Research Professor

Key skills:

- A Higher Degree ( PhD / DPhil / MD ) with substantial postdoctoral research experience in a relevant specialist subject area

- Passion for innovative and original research, and active contribution to the advancement of knowledge at a national and international level

- Distinguished record of research with a reputation for international excellence

- Able to attract and secure research grants and funding

- Experience leading and managing research projects

- Able to demonstrate excellent networking, collaboration and communication skills, including the ability to work successfully in an international setting.

Typical job titles: Research Professor, Professor, Full Professor, Chair

'Professor' is possibly the most well-known university job title, and the most senior role in the research pathway. The key part of the role is to lead research. A Research Professor must lead and maintain their own research activities and acquire external funding for new research. In almost all cases they will either lead a team, or different teams working on different research projects.

Being a successful research leader will enhance your reputation, will like increase your salary, as well as the prestige of the university where the position is based. Many Professors make a significant contribution to their subject field .

A Professor is also expected to take on managerial responsibilities, taking part in strategic planning and decision-making in their department.

Jo Shien Ng

Jo Shien Ng moved from Malaysia to the UK in 1997 to complete her degree in electronic engineering. She has risen through the ranks to become Professor of Semiconductor Devices at University of Sheffield despite, she says, self-doubt that nearly prevented her pursuing a research career.

The earlier you can get to grips with the landscape and requirements of STEM careers, the better.

- Career Advice

- Advancing in the Faculty

25 Rules for Successful Research Professors

Richard Primack offers advice for how to be a happy, healthy and productive researcher year after year.

By Richard Primack

You have / 5 articles left. Sign up for a free account or log in.

Yutthana Gaetgeaw/Istock/Getty Images Plus

As a contented and productive senior professor at a major research university, colleagues and students often ask me for advice. They wonder about achieving work-life balance, interacting with students, navigating administrative challenges, writing papers and grant proposals, and many other topics. Out of those conversations, I have developed my own “rules of conduct”—guidelines that have contributed to my academic longevity, successes, and satisfaction during my 45-year career.

Although other academics have published general guidance for professo rs and rules for effective teaching , comparatively few have written about how to be a productive and fulfilled research professor. The requirements for research professors are different than for teaching faculty members: researchers tend to spend more hours working on manuscripts and grant proposals or engaging with group members on research projects, and less time developing curricula and lessons or teaching students in classroom settings.

What follows are the primary rules I’ve written out at the behest of colleagues just starting their careers who want copies for their own reference. I’ve broken them down into major categories, starting with health and overall well-being. I recognize that some of these rules reflect my particular discipline and experiences, but I believe most of them are widely applicable.

Health and Overall Well-Being

- Spend time doing what you love; it will help prevent burnout. I am a botanist and love plants, so from March to October I spend time outside every day studying and enjoying plants. During the winter, I spend more time attending seminars, reading the scientific literature, and writing articles about plants. Keeping in touch with what you value can help sustain you over the long haul of your career.

- Work to stay strong, healthy and content. Devote time to activities that maintain and improve your physical and mental health, clear your thinking after hours on the computer, and boost your creativity—all of which can improve your research efforts. Depending on your interests and needs, those activities might involve exercise, hobbies, spending time with family and friends, and religious observances, among others.

- Recognize that no job is ideal. You are at your current job because it was the best you could get at the time. So, unless you are serious about looking for another position, make the best of where you are, do a good job and identify ways you can make your institution stronger. Don’t be envious of colleagues at more prestigious or wealthier universities; money and prestige don’t correlate with happiness.

- Determine your own worth as a professor and a person. Base that assessment on your own personal measures of success—such as satisfaction with your work, positive feedback from students and colleagues, the production of good research, and the achievement of a reasonable work-life balance. That said, if you want to want to receive promotions and salary raises, you do need to also pay close attention to the expectations of your university.

- Learn how to effectively apply for grants. A key first step in almost any application process is to obtain copies of recent successful grant proposals or fellowship applications. You can typically write to recent awardees to get these copies. Successful proposals or applications are extremely useful as guides for developing the content, style and organization of your document.

- Continually broaden your scope. Learn new skills and research content that can maintain your enthusiasm. Use sabbatical leaves and time off in the summer to do so. Alternatively, rather than spending time learning a new discipline yourself, find an expert in a key field necessary for your research and make them your collaborator and friend.

- Pay someone (or offer co-authorship) to help with routine tasks. Those might include creating figures, editing manuscripts, formatting bibliographies, and performing statistical tests. That will leave you more time for the creative parts of research.

