Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

Science, technology and society articles from across Nature Portfolio

Latest research and reviews.

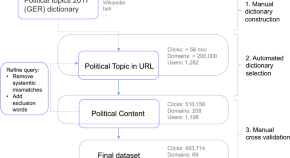

More than news! Mapping the deliberative potential of a political online ecosystem with digital trace data

- Lisa Oswald

Anticompetitive effect of drug name trademark registration: lessons from China

- Xiaoting Song

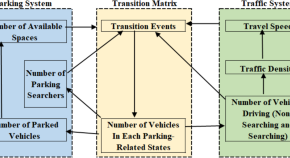

Urban traffic-parking system dynamics model with macroscopic properties: a comparative study between Shanghai and Zurich

- Biruk Gebremedhin Mesfin

Unveiling the origins of non-performance-oriented behavior in China’s local governments: a game theory perspective on the performance-based promotion system

- Huping Shang

- Hongmei Liu

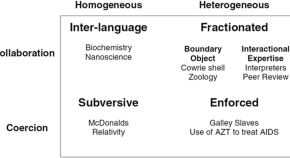

An STS analysis of a digital humanities collaboration: trading zones, boundary objects, and interactional expertise in the DECRYPT project

- Benedek Láng

- Beáta Megyesi

Exploration of the creative processes in animals, robots, and AI: who holds the authorship?

- Cédric Sueur

- Jessica Lombard

News and Comment

Paris suv policy and urban sustainability.

- Zaheer Allam

Dangers of speech technology for workplace diversity

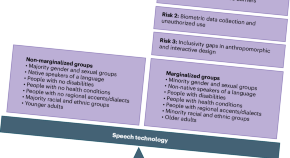

Speech technology offers many applications to enhance employee productivity and efficiency. Yet new dangers arise for marginalized groups, potentially jeopardizing organizational efforts to promote workplace diversity. Our analysis delves into three critical risks of speech technology and offers guidance for mitigating these risks responsibly.

- Mike Horia Mihail Teodorescu

- Mingang K. Geiger

Safeguarding young users on social media through academic oversight

The EU commission’s Digital Services Act aims to protect children and adolescents from psychological harm on social media platforms. This initiative needs to be carried out in close cooperation between the EU commission and independent academics.

- Christian Montag

- Peter J. Schulz

- Benjamin Becker

Hybrid intelligence for reconciling biodiversity and productivity in agriculture

Hybrid intelligence — arising from the sensible, targeted fusion of human minds and cutting-edge computational systems — holds great potential for enhancing the sustainability of agriculture. Leveraging the combined strengths of both collective human and artificial intelligence helps identify and stress-test pathways towards the reconciliation of biodiversity and productivity.

How to transition from academia to industry and back

Researchers have a wide variety of choices when it comes to careers. Often, post-PhD, we leave academic research for industry. But it is also possible to transition back, when done carefully. In this how-to, I outline how to transition between industry and academic research and vice versa.

- Cassandra L. Jacobs

Virtual reality for nature experiences

Given the increasing sophistication of virtual reality systems in providing immersive nature experiences, there is the potential for analogous health benefits to those that arise from real nature experiences. We call for research to better understand the human–nature–technology interaction to overcome potential pitfalls of the technology and design tailored virtual experiences that can deliver health outcomes and wellbeing across society.

- Violeta Berdejo-Espinola

- Renee Zahnow

- Richard A. Fuller

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Advertisement

Data science: a game changer for science and innovation

- Regular Paper

- Open access

- Published: 19 April 2021

- Volume 11 , pages 263–278, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Valerio Grossi 1 ,

- Fosca Giannotti 1 ,

- Dino Pedreschi 2 ,

- Paolo Manghi 3 ,

- Pasquale Pagano 3 &

- Massimiliano Assante 3

14k Accesses

19 Citations

57 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

This paper shows data science’s potential for disruptive innovation in science, industry, policy, and people’s lives. We present how data science impacts science and society at large in the coming years, including ethical problems in managing human behavior data and considering the quantitative expectations of data science economic impact. We introduce concepts such as open science and e-infrastructure as useful tools for supporting ethical data science and training new generations of data scientists. Finally, this work outlines SoBigData Research Infrastructure as an easy-to-access platform for executing complex data science processes. The services proposed by SoBigData are aimed at using data science to understand the complexity of our contemporary, globally interconnected society.

Similar content being viewed by others

What Is Data Science?

Introduction to applied data science, data science.

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction: from data to knowledge

Data science is an interdisciplinary and pervasive paradigm where different theories and models are combined to transform data into knowledge (and value). Experiments and analyses over massive datasets are functional not only to the validation of existing theories and models but also to the data-driven discovery of patterns emerging from data, which can help scientists in the design of better theories and models, yielding a deeper understanding of the complexity of the social, economic, biological, technological, cultural, and natural phenomenon. The products of data science are the result of re-interpreting available data for analysis goals that differ from the original reasons motivating data collection. All these aspects are producing a change in the scientific method, in research and in the way our society makes decisions [ 2 ].

Data science emerges to concurring facts: (i) the advent of big data that provides the critical mass of actual examples to learn from, (ii) the advances in data analysis and learning techniques that can produce predictive models and behavioral patterns from big data, and (iii) the advances in high-performance computing infrastructures that make it possible to ingest and manage big data and perform complex analysis [ 16 ].

Paper organization Section 2 discusses how data science impacts our science and society at large in the coming years. Section 3 outlines the main issues related to the ethical problems in studying human behaviors that data science introduces. In Sect. 4 , we show how concepts such as open science and e-infrastructure are effective tools for supporting, disseminating ethical uses of the data, and training new generations of data scientists. We will illustrate the importance of an open data science with examples provided later in the paper. Finally, we show some use cases of data science through thematic environments that bind the datasets with social mining methods.

2 Data science for society, science, industry and business

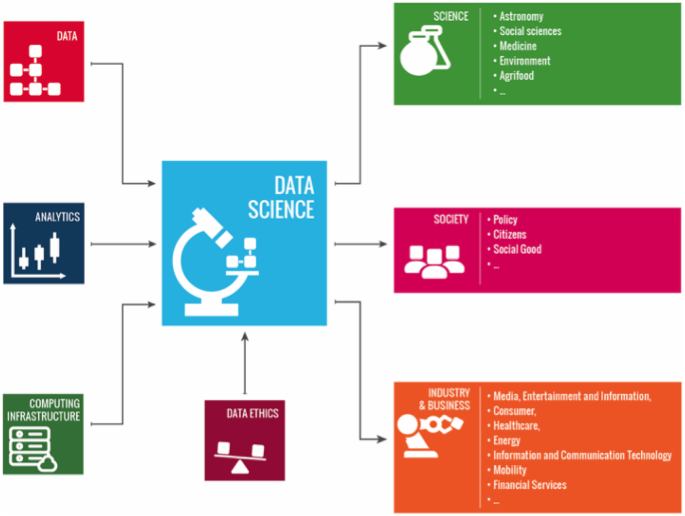

Data science as an ecosystem: on the left, the figure shows the main components enabling data science (data, analytical methods, and infrastructures). On the right, we can find the impact of data science into society, science, and business. All the activities related to data science should be done under rigid ethical principles

The quality of business decision making, government administration, and scientific research can potentially be improved by analyzing data. Data science offers important insights into many complicated issues, in many instances, with remarkable accuracy and timeliness.

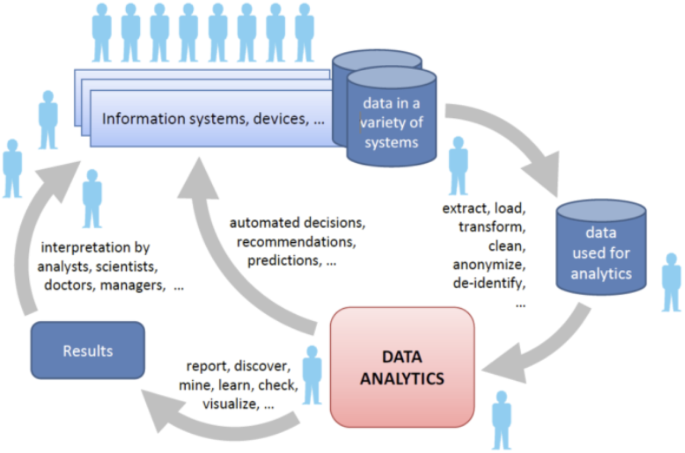

The data science pipeline starts with raw data and transforms them into data used for analytics. The next step is to transform these data into knowledge through analytical methods and then provide results and evaluation measures

As shown in Fig. 1 , data science is an ecosystem where the following scientific, technological, and socioeconomic factors interact:

Data Availability of data and access to data sources;

Analytics & computing infrastructures Availability of high performance analytical processing and open-source analytics;

Skills Availability of highly and rightly skilled data scientists and engineers;

Ethical & legal aspects Availability of regulatory environments for data ownership and usage, data protection and privacy, security, liability, cybercrime, and intellectual property rights;

Applications Business and market ready applications;

Social aspects Focus on major societal global challenges.

