- Posts for PhD students

- Visit LSE Careers’ website

- Visit CareerHub

Farah Chowdhury

June 15th, 2019, how to use your dissertation skills to market your employability.

2 comments | 15 shares

Estimated reading time: 10 minutes

Many of you will be doing your dissertation right now (or have done one already) and might be wondering how to make it work for your applications. Thankfully, your dissertation will give you a whole set of skills and assets that will be attractive to employers. Listed here are just a small selection of the qualities you can develop by doing a dissertation, and how they relate to working in the real world.

Research skills

One thing that everyone has to do for their dissertation is research. This is a very important skill to have in the working world. Good research skills mean that you know what is and isn’t relevant to a project, and that you know how to apply information effectively to meet your needs.

You should also apply your research skills when looking for a job. Employers look for people that are knowledgeable about the company and the industry, as this means you may have more innovative and informed ideas about how to move forward. This also shows a dedication to the company and industry, which is also very attractive to employers.

Problem solving

Problem solving can be a bit of a buzz term, but it’s so much more than that: it shows that you have initiative, you’re adaptable, and that you have critical thinking skills.

If you can show an employer an obstacle you came across during your dissertation and then demonstrate how you overcame that (and possibly what you’d do differently), then they will be able to see how you will react to issues that arise during your employment.

For instance, if you found your argument didn’t quite work and you had to reassess your methods, then that shows you know when to change your tactics and that you have the self-awareness to understand when you’re pursuing the wrong outcome.

Communication

Employers want to know that you can concisely communicate ideas and information, whether this is on paper or in person.

Writing a dissertation demonstrates that you can take a set of complex arguments and write them up in a way that is both understandable and convincing. This is something that will relate to all parts of your career, from report writing to persuading colleagues, employees, or managers of what the best course of action for the company is too.

Likewise, if you’ve done a dissertation you’ve probably discussed your ideas with your academic advisor, tutor, course mates, and others. If you can show you’ve taken advice from these people about your dissertation, then employers will know that you can be a team player and respect the opinions of others.

Specialist information

This may not be the case for everyone, but sometimes your dissertation topic will be on something that can be a starting point for your career and/or further study.

You can use your dissertation as a case study for your knowledge of the industry or work that you’re interested in pursuing after your course, and to show that you have a good sense of the kinds of issues that might arise when you’re in the job.

Numerical skills

A lot of companies request that you have numerical skills, so if you’ve dealt with large sets of data for your dissertation then you can unequivocally prove this.

Not only that, but if you’ve been using a software package like SPSS for your data analysis you can show that you also have strong computer skills and have data analysis experience. Don’t forget about programmes like Microsoft Excel too: if you know your way around a pivot table, make sure this is clear!

Calm under pressure

If you’ve managed to complete a large piece of work like a dissertation, then you can probably manage a company project. Completing your dissertation means that you can work under pressure and stay calm while managing multiple deadlines.

Whether or not you were in the library at 4am sobbing into your notes the day before it due is irrelevant: you completed a large project once, and so that shows you can absolutely do it again!

Project management

As mentioned briefly above, if you’ve managed completing a large piece of work like a dissertation, then you can manage a project at work. However this is more than just meeting deadlines and staying focused under pressure.

Project management is shorthand for a huge range of skills, including time management, working alone, team work, communication, and perseverance. If you can break down your project management skills into these individual abilities, and show how you have used them, then you will stand out to employers who will then know you know what they’re looking for.

Share this:

About the author

- Pingback: So you’ve handed in your dissertation…what next? | LSE Careers blog

- Pingback: How to market your MSc effectively to employers | LSE Careers blog

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

Related Posts

“Go for it and work hard” – entrepreneurship roundtable with LSE alumni

October 28th, 2014.

Student blog: Making the most of LSE Careers as an undergraduate student

August 18th, 2023.

Writing a CV that works – top tips for marketing yourself

January 27th, 2020.

Young Trustee: Zulum Elumogo

August 11th, 2021.

Bad Behavior has blocked 1115 access attempts in the last 7 days.

