Welcome to the United Nations

30 years on, South Africa still dismantling racism and apartheid’s legacy

Get monthly e-newsletter.

Rethabile Ratsomo said it’s the little things that remind her of her perceived “place” in South African society.

There are the verbal slights and side-eye in workspaces, where she’s been viewed as a B-BBEE hire (The Broad-Based Black Economic Empowerment programme in South African that seeks to advance and transform the participation of black people in the country’s economy) and therefore not capable of doing the work. There are the passive-aggressive comments from colleagues, constantly complimenting her on how well she speaks English. She has lived through the daily microaggressions that form part of her life.

“I am a born-free and despite being born after the advent of democracy in South Africa, my race continues to play a huge role in my being, as a South African,” Ratsomo said, 29, who currently works at the Anti-Racism Network and the Ahmed Kathrada Foundation. “Many people continue to normalise racial discrimination and perpetuate harmful behaviours. Racism remains rife.”

Thirty years since the end of Apartheid, South Africa still grapples with its legacy. Unequal access to education, unequal pay, segregated communities and massive economic disparities persists, much of it is reinforced by existing institutions and attitudes. How is it that racism and its accompanying discrimination continues to hold such sway in this, majority Black populated and Black governed nation?

Racism has deep roots in the economic, spatial and social fabric of this country. It reflects the legacy of oppression and subjugation from apartheid and colonialism. While progress has been made to eliminate the scourge of racism it requires everyone to do their part for it be eliminated, said Abigail Noko, Representative for UN Human Rights Regional Office of Southern Africa (OHCHR ROSA)

“Dismantling such entrenched racist and discriminatory systems requires commitment, leadership, dialogue and advocacy to put in place anti-racist policies that implement human rights norms and provide a framework to help address and rectify these injustices and promote equality,” she added.

Free your mind and the rest will follow

The project of dismantling racist systems in a place like South Africa, must go hand in hand with the process of decolonization – both at an institutional and an individual level, said Professor Tshepo Madlingozi, a Commissioner at the South African Human Rights Commission (SAHRC).

“History has shown that unless you have decolonized your mind, you are going to step into the shoes of the oppressor and oppress other people over and over again,” he said.

Madlingozi’s comments were part of a panel discussion on dismantling racist systems in South Africa, which took place during the Human Rights Festival in Johannesburg in March, which aligns with national Human Rights Day and the International Day for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination. The discussion, sponsored by OHCHR ROSA, had three panellists providing their answers to the overarching question, how can racism present in the “rainbow nation” be dismantled to bring about freedom, equality, and justice for all?

Samkelo Mkhomi, a social justice and equality activist in her 20s, agreed that an internal mindset change was needed, especially among young people. She said she noticed that many of her born-free peers, i.e., someone who was born after the advent of democracy in South Africa, harbour suspicious and distrustful attitudes toward other races. She mentioned a friend who has a distrust of all white people. When Mkhomi asked why, he told her “because of what they did in the past.” She called this deliberate lack of understanding among her peers as hereditary and a big stumbling block in moving forward.

“We have set perceptions and stereotypes that we've inherited from family, from social experiences, experiences that are not our own,” Mkhomi said. “And we've used that as a blueprint to view other people. Once you can get rid of that as young people, I feel like we can start moving on and dismantling racism.”

Madlingozi suggested one way to do this could be to not only focus on individual racist incidences, but also to bring more awareness, and push for policies in institutions that deconstruct current ways of working.

“What matters is, have we dismantled the institutions, the cultures that perpetuate racism,” he said. “Because unless you do that, you’ll have Black people, you will have a Black government that will continue to perpetuate racism because that is the nature of institutionalised racism. So yes, let’s focus on individual human rights. Let’s focus on social justice, but where it matters the most is structural institutionalized oppression.”

Casting a long shadow

The scars of Apartheid run deep, leaving a legacy of segregation, discrimination and inequality. This is evidenced by the stark economic disparities in the country. A 2022 World Bank report on inequality in southern Africa gave South Africa the unfortunate distinction of being the most unequal country in the world.

The report stated that 80 percent of the country’s wealth was in the hands of 10 percent of the population. And it is the Black population who factor the most into the poorest category. The report places the blame for the income disparities directly on race.

“The legacy of colonialism and Apartheid rooted in racial and spatial segregation continues to reinforce inequality,” the report states.

The spatial divide mirrors the economic one.

The evil genius of Apartheid was the segregation project, as it allowed the Government to not only separate people based on arbitrary categorisations, but through this create material differences between the communities to reinforce the idea of actual racial differences, said Tessa Dooms. These racial classifications also encouraged the idea that the different groups needed to compete for basic human rights, dignity and economic opportunities, she added.

“The Apartheid government didn’t just give people categories, they gave real live material meaning to those categories,” said Dooms, Director of Programmes for Rivonia Circle during the panel discussion. “As long as those categories mean something in the world, we still have work to do, to undo Apartheid, to undo colonialism, to decolonize.”

To do this, Dooms recommended practical vision as to what a decolonized South Africa would look like, being very specific about the results wanted. She also called on the privileged groups to do the heavy lifting of helping to create more equality. Until those with privileges work to broaden access to them, the cycle will continue, Dooms added.

“We cannot leave creating a more just world to the people who are most affected by injustice,” she said. “It’s not fair, it’s not right and it won’t work.”

Taking concrete action

Globally, South Africa’s post-Apartheid long walk to freedom has garnered an international reputation as a leader in global efforts to combat racism. In 2001, South Africa hosted the World Conference Against Racism, Racial Discrimination, Xenophobia and Related Intolerance (WCAR), which resulted in the Durban Declaration and Programme of Action (DDPA). The DDPA is a roadmap, providing concrete measures for States to combat racism, discrimination and xenophobia and related intolerance.

One of the big recommendations was to have each country create its own National Action Plan (NAP). The plan is a means through which governments locally codify their commitment to taking action, with concrete steps on how they will combat racism. South Africa launched its plan in 2019, with OHCHR ROSA providing technical assistance. This assistance took many forms including participation in the consultations that led up to the final NAP and helping to set up support structures for its implementation, and support for research and other work to help develop systems for data collection on issues related to the NAP.

“Human rights play crucial role in dismantling racism by providing a framework for addressing and rectifying historical injustices, promoting equality, and ensuring that all individuals are treated fairly and with dignity,” Noko said

Various other sectors have pioneered innovative approaches to chip away at Apartheid’s remnants. Corporate and governmental diversity programmes, such as B-BBEE, and the Employment Equity Amendment Bill of 2020, aim to promote diversity and equity in the workplace.

Ratsomo of the Ahmed Kathrada Foundation said these and other efforts to address the underlying issue of what to do about that still exists in the country are key to taking it down. Everyone must learn, speak up, and act on racism, racial discrimination and related intolerances, she said.

“The beginning point to tackle and dismantle systemic racism is to understand that being anti-racist does not only mean being against racism,” she said. “It also means being active and speaking out against racism whenever you see it happen. The more we understand racism, the easier it becomes to identify when it happens, which allows us to speak out and act against it when we see it happening.”

Also in this issue

Guiding the Future: UN launches new panel on critical energy transition minerals

We must do more to prevent genocide

Football saved me from genocide; now I promote peace with it

Transforming Artisanal Mining Can Be Beneficial for People and the Planet

Kwibuka30: Learning from the past, safeguarding the future against genocide

Many African nations are making progress in the rule of law

Streamlining Egypt’s food value chain through technology

Lessons post the 1994 genocide against the Tutsi in Rwanda: we must speak out against discrimination and prejudice

We shouldn’t have to beg or negotiate for women rights

Creating credible carbon market in Africa

REMEMBER.UNITE.RENEW.

Reforming global financial structures: Paving the way for financing for sustainable development in Africa

Breaking gender barriers through education

Claver Irakoze: Bridging Generations Through the Memory of the 1994 Genocide against the Tutsi in Rwanda

Accelerating Africa’s Journey Towards a Prosperous Future

Sudan: Horrific violations and abuses as fighting spreads - report

More from africa renewal.

