Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 25 April 2023

Relationship between depression and quality of life among students: a systematic review and meta-analysis

- Michele da Silva Valadão Fernandes 1 , 7 ,

- Carolina Rodrigues Mendonça 2 ,

- Thays Martins Vital da Silva 3 ,

- Priscilla Rayanne e Silva Noll 1 , 4 ,

- Luiz Carlos de Abreu 5 &

- Matias Noll 1 , 6

Scientific Reports volume 13 , Article number: 6715 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

12k Accesses

15 Citations

2 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Risk factors

- Signs and symptoms

The objectives of this systematic review were to estimate the prevalence of depression and to identify the relationship between depression and quality of life (QOL) among high school and university students. Literature search was performed in the Scopus, Embase, PubMed, Scielo, CINAHL and Web of Science databases, following the PRISMA methodology. The results were presented through descriptive approaches and meta-analysis. Thirty-six studies met the eligibility criteria, and twenty-six were included in the meta-analysis. The prevalence of depressive symptoms was 27% (95% CI 0.21–0.33) among students, being high school and university students was 25% (95% CI 0.14–0.37) and 27% (95% CI 0.20–0.34), respectively, and most studies have shown that depression was associated with low QOL. Among the limitations of the study is the difficulty of generalizing the results found, considering the large sample of health students. New studies should be conducted considering the severity, duration, and patterns of depressive symptoms in high school and university students, to better understand the relationship between depression and QOL.

Similar content being viewed by others

Prevalence of depression and its relationship with quality of life among university students in Macau, Hong Kong and mainland China

Association of depression and anxiety with health-related quality of life in beginning Medical Sciences Student

Prevalence of depression among Chinese university students: a systematic review and meta-analysis

Introduction.

Depression is a disorder that increasingly affects different populations, with an estimated prevalence rate of 4.4% worldwide 1 . This condition is defined as a mental disorder characterized by a persistent state of depressed mood, accompanied by other psychiatric symptoms such as fatigue and loss of energy, decreased interest or pleasure, impaired sleep, psychomotor agitation or retardation, concentration difficulties, change in appetite and weight, feelings of worthlessness or excessive guilt, or suicidal ideations 2 , 3 . Biological, psychological, cultural, and social factors can contribute to the risk of depression at some stage of life 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 . The high prevalence of depressive symptoms among high school and university students is a worrying aspect from the point of view of public health and educational policies 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , because it interferes negatively with learning, performance, and academic success 13 , 14 , in addition to increasing the global burden of diseases 3 , 15 .

High school and university students present significant risk factors for depression, since they need to deal with academic stress on a daily basis 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 . This population is extremely concerned about school performance; emotional, family, and social conflicts; anxiety; among other aspects of life, common to adolescents and young adults, who need to adapt to changes in puberty 18 , 20 , 21 , 22 . On the other hand, interaction with a supportive environment in the educational context can contribute to the prevention and remission of depressive symptoms, improving the QOL among students 23 , 24 . Although different studies have shown that depression negatively impacts the QOL 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , the relationship between the severity of depressive symptoms and QOL among high school and university students is unclear 21 , 29 .

Recent literature reviews have reported on the prevalence of depression in adolescents and their relationship with distinct biopsychosocial variables 4 , 22 , 30 , such as academic stress, sociodemographic correlates 12 , 31 , resilience 32 , school frequency 33 , and the school psychosocial climate 34 . Other reviews, with samples of university students, also prioritized the results of depression prevalence 35 , 36 and a wide variety of associated risk factors, such as sleep quality 37 , suicidal ideation 36 , 38 , sex 10 , 36 , 39 , socioeconomic status 40 , and sexual abuse 39 . No systematic reviews that analyzed the relationship between depression and QOL among high school and university students were found. The evaluation of QOL can contribute to preventive actions in the context of depression, since it is a multidimensional concept that covers well-being and satisfaction with different areas of life 41 , 42 , 43 .

Assessing the relationship between depression and QOL is important for a broader understanding of the nature of diseases people are exposed to 21 , 44 , 45 . Understanding how the different degrees of depression affect QOL and whether QOL interferes with the progression of the severity of depressive symptoms is necessary, since evidence shows that the trajectory of depressive symptoms vary within the same population 46 , 47 , 48 . Thus, the objectives of this study are: (1) to estimate the prevalence of depression among high school and university students and (2) to identify the relationship between depression and QOL among high school and university students through a systematic review of the literature and a meta-analysis. In addition, we aimed to summarize the evidence of the influence of depression and QOL on academic performance, absenteeism, and school dropout rates among these students. The consolidation of these findings is essential to identify and clarify the risk factors for depression among adolescents and young people. In this way, it will be possible to guide future research and interventions focusing on improving students' mental health.

Research questions

The main research questions guiding this systematic review are, “What is the prevalence of depression among high school and university students?” and “What is the evidence on the relationship between depression and QOL among high school and university students?” The secondary question guiding this review is “What are the influences of depression and QOL on academic performance, absenteeism, and school dropout rates among high school and university students?” If the high prevalence of depression among high school and university students is related to self-perception of quality of life, it is possible that this relationship is determined by specific dimensions of QOL and manifests itself in different ways among students.

Protocol and registration

The present systematic review was conducted according to the methodology for Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 49 , for identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion of studies. Details that are more specific can be found in the registration of the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews and in the published protocol article 50 . As the analysis was based on published articles (secondary data), ethical approval was not necessary.

This review follows the population, exposure, comparator, outcome (PECO) structure, mentioned in the recommended notification items for systematic reviews 51 . Thus, “P” represents high school and university students; “E”, depression and QOL; “C”, sex and age group; and “O”, depression and QOL 51 . Academic performance, absenteeism, and school dropout rates were also analyzed as secondary outcomes.

Search strategy and eligibility criteria

In January 2023, a researcher (reviewer 1) accessed the Scopus, Embase, PubMed, Scielo, CINAHL, and Web of Science databases, restricting the search to publications in English between 2011 and 2023. The choice to limit the search to the last 13 years was guided by the following factors: (a) focusing on recent publications in the area, particularly those that assessed depression based on the current criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental disorders (DSM-5), published in 2013 52 is more relevant, and (b) a prior analysis, based on PubMed, showed that publications and the production of research citations in this area were significantly increasing from 2011 onwards.

Table 1 shows the search strategy adapted to the different databases. The search strategy was also complemented by: (a) tracking of the references of the included studies and relevant systematic reviews, and (b) searches in Google Scholar. The main search keywords were: “high school students”, “college students” (population), “depression” (exposure/outcome) and “quality of life” (exposure/outcome).

Depression was defined as any depressive disorder based on a clinical diagnosis, according to the criteria of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 53 , 54 or the DSM 52 , or by the evaluation of depressive symptoms through a validated inventory/self-reporting questionnaire 55 , 56 . QOL was defined, according to the criteria of the World Health Organization (WHO), as “individuals’ perception of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards and concerns” 57 .

Observational studies (cross-sectional and longitudinal) with the following characteristics were included: (a) a sample of high school and university students aged 10–33 years; (b) depression and QOL as the main outcome or exposure/risk factor; (c) reported the association between depression and QOL; (d) used a standardized questionnaire for QOL or health related QOL (HRQOL); and (e) evaluation of depression/depressive symptoms with validated instruments and/or clinical diagnosis. The age range 10 to 33 years was used based on the age of adolescents and young adults (age, 10 to 24 years as defined by WHO) 57 . The age was extended to 33 years because the average age of university students is higher in recent years.

The exclusion criteria were: (a) theses, dissertations, books, book chapters, reviews, case reports, comments, letters and editorials, duplicate articles, and articles in which the full text could not be retrieved in online databases, through library requests, or by e-mails sent to the author(s) of the study; (b) studies with specific populations (pregnant and breastfeeding women, victims of violence, amputees, inpatients, and disabled people; in disaster situations, athletes, asthmatics, diabetics, and hypertensive people; patients with HIV, cancer, arthritis, cystic fibrosis, among other chronic diseases); (c) studies with samples of mixed ages, unless data could be collected, organized or calculated separately; (d) incomplete data on the association between depression and QOL; (e) clinical trials and case–control studies; and (f) when more than one article provided data on the same sample.

Training of researchers

Before beginning the screening process, the researchers who participated in the eligibility assessments were subjected to training as to the inclusion/exclusion criteria of the study, with a practical session on eligibility assessment of 50 abstracts 58 . In addition, the researchers participated in another training session to standardize the risk of bias and the analysis of Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS), evaluating five articles not included in the present study. Finally, the researchers were trained on how to correctly use the Rayyan software and standardize the procedures 58 .

