- Locations and Hours

- UCLA Library

- Research Guides

- Biomedical Library Guides

Systematic Reviews

- Types of Literature Reviews

What Makes a Systematic Review Different from Other Types of Reviews?

- Planning Your Systematic Review

- Database Searching

- Creating the Search

- Search Filters and Hedges

- Grey Literature

- Managing and Appraising Results

- Further Resources

Reproduced from Grant, M. J. and Booth, A. (2009), A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information & Libraries Journal, 26: 91–108. doi:10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

| Aims to demonstrate writer has extensively researched literature and critically evaluated its quality. Goes beyond mere description to include degree of analysis and conceptual innovation. Typically results in hypothesis or mode | Seeks to identify most significant items in the field | No formal quality assessment. Attempts to evaluate according to contribution | Typically narrative, perhaps conceptual or chronological | Significant component: seeks to identify conceptual contribution to embody existing or derive new theory | |

| Generic term: published materials that provide examination of recent or current literature. Can cover wide range of subjects at various levels of completeness and comprehensiveness. May include research findings | May or may not include comprehensive searching | May or may not include quality assessment | Typically narrative | Analysis may be chronological, conceptual, thematic, etc. | |

| Mapping review/ systematic map | Map out and categorize existing literature from which to commission further reviews and/or primary research by identifying gaps in research literature | Completeness of searching determined by time/scope constraints | No formal quality assessment | May be graphical and tabular | Characterizes quantity and quality of literature, perhaps by study design and other key features. May identify need for primary or secondary research |

| Technique that statistically combines the results of quantitative studies to provide a more precise effect of the results | Aims for exhaustive, comprehensive searching. May use funnel plot to assess completeness | Quality assessment may determine inclusion/ exclusion and/or sensitivity analyses | Graphical and tabular with narrative commentary | Numerical analysis of measures of effect assuming absence of heterogeneity | |

| Refers to any combination of methods where one significant component is a literature review (usually systematic). Within a review context it refers to a combination of review approaches for example combining quantitative with qualitative research or outcome with process studies | Requires either very sensitive search to retrieve all studies or separately conceived quantitative and qualitative strategies | Requires either a generic appraisal instrument or separate appraisal processes with corresponding checklists | Typically both components will be presented as narrative and in tables. May also employ graphical means of integrating quantitative and qualitative studies | Analysis may characterise both literatures and look for correlations between characteristics or use gap analysis to identify aspects absent in one literature but missing in the other | |

| Generic term: summary of the [medical] literature that attempts to survey the literature and describe its characteristics | May or may not include comprehensive searching (depends whether systematic overview or not) | May or may not include quality assessment (depends whether systematic overview or not) | Synthesis depends on whether systematic or not. Typically narrative but may include tabular features | Analysis may be chronological, conceptual, thematic, etc. | |

| Method for integrating or comparing the findings from qualitative studies. It looks for ‘themes’ or ‘constructs’ that lie in or across individual qualitative studies | May employ selective or purposive sampling | Quality assessment typically used to mediate messages not for inclusion/exclusion | Qualitative, narrative synthesis | Thematic analysis, may include conceptual models | |

| Assessment of what is already known about a policy or practice issue, by using systematic review methods to search and critically appraise existing research | Completeness of searching determined by time constraints | Time-limited formal quality assessment | Typically narrative and tabular | Quantities of literature and overall quality/direction of effect of literature | |

| Preliminary assessment of potential size and scope of available research literature. Aims to identify nature and extent of research evidence (usually including ongoing research) | Completeness of searching determined by time/scope constraints. May include research in progress | No formal quality assessment | Typically tabular with some narrative commentary | Characterizes quantity and quality of literature, perhaps by study design and other key features. Attempts to specify a viable review | |

| Tend to address more current matters in contrast to other combined retrospective and current approaches. May offer new perspectives | Aims for comprehensive searching of current literature | No formal quality assessment | Typically narrative, may have tabular accompaniment | Current state of knowledge and priorities for future investigation and research | |

| Seeks to systematically search for, appraise and synthesis research evidence, often adhering to guidelines on the conduct of a review | Aims for exhaustive, comprehensive searching | Quality assessment may determine inclusion/exclusion | Typically narrative with tabular accompaniment | What is known; recommendations for practice. What remains unknown; uncertainty around findings, recommendations for future research | |

| Combines strengths of critical review with a comprehensive search process. Typically addresses broad questions to produce ‘best evidence synthesis’ | Aims for exhaustive, comprehensive searching | May or may not include quality assessment | Minimal narrative, tabular summary of studies | What is known; recommendations for practice. Limitations | |

| Attempt to include elements of systematic review process while stopping short of systematic review. Typically conducted as postgraduate student assignment | May or may not include comprehensive searching | May or may not include quality assessment | Typically narrative with tabular accompaniment | What is known; uncertainty around findings; limitations of methodology | |

| Specifically refers to review compiling evidence from multiple reviews into one accessible and usable document. Focuses on broad condition or problem for which there are competing interventions and highlights reviews that address these interventions and their results | Identification of component reviews, but no search for primary studies | Quality assessment of studies within component reviews and/or of reviews themselves | Graphical and tabular with narrative commentary | What is known; recommendations for practice. What remains unknown; recommendations for future research |

- << Previous: Home

- Next: Planning Your Systematic Review >>

- Last Updated: Jul 23, 2024 3:40 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.ucla.edu/systematicreviews

Literature Review: Types of literature reviews

- Traditional or narrative literature reviews

- Scoping Reviews

- Systematic literature reviews

- Annotated bibliography

- Keeping up to date with literature

- Finding a thesis

- Evaluating sources and critical appraisal of literature

- Managing and analysing your literature

- Further reading and resources

Types of literature reviews

The type of literature review you write will depend on your discipline and whether you are a researcher writing your PhD, publishing a study in a journal or completing an assessment task in your undergraduate study.

A literature review for a subject in an undergraduate degree will not be as comprehensive as the literature review required for a PhD thesis.

An undergraduate literature review may be in the form of an annotated bibliography or a narrative review of a small selection of literature, for example ten relevant articles. If you are asked to write a literature review, and you are an undergraduate student, be guided by your subject coordinator or lecturer.

The common types of literature reviews will be explained in the pages of this section.

- Narrative or traditional literature reviews

- Critically Appraised Topic (CAT)

- Scoping reviews

- Annotated bibliographies

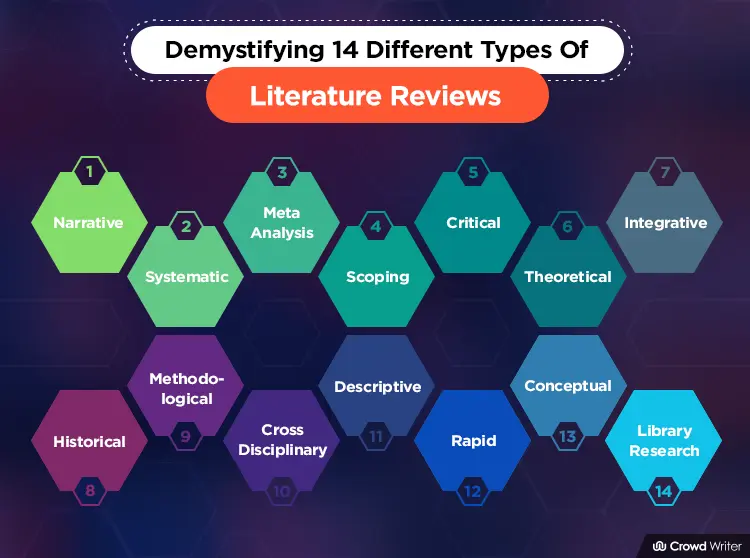

These are not the only types of reviews of literature that can be conducted. Often the term "review" and "literature" can be confusing and used in the wrong context. Grant and Booth (2009) attempt to clear up this confusion by discussing 14 review types and the associated methodology, and advantages and disadvantages associated with each review.

