Brief History of Music: An Introduction

In all probability, music has played an important role in the lifecycle of humans perhaps even before we could speak. Significant evidence has been discovered that very early man developed primitive flutes from animal bones and used stones and wood as percussion.

Voice would have been the first and most natural means of expression in our distant ancestors, used to bond socially or comfort a sleepless child. It is from these humble beginnings that the music we enjoy today evolved.

As we move further through the history of music we find increasing evidence of its key role in sacred and secular settings, although the division into these categories was not defined in this way until many years later.

History of Music

Influences from the west to the east merged into the pre-Christian music of the Greeks and later the Romans. Musical practices and conventions perhaps conveyed by travelling musicians brought a wealth of diversity and invention.

Surviving Greek notation from this period of musical history has given scientists and musicologists alike a vital clue to the way that the music of the time might have sounded. It certainly indicates remarkable links to the music that would follow, perhaps most notably through the use of modality in Greek music.

In the frescoes and in some written accounts, including the Bible, we have learned about the instruments that featured in the Roman and Greek times and their significance to the cultures. The trumpet as an instrument of announcement and splendid ceremony, or the lyre as an integral player in the songs of poets.

Across Europe from the early part of the first century, the monasteries and abbeys became the places where music became embedded into the lives of those devoted to God and their followers.

Christianity had established itself and with it came a new liturgy that demanded a new music. Although early Christian music had its roots in the practices and beliefs of the Hebrew people, what emerged from this was to become the basis for sacred music for centuries to come. The chants that were composed devoutly followed the sacred Latin texts in a fashion that was tightly controlled and given only to the glory of God. Music was very much subservient to the words, without flourish or frivolity.

It was Pope Gregory (540-604 AD), who is credited with moving the progress of sacred music forward and developing what is now called Gregorian Chant, characterises by the haunting sound of the open, perfect fifth.

Some controversy surrounds this claim, but the name has stuck and the music remains distinct and vitally important as it moves away from plainchant towards polyphony. This, in turn, looked back to earlier times and customs, particularly in the music of the Jewish people where the idea of a static drone commonly underpinned a second vocal line.

Medieval Period

As we move forward in musical time, we begin to enter the Medieval Period of music which can be generally agreed to span the period from around 500AD up until the mid-fifteenth century. By this time music was a dominant art in taverns to cathedrals, practised by kings to paupers alike. It was during this extended period of music that the sound of music becomes increasingly familiar. This is partly due to the development of musical notation, much of which has survived, that allows us a window back into this fascinating time.

From the written music that survives from the monasteries and other important accounts of musical practices, it’s possible to assemble an image of a vibrant culture that ranges from the sacred to the secular. Throughout the Medieval period, the music slowly began to adopt ever more elaborate structures and devices that produced works of immense beauty and devotion.

Hildegard von Bingen and Perotin pioneered many of the musical forms we still recognise today including the motet and the sacred Mass. Alongside these important forms came the madrigal that often reflects the moods and feelings of the people of the time. It’s wonderfully polyphonic form is both mesmerising and delightful.

Renaissance Period

Instruments developed in accordance with the composer’s imaginations. A full gamut of wind, brass and percussion instruments accompanied the Medieval music, although it is still the human voice that dominates many of the compositions. Towards the close of the high medieval period, we find the emergence of instrumental pieces in their own right which in turn paves the way for many musical forms in the following period: The Renaissance .

Before leaving this period of music it is important to mention the Troubadours and the Trouveres. These travelling storytellers and musicians covered vast distances on their journeys across Europe and further afield into Asia. They told stories, sung ballads and perhaps most importantly, brought with them influences from far and wide that seamlessly blended with the western musical cultures.

The Renaissance (1450 – 1600) was a golden period in music history. Freed from the constraints of Medieval musical conventions the composers of the Renaissance forged a new way forward. Josquin des Prez is considered to be one of the early Renaissance composers to be a great master of the polyphonic style, often combining many voices to create elaborate musical textures.

Later Palestrina, Thomas Tallis and William Byrd build on the ideas of des Pres composing some of the most stunning motets, masses, chansons and instrumental works in their own right. Modality was firmly established as a basis for all harmony, and although strict rules governing the use of dissonance, the expressive qualities of Renaissance music is virtually unparalleled.

As instrumental pieces became accepted into the repertoire, we find the development of instruments like the bassoon and the trombone giving rise to larger and more elaborate instrumental groupings.

This gave composers far more scope to explore and express their creative ideas than before. The viol family developed to provide a very particular, haunted quality to much of the music of the time alongside the establishment of each recognisable family of instruments comprising, percussion, strings, woodwind and brass.

Keyboard instruments also became increasingly common and the advent of the sonata followed in due course. Other popular forms for instrumental music included the toccata, canzona and ricercar to name but a few, emanating from the Courtly dance.

Towards the end of the Renaissance, what was called the Church Modes began to dissolve in favour of what is now considered to be functional harmony or tonality based on a system of keys rather than modes.

Baroque Period

The Baroque Period (1600-1760), houses some of the most famous composers and pieces that we have in Western Classical Music. It also sees some of the most important musical and instrumental developments. Italy, Germany, England and France continue from the Renaissance to dominate the musical landscape, each influencing the other with conventions and style.

Amongst the many celebrated composers of the time, G F Handel, Bach, Vivaldi and Purcell provide a substantial introduction to the music of this era. It is during this glittering span of time that Handel composes his oratorio “The Messiah”, Vivaldi the “Four Seasons”, Bach his six “Brandenburg Concertos” and the “48 Preludes and Fugues”, together with Purcell’s opera “Dido and Aeneas”.

Instrumental music was composed and performed in tandem with vocal works, each of equal importance in the Baroque. The virtuosity that began amongst the elite Renaissance performers flourished in the Baroque. Consider the keyboard Sonatas of Domenico Scarlatti or the Concertos that Vivaldi composed for his student performers. This, in turn, leads to significant instrumental developments, and thanks to the aristocratic support of Catherine Medici, the birth of the Violin.

Common musical forms were established founded on the Renaissance composers principles but extended and developed in ways that they would have probably found unimaginable. The Suite became a Baroque favourite, comprising contrasting fast slow movements like the Prelude; Allemande, Gigue, Courante and the Sarabande. Concertos became ever more popular, giving instrumentalists the opportunity to display their technical and expressive powers.

Vocal music continued to include the Mass but now also the Oratorio and Cantata alongside anthems and chorales. Opera appears in earnest in the Baroque period and becomes an established musical form and vehicle for astonishing expression and diversity.

Increasingly, the preferred harmony is tonal and the system of keys (major and minor), is accepted in favour of modality. This lifts the limitations of modes and offers composers the chance to create ever more complex and expressive pieces that combine exciting polyphonic textures and dynamics.

Notation accompanies these developments and steadily we find that the accuracy of composers works becomes more precise and detailed giving us a better possibility of realising their intentions in performances of today.

Classical Period

From the Baroque, we step into the Classical Period (1730-1820). Here Haydn and Mozart dominate the musical landscape and Germany and Austria sit at the creative heart of the period. From the ornate Baroque composers of the Classical period moved away from the polyphonic towards the homophonic, writing music that was, on the surface of it at least, simple, sleek and measured.

One key development is that of the Piano. The Baroque harpsichord is replaced by the early piano which was a more reliable and expressive instrument. Mozart and Haydn each wrote a large number of works for the Piano which allowed for this instrument to develop significantly during this period.

Chamber music alongside orchestral music was a feature of the Classical Era with particular attention drawn towards the String Quartet. The orchestra itself was firmly established and towards the latter end of the period began to include clarinets, trombones, and timpani.

The rise of the virtuoso performer continued throughout this period of music as demonstrated by the many of the concertos and sonatas composed during this time. Opera flourished in these decades and became a fully-fledged musical form of entertainment that extended way beyond the dreams of the Baroque composers.