Review process

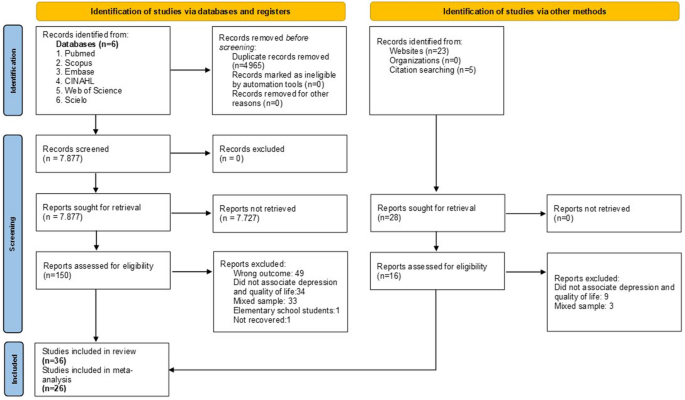

After the bibliographic search, the articles retrieved in the databases were compared and the duplicates removed using EndNote X9 (Clarivate, PA, USA). In the first phase of the review, two researchers (reviewer 1 and reviewer 2) independently sorted the titles and summaries of all articles that met the inclusion and exclusion criteria. This phase was performed using Rayyan software (Rayyan Systems Inc., Cambridge, MA, USA) in blind mode 59 . Disagreements regarding the inclusion and exclusion criteria were discussed and resolved by a third researcher (reviewer 3). In the second phase, the selected articles were fully read by two researchers (reviewer 1 and reviewer 4) and evaluated to determine their eligibility. The reliability between evaluators for the inclusion and exclusion of the studies was determined by calculating the percentage of concordance and the Cohen’s kappa coefficient 58 . Finally, the eligible articles were included in the systematic review. The reference lists of the included articles were evaluated to identify possible additional studies lost in the database searches. Figure 1 shows the flowchart of this systematic review.

Flow diagram of the selection criteria for the study. Flowchart: Adapted from the PRISMA 2020 Flow Diagram.

Risk of bias and quality assessment of individual studies

The methodological quality and risk of bias among the studies were assessed by two researchers (reviewer 1 and reviewer 2) independently and with consensus. The methodological quality of the studies was evaluated using the online version of the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluations (GRADE) tool 60 , 61 . The strength of evidence of the studies was classified into four categories: high (four circles filled), moderate (three circles filled), low (two circles filled), or very low (one circle filled) 60 , 61 . Factors such as the risk of bias, inconsistent results, indirect evidence, imprecision, and publication bias might decrease the quality of the evidence of the studies. However, the great magnitude of the effect, the dose–response gradient, and the presence of confounders in the reduction of the effect found are factors that could increase the quality of the evidence in the studies.

The NOS for observational studies 62 was used to assess the risk of bias. The adapted scale for cross-sectional (seven items) and cohort (eight items) studies consists of three dimensions that take into account the selection of participants, the comparability of the result groups, and the evaluation of the result measurements 38 . All studies could receive a maximum of one star for each item, except for comparability, in which up to two stars could be assigned. The studies were considered as having a low risk of bias (≥ 3 points) or high risk of bias (< 3 points) 38 . In addition, we assessed whether the authors provided a statement on conflicts of interest and information on ethical approval.

Data extraction and evidence synthesis

The following information was collected from the studies using a standard data extraction spreadsheet: authors, year of publication, site/country, study design, follow-up period (longitudinal studies), characteristics of the participants (sample size, sex, and age range/mean age), instruments for the assessment of depression with respective cutoff points, QOL evaluation instruments, main findings, and association values.

Data regarding the prevalence of depression and association measures were collected, in addition to other additional results that refer to factors associated with depression and QOL. The results were categorized into two groups: (a) high school students and (b) university students. Data were collected and evaluated by two independent researchers (reviewer 1 and reviewer 4) and disagreements were resolved by a third researcher (reviewer 2).

The prevalence of depression and the results of the association between depression and QOL among students are presented as the main outcomes. The results of the prevalence of depression in the studies analyzed were presented according to the intensity of depressive symptoms. The different QOL domains evaluated were also considered in synthesizing the evidence. Secondary results are presented, including additional variables that are associated with students’ depression and QOL. We also described whether the studies presented results on the influence of depression and QOL on academic performance, absenteeism, and evasion. When possible, the differences between the sexes and age groups in terms of the prevalence of depression and the level of QOL among the students were compared.

Meta-analysis

A meta-analysis was conducted using the random effects model with data on the prevalence of depression among high school students, depression among university students, and moderate and low QOL. The data are graphically displayed in Forest plots, showing prevalence rates with their 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Publication bias was evaluated using Egger’s test. All analyses were conducted using Stata version 16.0 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, USA).

Literature search and study selection

Figure 1 shows the selection process for this systematic review. In all, 12,842 articles were identified based on the eligibility criteria, and 28 additional articles were identified through lists of references and manual searches. After excluding duplicate articles, 7,877 articles were selected for title and abstract reading. There was moderate agreement (agreement = 99.4%, kappa = 0.60) between researchers and 150 articles remained for full text evaluation. After the full text analysis, 36 studies met the eligibility criteria and were included in the systematic review (Fig. 1 ). The articles included analyzed depression and QOL among high school and university students and provided information on the relationship between depression and QOL (Table 2 ) 44 , 63 , 64 , 65 , 66 , 67 , 68 , 69 , 70 , 71 , 72 , 73 , 74 , 75 , 76 , 77 , 78 , 79 , 80 , 81 , 82 , 83 , 84 , 85 , 86 , 87 , 88 , 89 , 90 , 91 , 92 , 93 , 94 , 95 , 96 , 97 .

Risk of bias and quality of the evidence

The NOS scale scores ranged from three to nine points. The classification of studies with lower scores 44 , 67 , 70 , 81 was related to unclear description of confounding factors, unadjusted results for confounders, and comparability between respondents and non-respondents characteristic. All studies reached scores ≥ 3 and were evaluated as having low risk of bias (Table 2 ).

The strength of the evidence classified using the GRADE methodology indicated that the studies had low (n = 19, 53%), moderate (n = 13, 36%), and high (n = 4, 11%) quality (Table 2 ). The low and moderate quality was justified by the inaccuracy of the results of observational studies, the reduced sample size, and the effect produced by these studies. Seven studies 67 , 70 , 71 , 81 , 88 , 90 , 95 , 97 did not clearly specify conflicts of interest, and two studies did not report whether ethical approval was obtained 71 , 89 (Table 2 ).

Characteristics of the studies

Table 3 presents the characteristics of the studies included in the review, grouped into the following categories: year of publication, region, study design, students' study modality, sample size and types of assessment instruments for depressive symptoms/depression and QOL. This review included studies of students of 20 nationalities and a total sample of 24,704 people. Most studies were published between 2014 and 2020 (n = 20, 55.6%), mainly with the Asian population (n = 21, 58.3%), and university students (n = 27, 75%). With the exception of a single study, all studies included samples of both sexes. The study design mainly covered cross-sectional studies (n = 15, 93.8%), with only one longitudinal study 93 . The sample size ranged from 40 participants 88 to 4,467 participants 92 , 75.0% of whom were university students (Table 3 ). The mean age of high school students ranged from 13.2 (± 2.1) 70 to 16.9 (± 1.2) years 92 , while the mean age of university students ranged from 19.0 (± 1.1) 63 to 22.8 (± 3.0) years 63 . Most of the studies included a sample of medical students 63 , 64 , 65 , 67 , 76 , 79 , 81 , 82 , 87 , 89 , 93 , 96 nursing students 80 , 95 , and health students 68 , 73 , 78 , 85 , 88 , 94 . Only six studies included a large sample of university students 44 , 66 , 69 , 84 , 86 , 97 . No study evaluated the possible influences of depression and QOL on academic performance, absenteeism, and school dropout.

Characteristics of results and main findings

The characteristics and main results are presented separately for the evaluation of depression and QOL among students, prevalence of depression and its relationship with QOL among students, other factors associated with depression and QOL among students, and meta-analysis.

Evaluation of depression and quality of life among students

Table 3 shows a summary of the instruments used to assess depressive symptoms and Table 4 lists the respective cutoff points adopted in each study. The most widely used instrument for assessing depression and depressive symptoms was the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) (n = 9, 25.0%), with cutoff points ranging from ≥ 10 to > 15 for the presence of depressive symptoms. Other studies used a variety of instruments to assess depression and depressive symptoms, including the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS-21) (n = 6, 16.7%) and the Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale (ZUNG SDS) (n = 2, 5.5%) 65 , 85 .

Twelve studies did not specify the cutoff points adopted for the evaluation of depressive symptoms 44 , 68 , 69 , 70 , 76 , 79 , 82 , 89 , 91 , 92 , 93 , 97 . There were no studies based on the clinical diagnosis of depression, and the evaluation of depressive symptoms is prevalent through self-reporting questionnaires. The severity of depressive symptoms was evaluated only in eight studies 64 , 65 , 67 , 83 , 84 , 90 , 96 , 97 , in which the prevalence of depressive symptoms was categorized into mild, moderate, and severe/significant symptoms.

