- Privacy Policy

Home » Research Results Section – Writing Guide and Examples

Research Results Section – Writing Guide and Examples

Table of Contents

Research Results

Research results refer to the findings and conclusions derived from a systematic investigation or study conducted to answer a specific question or hypothesis. These results are typically presented in a written report or paper and can include various forms of data such as numerical data, qualitative data, statistics, charts, graphs, and visual aids.

Results Section in Research

The results section of the research paper presents the findings of the study. It is the part of the paper where the researcher reports the data collected during the study and analyzes it to draw conclusions.

In the results section, the researcher should describe the data that was collected, the statistical analysis performed, and the findings of the study. It is important to be objective and not interpret the data in this section. Instead, the researcher should report the data as accurately and objectively as possible.

Structure of Research Results Section

The structure of the research results section can vary depending on the type of research conducted, but in general, it should contain the following components:

- Introduction: The introduction should provide an overview of the study, its aims, and its research questions. It should also briefly explain the methodology used to conduct the study.

- Data presentation : This section presents the data collected during the study. It may include tables, graphs, or other visual aids to help readers better understand the data. The data presented should be organized in a logical and coherent way, with headings and subheadings used to help guide the reader.

- Data analysis: In this section, the data presented in the previous section are analyzed and interpreted. The statistical tests used to analyze the data should be clearly explained, and the results of the tests should be presented in a way that is easy to understand.

- Discussion of results : This section should provide an interpretation of the results of the study, including a discussion of any unexpected findings. The discussion should also address the study’s research questions and explain how the results contribute to the field of study.

- Limitations: This section should acknowledge any limitations of the study, such as sample size, data collection methods, or other factors that may have influenced the results.

- Conclusions: The conclusions should summarize the main findings of the study and provide a final interpretation of the results. The conclusions should also address the study’s research questions and explain how the results contribute to the field of study.

- Recommendations : This section may provide recommendations for future research based on the study’s findings. It may also suggest practical applications for the study’s results in real-world settings.

Outline of Research Results Section

The following is an outline of the key components typically included in the Results section:

I. Introduction

- A brief overview of the research objectives and hypotheses

- A statement of the research question

II. Descriptive statistics

- Summary statistics (e.g., mean, standard deviation) for each variable analyzed

- Frequencies and percentages for categorical variables

III. Inferential statistics

- Results of statistical analyses, including tests of hypotheses

- Tables or figures to display statistical results

IV. Effect sizes and confidence intervals

- Effect sizes (e.g., Cohen’s d, odds ratio) to quantify the strength of the relationship between variables

- Confidence intervals to estimate the range of plausible values for the effect size

V. Subgroup analyses

- Results of analyses that examined differences between subgroups (e.g., by gender, age, treatment group)

VI. Limitations and assumptions

- Discussion of any limitations of the study and potential sources of bias

- Assumptions made in the statistical analyses

VII. Conclusions

- A summary of the key findings and their implications

- A statement of whether the hypotheses were supported or not

- Suggestions for future research

Example of Research Results Section

An Example of a Research Results Section could be:

- This study sought to examine the relationship between sleep quality and academic performance in college students.

- Hypothesis : College students who report better sleep quality will have higher GPAs than those who report poor sleep quality.

- Methodology : Participants completed a survey about their sleep habits and academic performance.

II. Participants

- Participants were college students (N=200) from a mid-sized public university in the United States.

- The sample was evenly split by gender (50% female, 50% male) and predominantly white (85%).

- Participants were recruited through flyers and online advertisements.

III. Results

- Participants who reported better sleep quality had significantly higher GPAs (M=3.5, SD=0.5) than those who reported poor sleep quality (M=2.9, SD=0.6).

- See Table 1 for a summary of the results.

- Participants who reported consistent sleep schedules had higher GPAs than those with irregular sleep schedules.

IV. Discussion

- The results support the hypothesis that better sleep quality is associated with higher academic performance in college students.

- These findings have implications for college students, as prioritizing sleep could lead to better academic outcomes.

- Limitations of the study include self-reported data and the lack of control for other variables that could impact academic performance.

V. Conclusion

- College students who prioritize sleep may see a positive impact on their academic performance.

- These findings highlight the importance of sleep in academic success.

- Future research could explore interventions to improve sleep quality in college students.

Example of Research Results in Research Paper :

Our study aimed to compare the performance of three different machine learning algorithms (Random Forest, Support Vector Machine, and Neural Network) in predicting customer churn in a telecommunications company. We collected a dataset of 10,000 customer records, with 20 predictor variables and a binary churn outcome variable.

Our analysis revealed that all three algorithms performed well in predicting customer churn, with an overall accuracy of 85%. However, the Random Forest algorithm showed the highest accuracy (88%), followed by the Support Vector Machine (86%) and the Neural Network (84%).

Furthermore, we found that the most important predictor variables for customer churn were monthly charges, contract type, and tenure. Random Forest identified monthly charges as the most important variable, while Support Vector Machine and Neural Network identified contract type as the most important.

Overall, our results suggest that machine learning algorithms can be effective in predicting customer churn in a telecommunications company, and that Random Forest is the most accurate algorithm for this task.

Example 3 :

Title : The Impact of Social Media on Body Image and Self-Esteem

Abstract : This study aimed to investigate the relationship between social media use, body image, and self-esteem among young adults. A total of 200 participants were recruited from a university and completed self-report measures of social media use, body image satisfaction, and self-esteem.

Results: The results showed that social media use was significantly associated with body image dissatisfaction and lower self-esteem. Specifically, participants who reported spending more time on social media platforms had lower levels of body image satisfaction and self-esteem compared to those who reported less social media use. Moreover, the study found that comparing oneself to others on social media was a significant predictor of body image dissatisfaction and lower self-esteem.

Conclusion : These results suggest that social media use can have negative effects on body image satisfaction and self-esteem among young adults. It is important for individuals to be mindful of their social media use and to recognize the potential negative impact it can have on their mental health. Furthermore, interventions aimed at promoting positive body image and self-esteem should take into account the role of social media in shaping these attitudes and behaviors.

Importance of Research Results

Research results are important for several reasons, including:

- Advancing knowledge: Research results can contribute to the advancement of knowledge in a particular field, whether it be in science, technology, medicine, social sciences, or humanities.

- Developing theories: Research results can help to develop or modify existing theories and create new ones.

- Improving practices: Research results can inform and improve practices in various fields, such as education, healthcare, business, and public policy.

- Identifying problems and solutions: Research results can identify problems and provide solutions to complex issues in society, including issues related to health, environment, social justice, and economics.

- Validating claims : Research results can validate or refute claims made by individuals or groups in society, such as politicians, corporations, or activists.

- Providing evidence: Research results can provide evidence to support decision-making, policy-making, and resource allocation in various fields.

How to Write Results in A Research Paper

Here are some general guidelines on how to write results in a research paper:

- Organize the results section: Start by organizing the results section in a logical and coherent manner. Divide the section into subsections if necessary, based on the research questions or hypotheses.

- Present the findings: Present the findings in a clear and concise manner. Use tables, graphs, and figures to illustrate the data and make the presentation more engaging.

- Describe the data: Describe the data in detail, including the sample size, response rate, and any missing data. Provide relevant descriptive statistics such as means, standard deviations, and ranges.

- Interpret the findings: Interpret the findings in light of the research questions or hypotheses. Discuss the implications of the findings and the extent to which they support or contradict existing theories or previous research.

- Discuss the limitations : Discuss the limitations of the study, including any potential sources of bias or confounding factors that may have affected the results.

- Compare the results : Compare the results with those of previous studies or theoretical predictions. Discuss any similarities, differences, or inconsistencies.

- Avoid redundancy: Avoid repeating information that has already been presented in the introduction or methods sections. Instead, focus on presenting new and relevant information.

- Be objective: Be objective in presenting the results, avoiding any personal biases or interpretations.

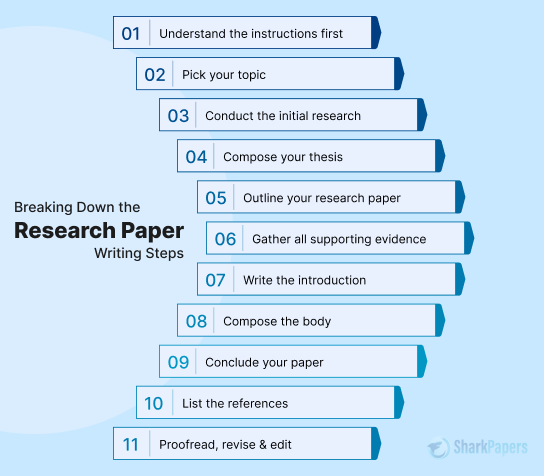

When to Write Research Results

Here are situations When to Write Research Results”

- After conducting research on the chosen topic and obtaining relevant data, organize the findings in a structured format that accurately represents the information gathered.

- Once the data has been analyzed and interpreted, and conclusions have been drawn, begin the writing process.