Data science envisioned as the intersection between data mining, big data analytics, artificial intelligence, statistical modeling, and complex systems is capable of monitoring data quality and analytical processes results transparently. If we want data science to face the global challenges and become a determinant factor of sustainable development, it is necessary to push towards an open global ecosystem for science, industrial, and societal innovation [ 48 ]. We need to build an ecosystem of socioeconomic activities, where each new idea, product, and service create opportunities for further purposes, and products. An open data strategy, innovation, interoperability, and suitable intellectual property rights can catalyze such an ecosystem and boost economic growth and sustainable development. This strategy also requires a “networked thinking” and a participatory, inclusive approach.

Data are relevant in almost all the scientific disciplines, and a data-dominated science could lead to the solution of problems currently considered hard or impossible to tackle. It is impossible to cover all the scientific sectors where a data-driven revolution is ongoing; here, we shall only provide just a few examples.

The Sloan Digital Sky Survey Footnote 1 has become a central resource for astronomers over the world. Astronomy is being transformed from the one where taking pictures of the sky was a large part of an astronomer’s job, to the one where the images are already in a database, and the astronomer’s task is to find interesting objects and phenomenon in the database. In biological sciences, data are stored in public repositories. There is an entire discipline of bioinformatics that is devoted to the analysis of such data. Footnote 2 Data-centric approaches based on personal behaviors can also support medical applications analyzing data at both human behavior levels and lower molecular ones. For example, integrating genome data of medical reactions with the habits of the users, enabling a computational drug science for high-precision personalized medicine. In humans, as in other organisms, most cellular components exert their functions through interactions with other cellular components. The totality of these interactions (representing the human “interactome”) is a network with hundreds of thousand nodes and a much larger number of links. A disease is rarely a consequence of an abnormality in a single gene. Instead, the disease phenotype is a reflection of various pathological processes that interact in a complex network. Network-based approaches can have multiple biological and clinical applications, especially in revealing the mechanisms behind complex diseases [ 6 ].

Now, we illustrate the typical data science pipeline [ 50 ]. People, machines, systems, factories, organizations, communities, and societies produce data. Data are collected in every aspect of our life, when: we submit a tax declaration; a customer orders an item online; a social media user posts a comment; a X-ray machine is used to take a picture; a traveler sends a review on a restaurant; a sensor in a supply chain sends an alert; or a scientist conducts an experiment. This huge and heterogeneous quantity of data needs to be extracted, loaded, understood, transformed, and in many cases, anonymized before they may be used for analysis. Analysis results include routines, automated decisions, predictions, and recommendations, and outcomes that need to be interpreted to produce actions and feedback. Furthermore, this scenario must also consider ethical problems in managing social data. Figure 2 depicts the data science pipeline. Footnote 3 Ethical aspects are important in the application of data science in several sectors, and they are addressed in Sect. 3 .

2.1 Impact on society

Data science is an opportunity for improving our society and boosting social progress. It can support policymaking; it offers novel ways to produce high-quality and high-precision statistical information and empower citizens with self-awareness tools. Furthermore, it can help to promote ethical uses of big data.

Modern cities are perfect environments densely traversed by large data flows. Using traffic monitoring systems, environmental sensors, GPS individual traces, and social information, we can organize cities as a collective sharing of resources that need to be optimized, continuously monitored, and promptly adjusted when needed. It is easy to understand the potentiality of data science by introducing terms such as urban planning , public transportation , reduction of energy consumption , ecological sustainability, safety , and management of mass events. These terms represent only the front line of topics that can benefit from the awareness that big data might provide to the city stakeholders [ 22 , 27 , 29 ]. Several methods allowing human mobility analysis and prediction are available in the literature: MyWay [ 47 ] exploits individual systematic behaviors to predict future human movements by combining individual and collective learned models. Carpooling [ 22 ] is based on mobility data from travelers in a given territory and constructs a network of potential carpooling users, by exploiting topological properties, highlighting sub-populations with higher chances to create a carpooling community and the propensity of users to be either drivers or passengers in a shared car. Event attendance prediction [ 13 ] analyzes users’ call habits and classifies people into behavioral categories, dividing them among residents, commuters, and visitors and allows to observe the variety of behaviors of city users and the attendance in big events in cities.

Electric mobility is expected to gain importance for the world. The impact of a complete switch to electric mobility is still under investigation, and what appears to be critical is the intensity of flows due to charge (and fast recharge) systems that may challenge the stability of the power network. To avoid instabilities regarding the charging infrastructure, an accurate prediction of power flows associated with mobility is needed. The use of personal mobility data can estimate the mobility flow and simulate the impact of different charging behavioral patterns to predict power flows and optimize the position of the charging infrastructures [ 25 , 49 ]. Lorini et al. [ 26 ] is an example of an urban flood prediction that integrates data provided by CEM system Footnote 4 and Twitter data. Twitter data are processed using massive multilingual approaches for classification. The model is a supervised model which requires a careful data collection and validation of ground truth about confirmed floods from multiple sources.

Another example of data science for society can be found in the development of applications with functions aimed directly at the individual. In this context, concepts such as personal data stores and personal data analytics are aimed at implementing a new deal on personal data, providing a user-centric view where data are collected, integrated and analyzed at the individual level, and providing the user with better awareness of own behavioral, health, and consumer profiles. Within this user-centric perspective, there is room for an even broader market of business applications, such as high-precision real-time targeted marketing, e.g., self-organizing decision making to preserve desired global properties, and sustainability of the transportation or the healthcare system. Such contexts emphasize two essential aspects of data science: the need for creativeness to exploit and combine the several data sources in novel ways and the need to give awareness and control of the personal data to the users that generate them, to sustain a transparent, trust-based, crowd-sourced data ecosystem [ 19 ].

The impact of online social networks in our society has changed the mechanisms behind information spreading and news production. The transformation of media ecosystems and news consumption are having consequences in several fields. A relevant example is the impact of misinformation on society, as for the Brexit referendum when the massive diffusion of fake news has been considered one of the most relevant factors of the outcome of this political event. Examples of achievements are provided by the results regarding the influence of external news media on polarization in online social networks. These achievements indicate that users are highly polarized towards news sources, i.e., they cite (and tend to cite) sources that they identify as ideologically similar to them. Other results regard echo chambers and the role of social media users: there is a strong correlation between the orientation of the content produced and consumed. In other words, an opinion “echoes” back to the user when others are sharing it in the “chamber” (i.e., the social network around the user) [ 36 ]. Other results worth mentioning regard efforts devoted to uncovering spam and bot activities in stock microblogs on Twitter: taking inspiration from biological DNA, the idea is to model the online users’ behavior through strings of characters representing sequences of online users’ actions. As a result of the following papers, [ 11 , 12 ] report that 71% of suspicious users were classified as bots; furthermore, 37% of them also got suspended by Twitter few months after our investigation. Several approaches can be found in the literature. However, they generally display some limitations. Some of them work only on some of the features of the diffusion of misinformation (bot detections, segregation of users due to their opinions or other social analysis), or there is a lack of comprehensive frameworks for interpreting results. While the former case is somehow due to the innovation of the research field and it is explainable, the latter showcases a more fundamental need, as, without strict statistical validation, it is hard to state which are the crucial elements that permit a well-grounded description of a system. For avoiding fake news diffusion, we can state that building a comprehensive fake news dataset providing all information about publishers, shared contents, and the engagements of users over space and time, together with their profile stories, can help the development of innovative and effective learning models. Both unsupervised and supervised methods will work together to identify misleading information. Multidisciplinary teams made up of journalists, linguists, and behavioral scientists and similar will be needed to identify what amounts to information warfare campaigns. Cyberwarfare and information warfare will be two of the biggest threats the world will face in the 21st Century.

Social sensing methods collect data produced by digital citizens, by either opportunistic or participatory crowd-sensing, depending on users’ awareness of their involvement. These approaches present a variety of technological and ethical challenges. An example is represented by Twitter Monitor [ 10 ], that is crowd-sensing tool designed to access Twitter streams through the Twitter Streaming API. It allows launching parallel listening for collecting different sets of data. Twitter Monitor represents a tool for creating services for listening campaigns regarding relevant events such as political elections, natural and human-made disasters, popular national events, etc. [ 11 ]. This campaign can be carried out, specifying keywords, accounts, and geographical areas of interest.