For the QOL evaluation, the most widely used instrument was the World Health Organization QOL Questionnaire (WHOQOL; WHOQOL-BREF) (n = 19, 52.8%), followed by the RAND 36-item Short Form Survey (SF-36) (n = 7, 19.4%), as specified in Table 3 . The different QOL domains evaluated by the main instruments covered the physical, environmental, psychological, and social domains (WHOQOL; WHOQOL-BREF, and SF-36), and the sub-domains related to functional capacity, general health perceptions, bodily pain, vitality, social, physical, and mental functioning, and limitations caused by emotional problems (SF-36). Although there was a certain tendency for studies to assess QOL from different domains, ten studies did not analyze these domains/sub-domains 44 , 66 , 68 , 71 , 72 , 74 , 78 , 85 , 88 , 89 .

Prevalence of depression and its relation to students’ quality of life

Table 4 shows a summary of the results on the prevalence of depression and its relationship with the students’ QOL, categorized by high school and university students, by the intensity of depressive symptoms and by instruments used in the evaluation of depression and QOL. The prevalence of depressive symptoms among high school students ranged from 8.5% among French students 71 to 43.4% among Brazilian students 77 . Among college students, the prevalence of depressive symptoms ranged from 3.3% among Indonesian students 81 to 61% among Malaysian and Brazilian students 83 , 96 . Table 5 shows the main results on the relationship between depression and QoL. Association/correlation tests for each study can be found in Supplementary File 1 .

Studies with a sample of high school students identified that QoL is negatively correlated with depression (n = 8, 100%). Only one study showed that, regarding the QoL domains, the financial resources and social support dimensions were not correlated with depression among students from Mexico 75 . In general, studies with a sample of university students found that depression is associated with low QoL (n = 11, 40.7%). In addition, depression was a predictor of QoL and vice versa. On the other hand, other studies (n = 6, 22.2%) present a varied behavior regarding the relationship between different QOL domains and the prevalence of depressive symptoms. In Thai and Malaysian students, for example, depression was associated only with the psychological and physical domains of QOL 64 , 67 , while a study with a sample of 193 Brazilian students indicated that the physical domain of QOL was unaffected by depression 96 . In two studies depression is not correlated with QOL 68 , 85 .

Three studies analyzed the relationship between depressive symptoms and QOL among German, Brazilian and Pakistani students with a longitudinal design 78 , 88 , 93 . The German students showed an increase in depression symptoms over the semesters, with highly significant correlations between depression and mental quality of life 78 . The presence of depressive symptoms among Brazilian students was negatively related to QOL in all domains, except for the physical domain 93 . It also showed that students with depression at the beginning of graduation tend to maintain depressive symptoms over time, contributing to a worse future QOL 93 . Female students were more likely to have a worse physical QOL over time 93 . On the other hand, students with depression showed improvement in QoL during the COVID-19 epidemic lockdown in Pakistan 88 .

Other factors associated with depression and quality of life among students

In addition to the main results of interest, the studies presented other important variables that are associated with depression and QOL among students, such as anxiety and academic stress. According to one study, self-esteem was positively correlated with QOL, while anxiety symptoms, and relationship with their parents were negatively correlated with QOL in high school students 92 . Another study analyzed that QOL was also correlated with low and moderate anxiety, with a high level of general well-being and with low/moderate level of educational stress 74 .

Studies have shown that among university students, QOL was negatively correlated with anxiety 44 , 67 , 94 and emotional control 44 , and positively correlated with general positive affection, emotional bonds, life satisfaction 44 , and family income 97 . Students who engaged in physical activity every day had higher scores on the HRQOL 97 .

The frequency of depressive symptoms increased with increased anxiety 63 , 85 , academic stress, sleep disorders, academic pressure 66 , and perceived stress 85 . Students with depression had higher scores for social phobia 63 and the intensity of depressive symptoms was higher in the last year of their undergraduate course 95 . In a sample of Chinese students, depression was more prevalent among medical students, followed by engineering and arts students 69 .

Seven studies evaluated depression and QOL of students during the COVID-19 pandemic 70 , 73 , 75 , 77 , 81 , 84 , 88 . In the pandemic period, the prevalence of depression ranged from 21.2% among Mexican high school students 75 to 57.9% among Indonesian university students 84 . It was observed that the COVID-19 pandemic negatively affected the mental health and QOL of students 73 , 88 and that depression symptoms were associated with poor quality of life and social isolation 70 , 75 , 77 , 81 , 88 .

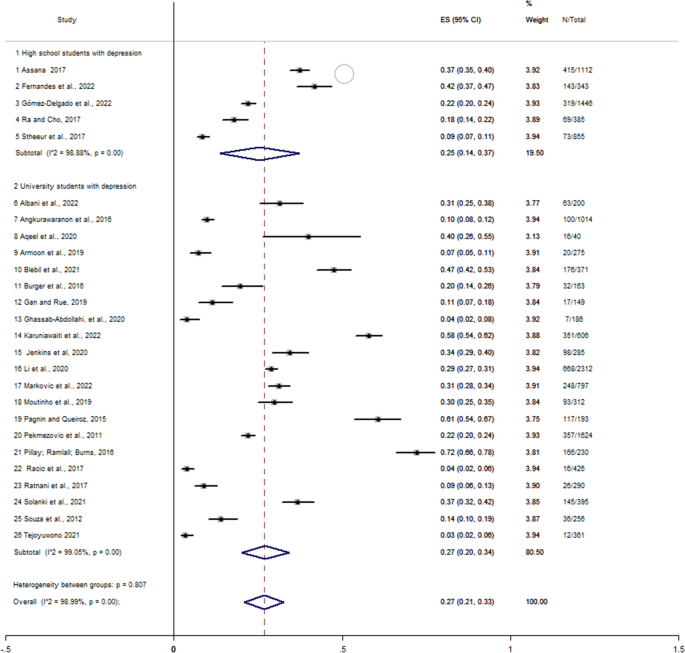

Figure 2 shows the combined prevalence of depression among high school students and depression among university students. The combined prevalence of depression among students was 27% (95% CI 0.21–0.33). The prevalence of depression among High school students was 25% (95% CI 0.14–0.37). The prevalence of depression among university students was 27% (95% CI 0.20–0.34).

Forest plot evaluating the prevalence of depression in students, using data from 26 studies. Flowchart: Elaborated by the authors.

There was a high level of statistical heterogeneity ( I 2 = 99.40%, p < 0.001). Heterogeneity had an influence on the result of the analysis. Evidence of publication bias in the meta-analysis of the combined prevalence was found using the Egger’s regression test ( p = 0.000).

In the meta-analysis, involving three studies, the odds ratio for the association between depression and quality of life in students was 0.009 (95% CI − 0.009 to 0.027), ( I 2 = 95.6%, p < 0.01), not indicating a positive association 68 , 74 , 85 .

The present study systematically estimated the prevalence of depression and summarized the relationship between depression and QOL among high school and university students. The prevalence of depressive symptoms was 27% among students and most studies have shown that depressive symptoms was associated with a low QOL. Despite being relevant to research involving students, the studies did not evaluate the influence of depression and QOL on academic performance, absenteeism, and school dropout rates.

The main results show that the estimated prevalence rate of depression among university students was 27%, similar to the results of other meta-analyses that present the prevalence of depressive symptoms of 24.4% to 34.0% with the same population 11 , 35 , 36 , 38 , 40 . About 25% of high school students had depressive symptoms. Indonesian and Brazilian high school students had a higher prevalence of depressive symptoms compared to students from Mexico, Republic of Korea and France. Differences in the prevalence of depression can also be observed in different studies, where the prevalence of depression was in Chinese, 24.3% 12 , Pakistani (17.2%), and Malaysian (26.2%) students 98 , 99 . However, high school students in Indonesia had a higher prevalence of depressive symptoms, with rates of 52.7% 100 .

The findings of this review also demonstrate that high school and university students present a higher prevalence of depressive symptoms compared to large samples in distinct communities, ranging from 7.3% in countries like Australia to 20.6% in South American countries 101 . Estimates of a 12-month depression prevalence in adolescents and young adults in the United States range from 8.7% to 11.3% 102 , rates lower compared to those found in the present review.

The manifestations of depressive symptoms are not static, and they affect a distinct population of students 45 , 93 , since there are several biological, psychological, and social factors that contribute to the risk of depression, including cultural determinants that are present in the person’s life such as the context of development, parental practices, and temperament 48 , 98 . Part of the challenge relates to the heterogeneous nature of the diagnosis and condition of depression. There is an emerging notion that mood disorders lie on a spectrum 103 . In addition, individuals of different ethnicities may express depression differently. Chinese, for example, tend to deny mental health symptoms or express them somatically 104 . Given the complexity of identifying protection mechanisms and risk factors, research suggests that the dimensions of subjective well-being are complementary aspects of the evaluation of depression symptoms 25 , 105 , 106 . In addition, QOL is an important indicator for identifying groups vulnerable to depressive symptoms and the golden objective for treating depression is to improve QOL 21 .