Hate is taught: it can be fought

Two years after the killing of George Floyd, urgency to end racial inequalities and discrimination beckons

Homophobia: The Violence of Intolerance

30 years on, South Africa still dismantling racism and apartheid’s legacy

How is it that racism and its accompanying discrimination continues to hold such sway in this, majority Black populated and Black governed nation?

Rethabile Ratsomo said it’s the little things that remind her of her perceived “place” in South African society.

There are the verbal slights and side-eye in workspaces, where she’s been viewed as a B-BBEE hire (The Broad-Based Black Economic Empowerment programme in South African that seeks to advance and transform the participation of black people in the country’s economy) and therefore not capable of doing the work. There are the passive-aggressive comments from colleagues, constantly complimenting her on how well she speaks English. She has lived through the daily microaggressions that form part of her life.

“I am a born-free and despite being born after the advent of democracy in South Africa, my race continues to play a huge role in my being, as a South African,” Ratsomo said, 29, who currently works at the Anti-Racism Network and the Ahmed Kathrada Foundation. “Many people continue to normalise racial discrimination and perpetuate harmful behaviours. Racism remains rife.”

Thirty years since the end of Apartheid, South Africa still grapples with its legacy. Unequal access to education, segregated communities and massive economic disparities persists, much of it is reinforced by existing institutions and attitudes. How is it that racism and its accompanying discrimination continues to hold such sway in this, majority Black populated and Black governed nation?

Racism has deep roots in the economic, spatial and social fabric of this country. It reflects the legacy of oppression and subjugation from apartheid and colonialism. While progress has been made to eliminate the scourge of racism it requires everyone to do their part for it be eliminated, said Abigail Noko, Representative for UN Human Rights Regional Office of Southern Africa (OHCHR ROSA)

“Dismantling such entrenched racist and discriminatory systems requires commitment, leadership, dialogue and advocacy to put in place anti-racist policies that implement human rights norms and provide a framework to help address and rectify these injustices and promote equality,” she added.

Free your mind and the rest will follow

The project of dismantling racist systems in a place like South Africa, must go hand in hand with the process of decolonization – both at an institutional and an individual level, said Professor Tshepo Madlingozi, a Commissioner at the South African Human Rights Commission (SAHRC).

“History has shown that unless you have decolonized your mind, you are going to step into the shoes of the oppressor and oppress other people over and over again,” he said.

Madlingozi’s comments were part of a panel discussion on dismantling racist systems in South Africa, which took place during the Human Rights Festival in Johannesburg in March, which aligns with national Human Rights Day and the International Day for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination. The discussion, sponsored by OHCHR ROSA, had three panelists providing their answers to the overarching question, how can racism present in the “rainbow nation” be dismantled to bring about freedom, equality, and justice for all?

Samkelo Mkhomi, a social justice and equality activist in her 20s, agreed that an internal mindset change was needed, especially among young people. She said she noticed that many of her born-free peers, i.e., someone who was born after the advent of democracy in South Africa, harbour suspicious and distrustful attitudes toward other races. She mentioned a friend who has a distrust of all white people. When Mkhomi asked why, he told her “because of what they did in the past.” She called this deliberate lack of understanding among her peers as hereditary and a big stumbling block in moving forward.

“We have set perceptions and stereotypes that we've inherited from family, from social experiences, experiences that are not our own,” Mkhomi said. “And we've used that as a blueprint to view other people. Once you can get rid of that as young people, I feel like we can start moving on and dismantling racism.”

Madlingozi suggested one way to do this could be to not only focus on individual racist incidences, but also to bring more awareness, and push for policies in institutions that deconstruct current ways of working.

“What matters is, have we dismantled the institutions, the cultures that perpetuate racism,” he said. “Because unless you do that, you’ll have Black people, you will have a Black government that will continue to perpetuate racism because that is the nature of institutionalised racism. So yes, let’s focus on individual human rights. Let’s focus on social justice, but where it matters the most is structural institutionalized oppression.”

Casting a long shadow

The scars of Apartheid run deep, leaving a legacy of segregation, discrimination and inequality. This is evidenced by the stark economic disparities in the country. A 2022 World Bank report on inequality in southern Africa gave South Africa the unfortunate distinction of being the most unequal country in the world.

The report stated that 80 percent of the country’s wealth was in the hands of 10 percent of the population. And it is the Black population who factor the most into the poorest category. The report places the blame for the income disparities directly on race.

“The legacy of colonialism and Apartheid rooted in racial and spatial segregation continues to reinforce inequality,” the report states.

The spatial divide mirrors the economic one.

The evil genius of Apartheid was the segregation project, as it allowed the Government to not only separate people based on arbitrary categorizations, but through this create material differences between the communities to reinforce the idea of actual racial differences, said Tessa Dooms. These racial classifications also encouraged the idea that the different groups needed to compete for basic human rights, dignity and economic opportunities, she added.

“The Apartheid government didn’t just give people categories, they gave real live material meaning to those categories,” said Dooms, Director of Programmes for Rivonia Circle during the panel discussion. “As long as those categories mean something in the world, we still have work to do, to undo Apartheid, to undo colonialism, to decolonize.”

To do this, Dooms recommended practical vision as to what a decolonized South Africa would look like, being very specific about the results wanted. She also called on the privileged groups to do the heavy lifting of helping to create more equality. Until those with privileges work to broaden access to them, the cycle will continue, Dooms added.

“We cannot leave creating a more just world to the people who are most affected by injustice,” she said. “It’s not fair, it’s not right and it won’t work.”

Taking concrete action

Globally, South Africa’s post-Apartheid long walk to freedom has garnered an international reputation as a leader in global efforts to combat racism. In 2001, South Africa hosted the World Conference Against Racism, Racial Discrimination, Xenophobia and Related Intolerance (WCAR), which resulted in the Durban Declaration and Programme of Action (DDPA). The DDPA is a roadmap, providing concrete measures for States to combat racism, discrimination and xenophobia and related intolerance.

One of the big recommendations was to have each country create its own National Action Plan (NAP). The plan is a means through which governments locally codify their commitment to taking action, with concrete steps on how they will combat racism. South Africa launched its plan in 2019, with OHCHR ROSA providing technical assistance. This assistance took many forms including participation in the consultations that led up to the final NAP and helping to set up support structures for its implementation, and support for research and other work to help develop systems for data collection on issues related to the NAP.

“Human rights play crucial role in dismantling racism by providing a framework for addressing and rectifying historical injustices, promoting equality, and ensuring that all individuals are treated fairly and with dignity,” Noko said

Various other sectors have pioneered innovative approaches to chip away at Apartheid’s remnants. Corporate and governmental diversity programmes, such as B-BBEE, and the Employment Equity Amendment Bill of 2020, aim to promote diversity and equity in the workplace.

Ratsomo of the Ahmed Kathrada Foundation said these and other efforts to address the underlying issue of what to do about that still exists in the country are key to taking it down. Everyone must learn, speak up, and act on racism, racial discrimination and related intolerances, she said.

“The beginning point to tackle and dismantle systemic racism is to understand that being anti-racist does not only mean being against racism,” she said. “It also means being active and speaking out against racism whenever you see it happen. The more we understand racism, the easier it becomes to identify when it happens, which allows us to speak out and act against it when we see it happening.”

UN entities involved in this initiative

Goals we are supporting through this initiative.

- Games & Quizzes

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction & Top Questions

Apartheid legislation

- Opposition to apartheid

- The end of legislated apartheid

What is apartheid?

When did apartheid start, how did apartheid end, what is the apartheid era in south african history.

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- Khan Academy - Apartheid

- Academia - A Social History of the University Presses in Apartheid South Africa

- Gresham College - The Gospel of Apartheid

- Stanford University - The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute - Apartheid

- South African History Online - Apartheid and Reactions to It

- BlackPast - Apartheid

- Al Jazeera - South Africa: 30 years after apartheid, what has changed?