Nowcasting Footnote 5 financial and economic indicators focus on the potential of data science as a proxy for well-being and socioeconomic applications. The development of innovative research methods has demonstrated that poverty indicators can be approximated by social and behavioral mobility metrics extracted from mobile phone data and GPS data [ 34 ]; and the Gross Domestic Product can be accurately nowcasted by using retail supermarket market data [ 18 ]. Furthermore, nowcasting of demographic aspects of territory based on Twitter data [ 1 ] can support official statistics, through the estimation of location, occupation, and semantics. Networks are a convenient way to represent the complex interaction among the elements of a large system. In economics, networks are gaining increasing attention because the underlying topology of a networked system affects the aggregate output, the propagation of shocks, or financial distress; or the topology allows us to learn something about a node by looking at the properties of its neighbors. Among the most investigated financial and economic networks, we cite a work that analyzes the interbank systems, the payment networks between firms, the banks-firms bipartite networks, and the trading network between investors [ 37 ]. Another interesting phenomenon is the advent of blockchain technology that has led to the innovation of bitcoin crypto-currency [ 31 ].

Data science is an excellent opportunity for policy, data journalism, and marketing. The online media arena is now available as a real-time experimenting society for understanding social mechanisms, like harassment, discrimination, hate, and fake news. In our vision, the use of data science approaches is necessary for better governance. These new approaches integrate and change the Official Statistics representing a cheaper and more timely manner of computing them. The impact of data science-driven applications can be particularly significant when the applications help to build new infrastructures or new services for the population.

The availability of massive data portraying soccer performance has facilitated recent advances in soccer analytics. Rossi et al. [ 42 ] proposed an innovative machine learning approach to the forecasting of non-contact injuries for professional soccer players. In [ 3 ], we can find the definition of quantitative measures of pressing in defensive phases in soccer. Pappalardo et al. [ 33 ] outlined the automatic and data-driven evaluation of performance in soccer, a ranking system for soccer teams. Sports data science is attracting much interest and is now leading to the release of a large and public dataset of sports events.

Finally, data science has unveiled a shift from population statistics to interlinked entities statistics, connected by mutual interactions. This change of perspective reveals universal patterns underlying complex social, economic, technological, and biological systems. It is helpful to understand the dynamics of how opinions, epidemics, or innovations spread in our society, as well as the mechanisms behind complex systemic diseases, such as cancer and metabolic disorders revealing hidden relationships between them. Considering diffusive models and dynamic networks, NDlib [ 40 ] is a Python package for the description, simulation, and observation of diffusion processes in complex networks. It collects diffusive models from epidemics and opinion dynamics and allows a scientist to compare simulation over synthetic systems. For community discovery, two tools are available for studying the structure of a community and understand its habits: Demon [ 9 ] extracts ego networks (i.e., the set of nodes connected to an ego node) and identifies the real communities by adopting a democratic, bottom-up merging approach of such structures. Tiles [ 41 ] is dedicated to dynamic network data and extracts overlapping communities and tracks their evolution in time following an online iterative procedure.

2.2 Impact on industry and business

Data science can create an ecosystem of novel data-driven business opportunities. As a general trend across all sectors, massive quantities of data will be made accessible to everybody, allowing entrepreneurs to recognize and to rank shortcomings in business processes, to spot potential threads and win-win situations. Ideally, every citizen could establish from these patterns new business ideas. Co-creation enables data scientists to design innovative products and services. The value of joining different datasets is much larger than the sum of the value of the separated datasets by sharing data of various nature and provenance.

The gains from data science are expected across all sectors, from industry and production to services and retail. In this context, we cite several macro-areas where data science applications are especially promising. In energy and environment , the digitization of the energy systems (from production to distribution) enables the acquisition of real-time, high-resolution data. Coupled with other data sources, such as weather data, usage patterns, and market data (accompanied by advanced analytics), efficiency levels can be increased immensely. The positive impact to the environment is also enhanced by geospatial data that help to understand how our planet and its climate are changing and to confront major issues such as global warming, preservation of the species, the role and effects of human activities.

The manufacturing and production sector with the growing investments into Industry 4.0 and smart factories with sensor-equipped machinery that are both intelligent and networked (see internet of things . Cyber-physical systems ) will be one of the major producers of data in the world. The application of data science into this sector will bring efficiency gains and predictive maintenance. Entirely new business models are expected since the mass production of individualized products becomes possible where consumers may have direct access to influence and control.

As already stated in Sect. 2.1 , data science will contribute to increasing efficiency in public administrations processes and healthcare. In the physical and the cyber-domain, security will be enhanced. From financial fraud to public security, data science will contribute to establishing a framework that enables a safe and secure digital economy. Big data exploitation will open up opportunities for innovative, self-organizing ways of managing logistical business processes. Deliveries could be based on predictive monitoring, using data from stores, semantic product memories, internet forums, and weather forecasts, leading to both economic and environmental savings. Let us also consider the impact of personalized services for creating real experiences for tourists. The analysis of real-time and context-aware data (with the help of historical and cultural heritage data) will provide customized information to each tourist, and it will contribute to the better and more efficient management of the whole tourism value chain.

3 Data science ethics

Data science creates great opportunities but also new risks. The use of advanced tools for data analysis could expose sensitive knowledge of individual persons and could invade their privacy. Data science approaches require access to digital records of personal activities that contain potentially sensitive information. Personal information can be used to discriminate people based on their presumed characteristics. Data-driven algorithms yield classification and prediction models of behavioral traits of individuals, such as credit score, insurance risk, health status, personal preferences, and religious, ethnic, or political orientation, based on personal data disseminated in the digital environment by users (with or often without their awareness). The achievements of data science are the result of re-interpreting available data for analysis goals that differ from the original reasons motivating data collection. For example, mobile phone call records are initially collected by telecom operators for billing and operational aims, but they can be used for accurate and timely demography and human mobility analysis at a country or regional scale. This re-purposing of data clearly shows the importance of legal compliance and data ethics technologies and safeguards to protect privacy and anonymity; to secure data; to engage users; to avoid discrimination and misuse; to account for transparency; and to the purpose of seizing the opportunities of data science while controlling the associated risks.

Several aspects should be considered to avoid to harm individual privacy. Ethical elements should include the: (i) monitoring of the compliance of experiments, research protocols, and applications with ethical and juridical standards; (ii) developing of big data analytics and social mining tools with value-sensitive design and privacy-by-design methodologies; (iii) boosting of excellence and international competitiveness of Europe’s big data research in safe and fair use of big data for research. It is essential to highlight that data scientists using personal and social data also through infrastructures have the responsibility to get acquainted with the fundamental ethical aspects relating to becoming a “data controller.” This aspect has to be considered to define courses for informing and training data scientists about the responsibilities, the possibilities, and the boundaries they have in data manipulation.

Recalling Fig. 2 , it is crucial to inject into the data science pipeline the ethical values of fairness : how to avoid unfair and discriminatory decisions; accuracy : how to provide reliable information; confidentiality : how to protect the privacy of the involved people and transparency : how to make models and decisions comprehensible to all stakeholders. This value-sensitive design has to be aimed at boosting widespread social acceptance of data science, without inhibiting its power. Finally, it is essential to consider also the impact of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) on (i) companies’ duties and how these European companies should comply with the limits in data manipulation the Regulation requires; and on (ii) researchers’ duties and to highlight articles and recitals which specifically mention and explain how research is intended in GDPR’s legal system.

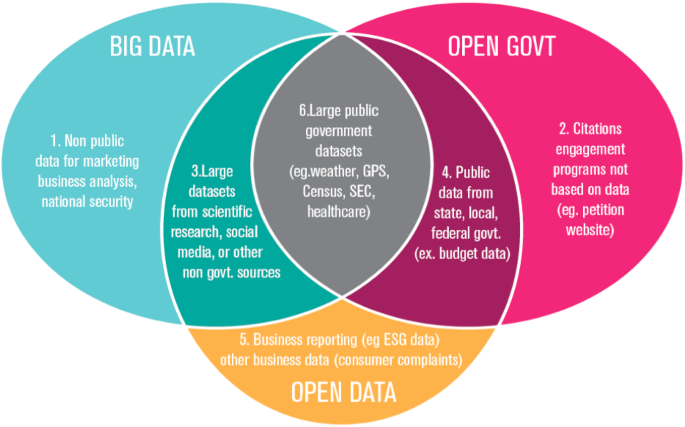

The relationship between big and open data and how they relate to the broad concept of open government

We complete this section with another important aspect related to open data, i.e., accessible public data that people, companies, and organizations can use to launch new ventures, analyze patterns and trends, make data-driven decisions, and solve complex problems. All the definitions of open data include two features: (i) the data must be publicly available for anyone to use, and (ii) data must be licensed in a way that allows for its reuse. All over the world, initiatives are launched to make data open by government agencies and public organizations; listing them is impossible, but an UN initiative has to be mentioned. Global Pulse Footnote 6 meant to implement the vision for a future in which big data is harnessed safely and responsibly as a public good.

