Heuristics: Definition, Examples, And How They Work

Benjamin Frimodig

Science Expert

B.A., History and Science, Harvard University

Ben Frimodig is a 2021 graduate of Harvard College, where he studied the History of Science.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul McLeod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

On This Page:

Every day our brains must process and respond to thousands of problems, both large and small, at a moment’s notice. It might even be overwhelming to consider the sheer volume of complex problems we regularly face in need of a quick solution.

While one might wish there was time to methodically and thoughtfully evaluate the fine details of our everyday tasks, the cognitive demands of daily life often make such processing logistically impossible.

Therefore, the brain must develop reliable shortcuts to keep up with the stimulus-rich environments we inhabit. Psychologists refer to these efficient problem-solving techniques as heuristics.

Heuristics can be thought of as general cognitive frameworks humans rely on regularly to reach a solution quickly.

For example, if a student needs to decide what subject she will study at university, her intuition will likely be drawn toward the path that she envisions as most satisfying, practical, and interesting.

She may also think back on her strengths and weaknesses in secondary school or perhaps even write out a pros and cons list to facilitate her choice.

It’s important to note that these heuristics broadly apply to everyday problems, produce sound solutions, and helps simplify otherwise complicated mental tasks. These are the three defining features of a heuristic.

While the concept of heuristics dates back to Ancient Greece (the term is derived from the Greek word for “to discover”), most of the information known today on the subject comes from prominent twentieth-century social scientists.

Herbert Simon’s study of a notion he called “bounded rationality” focused on decision-making under restrictive cognitive conditions, such as limited time and information.

This concept of optimizing an inherently imperfect analysis frames the contemporary study of heuristics and leads many to credit Simon as a foundational figure in the field.

Kahneman’s Theory of Decision Making

The immense contributions of psychologist Daniel Kahneman to our understanding of cognitive problem-solving deserve special attention.

As context for his theory, Kahneman put forward the estimate that an individual makes around 35,000 decisions each day! To reach these resolutions, the mind relies on either “fast” or “slow” thinking.

The fast thinking pathway (system 1) operates mostly unconsciously and aims to reach reliable decisions with as minimal cognitive strain as possible.

While system 1 relies on broad observations and quick evaluative techniques (heuristics!), system 2 (slow thinking) requires conscious, continuous attention to carefully assess the details of a given problem and logically reach a solution.

Given the sheer volume of daily decisions, it’s no surprise that around 98% of problem-solving uses system 1.

Thus, it is crucial that the human mind develops a toolbox of effective, efficient heuristics to support this fast-thinking pathway.

Heuristics vs. Algorithms

Those who’ve studied the psychology of decision-making might notice similarities between heuristics and algorithms. However, remember that these are two distinct modes of cognition.

Heuristics are methods or strategies which often lead to problem solutions but are not guaranteed to succeed.

They can be distinguished from algorithms, which are methods or procedures that will always produce a solution sooner or later.

An algorithm is a step-by-step procedure that can be reliably used to solve a specific problem. While the concept of an algorithm is most commonly used in reference to technology and mathematics, our brains rely on algorithms every day to resolve issues (Kahneman, 2011).

The important thing to remember is that algorithms are a set of mental instructions unique to specific situations, while heuristics are general rules of thumb that can help the mind process and overcome various obstacles.

For example, if you are thoughtfully reading every line of this article, you are using an algorithm.

On the other hand, if you are quickly skimming each section for important information or perhaps focusing only on sections you don’t already understand, you are using a heuristic!

Why Heuristics Are Used

Heuristics usually occurs when one of five conditions is met (Pratkanis, 1989):

- When one is faced with too much information

- When the time to make a decision is limited

- When the decision to be made is unimportant

- When there is access to very little information to use in making the decision

- When an appropriate heuristic happens to come to mind at the same moment

When studying heuristics, keep in mind both the benefits and unavoidable drawbacks of their application. The ubiquity of these techniques in human society makes such weaknesses especially worthy of evaluation.

More specifically, in expediting decision-making processes, heuristics also predispose us to a number of cognitive biases .

A cognitive bias is an incorrect but pervasive judgment derived from an illogical pattern of cognition. In simple terms, a cognitive bias occurs when one internalizes a subjective perception as a reliable and objective truth.

Heuristics are reliable but imperfect; In the application of broad decision-making “shortcuts” to guide one’s response to specific situations, occasional errors are both inevitable and have the potential to catalyze persistent mistakes.

For example, consider the risks of faulty applications of the representative heuristic discussed above. While the technique encourages one to assign situations into broad categories based on superficial characteristics and one’s past experiences for the sake of cognitive expediency, such thinking is also the basis of stereotypes and discrimination.

In practice, these errors result in the disproportionate favoring of one group and/or the oppression of other groups within a given society.

Indeed, the most impactful research relating to heuristics often centers on the connection between them and systematic discrimination.

The tradeoff between thoughtful rationality and cognitive efficiency encompasses both the benefits and pitfalls of heuristics and represents a foundational concept in psychological research.

When learning about heuristics, keep in mind their relevance to all areas of human interaction. After all, the study of social psychology is intrinsically interdisciplinary.

Many of the most important studies on heuristics relate to flawed decision-making processes in high-stakes fields like law, medicine, and politics.

Researchers often draw on a distinct set of already established heuristics in their analysis. While dozens of unique heuristics have been observed, brief descriptions of those most central to the field are included below:

Availability Heuristic

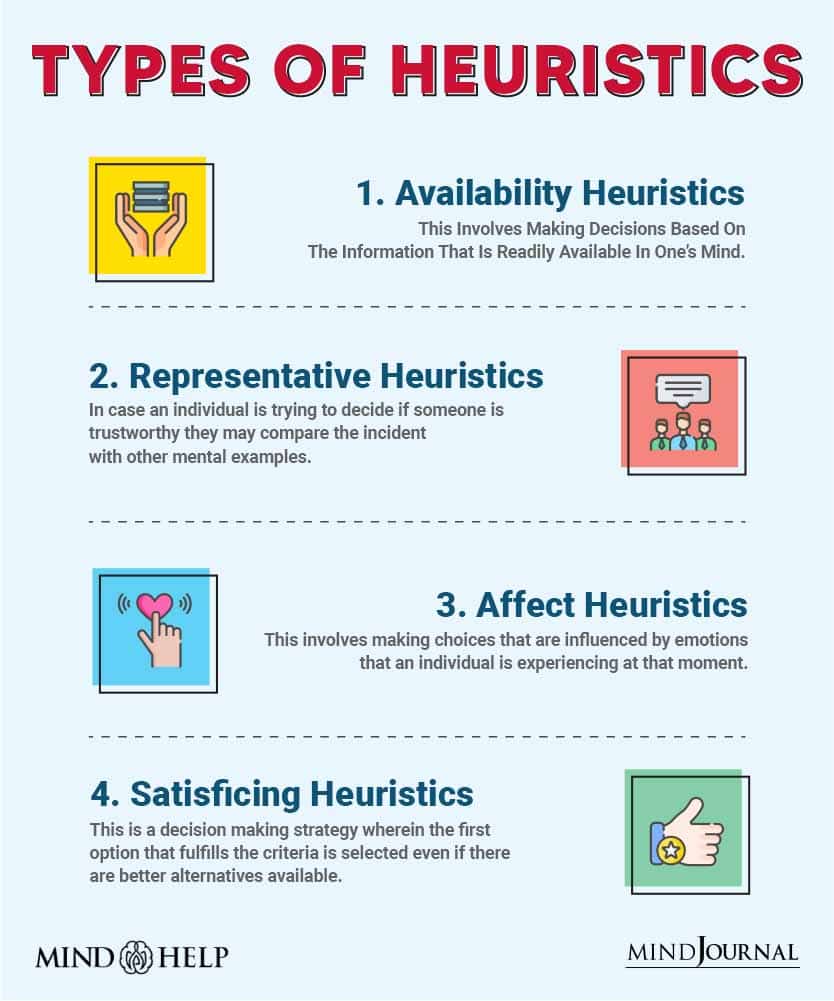

The availability heuristic describes the tendency to make choices based on information that comes to mind readily.