In this review, 97.2% of the studies showed some type of association between depression and QOL, indicating that students with depressive symptoms tend to have worse QOL, or that QOL is a predictor of depression. The role of depressive symptoms as a negative predictor of QOL was documented in other reviews with adolescents 9 and university students 107 . However, the main relevance of the present study is the fact that depressive symptoms may not impact in the same way in the different domains of QOL 64 , 67 , 93 , 96 . The psychological dimension of the QOL of students seems to be the most affected; however, it is not possible to state precisely that it does not occur with the physical, environmental, and social dimensions of the QOL. This is because other factors associated with depression and QOL must be considered, such as the presence of chronic or physical diseases, for example 108 .

Data from the meta-analysis indicate that there is no positive association between depression and QOL in students, showing a possible influence of other mediators on the relationship between depression and QOL. Some people, despite experiencing depressive symptoms at some stage of life, may present adaptive mechanisms that allow them to self-manage mental suffering and demonstrate resilience 32 , 43 , 98 , 109 , 110 , 111 , 112 . The influence of different degrees of depressive symptoms may also compromise the analysis of results, but studies do not provide enough data to support this statement. Therefore, these findings are limited in clarifying the wide and complex relationship between depression and QOL among students. Further studies are needed, mainly with longitudinal design and with quality evidence.

With regard to QOL, the perception of QOL can be more positive or negative as for the meanings each person attributes to their life experiences 111 , 113 , 114 , 115 , 116 To better understand these aspects, the evaluation of QOL should consider the relationship between positive and negative psychological dimensions as independent but at the same time inter-related dimensions 25 . In this sense, a favorable educational environment may play a “barrier” role in negative psychological dimensions among students, such as stress 25 . The psychological, physical, environmental, and social domains of QOL present important differences when analyzed in terms of sex and geographic region 64 , 93 , 95 . Female students tend to present worse QOL, in addition to having the most impaired physical domain of QOL 93 , 96 , 117 , a condition that may be associated with the probability of women exercising less than men 118 . This can also be explained by the fact that different instruments are used in the evaluation of QOL and by adverse cultural or social factors.

This study also showed that students experienced intense depressive symptoms and worsened QOL during the COVID-19 pandemic. Since the establishment of social distancing/isolation measures due to the COVID-19 pandemic caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus, students have shown considerable increases in depressive symptoms and anxiety 119 , 120 . In part, this is due to prolonged social isolation, bereavement, violence in the family context, and excessive use of the internet and social networks 121 , 122 , 123 , 124 , 125 , 126 . The existence of social distancing implemented to prevent the spread of the COVID-19 virus caused limitations in physical and social activities, including leisure activities and in the sufficiency of the family's financial 127 . In addition, the blockade and closure of schools and universities forced students to study at home, which may have contributed to increased symptoms of depression and consequent worsening of QOL 127 , 128 .

This review had some limitations. First, the assessment of depression and QOL in the studies considered different instruments, which made comparison of results difficult. Second, the most widely used instrument for the evaluation of depressive symptoms, the BDI, presented different cutoff points in the selected studies, which may reflect probable bias. In addition, screening tools are criticized for having a greater chance of false-positive results, making the burden of the disease seem worse 129 . Depressive symptoms were measured using psychometric tools that indicated the presence or absence of symptoms, but they were not able to diagnose depression. A clinical evaluation would be essential to better understand and standardize the results 21 , 42 . Third, most studies used a cross-sectional design, which does not allow definitive conclusions on causality. Longitudinal studies could demonstrate whether poor QOL is a predictor of depression or whether depression is a predictor of low QOL, in addition to clarifying how the intensity of depressive symptoms interacts with QOL and vice-versa. Fourth, the results cannot be generalized since most participants are medical, nursing and health students. Fifth, excluding gray research sources from our systematic review may resulted in loss of information on the subject. So, for future studies, we suggest to take into account the possibility to include a gray literature search as a step of the search strategy. Finally, the studies did not analyze important factors mediating in the relationship between QOL and mental health, such as socioeconomic level, stress, coping style, and personality 112 , 130 , 131 .

The strengths of this study include the specific assessment of depression, to the detriment of a wide scope of mental health problems, which allows a particular analysis of its relationship with QOL. Results from the analysis of conflicts of interest and ethical approvals, which are often omitted from the assessments, are also presented here. A meta-analysis was conducted to provide a general estimate of the prevalence of depression among high school and university students. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first systematic review that summarizes the evidence on the relationship between depression and QOL among high school and university students, allowing us to clarify the gaps in the literature and propose recommendations for future research. In addition, this is the first study that intended to analyze academic consequences, such as academic performance, absenteeism, and school dropout. However, the studies included in this review did not analyze these aspects, which indicate a lack of research on the academic consequences, from the perspective of the relationship between depression and QOL.

New studies should be conducted considering the severity, duration, and patterns of depressive symptoms in high school and university students, to better understand the relationship between depression and QOL. Future research directions also include in-depth study on the relationship between depressive symptoms and specific dimensions of QOL, considering its domains and sub-domains, identification of sociodemographic variables and the influence of coping mechanisms on the relationship between depression and QOL, and longitudinal assessment of the relationship between depression and QOL among students. Health professionals and education professionals must better understand the different aspects of the life of students who are depressed, being able to determine its origin and the protection mechanisms that can be used in punctual interventions 68 , 131 .

Depression is associated with the QOL of students; however, the relationship between depression and QOL is not clear yet. There is a need to understand whether QOL can affect the nature, duration, and intensity of depressive symptoms and the real impact of depressive symptoms on different QOL domains. The consolidation of these findings is fundamental to a more effective and integrated orientation of public health and education policies, focusing on promoting mental health and improving the students’ QOL. The multidimensional aspect that refers to the students’ mental health and QOL should be considered from a multidisciplinary and global conception, with the participation of health professionals, education professionals and the family in social and instrumental support, thus contributing to students’ academic performance and success.

Data availability

Due to sensitive data, the data can be accessed upon request to the authors ([email protected] (MSVF); [email protected] (MN)).

Friedrich, M. J. Depression is the leading cause of disability around the world. JAMA 317 , 1517 (2017).

PubMed Google Scholar

Pratt, L. A. & Brody, D. J. Depression in the U.S. Household Population, 2009–2012. NCHS Data Brief 60 , 1–8 (2014).

Google Scholar

Penninx, B. W. J. H., Milaneschi, Y., Lamers, F. & Vogelzangs, N. Understanding the somatic consequences of depression: Biological mechanisms and the role of depression symptom profile. BMC Med. 11 , 1–14 (2013).

Article Google Scholar

Cairns, K. E., Yap, M. B. H., Pilkington, P. D. & Jorm, A. F. Risk and protective factors for depression that adolescents can modify: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. J. Affect. Disord. 169 , 61–75 (2014).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Holtmann, M. et al. Adolescent depression: Study protocol for a randomized, controlled, double-blind multicenter parallel group trial of Bright Light Therapy in a naturalistic inpatient setting (DeLight). Trials 19 , 1–11 (2018).

Werner-Seidler, A., Perry, Y., Calear, A. L., Newby, J. M. & Christensen, H. School-based depression and anxiety prevention programs for young people: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 51 , 30–47 (2017).

Escobar, D. F. S. S., Noll, P. R. e S., Jesus, T. F. de & Noll, M. Assessing the Mental Health of Brazilian Students Involved in Risky Behaviors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17 , 3647 (2020).

Avenevoli, S., Swendsen, J., He, J. P., Burstein, M. & Merikangas, K. R. Major depression in the national comorbidity survey-adolescent supplement: prevalence, correlates, and treatment. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 54 , 37-44.e2 (2015).

Bertha, E. A. & Balázs, J. Subthreshold depression in adolescence: a systematic review. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 22 , 589–603 (2013).

Moeini, B., Bashirian, S., Soltanian, A. R., Ghaleiha, A. & Taheri, M. Prevalence of depression and its associated sociodemographic factors among Iranian female adolescents in secondary schools. BMC Psychol. 7 , 1–11 (2019).

Sarokhani, D. et al. Prevalence of depression among university students: A systematic review and meta-analysis study. Depress. Res. Treat. 2013 , (2013).

Tang, X., Tang, S., Ren, Z. & Wong, D. F. K. Prevalence of depressive symptoms among adolescents in secondary school in mainland China: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 245 , 498–507 (2019).

Fiorilli, C., De Stasio, S., Di Chiacchio, C., Pepe, A. & Salmela-Aro, K. School burnout, depressive symptoms and engagement: Their combined effect on student achievement. Int. J. Educ. Res. 84 , 1–12 (2017).