Figure 3 shows the relationships between open data and big data. Currently, the problem is not only that government agencies (and some business companies) are collecting personal data about us, but also that we do not know what data are being collected and we do not have access to the information about ourselves. As reported by the World Economic forum in 2013, it is crucial to understand the value of personal data to let the users make informed decisions. A new branch of philosophy and ethics is emerging to handle personal data related issues. On the one hand, in all cases where the data might be used for the social good (i.e., medical research, improvement of public transports, contrasting epidemics), and understanding the personal data value means to correctly evaluate the balance between public benefits and personal loss of protection. On the other hand, when data are aimed to be used for commercial purposes, the value mentioned above might instead translate into simple pricing of personal information that the user might sell to a company for its business. In this context, discrimination discovery consists of searching for a-priori unknown contexts of suspect discrimination against protected-by-law social groups, by analyzing datasets of historical decision records. Machine learning and data mining approaches may be affected by discrimination rules, and these rules may be deeply hidden within obscure artificial intelligence models. Thus, discrimination discovery consists of understanding whether a predictive model makes direct or indirect discrimination. DCube [ 43 ] is a tool for data-driven discrimination discovery, a library of methods on fairness analysis.

It is important to evaluate how a mining model or algorithm takes its decision. The growing field of methods for explainable machine learning provides and continuously expands a set of comprehensive tool-kits [ 21 ]. For example, X-Lib is a library containing state-of-the-art explanation methods organized within a hierarchical structure and wrapped in a similar fashion way such that they can be easily accessed and used from different users. The library provides support for explaining classification on tabular data and images and for explaining the logic of complex decision systems. X-Lib collects, among the others, the following collection of explanation methods: LIME [ 38 ], Anchor [ 39 ], DeepExplain that includes Saliency maps [ 44 ], Gradient * Input, Integrated Gradients, and DeepLIFT [ 46 ]. Saliency method is a library containing code for SmoothGrad [ 45 ], as well as implementations of several other saliency techniques: Vanilla Gradients, Guided Backpropogation, and Grad-CAM. Another improvement in this context is the use of robotics and AI in data preparation, curation, and in detecting bias in data, information and knowledge as well as in the misuse and abuse of these assets when it comes to legal, privacy, and ethical issues and when it comes to transparency and trust. We cannot rely on human beings to do these tasks. We need to exploit the power of robotics and AI to help provide the protections required. Data and information lawyers will play a key role in legal and privacy issues, ethical use of these assets, and the problem of bias in both algorithms and the data, information, and knowledge used to develop analytics solutions. Finally, we can state that data science can help to fill the gap between legislators and technology.

4 Big data ecosystem: the role of research infrastructures

Research infrastructures (RIs) play a crucial role in the advent and development of data science. A social mining experiment exploits the main components of data science depicted in Fig. 1 (i.e., data, infrastructures, analytical methods) to enable multidisciplinary scientists and innovators to extract knowledge and to make the experiment reusable by the scientific community, innovators providing an impact on science and society.

Resources such as data and methods help domain and data scientists to transform research or an innovation question into a responsible data-driven analytical process. This process is executed onto the platform, thus supporting experiments that yield scientific output, policy recommendations, or innovative proofs-of-concept. Furthermore, an operational ethical board’s stewardship is a critical factor in the success of a RI.

An infrastructure typically offers easy-to-use means to define complex analytical processes and workflows , thus bridging the gap between domain experts and analytical technology. In many instances, domain experts may become a reference for their scientific communities, thus facilitating new users engagement within the RI activities. As a collateral feedback effect, experiments will generate new relevant data, methods, and workflows that can be integrated into the platform by data scientists, contributing to the resource expansion of the RI. An experiment designed in a node of the RI and executed on the platform returns its results to the entire RI community.

Well defined thematic environments amplify new experiments achievements towards the vertical scientific communities (and potential stakeholders) by activating appropriate dissemination channels.

4.1 The SoBigData Research Infrastructure

The SoBigData Research Infrastructure Footnote 7 is an ecosystem of human and digital resources, comprising data scientists, analytics, and processes. As shown in Fig. 4 , SoBigData is designed to enable multidisciplinary scientists and innovators to realize social mining experiments and to make them reusable by the scientific communities. All the components have been introduced for implementing data science from raw data management to knowledge extraction, with particular attention to legal and ethical aspects as reported in Fig. 1 . SoBigData supports data science serving a cross-disciplinary community of data scientists studying all the elements of societal complexity from a data- and model-driven perspective.

Currently, SoBigData includes scientific, industrial, and other stakeholders. In particular, our stakeholders are data analysts and researchers (35.6%), followed by companies (33.3%) and policy and lawmakers (20%). The following sections provide a short but comprehensive overview of the services provided by SoBigData RI with special attention on supporting ethical and open data science [ 15 , 16 ].

4.1.1 Resources, facilities, and access opportunities

Over the past decade, Europe has developed world-leading expertise in building and operating e-infrastructures. They are large-scale, federated and distributed online research environments through which researchers can share access to scientific resources (including data, instruments, computing, and communications), regardless of their location. They are meant to support unprecedented scales of international collaboration in science, both within and across disciplines, investing in economy-of-scale and common behavior, policies, best practices, and standards. They shape up a common environment where scientists can create , validate , assess , compare , and share their digital results of science, such as research data and research methods, by using a common “digital laboratory” consisting of agreed-on services and tools.

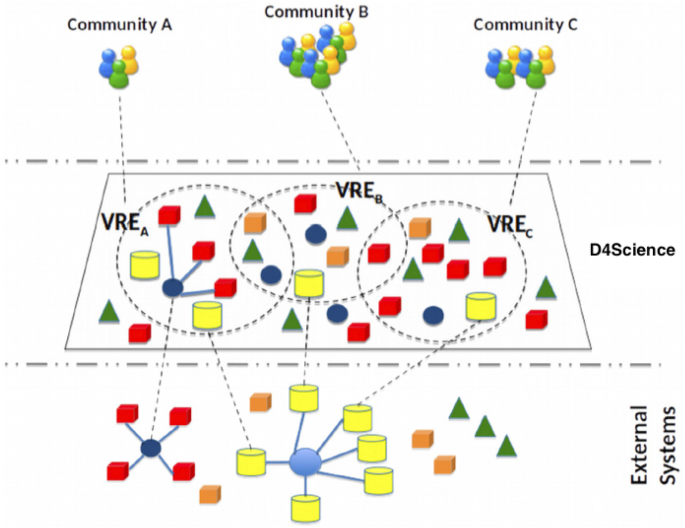

The SoBigData Research Infrastructure: an ecosystem of human and digital resources, comprising data scientists, analytical methods, and processes. SoBigData enables multidisciplinary scientists and innovators to carry out experiments and to make them reusable by the community

However, the implementation of workflows, possibly following Open Science principles of reproducibility and transparency, is hindered by a multitude of real-world problems. One of the most prominent is that e-infrastructures available to research communities today are far from being well-designed and consistent digital laboratories, neatly designed to share and reuse resources according to common policies, data models, standards, language platforms, and APIs. They are instead “patchworks of systems,” assembling online tools, services, and data sources and evolving to match the requirements of the scientific process, to include new solutions. The degree of heterogeneity excludes the adoption of uniform workflow management systems, standard service-oriented approaches, routine monitoring and accounting methods. The realization of scientific workflows is typically realized by writing ad hoc code, manipulating data on desktops, alternating the execution of online web services, sharing software libraries implementing research methods in different languages, desktop tools, web-accessible execution engines (e.g., Taverna, Knime, Galaxy).

The SoBigData e-infrastructure is based on D4Science services, which provides researchers and practitioners with a working environment where open science practices are transparently promoted, and data science practices can be implemented by minimizing the technological integration cost highlighted above.