For example, children of divorced parents are more likely to have pessimistic views towards marriage as adults.

Of important note, this heuristic can also involve assigning more importance to more recently learned information, largely due to the easier recall of such information.

Representativeness Heuristic

This technique allows one to quickly assign probabilities to and predict the outcome of new scenarios using psychological prototypes derived from past experiences.

For example, juries are less likely to convict individuals who are well-groomed and wearing formal attire (under the assumption that stylish, well-kempt individuals typically do not commit crimes).

This is one of the most studied heuristics by social psychologists for its relevance to the development of stereotypes.

Scarcity Heuristic

This method of decision-making is predicated on the perception of less abundant, rarer items as inherently more valuable than more abundant items.

We rely on the scarcity heuristic when we must make a fast selection with incomplete information. For example, a student deciding between two universities may be drawn toward the option with the lower acceptance rate, assuming that this exclusivity indicates a more desirable experience.

The concept of scarcity is central to behavioral economists’ study of consumer behavior (a field that evaluates economics through the lens of human psychology).

Trial and Error

This is the most basic and perhaps frequently cited heuristic. Trial and error can be used to solve a problem that possesses a discrete number of possible solutions and involves simply attempting each possible option until the correct solution is identified.

For example, if an individual was putting together a jigsaw puzzle, he or she would try multiple pieces until locating a proper fit.

This technique is commonly taught in introductory psychology courses due to its simple representation of the central purpose of heuristics: the use of reliable problem-solving frameworks to reduce cognitive load.

Anchoring and Adjustment Heuristic

Anchoring refers to the tendency to formulate expectations relating to new scenarios relative to an already ingrained piece of information.

Put simply, this anchoring one to form reasonable estimations around uncertainties. For example, if asked to estimate the number of days in a year on Mars, many people would first call to mind the fact the Earth’s year is 365 days (the “anchor”) and adjust accordingly.

This tendency can also help explain the observation that ingrained information often hinders the learning of new information, a concept known as retroactive inhibition.

Familiarity Heuristic

This technique can be used to guide actions in cognitively demanding situations by simply reverting to previous behaviors successfully utilized under similar circumstances.

The familiarity heuristic is most useful in unfamiliar, stressful environments.

For example, a job seeker might recall behavioral standards in other high-stakes situations from her past (perhaps an important presentation at university) to guide her behavior in a job interview.

Many psychologists interpret this technique as a slightly more specific variation of the availability heuristic.

How to Make Better Decisions

Heuristics are ingrained cognitive processes utilized by all humans and can lead to various biases.

Both of these statements are established facts. However, this does not mean that the biases that heuristics produce are unavoidable. As the wide-ranging impacts of such biases on societal institutions have become a popular research topic, psychologists have emphasized techniques for reaching more sound, thoughtful and fair decisions in our daily lives.

Ironically, many of these techniques are themselves heuristics!

To focus on the key details of a given problem, one might create a mental list of explicit goals and values. To clearly identify the impacts of choice, one should imagine its impacts one year in the future and from the perspective of all parties involved.

Most importantly, one must gain a mindful understanding of the problem-solving techniques used by our minds and the common mistakes that result. Mindfulness of these flawed yet persistent pathways allows one to quickly identify and remedy the biases (or otherwise flawed thinking) they tend to create!

Further Information

- Shah, A. K., & Oppenheimer, D. M. (2008). Heuristics made easy: an effort-reduction framework. Psychological bulletin, 134(2), 207.

- Marewski, J. N., & Gigerenzer, G. (2012). Heuristic decision making in medicine. Dialogues in clinical neuroscience, 14(1), 77.

- Del Campo, C., Pauser, S., Steiner, E., & Vetschera, R. (2016). Decision making styles and the use of heuristics in decision making. Journal of Business Economics, 86(4), 389-412.

What is a heuristic in psychology?

A heuristic in psychology is a mental shortcut or rule of thumb that simplifies decision-making and problem-solving. Heuristics often speed up the process of finding a satisfactory solution, but they can also lead to cognitive biases.

Bobadilla-Suarez, S., & Love, B. C. (2017, May 29). Fast or Frugal, but Not Both: Decision Heuristics Under Time Pressure. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition .

Bowes, S. M., Ammirati, R. J., Costello, T. H., Basterfield, C., & Lilienfeld, S. O. (2020). Cognitive biases, heuristics, and logical fallacies in clinical practice: A brief field guide for practicing clinicians and supervisors. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 51 (5), 435–445.

Dietrich, C. (2010). “Decision Making: Factors that Influence Decision Making, Heuristics Used, and Decision Outcomes.” Inquiries Journal/Student Pulse, 2(02).

Groenewegen, A. (2021, September 1). Kahneman Fast and slow thinking: System 1 and 2 explained by Sue. SUE Behavioral Design. Retrieved March 26, 2022, from https://suebehaviouraldesign.com/kahneman-fast-slow-thinking/

Kahneman, D., Lovallo, D., & Sibony, O. (2011). Before you make that big decision .

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, fast and slow . Macmillan.

Pratkanis, A. (1989). The cognitive representation of attitudes. In A. R. Pratkanis, S. J. Breckler, & A. G. Greenwald (Eds.), Attitude structure and function (pp. 71–98). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Simon, H.A., 1956. Rational choice and the structure of the environment. Psychological Review .

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1974). Judgment under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases. Science, 185 (4157), 1124–1131.

Grab Your Free Copy of The State of Leadership Development Report 2024

Heuristic Problem Solving: A comprehensive guide with 5 Examples

What are heuristics, advantages of using heuristic problem solving, disadvantages of using heuristic problem solving, heuristic problem solving examples, frequently asked questions.

- Speed: Heuristics are designed to find solutions quickly, saving time in problem solving tasks. Rather than spending a lot of time analyzing every possible solution, heuristics help to narrow down the options and focus on the most promising ones.

- Flexibility: Heuristics are not rigid, step-by-step procedures. They allow for flexibility and creativity in problem solving, leading to innovative solutions. They encourage thinking outside the box and can generate unexpected and valuable ideas.

- Simplicity: Heuristics are often easy to understand and apply, making them accessible to anyone regardless of their expertise or background. They don’t require specialized knowledge or training, which means they can be used in various contexts and by different people.

- Cost-effective: Because heuristics are simple and efficient, they can save time, money, and effort in finding solutions. They also don’t require expensive software or equipment, making them a cost-effective approach to problem solving.

- Real-world applicability: Heuristics are often based on practical experience and knowledge, making them relevant to real-world situations. They can help solve complex, messy, or ill-defined problems where other problem solving methods may not be practical.

- Potential for errors: Heuristic problem solving relies on generalizations and assumptions, which may lead to errors or incorrect conclusions. This is especially true if the heuristic is not based on a solid understanding of the problem or the underlying principles.

- Limited scope: Heuristic problem solving may only consider a limited number of potential solutions and may not identify the most optimal or effective solution.

- Lack of creativity: Heuristic problem solving may rely on pre-existing solutions or approaches, limiting creativity and innovation in problem-solving.

- Over-reliance: Heuristic problem solving may lead to over-reliance on a specific approach or heuristic, which can be problematic if the heuristic is flawed or ineffective.

- Lack of transparency: Heuristic problem solving may not be transparent or explainable, as the decision-making process may not be explicitly articulated or understood.

- Trial and error: This heuristic involves trying different solutions to a problem and learning from mistakes until a successful solution is found. A software developer encountering a bug in their code may try other solutions and test each one until they find the one that solves the issue.

- Working backward: This heuristic involves starting at the goal and then figuring out what steps are needed to reach that goal. For example, a project manager may begin by setting a project deadline and then work backward to determine the necessary steps and deadlines for each team member to ensure the project is completed on time.

- Breaking a problem into smaller parts: This heuristic involves breaking down a complex problem into smaller, more manageable pieces that can be tackled individually. For example, an HR manager tasked with implementing a new employee benefits program may break the project into smaller parts, such as researching options, getting quotes from vendors, and communicating the unique benefits to employees.