Romantic Period

As the Classical era closed Beethoven is the most notable composer who made such a huge contribution to the change into the Romantic Era (1780 – 1880). Beethoven’s immense genius shaped the next few decades with his substantial redefining of many of the established musical conventions of the Classical era. His work on Sonata form in his concertos, symphonies, string quartets and sonatas, goes almost unmatched by any other composer.

The Romantic era saw huge developments in the quality and range of many instruments that naturally encouraged ever more expressive and diverse music from the composers. Musical forms like the Romantic orchestra became expansive landscapes where composers gave full and unbridled reign to their deepest emotions and dreams.

Berlioz in his “Symphonie Fantastique” is a fine example of this, or later Wagner in his immense operas. The symphonies of Gustav Mahler stand like stone pillars of achievement at the end of the Romantic period alongside the tone poems of Richard Strauss. The Romantic period presents us with a vast array of rich music that only towards the end of the 19 th Century began to fade.

It is hard to conceive of what could follow such a triumphant, heroic time in musical history but as we push forward into the 20 th Century the musical landscape takes a dramatic turn. Echoes of the Romantic Era still thread through the next century in the works of Elgar, Shostakovich and Arthur Bliss, but it is the music from France we have title impressionism that sparkles its way into our musical consciences.

Debussy and Ravel are key exponents of this colourful movement that parallels the artwork of Monet and Manet. What we hear in the music of the impressionists harks back to many of the popular forms of the Baroque but in ways that Bach is unlikely to have foreseen. The tonal system transforms to include a wider range of scales and influences from the Orient allowing composers to write some of the most stunning works ever heard.

Both Ravel and Debussy composed extensively for the piano using poetry for inspiration. Their orchestral works are amongst some of the most beautiful and evocative pieces ever written.

In parallel, the Teutonic world began to undergo its own revolution in the form of the second Viennese school, led by Arnold Schoenberg. Disillusioned with the confines of tonality Schoenberg threw out the tonal system in favour of a new twelve-tone serial system giving each step of the chromatic scale equal musical validity. The result was serial music that was completely atonal and transformed the musical landscape almost beyond anything that had happened before.

Read: Brief History of Classical Music Periods

4 thoughts on “Brief History of Music: An Introduction”

This is great piece. What I wonder the Greek Scholars who invented the G clef and C Clef with tone of Letters A-G and 5 lines. They say it happened in late BC

I adored this text. Thank you for the informations. The music is the better art humankind ever did. It is a pleasure to know people don’t yet let the classics die.

Isn’t this more of a history of western art music then Music

There are mainly six periods of music and each period has a particular style. Music is an expression of feelings, emotions through specific sounds. We listen to music everywhere like in the singing of birds, whistling of a person and impressive sounds by a live band. All these are the simplest form of music. Thanks for sharing the information.

Leave a Comment

HYPOTHESIS AND THEORY article

How music and instruments began: a brief overview of the origin and entire development of music, from its earliest stages.

- University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom

Music must first be defined and distinguished from speech, and from animal and bird cries. We discuss the stages of hominid anatomy that permit music to be perceived and created, with the likelihood of both Homo neanderthalensis and Homo sapiens both being capable. The earlier hominid ability to emit sounds of variable pitch with some meaning shows that music at its simplest level must have predated speech. The possibilities of anthropoid motor impulse suggest that rhythm may have preceded melody, though full control of rhythm may well not have come any earlier than the perception of music above. There are four evident purposes for music: dance, ritual, entertainment personal, and communal, and above all social cohesion, again on both personal and communal levels. We then proceed to how instruments began, with a brief survey of the surviving examples from the Mousterian period onward, including the possible Neanderthal evidence and the extent to which they showed “artistic” potential in other fields. We warn that our performance on replicas of surviving instruments may bear little or no resemblance to that of the original players. We continue with how later instruments, strings, and skin-drums began and developed into instruments we know in worldwide cultures today. The sound of music is then discussed, scales and intervals, and the lack of any consistency of consonant tonality around the world. This is followed by iconographic evidence of the instruments of later antiquity into the European Middle Ages, and finally, the history of public performance, again from the possibilities of early humanity into more modern times. This paper draws the ethnomusicological perspective on the entire development of music, instruments, and performance, from the times of H. neanderthalensis and H. sapiens into those of modern musical history, and it is written with the deliberate intention of informing readers who are without special education in music, and providing necessary information for inquiries into the origin of music by cognitive scientists.

How Did Music Begin? Was it via Vocalization or was it through Motor Impulse?

But even those elementary questions are a step too far, because first we have to ask “What is music?” and this is a question that is almost impossible to answer. Your idea of music may be very different from mine, and our next-door neighbor’s will almost certainly be different again. Each of us can only answer for ourselves.

Mine is that it is “Sound that conveys emotion.”

We can probably most of us agree that it is sound; yes, silence is a part of that sound, but can there be any music without sound of some sort? For me, that sound has to do something—it cannot just be random noises meaning nothing. There must be some purpose to it, so I use the phrase “that conveys emotion.” What that emotion may be is largely irrelevant to the definition; there is an infinite range of possibilities. An obvious one is pleasure. But equally another could be fear or revulsion.

How do we distinguish that sound from speech, for speech can also convey emotion? It would seem that musical sound must have some sort of controlled variation of pitch, controlled because speech can also vary in pitch, especially when under overt emotion. So music should also have some element of rhythm, at least of pattern. But so has the recital of a sonnet, and this is why I said above that the question of “What is music?” is impossible to answer. Perhaps the answer is that each of us in our own way can say “Yes, this is music,” and “No, that is speech.”

Must the sound be organized? I have thought that it must be, and yet an unorganized series of sounds can create a sense of fear or of warning. Here, again, I must insert a personal explanation: I am what is called an ethno-organologist; my work is the study of musical instruments (organology) and worldwide (hence the ethno-, as in ethnomusicology, the study of music worldwide). So to take just one example of an instrument, the ratchet or rattle, a blade, usually of wood, striking against the teeth of a cogwheel as the blade rotates round the handle that holds the cogwheel. This instrument is used by crowds at sporting matches of all sorts; it is used by farmers to scare the birds from the crops; it was and still is used by the Roman Catholic church in Holy Week when the bells “go to Rome to be blessed” (they do not of course actually go but they are silenced for that week); it was scored by Beethoven to represent musketry in his so-called Battle Symphony, a work more formally called Wellingtons Sieg oder die Schlacht bei Vittoria , Op.91, that was written originally for Maelzel’s giant musical box, the Panharmonicon. Beethoven also scored it out for live performance by orchestras and it is now often heard in our concert halls “with cannon and mortar effects” to attract people to popular concerts. And it was also, during the Second World War, used in Britain by Air-Raid Precaution wardens to warn of a gas attack, thus producing an emotion of fear. If it was scored by Beethoven, it must be regarded as a musical instrument, and there are many other noise-makers that, like it, which must be regarded as musical instruments.

And so, to return to our definition of music, organization may be regarded as desirable for musical sound, but that it cannot be deemed essential, and thus my definition remains “Sound that conveys emotion.”

So Now We Can Ask Again, “How Did Music Begin?”