- Before starting to write, ensure that the research results adhere to the guidelines and requirements of the intended audience, such as a scientific journal or academic conference.

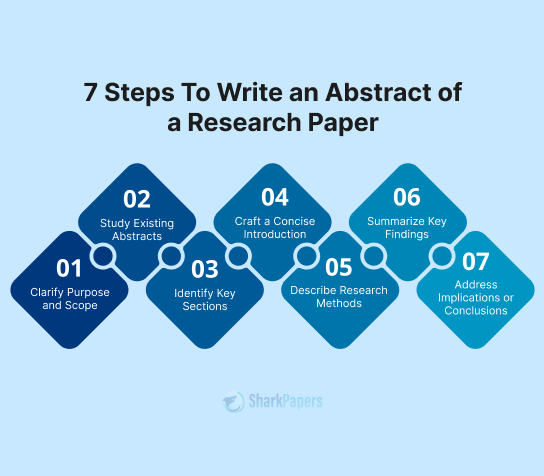

- Begin by writing an abstract that briefly summarizes the research question, methodology, findings, and conclusions.

- Follow the abstract with an introduction that provides context for the research, explains its significance, and outlines the research question and objectives.

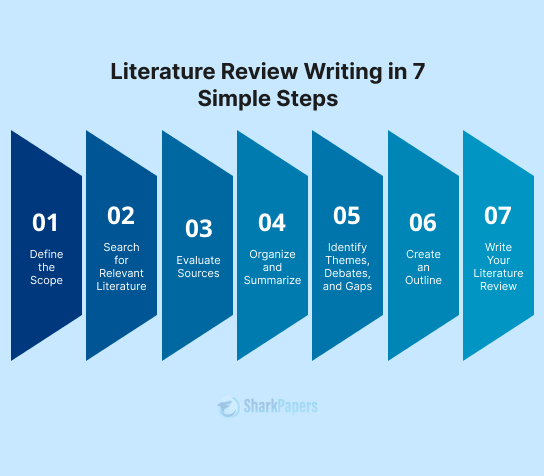

- The next section should be a literature review that provides an overview of existing research on the topic and highlights the gaps in knowledge that the current research seeks to address.

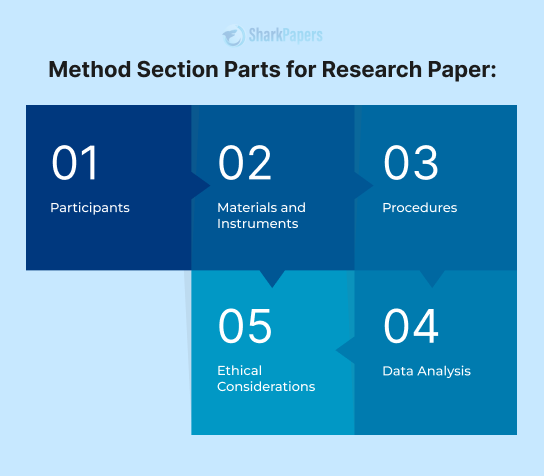

- The methodology section should provide a detailed explanation of the research design, including the sample size, data collection methods, and analytical techniques used.

- Present the research results in a clear and concise manner, using graphs, tables, and figures to illustrate the findings.

- Discuss the implications of the research results, including how they contribute to the existing body of knowledge on the topic and what further research is needed.

- Conclude the paper by summarizing the main findings, reiterating the significance of the research, and offering suggestions for future research.

Purpose of Research Results

The purposes of Research Results are as follows:

- Informing policy and practice: Research results can provide evidence-based information to inform policy decisions, such as in the fields of healthcare, education, and environmental regulation. They can also inform best practices in fields such as business, engineering, and social work.

- Addressing societal problems : Research results can be used to help address societal problems, such as reducing poverty, improving public health, and promoting social justice.

- Generating economic benefits : Research results can lead to the development of new products, services, and technologies that can create economic value and improve quality of life.

- Supporting academic and professional development : Research results can be used to support academic and professional development by providing opportunities for students, researchers, and practitioners to learn about new findings and methodologies in their field.

- Enhancing public understanding: Research results can help to educate the public about important issues and promote scientific literacy, leading to more informed decision-making and better public policy.

- Evaluating interventions: Research results can be used to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions, such as treatments, educational programs, and social policies. This can help to identify areas where improvements are needed and guide future interventions.

- Contributing to scientific progress: Research results can contribute to the advancement of science by providing new insights and discoveries that can lead to new theories, methods, and techniques.

- Informing decision-making : Research results can provide decision-makers with the information they need to make informed decisions. This can include decision-making at the individual, organizational, or governmental levels.

- Fostering collaboration : Research results can facilitate collaboration between researchers and practitioners, leading to new partnerships, interdisciplinary approaches, and innovative solutions to complex problems.

Advantages of Research Results

Some Advantages of Research Results are as follows:

- Improved decision-making: Research results can help inform decision-making in various fields, including medicine, business, and government. For example, research on the effectiveness of different treatments for a particular disease can help doctors make informed decisions about the best course of treatment for their patients.

- Innovation : Research results can lead to the development of new technologies, products, and services. For example, research on renewable energy sources can lead to the development of new and more efficient ways to harness renewable energy.

- Economic benefits: Research results can stimulate economic growth by providing new opportunities for businesses and entrepreneurs. For example, research on new materials or manufacturing techniques can lead to the development of new products and processes that can create new jobs and boost economic activity.

- Improved quality of life: Research results can contribute to improving the quality of life for individuals and society as a whole. For example, research on the causes of a particular disease can lead to the development of new treatments and cures, improving the health and well-being of millions of people.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Critical Analysis – Types, Examples and Writing...

Dissertation vs Thesis – Key Differences

Research Findings – Types Examples and Writing...

Institutional Review Board – Application Sample...

Survey Instruments – List and Their Uses

Future Research – Thesis Guide

- Research Process

- Manuscript Preparation

- Manuscript Review

- Publication Process

- Publication Recognition

- Language Editing Services

- Translation Services

How to Write the Results Section: Guide to Structure and Key Points

- 4 minute read

- 83.2K views

Table of Contents

The ‘ Results’ section of a research paper, like the ‘Introduction’ and other key parts, attracts significant attention from editors, reviewers, and readers. The reason lies in its critical role — that of revealing the key findings of a study and demonstrating how your research fills a knowledge gap in your field of study. Given its importance, crafting a clear and logically structured results section is essential.

In this article, we will discuss the key elements of an effective results section and share strategies for making it concise and engaging. We hope this guide will help you quickly grasp ways of writing the results section, avoid common pitfalls, and make your writing process more efficient and effective.

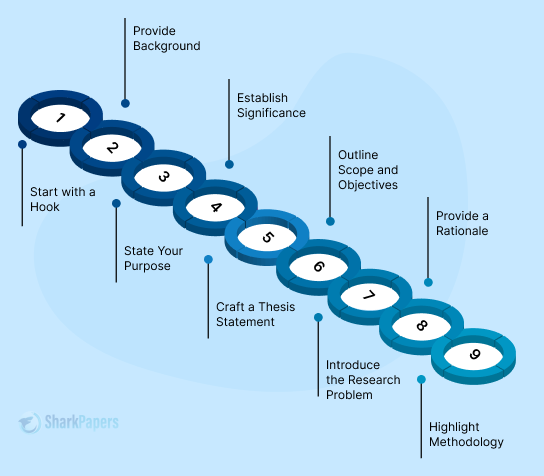

Structure of the results section

Briefly restate the research topic in the introduction : Although the main purpose of the results section in a research paper is to list the notable findings of a study, it is customary to start with a brief repetition of the research question. This helps refocus the reader, allowing them to better appreciate the relevance of the findings. Additionally, restating the research question establishes a connection to the previous section of the paper, creating a smoother flow of information.

Systematically present your research findings : Address the primary research question first, followed by the secondary research questions. If your research addresses multiple questions, mention the findings related to each one individually to ensure clarity and coherence.

Represent your results visually: Graphs, tables, and other figures can help illustrate the findings of your paper, especially if there is a large amount of data in the results. As a rule of thumb, use a visual medium like a graph or a table if you wish to present three or more statistical values simultaneously.

Graphical or tabular representations of data can also make your results section more visually appealing. Remember, an appealing and well-organized results section can help peer reviewers better understand the merits of your research, thereby increasing your chances of publication.

Practical guidance for writing an effective ‘Results’ section

- Always use simple and plain language. Avoid the use of uncertain or unclear expressions.

- The findings of the study must be expressed in an objective and unbiased manner. While it is acceptable to correlate certain findings , it is best to avoid over-interpreting the results. In addition, avoid using subjective or emotional words , such as “interestingly” or “unfortunately”, to describe the results as this may cause readers to doubt the objectivity of the paper.

- The content balances simplicity with comprehensiveness . For statistical data, simply describe the relevant tests and explain their results without mentioning raw data. If the study involves multiple hypotheses, describe the results for each one separately to avoid confusion and aid understanding. To enhance credibility, e nsure that negative results , if any, are included in this section, even if they do not support the research hypothesis.