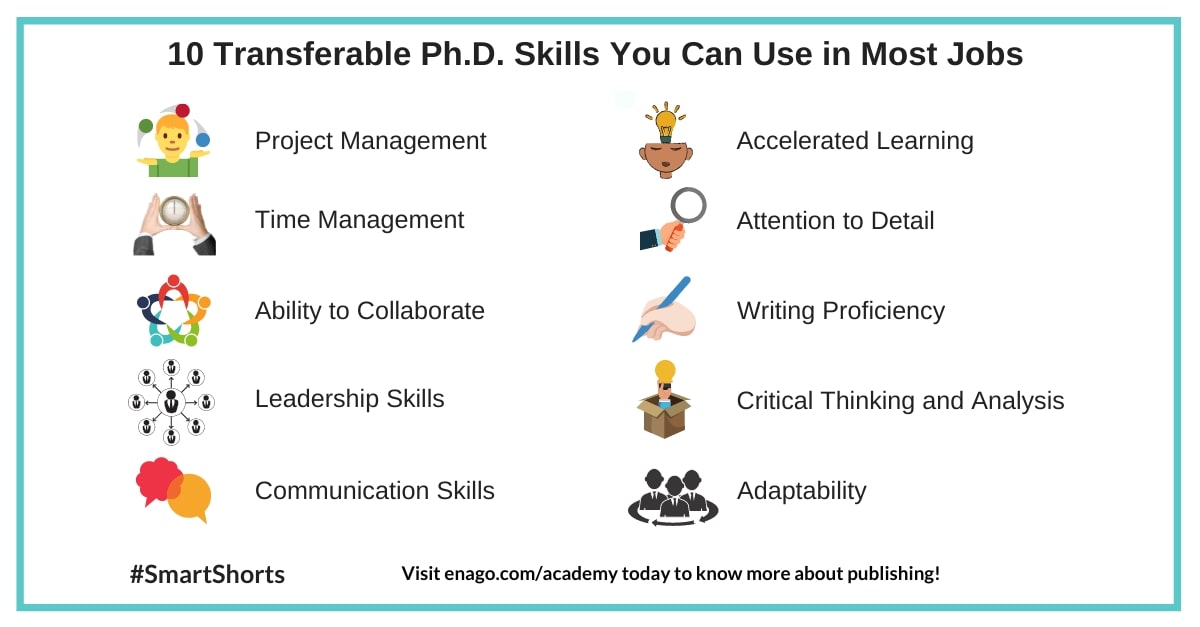

10 PhD Transferable Skills You Can Use in Most Jobs

“No one wants to hire PhDs because they are overqualified and too independent!”

This is one thing PhDs are tired of hearing. How can your PhD be a liability to your career? Rather, recruiters prefer PhD candidates over others not just for their qualification but for their PhD transferable skills.

Table of Contents

What are PhD Transferable Skills?

PhD Transferable skills are exactly what the name suggests! These are skills other than technical skills that you develop in your academic program. Furthermore, these skills are so versatile that they can be used everywhere, irrespective of the designation or field. Transferable skills are desirable because if you already have them, your employer will not have to train you on them. Consequently, you can make positive contributions in any career with these skills.

Which are the PhD Transferable Skills that You Must Develop?

Considering that a doctorate degree is the highest degree in most fields, the skills that are required to excel in the same are impeccable. Undoubtedly, researchers pursuing their Ph.Ds. or postdocs develop technical skills related to their research. However, what they also need to develop is a host of research transferable skills they can use as they progress in their careers.

Which are 10 PhD Transferable Skills You Can Use in Most Jobs?

With the surge of jobs for PhD in STEM, recruiters struggle to fill those positions with talented candidates. They are always in need of trained professionals who know how to create information from scratch, and not just recreate it in a tinkering manner.

While your work experience and education during PhD is an asset, you’d be surprised to find out that employers in most sectors pay close attention to your skill set. According to a recently published survey report by LinkedIn, 57% of respondents identified soft transferable skills as more important than hard skills (technical knowledge).

Here, we list 10 significant PhD transferable skills students can use in most jobs.

1. Project Management

The most apparent thought that comes to anyone’s mind while thinking about PhD is “project management” skills. A successful research experience goes hand-in-hand with a well-planned project. As simple as it may sound, the management skills of a PhD graduate are not confined to his/her project. It starts right from ideation of the research project to final submission, which results in an ultimate success of the project. Different stages of a PhD’s journey demands customized planning and organizing to ensure that deadlines are met and projects are completed efficiently and effectively. Furthermore, a PhD makes sure that all plans are duly incorporated. Employers seek candidates with PhD transferable skills as they want someone who can not only see a task through, but can visualize what needs to happen on a project from start to finish.

2. Accelerated Learning

As a doctor of philosophy, the ability to ascertain knowledge runs thick in the veins of a PhD researcher. An inquisitive mind and quick comprehension of technical things is interlinked to your accelerated learning ability. Moreover, being a PhD, you attend conferences and read papers to stay on top of the latest trends in your field. Consequently, PhD transferable skills ensure employers of your ability to understand technical procedures, protocols, and methodologies.

3. Time Management

Time waits for none! The key to a tension-free and smooth workflow is effective time management . While planning is important, defining your deadlines, setting realistic and achievable goals, and adhering to them takes you a long way! At a job, every moment spent on an unfocused or frivolous task, is a waste of money. Contradictorily, time management may not be viewed similarly in academia. However, as a PhD your motive has been to complete your program in time. This acts as a serious motivation to develop excellent time management skills.