Grant, M. J. and Booth, A. (2009), A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies . Health Information & Libraries Journal, 26 , 91–108. doi:10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

What's the difference between reviews?

Researchers, academics, and librarians all use various terms to describe different types of literature reviews, and there is often inconsistency in the ways the types are discussed. Here are a couple of simple explanations.

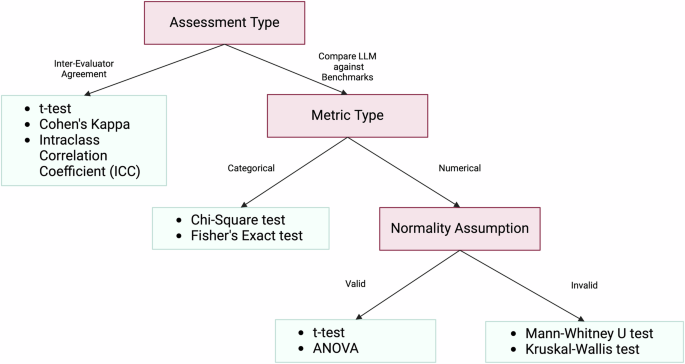

- The image below describes common review types in terms of speed, detail, risk of bias, and comprehensiveness:

"Schematic of the main differences between the types of literature review" by Brennan, M. L., Arlt, S. P., Belshaw, Z., Buckley, L., Corah, L., Doit, H., Fajt, V. R., Grindlay, D., Moberly, H. K., Morrow, L. D., Stavisky, J., & White, C. (2020). Critically Appraised Topics (CATs) in veterinary medicine: Applying evidence in clinical practice. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 7 , 314. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2020.00314 is licensed under CC BY 3.0

- The table below lists four of the most common types of review , as adapted from a widely used typology of fourteen types of reviews (Grant & Booth, 2009).

| Identifies and reviews published literature on a topic, which may be broad. Typically employs a narrative approach to reporting the review findings. Can include a wide range of related subjects. | 1 - 4 weeks | 1 | |

| Assesses what is known about an issue by using a systematic review method to search and appraise research and determine best practice. | 2 - 6 months | 2 | |

| Assesses the potential scope of the research literature on a particular topic. Helps determine gaps in the research. (See the page in this guide on .) | 1 - 4 weeks | 1 - 2 | |

| Seeks to systematically search for, appraise, and synthesise research evidence so as to aid decision-making and determine best practice. Can vary in approach, and is often specific to the type of study, which include studies of effectiveness, qualitative research, economic evaluation, prevalence, aetiology, or diagnostic test accuracy. | 8 months to 2 years | 2 or more |

Grant, M.J. & Booth, A. (2009). A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information & Libraries Journal, 26 (2), 91-108. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

See also the Library's Literature Review guide.

Critical Appraised Topic (CAT)

For information on conducting a Critically Appraised Topic or CAT

Callander, J., Anstey, A. V., Ingram, J. R., Limpens, J., Flohr, C., & Spuls, P. I. (2017). How to write a Critically Appraised Topic: evidence to underpin routine clinical practice. British Journal of Dermatology (1951), 177(4), 1007-1013. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.15873

Books on Literature Reviews

- << Previous: Home

- Next: Traditional or narrative literature reviews >>

- Last Updated: Aug 11, 2024 4:07 PM

- URL: https://libguides.csu.edu.au/review

Charles Sturt University is an Australian University, TEQSA Provider Identification: PRV12018. CRICOS Provider: 00005F.

Types of Literature Review

There are many types of literature review. The choice of a specific type depends on your research approach and design. The following types of literature review are the most popular in business studies:

Narrative literature review , also referred to as traditional literature review, critiques literature and summarizes the body of a literature. Narrative review also draws conclusions about the topic and identifies gaps or inconsistencies in a body of knowledge. You need to have a sufficiently focused research question to conduct a narrative literature review

Systematic literature review requires more rigorous and well-defined approach compared to most other types of literature review. Systematic literature review is comprehensive and details the timeframe within which the literature was selected. Systematic literature review can be divided into two categories: meta-analysis and meta-synthesis.

When you conduct meta-analysis you take findings from several studies on the same subject and analyze these using standardized statistical procedures. In meta-analysis patterns and relationships are detected and conclusions are drawn. Meta-analysis is associated with deductive research approach.

Meta-synthesis, on the other hand, is based on non-statistical techniques. This technique integrates, evaluates and interprets findings of multiple qualitative research studies. Meta-synthesis literature review is conducted usually when following inductive research approach.

Scoping literature review , as implied by its name is used to identify the scope or coverage of a body of literature on a given topic. It has been noted that “scoping reviews are useful for examining emerging evidence when it is still unclear what other, more specific questions can be posed and valuably addressed by a more precise systematic review.” [1] The main difference between systematic and scoping types of literature review is that, systematic literature review is conducted to find answer to more specific research questions, whereas scoping literature review is conducted to explore more general research question.

Argumentative literature review , as the name implies, examines literature selectively in order to support or refute an argument, deeply imbedded assumption, or philosophical problem already established in the literature. It should be noted that a potential for bias is a major shortcoming associated with argumentative literature review.

Integrative literature review reviews , critiques, and synthesizes secondary data about research topic in an integrated way such that new frameworks and perspectives on the topic are generated. If your research does not involve primary data collection and data analysis, then using integrative literature review will be your only option.

Theoretical literature review focuses on a pool of theory that has accumulated in regard to an issue, concept, theory, phenomena. Theoretical literature reviews play an instrumental role in establishing what theories already exist, the relationships between them, to what degree existing theories have been investigated, and to develop new hypotheses to be tested.

At the earlier parts of the literature review chapter, you need to specify the type of your literature review your chose and justify your choice. Your choice of a specific type of literature review should be based upon your research area, research problem and research methods. Also, you can briefly discuss other most popular types of literature review mentioned above, to illustrate your awareness of them.

[1] Munn, A. et. al. (2018) “Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach” BMC Medical Research Methodology

John Dudovskiy

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

Published on January 2, 2023 by Shona McCombes . Revised on September 11, 2023.

What is a literature review? A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources on a specific topic. It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant theories, methods, and gaps in the existing research that you can later apply to your paper, thesis, or dissertation topic .

There are five key steps to writing a literature review:

- Search for relevant literature

- Evaluate sources

- Identify themes, debates, and gaps

- Outline the structure

- Write your literature review

A good literature review doesn’t just summarize sources—it analyzes, synthesizes , and critically evaluates to give a clear picture of the state of knowledge on the subject.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

What is the purpose of a literature review, examples of literature reviews, step 1 – search for relevant literature, step 2 – evaluate and select sources, step 3 – identify themes, debates, and gaps, step 4 – outline your literature review’s structure, step 5 – write your literature review, free lecture slides, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions, introduction.