- Wherever possible, use illustrations like tables, figures, charts, or other visual representations to highlight the results of your research paper. Mention these illustrations in the text, but do not repeat the information that they convey ¹ .

Difference between data, results, and discussion sections

Data , results, and discussion sections all communicate the findings of a study, but each serves a distinct purpose with varying levels of interpretation.

In the results section , one cannot provide data without interpreting its relevance or make statements without citing data ² . In a sense, the results section does not draw connections between different data points. Therefore, there is a certain level of interpretation involved in drawing results out of data.

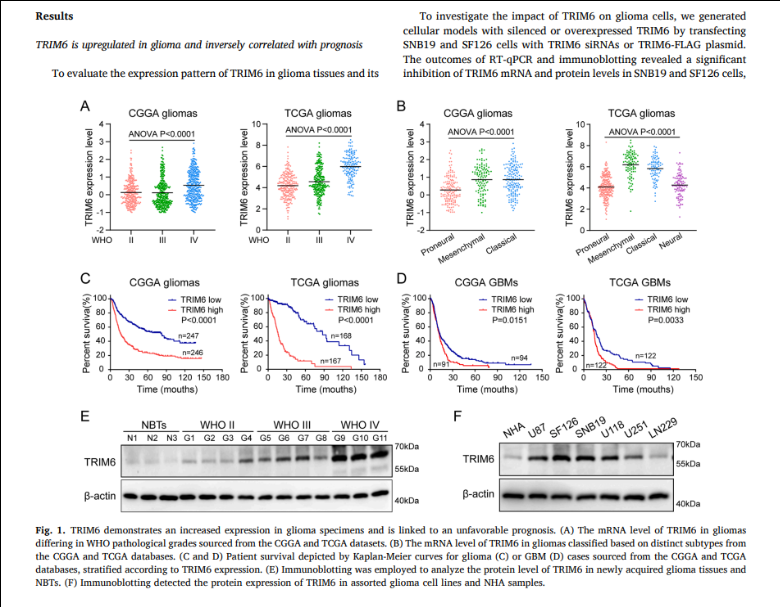

(The example is intended to showcase how the visual elements and text in the results section complement each other ³ . The academic viewpoints included in the illustrative screenshots should not be used as references.)

The discussion section allows authors even more interpretive freedom compared to the results section. Here, data and patterns within the data are compared with the findings from other studies to make more generalized points. Unlike the results section , which focuses purely on factual data, the discussion section touches upon hypothetical information, drawing conjectures and suggesting future directions for research.

The ‘ Results’ section serves as the core of a research paper, capturing readers’ attention and providing insights into the study’s essence. Regardless of the subject of your research paper, a well-written results section can generate interest in your research. By following the tips outlined here, you can create a results section that effectively communicates your finding and invites further exploration. Remember, clarity is the key, and with the right approach, your results section can guide readers through the intricacies of your research.

Professionals at Elsevier Language Services know the secret to writing a well-balanced results section. With their expert suggestions, you can ensure that your findings come across clearly to the reader. To maximize your chances of publication, reach out to Elsevier Language Services today !

Type in wordcount for Standard Total: USD EUR JPY Follow this link if your manuscript is longer than 12,000 words. Upload

Reference

- Cetin, S., & Hackam, D. J. (2005). An approach to the writing of a scientific manuscript. Journal of Surgical Research, 128(2), 165–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2005.07.002

- Bahadoran, Z., Mirmiran, P., Zadeh-Vakili, A., Hosseinpanah, F., & Ghasemi, A. (2019). The Principles of Biomedical Scientific Writing: Results. International Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism/International Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism., In Press (In Press). https://doi.org/10.5812/ijem.92113

- Guo, J., Wang, J., Zhang, P., Wen, P., Zhang, S., Dong, X., & Dong, J. (2024). TRIM6 promotes glioma malignant progression by enhancing FOXO3A ubiquitination and degradation. Translational Oncology, 46, 101999. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranon.2024.101999

Writing a good review article

Why is data validation important in research?

You may also like.

Submission 101: What format should be used for academic papers?

Page-Turner Articles are More Than Just Good Arguments: Be Mindful of Tone and Structure!

A Must-see for Researchers! How to Ensure Inclusivity in Your Scientific Writing

Make Hook, Line, and Sinker: The Art of Crafting Engaging Introductions

Can Describing Study Limitations Improve the Quality of Your Paper?

A Guide to Crafting Shorter, Impactful Sentences in Academic Writing

6 Steps to Write an Excellent Discussion in Your Manuscript

How to Write Clear and Crisp Civil Engineering Papers? Here are 5 Key Tips to Consider

Input your search keywords and press Enter.

- Affiliate Program

- UNITED STATES

- 台灣 (TAIWAN)

- TÜRKIYE (TURKEY)

- Academic Editing Services

- - Research Paper

- - Journal Manuscript

- - Dissertation

- - College & University Assignments

- Admissions Editing Services

- - Application Essay

- - Personal Statement

- - Recommendation Letter

- - Cover Letter

- - CV/Resume

- Business Editing Services

- - Business Documents

- - Report & Brochure

- - Website & Blog

- Writer Editing Services

- - Script & Screenplay

- Our Editors

- Client Reviews

- Editing & Proofreading Prices

- Wordvice Points

- Partner Discount

- Plagiarism Checker

- APA Citation Generator

- MLA Citation Generator

- Chicago Citation Generator

- Vancouver Citation Generator

- - APA Style

- - MLA Style

- - Chicago Style

- - Vancouver Style

- Writing & Editing Guide

- Academic Resources

- Admissions Resources

How to Write the Results/Findings Section in Research

What is the research paper Results section and what does it do?

The Results section of a scientific research paper represents the core findings of a study derived from the methods applied to gather and analyze information. It presents these findings in a logical sequence without bias or interpretation from the author, setting up the reader for later interpretation and evaluation in the Discussion section. A major purpose of the Results section is to break down the data into sentences that show its significance to the research question(s).

The Results section appears third in the section sequence in most scientific papers. It follows the presentation of the Methods and Materials and is presented before the Discussion section —although the Results and Discussion are presented together in many journals. This section answers the basic question “What did you find in your research?”

What is included in the Results section?

The Results section should include the findings of your study and ONLY the findings of your study. The findings include:

- Data presented in tables, charts, graphs, and other figures (may be placed into the text or on separate pages at the end of the manuscript)

- A contextual analysis of this data explaining its meaning in sentence form

- All data that corresponds to the central research question(s)

- All secondary findings (secondary outcomes, subgroup analyses, etc.)

If the scope of the study is broad, or if you studied a variety of variables, or if the methodology used yields a wide range of different results, the author should present only those results that are most relevant to the research question stated in the Introduction section .

As a general rule, any information that does not present the direct findings or outcome of the study should be left out of this section. Unless the journal requests that authors combine the Results and Discussion sections, explanations and interpretations should be omitted from the Results.

How are the results organized?

The best way to organize your Results section is “logically.” One logical and clear method of organizing research results is to provide them alongside the research questions—within each research question, present the type of data that addresses that research question.

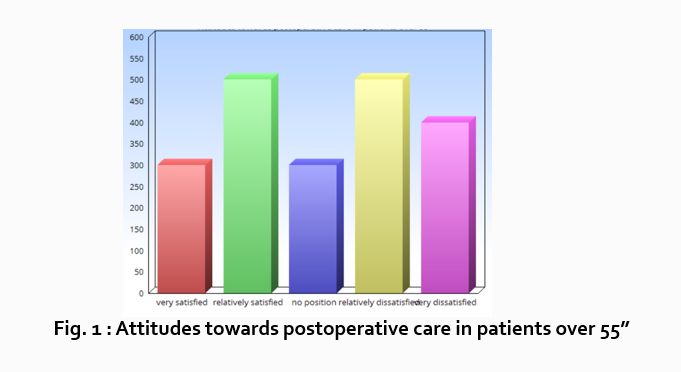

Let’s look at an example. Your research question is based on a survey among patients who were treated at a hospital and received postoperative care. Let’s say your first research question is:

“What do hospital patients over age 55 think about postoperative care?”

This can actually be represented as a heading within your Results section, though it might be presented as a statement rather than a question:

Attitudes towards postoperative care in patients over the age of 55

Now present the results that address this specific research question first. In this case, perhaps a table illustrating data from a survey. Likert items can be included in this example. Tables can also present standard deviations, probabilities, correlation matrices, etc.

Following this, present a content analysis, in words, of one end of the spectrum of the survey or data table. In our example case, start with the POSITIVE survey responses regarding postoperative care, using descriptive phrases. For example:

“Sixty-five percent of patients over 55 responded positively to the question “ Are you satisfied with your hospital’s postoperative care ?” (Fig. 2)

Include other results such as subcategory analyses. The amount of textual description used will depend on how much interpretation of tables and figures is necessary and how many examples the reader needs in order to understand the significance of your research findings.

