An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Family Med Prim Care

- v.4(3); Jul-Sep 2015

Validity, reliability, and generalizability in qualitative research

Lawrence leung.

1 Department of Family Medicine, Queen's University, Kingston, Ontario, Canada

2 Centre of Studies in Primary Care, Queen's University, Kingston, Ontario, Canada

In general practice, qualitative research contributes as significantly as quantitative research, in particular regarding psycho-social aspects of patient-care, health services provision, policy setting, and health administrations. In contrast to quantitative research, qualitative research as a whole has been constantly critiqued, if not disparaged, by the lack of consensus for assessing its quality and robustness. This article illustrates with five published studies how qualitative research can impact and reshape the discipline of primary care, spiraling out from clinic-based health screening to community-based disease monitoring, evaluation of out-of-hours triage services to provincial psychiatric care pathways model and finally, national legislation of core measures for children's healthcare insurance. Fundamental concepts of validity, reliability, and generalizability as applicable to qualitative research are then addressed with an update on the current views and controversies.

Nature of Qualitative Research versus Quantitative Research

The essence of qualitative research is to make sense of and recognize patterns among words in order to build up a meaningful picture without compromising its richness and dimensionality. Like quantitative research, the qualitative research aims to seek answers for questions of “how, where, when who and why” with a perspective to build a theory or refute an existing theory. Unlike quantitative research which deals primarily with numerical data and their statistical interpretations under a reductionist, logical and strictly objective paradigm, qualitative research handles nonnumerical information and their phenomenological interpretation, which inextricably tie in with human senses and subjectivity. While human emotions and perspectives from both subjects and researchers are considered undesirable biases confounding results in quantitative research, the same elements are considered essential and inevitable, if not treasurable, in qualitative research as they invariable add extra dimensions and colors to enrich the corpus of findings. However, the issue of subjectivity and contextual ramifications has fueled incessant controversies regarding yardsticks for quality and trustworthiness of qualitative research results for healthcare.

Impact of Qualitative Research upon Primary Care

In many ways, qualitative research contributes significantly, if not more so than quantitative research, to the field of primary care at various levels. Five qualitative studies are chosen to illustrate how various methodologies of qualitative research helped in advancing primary healthcare, from novel monitoring of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) via mobile-health technology,[ 1 ] informed decision for colorectal cancer screening,[ 2 ] triaging out-of-hours GP services,[ 3 ] evaluating care pathways for community psychiatry[ 4 ] and finally prioritization of healthcare initiatives for legislation purposes at national levels.[ 5 ] With the recent advances of information technology and mobile connecting device, self-monitoring and management of chronic diseases via tele-health technology may seem beneficial to both the patient and healthcare provider. Recruiting COPD patients who were given tele-health devices that monitored lung functions, Williams et al. [ 1 ] conducted phone interviews and analyzed their transcripts via a grounded theory approach, identified themes which enabled them to conclude that such mobile-health setup and application helped to engage patients with better adherence to treatment and overall improvement in mood. Such positive findings were in contrast to previous studies, which opined that elderly patients were often challenged by operating computer tablets,[ 6 ] or, conversing with the tele-health software.[ 7 ] To explore the content of recommendations for colorectal cancer screening given out by family physicians, Wackerbarth, et al. [ 2 ] conducted semi-structure interviews with subsequent content analysis and found that most physicians delivered information to enrich patient knowledge with little regard to patients’ true understanding, ideas, and preferences in the matter. These findings suggested room for improvement for family physicians to better engage their patients in recommending preventative care. Faced with various models of out-of-hours triage services for GP consultations, Egbunike et al. [ 3 ] conducted thematic analysis on semi-structured telephone interviews with patients and doctors in various urban, rural and mixed settings. They found that the efficiency of triage services remained a prime concern from both users and providers, among issues of access to doctors and unfulfilled/mismatched expectations from users, which could arouse dissatisfaction and legal implications. In UK, a care pathways model for community psychiatry had been introduced but its benefits were unclear. Khandaker et al. [ 4 ] hence conducted a qualitative study using semi-structure interviews with medical staff and other stakeholders; adopting a grounded-theory approach, major themes emerged which included improved equality of access, more focused logistics, increased work throughput and better accountability for community psychiatry provided under the care pathway model. Finally, at the US national level, Mangione-Smith et al. [ 5 ] employed a modified Delphi method to gather consensus from a panel of nominators which were recognized experts and stakeholders in their disciplines, and identified a core set of quality measures for children's healthcare under the Medicaid and Children's Health Insurance Program. These core measures were made transparent for public opinion and later passed on for full legislation, hence illustrating the impact of qualitative research upon social welfare and policy improvement.

Overall Criteria for Quality in Qualitative Research

Given the diverse genera and forms of qualitative research, there is no consensus for assessing any piece of qualitative research work. Various approaches have been suggested, the two leading schools of thoughts being the school of Dixon-Woods et al. [ 8 ] which emphasizes on methodology, and that of Lincoln et al. [ 9 ] which stresses the rigor of interpretation of results. By identifying commonalities of qualitative research, Dixon-Woods produced a checklist of questions for assessing clarity and appropriateness of the research question; the description and appropriateness for sampling, data collection and data analysis; levels of support and evidence for claims; coherence between data, interpretation and conclusions, and finally level of contribution of the paper. These criteria foster the 10 questions for the Critical Appraisal Skills Program checklist for qualitative studies.[ 10 ] However, these methodology-weighted criteria may not do justice to qualitative studies that differ in epistemological and philosophical paradigms,[ 11 , 12 ] one classic example will be positivistic versus interpretivistic.[ 13 ] Equally, without a robust methodological layout, rigorous interpretation of results advocated by Lincoln et al. [ 9 ] will not be good either. Meyrick[ 14 ] argued from a different angle and proposed fulfillment of the dual core criteria of “transparency” and “systematicity” for good quality qualitative research. In brief, every step of the research logistics (from theory formation, design of study, sampling, data acquisition and analysis to results and conclusions) has to be validated if it is transparent or systematic enough. In this manner, both the research process and results can be assured of high rigor and robustness.[ 14 ] Finally, Kitto et al. [ 15 ] epitomized six criteria for assessing overall quality of qualitative research: (i) Clarification and justification, (ii) procedural rigor, (iii) sample representativeness, (iv) interpretative rigor, (v) reflexive and evaluative rigor and (vi) transferability/generalizability, which also double as evaluative landmarks for manuscript review to the Medical Journal of Australia. Same for quantitative research, quality for qualitative research can be assessed in terms of validity, reliability, and generalizability.

Validity in qualitative research means “appropriateness” of the tools, processes, and data. Whether the research question is valid for the desired outcome, the choice of methodology is appropriate for answering the research question, the design is valid for the methodology, the sampling and data analysis is appropriate, and finally the results and conclusions are valid for the sample and context. In assessing validity of qualitative research, the challenge can start from the ontology and epistemology of the issue being studied, e.g. the concept of “individual” is seen differently between humanistic and positive psychologists due to differing philosophical perspectives:[ 16 ] Where humanistic psychologists believe “individual” is a product of existential awareness and social interaction, positive psychologists think the “individual” exists side-by-side with formation of any human being. Set off in different pathways, qualitative research regarding the individual's wellbeing will be concluded with varying validity. Choice of methodology must enable detection of findings/phenomena in the appropriate context for it to be valid, with due regard to culturally and contextually variable. For sampling, procedures and methods must be appropriate for the research paradigm and be distinctive between systematic,[ 17 ] purposeful[ 18 ] or theoretical (adaptive) sampling[ 19 , 20 ] where the systematic sampling has no a priori theory, purposeful sampling often has a certain aim or framework and theoretical sampling is molded by the ongoing process of data collection and theory in evolution. For data extraction and analysis, several methods were adopted to enhance validity, including 1 st tier triangulation (of researchers) and 2 nd tier triangulation (of resources and theories),[ 17 , 21 ] well-documented audit trail of materials and processes,[ 22 , 23 , 24 ] multidimensional analysis as concept- or case-orientated[ 25 , 26 ] and respondent verification.[ 21 , 27 ]