- Quick Run-through

- Step 1 & 2

When you write a thesis , dissertation , or research paper , you will likely have to conduct a literature review to situate your research within existing knowledge. The literature review gives you a chance to:

- Demonstrate your familiarity with the topic and its scholarly context

- Develop a theoretical framework and methodology for your research

- Position your work in relation to other researchers and theorists

- Show how your research addresses a gap or contributes to a debate

- Evaluate the current state of research and demonstrate your knowledge of the scholarly debates around your topic.

Writing literature reviews is a particularly important skill if you want to apply for graduate school or pursue a career in research. We’ve written a step-by-step guide that you can follow below.

Don't submit your assignments before you do this

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students. Free citation check included.

Try for free

Writing literature reviews can be quite challenging! A good starting point could be to look at some examples, depending on what kind of literature review you’d like to write.

- Example literature review #1: “Why Do People Migrate? A Review of the Theoretical Literature” ( Theoretical literature review about the development of economic migration theory from the 1950s to today.)

- Example literature review #2: “Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines” ( Methodological literature review about interdisciplinary knowledge acquisition and production.)

- Example literature review #3: “The Use of Technology in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Thematic literature review about the effects of technology on language acquisition.)

- Example literature review #4: “Learners’ Listening Comprehension Difficulties in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Chronological literature review about how the concept of listening skills has changed over time.)

You can also check out our templates with literature review examples and sample outlines at the links below.

Download Word doc Download Google doc

Before you begin searching for literature, you need a clearly defined topic .

If you are writing the literature review section of a dissertation or research paper, you will search for literature related to your research problem and questions .

Make a list of keywords

Start by creating a list of keywords related to your research question. Include each of the key concepts or variables you’re interested in, and list any synonyms and related terms. You can add to this list as you discover new keywords in the process of your literature search.

- Social media, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, TikTok

- Body image, self-perception, self-esteem, mental health

- Generation Z, teenagers, adolescents, youth

Search for relevant sources

Use your keywords to begin searching for sources. Some useful databases to search for journals and articles include:

- Your university’s library catalogue

- Google Scholar

- Project Muse (humanities and social sciences)

- Medline (life sciences and biomedicine)

- EconLit (economics)

- Inspec (physics, engineering and computer science)

You can also use boolean operators to help narrow down your search.

Make sure to read the abstract to find out whether an article is relevant to your question. When you find a useful book or article, you can check the bibliography to find other relevant sources.

You likely won’t be able to read absolutely everything that has been written on your topic, so it will be necessary to evaluate which sources are most relevant to your research question.

For each publication, ask yourself:

- What question or problem is the author addressing?

- What are the key concepts and how are they defined?

- What are the key theories, models, and methods?

- Does the research use established frameworks or take an innovative approach?

- What are the results and conclusions of the study?

- How does the publication relate to other literature in the field? Does it confirm, add to, or challenge established knowledge?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the research?

Make sure the sources you use are credible , and make sure you read any landmark studies and major theories in your field of research.

You can use our template to summarize and evaluate sources you’re thinking about using. Click on either button below to download.

Take notes and cite your sources

As you read, you should also begin the writing process. Take notes that you can later incorporate into the text of your literature review.

It is important to keep track of your sources with citations to avoid plagiarism . It can be helpful to make an annotated bibliography , where you compile full citation information and write a paragraph of summary and analysis for each source. This helps you remember what you read and saves time later in the process.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

To begin organizing your literature review’s argument and structure, be sure you understand the connections and relationships between the sources you’ve read. Based on your reading and notes, you can look for:

- Trends and patterns (in theory, method or results): do certain approaches become more or less popular over time?

- Themes: what questions or concepts recur across the literature?

- Debates, conflicts and contradictions: where do sources disagree?

- Pivotal publications: are there any influential theories or studies that changed the direction of the field?

- Gaps: what is missing from the literature? Are there weaknesses that need to be addressed?

This step will help you work out the structure of your literature review and (if applicable) show how your own research will contribute to existing knowledge.

- Most research has focused on young women.

- There is an increasing interest in the visual aspects of social media.

- But there is still a lack of robust research on highly visual platforms like Instagram and Snapchat—this is a gap that you could address in your own research.

There are various approaches to organizing the body of a literature review. Depending on the length of your literature review, you can combine several of these strategies (for example, your overall structure might be thematic, but each theme is discussed chronologically).

Chronological

The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time. However, if you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order.

Try to analyze patterns, turning points and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred.

If you have found some recurring central themes, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic.

For example, if you are reviewing literature about inequalities in migrant health outcomes, key themes might include healthcare policy, language barriers, cultural attitudes, legal status, and economic access.

Methodological

If you draw your sources from different disciplines or fields that use a variety of research methods , you might want to compare the results and conclusions that emerge from different approaches. For example:

- Look at what results have emerged in qualitative versus quantitative research

- Discuss how the topic has been approached by empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the literature into sociological, historical, and cultural sources

Theoretical

A literature review is often the foundation for a theoretical framework . You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts.

You might argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach, or combine various theoretical concepts to create a framework for your research.

Like any other academic text , your literature review should have an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion . What you include in each depends on the objective of your literature review.

The introduction should clearly establish the focus and purpose of the literature review.

Depending on the length of your literature review, you might want to divide the body into subsections. You can use a subheading for each theme, time period, or methodological approach.

As you write, you can follow these tips:

- Summarize and synthesize: give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: don’t just paraphrase other researchers — add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically evaluate: mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: use transition words and topic sentences to draw connections, comparisons and contrasts

In the conclusion, you should summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance.

When you’ve finished writing and revising your literature review, don’t forget to proofread thoroughly before submitting. Not a language expert? Check out Scribbr’s professional proofreading services !

This article has been adapted into lecture slides that you can use to teach your students about writing a literature review.

Scribbr slides are free to use, customize, and distribute for educational purposes.

Open Google Slides Download PowerPoint

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a thesis, dissertation , or research paper , in order to situate your work in relation to existing knowledge.

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarize yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

The literature review usually comes near the beginning of your thesis or dissertation . After the introduction , it grounds your research in a scholarly field and leads directly to your theoretical framework or methodology .

A literature review is a survey of credible sources on a topic, often used in dissertations , theses, and research papers . Literature reviews give an overview of knowledge on a subject, helping you identify relevant theories and methods, as well as gaps in existing research. Literature reviews are set up similarly to other academic texts , with an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion .

An annotated bibliography is a list of source references that has a short description (called an annotation ) for each of the sources. It is often assigned as part of the research process for a paper .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, September 11). How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates. Scribbr. Retrieved September 27, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/literature-review/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is a research methodology | steps & tips, how to write a research proposal | examples & templates, get unlimited documents corrected.

✔ Free APA citation check included ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

- UConn Library

- Literature Review: The What, Why and How-to Guide

- Introduction

Literature Review: The What, Why and How-to Guide — Introduction

- Getting Started

- How to Pick a Topic

- Strategies to Find Sources

- Evaluating Sources & Lit. Reviews

- Tips for Writing Literature Reviews

- Writing Literature Review: Useful Sites

- Citation Resources

- Other Academic Writings

What are Literature Reviews?