4. Attention to Detail

One of the essential core skills of a PhD is paying attention to the details. To the best of your experience as a researcher, you are aware that mistakes can be missed in the bat of an eye. Therefore, it is a known fact that PhDs are one of the finest people to make sure that each project runs through a fine-tooth comb. As a result, employers can count on you for detail-oriented assignments that require critical assessment and corrections.

5. Ability to Collaborate

As stated earlier, PhDs are not new to working in groups to achieve common goals. Your significant contribution in research groups, as a researcher and author during your PhD program demonstrates your ability to collaborate . Employers seek candidates who are team players making positive contributions to the success of a group.

6. Writing Proficiency

Given the nature of modern technology, writing may not be a primary task of most job profiles. However, it sure is an essential element for academic and allied knowledge dissemination careers. In due course of pursuing a PhD, you come across countless reading material from authors all around the world. This subsequently stocks up your bank of vocabulary and enhances your writing skills for an unambiguous conveyance of messages and information.

7. Leadership Skills

Leadership skills aren’t only your ability to supervise and manage a team, but to take the lead on a project and get a team to follow through and achieve goals. As a PhD you’re the “lead” for your project. While it doesn’t necessarily involve leading other people, it still means being responsible for major decisions to accomplish targets. Additionally, it is common for PhD students to work in research groups and collaborate on shared projects. Nonetheless, they also demonstrate leadership while organizing conferences and seminars for their department or university. PhDs are also seen showing leadership skills while advising students and mentoring peers.

8. Critical Thinking and Analysis

As a PhD, it’s a given that you are able to analyze data and provide logical reasoning to it. Throughout your program, you collect data, analyze it, and draw conclusions. The ability of a PhD to critically examine everything and deliver logical reasoning behind it is not new to anyone. A PhD is well versed with 360-degree logical thinking without being biased. Employers seek these research transferable skill of a PhD to consider alternative solutions to a problem and suggest next steps for efficient functioning.

9. Communication Skills

This is the master of PhD transferable skills. Even if you decide to step into a career that is a 180-degree sweep from your PhD, you’d still need to communicate! Your ability to communicate efficiently is developed right from preparing for your PhD interview, presenting papers and posters at academic conferences, defending your thesis, etc. As verbal communication affects your ability to work with your peers, it is one of the most sought after research transferable skills by employers.

10. Adaptability

A PhD isn’t only about specialization. Rather, it’s about the ability to specialize. During your PhD you learn to tackle a new topic, solve it, and move on to the next problem. Almost all careers require employees to focus on specific topics and projects in detail to achieve a specific goal. Your ability of in-depth specialization in academic research project demonstrates adaptability and flexibility —quite literally!

So the next time you are asked, “What skills do you bring to this position?”, you certainly know how to answer that! Brush up your PhD transferable skills to help you make the right career switch. Remember that your PhD isn’t a liability after all. In fact, it’s an asset! Let us know how you acquired these valuable skills that are highly sought after by employers today.

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

- Reporting Research

Choosing the Right Analytical Approach: Thematic analysis vs. content analysis for data interpretation

In research, choosing the right approach to understand data is crucial for deriving meaningful insights.…

Comparing Cross Sectional and Longitudinal Studies: 5 steps for choosing the right approach

The process of choosing the right research design can put ourselves at the crossroads of…

- Career Corner

Unlocking the Power of Networking in Academic Conferences

Embarking on your first academic conference experience? Fear not, we got you covered! Academic conferences…

Research Recommendations – Guiding policy-makers for evidence-based decision making

Research recommendations play a crucial role in guiding scholars and researchers toward fruitful avenues of…

- AI in Academia

Disclosing the Use of Generative AI: Best practices for authors in manuscript preparation

The rapid proliferation of generative and other AI-based tools in research writing has ignited an…

Mentoring for Change: Creating an inclusive academic landscape through support…

Intersectionality in Academia: Dealing with diverse perspectives

Meritocracy and Diversity in Science: Increasing inclusivity in STEM education

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

As a researcher, what do you consider most when choosing an image manipulation detector?

At home, abroad, working, interning? Wherever you are this summer, contact OCS or make an appointment for a virtual advising session. We are available all summer!

- Undergraduates

- Ph.Ds & Postdocs

- Prospective Students & Guests

- What is a Community?