Reliability

In quantitative research, reliability refers to exact replicability of the processes and the results. In qualitative research with diverse paradigms, such definition of reliability is challenging and epistemologically counter-intuitive. Hence, the essence of reliability for qualitative research lies with consistency.[ 24 , 28 ] A margin of variability for results is tolerated in qualitative research provided the methodology and epistemological logistics consistently yield data that are ontologically similar but may differ in richness and ambience within similar dimensions. Silverman[ 29 ] proposed five approaches in enhancing the reliability of process and results: Refutational analysis, constant data comparison, comprehensive data use, inclusive of the deviant case and use of tables. As data were extracted from the original sources, researchers must verify their accuracy in terms of form and context with constant comparison,[ 27 ] either alone or with peers (a form of triangulation).[ 30 ] The scope and analysis of data included should be as comprehensive and inclusive with reference to quantitative aspects if possible.[ 30 ] Adopting the Popperian dictum of falsifiability as essence of truth and science, attempted to refute the qualitative data and analytes should be performed to assess reliability.[ 31 ]

Generalizability

Most qualitative research studies, if not all, are meant to study a specific issue or phenomenon in a certain population or ethnic group, of a focused locality in a particular context, hence generalizability of qualitative research findings is usually not an expected attribute. However, with rising trend of knowledge synthesis from qualitative research via meta-synthesis, meta-narrative or meta-ethnography, evaluation of generalizability becomes pertinent. A pragmatic approach to assessing generalizability for qualitative studies is to adopt same criteria for validity: That is, use of systematic sampling, triangulation and constant comparison, proper audit and documentation, and multi-dimensional theory.[ 17 ] However, some researchers espouse the approach of analytical generalization[ 32 ] where one judges the extent to which the findings in one study can be generalized to another under similar theoretical, and the proximal similarity model, where generalizability of one study to another is judged by similarities between the time, place, people and other social contexts.[ 33 ] Thus said, Zimmer[ 34 ] questioned the suitability of meta-synthesis in view of the basic tenets of grounded theory,[ 35 ] phenomenology[ 36 ] and ethnography.[ 37 ] He concluded that any valid meta-synthesis must retain the other two goals of theory development and higher-level abstraction while in search of generalizability, and must be executed as a third level interpretation using Gadamer's concepts of the hermeneutic circle,[ 38 , 39 ] dialogic process[ 38 ] and fusion of horizons.[ 39 ] Finally, Toye et al. [ 40 ] reported the practicality of using “conceptual clarity” and “interpretative rigor” as intuitive criteria for assessing quality in meta-ethnography, which somehow echoed Rolfe's controversial aesthetic theory of research reports.[ 41 ]

Food for Thought

Despite various measures to enhance or ensure quality of qualitative studies, some researchers opined from a purist ontological and epistemological angle that qualitative research is not a unified, but ipso facto diverse field,[ 8 ] hence any attempt to synthesize or appraise different studies under one system is impossible and conceptually wrong. Barbour argued from a philosophical angle that these special measures or “technical fixes” (like purposive sampling, multiple-coding, triangulation, and respondent validation) can never confer the rigor as conceived.[ 11 ] In extremis, Rolfe et al. opined from the field of nursing research, that any set of formal criteria used to judge the quality of qualitative research are futile and without validity, and suggested that any qualitative report should be judged by the form it is written (aesthetic) and not by the contents (epistemic).[ 41 ] Rolfe's novel view is rebutted by Porter,[ 42 ] who argued via logical premises that two of Rolfe's fundamental statements were flawed: (i) “The content of research report is determined by their forms” may not be a fact, and (ii) that research appraisal being “subject to individual judgment based on insight and experience” will mean those without sufficient experience of performing research will be unable to judge adequately – hence an elitist's principle. From a realism standpoint, Porter then proposes multiple and open approaches for validity in qualitative research that incorporate parallel perspectives[ 43 , 44 ] and diversification of meanings.[ 44 ] Any work of qualitative research, when read by the readers, is always a two-way interactive process, such that validity and quality has to be judged by the receiving end too and not by the researcher end alone.

In summary, the three gold criteria of validity, reliability and generalizability apply in principle to assess quality for both quantitative and qualitative research, what differs will be the nature and type of processes that ontologically and epistemologically distinguish between the two.

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

Articles and blog posts

Validity and reliability in qualitative research.

What is Validity and Reliability in Qualitative research?

In Quantitative research, reliability refers to consistency of certain measurements, and validity – to whether these measurements “measure what they are supposed to measure”. Things are slightly different, however, in Qualitative research.

Reliability in qualitative studies is mostly a matter of “being thorough, careful and honest in carrying out the research” (Robson, 2002: 176). In qualitative interviews, this issue relates to a number of practical aspects of the process of interviewing, including the wording of interview questions, establishing rapport with the interviewees and considering ‘power relationship’ between the interviewer and the participant (e.g. Breakwell, 2000; Cohen et al., 2007; Silverman, 1993).

What seems more relevant when discussing qualitative studies is their validity , which very often is being addressed with regard to three common threats to validity in qualitative studies, namely researcher bias , reactivity and respondent bias (Lincoln and Guba, 1985).

Researcher bias refers to any kind of negative influence of the researcher’s knowledge, or assumptions, of the study, including the influence of his or her assumptions of the design, analysis or, even, sampling strategy. Reactivity , in turn, refers to a possible influence of the researcher himself/herself on the studied situation and people. Respondent bias refers to a situation where respondents do not provide honest responses for any reason, which may include them perceiving a given topic as a threat, or them being willing to ‘please’ the researcher with responses they believe are desirable.

Robson (2002) suggested a number of strategies aimed at addressing these threats to validity, being prolonged involvement , triangulation , peer debriefing , member checking , negative case analysis and keeping an audit trail .

So, what exactly are these strategies and how can you apply them in your research?

Prolonged involvement refers to the length of time of the researcher’s involvement in the study, including involvement with the environment and the studied participants. It may be granted, for example, by the duration of the study, or by the researcher belonging to the studied community (e.g. a student investigating other students’ experiences). Being a member of this community, or even being a friend to your participants (see my blog post on the ethics of researching friends ), may be a great advantage and a factor that both increases the level of trust between you, the researcher, and the participants and the possible threats of reactivity and respondent bias. It may, however, pose a threat in the form of researcher bias that stems from your, and the participants’, possible assumptions of similarity and presuppositions about some shared experiences (thus, for example, they will not say something in the interview because they will assume that both of you know it anyway – this way, you may miss some valuable data for your study).

Triangulation may refer to triangulation of data through utilising different instruments of data collection, methodological triangulation through employing mixed methods approach and theory triangulation through comparing different theories and perspectives with your own developing “theory” or through drawing from a number of different fields of study.

Peer debriefing and support is really an element of your student experience at the university throughout the process of the study. Various opportunities to present and discuss your research at its different stages, either at internally organised events at your university (e.g. student presentations, workshops, etc.) or at external conferences (which I strongly suggest that you start attending) will provide you with valuable feedback, criticism and suggestions for improvement. These events are invaluable in helping you to asses the study from a more objective, and critical, perspective and to recognise and address its limitations. This input, thus, from other people helps to reduce the researcher bias.

Member checking , or testing the emerging findings with the research participants, in order to increase the validity of the findings, may take various forms in your study. It may involve, for example, regular contact with the participants throughout the period of the data collection and analysis and verifying certain interpretations and themes resulting from the analysis of the data (Curtin and Fossey, 2007). As a way of controlling the influence of your knowledge and assumptions on the emerging interpretations, if you are not clear about something a participant had said, or written, you may send him/her a request to verify either what he/she meant or the interpretation you made based on that. Secondly, it is common to have a follow-up, “validation interview” that is, in itself, a tool for validating your findings and verifying whether they could be applied to individual participants (Buchbinder, 2011), in order to determine outlying, or negative, cases and to re-evaluate your understanding of a given concept (see further below). Finally, member checking, in its most commonly adopted form, may be carried out by sending the interview transcripts to the participants and asking them to read them and provide any necessary comments or corrections (Carlson, 2010).