- GlobalSecurity.org - South Africa - Apartheid

- The Library of Economics and Liberty - Apartheid

- apartheid - Children's Encyclopedia (Ages 8-11)

- apartheid - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

- Table Of Contents

Apartheid ( Afrikaans : “apartness”) is the name of the policy that governed relations between the white minority and the nonwhite majority of South Africa during the 20th century. Although racial segregation had long been in practice there, the apartheid name was first used about 1948 to describe the racial segregation policies embraced by the white minority government. Apartheid dictated where South Africans, on the basis of their race, could live and work, the type of education they could receive, and whether they could vote. Events in the early 1990s marked the end of legislated apartheid, but the social and economic effects remained deeply entrenched.

Racial segregation had long existed in white minority-governed South Africa , but the practice was extended under the government led by the National Party (1948–94), and the party named its racial segregation policies apartheid ( Afrikaans : “apartness”). The Population Registration Act of 1950 classified South Africans as Bantu (black Africans), Coloured (those of mixed race), or white; an Asian (Indian and Pakistani) category was later added. Other apartheid acts dictated where South Africans, on the basis of their racial classification, could live and work, the type of education they could receive, whether they could vote, who they could associate with, and which segregated public facilities they could use.

Under the administration of the South African president F.W. de Klerk , legislation supporting apartheid was repealed in the early 1990s, and a new constitution—one that enfranchised blacks and other racial groups—was adopted in 1993. All-race national elections held in 1994 resulted in a black majority government led by prominent anti-apartheid activist Nelson Mandela of the African National Congress party. Although these developments marked the end of legislated apartheid, the social and economic effects of apartheid remained deeply entrenched in South African society.

The apartheid era in South African history refers to the time that the National Party led the country’s white minority government, from 1948 to 1994. Apartheid ( Afrikaans : “apartness”) was the name that the party gave to its racial segregation policies, which built upon the country’s history of racial segregation between the ruling white minority and the nonwhite majority. During this time, apartheid policy determined where South Africans, on the basis of their race, could live and work, the type of education they could receive, whether they could vote, who they could associate with, and which segregated public facilities they could use.

Recent News

Trusted Britannica articles, summarized using artificial intelligence, to provide a quicker and simpler reading experience. This is a beta feature. Please verify important information in our full article.

This summary was created from our Britannica article using AI. Please verify important information in our full article.

apartheid , policy that governed relations between South Africa ’s white minority and nonwhite majority for much of the latter half of the 20th century, sanctioning racial segregation and political and economic discrimination against nonwhites. Although the legislation that formed the foundation of apartheid had been repealed by the early 1990s, the social and economic repercussions of the discriminatory policy persisted into the 21st century.

(Read Desmond Tutu’s Britannica entry on the apartheid commission.)

Racial segregation , sanctioned by law, was widely practiced in South Africa before 1948. But when the National Party , led by Daniel F. Malan , gained office that year, it extended the policy and gave it the name apartheid . The implementation of apartheid, often called “separate development” since the 1960s, was made possible through the Population Registration Act of 1950, which classified all South Africans as either Bantu (all Black Africans), Coloured (those of mixed race), or white. A fourth category—Asian (Indian and Pakistani)—was later added. One of the other most significant acts in terms of forming the basis of the apartheid system was the Group Areas Act of 1950. It established residential and business sections in urban areas for each race, and members of other races were barred from living, operating businesses, or owning land in them—which led to thousands of Coloureds, Blacks, and Indians being removed from areas classified for white occupation. In practice, this act and two others in 1954 and 1955, which became known collectively as the Land Acts , completed a process that had begun with similar Land Acts adopted in 1913 and 1936: the end result was to set aside more than 80 percent of South Africa’s land for the white minority. To help enforce the segregation of the races and prevent Blacks from encroaching on white areas, the government strengthened the existing “pass” laws , which required nonwhites to carry documents authorizing their presence in restricted areas.

Other acts also led to physical separation of the races. Under the Bantu Authorities Act of 1951, the government reestablished tribal organizations for Black Africans, and the Promotion of Bantu Self-Government Act of 1959 created 8 (later expanded to 10 )African homelands, or Bantustans . The Bantu Homelands Citizenship Act of 1970 made every Black South African, irrespective of actual residence, a citizen of one of the Bantustans, which were organized on the basis of ethnic and linguistic groupings defined by white ethnographers. Blacks were stripped of their South African citizenship and thereby excluded from the South African body politic . The South African government manipulated homeland politics so that compliant chiefs controlled the administrations of most of those territories. Four of the Bantustans— Transkei , Bophuthatswana , Venda , and Ciskei —were later granted independence as republics, though none was ever recognized by a foreign government, and the remaining Bantustans had varying degrees of self-government. Regardless of their independence or self-governing status, all the Bantustans remained dependent, both politically and economically, on South Africa. The dependence of the South African economy on nonwhite labour, though, made it difficult for the government to carry out this policy of separate development.

Separate educational standards were established for nonwhites. The Bantu Education Act (1953) provided for the creation of state-run schools, which Black children were required to attend, with the goal of training the children for the manual labour and menial jobs that the government deemed suitable for those of their race. The Extension of University Education Act (1959) largely prohibited established universities from accepting nonwhite students. The government created new ethnic university colleges—one each for Coloureds, Indians, and Zulus and one for Sotho , Tswana , and Venda students as well as a medical school for Blacks.

Other laws were also passed to legalize and institutionalize the apartheid system. The Prohibition of Mixed Marriages Act (1949) and the Immorality Amendment Act (1950) prohibited interracial marriage or sex. The Suppression of Communism Act (1950) defined communism and its aims broadly to include any opposition to the government and empowered the government to detain anyone it thought might further “communist” aims. The Indemnity Act (1961) made it legal for police officers to commit acts of violence, to torture , or to kill in the pursuit of official duties.

The policies dictating the physical and political separation of racial groups were referred to as “grand apartheid,” while the laws and regulations that segregated South Africans in daily activities were known as “petty apartheid”—for example, those that dictated which transportation, recreation, or dining options one could utilize based on race.

South Africa: 30 Years On, South Africa Still Dismantling Racism and Apartheid's Legacy

Rethabile Ratsomo said it's the little things that remind her of her perceived "place" in South African society.

There are the verbal slights and side-eye in workspaces, where she's been viewed as a B-BBEE hire (The Broad-Based Black Economic Empowerment programme in South African that seeks to advance and transform the participation of black people in the country's economy) and therefore not capable of doing the work. There are the passive-aggressive comments from colleagues, constantly complimenting her on how well she speaks English. She has lived through the daily microaggressions that form part of her life.

"I am a born-free and despite being born after the advent of democracy in South Africa, my race continues to play a huge role in my being, as a South African," Ratsomo said, 29, who currently works at the Anti-Racism Network and the Ahmed Kathrada Foundation. "Many people continue to normalise racial discrimination and perpetuate harmful behaviours. Racism remains rife."

Thirty years since the end of Apartheid, South Africa still grapples with its legacy. Unequal access to education, unequal pay, segregated communities and massive economic disparities persists, much of it is reinforced by existing institutions and attitudes. How is it that racism and its accompanying discrimination continues to hold such sway in this, majority Black populated and Black governed nation?

Racism has deep roots in the economic, spatial and social fabric of this country. It reflects the legacy of oppression and subjugation from apartheid and colonialism. While progress has been made to eliminate the scourge of racism it requires everyone to do their part for it be eliminated, said Abigail Noko, Representative for UN Human Rights Regional Office of Southern Africa (OHCHR ROSA)

"Dismantling such entrenched racist and discriminatory systems requires commitment, leadership, dialogue and advocacy to put in place anti-racist policies that implement human rights norms and provide a framework to help address and rectify these injustices and promote equality," she added.

Free your mind and the rest will follow

The project of dismantling racist systems in a place like South Africa, must go hand in hand with the process of decolonization - both at an institutional and an individual level, said Professor Tshepo Madlingozi, a Commissioner at the South African Human Rights Commission (SAHRC).