- Using analogies: This heuristic involves finding similarities between a current problem and a similar problem that has been solved before and using the solution to the previous issue to help solve the current one. For example, a salesperson struggling to close a deal may use an analogy to a successful sales pitch they made to help guide their approach to the current pitch.

- Simplifying the problem: This heuristic involves simplifying a complex problem by ignoring details that are not necessary for solving it. This allows the problem solver to focus on the most critical aspects of the problem. For example, a customer service representative dealing with a complex issue may simplify it by breaking it down into smaller components and addressing them individually rather than simultaneously trying to solve the entire problem.

Test your problem-solving skills for free in just a few minutes.

The free problem-solving skills for managers and team leaders helps you understand mistakes that hold you back.

What are the three types of heuristics?

What are the four stages of heuristics in problem solving.

Other Related Blogs

Top 15 Tips for Effective Conflict Mediation at Work

Top 10 games for negotiation skills to make you a better leader, manager effectiveness: a complete guide for managers in 2024, 5 proven ways managers can build collaboration in a team.

22 Heuristics Examples (The Types of Heuristics)

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

Learn about our Editorial Process

A heuristic is a mental shortcut that enables people to make quick but less-than-optimal decisions.

The benefit of heuristics is that they allow us to make fast decisions based upon approximations, fast cognitive strategies, and educated guesses. The downside is that they often lead us to come to inaccurate conclusions and make flawed decisions.

The most common examples of heuristics are the availability, representativeness, and affect heuristics. However, there are many more possible examples, as shown in the 23 listed below.

Heuristics Definition

Psychologists Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman created the concept of heuristics in the early 1970s. They can be described in the following way:

“[They are] judgmental shortcuts that generally get us where we need to go – and quickly – but at the cost of occasionally sending us off course.”

Thus, we can see heuristics as being both positive and negative for our lives. But most interestingly, they can be leveraged in marketing situations to manipulate people’s purchasing decisions, as discussed below.

Types of Heuristics with Examples

1. availability heuristic.

Quick Definition: Making decisions based upon information that is easily available.

We often rely upon and place greater emphasis upon information that is easily available when making decisions.

We might make a decision based solely on what we know about a topic rather than conducting deeper research in order to make a more informed decision. This causes mistakes in our thinking and leads us to make decisions that are flawed or not sufficiently thought out.

This bias is one reason why political parties try to be the last person who talks to a voter before they go into a polling booth. The newness of the information may cause someone to vote for that part because the party’s arguments are closest to the top of mind.

> Check out these 15 availability heuristic examples

2. Representativeness Heuristic

Quick Definition: Making judgments based upon the similarity of one thing to its archetype. In social situations, this leads to prejudice.

We often make a snap judgment about something by placing it into a category based on its surface appearance. For example, we might see a tree and immediately assume it’s in the oak family based upon the color of its bark or size of its leaves.

In social sciences, we can also see that people make judgements about other people based upon their race, gender, class, or other aspects of their identity. In these situations, we are using stereotypes to come to snap judgements about others.

In these situations, our stereotypical assumptions about others can lead to bias, prejudice , and even discrimination .

> Check out these 11 representativeness heuristic examples

3. Affect Heuristic

Quick Definition: We often make decisions based on emotions, moods, and “gut feelings” rather than logic.

Emotions, moods, and feelings impact our thoughts. This simple fact can lead people into making emotional decisions that they may regret later on when they reflect using logic.

One affect heuristic example is the fact that we often make emotional outbursts that we regret later on. Yelling at a cashier at the shops, for example, may be followed up with regret when we reflect and realize it really wasn’t the cashier’s fault.

Similarly, shoppers make impulse purchases based on the feelings they have about the handbag or new dress. These purchases may be regretted later on when we use logic and realize we have overspent our budgets.

4. Anchoring Heuristic

Quick Definition: We often make decisions based upon a subjective anchoring point that influences all subsequent thinking on a topic.

An anchoring point is often the original piece of information that we are given. Based upon this original piece of information, all future thinking and decisions look good or bad.

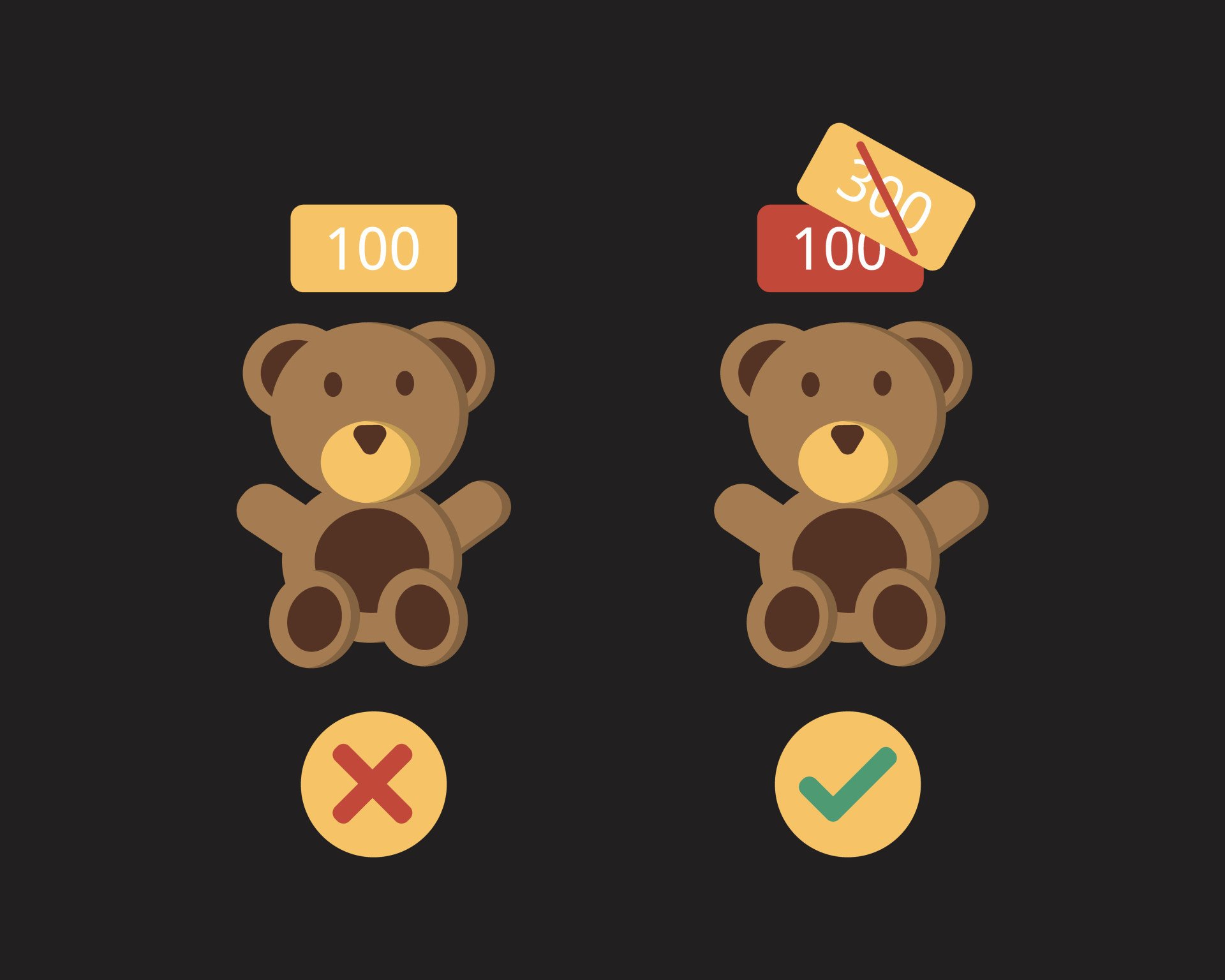

An anchoring heuristic example is when a company sets the cost of their goods high before setting a discount. If a high price is set, then a discount is applied, then people would see the price as a bargain rather than high .