Negative case analysis is a process of analysing ‘cases’, or sets of data collected from a single participant, that do not match the patterns emerging from the rest of the data. Whenever an emerging explanation of a given phenomenon you are investigating does nto seem applicable to one, or a small number, of the participants, you should try to carry out a new line of analysis aimed at understanding the source of this discrepancy. Although you may be tempted to ignore these “cases” in fear of having to do extra work, it should become your habit to explore them in detail, as the strategy of negative case analysis, especially when combined with member checking, is a valuable way of reducing researcher bias.

Finally, the notion of keeping an audit trail refers to monitoring and keeping a record of all the research-related activities and data, including the raw interview and journal data, the audio-recordings, the researcher’s diary (see this post about recommended software for researcher’s diary ) and the coding book.

If you adopt the above strategies skilfully, you are likely to minimize threats to validity of your study. Don’t forget to look at the resources in the reference list, if you would like to read more on this topic!

Breakwell, G. M. (2000). Interviewing. In Breakwell, G.M., Hammond, S. & Fife-Shaw, C. (eds.) Research Methods in Psychology. 2nd Ed. London: Sage. Buchbinder, E. (2011). Beyond Checking: Experiences of the Validation Interview. Qualitative Social Work, 10 (1), 106-122. Carlson, J.A. (2010). Avoiding Traps in Member Checking. The Qualitative Report, 15 (5), 1102-1113. Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2007). Research Methods in Education. 6th Ed. London: Routledge. Curtin, M., & Fossey, E. (2007). Appraising the trustworthiness of qualitative studies: Guidelines for occupational therapists. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 54, 88-94. Lincoln, Y. S. & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic Inquiry. Newbury Park, CA: SAGE. Robson, C. (2002). Real world research: a resource for social scientists and practitioner-researchers. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishers.

Silverman, D. (1993) Interpreting Qualitative Data. London: Sage.

There is an argument for using your identity and biases to enrich the research (see my recent blog… researcheridentity.wordpress.com) providing that the researcher seeks to fully comprehend their place in the research and is fully open, honest and clear about that in the write up. I have come to see reliability and validity more as a defence of is the research rigorous, thorough and careful therefore is it morally, ethically and accurately defensible?

Hi Nathan, thank you for your comment. I agree that being explicit about your own status and everything that you bring into the study is important – it’s a very similar issue (although seemingly it’s a different topic) to what I discussed in the blog post about grounded theory where I talked about being explicit about the influence of our previous knowledge on the data. I have also experienced this dilemma of “what to do with” my status as simultaneously a “researcher” an “insider” a “friend” and a “fellow Polish migrant” when conducting my PhD study of Polish migrants’ English Language Identity, and came to similar conclusions as the ones you reach in your article – to acknowledge these “multiple identities” and make the best of them.

I have read your blog article and really liked it – would you mind if I shared it on my Facebook page, and linked to it from my blog section on this page?

Please do share my blog by all means; I’d be delighted. Are you on twitter? I’m @Nathan_AHT_EDD I strongly believe that we cannot escape our past, including our multiple/present habitus and identities when it comes to qualitative educational research. It is therefore, arguably, logical to ethically and sensibly embrace it/them to enrich the data. Identities cannot be taken on and off like a coat, they are, “lived as deeply committed personal projects” (Clegg, 2008: p.336) and so if we embrace them we bring a unique insight into the process and have a genuine investment to make the research meaningful and worthy of notice.

Hi Nathan, I don’t have twitter… I know – somehow I still haven’t had time to get to grips with it. I do have Facebook, feel free to find me there. I also started to follow your blog so that I am notified about your content. I agree with what you said here and in your posts, and I like the topic of your blog. This is definitely something that we should pay more attention to when doing research. It would be interesting to talk some time and exchange opinions, as our research interests seem very closely related. Have a good day !

To read this content please select one of the options below:

Please note you do not have access to teaching notes, comprehensive criteria to judge validity and reliability of qualitative research within the realism paradigm.

Qualitative Market Research

ISSN : 1352-2752

Article publication date: 1 September 2000

Aims to address a gap in the literature about quality criteria for validity and reliability in qualitative research within the realism scientific paradigm. Six comprehensive and explicit criteria for judging realism research are developed, drawing on the three elements of a scientific paradigm of ontology, epistemology and methodology. The first two criteria concern ontology, that is, ontological appropriateness and contingent validity. The third criterion concerns epistemology: multiple perceptions of participants and of peer researchers. The final three criteria concern methodology: methodological trustworthiness, analytic generalisation and construct validity. Comparisons are made with criteria in other paradigms, particularly positivism and constructivism. An example of the use of the criteria is given. In conclusion, this paper’s set of six criteria will facilitate the further adoption of the realism paradigm and its evaluation in marketing research about, for instance, networks and relationship marketing.

- Marketing research

- Qualitative techniques

- Methodology

- Case studies

Healy, M. and Perry, C. (2000), "Comprehensive criteria to judge validity and reliability of qualitative research within the realism paradigm", Qualitative Market Research , Vol. 3 No. 3, pp. 118-126. https://doi.org/10.1108/13522750010333861

Copyright © 2000, MCB UP Limited

Related articles

We’re listening — tell us what you think, something didn’t work….

Report bugs here

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Join us on our journey

Platform update page.

Visit emeraldpublishing.com/platformupdate to discover the latest news and updates

Questions & More Information

Answers to the most commonly asked questions here

Validity, Reliability, and Fairness Evidence for the JD-Next Exam FYA LSAT GRE

At a time when institutions of higher education are exploring alternatives to traditional admissions testing, institutions are also seeking to better support students and prepare them for academic success. Under such an engaged model, one may seek to measure not just the accumulated knowledge and skills that students would bring to a new academic program but also their ability to grow and learn through the academic program. To help prepare students for law school before they matriculate, the JD-Next is a fully online, noncredit, 7- to 10-week course to train potential juris doctor students in case reading and analysis skills. This study builds on the work presented for previous JD-Next cohorts by introducing new scoring and reliability estimation methodologies based on a recent redesign of the assessment for the 2021 cohort, and it presents updated validity and fairness findings using first-year grades, rather than merely first-semester grades as in prior cohorts. Results support the claim that the JD-Next exam is reliable and valid for predicting law school success, providing a statistically significant increase in predictive power over baseline models, including entrance exam scores and grade point averages. In terms of fairness across racial and ethnic groups, smaller score disparities are found with JD-Next than with traditional admissions assessments, and the assessment is shown to be equally predictive for students from underrepresented minority groups and for first-generation students. These findings, in conjunction with those from previous research, support the use of the JD-Next exam for both preparing and admitting future law school students.

- Request Copy (specify title and report number, if any)

- https://doi.org/10.1002/ets2.12378

- Open access

- Published: 31 May 2024

A scale for measuring nursing digital application skills: a development and psychometric testing study

- Shijia Qin 1 ,

- Jianzhong Zhang 1 ,

- Xiaomin Sun 2 ,

- Ge Meng 1 ,

- Xinqi Zhuang 1 ,

- Yitong Jia 1 ,

- Wen-Xin Shi 1 &

- Yin-Ping Zhang 1

BMC Nursing volume 23 , Article number: 366 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

226 Accesses

Metrics details

The adoption of digitization has emerged as a new trend in the advancement of healthcare systems. To ensure high-quality care, nurses should possess sufficient skills to assist in the digital transformation of healthcare practices. Suitable tools have seldom been developed to assess nurses’ skills in digital applications. This study aimed to develop the Nursing Digital Application Skill Scale (NDASS) and test its psychometric properties.

The Nursing Digital Application Skill Scale was developed in three phases. In Phase 1, an item pool was developed based on previous literature and the actual situation of nursing work. Phase 2 included 14 experts’ assessment of content validity and a focus group interview with 30 nurses to pretest the scale. In phase 3, 429 registered nurses were selected from March to June 2023, and item analysis, exploratory factor analysis, and confirmatory factor analysis were used to refine the number of items and explore the factor structure of the scale. Additionally, reliability was determined by internal consistency and test-retest reliability.