So, what is a literature review? "A literature review is an account of what has been published on a topic by accredited scholars and researchers. In writing the literature review, your purpose is to convey to your reader what knowledge and ideas have been established on a topic, and what their strengths and weaknesses are. As a piece of writing, the literature review must be defined by a guiding concept (e.g., your research objective, the problem or issue you are discussing, or your argumentative thesis). It is not just a descriptive list of the material available, or a set of summaries." Taylor, D. The literature review: A few tips on conducting it . University of Toronto Health Sciences Writing Centre.

Goals of Literature Reviews

What are the goals of creating a Literature Review? A literature could be written to accomplish different aims:

- To develop a theory or evaluate an existing theory

- To summarize the historical or existing state of a research topic

- Identify a problem in a field of research

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1997). Writing narrative literature reviews . Review of General Psychology , 1 (3), 311-320.

What kinds of sources require a Literature Review?

- A research paper assigned in a course

- A thesis or dissertation

- A grant proposal

- An article intended for publication in a journal

All these instances require you to collect what has been written about your research topic so that you can demonstrate how your own research sheds new light on the topic.

Types of Literature Reviews

What kinds of literature reviews are written?

Narrative review: The purpose of this type of review is to describe the current state of the research on a specific topic/research and to offer a critical analysis of the literature reviewed. Studies are grouped by research/theoretical categories, and themes and trends, strengths and weakness, and gaps are identified. The review ends with a conclusion section which summarizes the findings regarding the state of the research of the specific study, the gaps identify and if applicable, explains how the author's research will address gaps identify in the review and expand the knowledge on the topic reviewed.

- Example : Predictors and Outcomes of U.S. Quality Maternity Leave: A Review and Conceptual Framework: 10.1177/08948453211037398

Systematic review : "The authors of a systematic review use a specific procedure to search the research literature, select the studies to include in their review, and critically evaluate the studies they find." (p. 139). Nelson, L. K. (2013). Research in Communication Sciences and Disorders . Plural Publishing.

- Example : The effect of leave policies on increasing fertility: a systematic review: 10.1057/s41599-022-01270-w

Meta-analysis : "Meta-analysis is a method of reviewing research findings in a quantitative fashion by transforming the data from individual studies into what is called an effect size and then pooling and analyzing this information. The basic goal in meta-analysis is to explain why different outcomes have occurred in different studies." (p. 197). Roberts, M. C., & Ilardi, S. S. (2003). Handbook of Research Methods in Clinical Psychology . Blackwell Publishing.

- Example : Employment Instability and Fertility in Europe: A Meta-Analysis: 10.1215/00703370-9164737

Meta-synthesis : "Qualitative meta-synthesis is a type of qualitative study that uses as data the findings from other qualitative studies linked by the same or related topic." (p.312). Zimmer, L. (2006). Qualitative meta-synthesis: A question of dialoguing with texts . Journal of Advanced Nursing , 53 (3), 311-318.

- Example : Women’s perspectives on career successes and barriers: A qualitative meta-synthesis: 10.1177/05390184221113735

Literature Reviews in the Health Sciences

- UConn Health subject guide on systematic reviews Explanation of the different review types used in health sciences literature as well as tools to help you find the right review type

- << Previous: Getting Started

- Next: How to Pick a Topic >>

- Last Updated: Sep 21, 2022 2:16 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.uconn.edu/literaturereview

- Chester Fritz Library

- Library of the Health Sciences

- Thormodsgard Law Library

Literature Reviews

- Get started

Literature Reviews within a Scholarly Work

Literature reviews as a scholarly work.

- Finding Literature Reviews

- Your Literature Search

- Library Books

- How to Videos

- Communicating & Citing Research

- Bibliography

Literature reviews summarize and analyze what has been written on a particular topic and identify gaps or disagreements in the scholarly work on that topic.

Within a scholarly work, the literature review situates the current work within the larger scholarly conversation and emphasizes how that particular scholarly work contributes to the conversation on the topic. The literature review portion may be as brief as a few paragraphs focusing on a narrow topic area.

When writing this type of literature review, it's helpful to start by identifying sources most relevant to your research question. A citation tracking database such as Web of Science can also help you locate seminal articles on a topic and find out who has more recently cited them. See "Your Literature Search" for more details.

A literature review may itself be a scholarly publication and provide an analysis of what has been written on a particular topic without contributing original research. These types of literature reviews can serve to help keep people updated on a field as well as helping scholars choose a research topic to fill gaps in the knowledge on that topic. Common types include:

Systematic Review

Systematic literature reviews follow specific procedures in some ways similar to setting up an experiment to ensure that future scholars can replicate the same steps. They are also helpful for evaluating data published over multiple studies. Thus, these are common in the medical field and may be used by healthcare providers to help guide diagnosis and treatment decisions. Cochrane Reviews are one example of this type of literature review.

Semi-Systematic Review

When a systematic review is not feasible, a semi-systematic review can help synthesize research on a topic or how a topic has been studied in different fields (Snyder 2019). Rather than focusing on quantitative data, this review type identifies themes, theoretical perspectives, and other qualitative information related to the topic. These types of reviews can be particularly helpful for a historical topic overview, for developing a theoretical model, and for creating a research agenda for a field (Snyder 2019). As with systematic reviews, a search strategy must be developed before conducting the review.

Integrative Review

An integrative review is less systematic and can be helpful for developing a theoretical model or to reconceptualize a topic. As Synder (2019) notes, " This type of review often re quires a more creative collection of data, as the purpose is usually not to cover all articles ever published on the topic but rather to combine perspectives and insights from di ff erent fi elds or research traditions" (p. 336).

| Sythesize and compare evidence | Quantitative, comprehensive for specific area, systematic search strategy, informs policy/practice | Health sciences, social sciences, STEM | |

| Overview research area & changes over time | Quantitative or qualitative, less detailed/thorough search strategy, identifies themes or research gaps or develops a theoretical model or provides a history of the field | All | |

| Synthesize literature to develop new perspectives or theories | Qualitative, non-systematic search strategy, combines ideas from different fields, focus on creating new frameworks or theories by critiquing previous ideas | Social sciences, humanities |

Source: Snyder, H. (2019). Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines. Journal of Business Research. 104. 333-339. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.07.039

- << Previous: Get started

- Next: Finding Literature Reviews >>

- Last Updated: Sep 6, 2024 5:10 PM

- URL: https://libguides.und.edu/literature-reviews

Literature Reviews

- Types of reviews

- Getting started

Types of reviews and examples

Choosing a review type.

- 1. Define your research question

- 2. Plan your search

- 3. Search the literature

- 4. Organize your results

- 5. Synthesize your findings

- 6. Write the review

- Artificial intelligence (AI) tools

- Thompson Writing Studio This link opens in a new window

- Need to write a systematic review? This link opens in a new window

Contact a Librarian

Ask a Librarian

- Meta-analysis

- Systematized

Definition:

"A term used to describe a conventional overview of the literature, particularly when contrasted with a systematic review (Booth et al., 2012, p. 265).