Faeq, D. T. Prevalence of depression among students :critical review. Polytech. J. 8 , 111–131 (2018).

Mokdad, A. H. et al. Global burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors for young people’s health during 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 387 , 2383–2401 (2016).

Pascoe, M. C., Hetrick, S. E. & Parker, A. G. The impact of stress on students in secondary school and higher education. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 25 , 104–112 (2020).

Reisbig, A. M. J. et al. A study of depression and anxiety, general health, and academic performance in three cohorts of veterinary medical students across the first three semesters of veterinary school. J. Vet. Med. Educ. 39 , 341–358 (2012).

Moilanen, S., Autio, L., Tolvanen, A., Sevón, E. & Rönkä, A. From intense to leisurely study days: A diary study of daily wellbeing among students in higher education. Open Educ. Stud. 2 , 295–311 (2021).

Kafle, B., Bagale, Y., Kadhum, M. & Molodynski, A. Mental health and burnout in Nepalese medical students: an observational study. Middle East Curr. Psychiatry 28 , 53 (2021).

Escobar, D. F. S. S., Jesus, T. F. de, Noll, P. R. e S. & Noll, M. Family and School Context: Effects on the Mental Health of Brazilian Students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17 , 6042 (2020).

Tang, A. L. & Thomas, S. J. Relationships between depressive symptoms, other psychological symptoms, and quality of life. Psychiatry Res. 289 , 113049 (2020).

Tang, X., Tang, S., Ren, Z. & Wong, D. F. K. Psychosocial risk factors associated with depressive symptoms among adolescents in secondary schools in mainland china: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 263 , 155–165 (2020).

Wang, M. T., Chow, A., Hofkens, T. & Salmela-Aro, K. The trajectories of student emotional engagement and school burnout with academic and psychological development: Findings from Finnish adolescents. Learn. Instr. 36 , 57–65 (2015).

Sancassiani, F. et al. Enhancing the emotional and social skills of the youth to promote their wellbeing and positive development: A systematic review of universal school-based randomized controlled trials. Clin. Pract. Epidemiol. Ment. Heal. 11 , 21–40 (2015).

Freire, T. & Ferreira, G. Health-related quality of life of adolescents: Relations with positive and negative psychological dimensions. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 23 , 11–24 (2018).

Kasteenpohja, T. et al. Outcome of depressive and anxiety disorders among young adults: Results from the Longitudinal Finnish Health 2011 Study. Nord. J. Psychiatry 72 , 205–213 (2018).

Domantay, J. A. A. Health-related quality of life of future physicians at a medical school in the Philippines: A cross-sectional study. SAGE Open 4 , 1–9 (2014).

Gazibara, T., Pekmezović, T., Popović, A., Paunić, M. & Kisić-Tepavčević, D. Chronic diseases among university students: Prevalence, patterns and impact on health-related quality of life. Vojnosanit. Pregl. 75 , 1178–1184 (2018).

Kamenov, K., Cabello, M., Coenen, M. & Ayuso-Mateos, J. L. How much do we know about the functional effectiveness of interventions for depression? A systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 188 , 89–96 (2015).

Clayborne, Z. M., Varin, M. & Colman, I. Systematic review and meta-analysis: adolescent depression and long-term psychosocial outcomes. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 58 , 72–79 (2019).

Dardas, L. A., Bailey, D. E. & Simmons, L. A. Adolescent depression in the arab region: a systematic literature review. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 37 , 569–585 (2016).

Yuen, W. W. Y., Liu, L. L. & Tse, S. Adolescent mental health problems in Hong Kong: a critical review on prevalence, psychosocial correlates, and prevention. J. Adolesc. Heal. 64 , S73–S85 (2019).

Finning, K. et al. The association between child and adolescent depression and poor attendance at school: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 245 , 928–938 (2019).

Aldridge, J. M. & McChesney, K. The relationships between school climate and adolescent mental health and wellbeing: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Educ. Res. 88 , 121–145 (2018).

Tung, Y. J., Lo, K. K. H., Ho, R. C. M. & Tam, W. S. W. Prevalence of depression among nursing students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nurse Educ. Today 63 , 119–129 (2018).

Puthran, R., Zhang, M. W. B., Tam, W. W. & Ho, R. C. Prevalence of depression amongst medical students: A meta-analysis. Med. Educ. 50 , 456–468 (2016).

Dinis, J. & Bragança, M. Quality of sleep and depression in college students: A systematic review. Sleep Sci. 11 , 290–301 (2018).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Rotenstein, L. S. et al. Prevalence of depression, depressive symptoms, and suicidal ideation among medical students a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA J. Am. Med. Assoc. 316 , 2214–2236 (2016).

Liu, Y. et al. Predictors of depressive symptoms in college students: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. J. Affect. Disord. 244 , 196–208 (2019).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Akhtar, P. et al. Prevalence of depression among university students in low and middle income countries (LMICs): A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 274 , 911–919 (2020).

Izutsu, T., Tsutsumi, A., Islam, A. & Kato, S. Mental health, quality of life, and nutritional status of adolescents in Dhaka, Bangladesh: Comparison between an urban slum and a non-slum area. Soc. Sci. Med. 63 , 1477–1488 (2006).

Carreira, H., Williams, R., Strongman, H. & Bhaskaran, K. Identification of mental health and quality of life outcomes in primary care databases in the UK: A systematic review. BMJ Open 9 , e029227 (2019).

Geng, Y., Gu, J., Zhu, X., Yang, M. & Shi, D. Negative emotions and quality of life among adolescents: A moderated mediation model. Int. J. Clin. Heal. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijchp.2020.02.001 (2020).

Cleofas, J. V. Student involvement, mental health and quality of life of college students in a selected university in Manila, Philippines. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 25 , 435–447 (2020).

Lucchetti, G. et al. Cross-cultural differences in mental health, quality of life, empathy, and burnout between US and Brazilian Medical Students. Acad. Psychiatry 42 , 62–67 (2018).

Shore, L., Toumbourou, J. W., Lewis, A. J. & Kremer, P. Review: longitudinal trajectories of child and adolescent depressive symptoms and their predictors—A systematic review and meta-analysis. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 23 , 107–120 (2018).

Wilson, S., Hicks, B. M., Foster, K. T., McGue, M. & Iacono, W. G. Age of onset and course of major depressive disorder: Associations with psychosocial functioning outcomes in adulthood. Psychol. Med. 45 , 505–514 (2015).

Ellis, R. E. R. et al. Longitudinal trajectories of depression symptoms in adolescence: psychosocial risk factors and outcomes. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 48 , 554–571 (2017).

Moher, D. et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 6 , e1000097 (2009).

Fernandes, M. da S. V., Mendonça, C. R., Silva, T. M. V. da & Noll, M. The relationship between depression and quality of life in students and the academic consequences: Protocol for a systematic review with meta-analysis. Int. J. Educ. Res. 109 , (2021).

Morgan, R. L., Whaley, P., Thayer, K. A. & Schünemann, H. J. Identifying the PECO: A framework for formulating good questions to explore the association of environmental and other exposures with health outcomes. Environ. Int. 121 , 1027–1031 (2018).

APA. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders - DSM-5 . vol. 11 (2014).

World Health Organization. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems . (2019).

World Health Organization. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems . (1993).

Andreas, J. B. & Brunborg, G. S. Depressive symptomatology among Norwegian adolescent boys and girls: The patient health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) psychometric properties and correlates. Front. Psychol. 8 , 1–11 (2017).

Nabbe, P. et al. Which DSM validated tools for diagnosing depression are usable in primary care research? A systematic literature review. Eur. Psychiatry 39 , 99–105 (2017).

World Heath Organization. The world health organization quality of life assessment (WHOQOL): Position paper from the World Health Organization. Soc. Sci. Med. 41 , 1403–1409 (1995).

Noll, M., Wedderkopp, N., Mendonça, C. R. & Kjaer, P. Motor performance and back pain in children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis protocol. Syst. Rev. 9 , 4–9 (2020).

Ouzzani, M., Hammady, H., Fedorowicz, Z. & Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan-a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 5 , 1–10 (2016).

Guyatt, G. et al. GRADE guidelines: 1. Introduction—GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 64 , 383–394 (2011).

Balshem, H. et al. GRADE guidelines: 3. Rating the quality of evidence. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 64 , 401–406 (2011).

Stang, A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 25 , 603–605 (2010).

Ratnani, I. et al. Association of social anxiety disorder with depression and quality of life among medical undergraduate students. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 6 , 243 (2017).

Angkurawaranon, C. et al. Predictors of quality of life of medical students and a comparison with quality of life of adult health care workers in Thailand. Springerplus 5 , (2016).

Pillay, N., Ramlall, S. & Burns, J. K. Spirituality, depression and quality of life in medical students in KwaZulu-Natal. S. Afr. J. Psychiatry 22 , 1–6 (2016).