- Be willing to review papers for journals and proposals for funding agencies. They are the best sources of information on advances in your research area. Be willing to read over and comment on colleagues’ manuscripts and proposals. That is helpful to them, and you will learn more about current ideas in the field.

Working With Grad Students and Junior Colleagues

- Help graduate students and undergrads publish papers in peer-reviewed journals. You might need to extensively edit or rewrite a paper, but this will help the students in their scientific development as well as advance the academic discipline.

- Work closely with first-year graduate students on a few carefully selected endeavors. See what they like to do. As the students mature as scientists, encourage them to develop their own projects and articles.

- Be fair, generous, and transparent with authorship on publications. Be especially so on projects involving junior colleagues, graduate students and undergrads. It is the right thing to do, and it may help start their careers in research . If your grad student or colleague has done anything close to half of the project work, let them be first author of the resulting publication, as they very likely have greater need for the recognition.

Editors' Picks

- Black, Hispanic Faculty Far Less Likely to Get ‘Gold Standard’ Tenure Recommendations

- Stress Testing the FAFSA

- Employers Say Students Need AI Skills. What If Students Don’t Want Them?

Students and Teaching

- When you teach, follow “The Golden Rule of being a professor.” Treat students the way you would like professors to treat someone in your family or how you wish you had been treated when you were a student.

- Use your research to strengthen your teaching, and use your teaching to explore new research ideas. This is particularly appropriate in advanced courses and seminars—which, in rare situations, might even produce publishable review papers as group projects by the end of the semester.

- Read and review student work within a reasonable period of time. Normally, that should be within one or two weeks. While a thorough reading is best, a fast read with a few general comments is better than not reading a paper at all.

- Get to know students and other members of your research group as people. Show them respect and sympathy. Meet regularly with your students so you are aware of their progress, life circumstances and problems. That will help you develop actions to help their progress.

Collegial Relationships

- Nominate students and colleagues for awards and fellowships. Focus especially on junior colleagues at your university and colleagues at other universities. It creates good will, and they may win.

- Ask your colleagues to nominate you for awards and fellowships. It’s perfectly acceptable—this is the way the world works—and those nominations can help your career. Many colleagues will be happy to do this, but they might not think of it on their own.

- Keep in regular touch with colleagues. And by that, I mean broadly—in your department, other departments, the university administration, and at other institutions. Spend time talking with colleagues, especially junior faculty. Invite people for coffee or lunch. Exchange emails or organize a Zoom call with a distant colleague. You may develop long-term friendships, help colleagues with advice and discover surprising and useful information. Inviting researchers from other universities to visit your institution to present a talk is another great way to establish and deepen relationships.

Outside Relationships

- Get out and about. Attend seminars at other universities and in departments at your institution as well as society meetings when possible. This is a valuable way to grow your research network, hear about academic exchanges and funding opportunities, and gain new information and insights. Send follow-up emails to people with whom you had a good talk or who gave a good presentation.

- Help colleagues from foreign countries improve their English writing in drafts of their papers. Alternatively, match them up with freelance editors . When needed, and if you have the means, consider paying for this editing out of some discretionary funding source. Your foreign colleagues will truly appreciate the gesture.

- Agree to write recommendation letters for students. Also write letters of promotion for colleagues at other universities. If you are busy, a short clear definitive letter is fine. This is part of being a responsible and caring citizen of the academic community.

The Wider Audience

- Make your research available to a broad audience. You can publish popular versions of your academic articles, write blog posts and press releases, contact and talk with journalists, produce or be interviewed for podcasts, or become active on social media like X or LinkedIn. Make sure to let your university’s public relations office know about these efforts, ideally before they occur, to get the broadest exposure and engagement.

- Update your website at least once a year. If you have a blog or something similar, post regularly. Send PDFs of your recent academic papers to your research colleagues to ensure that your work is read by the target audience.

Talks and Travel

- When visiting another university, ask to meet with graduate students and others at early stages of their careers. If possible, treat them for dinner or lunch. They will often remember this experience for decades.

- When you give talks or seminars, try to arrive 10 to 15 minutes early. That way, you can chat with audience members and find out who they are, their backgrounds, and (for foreign audiences) their level of English comprehension. Adjust your lecture, as needed, with this new information in mind to best speak to this particular audience.

To conclude, other scholars may have developed additional rules, and I invite them to share them with me and their own colleagues. Meanwhile, I hope those I’ve outlined will help you on your career journey. If 25 rules seem like too many, just select a few that might be useful. Good luck!

Richard Primack is a professor of biology at Boston University. He has served as the editor-in-chief of Biological Conservation and president of the Association for Tropical Biology and Conservation, and has authored the popular book Walden Warming: Climate Change Comes to Thoreau’s Woods as well as several conservation biology textbooks .