Characteristics:

- Provides examination of recent or current literature on a wide range of subjects

- Varying levels of completeness / comprehensiveness, non-standardized methodology

- May or may not include comprehensive searching, quality assessment or critical appraisal

Mitchell, L. E., & Zajchowski, C. A. (2022). The history of air quality in Utah: A narrative review. Sustainability , 14 (15), 9653. doi.org/10.3390/su14159653

Booth, A., Papaioannou, D., & Sutton, A. (2012). Systematic approaches to a successful literature review. London: SAGE Publications Ltd.

"An assessment of what is already known about a policy or practice issue...using systematic review methods to search and critically appraise existing research" (Grant & Booth, 2009, p. 100).

- Assessment of what is already known about an issue

- Similar to a systematic review but within a time-constrained setting

- Typically employs methodological shortcuts, increasing risk of introducing bias, includes basic level of quality assessment

- Best suited for issues needing quick decisions and solutions (i.e., policy recommendations)

Learn more about the method:

Khangura, S., Konnyu, K., Cushman, R., Grimshaw, J., & Moher, D. (2012). Evidence summaries: the evolution of a rapid review approach. Systematic reviews, 1 (1), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-1-10

Virginia Commonwealth University Libraries. (2021). Rapid Review Protocol .

Quarmby, S., Santos, G., & Mathias, M. (2019). Air quality strategies and technologies: A rapid review of the international evidence. Sustainability, 11 (10), 2757. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11102757

Grant, M.J. & Booth, A. (2009). A typology of reviews: an analysis of the 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information & Libraries Journal , 26(2), 91-108. https://www.doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

Developed and refined by the Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Co-ordinating Centre (EPPI-Centre), this review "map[s] out and categorize[s] existing literature on a particular topic, identifying gaps in research literature from which to commission further reviews and/or primary research" (Grant & Booth, 2009, p. 97).

Although mapping reviews are sometimes called scoping reviews, the key difference is that mapping reviews focus on a review question, rather than a topic

Mapping reviews are "best used where a clear target for a more focused evidence product has not yet been identified" (Booth, 2016, p. 14)

Mapping review searches are often quick and are intended to provide a broad overview

Mapping reviews can take different approaches in what types of literature is focused on in the search

Cooper I. D. (2016). What is a "mapping study?". Journal of the Medical Library Association: JMLA , 104 (1), 76–78. https://doi.org/10.3163/1536-5050.104.1.013

Miake-Lye, I. M., Hempel, S., Shanman, R., & Shekelle, P. G. (2016). What is an evidence map? A systematic review of published evidence maps and their definitions, methods, and products. Systematic reviews, 5 (1), 1-21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0204-x

Tainio, M., Andersen, Z. J., Nieuwenhuijsen, M. J., Hu, L., De Nazelle, A., An, R., ... & de Sá, T. H. (2021). Air pollution, physical activity and health: A mapping review of the evidence. Environment international , 147 , 105954. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2020.105954

Booth, A. (2016). EVIDENT Guidance for Reviewing the Evidence: a compendium of methodological literature and websites . ResearchGate. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.1.1562.9842 .

Grant, M.J. & Booth, A. (2009). A typology of reviews: an analysis of the 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information & Libraries Journal , 26(2), 91-108. https://www.doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

"A type of review that has as its primary objective the identification of the size and quality of research in a topic area in order to inform subsequent review" (Booth et al., 2012, p. 269).

- Main purpose is to map out and categorize existing literature, identify gaps in literature—great for informing policy-making

- Search comprehensiveness determined by time/scope constraints, could take longer than a systematic review

- No formal quality assessment or critical appraisal

Learn more about the methods :

Arksey, H., & O'Malley, L. (2005) Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology , 8 (1), 19-32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

Levac, D., Colquhoun, H., & O’Brien, K. K. (2010). Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science: IS, 5, 69. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-69

Example :

Rahman, A., Sarkar, A., Yadav, O. P., Achari, G., & Slobodnik, J. (2021). Potential human health risks due to environmental exposure to nano-and microplastics and knowledge gaps: A scoping review. Science of the Total Environment, 757 , 143872. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.143872

A review that "[compiles] evidence from multiple...reviews into one accessible and usable document" (Grant & Booth, 2009, p. 103). While originally intended to be a compilation of Cochrane reviews, it now generally refers to any kind of evidence synthesis.

- Compiles evidence from multiple reviews into one document

- Often defines a broader question than is typical of a traditional systematic review

Choi, G. J., & Kang, H. (2022). The umbrella review: a useful strategy in the rain of evidence. The Korean Journal of Pain , 35 (2), 127–128. https://doi.org/10.3344/kjp.2022.35.2.127

Aromataris, E., Fernandez, R., Godfrey, C. M., Holly, C., Khalil, H., & Tungpunkom, P. (2015). Summarizing systematic reviews: Methodological development, conduct and reporting of an umbrella review approach. International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare , 13(3), 132–140. https://doi.org/10.1097/XEB.0000000000000055

Rojas-Rueda, D., Morales-Zamora, E., Alsufyani, W. A., Herbst, C. H., Al Balawi, S. M., Alsukait, R., & Alomran, M. (2021). Environmental risk factors and health: An umbrella review of meta-analyses. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Dealth , 18 (2), 704. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18020704

A meta-analysis is a "technique that statistically combines the results of quantitative studies to provide a more precise effect of the result" (Grant & Booth, 2009, p. 98).

- Statistical technique for combining results of quantitative studies to provide more precise effect of results

- Aims for exhaustive, comprehensive searching

- Quality assessment may determine inclusion/exclusion criteria

- May be conducted independently or as part of a systematic review

Berman, N. G., & Parker, R. A. (2002). Meta-analysis: Neither quick nor easy. BMC Medical Research Methodology , 2(1), 10. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-2-10

Hites R. A. (2004). Polybrominated diphenyl ethers in the environment and in people: a meta-analysis of concentrations. Environmental Science & Technology , 38 (4), 945–956. https://doi.org/10.1021/es035082g

A systematic review "seeks to systematically search for, appraise, and [synthesize] research evidence, often adhering to the guidelines on the conduct of a review" provided by discipline-specific organizations, such as the Cochrane Collaboration (Grant & Booth, 2009, p. 102).

- Aims to compile and synthesize all known knowledge on a given topic

- Adheres to strict guidelines, protocols, and frameworks

- Time-intensive and often takes months to a year or more to complete

- The most commonly referred to type of evidence synthesis. Sometimes confused as a blanket term for other types of reviews

Gascon, M., Triguero-Mas, M., Martínez, D., Dadvand, P., Forns, J., Plasència, A., & Nieuwenhuijsen, M. J. (2015). Mental health benefits of long-term exposure to residential green and blue spaces: a systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health , 12 (4), 4354–4379. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph120404354

"Systematized reviews attempt to include one or more elements of the systematic review process while stopping short of claiming that the resultant output is a systematic review" (Grant & Booth, 2009, p. 102). When a systematic review approach is adapted to produce a more manageable scope, while still retaining the rigor of a systematic review such as risk of bias assessment and the use of a protocol, this is often referred to as a structured review (Huelin et al., 2015).