Li, L. et al. Prevalence of depression and its relationship with quality of life among university students in Macau, Hong Kong and mainland China. Sci. Rep. 10 , 1–8 (2020).

ADS Google Scholar

Gan, G. G. & Hue, Y. L. Anxiety, depression and quality of life of medical students in Malaysia. Med. J. Malays. 74 , 57–61 (2019).

CAS Google Scholar

Armoon, B., Mokhayeri, Y., Haroni, J., Karimy, M. & Noroozi, M. How is the quality of life of students?: The role of depression, anxiety and stress. Polish Psychol. Bull. 50 , 43–48 (2019).

Singh, R., Shriyan, R., Sharma, R. & Das, S. Pilot study to assess the quality of life, sleepiness and mood disorders among first year undergraduate students of medical, engineering and arts. J. Clin. Diagnostic Res. 10 , JC01–JC05 (2016).

Tekin, U. Evaluation of psychosocial symptoms in adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic in turkey by comparing them with the pre-pandemic situation and its relationship with quality of life. Med. J. Bakirkoy 18 , 348–355 (2022).

Stheneur, C. et al. Sleep duration, quality of life and depression in adolescents: A school-based survey. Minerva Pediatr. 71 , 125–134 (2019).

Ra, J. S. & Cho, Y. H. Depression moderates the relationship between body image and health-related quality of life in adolescent girls. J. Child Fam. Stud. 26 , 1799–1807 (2017).

Milošević Marković, M. et al. Mental health and quality of life among dental students during COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19 , 14061 (2022).

Assana, S., Laohasiriwong, W. & Rangseekajee, P. Quality of life, mental health and educational stress of high school students in the northeast of Thailand. J. Clin. Diagnostic Res. 11 , VC01–VC06 (2017).

Gómez-Delgado, G., Almaraz-Vega, E., Ramírez-Mireles, J. E., Gutiérrez-Paredes, M. E. & Padilla-Galindo, M. del R. Health-Related Quality of Life and Depressive Symptomatology in High School Students during the Lockdown Period Due to SARS-CoV-2. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19 , 0–8 (2022).

Ghassab-Abdollahi, N. et al. Association of quality of life with physical activity, depression, and demographic characteristics and its predictors among medical students. J. Educ. Health Promot. https://doi.org/10.4103/jehp.jehp (2020).

Fernandes, M. da S. V., da Silva, T. M. V., Noll, P. R. E. S., de Almeida, A. A. & Noll, M. Depressive Symptoms and Their Associated Factors in Vocational–Technical School Students during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19 , 1–20 (2022).

Burger, P. H. M., Neumann, C., Ropohl, A., Paulsen, F. & Scholz, M. Development of depression and deterioration in quality of life in German dental medical students in preclinical semesters. Ann. Anat. 208 , 183–186 (2016).

Borges, G. B. M., Eidt, I., Zilli, L. N., Michels, A. M. M. P. & Diaz, A. P. According to graduation phase. Trends Psychiatry Psychother. 42 , 74–81 (2020).

Albani, E. et al. The impact of mental health, subjective happiness and religious coping on the quality of life of nursing students during the covid-19 pandemic. Wiad. Lek. 75 , 678–684 (2022).

Tejoyuwono, A. A. T., Nugraha, R. P. & Fahdi, F. K. The effect of mental health status on the quality of life of faculty of medicine students during the pandemic coronavirus disease 2019 period. Open Access Maced. J. Med. Sci. 9 , 645–652 (2021).

Miguel, A. Q. C., Tempski, P., Kobayasi, R., Mayer, F. B. & Martins, M. A. Predictive factors of quality of life among medical students: results from a multicentric study. BMC Psychol. 9 , 36 (2021).

Blebil, A., Dujaili, J., Mohammed, A. H., Cheong, C. M. & Hoo, Y. The effect of stress and depression on quality of life of pharmacy students in Malaysia. Pharm. Educ. 21 , 323–333 (2021).

Karuniawati, H. et al. Assessment of Mental Health and Quality of Life Status of Undergraduate Students in Indonesia during COVID-19 Outbreak: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19 , 12011 (2022).

Racic, M. et al. Self-perceived stress in relation to anxiety, depression and health-related quality of life among health professions students: a cross-sectional study from Bosnia and Herzegovina Samo-Zaznava Stresa V Povezavi Z Anksioznostjo, Depresijo in Z Zdravjem Pove. Zdr Varst 56 , 251–259 (2017).

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Wen, L.-Y. et al. Associations between Chinese college students’ anxiety and depression: A chain mediation analysis. PLoS ONE 17 , e0268773 (2022).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Solanki, H. K., Awasthi, S., Kaur, A. & Pamei, G. Depression, its correlates and quality of life of undergraduate medical students in the Kumaon region of Uttarakhand state, India. Indian J. Community Heal. 33 , 357–363 (2021).

Aqeel, M., Rehna, T., Shuja, K. H. & Abbas, J. Comparison of students’ mental wellbeing, anxiety, depression, and quality of life during COVID-19’s full and partial (smart) lockdowns: a follow-up study at a 5-month interval. Front. Psychiatry 13 (2022).

Alvi, S. M., Ali, S.A.-E.-Z., Ansari, D. S., Hassan, B. & Iqbal, N. Role of quality of life in internalizing psychological problems: A comparative study of male and female medical students. Rawal Med. J. 45 , 955–958 (2020).

Yang, Z. et al. The quality of life and its relationship with systemic family dynamics and mental health in senior high school students from Shaanxi, China. Front. Public Heal. 10 (2022).

Shin, H., Jeon, S. & Cho, I. Factors influencing health-related quality of life in adolescent girls: A path analysis using a multi-mediation model. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 20 (2022).

Al-Fayez, G. A. & Ohaeri, J. U. Profile of subjective quality of life and its correlates in a nation-wide sample of high school students in an Arab setting using the WHOQOL-BREF. BMC Psychiatry 11 (2011).

Moutinho, I. L. D., Lucchetti, A. L. G., Ezequiel, O. da S. & Lucchetti, G. Mental health and quality of life of Brazilian medical students: Incidence, prevalence, and associated factors within two years of follow-up. Psychiatry Res. 274 , 306–312 (2019).

Jenkins, P. E., Ducker, I., Gooding, R., James, M. & Rutter-Eley, E. Anxiety and depression in a sample of UK college students: a study of prevalence, comorbidity, and quality of life. J. Am. Coll. Heal. 1–7 (2020).

Souza, I. M. D. M., Paro, H. B. M. da S., Morales, R. R., Pinto, R. de M. C. & Silva, C. H. M. da. Health-related quality of life and depressive symptoms in undergraduate nursing students. Rev. Lat. Am. Enfermagem 20 , 736–743 (2012).

Pagnin, D. & de Queiroz, V. Influence of burnout and sleep difficulties on the quality of life among medical students. Springerplus 4 , 1–7 (2015).

Pekmezovic, T., Popovic, A., Tepavcevic, D. K., Gazibara, T. & Paunic, M. Factors associated with health-related quality of life among belgrade university students. Qual. Life Res. 20 , 391–397 (2011).

Khalid, A., Qadir, F., Chan, S. W. Y. & Schwannauer, M. Adolescents’ mental health and well-being in developing countries: a cross-sectional survey from Pakistan. J. Ment. Health 28 , 389–396 (2019).

Ang, A. L., Wahab, S., Abd Rahman, F. N., Hazmi, H. & Md Yusoff, R. Depressive symptoms in adolescents in Kuching, Malaysia: Prevalence and associated factors. Pediatr. Int. 61 , 404–410 (2019).

Damaiyanti, M. & Rahmah Fitriani, D. The relation of educational level, academic achievement (GPA) and depression among public school adolescent. Indones. J. Nurs. Pract. 1 , 83–90 (2017).

Lim, G. Y. et al. Prevalence of depression in the community from 30 countries between 1994 and 2014 /692/699/476/1414 /692/499 article. Sci. Rep. 8 , 1–10 (2018).

Article ADS Google Scholar

Mojtabai, R., Olfson, M. & Han, B. National trends in the prevalence and treatment of depression in adolescents and young adults. Pediatrics 138 , e20161878 (2016).

Ng, Q. X., Lim, D. Y. & Chee, K. T. Reimagining the spectrum of affective disorders. Bipolar Disord. 22 , 638–639 (2020).

Parker, G., Gladstone, G. & Chee, K. T. Depression in the planet’s largest ethnic group: The Chinese. Am. J. Psychiatry 158 , 857–864 (2001).

Derdikman-Eiron, R. et al. Gender differences in subjective well-being, self-esteem and psychosocial functioning in adolescents with symptoms of anxiety and depression: Findings from the Nord-Trøndelag health study. Scand. J. Psychol. 52 , 261–267 (2011).