Next, present a content analysis of another part of the spectrum of the same research question, perhaps the NEGATIVE or NEUTRAL responses to the survey. For instance:

“As Figure 1 shows, 15 out of 60 patients in Group A responded negatively to Question 2.”

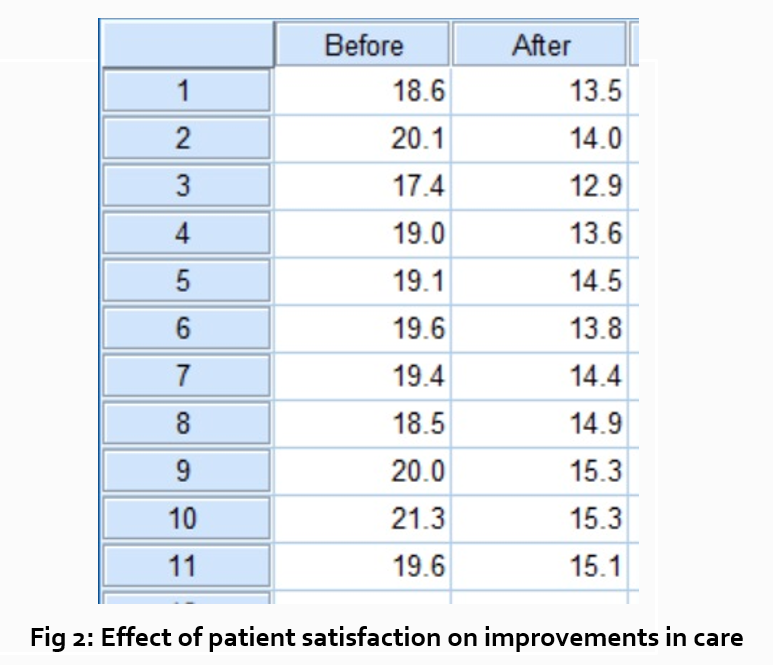

After you have assessed the data in one figure and explained it sufficiently, move on to your next research question. For example:

“How does patient satisfaction correspond to in-hospital improvements made to postoperative care?”

This kind of data may be presented through a figure or set of figures (for instance, a paired T-test table).

Explain the data you present, here in a table, with a concise content analysis:

“The p-value for the comparison between the before and after groups of patients was .03% (Fig. 2), indicating that the greater the dissatisfaction among patients, the more frequent the improvements that were made to postoperative care.”

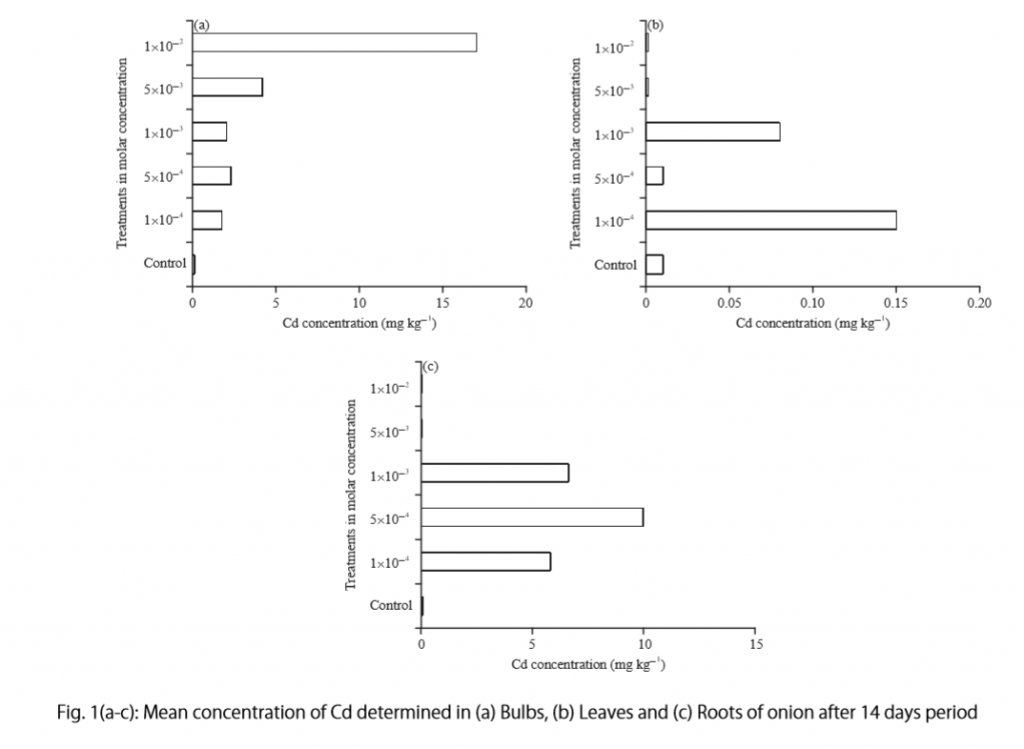

Let’s examine another example of a Results section from a study on plant tolerance to heavy metal stress . In the Introduction section, the aims of the study are presented as “determining the physiological and morphological responses of Allium cepa L. towards increased cadmium toxicity” and “evaluating its potential to accumulate the metal and its associated environmental consequences.” The Results section presents data showing how these aims are achieved in tables alongside a content analysis, beginning with an overview of the findings:

“Cadmium caused inhibition of root and leave elongation, with increasing effects at higher exposure doses (Fig. 1a-c).”

The figure containing this data is cited in parentheses. Note that this author has combined three graphs into one single figure. Separating the data into separate graphs focusing on specific aspects makes it easier for the reader to assess the findings, and consolidating this information into one figure saves space and makes it easy to locate the most relevant results.

Following this overall summary, the relevant data in the tables is broken down into greater detail in text form in the Results section.

- “Results on the bio-accumulation of cadmium were found to be the highest (17.5 mg kgG1) in the bulb, when the concentration of cadmium in the solution was 1×10G2 M and lowest (0.11 mg kgG1) in the leaves when the concentration was 1×10G3 M.”

Captioning and Referencing Tables and Figures

Tables and figures are central components of your Results section and you need to carefully think about the most effective way to use graphs and tables to present your findings . Therefore, it is crucial to know how to write strong figure captions and to refer to them within the text of the Results section.

The most important advice one can give here as well as throughout the paper is to check the requirements and standards of the journal to which you are submitting your work. Every journal has its own design and layout standards, which you can find in the author instructions on the target journal’s website. Perusing a journal’s published articles will also give you an idea of the proper number, size, and complexity of your figures.

Regardless of which format you use, the figures should be placed in the order they are referenced in the Results section and be as clear and easy to understand as possible. If there are multiple variables being considered (within one or more research questions), it can be a good idea to split these up into separate figures. Subsequently, these can be referenced and analyzed under separate headings and paragraphs in the text.

To create a caption, consider the research question being asked and change it into a phrase. For instance, if one question is “Which color did participants choose?”, the caption might be “Color choice by participant group.” Or in our last research paper example, where the question was “What is the concentration of cadmium in different parts of the onion after 14 days?” the caption reads:

“Fig. 1(a-c): Mean concentration of Cd determined in (a) bulbs, (b) leaves, and (c) roots of onions after a 14-day period.”

Steps for Composing the Results Section

Because each study is unique, there is no one-size-fits-all approach when it comes to designing a strategy for structuring and writing the section of a research paper where findings are presented. The content and layout of this section will be determined by the specific area of research, the design of the study and its particular methodologies, and the guidelines of the target journal and its editors. However, the following steps can be used to compose the results of most scientific research studies and are essential for researchers who are new to preparing a manuscript for publication or who need a reminder of how to construct the Results section.

Step 1 : Consult the guidelines or instructions that the target journal or publisher provides authors and read research papers it has published, especially those with similar topics, methods, or results to your study.

- The guidelines will generally outline specific requirements for the results or findings section, and the published articles will provide sound examples of successful approaches.

- Note length limitations on restrictions on content. For instance, while many journals require the Results and Discussion sections to be separate, others do not—qualitative research papers often include results and interpretations in the same section (“Results and Discussion”).

- Reading the aims and scope in the journal’s “ guide for authors ” section and understanding the interests of its readers will be invaluable in preparing to write the Results section.

Step 2 : Consider your research results in relation to the journal’s requirements and catalogue your results.

- Focus on experimental results and other findings that are especially relevant to your research questions and objectives and include them even if they are unexpected or do not support your ideas and hypotheses.

- Catalogue your findings—use subheadings to streamline and clarify your report. This will help you avoid excessive and peripheral details as you write and also help your reader understand and remember your findings. Create appendices that might interest specialists but prove too long or distracting for other readers.

- Decide how you will structure of your results. You might match the order of the research questions and hypotheses to your results, or you could arrange them according to the order presented in the Methods section. A chronological order or even a hierarchy of importance or meaningful grouping of main themes or categories might prove effective. Consider your audience, evidence, and most importantly, the objectives of your research when choosing a structure for presenting your findings.