- Student Athletes

- First Generation and/or Low Income Students

- International Students

- LGBTQ Students

- Students of Color

- Students with Disabilities

- Student Veterans

- Exploring Careers

- Advertising, Marketing & PR

- Finance, Insurance & Real Estate

- General Management & Leadership Development Programs

- Law & Legal Services

- Startups, Entrepreneurship & Freelance Work

- Environment, Sustainability & Energy

- Media & Communications

- Policy & Think Tanks

- Engineering

- Healthcare, Biotech & Global Public Health

- Life & Physical Sciences

- Programming & Data Science

- Graduate School

- Health Professions

- Business School

- Meet with OCS

- Student Organizations Workshop Request

- OCS Podcast Series

- Office of Fellowships

- Navigating AI in the Job Search Process

- Cover Letters & Correspondence

- Job Market Insights

- Professional Conduct & Etiquette

- Professional Online Identity

- Interview Preparation

- Resource Database

- Yale Career Link

- Jobs, Internships & Other Experiences

- Gap Year & Short-Term Opportunities

- Planning an International Internship

- Funding Your Experience

- Career Fairs/Networking Events

- On-Campus Recruiting

- Job Offers & Salary Negotiation

- Informational Interviewing

- Peer Networking Lists

- Building Your LinkedIn Profile

- YC First Destinations

- YC Four-Year Out

- GSAS Program Statistics

- Statistics & Reports

- Contact OCS

- OCS Mission & Policies

- Additional Yale Career Offices

PhD Transferable Skills

- Share This: Share PhD Transferable Skills on Facebook Share PhD Transferable Skills on LinkedIn Share PhD Transferable Skills on X

While at Yale, seek out additional experiences that develop these skills. They will benefit your future career, whatever course it takes. Note that to employers, relevant experience does not have to be a paid job. It can be any experience that develops skills that are important to their work.

The resources below can help you identify your particular skill set. These skills are a key input into the professional narrative that you will employ in your resume, cover letter, and interviews.

- Exploring Your Skills , Inside HigherEd

- PhD Transferable Skills (courtesy of the University of Michigan)

- Transferable Skills and How to Talk About Them , from Connected Academics (MLA)

- Making the most of your transferable skills , from CellPress

Looking for ways to enhance your transferable skill set while at Yale? Below is a list that can get you started.

- Consider teaching a class or becoming a research or teaching assistant.

- Digital Humanities Lab

- Yale Center for Science and Social Science Information (CSSSI)

- Yale Center for Collaborative Arts and Media (CCAM)

- Center for Engineering Innovation and Design

- Mentor students

- Manage lab supplies and equipment

- Take a leadership role in a GSAS student organization

- GSAS students are invited to become a McDougal Fellow or GPE Fellow

- Seek out an internship or part-time opportunity either on or off campus

- Perform volunteer work

- Hone your writing skills

- Work on a consulting project through the Yale Graduate Consulting Club or Tsai CITY

- Improve your Excel skills, learn Python or master basic accounting by taking an online course! Check out the offerings on LinkedIn Learning (free to Yale students, staff and faculty through this portal

Office of Career Strategy

Visiting yale.

The 7 Essential Transferable Skills All PhDs Have

During your PhD, you’re not just learning about your research topic. You’re also learning core skills that apply to jobs both in and out of academia. Most institutions don’t teach you to articulate these transferable skills in a way that aligns with how they’re described in the business world. Knowing your skills increases your value as a candidate.

Written Communication

It takes practice to become a good writer. Fortunately, as PhD student you have years of practice writing papers, conference abstracts, journal manuscripts, and of course your dissertation. The feedback you receive from your supervisor and peer reviewers will help improve your communication skills.

Research skills are valuable even in many fields outside of academia. As a trained researcher, you are able to determine the best approach to a question, find relevant data, design a way to analyze it, understand a large amount of data, and then synthesize your findings. You even know how to use research to persuade others and defend your conclusions.

Public Speaking

Strong oral communications skills are always valued, and PhD students get more public speaking opportunities than most. Through conference talks, poster presentations, and teaching, you will learn to feel comfortable in front of a larger audience, engage them, and present complex ideas in a straightforward way. Winning a teaching award or being recognized as the best speaker at a conference is a concrete way to prove your public speaking skills.

Project Management

Even if you’re not working as a project manager, every job requires some degree of project management. Fortunately, a PhD is an exercise in project management. Finishing your dissertation requires you to design a project, make a realistic timeline, overcome setbacks, and manage stakeholders. During this time, you will also have to manage long-term projects at the same time as short-term goals which requires strong organizational skills.

Mentoring and teaching are the two main way PhD student can learn leadership and management skills. As a teacher or mentor, you have to figure out how to motivate someone and help them accomplish a goal. You also get experience evaluating someone’s performance (grading) and giving constructive feedback.

Critical Thinking

Every PhD student learns critical thinking skills whether they realize it or not. You are trained to approach problems systematically, see the links between ideas, evaluate arguments, and analyze information to come up with your own conclusions. Any industry can benefit from someone who knows “how to think”.

Collaboration

Very few jobs require you to work completely independently, and academia isn’t one of them. Your dissertation is a solo project, but on a day to day basis you work with other people on your experiments or preparing a journal manuscript. Doing these tasks successfully requires knowing how to divide up a task, get along with others, communicate effectively, and resolve conflict.