Kicking Off the School Year With a Campus-Wide Event

The University of Tennessee, Knoxville created a back-to-school celebration for the entire university community and t

Share This Article

More from advancing in the faculty.

A Timetable for Navigating Your Tenure Journey

Ruth Monnier and Mark M.

Why Grad Schools Should Make the Case for Public Scholarship

Making the Most of Individual Development Plans

They can be used for promoting communication, collaboration and growth within research groups, write Jacob J.

- Become a Member

- Sign up for Newsletters

- Learning & Assessment

- Diversity & Equity

- Career Development

- Labor & Unionization

- Shared Governance

- Academic Freedom

- Books & Publishing

- Financial Aid

- Residential Life

- Free Speech

- Physical & Mental Health

- Race & Ethnicity

- Sex & Gender

- Socioeconomics

- Traditional-Age

- Adult & Post-Traditional

- Teaching & Learning

- Artificial Intelligence

- Digital Publishing

- Data Analytics

- Administrative Tech

- Alternative Credentials

- Financial Health

- Cost-Cutting

- Revenue Strategies

- Academic Programs

- Physical Campuses

- Mergers & Collaboration

- Fundraising

- Research Universities

- Regional Public Universities

- Community Colleges

- Private Nonprofit Colleges

- Minority-Serving Institutions

- Religious Colleges

- Women's Colleges

- Specialized Colleges

- For-Profit Colleges

- Executive Leadership

- Trustees & Regents

- State Oversight

- Accreditation

- Politics & Elections

- Supreme Court

- Student Aid Policy

- Science & Research Policy

- State Policy

- Colleges & Localities

- Employee Satisfaction

- Remote & Flexible Work

- Staff Issues

- Study Abroad

- International Students in U.S.

- U.S. Colleges in the World

- Intellectual Affairs

- Seeking a Faculty Job

- Seeking an Administrative Job

- Advancing as an Administrator

- Beyond Transfer

- Call to Action

- Confessions of a Community College Dean

- Higher Ed Gamma

- Higher Ed Policy

- Just Explain It to Me!

- Just Visiting

- Law, Policy—and IT?

- Leadership & StratEDgy

- Leadership in Higher Education

- Learning Innovation

- Online: Trending Now

- Resident Scholar

- University of Venus

- Student Voice

- Academic Life

- Health & Wellness

- The College Experience

- Life After College

- Academic Minute

- Weekly Wisdom

- Reports & Data

- Quick Takes

- Advertising & Marketing

- Consulting Services

- Data & Insights

- Hiring & Jobs

- Event Partnerships

4 /5 Articles remaining this month.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

- Sign Up, It’s FREE

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience.

Research & Faculty

You are in a modal window. Press the escape key to exit.

- News & Events

- See programs

Common Searches

- Why is it called Johns Hopkins?

- What majors and minors are offered?

- Where can I find information about graduate programs?

- How much is tuition?

- What financial aid packages are available?

- How do I apply?

- How do I get to campus?

- Where can I find job listings?

- Where can I log in to myJHU?

- Where can I log in to SIS?

- University Leadership

- History & Mission

- Diversity & Inclusion

- Notable Alumni

- Hopkins in the Community

- Hopkins in D.C.

- Hopkins Around the World

- News from Johns Hopkins

- Undergraduate Studies

- Graduate Studies

- Online Studies

- Part-Time & Non-Degree Programs

- Summer Programs

- Academic Calendars

- Advanced International Studies

- Applied Physics Laboratory

- Arts & Sciences

- Engineering

- Peabody Conservatory

- Public Health

- Undergraduate Admissions

- Graduate Admissions

- Plan a Visit

- Tuition & Costs

- Financial Aid

- Innovation & Incubation

- Bloomberg Distinguished Professors

- Undergraduate Research

- Our Campuses

- About Baltimore

- Housing & Dining

- Arts & Culture

- Health & Wellness

- Disability Services

- Calendar of Events

- Maps & Directions

- Contact the University

- Employment Opportunities

- Give to the University

- For Parents

- For News Media

- Office of the President

- Office of the Provost

- Gilman’s Inaugural Address

- Academic Support

- Study Abroad

- Nobel Prize winners

- Homewood Campus

- Emergency Contact Information

We are America’s first research university , founded on the principle that by pursuing big ideas and sharing what we learn, we can make the world a better place. For more than 140 years, our faculty and students have worked side by side in pursuit of discoveries that improve lives.