The final version of the NDASS consisted of 12 items. The content validity index of NDASS reached 0.975 at an acceptable level. The convergent validity test showed that the average variance extracted value was 0.694 (> 0.5) and the composite reliability value was 0.964 (> 0.7), both of which met the requirements. The principal component analysis resulted in a single-factor structure explaining 74.794% of the total variance. All the fitting indices satisfied the standard based upon confirmatory factor analyses, indicating that the single-factor structure contributed to an ideal model fit. The internal consistency appeared high for the NDASS, reaching a Cronbach’s alpha value of 0.968. The test-retest reliability was 0.740, and the split-half coefficient was 0.935.

The final version of the NDASS, which possesses adequate psychometric properties, is a reliable and effective instrument for nurses to self-assess digital skills in nursing work and for nursing managers in designing nursing digital skill training.

Peer Review reports

With the rapid development of digital technologies, we have ushered in the era of digitalization. As a global phenomenon, digitization involves the integration of digital technology into increasingly diverse aspects of professional and personal lives [ 1 ]. In healthcare, numerous digital innovations, such as open access to health and treatment information, biomedical research on the Internet, the provision of mobile health services, wearable devices, health information technology, telehealth and telemedicine, have been implemented [ 2 ]. These innovations are envisioned to make healthcare more accessible and flexible for the general public, eliminating inequality and inefficiencies in the healthcare system while also enhancing the quality and satisfaction of patient care [ 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 ]. More importantly, health interventions delivered through digital technologies have proven beneficial in clinical practice, especially in the fields of disease rehabilitation, vaccination, and improvement of psychological problems [ 7 , 8 , 9 ]. According to the 14th Five-Year Plan for National Health Informatization issued by the National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China, digital health services will become an important part of the medical and health service system. It can be seen that digitization has become a new trend in the future development of health systems.

As the cornerstone of the healthcare system, nurses play an indispensable role in providing professional, high-quality, and safe patient care [ 10 ]. Previous investigations of the inclusion of digitalization in patient care have focused on the effects and challenges of digital technology applications [ 11 , 12 ], the economic benefits of digital technologies [ 13 ], and the opinions and insights of nurses on digital technology applications [ 14 ]. However, another issue that has not been given enough focus is the importance of nurses having sufficient skills to integrate new technologies into clinical practice and use digital technologies effectively in daily work. Nurses with inadequate skills will not be able to use digital technologies appropriately, resulting in an increased incidence of errors and the creation of new safety risks [ 15 ]. Negative experiences of technology usage can also influence nurses’ attitudes toward other new technologies [ 16 ]. In addition, lower skill levels were reportedly associated with greater technostress, which has a nonnegligible impact on long-term consequences, such as burnout symptoms, job satisfaction, and headaches [ 17 ]. Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the importance of telehealth, which places greater demands on nurses’ digital skills.

Currently, there is no clear definition of digitalization skills possessed by nurses. In its publication Key Competences for Lifelong Learning , the European Council defined digital competence as the confident, critical and responsible use of, and engagement with, digital technologies for learning, at work, and for participation in society. An individual who is considered competent in a particular field should possess knowledge, skills, and attitude simultaneously [ 18 ]. This study aims to assess the proficiency of nurses in utilizing digital technologies effectively within clinical settings, particularly focusing on their skill mastery in this domain. Therefore, we are more inclined to use “digital skill” instead of “digital competence” to define it. The digital literacy framework for teachers developed by the Ministry of Education of China suggests that digital application refers to the skill of teachers to apply digital technology resources to carry out educational and teaching activities. Referring to the definitions of the Council and the Ministry of Education, this study further defines these skills as nurses’ skills in utilizing digital technologies to carry out nursing work and names these skills “nursing digital application skills”.

Researchers have developed numerous digital skill assessment tools for different populations, including college students, schoolchildren, working professionals, and others [ 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 ]. These evaluation standards focused on the characteristics of the respective populations and failed to address the professional content of health care. A few instruments for measuring healthcare professionals’ core competencies have incorporated individual items related to the use of digital technologies; however, these instruments cannot provide a comprehensive assessment of digital skills [ 23 , 24 ]. One study used five items to measure and broadly generalize the digital abilities of health professionals in psychiatric hospitals, but the questions were vague [ 17 ]. Other studies have evaluated skills using certain digital technologies, such as electronic health records (EHR) documentation and robots [ 25 , 26 ]. In addition, the digital health scale developed by Jarva et al. intersects with the elements of nurses’ digital application skills [ 27 ]. In this context, this study aimed to develop a reliable and brief scale, namely, the Nursing Digital Application Skill Scale (NDASS), to rapidly evaluate the digital skills required in nursing work.

Research design and methods

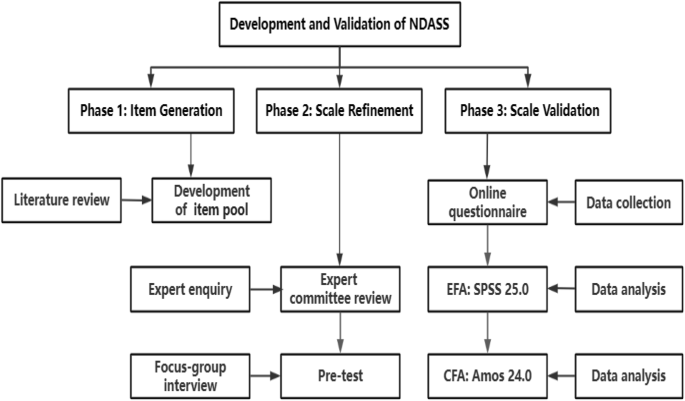

A multistep approach, which included item generation, scale refinement and scale validation, was utilized in this methodological research. In phase 1, the initial item pool was developed based on an extensive literature review. In phase 2, an expert committee review was conducted to evaluate the importance of the items. A pretest was then conducted among a small sample of 30 nurses. The participants completed the scale and provided feedback on the scale’s applicability and acceptance level through a focus group interview. In phase 3, an online questionnaire was used to gather information from participants at several hospitals in Northwest China. After the data were collected, exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted with SPSS 25.0 to determine the internal factor structure of the scale, and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed with AMOS 24.0 to verify the model-data fit and convergent validity. Figure 1 displays the three phases and different methods used in each phase.

Phases and methods of development and validation of the NDASS

Item generation

The initial item pool was developed by a research team of five researchers, including a nursing professor, two nursing doctoral students and two nursing students with master’s degree. Through an extensive literature review, the team integrated items related to the application of digital technologies from previous instruments and then removed or merged items with similar meanings. The key terms were (skill OR literacy OR competenc*) AND (“digital technology” OR “digital health” OR “Information Computer Technology” OR informatics OR computer OR internet OR media) AND (nurs* OR “health professional” OR “health care”) AND (scale OR questionnaire OR measure* OR assess* OR evaluat*). The databases Web of Science, PubMed, Medline, China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) and Wan Fang Data were searched from their inception through September 2022. Only articles in Chinese and English were included.

To accommodate nursing work scenarios, items were rewritten according to the criteria for “nurses’ skills in utilizing digital technologies to carry out nursing work.” On this basis, the expression of the items was unified, and the order of the items was changed to facilitate the reading of participants. The first version of the NDASS was developed with the reference of the Digital Competence Framework for Citizens 2.2 published by the European Commission, based on the questionnaires of Fan et al. [ 21 ], van Laar et al. [ 22 ], Peart et al. [ 28 ], a digital literacy framework for teachers, and so on. As the scale was specifically developed for nurses, we added some items that assess specific digital skills required in the context of clinical nursing according to the evaluation instruments for nurses’ related skills. For example, Item 6, “I can use statistical software to analyze nursing data”, was derived from the Information Literacy Self-rating Scale for Clinical Nurses [ 29 ]. The scale was designed with a 5-point Likert scale, with 5 response options available for the items, ranging from 1 for strongly disagree to 5 for strongly agree. The 14 items of the first version of the NDASS are shown in Table 1 .