But then another question arises: is music only ours? We can, I think, now agree that two elements of music are melody, i.e., variation of pitch, plus rhythmic impulse. But almost all animals can produce sounds that vary in pitch, and every animal has a heart beat. Can we regard bird song as music? It certainly conveys musical pleasure for us, it is copied musically (Beethoven again, in his Pastoral Symphony , no.6, op. 68, and in many works by other composers), and it conveys distinct signals for that bird and for other birds and, as a warning, for other animals also. Animal cries also convey signals, and both birds and animals have been observed moving apparently rhythmically. But here, we, as musicologists and ethnomusicologists alike, are generally agreed to ignore bird song, animal cries, and rhythmic movement as music even if, later, we may regard it as important when we are discussing origins below. We ignore these sounds, partly because they seem only to be signals, for example alarms etc, or “this is my territory,” and partly, although they are frequently parts of a mating display, this does not seem to impinge on society as a whole, a feature that, as we shall see, can be of prime importance in human music. Perhaps, too, we should admit to a prejudice: that we are human and animals are not…

So now, we can turn to the questions of vocalization versus motor impulse: which came first, singing or percussive rhythms? At least we can have no doubt whatsoever that for melody, singing must long have preceded instrumental performance, but did physical movement have the accompaniment of hand- or body-clapping and perhaps its amplification with clappers of sticks or stones, and which of them came first?

Here, we turn first to the study of the potentials of the human body. There is a large literature on this, but it has recently been summarized by Iain Morley in his The Prehistory of Music ( Morley, 2013 ). So far as vocalization is concerned, at what point in our evolution was the vocal tract able to control the production of a range of musical pitch? For although my initial definition of music did not include the question of pitch, nor of rhythm, once we begin to discuss and amplify our ideas of music, one or other of these, does seem to be an essential—a single sound with no variation of pitch nor with any variation in time can hardly be described as musical.

Studies based on fossil remains of the cranium and jaw formation of the early species of homo suggest that while Homo ergaster from between two million and a million and a half years ago could produce some variation of pitch but perhaps without much breath control, Homo erectus may have had greater ability, and Homo heidelbergensis , and certainly its later development from around a million years ago into the common ancestor of Homo neanderthalensis and Homo sapiens , could certainly “sing” as well as we can, though of course we can have no evidence of whether they could control such ability, whether they used it, and if so to what extent. So we can say that vocalization, while absent from the capability of our cousins the great apes and of the early forms of Homo , could be as old as at least a million years. It would seem that Homo heidelbergensis had the muscular abilities, but perhaps not the full mental capacities and that it was not until H. sapiens arrived that all the requirements for vocalization were in place, both exported and imported, and possibly not even in the earliest stages of the evolution of H. sapiens . It is here that there is controversy over the relative musical abilities of H. neanderthalensis and H. sapiens , to which in due course we shall return.

Much of this work also discusses the origins of speech as well as that of music. The two processes seem to have much the same physiological requirements, the ability to produce the various consonants and vowels that enable speech, and the ability to control discrete musical pitches. But this capacity goes far beyond the ability to produce sounds.

All animals have the ability to produce sounds, and most of these sounds have meanings, at least to their ears. Surely, this is true also of the earliest hominims. If a mother emits sounds to soothe a baby, and if such sound inflects somewhat in pitch, however vaguely, is this song? An ethnomusicologist, those who study the music of exotic peoples, would probably say “yes,” while trying to analyze and record the pitches concerned. A biologist would also regard mother–infant vocalizations as prototypical of music ( Fitch, 2006 ). There are peoples (or have been before the ever-contaminating influence of the electronic profusion of musical reproduction) whose music has consisted only of two or three pitches, and those pitches not always consistent, and these have always been accepted as music by ethnomusicologists. So we have to admit that vocal music of some sort may have existed from the earliest traces of humanity, long before the proper anatomical and physiological developments enabled the use of both speech and what we might call “music proper,” with control and appreciation of pitch.

In this context, it is clear also that “music” in this earliest form must surely have preceded speech. The ability to produce something melodic, a murmuration of sound, something between humming and crooning to a baby, must have long preceded the ability to form the consonants and vowels that are the essential constituents of speech. A meaning, yes: “Mama looks after you, darling,” “Oy, look out!” and other non-verbal signals convey meaning, but they are not speech.

The possibilities of motor impulse are also complex. Here, again, we need to look at the animal kingdom. Both animals and birds have been observed making movements that, if they were humans, would certainly be described as dance, especially for courtship, but also, with the higher apes in groups. Accompaniment for the latter can include foot-slapping, making more sound than is necessary just for locomotion, and also body-slapping ( Williams, 1967 ). Can we regard such sounds as music? If they were humans, yes without doubt. So how far back in the evolutionary tree can we suggest that motor impulse and its sonorous accompaniment might go? I have already postulated in my Origins and Development of Musical Instruments ( Montagu, 2007 , p. 1) that this could go back as far as the earliest flint tools, that striking two stones together as a rhythmic accompaniment to movement might have produced the first flakes that were used as tools, or alternatively that interaction between two or more flint-knappers may have led to rhythms and counter-rhythms, such as we still hear between smiths and mortar-and-pestle millers of grains and coffee beans. This, of course, was kite-flying rather than a wholly serious suggestion, but the possibilities remain. At what stage did a hominim realize that it could make more sound, or could alleviate painful palms, by striking two sticks or stones together, rather than by simple clapping? Again we turn to Morley and to the capability of the physiological and neurological expression of rhythm.

The physiological must be presumed from the above animal observations. The neurological would again, at its simplest, seem to be pre-human. There is plenty of evidence for gorillas drumming their chests and for chimpanzees to move rhythmically in groups. However, apes’ capacity for keeping steady rhythm is very limited ( Geissmann, 2000 ), suggesting that it constitutes a later evolutionary development in hominins. Perceptions of more detailed appreciation of rhythm, particularly of rhythmic variation, can only be hypothesized by studies of modern humans, especially of course of infantile behavior and perception.

From all this, it would seem that motor impulse, leading to rhythmic music and to dance could be at least as early as the simplest vocal inflection of sounds. Indeed, it could be earlier. We said above that animals have hearts, and certainly, all anthropoids have a heartbeat slow enough, and perceptible enough, to form some basis for rhythmic movement at a reasonable speed. Could this have been a basis for rhythmic movement such as we have just mentioned? This can only be a hypothesis, for there is no way to check it, but it does seem to me that almost all creatures seem to have an innate tendency to move together in the same rhythm when moving in groups, and this without any audible signal, so that some form of rhythmic movement may have preceded vocalization.

But Why Does Music Develop from Such Beginnings? What is the Purpose of Music?

There are four obvious purposes: dance, personal or communal entertainment, communication, and ritual.

Dance we have already mentioned, though we can never know whether rhythmic motion led to the use of accompaniment, or whether the use of rhythm for any work led to people moving rhythmically in a way that became dance. It is well accepted in anthropology that when people are working, or moving together, their movements fall into a rhythm, that people may grunt and make other noises into that rhythm. The grunts may move into something that verges on or morphs into song; the other noises may be claps or beating pairs of objects together (concussive) or beating one object on another (percussive). Such objects can only be idiophonic, such as sticks, stones, and other solid objects that require no additional features to help them make a sound, in the classificatory system for instruments ( Hornbostel and Sachs, 1914 ). This is simply because to create a drum with a skin (membranophones) is a complex process, because a skin will not produce sound unless it is under tension.

There is no doubt whatsoever that rhythmic sound without any melodic input must be regarded as music. It appears in many cultures, even if rarely, and we have Varèse’s Ionization to take as an example from our modern orchestral repertoire.

Our second purpose was personal or communal entertainment. Communal entertainment, to some extent, overlaps with dance and with rhythmic work; personal entertainment overlaps for the mother and baby, mentioned above, with communication, as does the traveler using an instrument to indicate to people or villages that he passes that his purpose is peaceful and that he is not a robber intent on purloining their property, a well-known practice anthropologically but one that we can have no way to measure its antiquity.

Our third purpose, communication by musical means is again widespread. We have the “bush telegraph” in Africa and other parts of the world with slit drums and other instruments, the alphorn in Switzerland and in other mountainous or marshy regions, the conch in Papua New Guinea, as random examples of the use of an instrument to pass messages. We have the whistling language of the Canary Islands ( silbo ) and many other parts of the world, and the high vocal calls of other peoples as examples of non-instrumental music for the same purpose.