- Typically conducted by postgraduate or graduate students

- Often assigned by instructors to students who don't have the resources to conduct a full systematic review

Salvo, G., Lashewicz, B. M., Doyle-Baker, P. K., & McCormack, G. R. (2018). Neighbourhood built environment influences on physical activity among adults: A systematized review of qualitative evidence. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health , 15 (5), 897. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15050897

Huelin, R., Iheanacho, I., Payne, K., & Sandman, K. (2015). What’s in a name? Systematic and non-systematic literature reviews, and why the distinction matters. https://www.evidera.com/resource/whats-in-a-name-systematic-and-non-systematic-literature-reviews-and-why-the-distinction-matters/

- Review Decision Tree - Cornell University For more information, check out Cornell's review methodology decision tree.

- LitR-Ex.com - Eight literature review methodologies Learn more about 8 different review types (incl. Systematic Reviews and Scoping Reviews) with practical tips about strengths and weaknesses of different methods.

- << Previous: Getting started

- Next: 1. Define your research question >>

- Last Updated: Sep 17, 2024 1:24 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.duke.edu/litreviews

Services for...

- Faculty & Instructors

- Graduate Students

- Undergraduate Students

- International Students

- Patrons with Disabilities

- Harmful Language Statement

- Re-use & Attribution / Privacy

- Support the Libraries

- University of Wisconsin–Madison

- University of Wisconsin-Madison

- Research Guides

- Evidence Synthesis, Systematic Review Services

- Literature Review Types, Taxonomies

Evidence Synthesis, Systematic Review Services : Literature Review Types, Taxonomies

- Develop a Protocol

- Develop Your Research Question

- Select Databases

- Select Gray Literature Sources

- Write a Search Strategy

- Manage Your Search Process

- Register Your Protocol

- Citation Management

- Article Screening

- Risk of Bias Assessment

- Synthesize, Map, or Describe the Results

- Find Guidance by Discipline

- Manage Your Research Data

- Browse Evidence Portals by Discipline

- Automate the Process, Tools & Technologies

- Adapting Systematic Review Methods

- Additional Resources

Choosing a Literature Review Methodology

Growing interest in evidence-based practice has driven an increase in review methodologies. Your choice of review methodology (or literature review type) will be informed by the intent (purpose, function) of your research project and the time and resources of your team.

- Decision Tree (What Type of Review is Right for You?) Developed by Cornell University Library staff, this "decision-tree" guides the user to a handful of review guides given time and intent.

Types of Evidence Synthesis*

Critical Review - Aims to demonstrate writer has extensively researched literature and critically evaluated its quality. Goes beyond mere description to include degree of analysis and conceptual innovation. Typically results in hypothesis or model.

Mapping Review (Systematic Map) - Map out and categorize existing literature from which to commission further reviews and/or primary research by identifying gaps in research literature.

Meta-Analysis - Technique that statistically combines the results of quantitative studies to provide a more precise effect of the results.

Mixed Studies Review (Mixed Methods Review) - Refers to any combination of methods where one significant component is a literature review (usually systematic). Within a review context it refers to a combination of review approaches for example combining quantitative with qualitative research or outcome with process studies.

Narrative (Literature) Review - Broad, generic term - Refers to an examination and general synthesis of the research literature, often with a wide scope; completeness and comprehensiveness may vary. Does not follow an established protocol.

Overview - Generic term: summary of the [medical] literature that attempts to survey the literature and describe its characteristics.

Qualitative Systematic Review or Qualitative Evidence Synthesis - Method for integrating or comparing the findings from qualitative studies. It looks for ‘themes’ or ‘constructs’ that lie in or across individual qualitative studies.

Rapid Review - Assessment of what is already known about a policy or practice issue, by using systematic review methods to search and critically appraise existing research.

Scoping Review or Evidence Map - Preliminary assessment of potential size and scope of available research literature. Aims to identify nature and extent of research.

State-of-the-art Review - Tend to address more current matters in contrast to other combined retrospective and current approaches. May offer new perspectives on issue or point out area for further research.

Systematic Review - Seeks to systematically search for, appraise and synthesize research evidence, often adhering to guidelines on the conduct of a review. (An emerging subset includes Living Reviews or Living Systematic Reviews - A [review or] systematic review which is continually updated, incorporating relevant new evidence as it becomes available.)

Systematic Search and Review - Combines strengths of critical review with a comprehensive search process. Typically addresses broad questions to produce ‘best evidence synthesis.’

Umbrella Review - Specifically refers to review compiling evidence from multiple reviews into one accessible and usable document. Focuses on broad condition or problem for which there are competing interventions and highlights reviews that address these interventions and their results.

*Apart from some qualifying description for "Narrative (Literature) Review", these definitions are provided in Grant & Booth's "A Typology of Reviews: An Analysis of 14 Review Types and Associated Methodologies."

Literature Review Types/Typologies, Taxonomies

Grant, M. J., and A. Booth. "A Typology of Reviews: An Analysis of 14 Review Types and Associated Methodologies." Health Information and Libraries Journal 26.2 (2009): 91-108. DOI: 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x Link

Munn, Zachary, et al. “Systematic Review or Scoping Review? Guidance for Authors When Choosing between a Systematic or Scoping Review Approach.” BMC Medical Research Methodology , vol. 18, no. 1, Nov. 2018, p. 143. DOI: 10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x. Link

Sutton, A., et al. "Meeting the Review Family: Exploring Review Types and Associated Information Retrieval Requirements." Health Information and Libraries Journal 36.3 (2019): 202-22. DOI: 10.1111/hir.12276 Link

- << Previous: Home

- Next: The Systematic Review Process >>

- Last Updated: Sep 27, 2024 11:50 AM

- URL: https://researchguides.library.wisc.edu/literature_review

Literature Reviews

- Getting Started

Selecting a Review Type

Defining the scope of your review, four common types of reviews.

- Developing a Research Question

- Searching the Literature

- Searching Tips

- ChatGPT [beta]

- Documenting your Search

- Using Citation Managers

- Concept Mapping

- Writing the Review

- Further Resources

More Review Types

This article by Sutton & Booth (2019) explores 48 distinct types of Literature Reviews:

Which Review is Right for You?

The Right Review tool has questions about your lit review process and plans. It offers a qualitative and quantitative option. At completion, you are given a lit review type recommendation.

You'll want to think about the kind of review you are doing. Is it a selective or comprehensive review? Is the review part of a larger work or a stand-alone work ?

For example, if you're writing the Literature Review section of a journal article, that's a selective review which is part of a larger work. Alternatively, if you're writing a review article, that's a comprehensive review which is a stand-alone work. Thinking about this will help you develop the scope of the review.

This exercise will help define the scope of your Literature Review, setting the boundaries for which literature to include and which to exclude.

A FEW GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS WHEN DEFINING SCOPE

- Which populations to investigate — this can include gender, age, socio-economic status, race, geographic location, etc., if the research area includes humans.

- What years to include — if researching the legalization of medicinal cannabis, you might only look at the previous 20 years; but if researching dolphin mating practices, you might extend many more decades.

- Which subject areas — if researching artificial intelligence, subject areas could be computer science, robotics, or health sciences

- How many sources — a selective review for a class assignment might only need ten, while a comprehensive review for a dissertation might include hundreds. There is no one right answer.

- There will be many other considerations that are more specific to your topic.