Zadow, C., Houghton, S., Hunter, S. C., Rosenberg, M. & Wood, L. Associations between positive mental wellbeing and depressive symptoms in Australian adolescents. Educ. Dev. Psychol. 34 , 95–105 (2017).

Solis, A. C. & Lotufo-Neto, F. Predictors of quality of life in brazilian medical students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brazil. J. Psychiatry 41 , 556–567 (2019).

Ng, Q. X. et al. Systematic review with meta-analysis: The association between post-traumatic stress disorder and irritable bowel syndrome. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 34 , 68–73 (2019).

Mahmoud, J. S. R., Staten, R. T., Hall, L. A. & Lennie, T. A. The relationship among young adult college students’ depression, anxiety, stress, demographics, life satisfaction, and coping styles. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 33 , 149–156 (2012).

Yüksel, A. & Bahadir-Yilmaz, E. Relationship between depression, anxiety, cognitive distortions, and psychological well-being among nursing students. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care 55 , 690–696 (2019).

Tempski, P. et al. Relationship among medical student resilience, educational environment and quality of life. PLoS ONE 10 , 1–13 (2015).

Tan, S. H., Tang, C., Ng, W. W. N., Ho, C. S. H. & Ho, R. C. M. Determining the quality of life of depressed patients in Singapore through a multiple mediation framework. Asian J. Psychiatr. 18 , 22–30 (2015).

Goulart, D. M. & González-Rey, F. Mental health care and educational actions: From institutional exclusion to subjective development. Eur. J. Psychother. Couns. 18 , 367–383 (2016).

Muros, J. J., Pérez, F. S., Ortega, F. Z., Sánchez, V. M. G. & Knox, E. The association between healthy lifestyle behaviors and health-related quality of life among adolescents. J. Pediatr. (Versão em Port.) 93 , 406–412 (2017).

Petrovič, F. & Murgaš, F. Description relationship between urban space and quality of urban life. A geographical approach. Land 10 , 1337 (2021).

Petrovič, F., Murgaš, F. & Králik, R. Happiness in Czechia during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sustainability 13 , 10826 (2021).

Puthran, R., Tam, W. W. & Ho, R. C. Prevalência de depressão entre estudantes de medicina : uma meta-análise. 456–468 (2016).

Shareef, M. A. et al. The interplay between academic performance and quality of life among preclinical students Career choice, professional education and development. BMC Med. Educ. 15 , 1–8 (2015).

Wang, C. et al. Anxiety, depression, and stress prevalence among college students during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Coll. Health https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2021.1960849 (2021).

Liyanage, S. et al. Prevalence of anxiety in university students during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19 , 62 (2021).

Zhang, Z. et al. Prevalence of depression and anxiety symptoms of high school students in shandong province during the COVID-19 epidemic. Front. Psychiatry 11 , 1–8 (2020).

Ahmed, M. Z. et al. Epidemic of COVID-19 in China and associated psychological problems. Asian J. Psychiatr. 51 , 102092 (2020).

Souza, A. S. R. et al. Factors associated with stress, anxiety, and depression during social distancing in Brazil. Rev. Saude Publica 55 , 1–15 (2021).

Ma, L. et al. Prevalence of mental health problems among children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 293 , 78–89 (2021).

Guessoum, S. B. et al. Adolescent psychiatric disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown. Psychiatry Res. 291 , 113264 (2020).

Nobari, H. et al. Effect of covid-19 on health-related quality of life in adolescents and children: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18 , 1–12 (2021).

Szczepańska, A. & Pietrzyka, K. The COVID-19 epidemic in Poland and its influence on the quality of life of university students (young adults) in the context of restricted access to public spaces. J. Public Health (Bangkok) 31 , 295–305 (2023).

Nisa, D. F. & Putri, N. K. How is the coronavirus outbreak affecting the daily lives of university students?. J. Kesehat. Lingkung. 12 , 137 (2020).

Maxim, L. D., Niebo, R. & Utell, M. J. Screening tests: A review with examples. Inhal. Toxicol. 26 , 811–828 (2014).

Malibary, H., Zagzoog, M. M., Banjari, M. A., Bamashmous, R. O. & Omer, A. R. Quality of Life (QoL) among medical students in Saudi Arabia: A study using the WHOQOL-BREF instrument. BMC Med. Educ. 19 , 1–6 (2019).

Kleszczewska, D., Szkutnik, A. M., Siedlecka, J. & Mazur, J. Physical activity, sedentary behaviours and duration of sleep as factors affecting the well-being of young people against the background of environmental moderators. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 16 , 915 (2019).

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Federal Institute of Education, Science and Technology of Goiano (IF Goiano) for funding this research, and the Child and Adolescent Health Research Group (GPSaCA).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Instituto Federal de Educação, Ciência e Tecnologia Goiano, GO-154, Km 03, Ceres, Goiás, 76300-000, Brazil

Michele da Silva Valadão Fernandes, Priscilla Rayanne e Silva Noll & Matias Noll

Graduate Program in Health Sciences, School of Medicine, Universidade Federal de Goiás, Goiânia, Brazil

Carolina Rodrigues Mendonça

Instituto Federal do Triângulo Mineiro, Uberaba, Minas Gerais, Brazil

Thays Martins Vital da Silva

Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil

Priscilla Rayanne e Silva Noll

Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo, Vitória, Espirito Santo, Brazil

Luiz Carlos de Abreu

Universidade Federal de Goiás, Goiânia, Brazil

Matias Noll

Rede Estadual e Municipal de Educação de São Luís de Montes Belos, Ceres, Goiás, Brazil

Michele da Silva Valadão Fernandes

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Conceptualization, M.d.S.V.F. and M.N.; methodology, M.d.S.V.F. and M.N.; software, M.d.S.V.F. and C. R. M..; formal analysis, M.d.S.V.F., C. R. M. and M.N.; investigation, M.d.S.V.F., C. R. M. and M.N.; resources, M.d.S.V.F., L. A. and M.N.; writing—original draft preparation, M.d.S.V.F.; writing—review and editing, M.d.S.V.F., C. R. M., T.M.V.d.S., P.R.e.S.N., and M.N.; visualization, M.d.S.V.F. and M.N.; supervision, M.N.; project administration, M.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Correspondence to Michele da Silva Valadão Fernandes or Matias Noll .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Supplementary information., rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Fernandes, M., Mendonça, C.R., da Silva, T.M.V. et al. Relationship between depression and quality of life among students: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep 13 , 6715 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-33584-3

Download citation

Received : 15 May 2022

Accepted : 15 April 2023

Published : 25 April 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-33584-3

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Quality of life among youth with misophonia: the role of internalizing symptoms and pessimism.

- Minjee Kook

- Catherine E. Rast

- Andrew G. Guzick

Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment (2024)

Cross-lagged analysis of relationship between self-deception, psychological capital and depression in normal university students

- Rozita Wahab

- Rafidah Aga Mohd Jaladin

Discover Psychology (2024)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

- Open access

- Published: 03 June 2010

Human depression: a new approach in quantitative psychiatry

- Massimo Cocchi 1 , 2 , 3 ,

- Lucio Tonello 1 , 3 &

- Mark M Rasenick 4

Annals of General Psychiatry volume 9 , Article number: 25 ( 2010 ) Cite this article

12k Accesses

12 Citations

6 Altmetric

Metrics details

The biomolecular approach to major depression disorder is explained by the different steps that involve cell membrane viscosity, Gsα protein and tubulin. For the first time it is hypothesised that a biomolecular pathway exists, moving from cell membrane viscosity through Gsα protein and Tubulin, which can condition the conscious state and is measurable by electroencephalogram study of the brain's γ wave synchrony.

Introduction

The need for a deep, radical turning point in the world of psychiatry is rapidly growing. Present diagnostic methods cannot continue to be considered acceptable because they are almost completely based on the psychiatrist's opinion, which does not have an objective diagnostic technology and thus has a very high error rate.

A debate is essential between the advocates of traditional diagnostic and therapeutic methods and advocates of emerging methods resulting from new discoveries. Major depressive disorder and other related and non-related psychiatric conditions are still characterised and defined by descriptive and non-biological criteria, but it is hoped that we can adequately characterise this and other psychiatric disorders with the addition of new quantitative approaches.

Human depression in the interpretation of an artificial neural network

Following the theory that a biomolecular involvement of the cell could be an expression of a psychiatric disorder, we have tried to understand and explain this phenomenon.

The intention was to study the platelet fatty acids composition in normal and depressed subjects [ 1 ], because of their similarity to neurons [ 2 – 10 ].

Membrane platelet fatty acids of subjects with a clinical diagnosis of major depression versus apparently normal subjects were assessed. The complexity of membrane dynamics has also suggested study by means of non-linear advanced analytical tools would be appropriate. In particular, it seemed more appropriate to use artificial neural networks: the self-organising map (SOM) Kohonen network [ 11 – 13 ]. This particular algorithm allows viewing of the result graphically, building a two-dimensional map that places the subjects in a continuous, not necessarily dichotomised way.