Scale refinement

At this stage, the scale was refined through an expert committee review and a pilot study. The preliminary version of the NDASS was reviewed by a panel of 14 independent experts who specialized in nursing management, nursing education, clinical nursing and scale development research. All the experts held deputy senior titles or higher and had an average of more than 25 years of work experience. The experts were invited to judge the importance of each item for content validation using a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (not important) to 5 (very important). Items rated as 4 or 5 suggest that experts have reached a consensus regarding importance. In addition, the experts were also asked to provide specific suggestions for improvements to the scale and each item.

Before applying the reviewed scale to a large sample, we ran a pilot study among a small sample of 30 nurses in Northwest China. These volunteers were recruited through convenience sampling and were asked to complete the scales. The pilot study allowed us to detect problems with wording, terminology, instructions and the clarity of options. A focus group interview was also conducted to explore participants’ perceptions and understanding of the scale and items and to take their advice for improvement. The outline of the interview was as follows: Q1: Do you have any suggestions for the instructions of the scale? Q2: Which items do you find difficult to comprehend? Q3: Do you have any recommendations for the wording of the items? After this process, the official version was developed.

Participant and setting

A cross-sectional validation study was conducted with 429 registered nurses from various hospitals in Northwest China using convenience sampling. The inclusion criteria for participants were as follows: (a) currently employed in a medical unit; and (b) willing to participate in the study. Participants who took extended leave were excluded. Anonymity and confidentiality were assured, and participants were told that they could withdraw at any point without consequences. From March to June 2023, the data were collected via an online survey utilizing sojump (an online research survey tool; http://www.sojump.com ). Approval was obtained from the Ethics Committees of the First Affiliated Hospital of Xi’an Jiaotong University. All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki. Five nurses refused to complete the survey. Thus, we obtained 424 cases for analysis. The 424 cases were randomly split into two groups using SPSS 25.0: one group of 200 cases for EFA and another group of 224 cases for CFA.

Data analysis

SPSS 25.0 and AMOS 24.0 were used for the data analysis. The statistical description of the demographic variables was carried out by frequency tables, means, and standard deviations (SDs). The content validity index (CVI) was computed to quantify scores for each item and the whole scale. Items rated as 3 (moderately important), 4 (important), or 5 (very important) suggest that experts have reached a consensus regarding importance. The content validity indices of each item (I-CVI) and the overall scale (S-CVI) were calculated, and an S-CVI of more than 0.90 and an I-CVI of more than 0.78 were considered valid [ 30 ]. The validity of each item was determined through item analysis. We considered unfavorable floor or ceiling effects to be present if more than 15% of the individuals reached the highest or lowest score.

EFA was conducted using principal component analysis (PCA) as the extraction method and the varimax method as the rotation method to determine the factor structure of the questionnaire [ 31 ]. Items were deemed relevant if factor-loading coefficients exceeded 0.40 and extracted factors achieved an eigenvalue ≥ 1.0 [ 32 ]. A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was also performed to verify the results. The expected values of the indices recommended were as follows [ 33 ]: (a) chi-square divided by the degrees of freedom ≤ 3; (b) the root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA) < 0.08; and (c) the comparative fit index (CFI), normed fit index (NFI), goodness-of-fit index (GFI) and Incremental Fit Index (IFI) > 0.90. It should be noted that the above model fit threshold values are simple guidelines and should not be interpreted as strict rules [ 21 ]. In addition, we calculated the composite reliability (CR) and average variance extracted (AVE) values for the factors to assess their convergent validity [ 34 ].

The internal consistency was calculated with the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient. A Cronbach’s alpha value of 0.7 or greater was considered satisfactory [ 35 ]. The split-half coefficient reliability was assessed by using half of the odd and even items. Test-retest reliability was assessed by using the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) [ 36 ]. ICC values of 0.60 to 0.80 were considered to indicate good reliability, and ICC values above 0.80 were considered to indicate excellent reliability [ 37 ].

Refinement of NDASS

The expert review resulted in the rewording of 3 items and the deletion of 1 item, which was considered to be of low importance, leaving a total of 13 items. The S-CVI of the scale reached 0.975, which indicated excellent content validity. The I-CVIs were above 0.78 except for item 12 (“I can tolerate different perspectives on the internet”) (see Table 2 ). This item was deleted because of its low validity. In addition, the experts suggested modifying items with complex expressions and repetitive content. For example, the meaning of “reproduce” in item 1 belonged to item 2. Therefore, we removed the word “reproduce” in item 1. According to the experts, the description of item 4 was somewhat cumbersome, and we modified it to “I can use digital nursing equipment proficiently”. Similarly, the term “objectively” in item 5 was removed. The adjusted version of the NDASS was used for subsequent pilot study.

The 30 nurses who participated in the pretesting were mainly from the ICU (64.6%), internal medicine (18.5%), surgery (9.2%), and other departments (7.7%). Some participants stated that the explanation of “digital skill” in the instructions was not simple enough, and the meaning of “digital” could not be understood clearly by reading the definition. After further explanation of the “digital”, the participants expressed their understanding and approval of the scale and items. We recorded participants’ suggestions during the pilot study and made modifications after discussion.

Sample characteristics

The demographic data of the individuals included in the validation study are presented in Table 3 . A total of 424 nurses who worked in the departments of internal medical (29.2%), surgery (14.6%), obstetrics and gynecology (4.0%), pediatrics (6.1%), emergency (6.4%), intensive care unit (14.4%), operating room (5.2%), rehabilitation unit (1.0%), or other (19.1%) units were included. The mean age was 32.11 years (SD = 5.48), and the mean years of service was 9.61 (SD = 6.05). Participants included 403 (95.0%) females and 21 (5.0%) males, the vast majority of whom obtained a bachelor’s degree or above (93.9%). Participants spent an average of 6.34 hours per day (SD = 4.30) using digital services, while only 27.1% had experience in digital courses or training. The average score of the NDASS (12 items) was 44.77 (SD = 9.49). There were significant differences in hospital level ( t = 8.073, p < 0.001), type of unit ( F = 7.312, p < 0.001), professional title ( F = 3.175, p < 0.05), and received digital courses or training ( t = 2.924, p < 0.01).

Item analysis

The values of the skewness and kurtosis of each item were examined, which ranged from − 0.84 to -0.14 and from − 0.35 to 1.58, respectively. The top 27% of the highest-scoring participants comprised the high group, and the lower 27% of the lowest-scoring participants comprised the low group. The mean score of each item in the two groups was subsequently compared using an independent samples t test to test the difference between the two groups, and the critical ratio (CR) of the item was obtained. The results showed that there was a statistically significant difference in the scores for each item between the high group and the low group ( p < 0.001), and the CR value for each item was greater than 3, indicating that every item had good discrimination without the floor or ceiling effect. No items were deleted at this stage.

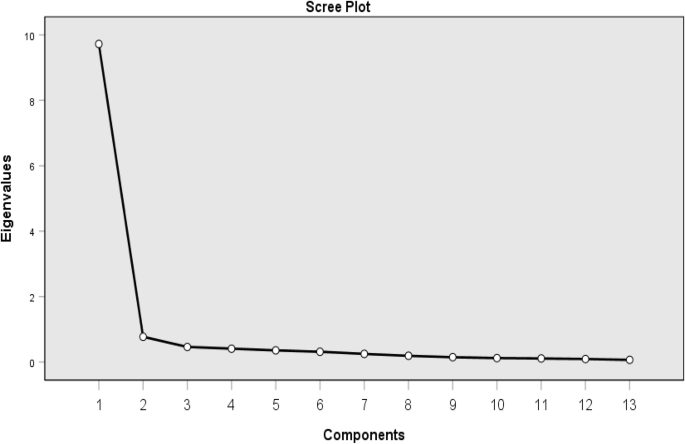

Exploratory factor analysis

The correlation matrix showed ample adequacy of the sample size (the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure was 0.954, and the Bartlett test results (χ 2 = 3156.793, p < 0.001) rejected the hypothesis of zero correlations. The scree plot (see Fig. 2 ) indicated that there was one factor. In addition, based on Kaiser’s criterion of extracting factors with eigenvalues greater than 1, a one-factor structure (Eigenvalue = 9.723) that explained 74.794% of the variance in the data were identified by the pattern matrix (see Table 4 ). Exploratory factor analysis of the 13 items produced factor loadings ranging from 0.786 to 0.918 (> 0.4).