Step 3 : Design figures and tables to present and illustrate your data.

- Tables and figures should be numbered according to the order in which they are mentioned in the main text of the paper.

- Information in figures should be relatively self-explanatory (with the aid of captions), and their design should include all definitions and other information necessary for readers to understand the findings without reading all of the text.

- Use tables and figures as a focal point to tell a clear and informative story about your research and avoid repeating information. But remember that while figures clarify and enhance the text, they cannot replace it.

Step 4 : Draft your Results section using the findings and figures you have organized.

- The goal is to communicate this complex information as clearly and precisely as possible; precise and compact phrases and sentences are most effective.

- In the opening paragraph of this section, restate your research questions or aims to focus the reader’s attention to what the results are trying to show. It is also a good idea to summarize key findings at the end of this section to create a logical transition to the interpretation and discussion that follows.

- Try to write in the past tense and the active voice to relay the findings since the research has already been done and the agent is usually clear. This will ensure that your explanations are also clear and logical.

- Make sure that any specialized terminology or abbreviation you have used here has been defined and clarified in the Introduction section .

Step 5 : Review your draft; edit and revise until it reports results exactly as you would like to have them reported to your readers.

- Double-check the accuracy and consistency of all the data, as well as all of the visual elements included.

- Read your draft aloud to catch language errors (grammar, spelling, and mechanics), awkward phrases, and missing transitions.

- Ensure that your results are presented in the best order to focus on objectives and prepare readers for interpretations, valuations, and recommendations in the Discussion section . Look back over the paper’s Introduction and background while anticipating the Discussion and Conclusion sections to ensure that the presentation of your results is consistent and effective.

- Consider seeking additional guidance on your paper. Find additional readers to look over your Results section and see if it can be improved in any way. Peers, professors, or qualified experts can provide valuable insights.

One excellent option is to use a professional English proofreading and editing service such as Wordvice, including our paper editing service . With hundreds of qualified editors from dozens of scientific fields, Wordvice has helped thousands of authors revise their manuscripts and get accepted into their target journals. Read more about the proofreading and editing process before proceeding with getting academic editing services and manuscript editing services for your manuscript.

As the representation of your study’s data output, the Results section presents the core information in your research paper. By writing with clarity and conciseness and by highlighting and explaining the crucial findings of their study, authors increase the impact and effectiveness of their research manuscripts.

For more articles and videos on writing your research manuscript, visit Wordvice’s Resources page.

Wordvice Resources

- How to Write a Research Paper Introduction

- Which Verb Tenses to Use in a Research Paper

- How to Write an Abstract for a Research Paper

- How to Write a Research Paper Title

- Useful Phrases for Academic Writing

- Common Transition Terms in Academic Papers

- Active and Passive Voice in Research Papers

- 100+ Verbs That Will Make Your Research Writing Amazing

- Tips for Paraphrasing in Research Papers

Generate accurate APA citations for free

- Knowledge Base

- APA Style 7th edition

- How to write an APA results section

Reporting Research Results in APA Style | Tips & Examples

Published on December 21, 2020 by Pritha Bhandari . Revised on January 17, 2024.

The results section of a quantitative research paper is where you summarize your data and report the findings of any relevant statistical analyses.

The APA manual provides rigorous guidelines for what to report in quantitative research papers in the fields of psychology, education, and other social sciences.

Use these standards to answer your research questions and report your data analyses in a complete and transparent way.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

What goes in your results section, introduce your data, summarize your data, report statistical results, presenting numbers effectively, what doesn’t belong in your results section, frequently asked questions about results in apa.

In APA style, the results section includes preliminary information about the participants and data, descriptive and inferential statistics, and the results of any exploratory analyses.

Include these in your results section:

- Participant flow and recruitment period. Report the number of participants at every stage of the study, as well as the dates when recruitment took place.

- Missing data . Identify the proportion of data that wasn’t included in your final analysis and state the reasons.

- Any adverse events. Make sure to report any unexpected events or side effects (for clinical studies).

- Descriptive statistics . Summarize the primary and secondary outcomes of the study.

- Inferential statistics , including confidence intervals and effect sizes. Address the primary and secondary research questions by reporting the detailed results of your main analyses.

- Results of subgroup or exploratory analyses, if applicable. Place detailed results in supplementary materials.

Write up the results in the past tense because you’re describing the outcomes of a completed research study.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Before diving into your research findings, first describe the flow of participants at every stage of your study and whether any data were excluded from the final analysis.

Participant flow and recruitment period

It’s necessary to report any attrition, which is the decline in participants at every sequential stage of a study. That’s because an uneven number of participants across groups sometimes threatens internal validity and makes it difficult to compare groups. Be sure to also state all reasons for attrition.

If your study has multiple stages (e.g., pre-test, intervention, and post-test) and groups (e.g., experimental and control groups), a flow chart is the best way to report the number of participants in each group per stage and reasons for attrition.

Also report the dates for when you recruited participants or performed follow-up sessions.

Missing data

Another key issue is the completeness of your dataset. It’s necessary to report both the amount and reasons for data that was missing or excluded.

Data can become unusable due to equipment malfunctions, improper storage, unexpected events, participant ineligibility, and so on. For each case, state the reason why the data were unusable.

Some data points may be removed from the final analysis because they are outliers—but you must be able to justify how you decided what to exclude.

If you applied any techniques for overcoming or compensating for lost data, report those as well.

Adverse events

For clinical studies, report all events with serious consequences or any side effects that occured.

Descriptive statistics summarize your data for the reader. Present descriptive statistics for each primary, secondary, and subgroup analysis.

Don’t provide formulas or citations for commonly used statistics (e.g., standard deviation) – but do provide them for new or rare equations.

Descriptive statistics

The exact descriptive statistics that you report depends on the types of data in your study. Categorical variables can be reported using proportions, while quantitative data can be reported using means and standard deviations . For a large set of numbers, a table is the most effective presentation format.

Include sample sizes (overall and for each group) as well as appropriate measures of central tendency and variability for the outcomes in your results section. For every point estimate , add a clearly labelled measure of variability as well.

Be sure to note how you combined data to come up with variables of interest. For every variable of interest, explain how you operationalized it.

According to APA journal standards, it’s necessary to report all relevant hypothesis tests performed, estimates of effect sizes, and confidence intervals.

When reporting statistical results, you should first address primary research questions before moving onto secondary research questions and any exploratory or subgroup analyses.

Present the results of tests in the order that you performed them—report the outcomes of main tests before post-hoc tests, for example. Don’t leave out any relevant results, even if they don’t support your hypothesis.

Inferential statistics

For each statistical test performed, first restate the hypothesis , then state whether your hypothesis was supported and provide the outcomes that led you to that conclusion.

Report the following for each hypothesis test:

- the test statistic value,

- the degrees of freedom ,

- the exact p- value (unless it is less than 0.001),

- the magnitude and direction of the effect.

When reporting complex data analyses, such as factor analysis or multivariate analysis, present the models estimated in detail, and state the statistical software used. Make sure to report any violations of statistical assumptions or problems with estimation.

Effect sizes and confidence intervals

For each hypothesis test performed, you should present confidence intervals and estimates of effect sizes .

Confidence intervals are useful for showing the variability around point estimates. They should be included whenever you report population parameter estimates.

Effect sizes indicate how impactful the outcomes of a study are. But since they are estimates, it’s recommended that you also provide confidence intervals of effect sizes.

Subgroup or exploratory analyses

Briefly report the results of any other planned or exploratory analyses you performed. These may include subgroup analyses as well.

Subgroup analyses come with a high chance of false positive results, because performing a large number of comparison or correlation tests increases the chances of finding significant results.

If you find significant results in these analyses, make sure to appropriately report them as exploratory (rather than confirmatory) results to avoid overstating their importance.

While these analyses can be reported in less detail in the main text, you can provide the full analyses in supplementary materials.

Are your APA in-text citations flawless?

The AI-powered APA Citation Checker points out every error, tells you exactly what’s wrong, and explains how to fix it. Say goodbye to losing marks on your assignment!

Get started!

To effectively present numbers, use a mix of text, tables , and figures where appropriate:

- To present three or fewer numbers, try a sentence ,

- To present between 4 and 20 numbers, try a table ,

- To present more than 20 numbers, try a figure .

Since these are general guidelines, use your own judgment and feedback from others for effective presentation of numbers.

Tables and figures should be numbered and have titles, along with relevant notes. Make sure to present data only once throughout the paper and refer to any tables and figures in the text.

Formatting statistics and numbers

It’s important to follow capitalization , italicization, and abbreviation rules when referring to statistics in your paper. There are specific format guidelines for reporting statistics in APA , as well as general rules about writing numbers .

If you are unsure of how to present specific symbols, look up the detailed APA guidelines or other papers in your field.

It’s important to provide a complete picture of your data analyses and outcomes in a concise way. For that reason, raw data and any interpretations of your results are not included in the results section.