What kinds of discoveries? We made water purification possible, launched the field of genetic engineering, and authenticated the Dead Sea Scrolls. We invented saccharine, CPR, and the supersonic ramjet engine. Our efforts have resulted in child safety restraint laws; the creation of Dramamine, Mercurochrome, and rubber surgical gloves; and the development of a revolutionary surgical procedure to correct heart defects in infants.

The research opportunities here are just endless. That’s really what I was looking for, a place where it’s very easy to do research .

Researchers at our nine academic divisions and at the university’s Applied Physics Laboratory have made us the nation’s leader in federal research and development funding each year since 1979. Those same researchers mentor our inquisitive students—about two-thirds of our undergrads engage in some form of research during their time here.

Research isn’t just something we do—it’s who we are. Every day, our faculty and students work side by side in a tireless pursuit of discovery, continuing our founding mission to bring knowledge to the world.

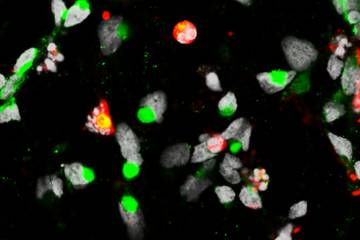

Zika’s impact on early brain development

Johns Hopkins researchers contribute to breakthrough study showing likely biological link between Zika virus and microcephaly, a birth defect linked to abnormally small head size and stunted brain development in newborns.

- Johns Hopkins University

- Address Baltimore, Maryland

- Phone number 410-516-8000

- © 2024 Johns Hopkins University. All rights reserved.

- Schools & Divisions

- Admissions & Aid

- Research & Faculty

- Campus Life

- University Policies and Statements

- Privacy Statement

- Title IX Information and Resources

- Higher Education Act Disclosures

- Clery Disclosure

- Accessibility

Explore Jobs

- Jobs Near Me

- Remote Jobs

- Full Time Jobs

- Part Time Jobs

- Entry Level Jobs

- Work From Home Jobs

Find Specific Jobs

- $15 Per Hour Jobs

- $20 Per Hour Jobs

- Hiring Immediately Jobs

- High School Jobs

- H1b Visa Jobs

Explore Careers

- Business And Financial

- Architecture And Engineering

- Computer And Mathematical

Explore Professions

What They Do

- Certifications

- Demographics

Best Companies

- Health Care

- Fortune 500

Explore Companies

- CEO And Executies

- Resume Builder

- Career Advice

- Explore Majors

- Questions And Answers

- Interview Questions

What does a Research Professor do?

Research professors lead the research culture in their departments. In some cases, they will do less undergraduate teaching and focus more on teaching post-graduates. They also teach students at higher education institutions. They focus on their research activities that include presenting research findings at conferences worldwide. They are involved in initiatives working with private sectors and other public sector bodies. Part of their duties includes marking assessed work, attending planning meetings to ensure cross-departmental parity, and doing administrative tasks within the department.

- Responsibilities

- Skills And Traits

- Comparisions

- Types of Research Professor

Research professor responsibilities

As a research professor, one's responsibilities revolve around conducting and supervising research, as well as teaching. According to Phillis Sheppard Ph.D. , E. Rhodes and Leona B. Carpenter Chair Professor of Religion, Psychology, and Culture and Womanist Thought at Vanderbilt University, "a research professor's vocation is nurtured by paying attention to where one experiences passion and a deep sense of belonging." This involves tasks such as "conducted literature reviews including: relevant government policy, policy evaluations, economic impact analyses, and scientific journal articles," and "synthesized and characterized colloidal room-temperature ferromagnetic cofe2o4 nanoparticles." Additionally, research professors are often involved in teaching subjects related to their field of study, such as "teach the scientific research methods laboratory" and "lectured undergraduate and graduate courses within the fields of exercise science and/or nutrition both presence and on-line."

Here are examples of responsibilities from real research professor resumes:

- Research lead to important biomarkers for stages of microglial activation.

- Manage social media publications to spread awareness and notifications on Facebook.

- Publish reports and papers, submit program applications to NIH, DTRA and DARPA.

- Focuse on the chemical synthesis of sulfate dendrimer molecules for heparin-like coagulant activity.

- Produce accurate results in Stata using appropriate statistical tests and regression models for given dataset.

- Conduct statistical analyses and writing programs in SAS and STATA for sophisticate multivariate linear or non-linear regression.

- Guide the technical implementation of an automate analysis system (electrophoresis station), with the enhancement of its operational efficiency.

- Work on recommendations to adapt Ukrainian tax system to EU standards in the field of direct taxation.