Scree plot of the NDASS (13 items)

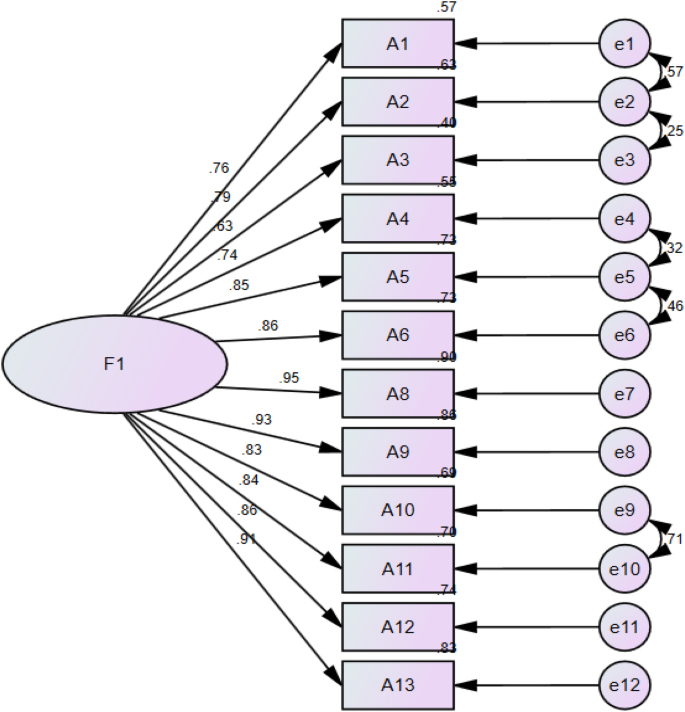

Confirmatory factor analysis

A single-factor model was established according to the results of exploratory factor analysis (see Fig. 3 ). Model fit indices of each factor of the third version of the NDASS (13 items) were calculated. The CFA results revealed the following model fit indices: χ 2 /df = 7.602 (> 3), p < 0.001, RMSEA = 0.172 (> 0.08), CFI = 0.869 (< 0.9), NFI = 0.853 (< 0.9), and GFI = 0.741 (< 0.9). The results showed that the model and the data did not fit well (Table 5 ). During the model correction process, according to the modification index (M.I.) provided by AMOS 24.0, we found that item 7 had a greater residual correlation with item 8 (M.I. = 15.151) and had a lower factor loading than item 8. It is difficult to explain the negative correlation between item 7 and item 8 from a professional perspective. Additionally, upon careful examination of item 7 (I can express my thoughts clearly on the Internet), it became apparent that this item was more focused on measuring Internet skills. As a relatively basic skill, Internet skills reflect the limited level of digital application skills available to nurses. Thus, item 7 was removed from this model. In the modified model, the fit indices were excellent: the RMSEA was 0.076, less than 0.08; the GFI was 0.921; the CFI and IFI were both 0.979; and the NFI was 0.964, exceeding the benchmark of 0.90. Eventually, the single-factor model suitably fitted the survey data, and its application was testified to be appropriate for the population surveyed.

The schematic diagram of final standardized model fitting of the NDASS

To further confirm the validity of the fourth version of the NDASS (12 items), we checked the convergent validity. Convergent validity, also known as aggregate validity, might be tested by calculating the average variance extracted (AVE) and construct reliability (CR) values. The AVE value of this model was 0.694 (> 0.5), and the CR value was 0.964 (> 0.7). Both the AVE and CR values provided evidence of the convergent validity of the fourth version of the NDASS (12 items).

Reliability

The Cronbach’s alpha of the final version of the NDASS was 0.968. The split-half reliability for the overall questionnaire was 0.935. The test-retest reliability according to the ICC was 0.740 ( p < 0.001). The results indicated that the Nursing Digital Application Skill Scale has good reliability. The final version of the NDASS is shown in Table 6 .

With the integration of digital technologies in healthcare, scholars are considering the prerequisites for engagement with digital technologies and the importance of digital skills for effective engagement. In the current contribution, we proposed a new instrument for measuring nursing digital application skills through three steps: item generation, scale refinement, and scale validation. This five-point Likert scale with a single dimension is widely applicable. Its short length and concise presentation can help nurses make quick assessments. The results of the reliability and validity analysis showed that the 12-item NDASS was a reliable and valid instrument.

The tool was developed around the concept of nursing digital application skills and with reference to other digital skill assessment tools. For example, Fan [ 21 ] developed a digital skills questionnaire for Chinese college students, with a portion of the content being “use of digital means”, which is consistent with the theme of this study. However, because the respondents of the questionnaire were students, these items were related to learning. To this end, we established a research group composed of nursing education experts, clinical nurses, and doctoral and master’s students in nursing. The items were adapted based on the judgment of nursing knowledge to suit working professionals. A similar situation arose in the adaptation of the tools of Vanlaar [ 22 ]. Although the digital technology used in nursing was described, there was still a lack of nursing features in these items. An initial item pool for the NDASS was established by reviewing relevant literature and exploring the digital needs of the nursing profession. To refine the items, experts and clinical nurses were invited to evaluate the setting, description, and scoring rules of the items. Nursing authorities from universities and hospitals across different provinces in China ensured that the scale was refined under the guidance of professionalism and experience. The clinical nurses who participated in the pretest were also representatives from different hospitals and departments. The focus group interview confirmed that hospitals at different levels have varying degrees of digitalization, and clinical nurses’ involvement in digital technology also varies. Therefore, nurses from different hospitals were included to jointly complete the scale validation.

The success of an instrument largely depends on both the reliability and the validity of the measurement. The results of the expert review showed that the content validity index of most items was high, and the scale-level CVI reached 0.975, which met the recommended criteria [ 38 ]. The CVI of item 12 (“I can tolerate different perspectives on the internet”) was at a critical value. Based on expert opinions, the team believes that accommodating all perspectives is not a necessary criterion for digital skills. Instead, it is more crucial to utilize desirable recommendations, which are reflected in the other three items (“promote nurse-patient relationships”, “collaborate with others”, and “participate in social activities”). These three items are sufficient for describing nurses’ ability to communicate and socialize with different groups of people by using digital technologies. Therefore, item 12 was discarded.

Exploratory factor analysis indicated that only one principal component was extracted, accounting for 74.794% of the total variance. This result was consistent with that of a study that assessed the digital competence of health professionals in Swiss psychiatric hospitals [ 17 ]. This may also be related to the fact that the initial item pool was built without the module set up, and each item was rewritten based on concept. In contrast to this study, a study in Finland developed a five-factor model for assessing digital health competency. The model includes competence areas related to human-centered remote counseling, attitudes toward digital solutions as part of everyday work, skills in using information and communication technology, knowledge to utilize and evaluate different digital solutions, and ethical perspectives when using digital solutions [ 27 ]. The digital health model revolves around the connotation of competence, incorporating skills using remote counseling, information and communication technology, as well as attitudes and ethics. The NDASS aims to assess digital application skills and focuses on the different roles of the application of digital technologies in nursing work, which differs from the direction of the digital health competence scale. In addition, as a further contribution of this study, confirmatory factor analysis was performed to confirm the fitness of the single factor aligned with the general structure of the NDASS. The results of CFA indicated that the single-factor model with modification was considered a better fit, suggesting that the final version of the NDASS had good construct validity. Furthermore, the NDASS also had good convergent validity.

The nursing digital application scale displayed high internal consistency and split-half reliability as well as good test–retest reliability in our study, indicating that the scale was reliable and reproducible. Since cross-sectional data were used, computation of test-retest reproducibility might be an added advantage [ 39 ].