Our fourth purpose, ritual, is a well-known trap in archeology and anthropology. Any object, any practice that cannot otherwise be explained, is assigned as “ritual.” But there seems to be no form of religion, to use that word in its widest sense, that does not attract music to its practices. And here, we have another conflict, again that between music and speech. Schönberg’s “invention” of Sprechgesang , an interface between speech and music, was nothing new. Many forms of ritual chants would be difficult to notate precisely in pitch; the words are spoken but they are inflected up and down quasi-melodically. Some bardic narrative is also an example of this, while often breaking intermittently into song. In both cases, the musical inflection renders the text less boring and helps the speaker with his or her memory of the text. It is undoubtedly speech, for the meaning of the words is the essential part, but there is also the element of pitch variation that would make an ethnomusicologist claim it to be music even while the practitioner would often vehemently deny any such claim, especially within the stricter forms of Islam, those in which music is forbidden.

Seemingly more important than these fairly obvious reasons for why music developed is one for why music began in the first place. This is something that Steven Mithen mentions again and again in his book, The Singing Neanderthals ( Mithen, 2005 ): that music is not only cohesive on society but almost adhesive. Music leads to bonding, bonding between mother and child, bonding between groups who are working together or who are together for any other purpose. Work songs are a cohesive element in most pre-industrial societies, for they mean that everyone of the group moves together and thus increases the force of their work. Even today “Music while you Work” has a strong element of keeping workers happy when doing repetitive and otherwise boring work. Dancing or singing together before a hunt or warfare binds the participants into a cohesive group, and we all know how walking or marching in step helps to keep one going. It is even suggested that it was music, in causing such bonding, that created not only the family but society itself, bringing individuals together who might otherwise have led solitary lives, scattered at random over the landscape.

Thus, it may be that the whole purpose of music was cohesion, cohesion between parent and child, cohesion between father and mother, cohesion between one family and the next, and thus the creation of the whole organization of society.

Much of this above can only be theoretical—we know of much of its existence in our own time but we have no way of estimating its antiquity other than by the often-derided “evidence” of the anthropological records of isolated, pre-literate peoples. So let us now turn to the hard evidence of early musical practice, that of the surviving musical instruments. 1

This can only be comparatively late in time, for it would seem to be obvious that sound makers of soft vegetal origin should have preceded those of harder materials that are more difficult to work, whereas it is only the hard materials that can survive through the millennia. Surely natural materials such as grasses, reeds, and wood preceded bone? That this is so is strongly supported by the advanced state of many early bone pipes—the makers clearly knew exactly what they were doing in making musical instruments, with years or generations of experiment behind them on the softer materials. For example, some end-blown and notch-blown flutes, the earliest undoubted ones that we have, from Geissenklösterle and Hohle Fels in Swabia, Germany, made from swan, vulture wing (radius) bones, and ivory in the earliest Aurignacian period (between 43,000 and 39,000 years BP), have their fingerholes recessed by thinning an area around the hole to ensure an airtight seal when the finger closes them. This can only be the result of long experience of flute making.

So how did musical instruments begin? First a warning: with archeological material, we have what has been found; we do not have what has not been found. A site can be found and excavated, but if another site has not been found, then it will not have been excavated. Thus, absence of material does not mean that it did not exist, only that it has not been found yet. Geography is relevant too. Archeology has been a much older science in Europe than elsewhere, so that most of our evidence is European, whereas in Africa, where all species of Homo seem to have originated, site archeology is in its infancy. Also, we have much evidence of bone pipes simply because a piece of bone with a number of holes along its length is fairly obviously a probable musical instrument, whereas how can we tell whether some bone tubes without fingerholes might have been held together as panpipes? Or whether a number of pieces of bone found together might or might not have been struck together as idiophones? We shall find one complex of these later on here which certainly were instruments. And what about bullroarers, those blades of bone, with a hole or a constriction at one end for a cord, which were whirled around the player’s head to create a noise-like thunder or the bellowing of a bull, or if small and whirled faster sounded like the scream of a devil? We have many such bones, but how many were bullroarers, how many were used for some other purpose?

So how did pipes begin? Did someone hear the wind whistle over the top of a broken reed and then try to emulate that sound with his own breath? Did he or his successors eventually realize that a shorter piece of reed produced a higher pitch and a longer segment a lower one? Did he ever combine these into a group of tubes, either disjunctly, each played by a separate player, as among the Venda of South Africa and in Lithuania, or conjointly lashed together to form a panpipe for a single player? Did, over the generations, someone find that these grouped pipes could be replaced with a single tube by boring holes in it, with each hole representing the length of one of that group? All this is speculation, of course, but something like it must have happened.

Or were instruments first made to imitate cries? The idea of the hunting lure, the device to imitate an animal’s cry and so lure it within reach, is of unknown age. Or were they first made to imitate the animal in a ritual to call for the success of tomorrow’s hunt? Some cries can be imitated by the mouth; others need a tool, a short piece of cane, bits of reed or grass or bone blown across the end like a key or a pen-top. Others are made from a piece of bark held between the tongue and the lip (I have heard a credit card used in this way!). The piece of cane or bone would only produce a single sound, but the bark, or in Romania a carp scale, can produce the most beautiful music as well as being used as a hunting call. The softer materials will not have survived and with the many small segments of bone that we have, there is no way to tell whether they might have been used in this way or whether they are merely the detritus from the dining table.

We have many whistles made from an animal phalange or toe bone, blown between a pair of protrusions at one end, across a sound hole near the center. Two of them come from the Mousterian period of the Middle Paleolithic, over 50,000 years ago, and there are many from the Aurignacian down to the Magdalenian and later; most, but not all, are reindeer phalanges. D’Errico has warned us, though, that the “sound hole” on many of these look as though they were made from a carnivore bite ( D’Errico et al., 2003 ). It was in the Mousterian period that the Neanderthals co-existed with Homo Sapiens ; the latter arrived in Europe between fifty and forty thousand years ago (though far earlier in the Near East), whereas Neanderthals had long been established in Europe, perhaps as long as 200,000 years before. Whether any that were blown by humans were used for signaling, or whether they were also used for music we cannot know, but whistles are certainly regarded as musical instruments.

More controversially in this Mousterian period, and certainly associated with other Neanderthal remains, is the young cave bear femur from the Divje Babe cave in Slovenia, dated to around 60,000 years Before the Present (BP). This has two holes in it and what might be three others at the broken-off ends, two on one side and one on the other. The fragment of bone is just over 10 cm long and while many people have claimed it as a flute, for it can certainly produce several pitches when reproductions of it are blown, many others have claimed that the holes are the result of other carnivores gnawing it, especially at the ends. As for the two complete holes, some writers have claimed that they are just the right size, shape, and spacing to have been produced by bears, for whose presence in the cave there is ample evidence, nor does there seem to be any trace of any possible human work on the bone. There is a very considerable literature on this possible instrument, well summed up and cited by Morley and by D’Errico et al., and the general consensus had been that it was not a musical instrument but simply the result of animal action. Nevertheless, the original discoverers have returned to the attack with a recent publication ( Turk, 2014 ) which goes to show that human agency not only could have but did pierce those holes. For now, we can only leave this question open, with all the problems of an unicum; there are convincing conclusions on both sides of the argument, with at present rather greater weight on the “yes” side, partly due to this recent publication, and partly to the evidence in the following paragraph. What we really need are more examples from the Mousterian period.