Discover related jobs

Discover similar employers

Accelerate your academic career

The Nine Biggest Interview Mistakes

In order to guarantee you make a good impression, here are the nine bigg...

PhD, Postdoc, and Professor Salaries in the Netherlands

Interested in working in the Netherlands? Here's how much PhD students, ...

Don’t Fall Prey to Predatory Journals

These journals just want your money.

How to Write a PhD Elevator Pitch

How many times have you been asked, “What do you research?” only to draw...

The DOs and DON’Ts of Letters of Recommendation

To ensure you get strong letters of recommendation, follow these simple ...

Overcoming Impostor Syndrome

Impostor syndrome is a nagging feeling of self-doubt and unworthiness th...

Jobs by field

- Electrical Engineering 167

- Machine Learning 155

- Programming Languages 146

- Artificial Intelligence 142

- Molecular Biology 128

- Mechanical Engineering 128

- Cell Biology 117

- Materials Engineering 107

- Electronics 106

- Materials Chemistry 103

Jobs by type

- Postdoc 348

- Assistant / Associate Professor 139

- Researcher 123

- Professor 107

- Research assistant 97

- Engineer 81

- Lecturer / Senior Lecturer 66

- Management / Leadership 49

- Tenure Track 37

Jobs by country

- Belgium 308

- Netherlands 152

- Switzerland 116

- Morocco 116

- Luxembourg 60

- United Kingdom 48

Jobs by employer

- KU Leuven 118

- Mohammed VI Polytechnic Unive... 116

- Ghent University 76

- KTH Royal Institute of Techno... 65

- ETH Zürich 64

- University of Luxembourg 59

- University of Twente 48

- Eindhoven University of Techn... 41

- University of Antwerp 30

This website uses cookies

Graduate School

- Request Information

- Transferable Skills Checklist

Assess Your Transferable Skills

To identify academic and professional goals in your Individual Development Plan , you must first assess your skills.

Why do we call them "transferable" skills?

- They are skills that realistically reflect your strengths, abilities, and gaps no matter your field of study.

- They correlate with competencies your future employers are looking for on a CV and/or resume.

- They are integral to every phase of your academic and professional development.

Listen to the experts

Featuring Sharolyn Kawakami-Shulz, PhD and Jenna Hicks PhD ( Medical School Office of Professional Development ), and doctoral candidate Chelsea Cervantes de Blois. Watch video here if you can't access YouTube.

After this video, you'll remember:

- Transferable Skills are applicable across a wide variety of sectors, careers, and position types.

- As a graduate student, you are already developing transferable skills; it should be your goal to apply them outside your current environment.

- On resume or in an interview, It is important to provide relevant and specific examples that demonstrate your skills.

- Speak the cultural language of the person or field in which you're communicating.

- Add transferable skills goals to your Individual Development Plan (IDP) .

+ Communication

Communication as a broad objective.

Skillfully express, transmit, and interpret knowledge and ideas.

Specific Skills

- Communicate across cultural backgrounds

- Communicate to a wide audience

- Communicate to a non-specialist audience

- Speak effectively

- Write concisely

- Listen attentively

- Express ideas

- Facilitate group discussion

- Provide appropriate feedback

- Perceive nonverbal messages

- Report information

- Describe feelings

+ Research & Planning

Research & planning as a broad objective.

Successfully search for specific knowledge and conceptualize future needs and solutions.

- Forecast, predict

- Create ideas

- Identify problems

- Imagine alternatives

- Identify resources

- Gather information

- Solve problems

- Extract information

- Define needs

- Develop evaluation strategies

+ Human Relations

Human relations as a broad objective.

Use interpersonal skills to resolve conflict, relate to, and help people.

- Develop rapport

- Be sensitive

- Convey feelings

- Provide support for others

- Share credit

- Delegate with respect

- Represent others

- Perceive feelings, situations

+ Management & Leadership

Management & leadership as a broad objective.

Supervise, direct, and guide individuals and groups to complete tasks and fulfill goals.

- Initiate new ideas

- Handle details

- Coordinate tasks

- Manage groups

- Delegate responsibility

- Promote change

- Sell ideas or products

- Make decisions with others

- Manage conflict

+ Work Survival

Work survival as a broad objective.

Use day-to-day skills to promote productivity and work satisfaction.

- Implement decisions

- Enforce policies

- Be punctual

- Manage time

- Attend to detail

- Enlist help

- Accept responsibility

- Set and meet deadlines

- Make decisions

Get Started!

Download a Transferable Skills Checklist

This Transferable Skills Checklist was first developed by the University of Minnesota Duluth's Career & Internship Services .