These results therefore suggest that the new scale is a suitable instrument for measuring skills in applying digital technologies among nurses, with acceptable reliability and validity. It applies to a broad group of nurses including clinical nurses, specialist nurses and nurse managers. NDASS focuses on the role of nurses in the clinic and describes their digital application skills in using digital technologies for work. Compared to previous general questions, the new scale provides respondents with the direction of thinking. Compared with scales that assess specific digital technologies, NDASS is more in line with the era of rapid digitalization. In addition, shorter and simpler questions can be more easily answered, further ensuring the reliability of the data. The Nursing Digital Application Skill Scale is a tool that can be used by clinical nurses to assess their digital skills daily. It can also guide nursing managers in developing training programs based on the differences in scores for various characteristics. For instance, the tool can be used to measure the digital gap between different populations (e.g., primary nurses and nurses-in-charge and above), enabling nursing managers to develop targeted interventions to address this gap. Furthermore, the tool can be used to assess the effectiveness of the training by measuring changes in scores before and after the training. In particular, the NDASS can be used to explore the relationships between digital skills and other variables in the subsequent studies.

Although the results of the validation of the NDASS are satisfactory, several limitations should be mentioned. For instance, nurses in our study were recruited via convenience sampling in Northwest China, which may have impacted the widespread generalization and application of NDASS to some degree. Nevertheless, the sample in our study covered the departments, years of service, and professional titles of nurses as much as possible, suggesting that the NDASS is understandable and acceptable to most nurses in China. Second, validity in online research is a well-studied concern [ 40 ]. We employed several strategies to improve the data validity, such as placing objectivity issues in the second half and conducting completion time checks, as we cannot control participants’ attention while answering questions. Third, criterion validity or predictive validity was not directly determined because a gold standard does not exist. Thus, the associations between digital application skills and other digital elements should be considered in future studies. Finally, while this single-factor short scale was considered to assess the most important digital skills required for clinical work after much discussion by the research group and the expert committee, other dimensions of the Digital Competence Framework for Citizens 2.2 (Information and data literacy, Safety, etc.) are also worthy of attention. Therefore, future research will focus on developing a multi-dimensional scale with a wider range of applicability.

The digital skills of nurses are essential for the development of medical digitization. We proposed a succinct scale with 12 items to measure nurses’ digital skills in nursing work. The test results indicate that the scale is a reliable and effective instrument with excellent psychometric properties. The NDASS is replicable and applicable for the digital skill evaluation of nurses. In addition, nursing managers can use NDASS when designing nursing digital skill training.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

Nursing Digital Application Skill Scale, ACE tool

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences

Analysis of Moment Structure

Exploratory Factor Analysis

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

Standard Deviations

Content validity index

Item level of content validity index

Scale level of content validity index

Principal component analysis

Root mean squared error of approximation

Comparative Fit Index

Normed Fit Index

Goodness-of-fit Index

Incremental Fit Index

Critical Ratio

Average Variance Extracted

Intraclass correlation coefficient

Konttila J, Siira H, Kyngäs H, Lahtinen M, Elo S, Kääriäinen M, et al. Healthcare professionals’ competence in digitalisation: a systematic review. J Clin Nurs. 2019;28(5–6):745–61. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.14710 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Ronquillo Y, Meyers A, Korvek SJ. Digital Health. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023.

Senbekov M, Saliev T, Bukeyeva Z, Almabayeva A, Zhanaliyeva M, Aitenova N, et al. The Recent Progress and Applications of Digital Technologies in Healthcare: A Review. Int J Telemed Appl. 2020;2020:8830200. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/8830200 .

Murphy J. Nursing and technology: a love/hate relationship. Nurs Econ. 2010;28(6):405–8.

PubMed Google Scholar

Gastaldi L, Corso M. Smart Healthcare Digitalization: using ICT to effectively Balance Exploration and Exploitation within hospitals. Int J Eng Bus Manage. 2012;4:9. https://doi.org/10.5772/51643 .

Article Google Scholar

Tresp V, Overhage JM, Bundschus M, Rabizadeh S, Fasching PA, Yu S. Going Digital: a Survey on Digitalization and large-Scale Data Analytics in Healthcare. Proc IEEE. 2016;104(11):2180–206.

Gupta A, Maslen C, Vindlacheruvu M, Abel RL, Bhattacharya P, Bromiley PA, et al. Digital health interventions for osteoporosis and post-fragility fracture care. Therapeutic Adv Musculoskelet Disease. 2022;14:1759720x221083523. https://doi.org/10.1177/1759720X221083523 .

Choi J, Tamí-Maury I, Cuccaro P, Kim S, Markham C. Digital Health Interventions to improve adolescent HPV vaccination: a systematic review. Vaccines. 2023;11(2):249. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11020249 .

Lewkowitz AK, Whelan AR, Ayala NK, Hardi A, Stoll C, Battle CL, et al. The effect of digital health interventions on postpartum depression or anxiety: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2024;230(1):12-43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2023.06.028 .

Karami A, Farokhzadian J, Foroughameri G. Nurses’ professional competency and organizational commitment: is it important for human resource management? PLoS ONE. 2017;12(11):e0187863.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Garfan S, Alamoodi AH, Zaidan BB, Al-Zobbi M, Hamid RA, Alwan JK, et al. Telehealth utilization during the Covid-19 pandemic: a systematic review. Comput Biol Med. 2021;138:104878. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compbiomed.2021.104878 .

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Liu C, Chen H, Zhou F, Long Q, Wu K, Lo LM, Hung TH, Liu CY, Chiou WK. Positive intervention effect of mobile health application based on mindfulness and social support theory on postpartum depression symptoms of puerperae. BMC Womens Health. 2022;22(1):413.

de la Torre-Díez I, López-Coronado M, Vaca C, Aguado JS, de Castro C. Cost-utility and cost-effectiveness studies of telemedicine, electronic, and mobile health systems in the literature: a systematic review. Telemedicine J e-health: Official J Am Telemedicine Association. 2015;21(2):81–5.

Lalanza S, Peña C, Bezos C, Yamauchi N, Taffner V, Rodrigues K, et al. Patient and Healthcare Professional insights of Home- and remote-based Clinical Assessment: a qualitative study from Spain and Brazil to determine implications for clinical trials and current practice. Adv Therapy. 2023;40(4):1670–85.

Salahuddin L, Ismail Z. Classification of antecedents towards safety use of health information technology: a systematic review. Int J Med Informatics. 2015;84(11):877–91.

de Veer AJ, Francke AL. Attitudes of nursing staff towards electronic patient records: a questionnaire survey. Int J Nurs Stud. 2010;47(7):846–54.

Golz C, Peter KA, Müller TJ, Mutschler J, Zwakhalen SMG, Hahn S. Technostress and Digital Competence among Health Professionals in Swiss Psychiatric Hospitals: cross-sectional study. JMIR Mental Health. 2021;8(11):e31408.

Tzafilkou K, Perifanou M, Economides AA. Development and validation of students’ digital competence scale (SDiCoS). Int J Educ Technol High Educ. 2022;19(1):30.

Vuorikari R, Kluzer S, Punie Y. DigComp 2.2, The Digital Competence Framework for Citizens - With new examples of knowledge, skills and attitudes. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union; 2022 https://doi.org/10.2760/490274 .

Li X, Hu R. Developing and validating the digital skills scale for school children (DSS-SC). Inform Communication Soc. 2022;25(10):1365–82.

Fan C, Wang J. Development and validation of a questionnaire to measure Digital skills of Chinese undergraduates. Sustainability. 2022;14(6):3539.

van Laar E, van Deursen AJAM, van Dijk JAGM, de Haan J. 21st-century digital skills instrument aimed at working professionals: conceptual development and empirical validation. Telematics Inform. 2018;35(8):2184–200.

Cowan DT, Jenifer Wilson-Barnett D, Norman IJ, Murrells T. Measuring nursing competence: development of a self-assessment tool for general nurses across Europe. Int J Nurs Stud. 2008;45(6):902–13.