This bone does raise the whole question of whether H. neanderthalensis knew of or practised music in any form. For rhythm, we can only say surely, as above—if earlier hominids could have, so could H. neanderthalensis . Could they have sung? A critical anatomical feature is the position of the larynx ( Morley, 2013 , 135ff); the lower the larynx in the throat the longer the vocal cords and thus the greater flexibility of pitch variation and of vowel sounds (to put it at its simplest). It would seem to have been that with H. heidelbergensis and its successors that the larynx was lower and thus that singing, as distinct from humming, could have been possible, but “seems to have been” is necessary because, as is so often, this is still the subject of controversy. However, it does seem fairly clear that H. neanderthalensis could indeed have sung. It follows, too, that while the Divje Babe “pipe” may or may not have been an instrument, others may yet be found that were instruments. There is evidence that the Neanderthals had at least artistic sensibilities, for there are bones with scratch marks on them that may have been some form of art, and certainly there is a number of small pierced objects, pieces of shell, animal teeth, and so forth, found in various excavations that can only have served as beads for a necklace or other ornamentation – or just possibly as rattles. There have also been found pieces of pigments of various colors, some of them showing wear marks and thus that they had been used to color something, and at least one that had been shaped into the form of a crayon, indicating that some reasonably delicate pigmentation had been desired. Burials have been found, with some small deposits of grave goods, though whether these reveal sensibilities or forms of ritual or belief, we cannot know ( D’Errico et al., 2003 , 19ff). There have also been found many bone awls, including some very delicate ones which, we may presume, had been used to pierce skins so that they could be sewn together. All this leads us to the conclusion that the Neanderthals had at least some artistic and other feelings, were capable of some musical practices, even if only vocal, and were clothed, rather than being the grunting, naked savages that have been assumed in the past.

It is in the Middle and Upper Paleolithic, from the Aurignacian period, which starts around 43,000 BP in eastern Europe and around 40,000 in the west, to the Magdalenian and later, ending around 10,000 BP, which we have a very considerable number of instruments, plus a few representations. Many of them, like those from Geissenklösterle above, are end-blown flutes made of bone, most commonly of large birds such as vultures and swans. Some of them are blown via a notch; some appear to be duct flutes, similar to our recorders, though of course the block made of wood, pith, or fiber has not survived—more probably, they are likely to have been tongue-duct flutes, using the tongue in the end instead of a block, and some are listed as such in Morley’s tables—and others may have been plain-end blown, diagonally across the top, like the Arab nay . With these last, though, it is possible that a reed was used as the sound generator, either a double reed like that of our oboe or a split-cane single reed like that of many Arab instruments, or possibly even lip-blown (trumpeted), though the narrowness of the bore makes this seem less likely. It is, therefore, probably better to refer to this last group as pipes, rather than as flutes.

Reproductions of many can be and have been played, but there is little to be learnt from this practice. We know what pitches and sounds we can get out of them, but unless we know their playing techniques, which of course we do not know, we cannot tell what sort of pitches and tone qualities they would have obtained in antiquity. Every recorder and tin-whistle player knows of a number of ways to inflect the pitch and the tone; every Arab nay player knows even more, and ethnomusicologists have produced evidence for even more, and our experimental musicians have shown that quite extraordinary pitches and sounds can be obtained from many of our orchestral instruments, sounds that their makers or normal players never conceived. Thus the archeologists (who are seldom trained musicians), who publish the scales and pitches of the pipes that they have found, can give us no more than conjecture and the experience of their own musicality. I have a collection of musical instruments from all over the world; I know the sounds that I can get out of them, but without the presence of the original player, or a field recording of the original player on that very instrument, I have no way to tell what sounds or pitches he or she produced. So much less can we have any idea what sounds and pitches were heard in the Paleolithic times.

However, there is one salient point, emphasized by D’Errico: a significant number of these pipes has varied spacing of finger holes. While, it would seem that the majority have the finger holes evenly spaced along the tube, there are certainly some that have a wider gap between the second and third holes. There are two fairly obvious possible reasons for this: one is that their “scale” of pitches had intervals similar to wholetones and minor thirds; the other that it was convenient or comfortable to have a wider gap between the two hands. This latter suggestion is raised because it was a standard feature of our flutes from the later Middle Ages right through into the early nineteenth century, and this was not only because from around 1700 the middle joint of the Baroque flute was divided into an upper and lower joint at this point – the earlier one-piece flutes also showed this gap. There are also some Aurignacian flutes or pipes that have one hole closer to another, showing that a semitone or a small wholetone was desired. Thus, these details emphasize that not only were these well-developed instruments, with the bodies well-scraped and smoothed, the finger holes with secure seating for the fingers, a certain amount of incised decoration, but that also there was a desire for precise tuning, and that they were not just made to produce fairly random pitches.

In addition, there is the point that many of these features appear both in Geissenklösterle in Germany, in Isturitz in France, in Spain, and also elsewhere, and over long periods of time, strongly suggesting that populations were not isolated but that there were links between them. This is not so surprising. If H. sapiens had traveled across Africa and into Europe, surely they could also travel between these areas and elsewhere.

There is little point in listing all these pipes; all the Paleolithic examples from Europe, or close by, found before 2013 are listed by Morley in his Appendices.

Were there other instruments? There is at least one conch trumpet, found in the Marsoulas cave, in the Haute-Garonne area of southern France, dating from around 20,000 years BP. Shell is a hard material that survives the ages, and although we have so far only this one example from the Upper Paleolithic, we have a very considerable number from the Neolithic times, some of them much further from the sea, so it is fair to assume a continuous use (Montagu, in press). 2 So what about animal horns? Here the material is soft, and only in very dry conditions such as desert sands do any survive; none of those that I have heard of or seen were blowing horns, but it seems likely that they existed. For blowing, the horn must be naturally hollow, such as those of the cow family, sheep and goats, antelopes, elephant tusks, hollow wood, gourds, and wide-bore bamboo, with the tip broken or cut off, or a hole bored in the side; such were surely blown in high antiquity ( Montagu, 2014 ). There are several bullroarers from the Magdalenian period that we can be certain were instruments. There are many phalange whistles later than the Mousterian ones noted above. There are rasps, usually bones notched along their length, which would have been scraped with another bone or a stone for rhythmic music.

There is the complex of mammoth bones dating from around 20,000 BP, found in the Ukraine and published by Bibikov (1981) . Many of the bones show signs of wear, almost certainly from repeated striking, and others, though this is not mentioned in the English summary, have striations similar to those of rasps, suggesting that some were scraped whereas others were struck. It is claimed that this was an ensemble, and although it would be difficult to prove that this was so, it would be even more difficult to show that each of these bones was struck only singly as an individual solo instrument. So here perhaps we have the first evidence of an “orchestra.”

There are from the Magdalenian period, some 12,000 years BP, the caves themselves, where not only were stalactites struck but the caves themselves were used as resonators for sounds; both Lucie Rault and Lya Dams have brought together a number of convincing reports of this ( Dams, 1985 ; Rault, 2000 ). Resonant stones must also have been struck outside the caves, the so-called rock gongs, boulders struck on resonant points, and these are of unknown antiquity but many bear well-worn cup marks on their surfaces. Rock gongs were first reported by Bernard Fagg in Nigeria, and following his article ( Fagg, 1956 ), many more have been reported from around the world ( Fagg, 1997 ).

There is no evidence in the Paleolithic period for stringed instruments nor for skin drums.

At what point in history did someone discover that by cupping the hands together and blowing between the knuckles of the thumbs produced a sound? This is a vessel flute or ocarina whose pitch is varied by moving the fingers to alter the area of open hole. Many peoples have long used gourds and other hollow vegetal objects, and today pottery, to play music in this way, also with the hands as hunting lures, but since there are no animal bones of such a shape, we can have no evidence of vessel flutes earlier than the Neolithic, in which period pottery first came into use.

Did voice changers precede instruments? Did someone sing into a hollow object to change his voice from that of a human into that of a spirit or a deity? Was a shell sung into before ever a shell was blown? This precedence is something that has at times been suggested, but it can never be more than a hypothesis for we have no evidence to prove it. We do know that certain Greek statues had voice changers built in, usually a tube with a skin over one end, our kazoo, and there are many African masks with such a device.