- About the Grad School

- Staff Directory

- Office Locations

- Our Campuses

- Twin Cities

- Mission & Values

- Strategic Plan

- Policies & Governance

- Graduate School Advisory Board

- Academic Freedom & Responsibility

- Academic & Career Support

- GEAR 1 Resource Hub

- GEAR+ Resource Hub

- Ask an Expert

- Graduate School Essentials for Humanities and Social Sciences PhDs

- Graduate School Essentials for STEM PhDs

- Grad InterCom

- First Gen Connect

- Advising & Mentoring

- Individual Development Plan (IDP)

- Three-Minute Thesis

- Application Instructions

- Application Fees

- Big 10 Academic Alliance Fee Waiver Program

- Application Status

- Official Transcripts & Credentials

- Unofficial Transcripts & Credentials

- Recommendation Letters

- International Student Resources

- Admissions Guide

- Change or Add a Degree Objective

- Readmission

- Explore Grad Programs

- Preparing for Graduate School

- Program Statistics

- Recruiting Calendar

- Funding Opportunities

- Prospective & Incoming Students

- Diversity of Views & Experience Fellowship (DOVE)

- National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship

- Current Students

- Banting Postdoctoral Fellowship Program

- Distinguished Master's Thesis Competition

- Diversity Predoctoral Teaching Fellowships

- Doctoral Dissertation Fellowship

- Excellence in Teaching Award

- Fulbright U.S. Student Program

- Graduate SEED Awards

- Harold Leonard Memorial Fellowship in Film Study

- Interdisciplinary Doctoral Fellowship

- Judd Travel Grants

- Louise T. Dosdall Endowed Fellowship

- Mistletoe Fellowship

- Research Travel Grants

- Smithsonian Institute Fellowship

- Torske Klubben Fellowship

- Program Requests & Nominations

- Bridging Funds Program

- Best Dissertation Program

- Co-Sponsorship Grants Program

- Google Ph.D. Fellowship

- National Science Foundation Research Traineeship

- National Science Foundation Innovations in Graduate Education Program

- Training Grant Matching Funds

- Fellowship Dates & Deadlines

- Information for Staff & Faculty

- About Graduate Diversity

- Diverse Student Organizations

- McNair Scholars Resources

- About the Community of Scholars Program

- Graduate Recruitment Ambassadors Program

- Community of Scholars Program Writing Initiative

- Faculty & Staff Resources

- Diversity Recruitment Toolkit

- Summer Institute

- Diversity Office Staff

- What's Happening

- E-Publications

- Submit Content

- News Overview

- Events Overview

Jump to navigation

Search form

The Graduate School

- Faculty/Staff Resources

- Programs of Study Browse the list of MSU Colleges, Departments, and Programs

- Graduate Degree List Graduate degrees offered by Michigan State University

- Research Integrity Guidelines that recognize the rights and responsibilities of researchers

- Online Programs Find all relevant pre-application information for all of MSU’s online and hybrid degree and certificate programs

- Graduate Specializations A subdivision of a major for specialized study which is indicated after the major on official transcripts

- Graduate Certificates Non-degree-granting programs to expand student knowledge and understanding about a key topic

- Interdisciplinary Graduate Study Curricular and co-curricular opportunities for advanced study that crosses disciplinary boundaries

- Theses and Dissertations Doctoral and Plan A document submission process

- Policies and Procedures important documents relating to graduate students, mentoring, research, and teaching

- Academic Programs Catalog Listing of academic programs, policies and related information

- Traveling Scholar Doctoral students pursue studies at other BTAA institutions

- Apply Now Graduate Departments review applicants based on their criteria and recommends admission to the Office of Admissions

- International Applicants Application information specific to international students

- PhD Public Data Ph.D. Program Admissions, Enrollments, Completions, Time to Degree, and Placement Data

- Costs of Graduate School Tools to estimate costs involved with graduate education

- Recruitment Awards Opportunities for departments to utilize recruitment funding

- Readmission When enrollment is interrupted for three or more consecutive terms

- Assistantships More than 3,000 assistantships are available to qualified graduate students

- Fellowships Financial support to pursue graduate studies

- Research Support Find funding for your research

- Travel Funding Find funding to travel and present your research

- External Funding Find funding outside of MSU sources

- Workshops/Events Find opportunities provided by The Graduate School and others

- Research Opportunities and programs for Research at MSU

- Career Development Programs to help you get the career you want

- Graduate Educator Advancement and Teaching Resources, workshops, and development opportunities to advance your preparation in teaching

- Cohort Fellowship Programs Spartans are stronger together!