It’s rarely appropriate to include raw data in your results section. Instead, you should always save the raw data securely and make them available and accessible to any other researchers who request them.

Making scientific research available to others is a key part of academic integrity and open science.

Interpretation or discussion of results

This belongs in your discussion section. Your results section is where you objectively report all relevant findings and leave them open for interpretation by readers.

While you should state whether the findings of statistical tests lend support to your hypotheses, refrain from forming conclusions to your research questions in the results section.

Explanation of how statistics tests work

For the sake of concise writing, you can safely assume that readers of your paper have professional knowledge of how statistical inferences work.

In an APA results section , you should generally report the following:

- Participant flow and recruitment period.

- Missing data and any adverse events.

- Descriptive statistics about your samples.

- Inferential statistics , including confidence intervals and effect sizes.

- Results of any subgroup or exploratory analyses, if applicable.

According to the APA guidelines, you should report enough detail on inferential statistics so that your readers understand your analyses.

- the test statistic value

- the degrees of freedom

- the exact p value (unless it is less than 0.001)

- the magnitude and direction of the effect

You should also present confidence intervals and estimates of effect sizes where relevant.

In APA style, statistics can be presented in the main text or as tables or figures . To decide how to present numbers, you can follow APA guidelines:

- To present three or fewer numbers, try a sentence,

- To present between 4 and 20 numbers, try a table,

- To present more than 20 numbers, try a figure.

Results are usually written in the past tense , because they are describing the outcome of completed actions.

The results chapter or section simply and objectively reports what you found, without speculating on why you found these results. The discussion interprets the meaning of the results, puts them in context, and explains why they matter.

In qualitative research , results and discussion are sometimes combined. But in quantitative research , it’s considered important to separate the objective results from your interpretation of them.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Bhandari, P. (2024, January 17). Reporting Research Results in APA Style | Tips & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved October 11, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/apa-style/results-section/

Is this article helpful?

Pritha Bhandari

Other students also liked, how to write an apa methods section, how to format tables and figures in apa style, reporting statistics in apa style | guidelines & examples, scribbr apa citation checker.

An innovative new tool that checks your APA citations with AI software. Say goodbye to inaccurate citations!

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- 7. The Results

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

The results section is where you report the findings of your study based upon the methodology [or methodologies] you applied to gather information. The results section should state the findings of the research arranged in a logical sequence without bias or interpretation. A section describing results should be particularly detailed if your paper includes data generated from your own research.

Annesley, Thomas M. "Show Your Cards: The Results Section and the Poker Game." Clinical Chemistry 56 (July 2010): 1066-1070.

Importance of a Good Results Section

When formulating the results section, it's important to remember that the results of a study do not prove anything . Findings can only confirm or reject the hypothesis underpinning your study. However, the act of articulating the results helps you to understand the problem from within, to break it into pieces, and to view the research problem from various perspectives.

The page length of this section is set by the amount and types of data to be reported . Be concise. Use non-textual elements appropriately, such as figures and tables, to present findings more effectively. In deciding what data to describe in your results section, you must clearly distinguish information that would normally be included in a research paper from any raw data or other content that could be included as an appendix. In general, raw data that has not been summarized should not be included in the main text of your paper unless requested to do so by your professor.

Avoid providing data that is not critical to answering the research question . The background information you described in the introduction section should provide the reader with any additional context or explanation needed to understand the results. A good strategy is to always re-read the background section of your paper after you have written up your results to ensure that the reader has enough context to understand the results [and, later, how you interpreted the results in the discussion section of your paper that follows].

Bavdekar, Sandeep B. and Sneha Chandak. "Results: Unraveling the Findings." Journal of the Association of Physicians of India 63 (September 2015): 44-46; Brett, Paul. "A Genre Analysis of the Results Section of Sociology Articles." English for Specific Speakers 13 (1994): 47-59; Go to English for Specific Purposes on ScienceDirect;Burton, Neil et al. Doing Your Education Research Project . Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2008; Results. The Structure, Format, Content, and Style of a Journal-Style Scientific Paper. Department of Biology. Bates College; Kretchmer, Paul. Twelve Steps to Writing an Effective Results Section. San Francisco Edit; "Reporting Findings." In Making Sense of Social Research Malcolm Williams, editor. (London;: SAGE Publications, 2003) pp. 188-207.

Structure and Writing Style

I. Organization and Approach

For most research papers in the social and behavioral sciences, there are two possible ways of organizing the results . Both approaches are appropriate in how you report your findings, but use only one approach.

- Present a synopsis of the results followed by an explanation of key findings . This approach can be used to highlight important findings. For example, you may have noticed an unusual correlation between two variables during the analysis of your findings. It is appropriate to highlight this finding in the results section. However, speculating as to why this correlation exists and offering a hypothesis about what may be happening belongs in the discussion section of your paper.

- Present a result and then explain it, before presenting the next result then explaining it, and so on, then end with an overall synopsis . This is the preferred approach if you have multiple results of equal significance. It is more common in longer papers because it helps the reader to better understand each finding. In this model, it is helpful to provide a brief conclusion that ties each of the findings together and provides a narrative bridge to the discussion section of the your paper.

NOTE: Just as the literature review should be arranged under conceptual categories rather than systematically describing each source, you should also organize your findings under key themes related to addressing the research problem. This can be done under either format noted above [i.e., a thorough explanation of the key results or a sequential, thematic description and explanation of each finding].

II. Content

In general, the content of your results section should include the following:

- Introductory context for understanding the results by restating the research problem underpinning your study . This is useful in re-orientating the reader's focus back to the research problem after having read a review of the literature and your explanation of the methods used for gathering and analyzing information.

- Inclusion of non-textual elements, such as, figures, charts, photos, maps, tables, etc. to further illustrate key findings, if appropriate . Rather than relying entirely on descriptive text, consider how your findings can be presented visually. This is a helpful way of condensing a lot of data into one place that can then be referred to in the text. Consider referring to appendices if there is a lot of non-textual elements.

- A systematic description of your results, highlighting for the reader observations that are most relevant to the topic under investigation . Not all results that emerge from the methodology used to gather information may be related to answering the " So What? " question. Do not confuse observations with interpretations; observations in this context refers to highlighting important findings you discovered through a process of reviewing prior literature and gathering data.

- The page length of your results section is guided by the amount and types of data to be reported . However, focus on findings that are important and related to addressing the research problem. It is not uncommon to have unanticipated results that are not relevant to answering the research question. This is not to say that you don't acknowledge tangential findings and, in fact, can be referred to as areas for further research in the conclusion of your paper. However, spending time in the results section describing tangential findings clutters your overall results section and distracts the reader.

- A short paragraph that concludes the results section by synthesizing the key findings of the study . Highlight the most important findings you want readers to remember as they transition into the discussion section. This is particularly important if, for example, there are many results to report, the findings are complicated or unanticipated, or they are impactful or actionable in some way [i.e., able to be pursued in a feasible way applied to practice].

NOTE: Always use the past tense when referring to your study's findings. Reference to findings should always be described as having already happened because the method used to gather the information has been completed.

III. Problems to Avoid

When writing the results section, avoid doing the following :

- Discussing or interpreting your results . Save this for the discussion section of your paper, although where appropriate, you should compare or contrast specific results to those found in other studies [e.g., "Similar to the work of Smith [1990], one of the findings of this study is the strong correlation between motivation and academic achievement...."].

- Reporting background information or attempting to explain your findings. This should have been done in your introduction section, but don't panic! Often the results of a study point to the need for additional background information or to explain the topic further, so don't think you did something wrong. Writing up research is rarely a linear process. Always revise your introduction as needed.

- Ignoring negative results . A negative result generally refers to a finding that does not support the underlying assumptions of your study. Do not ignore them. Document these findings and then state in your discussion section why you believe a negative result emerged from your study. Note that negative results, and how you handle them, can give you an opportunity to write a more engaging discussion section, therefore, don't be hesitant to highlight them.

- Including raw data or intermediate calculations . Ask your professor if you need to include any raw data generated by your study, such as transcripts from interviews or data files. If raw data is to be included, place it in an appendix or set of appendices that are referred to in the text.

- Be as factual and concise as possible in reporting your findings . Do not use phrases that are vague or non-specific, such as, "appeared to be greater than other variables..." or "demonstrates promising trends that...." Subjective modifiers should be explained in the discussion section of the paper [i.e., why did one variable appear greater? Or, how does the finding demonstrate a promising trend?].

- Presenting the same data or repeating the same information more than once . If you want to highlight a particular finding, it is appropriate to do so in the results section. However, you should emphasize its significance in relation to addressing the research problem in the discussion section. Do not repeat it in your results section because you can do that in the conclusion of your paper.

- Confusing figures with tables . Be sure to properly label any non-textual elements in your paper. Don't call a chart an illustration or a figure a table. If you are not sure, go here .