- Perform forensic analysis of chemical contaminants in fish tissues using multivariate statistical methods and GIS to discern primary regional contaminant sources.

Research professor skills and personality traits

We calculated that 16 % of Research Professors are proficient in Research Projects , Public Health , and Data Collection . They’re also known for soft skills such as Observation skills , Communication skills , and Interpersonal skills .

We break down the percentage of Research Professors that have these skills listed on their resume here:

Managed 6 simultaneous research projects ranging from education interventions to charity giving.

Performed research to ascertain a needs assessment for developing public health curriculum.

Involved in data collection and analysis with the mentor.

Nominated as the best Instructor within the Mathematics Department.

Machine learning and time series research High performance scientific computing in R, Python, SQL, and Matlab.

Teach the Scientific Research Methods Laboratory.

Most research professors use their skills in "research projects," "public health," and "data collection" to do their jobs. You can find more detail on essential research professor responsibilities here:

Observation skills. To carry out their duties, the most important skill for a research professor to have is observation skills. Their role and responsibilities require that "medical scientists conduct experiments that require monitoring samples and other health-related data." Research professors often use observation skills in their day-to-day job, as shown by this real resume: "manipulated primary economic data from survey translated/coded the primary data from observation by using stata, ms access and excel. "

Communication skills. Another soft skill that's essential for fulfilling research professor duties is communication skills. The role rewards competence in this skill because "medical scientists must be able to explain their research in nontechnical ways." According to a research professor resume, here's how research professors can utilize communication skills in their job responsibilities: "coordinated with post-doctoral network of media and communication researchers on methodological and theoretical developments derived from research. "

Most common research professor skills

The three companies that hire the most research professors are:

- UT Health San Antonio 2 research professors jobs

- University of Virginia 2 research professors jobs

- PSEA 2 research professors jobs

Choose from 10+ customizable research professor resume templates

Compare different research professors

Research professor vs. scientist.

A scientist is responsible for researching and analyzing the nature and complexities of the physical world to identify discoveries that would improve people's lives and ignite scientific knowledge for society. Scientists' duties differ in their different areas of expertise, but all of them must have a broad comprehension of scientific disciplines and methods to support their experiments and investigations. They collect the sample for their research, record findings, create research proposals, and release publications. A scientist must know how to utilize laboratory equipment to support the study and drive results efficiently and accurately.

There are some key differences in the responsibilities of each position. For example, research professor responsibilities require skills like "public health," "mathematics," "python," and "scholarship." Meanwhile a typical scientist has skills in areas such as "chemistry," "patients," "cell culture," and "java." This difference in skills reveals the differences in what each career does.

Research professor vs. Associate scientist

An Associate Scientist assists in various experiments and research, working under the direction of a lead scientist. Their specialties may include biological life sciences, geo-science, atmospheric physics, and computing.

In addition to the difference in salary, there are some other key differences worth noting. For example, research professor responsibilities are more likely to require skills like "research projects," "public health," "mathematics," and "python." Meanwhile, an associate scientist has duties that require skills in areas such as "chemistry," "patients," "cell culture," and "gmp." These differences highlight just how different the day-to-day in each role looks.

Research professor vs. Fellow

A fellow's responsibility will depend on the organization or industry where one belongs. However, most of the time, a fellow's duty will revolve around conducting research and analysis, presiding discussions and attending dialogues, handle lectures while complying with the guidelines or tasks set by supervisors, and assist in various projects and activities. Furthermore, a fellow must adhere to the institution or organization's policies and regulations at all times, meet all the requirements and outputs involved, and coordinate with every person in the workforce.

The required skills of the two careers differ considerably. For example, research professors are more likely to have skills like "scholarship," "research methods," "conduct research," and "organic chemistry." But a fellow is more likely to have skills like "patients," "professional development," "veterans," and "math."

Research professor vs. Senior scientist

A senior scientist is usually in charge of overseeing experiments and evaluating junior scientists' performance, especially in laboratory settings. Moreover, it is also their responsibility to assess every progress report to ensure it's accuracy and validity. As a senior scientist in the field, it is essential to lead and encourage fellow scientists in their joint pursuit for scientific innovations, all while adhering to the laboratory's standards and policies.

Types of research professor

Adjunct professor, research fellow.

Updated June 25, 2024

Editorial Staff

The Zippia Research Team has spent countless hours reviewing resumes, job postings, and government data to determine what goes into getting a job in each phase of life. Professional writers and data scientists comprise the Zippia Research Team.

- Zippia Careers

- Life, Physical, and Social Science Industry

- Research Professor

- What Does A Research Professor Do

Browse life, physical, and social science jobs