a sense of autonomy over their spending , which is important for experiencing the emotional rewards of giving (discussed in greater detail below). Immediately afterward, all participants reported their current positive affect. Converging with earlier findings, individuals who purchased items for others were happier. [38] Importantly, this finding emerged not only in Canada (where few students reported financial hardship), but also in South Africa, where more than 20% of respondents reported trouble securing food for their family in the past year.

Additional research suggests that the emotional benefits of prosocial spending are detectable even in places where people have had little to no contact with Western culture. Consider one study conducted with a small number of villagers (N=26) from a traditional society in Vanuatu, where villagers live in huts made from local materials, survive on subsistence farming, and have no running water or electricity. Villagers participated in a version of the goody-bag study, in which they earned a small sum of money that they could use to buy packaged candy, a rare treat on the island nation. Once again, half the participants were able to purchase the candy for themselves while the other half were able to purchase the candy for another villager. Consistent with previous research, villagers reported greater happiness after purchasing treats for others rather than themselves. [39]

As well as emerging around the world, the emotional rewards of giving may be detectable early in life. In one small study conducted with 20 Canadian toddlers, children were given eight edible treats and asked to share some of these treats with a puppet. Throughout the study, children’s’ facial responses were captured on film and later coded for happiness. Coders observed that toddlers showed larger smiles when giving treats away than when receiving treats themselves, [40] and this result has been replicated in a handful of subsequent studies with larger samples. [41]