"History has shown that unless you have decolonized your mind, you are going to step into the shoes of the oppressor and oppress other people over and over again," he said.

Madlingozi's comments were part of a panel discussion on dismantling racist systems in South Africa, which took place during the Human Rights Festival in Johannesburg in March, which aligns with national Human Rights Day and the International Day for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination. The discussion, sponsored by OHCHR ROSA, had three panellists providing their answers to the overarching question, how can racism present in the "rainbow nation" be dismantled to bring about freedom, equality, and justice for all?

Samkelo Mkhomi, a social justice and equality activist in her 20s, agreed that an internal mindset change was needed, especially among young people. She said she noticed that many of her born-free peers, i.e., someone who was born after the advent of democracy in South Africa, harbour suspicious and distrustful attitudes toward other races. She mentioned a friend who has a distrust of all white people. When Mkhomi asked why, he told her "because of what they did in the past." She called this deliberate lack of understanding among her peers as hereditary and a big stumbling block in moving forward.

"We have set perceptions and stereotypes that we've inherited from family, from social experiences, experiences that are not our own," Mkhomi said. "And we've used that as a blueprint to view other people. Once you can get rid of that as young people, I feel like we can start moving on and dismantling racism."

Madlingozi suggested one way to do this could be to not only focus on individual racist incidences, but also to bring more awareness, and push for policies in institutions that deconstruct current ways of working.

"What matters is, have we dismantled the institutions, the cultures that perpetuate racism," he said. "Because unless you do that, you'll have Black people, you will have a Black government that will continue to perpetuate racism because that is the nature of institutionalised racism. So yes, let's focus on individual human rights. Let's focus on social justice, but where it matters the most is structural institutionalized oppression."

Casting a long shadow

The scars of Apartheid run deep, leaving a legacy of segregation, discrimination and inequality. This is evidenced by the stark economic disparities in the country. A 2022 World Bank report on inequality in southern Africa gave South Africa the unfortunate distinction of being the most unequal country in the world.

The report stated that 80 percent of the country's wealth was in the hands of 10 percent of the population. And it is the Black population who factor the most into the poorest category. The report places the blame for the income disparities directly on race.

"The legacy of colonialism and Apartheid rooted in racial and spatial segregation continues to reinforce inequality," the report states.

The spatial divide mirrors the economic one.

The evil genius of Apartheid was the segregation project, as it allowed the Government to not only separate people based on arbitrary categorisations, but through this create material differences between the communities to reinforce the idea of actual racial differences, said Tessa Dooms. These racial classifications also encouraged the idea that the different groups needed to compete for basic human rights, dignity and economic opportunities, she added.

"The Apartheid government didn't just give people categories, they gave real live material meaning to those categories," said Dooms, Director of Programmes for Rivonia Circle during the panel discussion. "As long as those categories mean something in the world, we still have work to do, to undo Apartheid, to undo colonialism, to decolonize."

To do this, Dooms recommended practical vision as to what a decolonized South Africa would look like, being very specific about the results wanted. She also called on the privileged groups to do the heavy lifting of helping to create more equality. Until those with privileges work to broaden access to them, the cycle will continue, Dooms added.

"We cannot leave creating a more just world to the people who are most affected by injustice," she said. "It's not fair, it's not right and it won't work."

Taking concrete action

Globally, South Africa's post-Apartheid long walk to freedom has garnered an international reputation as a leader in global efforts to combat racism. In 2001, South Africa hosted the World Conference Against Racism, Racial Discrimination, Xenophobia and Related Intolerance (WCAR), which resulted in the Durban Declaration and Programme of Action (DDPA). The DDPA is a roadmap, providing concrete measures for States to combat racism, discrimination and xenophobia and related intolerance.

Sign up for free AllAfrica Newsletters

Get the latest in African news delivered straight to your inbox

By submitting above, you agree to our privacy policy .

Almost finished...

We need to confirm your email address.

To complete the process, please follow the instructions in the email we just sent you.

There was a problem processing your submission. Please try again later.

One of the big recommendations was to have each country create its own National Action Plan (NAP). The plan is a means through which governments locally codify their commitment to taking action, with concrete steps on how they will combat racism. South Africa launched its plan in 2019, with OHCHR ROSA providing technical assistance. This assistance took many forms including participation in the consultations that led up to the final NAP and helping to set up support structures for its implementation, and support for research and other work to help develop systems for data collection on issues related to the NAP.

"Human rights play crucial role in dismantling racism by providing a framework for addressing and rectifying historical injustices, promoting equality, and ensuring that all individuals are treated fairly and with dignity," Noko said

Various other sectors have pioneered innovative approaches to chip away at Apartheid's remnants. Corporate and governmental diversity programmes, such as B-BBEE, and the Employment Equity Amendment Bill of 2020, aim to promote diversity and equity in the workplace.

Ratsomo of the Ahmed Kathrada Foundation said these and other efforts to address the underlying issue of what to do about that still exists in the country are key to taking it down. Everyone must learn, speak up, and act on racism, racial discrimination and related intolerances, she said.

"The beginning point to tackle and dismantle systemic racism is to understand that being anti-racist does not only mean being against racism," she said. "It also means being active and speaking out against racism whenever you see it happen. The more we understand racism, the easier it becomes to identify when it happens, which allows us to speak out and act against it when we see it happening."

Read the original article on Africa Renewal .

- South Africa

- Southern Africa

AllAfrica publishes around 500 reports a day from more than 100 news organizations and over 500 other institutions and individuals , representing a diversity of positions on every topic. We publish news and views ranging from vigorous opponents of governments to government publications and spokespersons. Publishers named above each report are responsible for their own content, which AllAfrica does not have the legal right to edit or correct.

Articles and commentaries that identify allAfrica.com as the publisher are produced or commissioned by AllAfrica . To address comments or complaints, please Contact us .

AllAfrica is a voice of, by and about Africa - aggregating, producing and distributing 500 news and information items daily from over 100 African news organizations and our own reporters to an African and global public. We operate from Cape Town, Dakar, Abuja, Johannesburg, Nairobi and Washington DC.

- Support our work

- Sign up for our newsletter

- For Advertisers

- © 2024 AllAfrica

- Privacy Policy

- About SAFLII

- Terms of Use

Potchefstroom Electronic Law Journal // Potchefstroomse Elektroniese Regsblad

Hate speech and racist slurs in the south african context: where to start (vol 23) [2020] per 12.

|

- Society and Politics

- Art and Culture

- Biographies

- Publications

A history of Apartheid in South Africa

Background and policy of apartheid

Before we can look at the history of the apartheid period it is necessary to understand what apartheid was and how it affected people.

What was apartheid?

Translated from the Afrikaans meaning 'apartness', apartheid was the ideology supported by the National Party (NP) government and was introduced in South Africa in 1948. Apartheid called for the separate development of the different racial groups in South Africa. On paper it appeared to call for equal development and freedom of cultural expression, but the way it was implemented made this impossible. Apartheid made laws forced the different racial groups to live separately and develop separately, and grossly unequally too. It tried to stop all inter-marriage and social integration between racial groups. During apartheid, to have a friendship with someone of a different race generally brought suspicion upon you, or worse. More than this, apartheid was a social system which severely disadvantaged the majority of the population, simply because they did not share the skin colour of the rulers. Many were kept just above destitution because they were 'non-white'.

In basic principles, apartheid did not differ that much from the policy of segregation of the South African governments existing before the Afrikaner Nationalist Party came to power in 1948. The main difference is that apartheid made segregation part of the law. Apartheid cruelly and forcibly separated people, and had a fearsome state apparatus to punish those who disagreed. Another reason why apartheid was seen as much worse than segregation, was that apartheid was introduced in a period when other countries were moving away from racist policies. Before World War Two the Western world was not as critical of racial discrimination, and Africa was colonized in this period. The Second World War highlighted the problems of racism, making the world turn away from such policies and encouraging demands for decolonization. It was during this period that South Africa introduced the more rigid racial policy of apartheid.