D4Science is a deployed instance of the gCube Footnote 8 technology [ 4 ], a software conceived to facilitate the integration of web services, code, and applications as resources of different types in a common framework, which in turn enables the construction of Virtual Research Environments (VREs) [ 7 ] as combinations of such resources (Fig. 5 ). As there is no common framework that can be trusted enough, sustained enough, to convince resource providers that converging to it would be a worthwhile effort, D4Science implements a “system of systems.” In such a framework, resources are integrated with minimal cost, to gain in scalability, performance, accounting, provenance tracking, seamless integration with other resources, visibility to all scientists. The principle is that the cost of “participation” to the framework is on the infrastructure rather than on resource providers. The infrastructure provides the necessary bridges to include and combine resources that would otherwise be incompatible.

D4Science: resources from external systems, virtual research environments, and communities

More specifically, via D4Science, SoBigData scientists can integrate and share resources such as datasets, research methods, web services via APIs, and web applications via Portlets. Resources can then be integrated, combined, and accessed via VREs, intended as web-based working environments tailored to support the needs of their designated communities, each working on a research question. Research methods are integrated as executable code, implementing WPS APIs in different programming languages (e.g., Java, Python, R, Knime, Galaxy), which can be executed via the Data Miner analytics platform in parallel, transparently to the users, over powerful and extensible clusters, and via simple VRE user interfaces. Scientists using Data Miner in the context of a VRE can select and execute the available methods and share the results with other scientists, who can repeat or reproduce the experiment with a simple click.

D4Science VREs are equipped with core services supporting data analysis and collaboration among its users: ( i ) a shared workspace to store and organize any version of a research artifact; ( ii ) a social networking area to have discussions on any topic (including working version and released artifacts) and be informed on happenings; ( iii ) a Data Miner analytics platform to execute processing tasks (research methods) either natively provided by VRE users or borrowed from other VREs to be applied to VRE users’ cases and datasets; and iv ) a catalogue-based publishing platform to make the existence of a certain artifact public and disseminated. Scientists operating within VREs use such facilities continuously and transparently track the record of their research activities (actions, authorship, provenance), as well as products and links between them (lineage) resulting from every phase of the research life cycle, thus facilitating publishing of science according to Open Science principles of transparency and reproducibility [ 5 ].

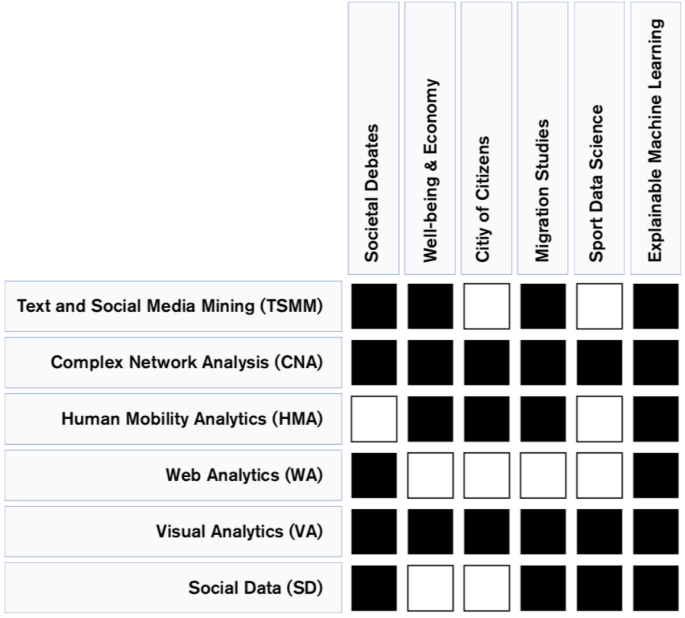

Today, SoBigData integrates the resources in Table 1 . By means of such resources, SoBigData scientists have created VREs to deliver the so-called SoBigData exploratories : Explainable Machine Learning , Sports Data Science , Migration Studies , Societal Debates , Well-being & Economy , and City of Citizens . Each exploratory includes the resources required to perform Data science workflows in a controlled and shared environment. Resources range from data to methods, described more in detail in the following, together with their exploitation within the exploratories.

All the resources and instruments integrate into SoBigData RI are structured in such a way as to operate within the confines of the current data protection law with the focus on General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and ethical analysis of the fundamental values involved in social mining and AI. Each item into the catalogue has specific fields for managing ethical issues (e.g., if a dataset contains personal info) and fields for describing and managing intellectual properties.

4.1.2 Data resources: social mining and big data ecosystem

SoBigData RI defines policies supporting users in the collection, description, preservation, and sharing of their data sets. It implements data science making such data available for collaborative research by adopting various strategies, ranging from sharing the open data sets with the scientific community at large, to share the data with disclosure restriction allowing data access within secure environments.

Several big data sets are available through SoBigData RI including network graphs from mobile phone call data; networks crawled from many online social networks, including Facebook and Flickr, transaction micro-data from diverse retailers, query logs both from search engines and e-commerce, society-wide mobile phone call data records, GPS tracks from personal navigation devices, survey data about customer satisfaction or market research, extensive web archives, billions of tweets, and data from location-aware social networks.

4.1.3 Data science through SoBigData exploratories

Exploratories are thematic environments built on top of the SoBigData RI. An exploratory binds datasets with social mining methods providing the research context for supporting specific data science applications by: (i) providing the scientific context for performing the application. This context can be considered a container for binding specific methods, applications, services, and datasets; (ii) stimulating communities on the effectiveness of the analytical process related to the analysis, promoting scientific dissemination, result sharing, and reproducibility. The use of exploratories promotes the effectiveness of the data science trough research infrastructure services. The following sections report a short description of the six SoBigData exploratories. Figure 6 shows the main thematic areas covered by each exploratory. Due to its nature, Explainable Machine Learning exploratory can be applied to each sector where a black-box machine learning approach is used. The list of exploratories (and the data and methods inside them) are updated continuously and continue to grow over time. Footnote 9

SoBigData covers six thematic areas listed horizontally. Each exploratory covers more than one thematic area

City of citizens. This exploratory aims to collect data science applications and methods related to geo-referenced data. The latter describes the movements of citizens in a city, a territory, or an entire region. There are several studies and different methods that employ a wide variety of data sources to build models about the mobility of people and city characteristics in the scientific literature [ 30 , 32 ]. Like ecosystems, cities are open systems that live and develop utilizing flows of energy, matter, and information. What distinguishes a city from a colony is the human component (i.e., the process of transformation by cultural and technological evolution). Through this combination, cities are evolutionary systems that develop and co-evolve continuously with their inhabitants [ 24 ]. Cities are kaleidoscopes of information generated by a myriad of digital devices weaved into the urban fabric. The inclusion of tracking technologies in personal devices enabled the analysis of large sets of mobility data like GPS traces and call detail records.

Data science applied to human mobility is one of the critical topics investigated in SoBigData thanks to the decennial experience of partners in European projects. The study of human mobility led to the integration into the SoBigData of unique Global Positioning System (GPS) and call detail record (CDR) datasets of people and vehicle movements, and geo-referenced social network data as well as several mobility services: O/D (origin-destination) matrix computation, Urban Mobility Atlas Footnote 10 (a visual interface to city mobility patterns), GeoTopics Footnote 11 (for exploring patterns of urban activity from Foursquare), and predictive models: MyWay Footnote 12 (trajectory prediction), TripBuilder Footnote 13 (tourists to build personalized tours of a city). In human mobility, research questions come from geographers, urbanists, complexity scientists, data scientists, policymakers, and Big Data providers, as well as innovators aiming to provide applications for any service for the smart city ecosystem. The idea is to investigate the impact of political events on the well-being of citizens. This exploratory supports the development of “happiness” and “peace” indicators through text mining/opinion mining pipeline on repositories of online news. These indicators reveal that the level of crime of a territory can be well approximated by analyzing the news related to that territory. Generally, we study the impact of the economy on well-being and vice versa, e.g., also considering the propagation of shocks of financial distress in an economic or financial system crucially depends on the topology of the network interconnecting the different elements.

Well-being and economy. This exploratory tests the hypothesis that well-being is correlated to the business performance of companies. The idea is to combine statistical methods and traditional economic data (typically at low-frequency) with high-frequency data from non-traditional sources, such as, i.e., web, supermarkets, for now-casting economic, socioeconomic and well-being indicators. These indicators allow us to study and measure real-life costs by studying price variation and socioeconomic status inference. Furthermore, this activity supports studies on the correlation between people’s well-being and their social and mobility data. In this context, some basic hypothesis can be summarized as: (i) there are curves of age- and gender-based segregation distribution in boards of companies, which are characteristic to mean credit risk of companies in a region; (ii) low mean credit risk of companies in a region has a positive correlation to well-being; (iii) systemic risk correlates highly with well-being indices at a national level. The final aim is to provide a set of guidelines to national governments, methods, and indices for decision making on regulations affecting companies to improve well-being in the country, also considering effective policies to reduce operational risks such as credit risk, and external threats of companies [ 17 ].