Stringed instruments probably originated by the Mesolithic period, and certainly by the Neolithic, for it is in those periods that we begin to find flint arrow-heads, and the archer’s bow and the musical bow are symbiotic as we shall see below ( Balfour, 1899 ).

Skin drums (membranophones), as we said above, need the skin to be under tension to function. At what stage could there have been frames to which a skin could have been fastened securely enough to be tight enough to play? One can only say as early as skins were dressed, wetted, and dried on a frame, but since neither skins nor wooden frames, nor hollow logs, can ever have survived, this is simply an unknown; ceramic bodies rigid enough to support the skins can only have been available in or shortly before the Neolithic period.

So far, we have been discussing instruments only from Europe or its immediate environment. Simply, this is because where the evidence is. Archeology has been going on longer in Europe than elsewhere, as we have said. Much is being found now in China, but since most of it has been published in Chinese, much of this information is inaccessible, at least to me.

All the instruments that we have discussed above continued through the Neolithic and, with archery and pottery available, many others have joined them.

The earliest stringed instrument is undoubtedly the musical bow ( Balfour, 1899 ). The one string instrument that might possibly be earlier is one that is identical with an animal trap—a noosed cord, presumably gut or sinew, running from a bent stick or branch to a peg in the ground. When an animal puts its head or leg into the noose, the cord is jerked from the peg and the stick or branch springs up and traps the animal. It has been suggested by Sachs, Balfour, and others that the hunter may also have plucked the string, so creating the ground bow, varying the tension of the cord, and thus the pitch, by bending the stick or branch. The ground harp is of unknown antiquity—our only evidence for the existence of the instrument is nineteenth-century reports from anthropologists.

Bows themselves, of course, never survive, but the presence of arrowheads in the lithic evidence proves their existence. Whether the archer’s bow preceded the musician’s or vice versa is arguable, but man’s addiction to warfare, and even more to hunting, makes the archer’s the more likely. We have ethnographic evidence for the use of the same bow for both purposes by the same person, but each developed in different ways, the archer’s for strength and the musician’s for producing musical sounds in different ways. The string of the musical bow is most commonly tapped by a light stick, initially presumably by an arrow, and is held to the player’s mouth where, by changing the shape of the mouth, different overtones are sounded as with the jews harp (better and less prejudiciously called trump, which is the earlier English name). By dividing the string with a loop of cord linking the string to the stave, or by shortening the string at one end by the thumb of the holding hand, two fundamentals, each with their own overtones, makes a much greater range of pitches available. Attaching a gourd resonator to the stave creates greater volume, and opening or closing the mouth of the gourd against the player’s chest will again elicit overtones. Both these forms survive to the present day in various modifications and many parts of the world, especially in Africa south of the Sahara ( Kirby, 1934 ). A third form consists of attaching several bows to one resonator to form a pluriarc, as is still found in Central Africa.

One can postulate developments from both the gourd bow and the pluriarc. The gourd, eventually of wood, can be built on to one end of the stave to create both the category of instruments called lutes, with a straight stave as the neck, and of harps, with a curved stave. If the two outermost bows of the pluriarc become rigid, with a cross bar running between them to hold the distal ends of the strings of the inner bows, which then become redundant, the instrument is then much more stable and is called a lyre. Whether such developments took place, or whether lutes, harps, and lyres were independently invented, we can never know, but my own guess, based partly on various intermediate forms in various cultures, is for this process of development.

As for drums, frame drums are still ubiquitous around the world today, not only with our own tambourine, but a wooden or pottery body of manifold shapes exists almost everywhere. One possible early source for another type of drum is created by fixing the skin of the animal just eaten, over the top of the pot in which it had been cooked, so creating the instrument very appropriately called the kettledrum, using the word kettle in the sense of a caldron.

Another very common use of pottery is to create a rattle, a vessel containing seeds, pebbles, or nodules of pottery. Such vessel rattles must have been long preceded by gourds or woven leaves or baskets, all of which are still common today.

Once humanity entered the metal ages, the potentialities of instruments becomes infinite.

We can never know to what extent any groups of instruments or voices played together in high antiquity, though the existence of the group of mammoth bones above, does strongly suggest an ensemble. Not until the days of representational iconography, as in Mesopotamia and Egypt, or with the introduction of literacy, such as our Bible, do we have any real evidence. We have plenty of information from these sources.

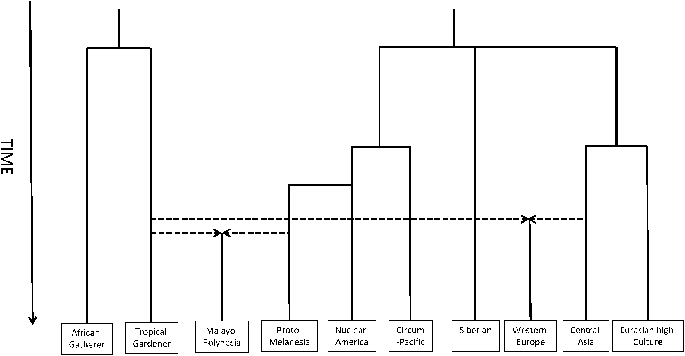

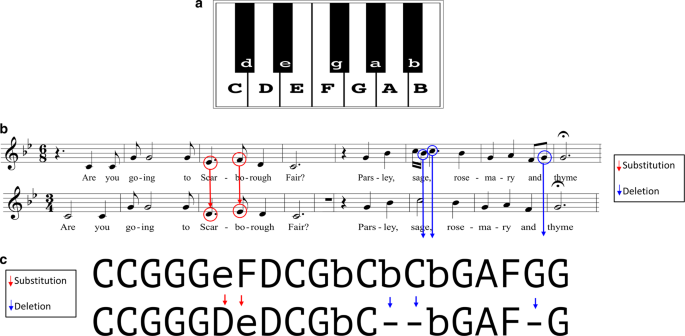

What then did music sound like? We have early notations from Sumeria ( Galpin, 1936 ) and Ancient Greece, the well-known hymn to Apollo, covering a wide range of pitches; Hickmann tried to derive a notation from hand-signals, called cheironomy, portrayed in Egyptian paintings and carvings ( Hickmann, 1961 ). It has been thought by ethnomusicologists that less-advanced cultures than those, used pentatonic scales (five steps to the octave) such as we can still hear today in some areas, and perhaps even fewer steps with or without knowledge of the octave. But for these, naturally there is no evidence. Even with Sumerian, Greek, and Egyptian systems, the various transcriptions of which are all controversial, we cannot know the actual sounds, for not until the later classical Greek period do we have written evidence of the sizes of scalar steps.

We do know, from the transcription of cuneiform tablets, that it was the Babylonians, and very possibly the Sumerians before them, who cataloged the skies and their constellations, establishing thus the basics of the calendar and of time that we use today, and who invented the hexadecimal system of mathematics. They turned their attention to sound also, and the Sumerians developed a system of diatonic scales based on alternating fourths and fifths. The Greeks, who took such knowledge from them, devised a diatonic scale based on the ratios of the harmonic series, starting from the eighth partial, a scale today called Just Temperament, one that is still used today by unaccompanied voices and sometimes by bowed string players or wind instruments playing without keyboards. For other instruments, such as lyres and harps, Just Temperament could also serve well, but only and until the players wished to change key; as soon as they did so, for reasons more complex than are needed here but are discussed below, chaos would ensue. Nevertheless, despite the purity of such a scale, we know that even the Greeks used other and more complex scales ( Barbour, 1951 ) as, from the anthropological record, did many other peoples. Therefore, despite such transcriptions as we have of the ancient texts above, we can have no certain knowledge of what the music sounded like, for we do not know the exact sizes of the steps of the scales.