- The Edward A. Bouchet Graduate Honor Society (BGHS) A national network society for students who have traditionally been underrepresented

- Summer Research Opportunities Program (SROP) A gateway to graduate education at Big Ten Academic Alliance universities

- Alliances for Graduate Education and the Professoriate (AGEP) A community that supports retention, and graduation of underrepresented doctoral students

- Recruitment and Outreach Ongoing outreach activities by The Graduate School

- Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Funding Funding resources to recruit diverse students

- Graduate Student Organizations MSU has over 900 registered student organizations

- Grad School Office of Well-Being Collaborates with graduate students in their pursuit of their advanced degree and a well-balanced life

- Housing and Living in MI MSU has an on and off-campus housing site to help find the perfect place to stay

- Mental Health Support MSU has several offices and systems to provide students with the mental health support that they need

- Spouse and Family Resources MSU recognizes that students with families have responsibilities that present challenges unique to this population

- Health Insurance Health insurance info for graduate student assistants and students in general at MSU

- Safety and Security MSU is committed to cultivating a safe and inclusive campus community characterized by a culture of safety and respect

- Why Mentoring Matters To Promote Inclusive Excellence in Graduate Education at MSU

- Guidelines Guidelines and tools intended to foster faculty-graduate student relationships

- Toolkit A set of resources for support units, faculty and graduate students

- Workshops Workshops covering important topics related to mentor professional development

- About the Graduate School We support graduate students in every program at MSU

- Strategic Plan Our Vision, Values, Mission, and Goals

- Social Media Connect with the Graduate School!

- History Advancing Graduate Education at MSU for over 25 years

- Staff Directory

- Driving Directions

PhD Transferable Skills

Translating your skills and experiences.

Transferable skills are skills you acquire or learn in one setting that can be applied or translated to new and different settings, environments, and activities. Doctoral students often fall into the trap of seeing their skills as applicable in only one setting, thus do not recognize that they are qualified for a wide variety of career paths. Don’t let this happen to you! In the table below you will find a list of skills most sought after by employers. In the final column of the table are examples of activities that demonstrate these essential skills. For several of the skills you can also take online assessments to identify which areas you still need to develop.

ESSENTIAL SKILLS: Adaptability , Analytic skills , Balance & resilience , Communication skills ( oral and written ), Conflict resolution/negotiation , Cultural/Intercultural , Discipline-specific skills , Ethics & Integrity , Follow-through/Ability to get things done , Fundraising , Independent (self-starter), Intelligence , Inter-/Multi- disciplinary , Interpersonal skills , Leadership (program) , Leadership (personnel/management) , Networking & collaboration , Organization , Outreach , Project management , Research , Self-direction/Entrepreneurial skills , Supervision , Technical skills (information technology), Work ethic

Essential Skills and Competencies for Graduate Students 1 :

1 Contents of table are adapted from Blickley, et al. (2012). “Graduate Student’s Guide to Necessary Skills for Nonacademic Conservation Careers.” Conservation Biology, 27:1. 2 Winterton, Delamare - Le Deist, and Stringfellow (2006). “Typology of knowledge, skills and competences: clarification of the concept and prototype.”

Additional resources on transferable skills:

- Plan Your Work & Work Your Plan [PDF]

- Graduate Student Skills (UIUC) [PDF]

- Call us: (517) 353-3220

- Contact Information

- Privacy Statement

- Site Accessibility

- Call MSU: (517) 355-1855

- Visit: msu.edu

- MSU is an affirmative-action, equal-opportunity employer.

- Notice of Nondiscrimination

- Spartans Will.

- © Michigan State University

- Public Lectures

- Faculty & Staff Site >>

Advice Topic: Transferable Skills

Thinking about your own path and preparation.

In a typical year, our summer schedules often allow us some space to step back, reflect, and focus on our own professional development. We hope that as we continue to respond to and slowly recover from the current pandemic, you will find a little time to focus on yourself as you prepare for the future. While these are admittedly uncertain times, it’s clear that now more than ever, the world needs well-educated, reasoned and experienced thinkers and innovators to help guide us through the recovery and into the future – this sounds like a description of UW postdocs!

In the past, we’ve shared advice on pursuing your passion projects , identifying your unique skills , and crafting documents for a successful job application . Here, we’d like to share two exceptional resources which allow you to both explore and enhance your skills and professional development: LinkedIn Learning and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Office of Intramural Training & Education (OITE).

LinkedIn Learning : The UW Career and Internship Center has purchased a license for full access to LinkedIn Learning . LinkedIn Learning is a collection of online videos to help you enhance and develop skills. Importantly, everyone with a UW NetID can access the resources. Spend some time exploring the site to get advice for your next career step, including:

- Writing a Resume , by Stacey Gordon;

- Informational Interviewing , by Barbara Bruno;

- Tips for Working Remotely , by Todd Dewett.

NIH OITE : The NIH OITE has responded to COVID-19 by making much of their internal professional development activities open to the public. While some admittedly have a scientific focus, many workshops on wellness and career and professional development are broadly applicable to the academic community (and beyond). Feel free to register (for free) for one of their upcoming workshops. We were particularly impressed with the following seminars:

- Essential Leadership Skills for Scientists , by Sharon Milgram, PhD;

- Strategies and Tools for Dealing with Stress During the Coronavirus Pandemic , by Laurie Chaikind McNulty;

- CVs, Resumes, and Cover Letters – Essential Job Search Documents, by Amanda Langer;

- Industry Careers – Overview and Job Packages , by Brad Fackler.