Big Data, analyzed through the lenses of data science, provides means to understand our complex socioeconomic and financial systems. On the one hand, this offers new opportunities to measure the patterns of well-being and poverty at a local and global scale, empowering governments and policymakers with the unprecedented opportunity to nowcast relevant economic quantities and compare different countries, regions, and cities. On the other hand, this allows us to investigate the network underlying the complex systems of economy and finance, and it affects the aggregate output, the propagation of shocks or financial distress and systemic risk.

Societal debates. This exploratory employs data science approaches to answer research questions such as who is participating in public debates? What is the “big picture” response from citizens to a policy, election, referendum, or other political events? This kind of analysis allows scientists, policymakers, and citizens to understand the online discussion surrounding polarized debates [ 14 ]. The personal perception of online discussions on social media is often biased by the so-called filter bubble, in which automatic curation of content and relationships between users negatively affects the diversity of opinions available to them. Making a complete analysis of online polarized debates enables the citizens to be better informed and prepared for political outcomes. By analyzing content and conversations on social media and newspaper articles, data scientists study public debates and also assess public sentiment around debated topics, opinion diffusion dynamics, echo chambers formation and polarized discussions, fake news analysis, and propaganda bots. Misinformation is often the result of a distorted perception of concepts that, although unrelated, suddenly appear together in the same narrative. Understanding the details of this process at an early stage may help to prevent the birth and the diffusion of fake news. The misinformation fight includes the development of dynamical models of misinformation diffusion (possibly in contrast to the spread of mainstream news) as well as models of how attention cycles are accelerated and amplified by the infrastructures of online media.

Another important topic covered by this exploratory concerns the analysis of how social bots activity affects fake news diffusion. Determining whether a human or a bot controls a user account is a complex task. To the best of our knowledge, the only openly accessible solution to detect social bots is Botometer, an API that allows us to interact with an underlying machine learning system. Although Botometer has been proven to be entirely accurate in detecting social bots, it has limitations due to the Twitter API features: hence, an algorithm overcoming the barriers of current recipes is needed.

The resources related to Societal Debates exploratory, especially in the domain of media ecology and the fight against misinformation online, provide easy-to-use services to public bodies, media outlets, and social/political scientists. Furthermore, SoBigData supports new simulation models and experimental processes to validate in vivo the algorithms for fighting misinformation, curbing the pathological acceleration and amplification of online attention cycles, breaking the bubbles, and explore alternative media and information ecosystems.

Migration studies. Data science is also useful to understand the migration phenomenon. Knowledge about the number of immigrants living in a particular region is crucial to devise policies that maximize the benefits for both locals and immigrants. These numbers can vary rapidly in space and time, especially in periods of crisis such as wars or natural disasters.

This exploratory provides a set of data and tools for trying to answer some questions about migration flows. Through this exploratory, a data scientist studies economic models of migration and can observe how migrants choose their destination countries. A scientist can discover what is the meaning of “opportunities” that a country provides to migrants, and whether there are correlations between the number of incoming migrants and opportunities in the host countries [ 8 ]. Furthermore, this exploratory tries to understand how public perception of migration is changing using an opinion mining analysis. For example, social network analysis enables us to analyze the migrant’s social network and discover the structure of the social network for people who decided to start a new life in a different country [ 28 ].

Finally, we can also evaluate current integration indices based on official statistics and survey data, which can be complemented by Big Data sources. This exploratory aims to build combined integration indexes that take into account multiple data sources to evaluate integration on various levels. Such integration includes mobile phone data to understand patterns of communication between immigrants and natives; social network data to assess sentiment towards immigrants and immigration; professional network data (such as LinkedIn) to understand labor market integration, and local data to understand to what extent moving across borders is associated with a change in the cultural norms of the migrants. These indexes are fundamental to evaluate the overall social and economic effects of immigration. The new integration indexes can be applied with various space and time resolutions (small area methods) to obtain a complete image of integration, and complement official index.

Sports data science. The proliferation of new sensing technologies that provide high-fidelity data streams extracted from every game, is changing the way scientists, fans and practitioners conceive sports performance. The combination of these (big) data with the tools of data science provides the possibility to unveil complex models underlying sports performance and enables to perform many challenging tasks: from automatic tactical analysis to data-driven performance ranking; game outcome prediction, and injury forecasting. The idea is to foster research on sports data science in several directions. The application of explainable AI and deep learning techniques can be hugely beneficial to sports data science. For example, by using adversarial learning, we can modify the training plans of players that are associated with high injury risk and develop training plans that maximize the fitness of players (minimizing their injury risk). The use of gaming, simulation, and modeling is another set of tools that can be used by coaching staff to test tactics that can be employed against a competitor. Furthermore, by using deep learning on time series, we can forecast the evolution of the performance of players and search for young talents.

This exploratory examines the factors influencing sports success and how to build simulation tools for boosting both individual and collective performance. Furthermore, this exploratory describes performances employing data, statistics, and models, allowing coaches, fans, and practitioners to understand (and boost) sports performance [ 42 ].

Explainable machine learning. Artificial Intelligence, increasingly based on Big Data analytics, is a disruptive technology of our times. This exploratory provides a forum for studying effects of AI on the future society. In this context, SoBigData studies the future of labor and the workforce, also through data- and model-driven analysis, simulations, and the development of methods that construct human understandable explanations of AI black-box models [ 20 ].

Black box systems for automated decision making map a user’s features into a class that predicts the behavioral traits of individuals, such as credit risk, health status, without exposing the reasons why. Most of the time, the internal reasoning of these algorithms is obscure even to their developers. For this reason, the last decade has witnessed the rise of a black box society. This exploratory is developing a set of techniques and tools which allow data analysts to understand why an algorithm produce a decision. These approaches are designed not for discovering a lack of transparency but also for discovering possible biases inherited by the algorithms from human prejudices and artefacts hidden in the training data (which may lead to unfair or wrong decisions) [ 35 ].

5 Conclusions: individual and collective intelligence

The world’s technological per-capita capacity to store information has roughly doubled every 40 months since the 1980s [ 23 ]. Since 2012, every day 2.5 exabytes (2.5 \(\times \) 10 \(^18\) bytes) of data were created; as of 2014, every day 2.3 zettabytes (2.3 \(\times \) 10 \(^21\) bytes) of data were generated by Super-power high-tech Corporation worldwide. Soon zettabytes of useful public and private data will be widely and openly available. In the next years, smart applications such as smart grids, smart logistics, smart factories, and smart cities will be widely deployed across the continent and beyond. Ubiquitous broadband access, mobile technology, social media, services, and internet of think on billions of devices will have contributed to the explosion of generated data to a total global estimate of 40 zettabytes.

In this work, we have introduced data science as a new challenge and opportunity for the next years. In this context, we have tried to summarize in a concise way several aspects related to data science applications and their impacts on society, considering both the new services available and the new job perspectives. We have also introduced issues in managing data representing human behavior and showed how difficult it is to preserve personal information and privacy. With the introduction of SoBigData RI and exploratories, we have provided virtual environments where it is possible to understand the potentiality of data science in different research contexts.

Concluding, we can state that social dilemmas occur when there is a conflict between the individual and public interest. Such problems also appear in the ecosystem of distributed AI systems (based on data science tools) and humans, with additional difficulties due: on the one hand, to the relative rigidity of the trained AI systems and the necessity of achieving social benefit, and, on the other hand, to the necessity of keeping individuals interested. What are the principles and solutions for individual versus social optimization using AI, and how can an optimum balance be achieved? The answer is still open, but these complex systems have to work on fulfilling collective goals, and requirements, with the challenge that human needs change over time and move from one context to another. Every AI system should operate within an ethical and social framework in understandable, verifiable, and justifiable way. Such systems must, in any case, work within the bounds of the rule of law, incorporating protection of fundamental rights into the AI infrastructure. In other words, the challenge is to develop mechanisms that will result in the system converging to an equilibrium that complies with European values and social objectives (e.g., social inclusion) but without unnecessary losses of efficiency.

Interestingly, data science can play a vital role in enhancing desirable behaviors in the system, e.g., by supporting coordination and cooperation that is, more often than not, crucial to achieving any meaningful improvements. Our ultimate goal is to build the blueprint of a sociotechnical system in which AI not only cooperates with humans but, if necessary, helps them to learn how to collaborate, as well as other desirable behaviors. In this context, it is also essential to understand how to achieve robustness of the human and AI ecosystems in respect of various types of malicious behaviors, such as abuse of power and exploitation of AI technical weaknesses.