Most databases will allow you to limit years and subject areas, so look for those tools while searching. See the Searching Tips tab for information on how use these tools.

LITERATURE REVIEW

- Often used as a generic term to describe any type of review

- More precise definition: Published materials that provide an examination of published literature . Can cover wide range of subjects at various levels of comprehensiveness.

- Identifies gaps in research, explains importance of topic, hypothesizes future work, etc.

- Usually written as part of a larger work like a journal article or dissertation

SCOPING REVIEW

- Conducted to address broad research questions with the goal of understanding the extent of research that has been conducted.

- Provides a preliminary assessment of the potential size and scope of available research literature. It aims to identify the nature and extent of research evidence (usually including ongoing research)

- Doesn't assess the quality of the literature gathered (i.e. presence of literature on a topic shouldn’t be conflated w/ the quality of that literature)

- " Preparing scoping reviews for publication using methodological guides and reporting standards " is a great article to read on Scoping Reviews

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW

- Common in the health sciences ( Taubman Health Sciences Library guide to Systematic Reviews )

- Goal: collect all literature that meets specific criteria (methodology, population, treatment, etc.) and then appraise its quality and synthesize it

- Follows strict protocol for literature collection, appraisal and synthesis

- Typically performed by research teams

- Takes 12-18 months to complete

- Often written as a stand alone work

META-ANALYSIS

- Goes one step further than a systematic review by statistically combining the results of quantitative studies to provide a more precise effect of the results.

- << Previous: Getting Started

- Next: Developing a Research Question >>

- Last Updated: Sep 17, 2024 12:03 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.umich.edu/litreview

Harvey Cushing/John Hay Whitney Medical Library

- Collections

- Research Help

YSN Doctoral Programs: Steps in Conducting a Literature Review

- Biomedical Databases

- Global (Public Health) Databases

- Soc. Sci., History, and Law Databases

- Grey Literature

- Trials Registers

- Data and Statistics

- Public Policy

- Google Tips

- Recommended Books

- Steps in Conducting a Literature Review

What is a literature review?

A literature review is an integrated analysis -- not just a summary-- of scholarly writings and other relevant evidence related directly to your research question. That is, it represents a synthesis of the evidence that provides background information on your topic and shows a association between the evidence and your research question.

A literature review may be a stand alone work or the introduction to a larger research paper, depending on the assignment. Rely heavily on the guidelines your instructor has given you.

Why is it important?

A literature review is important because it:

- Explains the background of research on a topic.

- Demonstrates why a topic is significant to a subject area.

- Discovers relationships between research studies/ideas.

- Identifies major themes, concepts, and researchers on a topic.

- Identifies critical gaps and points of disagreement.

- Discusses further research questions that logically come out of the previous studies.

APA7 Style resources

APA Style Blog - for those harder to find answers

1. Choose a topic. Define your research question.

Your literature review should be guided by your central research question. The literature represents background and research developments related to a specific research question, interpreted and analyzed by you in a synthesized way.

- Make sure your research question is not too broad or too narrow. Is it manageable?

- Begin writing down terms that are related to your question. These will be useful for searches later.

- If you have the opportunity, discuss your topic with your professor and your class mates.

2. Decide on the scope of your review

How many studies do you need to look at? How comprehensive should it be? How many years should it cover?

- This may depend on your assignment. How many sources does the assignment require?

3. Select the databases you will use to conduct your searches.

Make a list of the databases you will search.

Where to find databases:

- use the tabs on this guide

- Find other databases in the Nursing Information Resources web page

- More on the Medical Library web page

- ... and more on the Yale University Library web page

4. Conduct your searches to find the evidence. Keep track of your searches.

- Use the key words in your question, as well as synonyms for those words, as terms in your search. Use the database tutorials for help.

- Save the searches in the databases. This saves time when you want to redo, or modify, the searches. It is also helpful to use as a guide is the searches are not finding any useful results.

- Review the abstracts of research studies carefully. This will save you time.

- Use the bibliographies and references of research studies you find to locate others.

- Check with your professor, or a subject expert in the field, if you are missing any key works in the field.

- Ask your librarian for help at any time.

- Use a citation manager, such as EndNote as the repository for your citations. See the EndNote tutorials for help.

Review the literature

Some questions to help you analyze the research:

- What was the research question of the study you are reviewing? What were the authors trying to discover?

- Was the research funded by a source that could influence the findings?

- What were the research methodologies? Analyze its literature review, the samples and variables used, the results, and the conclusions.

- Does the research seem to be complete? Could it have been conducted more soundly? What further questions does it raise?

- If there are conflicting studies, why do you think that is?

- How are the authors viewed in the field? Has this study been cited? If so, how has it been analyzed?

Tips:

- Review the abstracts carefully.

- Keep careful notes so that you may track your thought processes during the research process.

- Create a matrix of the studies for easy analysis, and synthesis, across all of the studies.

- << Previous: Recommended Books

- Last Updated: Jun 20, 2024 9:08 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.yale.edu/YSNDoctoral

How to Conduct a Literature Review: Types of Literature Reviews

- What is a Literature Review?

Types of Literature Reviews

- Finding "The Literature"

- Organizing/Writing

- Citation Help

Need more help? Ask a librarian!

- Online Form

- Contact a Subject Specialist

Reference hours:

- Mon-Thurs: 9 am - 11 pm

- Fri: 9 am - 4 pm

- Sat: 9 am - 4:30 pm

- Sun: 3 p.m. - 10:30 p.m.

Literature reviews are pervasive throughout various academic disciplines, and thus you can adopt various approaches to effectively organize and write your literature review. The University of Southern California created a summarized list of the various types of literature reviews, reprinted here:

- Argumentative Review

- Integrative Review Considered a form of research that reviews, critiques, and synthesizes representative literature on a topic in an integrated way such that new frameworks and perspectives on the topic are generated. The body of literature includes all studies that address related or identical hypotheses. A well-done integrative review meets the same standards as primary research in regard to clarity, rigor, and replication.

- Historical Review Few things rest in isolation from historical precedent. Historical reviews are focused on examining research throughout a period of time, often starting with the first time an issue, concept, theory, phenomena emerged in the literature, then tracing its evolution within the scholarship of a discipline. The purpose is to place research in a historical context to show familiarity with state-of-the-art developments and to identify the likely directions for future research.

- Methodological Review A review does not always focus on what someone said [content], but how they said it [method of analysis]. This approach provides a framework of understanding at different levels (i.e. those of theory, substantive fields, research approaches and data collection and analysis techniques), enables researchers to draw on a wide variety of knowledge ranging from the conceptual level to practical documents for use in fieldwork in the areas of ontological and epistemological consideration, quantitative and qualitative integration, sampling, interviewing, data collection and data analysis, and helps highlight many ethical issues which we should be aware of and consider as we go through our study.

- Systematic Review This form consists of an overview of existing evidence pertinent to a clearly formulated research question, which uses pre-specified and standardized methods to identify and critically appraise relevant research, and to collect, report, and analyse data from the studies that are included in the review. Typically it focuses on a very specific empirical question, often posed in a cause-and-effect form, such as "To what extent does A contribute to B?"