Annesley, Thomas M. "Show Your Cards: The Results Section and the Poker Game." Clinical Chemistry 56 (July 2010): 1066-1070; Bavdekar, Sandeep B. and Sneha Chandak. "Results: Unraveling the Findings." Journal of the Association of Physicians of India 63 (September 2015): 44-46; Burton, Neil et al. Doing Your Education Research Project . Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2008; Caprette, David R. Writing Research Papers. Experimental Biosciences Resources. Rice University; Hancock, Dawson R. and Bob Algozzine. Doing Case Study Research: A Practical Guide for Beginning Researchers . 2nd ed. New York: Teachers College Press, 2011; Introduction to Nursing Research: Reporting Research Findings. Nursing Research: Open Access Nursing Research and Review Articles. (January 4, 2012); Kretchmer, Paul. Twelve Steps to Writing an Effective Results Section. San Francisco Edit ; Ng, K. H. and W. C. Peh. "Writing the Results." Singapore Medical Journal 49 (2008): 967-968; Reporting Research Findings. Wilder Research, in partnership with the Minnesota Department of Human Services. (February 2009); Results. The Structure, Format, Content, and Style of a Journal-Style Scientific Paper. Department of Biology. Bates College; Schafer, Mickey S. Writing the Results. Thesis Writing in the Sciences. Course Syllabus. University of Florida.

Writing Tip

Why Don't I Just Combine the Results Section with the Discussion Section?

It's not unusual to find articles in scholarly social science journals where the author(s) have combined a description of the findings with a discussion about their significance and implications. You could do this. However, if you are inexperienced writing research papers, consider creating two distinct sections for each section in your paper as a way to better organize your thoughts and, by extension, your paper. Think of the results section as the place where you report what your study found; think of the discussion section as the place where you interpret the information and answer the "So What?" question. As you become more skilled writing research papers, you can consider melding the results of your study with a discussion of its implications.

Driscoll, Dana Lynn and Aleksandra Kasztalska. Writing the Experimental Report: Methods, Results, and Discussion. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University.

- << Previous: Insiderness

- Next: Using Non-Textual Elements >>

- Last Updated: Oct 10, 2024 12:29 PM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

Research Paper Writing Guides

Research Paper Results Section

Last updated on: Sep 26, 2024

How To Write The Results Section of A Research Paper | Steps & Tips

By: Donna C.

Reviewed By: Rylee W.

Published on: Jan 9, 2024

Many researchers find themselves at a crossroads when it comes to crafting the results section of their research papers.

It's not just about displaying data; it's about creating a narrative that captivates readers and communicates the significance of your findings.

How do you ensure your data is not just presented but truly understood by your audience?

In this comprehensive guide, we will walk you through the process of writing an effective results section that transforms your research paper .

Whether you're struggling with data interpretation or seeking ways to make your findings resonate, our step-by-step guide will help you create outstanding result sections.

Let’s get started!

On this Page

What is the Result Section of a Research Paper?

The results section of a research paper is a critical component that presents the key findings derived from the study.

It serves as a factual and objective account of the data collected during the research process.

In this section, researchers report their observations and measurements of the hypothesis, often utilizing tables, graphs, or statistical measures to convey the information effectively.

What Does the Results Section of a Research Paper Include?

In the results section, you show off what you found in your research. Here's a quick look at what it includes:

- Data Presentation: Display your information using figures and tables.

- Descriptive Statistics: Use numbers like average and middle values to summarize your data.

- What It Means: Explain what your results say and if there are any patterns.

- Correlations and Relationships: Look for a correlation between two variables or different factors and talk about them.

- Limitations: Mention any problems or limits your study might have.

- Compare with Others: See how your findings relate to what others have discovered before.

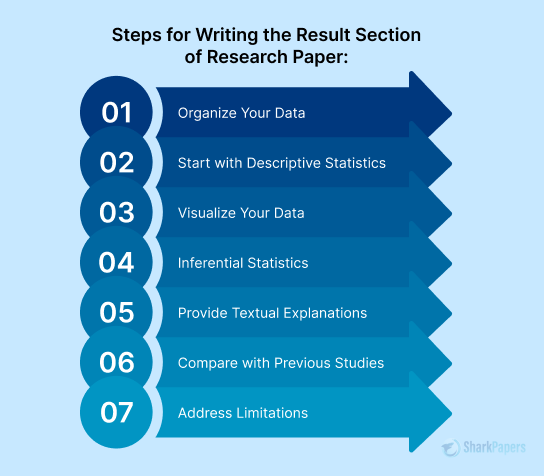

How To Write The Results Section of A Research Paper Step-by-Step

Crafting an effective Results section is a crucial aspect of any research paper. Follow these steps to ensure your findings are presented clearly and concisely:

Step 1: Organize Your Data

Organizing your data is a critical first step in the Results section of a research paper. This involves structuring your raw data in a way that is clear, logical, and easily digestible for your readers.

- Raw Data Arrangement: Group similar data logically, such as by time or experimental conditions.

- Visual Representation: Use tables, graphs, or charts for clarity; pick the format that suits your data best.

- Clarity in Design: Ensure visuals are clear with labels, colors, and consistent formatting.

- Quick Understanding: Aim for simplicity; make sure readers can grasp the main points at a glance.

- Consistency: Keep a consistent writing style across visuals for a cohesive presentation.

Step 2: Start With Descriptive Statistics

In this section, dive into the specifics of your data through systematic description, providing a snapshot that captures both central tendencies and variability.

- Calculate the Mean: Find the average value of your data points, offering a central measure indicative of the overall trend.

- Explore the Median: Identify the middle point of your data, a robust measure that remains unaffected by extreme values.

- Assess Standard Deviation: Understand the dispersion of your data around the mean, highlighting the degree of variability.

Step 3: Visualize Your Data

Enhance understanding by incorporating visual representations. Graphs and charts can convey trends and patterns effectively, providing readers with a more intuitive grasp of your results.

- Select Appropriate Visuals: Choose the right type of graph or chart based on your data—bar charts for comparisons, line graphs for trends, and pie charts for proportions.

- Ensure Clarity: Design visuals with clear labels, legible fonts, and distinctive colors to facilitate easy interpretation.

- Highlight Trends: Emphasize significant trends or patterns in your data, guiding readers to key insights.

Step 4: Inferential Statistics

If applicable, apply inferential statistics to analyze the significance of your findings. Use tests to show statistically meaningful positive and negative results.

- Select Relevant Tests: Choose appropriate statistical tests based on your research question—ANOVA for multiple groups, t-tests for two groups, etc.

- Establish Significance Levels: Define significance levels (usually p-values) to determine whether observed differences are likely due to chance.

Step 5: Provide Textual Explanations

Accompany visual elements with clear and concise textual explanations. Explain the significance of observed trends or patterns in your visuals, ensuring readers grasp their relevance to your research problem.

Acknowledge and explain any unexpected results, offering insights into potential factors or nuances that may have influenced the outcomes.

Always tie your explanations back to your research question, emphasizing how each finding contributes to the broader understanding of the results of your study.

Step 6: Compare with Previous Studies

By discussing similarities, differences, or advancements in knowledge, you can highlight the uniqueness of your contribution to the field.

Summarize relevant findings from the literature review and review articles related to your research problem . Compare or contrast your results with those of previous studies. Discuss similarities and differences, emphasizing the novel aspects of your research.

In the end, identify any contributions your study makes to advancing knowledge in the field. Highlight how your findings build upon or challenge existing understandings.

Step 7: Address Limitations

Acknowledge and address any limitations in your study. Discuss how these limitations may have influenced your results, maintaining transparency about the potential impact on the study's outcomes.

Lastly, propose avenues for future research that could address the identified limitations, offering insights for researchers interested in building upon your study.

By following these steps, you can engage your audience, providing a comprehensive and insightful view of your research findings.

Results Section for Quantitative Research

When crafting the Results section for quantitative research, there are several key qualities that can enhance the clarity, validity, and overall impact of your presentation.

Here are the main qualities to consider for crafting a results section for quantitative research:

- Comprehensive Descriptions: Clearly state what each statistical test or measure represents and how it contributes to your study.

- Appropriate Visual Elements: Ensure that these visuals are accurately labeled, easy to interpret, and directly support the points made in the text.

- Inclusion of Key Statistical Measures: Include essential statistical measures relevant to your study, such as means, standard deviations, p-values, confidence intervals, and effect sizes.

- Concise Interpretation: Highlight the most salient patterns or trends and their implications. Save in-depth interpretation and discussion for the dedicated Discussion section.

Here is an example for quantitative results of a research paper:

Results Section Of A Quantitative Research Paper

Results Section for Qualitative Research

Writing the Results section for qualitative research involves presenting and interpreting the data collected through methods such as interviews, observations, or content analysis.

Here are the main qualities of a results section of qualitative research:

- Participant Voice: Prioritize the voices of the participants. Include direct quotes to give the participants a presence in the Results section.

- Negotiation of Bias: Acknowledge and discuss the potential biases and subjectivities that may have influenced the interpretation of the data.