Similarly, if you were looking at two highly-priced products, the product that is a few dollars less than the other is seen as a good deal, even if its price is also inflated.

5. Base Rate Heuristic

Quick Definition: We neglect the base statistics in favor of other more proximate statistics when making a judgment.

Base rate neglect occurs when someone forgets the base rate, or a basic fact about information, and instead makes decisions based upon other information that they place too much importance upon.

For example, we may predict that the next person to walk into a hospital is a man if the last three people who entered were all males.

This assumption neglects the fact that 50% of all people who enter hospitals are women.

Here, we are privileging immediate information: that there appears to be a lot of men entering the hospital right now., instead of the base rate fact: that you’ve generally got a 50% chance of a woman walking into the store.

6. Absurdity Heuristic

Quick Definition: We tend to classify things that are improbably as absurd rather than giving them proper consideration.

Many people who believe themselves to be highly logical fall prey to the absurdity heuristic. This occurs when you hear a claim that is improbable, so you instantly dismiss it out of hand.

The ability to filter out absurdity has been highly useful to humans – allowing us to keep our focus on reality and not get caught up in conspiracy theories day and night.

But this becomes a problem when we dismiss things that are serious problems. For example, rejection of climate change science based on the fact that it seems extreme, or a doctor dismissing symptoms of a rare disease, are cases when absurdity bias leads us to make overly dismissive decisions.

7. Contagion Heuristic

Quick Definition: We can sometimes see people, ideas, and things as being either positively or negatively contagious despite lack of logic.

Sometimes, people will try to avoid contact with something or someone that has been the victim of bad luck. For example, a person may feel uncomfortable touching a cancer patient despite the fact they are not at all contagious.

On the positive end, we may believe lucky people will remain lucky and may even spread good luck if we spend time with them. Sometimes, this could be called the halo effect and horns effect.

8. Effort Heuristic

Quick Definition: Assuming the quality of something correlates with the amount of effort put into it.

We will often think something is more valuable or higher quality if it took a great deal of effort to create it. This assumption may be correct, but it doesn’t always turn out to be true.

For example, a person may spend 20 hours a day, 365 days a year, working on a startup business and it may still fail due to flaws in the business model. Another person may build a business in a week and see instant success.

Here, there is no positive correlation between effort and quality.

Nevertheless, the effort heuristic is utilized by advertisers all the time. Advertisements might talk about the amount of hours spent testing products, the research and development money put into it, and so on, in order to show that a lot of effort was put into it. The insinuation here is that the effort has led to a higher-quality product, when this is not necessarily always true.

9. Familiarity Heuristic

Quick Definition: We can often take mental shortcuts where we decide things that are most familiar to us are better than things that are less familiar.

Humans tend to see safety in the familiar and risk in the unfamiliar. In reality, familiar things may be just as risky, if not more, than unfamiliar things. Nevertheless, we know how to navigate familiar situations and therefore find them less risky.

A good example of this is travel. We may look to a country overseas and see it as potentially dangerous or scary. But, looking at data, our hometown or home city may be far more dangerous!

Similarly, we’re much more likely to die in a car crash than a plane crash. Nevertheless, fear may overcome you getting on a plane despite the fact that you didn’t put a moment’s thought into the drive to the airport.

10. Fluency Heuristic

Quick Definition: If an idea is communicated more fluently or skillfully then it is given more credence than an idea that is clumsily communicated, regardless of the merit of the idea.

The fluency with which an idea is communicated can directly impact how we perceive the idea. This mental shortcut allows us to bypass direct assessment of the merits of a case. Instead, we rely more on the charisma of the communicator.

For example, leaders with charismatic authority can often command a high vote during elections because of their ability to connect with voters moreso than their actual policy positions.

11. Gaze Heuristic

Quick Definition: Animals and humans have developed the ability to fixate on an estimated position rather than conducting complex calculations. Generally, this is in relation to motion.

The most common example of the gaze heuristic is the process humans go through to estimate where a ball will land. We don’t do all the calculations to understand trajectory and angle. Instead, we’ve developed an uncanny ability to identify where the ball will land through mental shortcuts based on previous experience.

Similarly, predatory animals can predict where their prey will flee to in order to intercept it, bats can use it during echolocation to estimate the location of obstacles, and hockey goalkeepers can use it to estimate the eventual position of a puck flying towards the goals.

12. Recognition Heuristic

Quick Definition: We assume that things we recognize have more value than things we do not recognize.

Recognition is an important facet of product marketing. Brand recognition alone can help a brand to thrive among a field of other products on a shelf.

The recognition heuristic states that we take mental shortcuts when looking at a range of options by assuming that the most recognizable option holds greater value. Thus, we assume a well-known household brand is higher-quality than a lesser-known brand.

Similarly, a study in psychology found that people assume cities whose names they recognize have larger populations than those that they don’t recognize. This assumption is based on the mental shortcut that larger cities are more likely to have recognizable names than smaller cities. This mental shortcut is often accurate, showing how heuristics can be beneficial (we call this the “less is more effect”).

13. Scarcity Heuristic

Quick Definition: When something is scarce , we see it as more valuable.

False scarcity is a widely-utilized method in marketing psychology because it encourages consumers to see a product as having greater value than it really does.

When a product is framed as being scarce, it is seen as having value because only a certain number of people can have it. As a result, people want it more. Sometimes, we call this the framing effect .

One way marketers use false scarcity is that they create limited-time discounts. In this case, the low price is a point of scarcity. Another way they can create false scarcity is to have open and closed cart periods so the product is only available for a short period of time.

This is a heuristic because people are encouraged to bypass making cold contemplative decisions about the product and, instead, make rushed decisions based on fear of missing out.

14. Similarity Heuristic

Quick Definition: Similarity between past and present situations impacts decision-making, allowing people to bypass making objective comparisons of two alternatives.

We tend to rely on past experiences to shape future experiences. If we liked something previously, then we may seek out similar situations in the future. If we didn’t like it in the past ,then we may avoid those situations in the future.

This logic allows people to bypass a thorough assessment of something and, instead, make fast decisions based on past experience.

Marketers can take advantage of this tendency. For example, a new fast food restaurant may use colors and a menu similar to McDonald;s in order to lull consumers into seeing the restaurant as similar to their previous positive experiences at McDonald’s, and therefore more likely to give it a go.

Similarly, Netflix may show you shows and movies similar to previous ones you watched to the end, because Netflix knows that you are going to be partisan toward a similar experience to the ones you previously enjoyed.

15. Simulation Heuristic

Quick Definition: We tend to overestimate the likelihood of an event based upon how easy it is to visualize it.

If our minds are able to visualize something happening, then we overstimate its probability.

Generally, the simulation heuristic occurs in relation to regret or near misses. A great example of this is buying a lottery ticket. If you found out that someone bought a winning lottery ticket one hour after you bought your ticket, then you’d easily be able to visualize the potentiality that you had gotten stuck in traffic that day and turned up to buy the ticket an hour later.

In this example, the probability of you ever turning up to buy the lottery ticket at the right time and place remains extremely low. However, because you can so easily visualize that eventuality, it feels as if you were truly very close to winning the lottery.

16. Social Proof Heuristic

Quick Definition: We use social proof as a mental shortcut to verify the quality or veracity of something instead of investigating it ourselves.

The social proof heuristic occurs both in social norms and product marketing.

In social norms, people tend to accept something as normal, correct, or appropriate because the rest of society does.

We could imagine, for example, 200 years ago many people thought the idea of the women’s right to vote as an idea that is strange or worthy of serious critique before being implemented. There weren’t many people supportive of the idea, so it was unquestioned. Today, because women’s right to vote is a social norm, it seems absurd that anyone would take it away.

In both of the above situations, people relied on broader society’s views (i.e. social proof) as an anchoring point for their own thinking on the topic.

Similarly, in marketing, marketers often go to great lengths to get quotes from “average joes” who have used a product in order to provide social proof in their advertisements.