Liu M, Kunaiktikul W, Senaratana W, Tonmukayakul O, Eriksen L. Development of competency inventory for registered nurses in the people’s Republic of China: scale development. Int J Nurs Stud. 2007;44(5):805–13.

Kinnunen UM, Heponiemi T, Rajalahti E, Ahonen O, Korhonen T, Hyppönen H. Factors Related to Health Informatics Competencies for Nurses-Results of a National Electronic Health Record Survey. Computers Inf Nursing: CIN. 2019;37(8):420–9.

Google Scholar

Turja T, Rantanen T, Oksanen A. Robot use self-efficacy in healthcare work (RUSH): development and validation of a new measure. AI Soc. 2019;34(1):137–43.

Jarva E, Oikarinen A, Andersson J, Tomietto M, Kääriäinen M, Mikkonen K. Healthcare professionals’ digital health competence and its core factors; development and psychometric testing of two instruments. Int J Med Informatics. 2023;171:104995.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Peart MT, Gutierrez-Esteban P, Cubo-Delgado S. Development of the digital and socio-civic skills (DIGISOC) questionnaire. ETR&D-EDUCATIONAL Technol Res Dev. 2020;68(6):3327–51.

He H, Li H. Development and validation of information literacy self-rating scale for clinical nurses. J Nurs Sci. 2020;35(15):56–9.

Polit DF, Beck CT, Owen SV. Is the CVI an acceptable indicator of content validity? Appraisal and recommendations. Res Nurs Health. 2007;30(4):459–67.

Pryse Y, McDaniel A, Schafer J. Psychometric analysis of two new scales: the evidence-based practice nursing leadership and work environment scales. Worldviews evidence-based Nurs. 2014;11(4):240–7.

Sapountzi-Krepia D, Zyga S, Prezerakos P, Malliarou M, Efstathiou C, Christodoulou K, Charalambous G. Kuopio University Hospital Job Satisfaction Scale (KUHJSS): its validation in the Greek language. J Nurs Adm Manag. 2017;25(1):13–21.

Batista-Foguet JM, Coenders G, Alonso J. Confirmatory factor analysis. Its role on the validation of health related questionnaires. Med Clin. 2004;122(Suppl 1):21–7. https://doi.org/10.1157/13057542 .

Prudon P. Confirmatory factor analysis as a tool in research using questionnaires: A critique. Comprehensive Psychology. 2015;4(1). https://doi.org/10.2466/03.CP.4.10 .

Osburn HG. Coefficient alpha and related internal consistency reliability coefficients. Psychol Methods. 2000;5(3):343–55. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989x.5.3.343 .

Giavarina D. Understanding bland Altman analysis. Biochemia Med. 2015;25(2):141–51.

Sloan JA, Dueck A, Qin R, Wu W, Atherton PJ, Novotny P, Liu H, Burger KN, Tan AD, Szydlo D, et al. Quality of life: the Assessment, Analysis, and interpretation of patient-reported outcomes by FAYERS, P.M. and MACHIN, D. Biometrics. 2008;64(3):996. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-0420.2008.01082_11.x .

Shi J, Mo X, Sun Z. Content validity index in scale development. Zhong Nan Da Xue Xue bao Yi xue ban. 2012;37(2):152–5. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1672-7347.2012.02.007 . (China)

Vyas S, Nagarajappa S, Dasar PL, Mishra P. Linguistic adaptation and psychometric evaluation of original oral health literacy-adult questionnaire (OHL-AQ). J Adv Med Educ Professionalism. 2016;4(4):163–9.

Paas LJ, Morren M. PLease do not answer if you are reading this: respondent attention in online panels. Mark Lett. 2018;29(1):13–21.

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all participants who voluntarily contributed to this study.

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Faculty of Nursing, Xi’an Jiaotong University Health Science Center, No.76, West Yanta Road, Xi’an, Shaanxi, 710061, China

Shijia Qin, Jianzhong Zhang, Ge Meng, Xinqi Zhuang, Yitong Jia, Wen-Xin Shi & Yin-Ping Zhang

Department of Nursing, Xi’an No.3 Hospital, The Affiliated Hospital of Northwest University, Xi’an, Shaanxi, 710018, China

Xiaomin Sun

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Y-PZ and SQ contributed to the study design and conception. Data collection and analysis were performed by JZ, XS, GM, YJ, and W-XS. The manuscript was drafted by SQ and XZ and revised by Y-PZ. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Yin-Ping Zhang .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Approval was obtained from the Ethics Committees of the First Affiliated Hospital of Xi’an Jiaotong University. The ethical approval number is XJTU1AF2023LSYY-066. All participants confirmed informed consent prior to participation.

Consent for publication

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Qin, S., Zhang, J., Sun, X. et al. A scale for measuring nursing digital application skills: a development and psychometric testing study. BMC Nurs 23 , 366 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-024-02030-8

Download citation

Received : 17 January 2024

Accepted : 20 May 2024

Published : 31 May 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-024-02030-8

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Digital skills

- Nursing digital application skill

- Scale development

- Psychometric test

BMC Nursing

ISSN: 1472-6955

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Show all results for " "

Reliability and Validity in Research Quiz

Study Flashcards

10 Questions

What is the purpose of reliability and validity in research.

To ensure consistency and accuracy of research findings

What does reliability in research refer to?

Consistency of research findings

Which type of validity compares the test results with other measures of the same construct?

Criterion-related validity

How does measurement error affect research outcomes?

It can introduce bias and reduce the accuracy of the findings

What is the purpose of credibility, auditability, and fittingness in qualitative research?

To ensure trustworthiness and authenticity of the research findings

Which of the following is a component of reliability as it relates to research?

Equivalence

What type of validity compares the test results with other measures of the same construct?

What is the process of reducing data to meaningful units (themes) in qualitative data analysis.

Data condensation

Which criterion is used to evaluate the quality of qualitative research related to credibility?

Member checking

What is the purpose of fittingness in qualitative research?

Ensuring the findings resonate with participants' experiences

Study Notes

Research validity and reliability.

- Reliability and validity are essential in research to ensure that the results are accurate, trustworthy, and generalizable to a larger population.

Reliability in Research

- Reliability refers to the consistency of the measurement tool or method in producing the same results over time.

- A reliable measure is one that produces consistent results when repeated under the same conditions.

Types of Validity

- Construct validity compares the test results with other measures of the same construct.

- It ensures that the research measure is actually measuring the concept or phenomenon it purports to measure.

Measurement Error and Research Outcomes

- Measurement error can affect research outcomes by introducing bias and reducing the accuracy of the results.

- It can lead to incorrect conclusions and faulty decision-making.

Qualitative Research Quality

- Credibility, auditability, and fittingness are essential components of qualitative research quality.

- Credibility refers to the confidence in the data and the findings.

- Auditability refers to the transparency and documentation of the research process.

- Fittingness refers to the relevance and appropriateness of the data and findings to the research context.

Reliability Components

- Consistency is a key component of reliability, referring to the ability of the measurement tool to produce consistent results.

Validity Types

- Criterion validity compares the test results with other measures of the same construct.

Qualitative Data Analysis

- Coding is the process of reducing data to meaningful units (themes) in qualitative data analysis.

Evaluating Qualitative Research

- Credibility is a criterion used to evaluate the quality of qualitative research, referring to the confidence in the data and the findings.

Fittingness in Qualitative Research

- Fittingness ensures that the data and findings are relevant and appropriate to the research context, increasing the confidence in the results.

Test your understanding of reliability and validity in research and qualitative data analysis with this quiz. Explore the concepts of stability, equivalence, and homogeneity, and compare different reliability estimates. Define and compare content, criterion-related, and construct validity to assess your knowledge in this area.

Make Your Own Quizzes and Flashcards

Convert your notes into interactive study material.

More Quizzes Like This

Quantitative and Qualitative Data Analysis

Qualitative Data Analysis Quiz for BITS Pilani Goa Campus Students

Qualitative Data Analysis: Understanding Characteristics and Attribute...

Upgrade to continue

Today's Special Offer

Save an additional 20% with coupon: SAVE20

Upgrade to a paid plan to continue

Trusted by students, educators, and businesses worldwide.