We conclude by paraphrasing Stephen Hawking in his Brief Answers to the Big Questions: the availability of data on its own will not take humanity to the future, but its intelligent and creative use will.

http://www.sdss3.org/collaboration/ .

e.g., https://www.nature.com/sdata/policies/repositories .

Responsible Data Science program: https://redasci.org/ .

https://emergency.copernicus.eu/ .

Nowcasting in economics is the prediction of the present, the very near future, and the very recent past state of an economic indicator.

https://www.unglobalpulse.org/ .

http://sobigdata.eu .

https://www.gcube-system.org/ .

https://sobigdata.d4science.org/catalogue-sobigdata .

http://www.sobigdata.eu/content/urban-mobility-atlas .

http://data.d4science.org/ctlg/ResourceCatalogue/geotopics_-_a_method_and_system_to_explore_urban_activity .

http://data.d4science.org/ctlg/ResourceCatalogue/myway_-_trajectory_prediction .

http://data.d4science.org/ctlg/ResourceCatalogue/tripbuilder .

Abitbol, J.L., Fleury, E., Karsai, M.: Optimal proxy selection for socioeconomic status inference on twitter. Complexity 2019 , 60596731–605967315 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/6059673

Article Google Scholar

Amato, G., Candela, L., Castelli, D., Esuli, A., Falchi, F., Gennaro, C., Giannotti, F., Monreale, A., Nanni, M., Pagano, P., Pappalardo, L., Pedreschi, D., Pratesi, F., Rabitti, F., Rinzivillo, S., Rossetti, G., Ruggieri, S., Sebastiani, F., Tesconi, M.: How data mining and machine learning evolved from relational data base to data science. In: Flesca, S., Greco, S., Masciari, E., Saccà, D. (eds.) A Comprehensive Guide Through the Italian Database Research Over the Last 25 Years, Studies in Big Data, vol. 31, pp. 287–306. Springer, Berlin (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-61893-7_17

Chapter Google Scholar

Andrienko, G.L., Andrienko, N.V., Budziak, G., Dykes, J., Fuchs, G., von Landesberger, T., Weber, H.: Visual analysis of pressure in football. Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 31 (6), 1793–1839 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10618-017-0513-2

Article MathSciNet Google Scholar

Assante, M., Candela, L., Castelli, D., Cirillo, R., Coro, G., Frosini, L., Lelii, L., Mangiacrapa, F., Marioli, V., Pagano, P., Panichi, G., Perciante, C., Sinibaldi, F.: The gcube system: delivering virtual research environments as-a-service. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 95 , 445–453 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.future.2018.10.035

Assante, M., Candela, L., Castelli, D., Cirillo, R., Coro, G., Frosini, L., Lelii, L., Mangiacrapa, F., Pagano, P., Panichi, G., Sinibaldi, F.: Enacting open science by d4science. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.future.2019.05.063

Barabasi, A.L., Gulbahce, N., Loscalzo, J.: Network medicine: a network-based approach to human disease. Nature reviews. Genetics 12 , 56–68 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg2918

Candela, L., Castelli, D., Pagano, P.: Virtual research environments: an overview and a research agenda. Data Sci. J. 12 , GRDI75–GRDI81 (2013). https://doi.org/10.2481/dsj.GRDI-013

Coletto, M., Esuli, A., Lucchese, C., Muntean, C.I., Nardini, F.M., Perego, R., Renso, C.: Sentiment-enhanced multidimensional analysis of online social networks: perception of the mediterranean refugees crisis. In: Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE/ACM International Conference on Advances in Social Networks Analysis and Mining, ASONAM’16, pp. 1270–1277. IEEE Press, Piscataway, NJ, USA (2016). http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=3192424.3192657

Coscia, M., Rossetti, G., Giannotti, F., Pedreschi, D.: Uncovering hierarchical and overlapping communities with a local-first approach. TKDD 9 (1), 6:1–6:27 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1145/2629511

Cresci, S., Minutoli, S., Nizzoli, L., Tardelli, S., Tesconi, M.: Enriching digital libraries with crowdsensed data. In: P. Manghi, L. Candela, G. Silvello (eds.) Digital Libraries: Supporting Open Science—15th Italian Research Conference on Digital Libraries, IRCDL 2019, Pisa, Italy, 31 Jan–1 Feb 2019, Proceedings, Communications in Computer and Information Science, vol. 988, pp. 144–158. Springer (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-11226-4_12

Cresci, S., Petrocchi, M., Spognardi, A., Tognazzi, S.: Better safe than sorry: an adversarial approach to improve social bot detection. In: P. Boldi, B.F. Welles, K. Kinder-Kurlanda, C. Wilson, I. Peters, W.M. Jr. (eds.) Proceedings of the 11th ACM Conference on Web Science, WebSci 2019, Boston, MA, USA, June 30–July 03, 2019, pp. 47–56. ACM (2019). https://doi.org/10.1145/3292522.3326030

Cresci, S., Pietro, R.D., Petrocchi, M., Spognardi, A., Tesconi, M.: Social fingerprinting: detection of spambot groups through dna-inspired behavioral modeling. IEEE Trans. Dependable Sec. Comput. 15 (4), 561–576 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1109/TDSC.2017.2681672

Furletti, B., Trasarti, R., Cintia, P., Gabrielli, L.: Discovering and understanding city events with big data: the case of rome. Information 8 (3), 74 (2017). https://doi.org/10.3390/info8030074

Garimella, K., De Francisci Morales, G., Gionis, A., Mathioudakis, M.: Reducing controversy by connecting opposing views. In: Proceedings of the 10th ACM International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining, WSDM’17, pp. 81–90. ACM, New York, NY, USA (2017). https://doi.org/10.1145/3018661.3018703

Giannotti, F., Trasarti, R., Bontcheva, K., Grossi, V.: Sobigdata: social mining & big data ecosystem. In: P. Champin, F.L. Gandon, M. Lalmas, P.G. Ipeirotis (eds.) Companion of the The Web Conference 2018 on The Web Conference 2018, WWW 2018, Lyon , France, April 23–27, 2018, pp. 437–438. ACM (2018). https://doi.org/10.1145/3184558.3186205

Grossi, V., Rapisarda, B., Giannotti, F., Pedreschi, D.: Data science at sobigdata: the european research infrastructure for social mining and big data analytics. I. J. Data Sci. Anal. 6 (3), 205–216 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41060-018-0126-x

Grossi, V., Romei, A., Ruggieri, S.: A case study in sequential pattern mining for it-operational risk. In: W. Daelemans, B. Goethals, K. Morik (eds.) Machine Learning and Knowledge Discovery in Databases, European Conference, ECML/PKDD 2008, Antwerp, Belgium, 15–19 Sept 2008, Proceedings, Part I, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol. 5211, pp. 424–439. Springer (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-87479-9_46

Guidotti, R., Coscia, M., Pedreschi, D., Pennacchioli, D.: Going beyond GDP to nowcast well-being using retail market data. In: A. Wierzbicki, U. Brandes, F. Schweitzer, D. Pedreschi (eds.) Advances in Network Science—12th International Conference and School, NetSci-X 2016, Wroclaw, Poland, 11–13 Jan 2016, Proceedings, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol. 9564, pp. 29–42. Springer (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-28361-6_3

Guidotti, R., Monreale, A., Nanni, M., Giannotti, F., Pedreschi, D.: Clustering individual transactional data for masses of users. In: Proceedings of the 23rd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Halifax, NS, Canada, 13–17 Aug 2017, pp. 195–204. ACM (2017). https://doi.org/10.1145/3097983.3098034

Guidotti, R., Monreale, A., Ruggieri, S., Turini, F., Giannotti, F., Pedreschi, D.: A survey of methods for explaining black box models. ACM Comput. Surv. 51 (5), 93:1–93:42 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1145/3236009

Guidotti, R., Monreale, A., Turini, F., Pedreschi, D., Giannotti, F.: A survey of methods for explaining black box models. CoRR abs/1802.01933 (2018). arxiv: 1802.01933

Guidotti, R., Nanni, M., Rinzivillo, S., Pedreschi, D., Giannotti, F.: Never drive alone: boosting carpooling with network analysis. Inf. Syst. 64 , 237–257 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.is.2016.03.006

Hilbert, M., Lopez, P.: The world’s technological capacity to store, communicate, and compute information. Science 332 (6025), 60–65 (2011)

Kennedy, C.A., Stewart, I., Facchini, A., Cersosimo, I., Mele, R., Chen, B., Uda, M., Kansal, A., Chiu, A., Kim, K.g., Dubeux, C., Lebre La Rovere, E., Cunha, B., Pincetl, S., Keirstead, J., Barles, S., Pusaka, S., Gunawan, J., Adegbile, M., Nazariha, M., Hoque, S., Marcotullio, P.J., González Otharán, F., Genena, T., Ibrahim, N., Farooqui, R., Cervantes, G., Sahin, A.D., : Energy and material flows of megacities. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 112 (19), 5985–5990 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1504315112