People often wonder why such a policy was introduced and why it had so much support. Various reasons can be given for apartheid, although they are all closely linked. The main reasons lie in ideas of racial superiority and fear. Across the world, racism is influenced by the idea that one race must be superior to another. Such ideas are found in all population groups. The other main reason for apartheid was fear, as in South Africa the white people are in the minority, and many were worried they would lose their jobs, culture and language. This is obviously not a justification for apartheid, but explains how people were thinking.

Apartheid Laws

Numerous laws were passed in the creation of the apartheid state. Here are a few of the pillars on which it rested:

Population Registration Act, 1950 This Act demanded that people be registered according to their racial group. This meant that the Department of Home affairs would have a record of people according to whether they were white, coloured, black, Indian or Asian. People would then be treated differently according to their population group, and so this law formed the basis of apartheid. It was however not always that easy to decide what racial group a person was part of, and this caused some problems.

Group Areas Act, 1950 This was the act that started physical separation between races, especially in urban areas. The act also called for the removal of some groups of people into areas set aside for their racial group.

Promotion of Bantu Self-Government Act, 1959 This Act said that different racial groups had to live in different areas. Only a small percentage of South Africa was left for black people (who comprised the vast majority) to form their 'homelands'. This Act also got rid of 'black spots' inside white areas, by moving all black people out of the city. Well known removals were those in District 6, Sophiatown and Lady Selborne. These black people were then placed in townships outside of the town. They could not own property here, only rent it, as the land could only be white owned. This Act caused much hardship and resentment. People lost their homes, were moved off land they had owned for many years and were moved to undeveloped areas far away from their place of work.

Some other important laws were the:

Prohibition of Mixed Marriages Act, 1949 Immorality Amendment Act, 1950 Separate Representation of Voters Act, 1951

Resistance before 1960

Resistance to apartheid came from all circles, and not only, as is often presumed, from those who suffered the negative effects of discrimination. Criticism also came from other countries, and some of these gave support to the South African freedom movements.

Some of the most important organizations involved in the struggle for liberation were the African National Congress (ANC), the Pan-Africanist Congress (PAC), the Inkatha Freedom Party ( IFP), the Black Consciousness Movement (BCM) and the United Democratic Front (UDF). There were also Indian and Coloured organized resistance movements (e.g. the Natal Indian Congress (NIC), the Coloured People's Organisation), white organized groups (e.g. the radical Armed Resistance Movement (ARM), and Black Sash) and church based groups (the Christian Institute). We shall consider the ANC.

The ANC was formed in Bloemfontein in 1912, soon after the Union of South Africa. Originally it was called the South African Native National Congress (SANNC). It was started as a movement for the Black elite, that is those Blacks who were educated. In 1919, the ANC sent a deputation to London to plead for a new deal for South African blacks, but there was no change to their position.

The history of resistance by the ANC goes through three phases. The first was dialogue and petition; the second direct opposition and the last the period of exiled armed struggle. In 1949, just after apartheid was introduced, the ANC started on a more militant path, with the Youth League playing a more important role. The ANC introduced their Programme of Action in 1949, supporting strike action, protests and other forms of non-violent resistance. Nelson Mandela, Oliver Tambo and Walter Sisulu started to play an important role in the ANC in this period. In 1952 the ANC started the Defiance Campaign. This campaign called on people to purposefully break apartheid laws and offer themselves for arrest. It was hoped that the increase in prisoners would cause the system to collapse and get international support for the ANC. Black people got onto 'white buses', used 'white toilets', entered into 'white areas' and refused to use passes. Despite 8 000 people ending up in jail, the ANC caused no threat to the apartheid regime.

The ANC continued along the same path during the rest of the 1950s, until in 1959 some members broke away and formed the PAC. These members wanted to follow a more violent and militant route, and felt that success could not be reached through the ANC's method.

Apartheid South Africa In the 1960s – Photos Of The Black And White Years

Collections in the Archives

Know something about this topic.

Towards a people's history

Students on the frontline: South Africa and the US share a history of protest against white supremacy

Professor of History, Jackson State University

Disclosure statement

Rico Devara Chapman receives funding from the Fulbright U.S. Scholars Program.

View all partners

Every year on 16 June, South Africa commemorates the revolt of black school children against the inferior “ bantu education ” system on that day in 1976. The horror of police shooting and killing unarmed children caused a global uproar. Historian Rico Devara Chapman’s research interests include a focus on the African diaspora’s historical and contemporary struggles for justice, particularly student activism in the United States and South Africa . We asked him about similarities between student revolts under the systems of apartheid in South Africa and Jim Crow in the United States.

You draw parallels between Jim Crow and apartheid. Please explain.

Apartheid was officially made policy in 1948 in South Africa, designating Africans to “ bantustans ”. These were the 10 undeveloped areas African people were deemed to belong in, where they could exercise nominal self-rule, separate from the minority white population.

It became mandatory for Africans to carry passbooks – identity books that controlled their movements. Apartheid also institutionalised segregation in all public places, including schools and institutions of higher learning. Though some of these measures were in place before 1948, they were extended under apartheid.

Jim Crow laws in America began as early as 1865, similarly confining African Americans to designated neighbourhoods, hospitals and schools. The name “Jim Crow” originated in the early 19th century from minstrel shows that depicted Black people as unintelligent.

Both systems were set up to keep and advance white supremacy. They are the context for Black youth resistance in both countries.

Read more: How the Jim Crow internet is pushing back against Black Lives Matter

The African youth movements in South Africa and the American South had long histories with high points and low points of participation. Both movements used tactics of non-violent direct action , non-violent direct action , civil disobedience and armed resistance .

There has been a long history of resistance to white hegemony in both countries, going beyond the liberation struggle in South Africa and the civil rights movement in America.

African youth resistance to white oppression throughout Africa had similar tactics and strategies.

How did student resistance in South Africa and the US manifest?

During the 1960s age of Jim Crow America, students from historically Black colleges and universities would conduct sit-in protests at segregated lunch counters and segregated libraries , and wade in at segregated beaches, challenging the retrogressive way of life in the American South.

They were fed up with second-class citizenship and went to jail by the hundreds to ultimately defeat the segregationists’ forces . Though challenges continued, Jim Crow segregation was legally abolished in 1964 with the enactment of the Civil Rights Act in 1964, followed by the Voting Rights Act in 1965.

In South Africa during the 1970s, students used similar tactics to break the back of apartheid. Students from high school up through tertiary education would be on the front lines fighting apartheid. The policy also designated them as second-class citizens and forced them to attend separate educational institutions .

Read more: South Africa's epochal 1976 uprisings shouldn't be reduced to a symbolic ritual

South African students would boycott, strike and physically fight the security forces in charge of maintaining the apartheid system. When liberation organisations such as the African National Congress and the Pan Africanist Congress of Azania were banned in 1960, and their leaders imprisoned or forced to leave the country forever , it was the youth who continued the resistance movement.

Students used the campus and took to the streets to fight for equal rights. These protests happened at different points in American and South African history yet were closely related in their core values.

Did the activists have any impact beyond student politics?

The Black Power movement in America would come to influence the Black Consciousness movement in South Africa. The South African liberation struggle shared some fundamental characteristics with the modern civil rights movement in the United States.

A number of leaders began their lifelong career as activists and movement organisers on college campuses where many of the initial struggles for social change took place. Kwame Ture (formerly Stokely Carmichael) was a lead organiser in the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee . He led the call for Black Power in the United States.

Read more: Why Biko's Black Consciousness philosophy resonates with youth today

Steve Biko , founding member of the South African Students Organisation , was a leader of the ideology of Black Consciousness in South Africa.

The two movements galvanised African people throughout the world. They had similar programmes and objectives, and faced related challenges in regard to white liberal involvement.

How has student activism changed in both countries?

When liberation struggle leader Nelson Mandela was released from prison and eventually elected president of South Africa in 1994, student movements had to adjust. They now had to engage an African government around various student concerns that were now non-racial. There were student protests post-1994 that addressed tuition fee increases.