Even within Europe the 13th partial, the so-called alphorn fa, halfway between F and F-sharp appears in vocal music and on bagpipes as well as on natural horns and trumpets; the neutral third, between E and E-flat also appears, and as we shall see, the third is the most mutable interval in our classical music. In the Balkans, people sing in close seconds rather than wider intervals or unisons.

One thing that the ethnomusicologists can tell us is that either humanity has no inbuilt sense of consonant tonality, or that other people’s sense of consonance is different from ours. The musical bow will by its nature produce the pitches of Just Temperament, for all its pitches are the overtones of the harmonic series, but despite this some peoples, who use the bow, will sing in seven equal steps to the octave. The one interval that does seem to be common to almost all peoples is the octave; this most probably originates with men and women singing in “unison” together, for women’s voices tend to be an octave higher than men’s. It is also a natural step to recognize when any piece of music extends beyond the range of one octave, and this repetition of scalar steps beyond the octave is built into many woodwind fingering systems.

We have many other examples of other scales that do not use what we, in our culture, may consider to be pure tuning. Let us take just one example that may be familiar to many of us today, the Javanese gamelan. This uses two different scales, slendro and pelog . Both employ the octave, but neither uses a pure fifth or third, the notes that make up our “common chord.” Slendro has five almost equal steps to the octave; pelog has seven rather less equal steps. Not one of the steps of slendro is the same as those of pelog . Nor were the slendro or pelog in Java exactly the same between one gamelan and another, though similar, before the recent days when almost all gamelans are tuned to the pitches used by Radio Yogyakarta.

Nor are the scales of the Near and Middle East compatible with ours ( Wizārat al-Tarbiyah wa-al-Ta‘līm, 1934 ). Nor even, save for the octave, are the pitches of Just Intonation the same as those of the Equal Temperament that we use on our pianos today. Each culture develops the tuning system that best suits its ideas of musicality. It is up to the cognitive scientists to determine why this should be so, but they have to admit, if they are willing to listen to the exotic musics of the world, that these differences exist.

Let us now return to the history of music and of the instruments on which it was played.

At least we do know what instruments some peoples used in the later millennia BCE, for not only do we have a few survivals in our museums from the Sumerian, Babylonian, Egyptian, Greek, Etruscan, and Roman periods, and also from the Orient, but we also have a wealth of iconography, much of it published in the Musikgeschichte in Bildern series by the Deutsche Verlag für Musik in Leipzig from the 1960s onward. This series is, alas, incomplete, for its publication ceased with the reunification of Germany.

We see among the Sumerians and Babylonians lyres and harps of various kinds, the latter quite small, a horizontal or vertical sound box with, at the distal end, a forepillar standing up at 90°, whereas in Egypt harps were normally curved, some of them as tall as the player, others, called the bow harp, were small enough to be held on the shoulder, and these last gradually passed into Central Africa where they are still found today. We see also lutes, a hollowed sound box like a small trough, with the open top covered with a skin to form the belly. A rod acts as the neck and passes through slits in the skin to hold it in place. These also still appear in Africa today. All these instruments were plucked, either with the fingers or a plectrum—the bow, such as we use on our fiddles, was as yet far in the future. There were pipes, usually double, held one in each hand, though sometimes, especially later in Egypt, lashed together so that the fingers of each hand could reach across both pipes. There were occasional drums, some very large, and many forms of rattles. We also see many of these instruments combined into what appear to be ensembles. This use of bands of instruments is confirmed in literature, for example in chapter 3 of the book of Daniel in our Bible where, when all the instruments play together, all those present bow down to the deity. Again in the Bible (II Samuel 6), a band of instruments escorts the Ark of the Covenant to David’s city, with David dancing before them to the scorn of his queen. 3 Beware, however, of the huge choirs and groups of instruments in the two books of Chronicles; this is a late account, written long after any of the events it records, and smacks strongly of a child’s playground exaggeration: “my brother is bigger and better than yours.”

In ancient Greece, the lyre and the double pipe, the aulos , predominated. Lyres came in three forms. The simplest, the chelys or lyra , had a tortoise-shell body with two vertical curved wooden rods or horns, set in the shell with a third rod running horizontally as the cross bar. The strings were attached at one end to the bottom of the shell and at the other were twisted with kollopes , strips of skin, and wound round the horizontal bar. These kollopes set firmly enough on the bar to hold a tuning, but could be turned on the bar to retune. This type of lyre was taught to, and used for after-dinner symposia, by all educated people. It traveled up the Nile to the Meroitic people, probably in the Hellenistic period, and eventually throughout East Africa, where it is still used today, with the skin kollopes replaced with strips of cloth and the tortoise-shell with a gourd or wooden body as the resonator, and a skin belly. A more elegant form of Greek lyre, with longer curved arms, was called the barbiton . The professional musician’s version, the kithara , was much more elaborate, with a wooden box-body and with what appears to be some form of semi-mechanized tuning devices. All three had gut strings that were normally plucked with a plectrum of wood, bone, or ivory, and all three are seen on many Greek vases and statues.

The aulos was a reed-pipe, shorter and somewhat stouter than the Sumerian and Egyptian; whether with a double reed like that of the oboe or a single reed like that of early folk clarinets as in the Near East today, is much argued, but Schlesinger’s illustrations clearly show both types, though probably more often with the double reed ( Schlesinger, 1939 ). The aulos passed on to Rome, where it was known as the tibia , to which quite elaborate tuning mechanisms were applied, with rings that could be turned to close off one hole and open another slightly differently placed, so as to play in a different key or mode. There was also a single pipe, the monaulos , and that is still found today, with a large double reed, all down the Silk Road, from Turkey, Kurdistan, and Armenia to China, Korea, and Japan. Whether it traveled east from Greece, or whether it originated in Central Asia like a number of other instruments and then traveled both east and west, is debatable.

That several instruments originated in Central Asia, probably somewhere between Persia and the Caspian Sea, is undoubted. The gong started there and was known in the Near East by St Paul (I Corinthians 13:1) as chalkos ēchon ( Montagu, 2001 , 123). The Chinese encyclopedias said that they got the gong from the West, which also suggests a Central Asian origin. The long trumpet seems to have started there also and it spread across the whole of Asia and to Greece, Etruria, and Rome, and in the Middle Ages through to North Africa as alnafir and, with the Moors, up into Spain as the añafil , and thence into the rest of Europe, and with the Hausa down into Ghana and Nigeria as the kakaki .

According to Al Farabi the Arab ’ud , that became the lute in medieval Europe, also originated there, and so, around the eighth century CE, did the fiddle bow ( Bachmann, 1969 ). Initially, this was a rough stick or reed scraping the string, but it was not long before it was modified with the strands of horsehair that we still use today.

This at last allowed stringed instruments to produce a sustained sound, something that could emulate the human voice, as all wind instruments had been able to do ever since their introduction.

In the early thirteenth century, and probably a little earlier, there came a revolution of the instruments we used in Europe. This seems to have been due to the often-interrupted symbiosis of Moorish, Jewish, and Christian cultures in Spain, and possibly also with some effect from returning Crusaders from the Holy Land. A flood of new instruments appeared, as can be seen in the many miniatures of the Cántigas de Santa Maria , a series of poems written by Alfonso X, called El Sabio, the wise. 4 We see there the Arab ’ud which became our lute, the small bowed fiddle, the rebab , which became our rebec, the reed-blown pipe the zamr , which became our shawm, the ancestor of our oboe, several types of bagpipe, harps with a forepillar, various zithers such as the qanun that became our canon and then the psaltery, the transverse flute, other types of lute that became our gitterns and eventually citterns and guitars, alnafir that became the Spanish añafil and our long trumpet, pipe and tabor, the pipe played with one hand and the tabor struck with the other, which became a standard one-man band from the Middle Ages into the sixteenth century, the timbre, a frame drum that became our tambourine, and the naqqere , two small kettledrums, our nakers, that hung low from the belt in front of the player, and eventually became our timpani. Within the ensuing century, these spread all over western Europe and can be seen in a great many medieval manuscripts, church carvings, and other sources.