17. Authority Heuristic

Quick Definition: We tend to defer to authorities as a shortcut rather than doing the thinking and research ourselves.

Society is structured in such a way that we defer to authorities and experts constantly. For example, we will defer to doctors on medical issues, engineers when building bridges, and lawyers on legal issues.

It’s just impossible to go about life trying to be an expert and authority on every topic. Instead, we will need to team up with authorities to make intelligent decisions. So, this heuristic is necessary.

However, mistakes can often be made when we see a person as an authority in one topic and, therefore, assume they’re an authority in entirely unrelated topics.

18. Hot-Hand Fallacy

Quick Definition: We overestimate our chances of success after a string of recent successes.

The hot-hand fallacy assumes that successful people will continue to experience success in the future.

The phrase “hot-hand” refers to gambling where a person rolling a dice has a “hot-hand” if they keep rolling the right numbers.

But we can apply this concept to a range of other situations. For example, we can apply it to investment funds, where investors will invest in a fund if it recently saw a lot of success.

However, past success does not guarantee future results. The more important thing would be to look at their investment philosophy rather than take the mental shortcut of “if they have recently been successful, then they will be in the future, too.”

19. Occam’s Razor

Quick Definition: The assumption that the most straightforward explanation is the most accurate.

Occam’s razor refers to the preferencing of more straightforward explanations as opposed to more complex ones. One logical justification for this is that the straightforward explanation has the least possible variables where mistakes in logic can occur.

However, critics of this approach highlight that, by definition, Occam’s razor fails to contemplate all possible variables and therefore causes oversimplification of explanations. Nevertheless, invoking Occam’s razor allows people to step back from a situation and contemplate whether they have over-complicated a simple situation.

>Check out these 15 occam’s razor examples

20. Naive Diversification

Quick Definition: Longer-term planning tends to involve more diversification than shorter-term planning.

Consider a situation where you are asked to purchase 5 weeks’ worth of groceries at once. In this situation, you’re more likely to buy a diverse range of fruit and vegetables for the forthcoming five weeks.

By contrast, if you were to go shopping once a week for five weeks, you’re less likely to diversify. Rather, you would buy a narrow range of products that you want in the short term.

In this example, people tend to diversify when faced with longer-term plans than shorter-term plans.

Naive diversification teaches us a lesson in business and investment. It teaches us that sometimes we are too soon to diversify when making plans because of our inability to make longer-term decisions in the shorter-term. As a result, we try to hedge by diversifying.

21. Peak–End Rule

Quick Definition: People tend to remember and pass judgment on an event based upon its most intense moment of finality rather than the average.

The peak-end rule refers to situations where the peak and end of a situation are the most important in our memories. When describing situations in the past tense, our minds shortcut to the peak and the end and fail to contemplate the other parts of the memory.

For example, a book or movie may be boring for 75% of the film, but the last 25% are excellent. You then go away and tell people how excellent it was, forgetting that there were long boring periods.

This is because our minds are most stimulated at the highly emotive parts of a situation, searing them in our memories.

This rule can be applied in vacation packages, movies, and other experince-based services where the experience is curated so the peak (and end) are highly stimulating to create a ‘wow experience’ that shapes people’s memories.

22. Mere Exposure Effect

Quick Definition: The mere exposure effect occurs when people develop a preference for a stimulus (such as a brand) simply because it is familiar. It is sometimes referred to as the familiarity principle.

The more frequently a person sees, experiences, or is otherwise exposed to something, the more likely it is that they will begin to like and favor it.

This is a cognitive heuristic because it involves a mental shortcut where something that is familiar is assumed to be safer and more trustworthy than unfamiliar things, regardless of the facts of the case.

This is used extensively in advertising, for example, where repeated exposure to advertisements from a particular brand, such as a restaurant, might make people more inclined to go to that restaurant next time they are hungry.

>See our full article on the Mere Exposure Effect

Heuristics are rules of thumb that help us make decisions quickly. They are useful in many situations, and in fact have helped us evolutionarily by filtering out bad information and making decisions quickly.

However, they can can also lead to biases and errors in our thinking. In the worst-case scenarios they can lead to stereotyping and significant social harm. The most common types of heuristics are availability heuristics, representativeness heuristics, and anchoring and adjustment.

Knowing about these biases in our thinking can help marketers to sell products and help reflective people to make better decisions by knowing when and when not to use heuristics.

See Also: Fundamental Attribution Error Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 10 Reasons you’re Perpetually Single

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 20 Montessori Toddler Bedrooms (Design Inspiration)

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 21 Montessori Homeschool Setups

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 101 Hidden Talents Examples

2 thoughts on “22 Heuristics Examples (The Types of Heuristics)”

Really interesting reading about the types of Heuristics and thank you for the concise explanations.

The information was very concise is used it for a presentation I had. Thank you

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

What Are Heuristics?

These mental shortcuts lead to fast decisions—and biased thinking

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Steven Gans, MD is board-certified in psychiatry and is an active supervisor, teacher, and mentor at Massachusetts General Hospital.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/steven-gans-1000-51582b7f23b6462f8713961deb74959f.jpg)

Verywell / Cindy Chung

- History and Origins

- Heuristics vs. Algorithms

- Heuristics and Bias

How to Make Better Decisions

If you need to make a quick decision, there's a good chance you'll rely on a heuristic to come up with a speedy solution. Heuristics are mental shortcuts that allow people to solve problems and make judgments quickly and efficiently. Common types of heuristics rely on availability, representativeness, familiarity, anchoring effects, mood, scarcity, and trial-and-error.

Think of these as mental "rule-of-thumb" strategies that shorten decision-making time. Such shortcuts allow us to function without constantly stopping to think about our next course of action.

However, heuristics have both benefits and drawbacks. These strategies can be handy in many situations but can also lead to cognitive biases . Becoming aware of this might help you make better and more accurate decisions.

Press Play for Advice On Making Decisions

Hosted by therapist Amy Morin, LCSW, this episode of The Verywell Mind Podcast shares a simple way to make a tough decision. Click below to listen now.

Follow Now : Apple Podcasts / Spotify / Google Podcasts

History of the Research on Heuristics

Nobel-prize winning economist and cognitive psychologist Herbert Simon originally introduced the concept of heuristics in psychology in the 1950s. He suggested that while people strive to make rational choices, human judgment is subject to cognitive limitations. Purely rational decisions would involve weighing every alternative's potential costs and possible benefits.

However, people are limited by the amount of time they have to make a choice and the amount of information they have at their disposal. Other factors, such as overall intelligence and accuracy of perceptions, also influence the decision-making process.

In the 1970s, psychologists Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman presented their research on cognitive biases. They proposed that these biases influence how people think and make judgments.

Because of these limitations, we must rely on mental shortcuts to help us make sense of the world.

Simon's research demonstrated that humans were limited in their ability to make rational decisions, but it was Tversky and Kahneman's work that introduced the study of heuristics and the specific ways of thinking that people rely on to simplify the decision-making process.

How Heuristics Are Used

Heuristics play important roles in both problem-solving and decision-making , as we often turn to these mental shortcuts when we need a quick solution.

Here are a few different theories from psychologists about why we rely on heuristics.

- Attribute substitution : People substitute simpler but related questions in place of more complex and difficult questions.

- Effort reduction : People use heuristics as a type of cognitive laziness to reduce the mental effort required to make choices and decisions.

- Fast and frugal : People use heuristics because they can be fast and correct in certain contexts. Some theories argue that heuristics are actually more accurate than they are biased.

In order to cope with the tremendous amount of information we encounter and to speed up the decision-making process, our brains rely on these mental strategies to simplify things so we don't have to spend endless amounts of time analyzing every detail.

You probably make hundreds or even thousands of decisions every day. What should you have for breakfast? What should you wear today? Should you drive or take the bus? Fortunately, heuristics allow you to make such decisions with relative ease and without a great deal of agonizing.

There are many heuristics examples in everyday life. When trying to decide if you should drive or ride the bus to work, for instance, you might remember that there is road construction along the bus route. You realize that this might slow the bus and cause you to be late for work. So you leave earlier and drive to work on an alternate route.