- Negative Instances: Discuss instances where the data deviate from the identified themes and explore the reasons behind these variations.

- Comparison and Contrast: If applicable, compare and contrast themes across different participant groups, contexts, or time points. This adds depth to the analysis and helps in identifying patterns or variations within the data.

- Transition to Discussion: Conclude the Results section with a seamless transition to the Discussion section. Briefly summarize the main findings and indicate how they will be further explored and interpreted in the subsequent section.

Here is an example for qualitative results of a research paper:

Results Section Of A Qualitative Research Paper

Result Section Examples

Here are some examples for learning how to write the results section of a research paper.

Results Section Of A Research Paper Example

Summary Of Results In Research Example

Research Findings Example Pdf

How To Write The Results Section of A Research Paper APA

Mistakes to Avoid When Writing Results Section of Research Paper

Understanding the Results section of a research paper needs carefulness and attention to detail. To present your findings well, avoid these common mistakes:

|

|

| Focus on key findings; use appendices for extensive data. |

| Complement visuals with interpretations and context in the text. |

| Ensure a structured approach: describe data first, then interpret. |

| Acknowledge anomalies and discuss potential reasons behind them. |

| Simplify statistical terms; provide clear explanations. |

| Design visuals with simplicity, clarity, and appropriate labeling. |

| Constantly reference back to the research question for focus. |

| Be transparent about limitations and discuss their potential impact. |

| Stick to a balanced and honest representation of findings. |

| Conclude by outlining potential directions for further investigation. |

Wrapping up, mastering the results section demands precision and clarity. By sidestepping common mistakes, you enhance the credibility of your findings.

Keep it simple, stay focused on your main question, and be transparent about limitations.

But still, if you think this work is too much for you, turn to the best paper writing service online .

We are experts who can craft an outstanding research paper as well as different sections of your research paper.

Visit our platform and get research papers for sale without breaking the bank!

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the difference between the results and the discussion section.

Results present raw data and findings, while Discussion interprets and contextualizes results, providing explanations and exploring broader significance. Results are about "what," Discussion is about "why" and "what it means."

How Long Should the Results Section a Research Paper Be?

In general, the ideal length of this section is often several pages long, but there's no fixed rule. It's essential to balance thoroughness with conciseness.

Donna writes on a broad range of topics, but she is mostly passionate about social issues, current events, and human-interest stories. She has received high praise for her writing from both colleagues and readers alike. Donna is known in her field for creating content that is not only professional but also captivating.

Was This Blog Helpful?

Keep reading.

- Learning How to Write a Research Paper: Step-by-Step Guide

- Best 300+ Ideas For Research Paper Topics in 2024

- A Complete Guide to Help You Write a Research Proposal

- The Definitive Guide on How to Start a Research Paper

- How To Write An Introduction For A Research Paper - A Complete Guide

- Learn How To Write An Abstract For A Research Paper with Examples and Tips

- How to Write a Literature Review for a Research Paper | A Complete Guide

- How To Write The Methods Section of A Research Paper

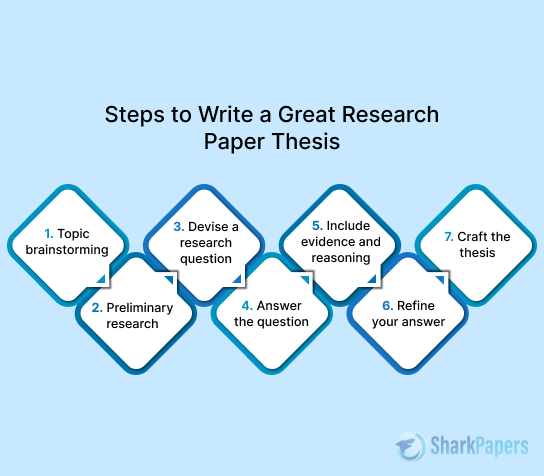

- How to Write a Research Paper Thesis: A Detailed Guide

- How to Write a Research Paper Title That Stands Out

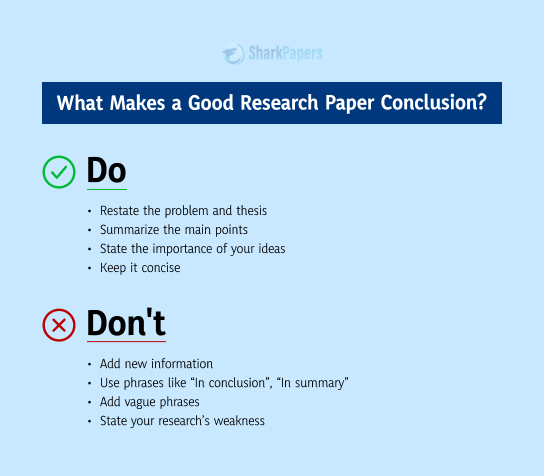

- A Detailed Guide on How To Write a Conclusion for a Research Paper

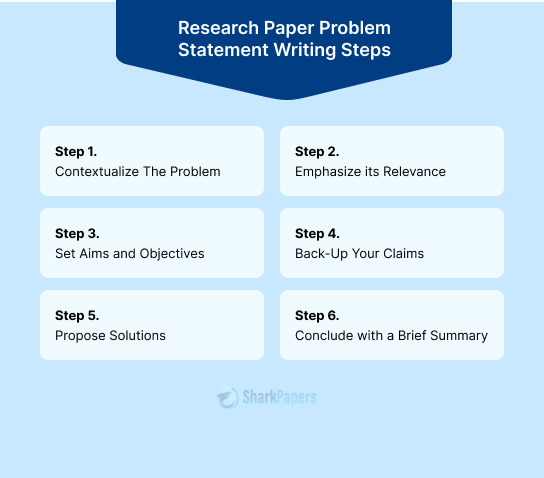

- How to Write a Problem Statement for a Research Paper: An Easy Guide

- How to Find Credible Sources for a Research Paper

- A Detailed Guide: How to Write a Discussion for a Research Paper

)

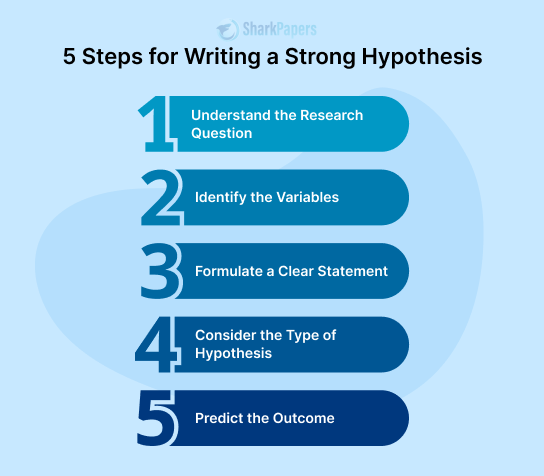

- How To Write A Hypothesis In A Research Paper - A Simple Guide

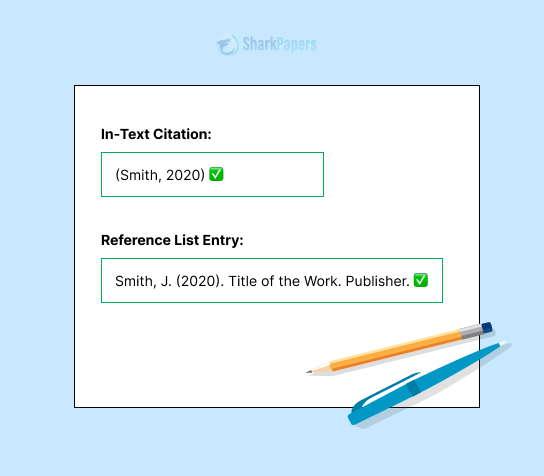

- Learn How To Cite A Research Paper in Different Formats: The Basics

- The Ultimate List of Ethical Research Paper Topics in 2024

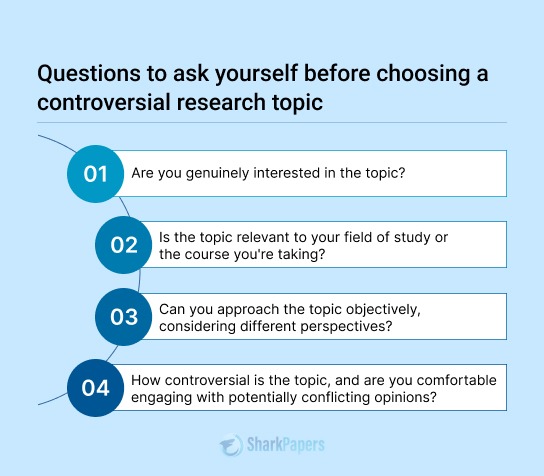

- 150+ Controversial Research Paper Topics to Get You Started

- How to Edit Research Papers With Precision: A Detailed Guide

- A Comprehensive List of Argumentative Research Paper Topics

- A Detailed List of Amazing Art Research Paper Topics