As students in the US witnessed the election of the nation’s first Black president, Barack Obama , in 2008, jubilation filled the air. However, racism in the country intensified.

The continued harassment and killing of young Black men, such as Trayvon Martin and Mike Brown , sparked young people to once again take to the streets through the #BlackLivesMatter movement developed in 2013-2014 as a response.

Economic disparities and unaffordable tuition fees prompted several months of protests by South African students under the #FeesMustFall banner in 2015-2016.

Obviously, differences existed between the two movements, as they operated in different geographical settings and differed in their socio-political developmental stages.

But the anger and rage against remnants of Jim Crow and apartheid was visible in #BlackLivesMatter and #FeesMustFall.

- Social justice

- Nelson Mandela

- student activism

- #feesmustfall

- #BlackLivesMatter

- Peace and Security

- June 16 Uprisings

- President Barack Obama

- Jim Crow apartheid

Social Media Producer

Post Doctoral Research Fellow, Generative AI

Dean (Head of School), Indigenous Knowledges

Senior Research Fellow - Curtin Institute for Energy Transition (CIET)

Laboratory Head - RNA Biology

Advertisement

Supported by

Ramaphosa Gets Second Term in South Africa, but Coalition Is Fragile

A new government led by the African National Congress gave Cyril Ramaphosa another term as president, though he faces challenges in Parliament.

- Share full article

By John Eligon and Lynsey Chutel

Reporting from Cape Town and Johannesburg

A fragile coalition of lawmakers in South Africa elected Cyril Ramaphosa for a second term as president on Friday, marking a new era of political uncertainty in one of the continent’s most stable democracies.

After suffering a sharp decline in support in last month’s national election, Mr. Ramaphosa’s party, the African National Congress, undertook feverish negotiations to form a governing coalition with rivals, inking a deal only after Friday’s parliamentary session had begun.

The coalition deal includes the second-largest party, the Democratic Alliance — long a bitter rival of the A.N.C. — and the fifth-largest one, the Inkatha Freedom Party. Some of the 15 other parties in Parliament are also expected to join the coalition, which the A.N.C. is calling a “government of national unity.”

Many South Africans hope that this new coalition will force the parties to work together to provide better outcomes in a country with economic stagnation, high unemployment and entrenched poverty.

Addressing lawmakers after a 14-hour session, Mr. Ramaphosa said the fact that opposing parties decided to come together to elect him “has given a new birth, a new era to our country.”

“I do sincerely believe that this is an era of hope and is also an era of inclusivity,” he added.

The Democratic Alliance — which won nearly 22 percent of the vote — hailed the coalition agreement as a fresh start. “From today, the D.A. will co-govern the Republic of South Africa in a spirit of unity and collaboration,” said John Steenhuisen, the party’s leader.

We are having trouble retrieving the article content.

Please enable JavaScript in your browser settings.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access. If you are in Reader mode please exit and log into your Times account, or subscribe for all of The Times.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access.

Already a subscriber? Log in .

Want all of The Times? Subscribe .

Essay winners: Juneteenth lets us remember nation's past while striving for better future

Correction: Erin Mauldin is an associate professor at the University of South Florida. Her name was misspelled in an earlier version of this story.

Three 2024 high school graduates were honored this week as winners of the Juneteenth Scholarship essay contest. Their essays are below.

Juneteenth is chance to acknowledge both legacy and unfinished work

It is June 19, 1865, and over 250,000 enslaved Africans are gathered in Galveston, Texas, watching the United States Union Troops approach the bay to announce that after 400 years, they are free. Just a few months prior, Abraham Lincoln had announced the Emancipation Proclamation, freeing those enslaved in Confederate territory, but not all of them were made free.

This day is known as “Freedom Eve” or “Emancipation Day” and took place on January 1, 1865. The Emancipation Proclamation might not have cemented the actual liberation of African American people in the U.S., but it was a critical turning point that led up to the country’s second Independence Day, known as Juneteenth. Understanding what Juneteenth is and recognizing its importance and the intentions of other celebrations like it is essential.

Juneteenth, deriving from the words “June” and “Nineteenth”, is the day that marks the annual celebration of a huge step towards racial reckoning in the United States. Texas was the first state to make it a holiday in 1980, motivating other states to do the same in the years following. Finally, in 2021, Juneteenth became a national holiday. However, we must see this celebration as an obstacle that was overcome, rather than a destination. There is still much work to be done. Victories like this one encourage us to continue the fight.

Associate professor Erin Mauldin at the University of South Florida, an expert on civil war and reconstruction, talks about how “Juneteenth is neither the beginning nor the end of something.” The same article states that “the end of the Civil War and the ending of slavery didn't happen overnight and was a lot more like a jagged edge than a clean cut.” It is imperative to realize that the road ahead could be just as long as the road behind us.

In today’s age, the celebration of Juneteenth holds a higher significance than ever before, as we take time to honor the struggles endured but also acknowledge that many of those struggles are ongoing, as it pertains to racial inequality and systemic issues that create numerous disparities for African Americans. The historical injustices we suffered had only just begun to be accounted for by the rest of the country’s population. Juneteenth holds the purpose of reminding us of progress made thus far and is a chance for our community to move forward as a whole and help each other rebuild. This holiday gives millions of African Americans an opportunity to rejoice and give thanks to God for releasing them from years of suffering and captivity. The day creates a country-wide social awareness of the journey to equality and the abolishment of slavery’s awful oppression. Additionally, observing this day as a united front inspires self-development and is a chance to reconnect to one’s roots that were all but erased during slavery and go on to encourage African Americans to keep striving for a brighter future.

In France, Bastille Day acknowledges the fight and patience undergone to eventually reach freedom. July 14, 1880, is the day the citizens of France finally overcame King Louis XVI and his monarchy’s rule over them. Each year, they cherish this as a day of reclamation for their lives.

Every July 18th since 2010, the historical moment when Nelson Mandela became South Africa’s first black president, is recognized. This day is known as Mandela Day. Mandela transformed their democracy into a more diverse selection of administration, breaking down the white power held over the country for centuries. After being elected, he shared to his citizens this powerful message; “I have cherished the idea of a democratic and free society in which all persons live together in harmony and with equal opportunities.” Just as those countries continue to commemorate those momentous turning points in history, we must continue to honor Juneteenth’s significance.

Like Juneteenth, these important moments in history represent coming out on the other side of trials and tribulations, as well as salvaging their heritage. Universally, it is important to continue the recognition and cultivation of knowledge about Juneteenth and other celebrations akin to it, so we can mend communities back together who were violently ripped apart by domination subjugation. Breakthroughs didn’t happen without countless setbacks, but celebrations like these serve as a notion to never give up hope regardless. Juneteenth has the purpose and effect of uplifting hearts and minds to keep fighting, until justice and humanity are restored.

Hailey Perkins is co-winner of the Taylor Academic Talent Scholarship. She is a graduate of Okemos High School and will attend Howard University.

Celebrations of freedom offer history lessons

I imagine the words, “Ain’t nobody told me nothing!” came out of many mouths, minds and hearts when freed slaves found out they stayed in bondage 2 ½ years after other slaves had been set free. Slavery in Texas continued 900 hundred days after the Emancipation Proclamation was signed.

In I863, the Civil War was in its third year. Many lives had been lost, and the end was nowhere in sight. On January 1, 1863, President Lincoln enforced the signed Emancipation Proclamation. The Emancipation Proclamation stated, “That on the first day of January, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty-three, all persons held as slaves within any State or designated part of a State, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States, shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free.“

This proclamation freed slaves that were in states that had left the union. This proclamation could only be enforced if the North won the war. After continued fighting and the loss of many more lives, the Union won the war April 9, 1865. Then on June 19, 1865, in the state of Texas, more than 250,000 slaves were finally set free. Their freedom came 2 ½ years after everyone else’s. While gaining freedom was a dream come true, delayed freedom is symbolic of the continued struggle for Black Americans.