Heuristics allow you to think through the possible outcomes quickly and arrive at a solution.

Are Heuristics Good or Bad?

Heuristics aren't inherently good or bad, but there are pros and cons to using them to make decisions. While they can help us figure out a solution to a problem faster, they can also lead to inaccurate judgments about others or situations. Understanding these pros and cons may help you better use heuristics to make better decisions.

Types of Heuristics

There are many different kinds of heuristics. While each type plays a role in decision-making, they occur during different contexts. Understanding the types can help you better understand which one you are using and when.

Availability

The availability heuristic involves making decisions based upon how easy it is to bring something to mind. When you are trying to make a decision, you might quickly remember a number of relevant examples.

Since these are more readily available in your memory, you will likely judge these outcomes as being more common or frequently occurring.

For example, imagine you are planning to fly somewhere on vacation. As you are preparing for your trip, you might start to think of a number of recent airline accidents. You might feel like air travel is too dangerous and decide to travel by car instead. Because those examples of air disasters came to mind so easily, the availability heuristic leads you to think that plane crashes are more common than they really are.

Familiarity

The familiarity heuristic refers to how people tend to have more favorable opinions of things, people, or places they've experienced before as opposed to new ones. In fact, given two options, people may choose something they're more familiar with even if the new option provides more benefits.

Representativeness

The representativeness heuristic involves making a decision by comparing the present situation to the most representative mental prototype. When you are trying to decide if someone is trustworthy, you might compare aspects of the individual to other mental examples you hold.

A soft-spoken older woman might remind you of your grandmother, so you might immediately assume she is kind, gentle, and trustworthy. However, this is an example of a heuristic bias, as you can't know someone trustworthy based on their age alone.

The affect heuristic involves making choices that are influenced by an individual's emotions at that moment. For example, research has shown that people are more likely to see decisions as having benefits and lower risks when in a positive mood.

Negative emotions, on the other hand, lead people to focus on the potential downsides of a decision rather than the possible benefits.

The anchoring bias involves the tendency to be overly influenced by the first bit of information we hear or learn. This can make it more difficult to consider other factors and lead to poor choices. For example, anchoring bias can influence how much you are willing to pay for something, causing you to jump at the first offer without shopping around for a better deal.

Scarcity is a heuristic principle in which we view things that are scarce or less available to us as inherently more valuable. Marketers often use the scarcity heuristic to influence people to buy certain products. This is why you'll often see signs that advertise "limited time only," or that tell you to "get yours while supplies last."

Trial and Error

Trial and error is another type of heuristic in which people use a number of different strategies to solve something until they find what works. Examples of this type of heuristic are evident in everyday life.

People use trial and error when playing video games, finding the fastest driving route to work, or learning to ride a bike (or any new skill).

Difference Between Heuristics and Algorithms

Though the terms are often confused, heuristics and algorithms are two distinct terms in psychology.

Algorithms are step-by-step instructions that lead to predictable, reliable outcomes, whereas heuristics are mental shortcuts that are basically best guesses. Algorithms always lead to accurate outcomes, whereas, heuristics do not.

Examples of algorithms include instructions for how to put together a piece of furniture or a recipe for cooking a certain dish. Health professionals also create algorithms or processes to follow in order to determine what type of treatment to use on a patient.

How Heuristics Can Lead to Bias

Heuristics can certainly help us solve problems and speed up our decision-making process, but that doesn't mean they are always a good thing. They can also introduce errors, bias, and irrational decision-making. As in the examples above, heuristics can lead to inaccurate judgments about how commonly things occur and how representative certain things may be.

Just because something has worked in the past does not mean that it will work again, and relying on a heuristic can make it difficult to see alternative solutions or come up with new ideas.

Heuristics can also contribute to stereotypes and prejudice . Because people use mental shortcuts to classify and categorize people, they often overlook more relevant information and create stereotyped categorizations that are not in tune with reality.

While heuristics can be a useful tool, there are ways you can improve your decision-making and avoid cognitive bias at the same time.

We are more likely to make an error in judgment if we are trying to make a decision quickly or are under pressure to do so. Taking a little more time to make a decision can help you see things more clearly—and make better choices.

Whenever possible, take a few deep breaths and do something to distract yourself from the decision at hand. When you return to it, you may find a fresh perspective or notice something you didn't before.

Identify the Goal

We tend to focus automatically on what works for us and make decisions that serve our best interest. But take a moment to know what you're trying to achieve. Consider some of the following questions:

- Are there other people who will be affected by this decision?

- What's best for them?

- Is there a common goal that can be achieved that will serve all parties?

Thinking through these questions can help you figure out your goals and the impact that these decisions may have.

Process Your Emotions

Fast decision-making is often influenced by emotions from past experiences that bubble to the surface. Anger, sadness, love, and other powerful feelings can sometimes lead us to decisions we might not otherwise make.

Is your decision based on facts or emotions? While emotions can be helpful, they may affect decisions in a negative way if they prevent us from seeing the full picture.

Recognize All-or-Nothing Thinking

When making a decision, it's a common tendency to believe you have to pick a single, well-defined path, and there's no going back. In reality, this often isn't the case.

Sometimes there are compromises involving two choices, or a third or fourth option that we didn't even think of at first. Try to recognize the nuances and possibilities of all choices involved, instead of using all-or-nothing thinking .

Heuristics are common and often useful. We need this type of decision-making strategy to help reduce cognitive load and speed up many of the small, everyday choices we must make as we live, work, and interact with others.

But it pays to remember that heuristics can also be flawed and lead to irrational choices if we rely too heavily on them. If you are making a big decision, give yourself a little extra time to consider your options and try to consider the situation from someone else's perspective. Thinking things through a bit instead of relying on your mental shortcuts can help ensure you're making the right choice.

Vlaev I. Local choices: Rationality and the contextuality of decision-making . Brain Sci . 2018;8(1):8. doi:10.3390/brainsci8010008

Hjeij M, Vilks A. A brief history of heuristics: how did research on heuristics evolve? Humanit Soc Sci Commun . 2023;10(1):64. doi:10.1057/s41599-023-01542-z

Brighton H, Gigerenzer G. Homo heuristicus: Less-is-more effects in adaptive cognition . Malays J Med Sci . 2012;19(4):6-16.

Schwartz PH. Comparative risk: Good or bad heuristic? Am J Bioeth . 2016;16(5):20-22. doi:10.1080/15265161.2016.1159765

Schwikert SR, Curran T. Familiarity and recollection in heuristic decision making . J Exp Psychol Gen . 2014;143(6):2341-2365. doi:10.1037/xge0000024

AlKhars M, Evangelopoulos N, Pavur R, Kulkarni S. Cognitive biases resulting from the representativeness heuristic in operations management: an experimental investigation . Psychol Res Behav Manag . 2019;12:263-276. doi:10.2147/PRBM.S193092

Finucane M, Alhakami A, Slovic P, Johnson S. The affect heuristic in judgments of risks and benefits . J Behav Decis Mak . 2000; 13(1):1-17. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-0771(200001/03)13:1<1::AID-BDM333>3.0.CO;2-S

Teovanović P. Individual differences in anchoring effect: Evidence for the role of insufficient adjustment . Eur J Psychol . 2019;15(1):8-24. doi:10.5964/ejop.v15i1.1691

Cheung TT, Kroese FM, Fennis BM, De Ridder DT. Put a limit on it: The protective effects of scarcity heuristics when self-control is low . Health Psychol Open . 2015;2(2):2055102915615046. doi:10.1177/2055102915615046

Mohr H, Zwosta K, Markovic D, Bitzer S, Wolfensteller U, Ruge H. Deterministic response strategies in a trial-and-error learning task . Inman C, ed. PLoS Comput Biol. 2018;14(11):e1006621. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1006621

Grote T, Berens P. On the ethics of algorithmic decision-making in healthcare . J Med Ethics . 2020;46(3):205-211. doi:10.1136/medethics-2019-105586

Bigler RS, Clark C. The inherence heuristic: A key theoretical addition to understanding social stereotyping and prejudice. Behav Brain Sci . 2014;37(5):483-4. doi:10.1017/S0140525X1300366X

del Campo C, Pauser S, Steiner E, et al. Decision making styles and the use of heuristics in decision making . J Bus Econ. 2016;86:389–412. doi:10.1007/s11573-016-0811-y

Marewski JN, Gigerenzer G. Heuristic decision making in medicine . Dialogues Clin Neurosci . 2012;14(1):77-89. doi:10.31887/DCNS.2012.14.1/jmarewski

Zheng Y, Yang Z, Jin C, Qi Y, Liu X. The influence of emotion on fairness-related decision making: A critical review of theories and evidence . Front Psychol . 2017;8:1592. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01592

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

Reviewed by Psychology Today Staff

A heuristic is a mental shortcut that allows an individual to make a decision, pass judgment, or solve a problem quickly and with minimal mental effort. While heuristics can reduce the burden of decision-making and free up limited cognitive resources, they can also be costly when they lead individuals to miss critical information or act on unjust biases.