We know little of the extent that these played together. There are some group scenes in the Cántigas , but mostly, the miniatures show either one instrument or two of the same sort tuning or playing to each other. We do see large groups of instruments in manuscripts of the following centuries, but these are mostly portrayals of biblical scenes or of texts such as psalm 150 and may not represent anything that actually happened in the Middle Ages.

Then, in the fourteenth century, came another revolution, this time an industrial one ( Gimpel, 1988 ). All over Europe, there had been windmills and watermills, primarily for grinding grain, but often also for minor industrial purposes. Now came the idea of siting watermills under the arches of bridges on major rivers, where the flow of water, restricted by the pillars of the bridge, thus produced far greater force. This powered mills for working metals and, for our purposes, of drawing brass and iron wire to standard quality and in much finer gages than had been available earlier except in softer, and more costly, metals such as silver and gold. The result was strings for harps, psalteries, and dulcimers and thence to keyboard instruments, first the clavichord, which was a keyed development of the monochord, and then the harpsichord. All, as can be seen in the manuscript of Arnault de Zwolle from around 1440, were established by that date ( Le Cerf and Labande, 1932 ).

The use of keyboards led to a revision of musical pitch and tuning. Just Temperament had served well for unaccompanied voices and some solo instruments, but its inadequacies had now become more apparent. If one depends on the partials of the harmonic series, their ratios makes it obvious that the step from 8 to 9 is greater than that of 9 to 10. To avoid using sharps and flats, let us take these pitches as C for 8, D for 9, and E for 10. And for clarity let us use the musicologist’s interval-measuring system of cents, analogous to the general use of millimeters for linear measurement. The major tone of 8–9 is 204 cents; the minor tone of 9–10 is 182 cents, and together these make up the third, C to E, of 386 cents. Now if we want to play in C major, all is well, but if instead, we want to start a scale on D, we are in trouble, for where we need a major tone we have only a minor tone. Voices have no trouble with this for they simply shift the D and the E, but for any instrument with strings such as those of a lyre, a harp, or keyboards, the player has to stop and retune all his strings. The problem was already recognized by the ancient Greeks, and it was allegedly Pythagoras who solved the problem and who decided to make all the wholetones the same size, with 204 cents for each. However, adding those together produces a wildly sharp third of 408 cents from C to E, which when used in a common chord with C and G was so intolerable that in the Middle Ages it was regarded as a dissonance. Thus the Pythagorean Temperament was intolerable on the new keyboard instruments, and the music theorist Pietro Aron devised a new temperament in 1523. He returned to the natural third of 386 cents and, taking its mean or average of 193 cents for each whole tone, created the Quarter-comma Meantone Temperament. To the modern ear, accustomed to the Equal Temperament of our piano, with its wholetones of 200 cents and semitones of 100 cents, these differences may seem small, but if one listens to music played in other temperaments, it really does sound different—even today a 400-cent third still sounds quite badly out of tune. This whole subject is quite complex and Barbour, 1951 , or the article on Temperaments in the New Grove Dictionary of Music , will give fuller details. 5 The basic problem is that the natural fifth of 702 cents is incompatible with the octave of 1200 cents; if one piles up a sequence of fifths, C to G, G to D, D to A and so on, the series will never return to C, only to a B-sharp 22 cents higher than C. Somehow those 22 cents, called a comma, have to be brought back into the octave, and this is done, with greater or lesser success, by using one of the various so-called irregular temperaments.

We have been neglecting vocal music. This has continued unchecked through the ages. When and how choral music, in our modern sense of song, evolved we do not know, but it had certainly appeared by biblical times and by that of the Greek dramatists. While we have mentioned some early suggested musical notations, music was normally taught by rote or simply by listening to others and joining in. What, if any, types of harmony were used, other than singing in octaves, we cannot know for we have no notation system, other than those early ones mentioned above for a basic melody, until we reach the early church chants. Here, we meet Gregorian and other church chants. These appear initially to have been purely monophonic, with everyone singing in unison. The earliest notation, called neumes, shows musical movement rather than precise pitches, and can only have served as a reminder of how music, already learned by rote, was to proceed. What pitch the music started on would depend on the preferred vocal range of the singers. Not until the thirteenth century do we start to see music written on a staff, then usually on only four lines rather than our present five-line stave, and with a symbol to tell us which line is C, similarly to our own alto or tenor clefs.

By the end of the twelfth century, we have composers such as Perotin writing organum, two or more parallel lines a fifth, fourth, or octave apart, with some slight freedom for each line to ornament a little. Organum probably derives from the organ itself, for while the first organs, which appeared in Alexandria in the second century BCE, were purely monophonic, though with the ability to play a chord, the larger church organs of the ninth or tenth centuries CE, used a system called Blockwerk . This meant that each key, when depressed, sounded a chord, a group of fourths or fifths and octaves. We have vivid descriptions of the tenth-century organ of Winchester Cathedral in Britain ( Perrot, 1971 ), and we have surviving pipes from the organ of Bethlehem from the eleventh century of the Latin Kingdom of the Crusaders; the groups of lengths of these pipes show that this organ must also have used Blockwerk ( Montagu, 2005 ).

What about secular music? Here, our earliest manuscripts seem to be from the thirteenth century with Adam de la Halle and his contemporaries writing motets for singers, and with anonymous, usually monophonic, dance music. Early polyphony, music in more than one part, was normally based on a cantus firmus, or tenor, often derived from a church chant, around which other, more elaborate parts, were woven. Polyphony of this sort seems to have been a purely European development; other cultures then, and in many cases still, prefer a single line or monophony, or if singing in groups or a single line with accompaniment, using heterophony, people all singing much, but by no means exactly, the same. Later motets might have three or four independent lines, sometimes each with their own text, woven together. These, in the early Renaissance, led to the madrigals and thence to our various styles of choral music today.

How do we define public performance, and how far back does it go? If one defines it as making music where other people can hear you, it must be as early as music ever existed. Any dance, whether Australian corroborees, war or hunting dances, people dancing on the village green, or any other similar occasions, must have involved music of some sort—how else could people keep their movement together? Here, we return to the use of rhythm, and surely to that of concussion or percussion of some sort, whether just body or hand clapping or that of instruments.

The shaman has always used music of some sort, often to help to throw him- or herself into the necessary trance. The bard has always been a valued member of society—and has always chanted and sung his lays, and always to self-accompaniment on an instrument. All these were “public” performances, either deliberately or at the very least where other people could hear them. At what stage was music deliberately performed to a public? Dance again, of course, and in religious ceremonies. The Christian church could be considered to be the first concert hall, with all free to enter and to hear the chant and, as time went on, listening to the deliberately composed music for the Mass. The medieval mystery plays were enacted in front of or within the church, and these always included music and were designed deliberately to draw in the public and to show them aspects of their religion.

When did people pay to hear music? Surely, this is part of our definition of public performance. Bards were certainly paid, domestic ones with board and lodging and presumably some cash, and itinerant ones certainly with cash or its portable equivalent, and shamans and medicine-men or -women always with cash or its equivalent, for that was the only way to be sure of a cure rather than a curse.

Formal concerts are said to have begun in Italy with the Accademia , meetings of intellectuals and musicians, in the fifteenth century, and private groups of musicians and musically interested people proliferated in many places, coming together to hear their own members playing and/or singing, for example the German Collegia . Aristocratic courts had their own orchestras, often merely for prestige, but sometimes, because the prince was himself a composer and musician. All these were private occasions, with admission confined to their members, their friends, and their guests.