Korjani, S., Damiano, A., Mureddu, M., Facchini, A., Caldarelli, G.: Optimal positioning of storage systems in microgrids based on complex networks centrality measures. Sci. Rep. (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-35128-6

Lorini, V., Castillo, C., Dottori, F., Kalas, M., Nappo, D., Salamon, P.: Integrating social media into a pan-european flood awareness system: a multilingual approach. In: Z. Franco, J.J. González, J.H. Canós (eds.) Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Information Systems for Crisis Response and Management, València, Spain, 19–22 May 2019. ISCRAM Association (2019). http://idl.iscram.org/files/valeriolorini/2019/1854-_ValerioLorini_etal2019.pdf

Lulli, A., Gabrielli, L., Dazzi, P., Dell’Amico, M., Michiardi, P., Nanni, M., Ricci, L.: Scalable and flexible clustering solutions for mobile phone-based population indicators. Int. J. Data Sci. Anal. 4 (4), 285–299 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41060-017-0065-y

Moise, I., Gaere, E., Merz, R., Koch, S., Pournaras, E.: Tracking language mobility in the twitter landscape. In: C. Domeniconi, F. Gullo, F. Bonchi, J. Domingo-Ferrer, R.A. Baeza-Yates, Z. Zhou, X. Wu (eds.) IEEE International Conference on Data Mining Workshops, ICDM Workshops 2016, 12–15 Dec 2016, Barcelona, Spain., pp. 663–670. IEEE Computer Society (2016). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICDMW.2016.0099

Nanni, M.: Advancements in mobility data analysis. In: F. Leuzzi, S. Ferilli (eds.) Traffic Mining Applied to Police Activities—Proceedings of the 1st Italian Conference for the Traffic Police (TRAP-2017), Rome, Italy, 25–26 Oct 2017, Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing, vol. 728, pp. 11–16. Springer (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-75608-0_2

Nanni, M., Trasarti, R., Monreale, A., Grossi, V., Pedreschi, D.: Driving profiles computation and monitoring for car insurance crm. ACM Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol. 8 (1), 14:1–14:26 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1145/2912148

Pappalardo, G., di Matteo, T., Caldarelli, G., Aste, T.: Blockchain inefficiency in the bitcoin peers network. EPJ Data Sci. 7 (1), 30 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1140/epjds/s13688-018-0159-3

Pappalardo, L., Barlacchi, G., Pellungrini, R., Simini, F.: Human mobility from theory to practice: Data, models and applications. In: S. Amer-Yahia, M. Mahdian, A. Goel, G. Houben, K. Lerman, J.J. McAuley, R.A. Baeza-Yates, L. Zia (eds.) Companion of The 2019 World Wide Web Conference, WWW 2019, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 May 2019., pp. 1311–1312. ACM (2019). https://doi.org/10.1145/3308560.3320099

Pappalardo, L., Cintia, P., Ferragina, P., Massucco, E., Pedreschi, D., Giannotti, F.: Playerank: data-driven performance evaluation and player ranking in soccer via a machine learning approach. ACM TIST 10 (5), 59:1–59:27 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1145/3343172

Pappalardo, L., Vanhoof, M., Gabrielli, L., Smoreda, Z., Pedreschi, D., Giannotti, F.: An analytical framework to nowcast well-being using mobile phone data. CoRR abs/1606.06279 (2016). arxiv: 1606.06279

Pasquale, F.: The Black Box Society: The Secret Algorithms That Control Money and Information. Harvard University Press, Cambridge (2015)

Book Google Scholar

Piškorec, M., Antulov-Fantulin, N., Miholić, I., Šmuc, T., Šikić, M.: Modeling peer and external influence in online social networks: Case of 2013 referendum in croatia. In: Cherifi, C., Cherifi, H., Karsai, M., Musolesi, M. (eds.) Complex Networks & Their Applications VI. Springer, Cham (2018)

Google Scholar

Ranco, G., Aleksovski, D., Caldarelli, G., Mozetic, I.: Investigating the relations between twitter sentiment and stock prices. CoRR abs/1506.02431 (2015). arxiv: 1506.02431

Ribeiro, M.T., Singh, S., Guestrin, C.: “why should I trust you?”: Explaining the predictions of any classifier. In: B. Krishnapuram, M. Shah, A.J. Smola, C.C. Aggarwal, D. Shen, R. Rastogi (eds.) Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 Aug 2016, pp. 1135–1144. ACM (2016). https://doi.org/10.1145/2939672.2939778

Ribeiro, M.T., Singh, S., Guestrin, C.: Anchors: High-precision model-agnostic explanations. In: S.A. McIlraith, K.Q. Weinberger (eds.) Proceedings of the Thirty-Second AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, (AAAI-18), the 30th innovative Applications of Artificial Intelligence (IAAI-18), and the 8th AAAI Symposium on Educational Advances in Artificial Intelligence (EAAI-18), New Orleans, Louisiana, USA, 2–7 Feb 2018, pp. 1527–1535. AAAI Press (2018). https://www.aaai.org/ocs/index.php/AAAI/AAAI18/-paper/view/16982

Rossetti, G., Milli, L., Rinzivillo, S., Sîrbu, A., Pedreschi, D., Giannotti, F.: Ndlib: a python library to model and analyze diffusion processes over complex networks. Int. J. Data Sci. Anal. 5 (1), 61–79 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41060-017-0086-6

Rossetti, G., Pappalardo, L., Pedreschi, D., Giannotti, F.: Tiles: an online algorithm for community discovery in dynamic social networks. Mach. Learn. 106 (8), 1213–1241 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10994-016-5582-8

Rossi, A., Pappalardo, L., Cintia, P., Fernández, J., Iaia, M.F., Medina, D.: Who is going to get hurt? predicting injuries in professional soccer. In: J. Davis, M. Kaytoue, A. Zimmermann (eds.) Proceedings of the 4th Workshop on Machine Learning and Data Mining for Sports Analytics co-located with 2017 European Conference on Machine Learning and Principles and Practice of Knowledge Discovery in Databases (ECML PKDD 2017), Skopje, Macedonia, 18 Sept 2017., CEUR Workshop Proceedings, vol. 1971, pp. 21–30. CEUR-WS.org (2017). http://ceur-ws.org/Vol-1971/paper-04.pdf

Ruggieri, S., Pedreschi, D., Turini, F.: DCUBE: discrimination discovery in databases. In: A.K. Elmagarmid, D. Agrawal (eds.) Proceedings of the ACM SIGMOD International Conference on Management of Data, SIGMOD 2010, Indianapolis, Indiana, USA, 6–10 June 2010, pp. 1127–1130. ACM (2010). https://doi.org/10.1145/1807167.1807298

Simonyan, K., Vedaldi, A., Zisserman, A.: Deep inside convolutional networks: Visualising image classification models and saliency maps. CoRR abs/1312.6034 (2013). http://dblp.uni-trier.de/db/journals/corr/corr1312.html#SimonyanVZ13

Smilkov, D., Thorat, N., Kim, B., Viégas, F.B., Wattenberg, M.: Smoothgrad: removing noise by adding noise. CoRR abs/1706.03825 (2017). arxiv: 1706.03825

Sundararajan, M., Taly, A., Yan, Q.: Axiomatic attribution for deep networks. In: D. Precup, Y.W. Teh (eds.) Proceedings of the 34th International Conference on Machine Learning, Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, vol. 70, pp. 3319–3328. PMLR, International Convention Centre, Sydney, Australia (2017). http://proceedings.mlr.press/v70/sundararajan17a.html

Trasarti, R., Guidotti, R., Monreale, A., Giannotti, F.: Myway: location prediction via mobility profiling. Inf. Syst. 64 , 350–367 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.is.2015.11.002

Traub, J., Quiané-Ruiz, J., Kaoudi, Z., Markl, V.: Agora: Towards an open ecosystem for democratizing data science & artificial intelligence. CoRR abs/1909.03026 (2019). arxiv: 1909.03026

Vazifeh, M.M., Zhang, H., Santi, P., Ratti, C.: Optimizing the deployment of electric vehicle charging stations using pervasive mobility data. Transp Res A Policy Practice 121 (C), 75–91 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2019.01.002

Vermeulen, A.F.: Practical Data Science: A Guide to Building the Technology Stack for Turning Data Lakes into Business Assets, 1st edn. Apress, New York (2018)

Download references

Acknowledgements