- Understanding Heuristics

- Different Heuristics

- Problems with Heuristics

As humans move throughout the world, they must process large amounts of information and make many choices with limited amounts of time. When information is missing, or an immediate decision is necessary, heuristics act as “rules of thumb” that guide behavior down the most efficient pathway.

Heuristics are not unique to humans; animals use heuristics that, though less complex, also serve to simplify decision-making and reduce cognitive load.

Generally, yes. Navigating day-to-day life requires everyone to make countless small decisions within a limited timeframe. Heuristics can help individuals save time and mental energy, freeing up cognitive resources for more complex planning and problem-solving endeavors.

The human brain and all its processes—including heuristics— developed over millions of years of evolution . Since mental shortcuts save both cognitive energy and time, they likely provided an advantage to those who relied on them.

Heuristics that were helpful to early humans may not be universally beneficial today . The familiarity heuristic, for example—in which the familiar is preferred over the unknown—could steer early humans toward foods or people that were safe, but may trigger anxiety or unfair biases in modern times.

The study of heuristics was developed by renowned psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky. Starting in the 1970s, Kahneman and Tversky identified several different kinds of heuristics, most notably the availability heuristic and the anchoring heuristic.

Since then, researchers have continued their work and identified many different kinds of heuristics, including:

Familiarity heuristic

Fundamental attribution error

Representativeness heuristic

Satisficing

The anchoring heuristic, or anchoring bias , occurs when someone relies more heavily on the first piece of information learned when making a choice, even if it's not the most relevant. In such cases, anchoring is likely to steer individuals wrong .

The availability heuristic describes the mental shortcut in which someone estimates whether something is likely to occur based on how readily examples come to mind . People tend to overestimate the probability of plane crashes, homicides, and shark attacks, for instance, because examples of such events are easily remembered.

People who make use of the representativeness heuristic categorize objects (or other people) based on how similar they are to known entities —assuming someone described as "quiet" is more likely to be a librarian than a politician, for instance.

Satisficing is a decision-making strategy in which the first option that satisfies certain criteria is selected , even if other, better options may exist.

Heuristics, while useful, are imperfect; if relied on too heavily, they can result in incorrect judgments or cognitive biases. Some are more likely to steer people wrong than others.

Assuming, for example, that child abductions are common because they’re frequently reported on the news—an example of the availability heuristic—may trigger unnecessary fear or overprotective parenting practices. Understanding commonly unhelpful heuristics, and identifying situations where they could affect behavior, may help individuals avoid such mental pitfalls.

Sometimes called the attribution effect or correspondence bias, the term describes a tendency to attribute others’ behavior primarily to internal factors—like personality or character— while attributing one’s own behavior more to external or situational factors .

If one person steps on the foot of another in a crowded elevator, the victim may attribute it to carelessness. If, on the other hand, they themselves step on another’s foot, they may be more likely to attribute the mistake to being jostled by someone else .

Listen to your gut, but don’t rely on it . Think through major problems methodically—by making a list of pros and cons, for instance, or consulting with people you trust. Make extra time to think through tasks where snap decisions could cause significant problems, such as catching an important flight.

Many apps claim to use nudges but instead use simple reminders that are just re-labeled as nudges. The terminology matters—true nudges use more potent behavioral science.

When you make a mistake for the third time, it's probably about you, not the situation.

The myth of the perfect question, the "fit" fallacy, and more.

Your plans should not be set based on the wisdom shared by successful people. They should be based on your context, your strengths, and your creative inspiration from that wisdom.

Discover how the anchoring effect, a subtle cognitive bias, shapes our decisions across life's domains.

Artificial intelligence already plays a role in deciding who’s getting hired. The way to improve AI is very similar to how we fight human biases.

Think you are avoiding the motherhood penalty by not having children? Think again. Simply being a woman of childbearing age can trigger discrimination.

Psychological experiments on human judgment under uncertainty showed that people often stray from presumptions about rational economic agents.

Are experts more confident in what they know than what they don't? Yes, but it's not so clear-cut.

Psychology, like other disciplines, uses the scientific method to acquire knowledge and uncover truths—but we still ask experts for information and rely on intuition. Here's why.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

It’s increasingly common for someone to be diagnosed with a condition such as ADHD or autism as an adult. A diagnosis often brings relief, but it can also come with as many questions as answers.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

7.3 Problem Solving

Learning objectives.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe problem solving strategies

- Define algorithm and heuristic

- Explain some common roadblocks to effective problem solving and decision making

People face problems every day—usually, multiple problems throughout the day. Sometimes these problems are straightforward: To double a recipe for pizza dough, for example, all that is required is that each ingredient in the recipe be doubled. Sometimes, however, the problems we encounter are more complex. For example, say you have a work deadline, and you must mail a printed copy of a report to your supervisor by the end of the business day. The report is time-sensitive and must be sent overnight. You finished the report last night, but your printer will not work today. What should you do? First, you need to identify the problem and then apply a strategy for solving the problem.

Problem-Solving Strategies

When you are presented with a problem—whether it is a complex mathematical problem or a broken printer, how do you solve it? Before finding a solution to the problem, the problem must first be clearly identified. After that, one of many problem solving strategies can be applied, hopefully resulting in a solution.

A problem-solving strategy is a plan of action used to find a solution. Different strategies have different action plans associated with them ( Table 7.2 ). For example, a well-known strategy is trial and error . The old adage, “If at first you don’t succeed, try, try again” describes trial and error. In terms of your broken printer, you could try checking the ink levels, and if that doesn’t work, you could check to make sure the paper tray isn’t jammed. Or maybe the printer isn’t actually connected to your laptop. When using trial and error, you would continue to try different solutions until you solved your problem. Although trial and error is not typically one of the most time-efficient strategies, it is a commonly used one.

Another type of strategy is an algorithm. An algorithm is a problem-solving formula that provides you with step-by-step instructions used to achieve a desired outcome (Kahneman, 2011). You can think of an algorithm as a recipe with highly detailed instructions that produce the same result every time they are performed. Algorithms are used frequently in our everyday lives, especially in computer science. When you run a search on the Internet, search engines like Google use algorithms to decide which entries will appear first in your list of results. Facebook also uses algorithms to decide which posts to display on your newsfeed. Can you identify other situations in which algorithms are used?

A heuristic is another type of problem solving strategy. While an algorithm must be followed exactly to produce a correct result, a heuristic is a general problem-solving framework (Tversky & Kahneman, 1974). You can think of these as mental shortcuts that are used to solve problems. A “rule of thumb” is an example of a heuristic. Such a rule saves the person time and energy when making a decision, but despite its time-saving characteristics, it is not always the best method for making a rational decision. Different types of heuristics are used in different types of situations, but the impulse to use a heuristic occurs when one of five conditions is met (Pratkanis, 1989):

- When one is faced with too much information

- When the time to make a decision is limited

- When the decision to be made is unimportant

- When there is access to very little information to use in making the decision

- When an appropriate heuristic happens to come to mind in the same moment

Working backwards is a useful heuristic in which you begin solving the problem by focusing on the end result. Consider this example: You live in Washington, D.C. and have been invited to a wedding at 4 PM on Saturday in Philadelphia. Knowing that Interstate 95 tends to back up any day of the week, you need to plan your route and time your departure accordingly. If you want to be at the wedding service by 3:30 PM, and it takes 2.5 hours to get to Philadelphia without traffic, what time should you leave your house? You use the working backwards heuristic to plan the events of your day on a regular basis, probably without even thinking about it.