There are many opinions regarding the celebration of Juneteenth. Many people celebrate it as the end of slavery, others don’t celebrate it at all, while others fall somewhere in between. Although Juneteenth has been celebrated for many years, it was only in 2021 that it became a national holiday.

The importance of celebrating Juneteenth is because America needs to know. Celebrating Juneteenth provides the opportunity to educate and inform our communities. Celebrating this holiday is more than remembering the past but it gives an opportunity to discuss race relations today. It allows people to have difficult conversations about hard subjects. Ultimately, celebrating Juneteenth allows us to examine the mistakes of the past and do better in the future.

Celebrating this holiday makes us ask tough questions about the beginning of our country, our values, and our rights. Celebrating Juneteenth since the murder of George Floyd has made many people question, “Are Black people really free?”

Juneteenth celebrations are now opportunities to discuss systemic racism, policy change, politics and ways to make sure that our lives do matter. Most importantly, it forces us to take an honest look at race relations in America, ask how are we really doing?

There are many celebrations of freedom and independence across the world. India celebrates its freedom from British rule. Ghana celebrates its freedom from the United Kingdom. But the country whose freedom celebration identifies with me the most is the Philippines. My paternal grandfather’s wife is from the Philippines. She shared much about her birthplace and its culture with our family. The country celebrates its freedom from Spanish rule with a celebration called Araw ng Kalayaan.

The celebration is filled with parades, music, food and family bonding. But the Philippines has another celebration for freedom. After the Spanish rule ended, the Philippines came under the rule of America. But it was a nation that wanted to be free. The road to independence for the Philippines is similar to the Juneteenth celebration, and the delay in freedom. The Philippines nation was supposed to become independent in 1944. But World War II occurred and like Juneteenth that freedom was delayed for 2 full years.

On July 4, 1946, the Philippines became fully free from United States. Today, the citizens of the Philippines celebrate not one but 2 days of independence and freedom. A sign of their perseverance. These celebrations remind us to never give up.

It is vital to continue the celebration of Juneteenth and other cultural celebrations of freedom around the world because “knowledge is power.” These celebrations symbolize more than just freedom. They are evidence that major changes in society can happen despite the odds. They provide motivation for people to stand up for basic human rights and against injustice.

Most importantly these celebrations give us hope. They are evidence that we can be part of the change that we want to see in the world. When I think back to the first Juneteenth, that moment when the slaves realized they were enslaved 900 days longer than everyone else. That moment when they had to think, “Ain’t nobody told me nothing!”

Well today, I told you something. Never forget the lesson of Juneteenth or the other cultural celebrations of freedom.

Zachary Barker is co-winner of the Taylor Academic Talent Scholarship. He is a graduate of Okemos High School and will attend Michigan State University.

The importance of why we celebrate Juneteenth

Juneteenth, also known as Juneteenth Independence Day or Freedom Day, is an annual holiday recognized on June 19th in honor of the enslavement of oppressed African Americans in the United States. The festival started in Galveston, Texas, where on June 19, 1865, Union soldiers conveyed the news of the Emancipation Proclamation to the state's last surviving enslaved people, thereby ending slavery in the United States.

On January 1, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, which announced that all enslaved individuals in Confederate-held territory would be set free. However, it wasn't until the Civil War ended and Union forces landed in Texas that the word of freedom reached the remaining enslaved people. Understanding the history of Juneteenth is important, including its connection to other countries, the significance of learning about it as a child, and how it is celebrated today.

While Juneteenth is uniquely American, it bears shared characteristics with other cultural celebrations of liberty and independence across the world. Many countries have their own celebrations, which are cultural and historical events. For example, India celebrates its independence from British dominion on August 15th of each year, remembering the day in 1947 when the country gained freedom after years of struggle and sacrifice. Similarly, Mexico commemorates its independence from Spanish colonial rule on September 16th, often known as "El Grito de Dolores." These cultural celebrations of sovereignty and liberty contain common themes such as determination and the pursuit of justice. They remind us of the challenges that persecuted populations have experienced throughout history, as well as the significance of preserving and respecting their tales. By connecting Juneteenth to other cultural celebrations, we may get a more comprehensive understanding of their significance.

Juneteenth was recently given new attention and significance as a result of the ongoing battle for racial equality and social justice in the United States. The Black Lives Matter movement and rallies against police brutality have drawn attention to the systems of prejudice and inequality that persist in American society. As a result, recognizing and remembering Juneteenth has never been more crucial.

At the high school level, students ought to learn about and participate in cultural celebrations of freedom and independence, such as Juneteenth. By understanding the history and significance of these festivals, students may develop a better understanding of different individuals' perspectives as well as the continued effect of historical events on our modern society. Studying Juneteenth and other cultural festivals of independence allows students to critically assess problems of race, power, and privilege. By discussing the historical foundations of systematic racism and oppression, students may obtain a better understanding of social justice concerns and the need of speaking up against injustices in their own communities. Incorporating conversations and activities about cultural celebrations of freedom and independence into the curriculum for high school can help students extend their viewpoints and get a better grasp of the complexity of history and culture. These abilities are critical for creating a more inclusive and equitable society in which all people are respected, appreciated, and celebrated.

To summarize, Juneteenth's historical significance as a celebration of liberation and freedom for African Americans is firmly anchored in the history of slavery and the ongoing battle for equality and justice. By commemorating and celebrating Juneteenth, we recognize the significance of remembering history, comprehending the present, and working for a more fair and equitable future for everyone. Studying and recognizing these events in high school, students may get significant insights into the experiences of other groups, as well as the ongoing efforts for freedom and equality.

In today's world, when the fight for racial equality is ongoing, commemorating Juneteenth is more vital than ever, as it serves as an important awareness of the African American community's continued struggle for justice and perseverance.

Glorie Clay is the winner of the University of Olivet Academic Talent Scholarship. She is a graduate of Lansing Christian High School and will attend Olivet.

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

Most Black Americans Believe U.S. Institutions Were Designed To Hold Black People Back

2. black americans’ mistrust of the criminal justice system , table of contents.

- In their own words: Quotes from our 2023 focus groups of Black Americans

- Most Black adults say they experience racial discrimination

- Black adults feel angry or undermined in the face of discrimination

- Black adults say they must work more than everyone else to get ahead

- Black Americans believe the criminal justice system was designed to hold them back

- Black adults and mistrust about policing and prisons

- Many Black Americans believe the U.S. political system was designed to hold them back

- Black Americans, Black political leaders and mistrust of the U.S. political system

- Black Americans believe the economic system was designed to hold them back

- Mistrust of big businesses

- About half of Black Americans believe U.S. news media was designed to hold them back

- Most Black adults say they encounter inaccurate news about Black people

- Some Black Americans believe the health care system was designed to hold them back

- Mistrust about medical research

- Mistrust of family-related government policy

- Mistrust of government reproductive health policy

- Acknowledgments

- The American Trends Panel survey methodology

- Focus group methodology

Editorial note to readers

A version of this study was originally published on June 10. We previously used the term “ racial conspiracy theories ” as an editorial shorthand to describe a complex and mixed set of findings. By using these words, our reporting distorted rather than clarified the point of the study. Changes to this version include: an updated headline, new “explainer” paragraphs, some additional context and direct quotes from focus group participants.

Claudia Deane, Mark Hugo Lopez and Neha Sahgal contributed to the revision of this report.

Views about the intentions of the U.S. criminal justice system have their roots in key events in the 20th century.

In the convict-leasing and chain gang systems of the early 1900s, Black men were forced to build roads, bridges and ditches as part of their incarceration. This new infrastructure improved the business prospects of rural planters throughout the South.

And in the 1990s, the CIA released a report about its role in the inner-city cocaine epidemic of the 1980s and early ’90s. While the agency denied that it was directly involved, it admitted that addressing drug activity in their Central American operations was not among its priorities.

These events provide some context for Black Americans’ beliefs about the intentions of the nation’s criminal justice system.