The values for fatty acids in the two populations were entered into the SOM, mixing normal and pathological subjects and hiding the information relating to their pathological condition. The SOM was then used to map the two populations using three specific fatty acids: palmitic acid (PA), linoleic acid (LA) and arachidonic acid (AA), which represent the majority of total membrane fatty acids, recognising as similar those belonging to the same population and then separating the normal cases from the pathological cases [ 1 ]. All the artificial neural networks (ANNs) tested gave essentially the same result. However, the SOM gave superior information by allowing the results to be described in a two-dimensional plane with potentially informative border areas. The central property of the SOM is that it forms a non-linear projection of a high-dimensional data manifold on a regular, low-dimensional (usually 2D) grid.

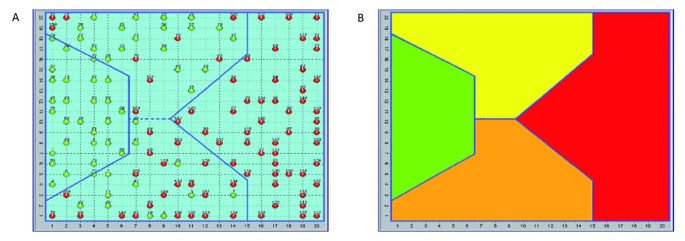

This experiment was performed outside of evidence-based medicine (EBM) rules. The direct task of finding biomarkers according to the EBM rules requires the elimination of selection bias, and in psychiatric illness the leads to the selection of a population that is often clinically unrealistic. The results are shown in Figure 1a, b .

Distribution of the human subjects (normal and depressive) over the self-organising map (SOM) (a), and SOM areas (b) . (a) The distribution of the 144 subjects studied, 60 apparently healthy (green) and 84 diagnosed as depressed (red) effected by the SOM allowed us to identify 4 areas: 2 specific ones (exclusively normal and exclusively pathological) and 2 mixed with different concentrations of pathological subjects and apparently normal subjects of the sample. The red subjects in the two intermediate areas (yellow and orange) have been interpreted as having a misleading diagnosis of major depression, as described in the literature [ 14 ]. (b) SOM areas. Green = normal, red = depressive, yellow = high density of normal subjects, orange = high density of pathological subjects.

The SOM has shown considerable correlation to the clinical diagnosis of major depression, and indeed, revealed the existence of differences within the same diagnosis. The literature shows that a diagnosis of major depression is very often misleading, and can be changed to a diagnosis of bipolar disorder [ 14 ].

Using the following equation (Equation 1), which relates each fatty acid percentage with the melting point and the molecular weight, we obtained a result that led us to understand that platelet membranes had different degrees of viscosity and/or unsaturation (B2 index).

Where A i = percentage of i -th fatty acid, mp = melting point, mw = molecular weight, mw i = molecular weight of i -th fatty acid, mp i = melting point of i -th fatty acid, and i :

1 = palmitic acid, C 16:0

2 = linoleic acid, C 18:2

3 = arachidonic acid, C 20:4

The result clearly showed that the platelet membranes of depressive subjects were characterised by a much higher degree of fatty acid unsaturation than normal subjects.

According to Donati et al. [ 15 ] rapid changes in membrane lipid composition or in the cytoskeleton could modify neuronal signalling. As this could have implications for a new understanding of some aspects of psychiatric disorders, a private meeting was organised in Bologna (Faculty of Veterinary Medicine) and in Treviso, University, October 2008) with some expert scientists in the field (Kary Mullis and Stuart Hameroff).

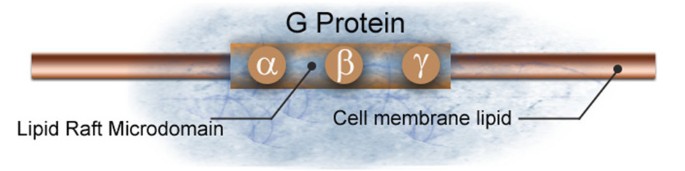

Three essential points constituted the crucial elements of the discussion at the meeting: (1) the viscosity of the platelet and neuronal membrane; (2) the protein Gsα; (3) the relationship between tubulin and consciousness.

With regard to the first point, Cocchi and Tonello observed that the platelet membrane was substantially differentiated from a chemical point of view with regard to the indexes of saturation between depressed and normal populations [ 1 ].

On the second point, the protein Gsα modifies its structure according to the degree of viscosity of the neuronal membrane, as seen in patients who commit suicide for psychiatric reasons in comparison to deaths from other causes [ 15 ].

With regard to the third point, Tubulin, because of its connection to Gsα and its position in the cellular cytoskeleton, determines those changes that have been assessed with quantum computation under conditions of wakefulness in comparison to the condition of anaesthesia [ 16 ].

Biomolecular depression hypothesis

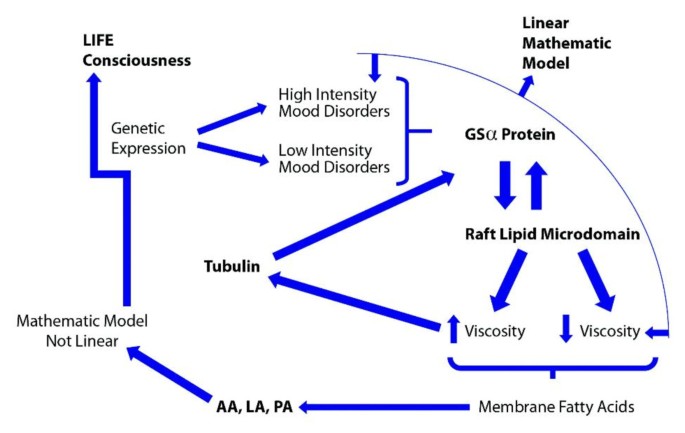

A very suggestive hypothesis was built, as summarised in Figure 2 .

Description of the biomolecular steps possibly involved in depressive disorder .

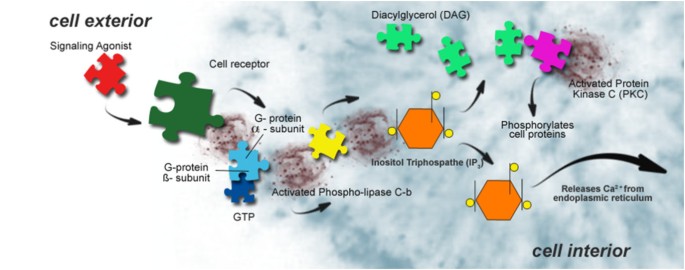

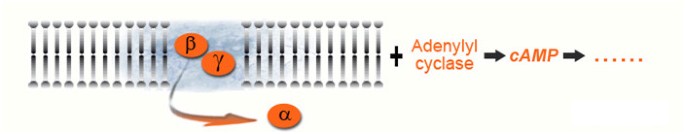

Figure 2 describes the molecular depression hypothesis formed according to the experimental findings of Cocchi et al. [ 1 ], Donati et al. [ 15 ], Hameroff and Penrose [ 16 , 17 ] and Hameroff [ 17 ]. Because of the possible similarity in behaviour of platelets and neurons, membrane viscosity may therefore modify the Gsα protein status. The Gsα protein is connected with tubulin. Tubulin, depending on local membrane lipid phase concentration, may serve as a positive or negative regulator of phosphatidylinositol bisphosphate (PIP2) hydrolysis, as G proteins do. Tubulin is known to form high-affinity complexes with certain G proteins. The formation of such complexes allows tubulin to activate Gα protein, which, in turn, can activate protein kinase C (PKC), and fosters a system whereby elements of the cytoskeleton can influence G-protein signalling. PKC activation (Figure 3 ) is preceded by a number of steps, originating from the binding of an extracellular ligand that activates G-protein on the cytosolic side of the plasma membrane [ 18 ].

Description of protein kinase C (PKC) activation .

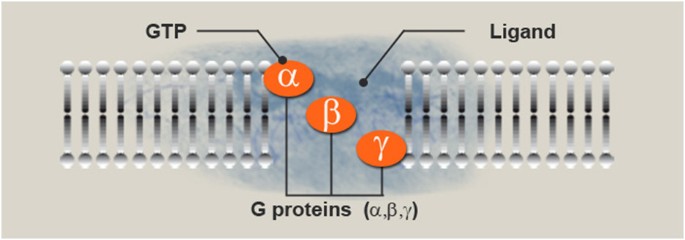

The G-protein, using guanosine triphosphate (GTP) as an energy source, then activates PKC via the PIP2 intermediate, the diacylglycerol/inositol triphosphate (DAG/IP3) complex [ 15 ]. The schematic biomolecular mechanism of the Gsα protein is described in Figure 4 .