- Theoretical Review The purpose of this form is to concretely examine the corpus of theory that has accumulated in regard to an issue, concept, theory, phenomena. The theoretical literature review help establish what theories already exist, the relationships between them, to what degree the existing theories have been investigated, and to develop new hypotheses to be tested. Often this form is used to help establish a lack of appropriate theories or reveal that current theories are inadequate for explaining new or emerging research problems. The unit of analysis can focus on a theoretical concept or a whole theory or framework.

- << Previous: Starting Your Research

- Next: Finding "The Literature" >>

- Last Updated: Aug 9, 2024 11:12 AM

- URL: https://libguides.jsu.edu/literaturereview

How to Conduct a Literature Review: A Guide for Graduate Students

- Let's Get Started!

- Traditional or Narrative Reviews

- Systematic Reviews

- Typology of Reviews

- Literature Review Resources

- Developing a Search Strategy

- What Literature to Search

- Where to Search: Indexes and Databases

- Finding articles: Libkey Nomad

- Finding Dissertations and Theses

- Extending Your Searching with Citation Chains

- Forward Citation Chains - Cited Reference Searching

- Keeping up with the Literature

- Managing Your References

- Need More Information?

What is a Literature Review?

A literature review summarizes and synthesizes material on a research topic. It provides a summary of previous research and provides context for the material presented in your thesis. The literature review is your opportunity to show what you understand about your topic area, and distinguish previous research from the work you are doing. For example, your thesis may be building on an existing theory or model and extending it a new direction. It's important to provide context for your project by providing a roadmap to previous literature.

Purpose of a Literature Review

- Identifies gaps in current knowledge

- Helps you to avoid reinventing the wheel by discovering the research already conducted on a topic

- Sets the background on what has been explored on a topic so far

- Increases your breadth of knowledge in your area of research

- Helps you identify seminal works in your area

- Allows you to provide the intellectual context for your work and position your research with other, related research

- Provides you with opposing viewpoints

- Helps you to discover research methods which may be applicable to your work

- Research methods for post graduates Full cite: Greenfield (2002) Research Methods for postgraduates. 2nd Ed. London: Arnold

- A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies Full cite: Grant, M. J. and Booth, A. (2009), A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information & Libraries Journal, 26, 91–108. doi:10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

Literature Reviews: An Overview for Graduate Students

This section adapted from The Literature Review, by Charles Stuart University Library. Available: https://libguides.csu.edu.au/review.

- << Previous: Let's Get Started!

- Next: Traditional or Narrative Reviews >>

The library's collections and services are available to all ISU students, faculty, and staff and Parks Library is open to the public .

- Last Updated: Aug 12, 2024 4:07 PM

- URL: https://instr.iastate.libguides.com/gradlitrev

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

The PMC website is updating on October 15, 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- PLoS Comput Biol

- v.9(7); 2013 Jul

Ten Simple Rules for Writing a Literature Review

Marco pautasso.

1 Centre for Functional and Evolutionary Ecology (CEFE), CNRS, Montpellier, France

2 Centre for Biodiversity Synthesis and Analysis (CESAB), FRB, Aix-en-Provence, France

Literature reviews are in great demand in most scientific fields. Their need stems from the ever-increasing output of scientific publications [1] . For example, compared to 1991, in 2008 three, eight, and forty times more papers were indexed in Web of Science on malaria, obesity, and biodiversity, respectively [2] . Given such mountains of papers, scientists cannot be expected to examine in detail every single new paper relevant to their interests [3] . Thus, it is both advantageous and necessary to rely on regular summaries of the recent literature. Although recognition for scientists mainly comes from primary research, timely literature reviews can lead to new synthetic insights and are often widely read [4] . For such summaries to be useful, however, they need to be compiled in a professional way [5] .

When starting from scratch, reviewing the literature can require a titanic amount of work. That is why researchers who have spent their career working on a certain research issue are in a perfect position to review that literature. Some graduate schools are now offering courses in reviewing the literature, given that most research students start their project by producing an overview of what has already been done on their research issue [6] . However, it is likely that most scientists have not thought in detail about how to approach and carry out a literature review.

Reviewing the literature requires the ability to juggle multiple tasks, from finding and evaluating relevant material to synthesising information from various sources, from critical thinking to paraphrasing, evaluating, and citation skills [7] . In this contribution, I share ten simple rules I learned working on about 25 literature reviews as a PhD and postdoctoral student. Ideas and insights also come from discussions with coauthors and colleagues, as well as feedback from reviewers and editors.

Rule 1: Define a Topic and Audience

How to choose which topic to review? There are so many issues in contemporary science that you could spend a lifetime of attending conferences and reading the literature just pondering what to review. On the one hand, if you take several years to choose, several other people may have had the same idea in the meantime. On the other hand, only a well-considered topic is likely to lead to a brilliant literature review [8] . The topic must at least be:

- interesting to you (ideally, you should have come across a series of recent papers related to your line of work that call for a critical summary),

- an important aspect of the field (so that many readers will be interested in the review and there will be enough material to write it), and

- a well-defined issue (otherwise you could potentially include thousands of publications, which would make the review unhelpful).

Ideas for potential reviews may come from papers providing lists of key research questions to be answered [9] , but also from serendipitous moments during desultory reading and discussions. In addition to choosing your topic, you should also select a target audience. In many cases, the topic (e.g., web services in computational biology) will automatically define an audience (e.g., computational biologists), but that same topic may also be of interest to neighbouring fields (e.g., computer science, biology, etc.).

Rule 2: Search and Re-search the Literature

After having chosen your topic and audience, start by checking the literature and downloading relevant papers. Five pieces of advice here:

- keep track of the search items you use (so that your search can be replicated [10] ),

- keep a list of papers whose pdfs you cannot access immediately (so as to retrieve them later with alternative strategies),

- use a paper management system (e.g., Mendeley, Papers, Qiqqa, Sente),

- define early in the process some criteria for exclusion of irrelevant papers (these criteria can then be described in the review to help define its scope), and

- do not just look for research papers in the area you wish to review, but also seek previous reviews.

The chances are high that someone will already have published a literature review ( Figure 1 ), if not exactly on the issue you are planning to tackle, at least on a related topic. If there are already a few or several reviews of the literature on your issue, my advice is not to give up, but to carry on with your own literature review,

The bottom-right situation (many literature reviews but few research papers) is not just a theoretical situation; it applies, for example, to the study of the impacts of climate change on plant diseases, where there appear to be more literature reviews than research studies [33] .

- discussing in your review the approaches, limitations, and conclusions of past reviews,

- trying to find a new angle that has not been covered adequately in the previous reviews, and

- incorporating new material that has inevitably accumulated since their appearance.

When searching the literature for pertinent papers and reviews, the usual rules apply:

- be thorough,

- use different keywords and database sources (e.g., DBLP, Google Scholar, ISI Proceedings, JSTOR Search, Medline, Scopus, Web of Science), and

- look at who has cited past relevant papers and book chapters.

Rule 3: Take Notes While Reading

If you read the papers first, and only afterwards start writing the review, you will need a very good memory to remember who wrote what, and what your impressions and associations were while reading each single paper. My advice is, while reading, to start writing down interesting pieces of information, insights about how to organize the review, and thoughts on what to write. This way, by the time you have read the literature you selected, you will already have a rough draft of the review.