About three-quarters (74%) of Black adults say the prison system was designed to hold Black people back a great deal or a fair amount. Similar shares say the same about the courts and judicial process (70%) and policing (68%). While many Black adults say the criminal justice system was designed to hold Black people back, there are some group differences.

By discrimination experience and ethnicity

Racial discrimination continues to be a significant factor in how Black Americans assess their progress, or lack of it. Those who have experienced racial discrimination are more likely than those who haven’t to say the prison system (79% vs. 62%), judicial process (74% vs. 61%) and policing (73% vs. 55%) each was designed to hold Black people back.

When it comes to ethnicity, the majority of non-Hispanic (75%) and multiracial (72%) Black adults say the prison system and the judicial process were designed to hold Black people back. Fewer Hispanic Black adults say the same (60%).

By education, family income and party

Black Americans’ views also differ by education. About three-quarters or more of Black adults who have been to college, regardless of their degree status, say the prison system, the judicial process and policing were designed to hold Black people back. Those with a high school diploma or less education are less likely to agree. Likewise, Black adults with high family incomes are more likely than those with lower family incomes to say the same about prisons and policing. 2

Political affiliation also plays a role in what Black adults believe about the criminal justice system. Black Democrats are more likely than Black Republicans, including those who lean to each party, to say the prison system (78% vs. 59%), judicial process (74% vs. 55%) and policing (72% vs. 54%) were intentionally designed to hold Black people back, though majorities of both groups say the systems were designed this way.

In addition to believing the criminal justice system was designed to hold Black people back, most Black Americans mistrust the criminal justice system.

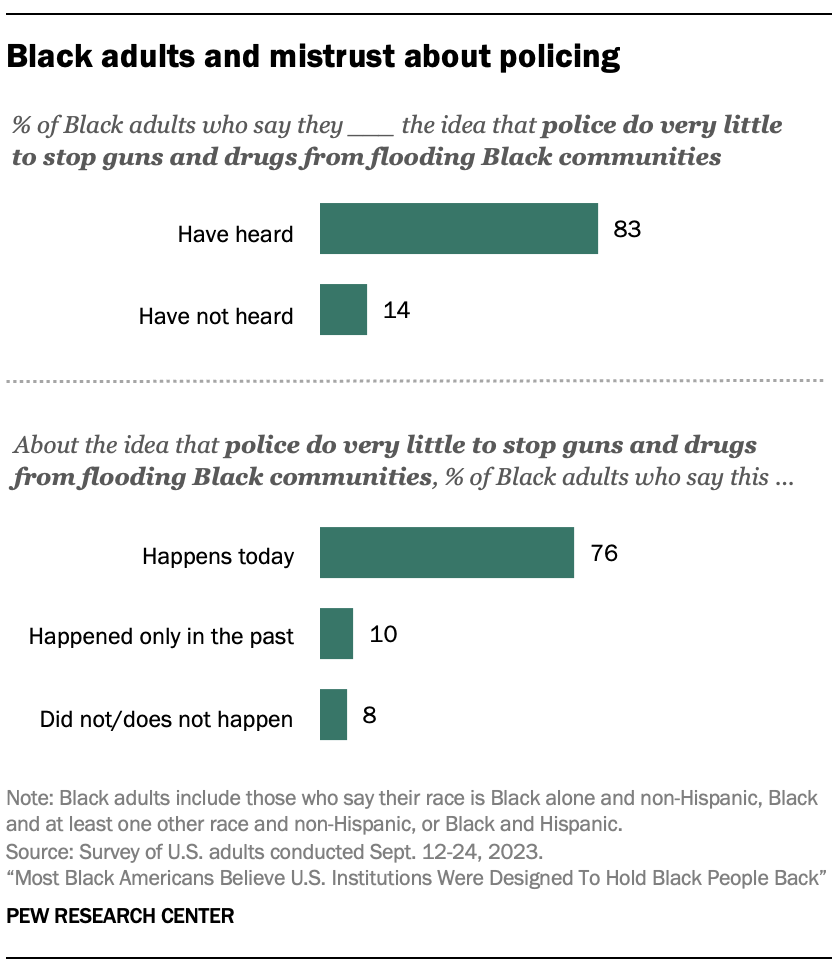

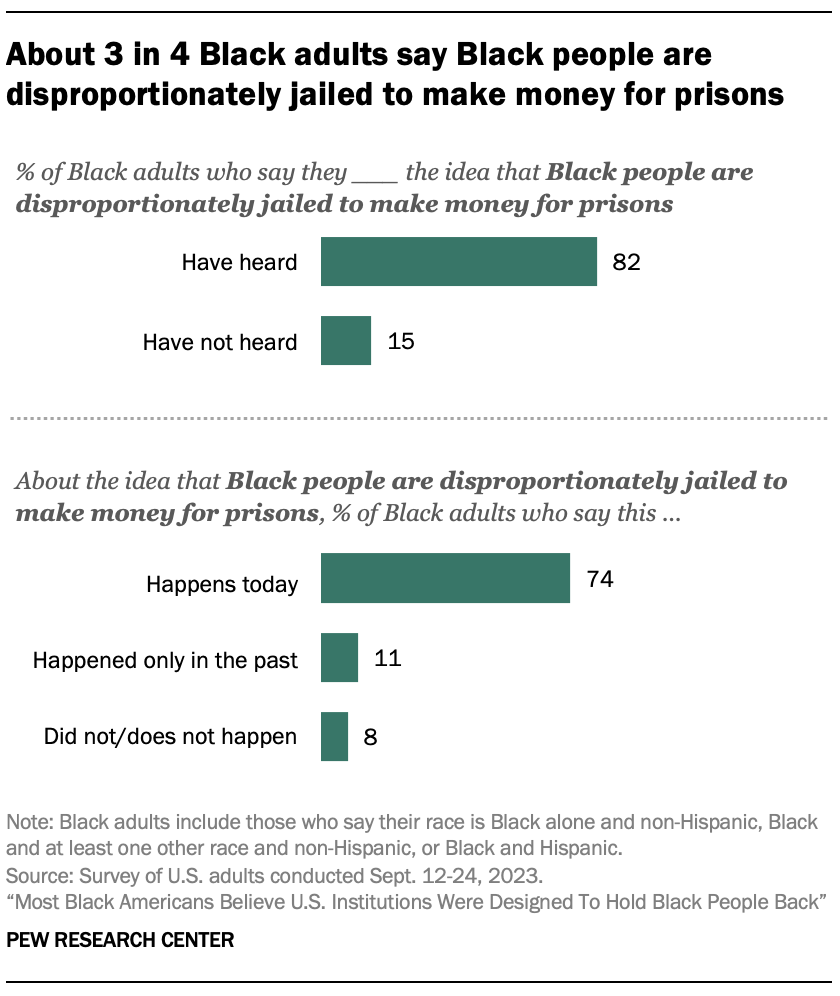

Some 83% of Black adults say they have heard of the idea that police do very little to prevent guns and drugs from flooding Black communities. And 82% have heard the idea that Black people are incarcerated more than White people to create profit for prisons. Only about 15% of Black Americans say they are unfamiliar with these narratives.

Beliefs about policing in Black communities

About three-quarters of Black adults say the police’s failure to prevent the flow of guns and drugs in Black communities is something that happens today (76%). By comparison, 10% say this happened in the past but no longer happens today, and 8% say this has never happened.

By discrimination experience and community type

Black adults who have experienced racial discrimination (80%) are more likely than those who haven’t (68%) to say the failure of police to prevent the flow of guns and drugs is something that happens today. And Black adults who live in urban areas (80%) are slightly more likely than those in suburbs (76%) or rural areas (72%) to say this.

By education and party

Black adults also differ on this question by education and political party. Those with a bachelor’s degree (78%) are more likely than those with a high school diploma or less (72%) to say that police are failing to prevent the flow of guns and drugs into Black communities. A larger share of Black Democrats (79%) believe this than among Black Republicans (66%), though majorities of both groups say this.

Beliefs about prisons and profits