Another useful heuristic is the practice of accomplishing a large goal or task by breaking it into a series of smaller steps. Students often use this common method to complete a large research project or long essay for school. For example, students typically brainstorm, develop a thesis or main topic, research the chosen topic, organize their information into an outline, write a rough draft, revise and edit the rough draft, develop a final draft, organize the references list, and proofread their work before turning in the project. The large task becomes less overwhelming when it is broken down into a series of small steps.

Everyday Connection

Solving puzzles.

Problem-solving abilities can improve with practice. Many people challenge themselves every day with puzzles and other mental exercises to sharpen their problem-solving skills. Sudoku puzzles appear daily in most newspapers. Typically, a sudoku puzzle is a 9×9 grid. The simple sudoku below ( Figure 7.7 ) is a 4×4 grid. To solve the puzzle, fill in the empty boxes with a single digit: 1, 2, 3, or 4. Here are the rules: The numbers must total 10 in each bolded box, each row, and each column; however, each digit can only appear once in a bolded box, row, and column. Time yourself as you solve this puzzle and compare your time with a classmate.

Here is another popular type of puzzle ( Figure 7.8 ) that challenges your spatial reasoning skills. Connect all nine dots with four connecting straight lines without lifting your pencil from the paper:

Take a look at the “Puzzling Scales” logic puzzle below ( Figure 7.9 ). Sam Loyd, a well-known puzzle master, created and refined countless puzzles throughout his lifetime (Cyclopedia of Puzzles, n.d.).

Pitfalls to Problem Solving

Not all problems are successfully solved, however. What challenges stop us from successfully solving a problem? Imagine a person in a room that has four doorways. One doorway that has always been open in the past is now locked. The person, accustomed to exiting the room by that particular doorway, keeps trying to get out through the same doorway even though the other three doorways are open. The person is stuck—but they just need to go to another doorway, instead of trying to get out through the locked doorway. A mental set is where you persist in approaching a problem in a way that has worked in the past but is clearly not working now.

Functional fixedness is a type of mental set where you cannot perceive an object being used for something other than what it was designed for. Duncker (1945) conducted foundational research on functional fixedness. He created an experiment in which participants were given a candle, a book of matches, and a box of thumbtacks. They were instructed to use those items to attach the candle to the wall so that it did not drip wax onto the table below. Participants had to use functional fixedness to overcome the problem ( Figure 7.10 ). During the Apollo 13 mission to the moon, NASA engineers at Mission Control had to overcome functional fixedness to save the lives of the astronauts aboard the spacecraft. An explosion in a module of the spacecraft damaged multiple systems. The astronauts were in danger of being poisoned by rising levels of carbon dioxide because of problems with the carbon dioxide filters. The engineers found a way for the astronauts to use spare plastic bags, tape, and air hoses to create a makeshift air filter, which saved the lives of the astronauts.

Link to Learning

Check out this Apollo 13 scene about NASA engineers overcoming functional fixedness to learn more.

Researchers have investigated whether functional fixedness is affected by culture. In one experiment, individuals from the Shuar group in Ecuador were asked to use an object for a purpose other than that for which the object was originally intended. For example, the participants were told a story about a bear and a rabbit that were separated by a river and asked to select among various objects, including a spoon, a cup, erasers, and so on, to help the animals. The spoon was the only object long enough to span the imaginary river, but if the spoon was presented in a way that reflected its normal usage, it took participants longer to choose the spoon to solve the problem. (German & Barrett, 2005). The researchers wanted to know if exposure to highly specialized tools, as occurs with individuals in industrialized nations, affects their ability to transcend functional fixedness. It was determined that functional fixedness is experienced in both industrialized and nonindustrialized cultures (German & Barrett, 2005).

In order to make good decisions, we use our knowledge and our reasoning. Often, this knowledge and reasoning is sound and solid. Sometimes, however, we are swayed by biases or by others manipulating a situation. For example, let’s say you and three friends wanted to rent a house and had a combined target budget of $1,600. The realtor shows you only very run-down houses for $1,600 and then shows you a very nice house for $2,000. Might you ask each person to pay more in rent to get the $2,000 home? Why would the realtor show you the run-down houses and the nice house? The realtor may be challenging your anchoring bias. An anchoring bias occurs when you focus on one piece of information when making a decision or solving a problem. In this case, you’re so focused on the amount of money you are willing to spend that you may not recognize what kinds of houses are available at that price point.

The confirmation bias is the tendency to focus on information that confirms your existing beliefs. For example, if you think that your professor is not very nice, you notice all of the instances of rude behavior exhibited by the professor while ignoring the countless pleasant interactions he is involved in on a daily basis. Hindsight bias leads you to believe that the event you just experienced was predictable, even though it really wasn’t. In other words, you knew all along that things would turn out the way they did. Representative bias describes a faulty way of thinking, in which you unintentionally stereotype someone or something; for example, you may assume that your professors spend their free time reading books and engaging in intellectual conversation, because the idea of them spending their time playing volleyball or visiting an amusement park does not fit in with your stereotypes of professors.

Finally, the availability heuristic is a heuristic in which you make a decision based on an example, information, or recent experience that is that readily available to you, even though it may not be the best example to inform your decision . Biases tend to “preserve that which is already established—to maintain our preexisting knowledge, beliefs, attitudes, and hypotheses” (Aronson, 1995; Kahneman, 2011). These biases are summarized in Table 7.3 .

Watch this teacher-made music video about cognitive biases to learn more.

Were you able to determine how many marbles are needed to balance the scales in Figure 7.9 ? You need nine. Were you able to solve the problems in Figure 7.7 and Figure 7.8 ? Here are the answers ( Figure 7.11 ).

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/1-introduction

- Authors: Rose M. Spielman, William J. Jenkins, Marilyn D. Lovett

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Psychology 2e

- Publication date: Apr 22, 2020

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/1-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/7-3-problem-solving

© Sep 19, 2024 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

Heuristics are mental shortcut techniques used to solve problems and make decisions efficiently. These techniques are used to reduce the decision making time and allow the individual to function without interrupting their next course of action.

What Is Heuristics?

Heuristics are a time-saving approach to solving problems and making decisions efficiently. Heuristics processes are usually used to find quick answers and solutions to problems. However, decisions based on this mindset are not always accurate. They serve as quick mental references that are used for everyday problems and experiences.

Humans and animals resort to this mindset because processing every information that comes into the brain takes time and effort. With the help of these shortcut techniques, the brain can make faster and efficient decisions despite the consequences. This is known as the accuracy effort trade-off theory. This theory works because not every decision requires the same amount of time and energy.

Hence, people use it as a means to save time. Another reason why people resort to heuristics is that the brain simply doesn’t have the capacity to process everything and so they must resort to these mental shortcuts to make quick decisions. A 2014 study [mfn] Mousavi, S., & Gigerenzer, G. (2014). Risk, uncertainty, and heuristics. Journal of Business Research , 67 (8), 1671-1678. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2014.02.013 [/mfn] demonstrated that in case of uncertainty and a lack of information, heuristics allows a “less is more effect” wherein less information leads to more accuracy. It is worth mentioning that the applicability and usefulness of heuristics depend on the situation.

A 2011 study [mfn] Gigerenzer G, Gaissmaier W. Heuristic decision making. Annu Rev Psychol. 2011;62:451-82. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-120709-145346. PMID: 21126183. [/mfn] pointed out that there may be two reasons for relying on heuristics. They are:

- Individuals and organizations often rely on simple heuristics in an adaptive way