As a postdoc, it is imperative that you carve out some time to focus on YOU: assess what skills you have already developed and focus on how best to promote them. Equally as important, take the time to determine which skills and experiences you still need to develop as you prepare for your next career step. We encourage you to explore both LinkedIn Learning and the NIH OITE resources in your own time. And as always, we, the UW Office of Postdoctoral Affairs (OPA) , continue to be available for consultation and support as you navigate these difficult times.

Career Advice for Beyond the End of The Road

If the path before you is clear, you’re probably on someone else’s. – Joseph Campbell

Dr. Keith Micoli visited UW from NYU where he directs the postdoc office and has worked for a decade to support postdoc professional development. Dr. Micoli shared advice with UW postdocs at a workshop on October 16, and we share highlights with you here. For anyone who has done any kind of endurance activity, you will recognize a theme within these tips, drawn from Dr. Micoli’s own science training career and long-distance hiking activities:

Lesson 1 – Commit to Your Goal

- Knowing your goals will help you get through the inevitable tough moments, when you want to give up. You can’t hike 130 miles all at one shot.

- When something’s obviously not working, try something else.

- If you don’t know your goal, it’s a lot harder to accomplish anything.

Lesson 2 – Know the Difference Between Need and Want

- Rather than imagine what your faculty advisor is thinking about your path, talk about it ; you may be surprised!

- Set a date that you are NOT going to be a postdoc anymore; start working on your end goals NOW.

- When identifying where you want to go next, think not just about the position or job title, but also your values and how they fit the organization’s culture . myIDP and Doug’s Guides can give you some insights to explore further.

Lesson 3 – Know What Success Will Require of You

- What does it take to be a successful tenure-track faculty member? What does success look like in an alternative career?

- Are you willing to pay the price to pursue a certain career ? If you are not, you shouldn’t be doing it.

- Use your postdoc time to develop your many transferable skills , such as writing, teaching, counseling, organization, situation analysis, independence, meeting deadlines, negotiations, enlisting help, communication skills, course development, setting goals, supervising, coordinate, editing, research design, listening, networking , time management, selling ideas, resourcefulness, attention to details, collaborating, giving feedback, data analysis, presentations, take risks, budgeting, decision-making, artistic/creative, conflict management delegating, facilitating discussion, interpersonal skills, prioritizing, giving feedback…and more.

Lesson 4 – Do Your Best with What You Have

- Focus on things and places where you can have an impact, not on the things you can’t do.

- Visualize the completion of a goal, and then go backwards to plan for a timeline and achievable sub-goals.

- Sometimes you need to put in more resources to finish on time; sometimes you need to extend the deadline and to be realistic.

Lesson 5 – Be Realistic and Opportunistic

- Why is your goal important, and why hasn’t it already been achieved?

- What is the most direct way to achieve it?

- What resources do you have, and what resources do you need?

Lesson 6 – Never Give Up

- You don’t have the benefit of knowing where the finishing line is. Just keep going and never give up.

Graduating soon, and what next?

“I am a fifth-year doctoral student and will be graduating soon. I’m at the point in my graduate education where I am thinking about possible careers. What are some simple steps I can take to start my career planning?” –Anonymous

Lucky you, grad student, you get two answers to your question! One is from Catherine Basl, career counselor with Career & Internship Services. Catherine manages the center’s programming for graduate students. Another is from the Core Programs team, who support personal and professional development of grad students at the UW. You know what they say, two heads are better than one!

Catherine Basl, career counselor, Career & Internship Services:

Leverage your research skills for career planning! Aim for a mix of independent reading about options and connecting with professionals in coffee chats or at events.

A few ideas for getting started:

- Talk to one alum of your graduate program who works outside of academia in an area of possible interest. Graduate Program Advisers could be a good resource for finding alumni.

- Attend an event on campus ( Core Programs and the Career & Internship Center host many) that is focused on employer connections or exploring options.

- Reflect on your time here at UW. Consider all of the roles you have held as a graduate student (TA, research assistant, mentor, tutor, lab manager, writer, coder, etc.). Looking at each role, what were the tasks and activities you enjoyed most? Least? See if patterns emerge across roles. For an example of this activity, see pages 8-10 in the Career Guide .

- Paula Di Rita Wishart’s article on Career Callings also provides some great activities for reflecting on your graduate school experience and next steps.

- LinkedIn’s Alumni tool shows you where actual UW alumni work and you can sort by location, employer, and field of study to see possible career paths.

Some notes:

- Looking at job postings when you aren’t sure what you want to do can be overwhelming. Job boards become much more navigable when you have established criteria for what you want in a position. The same goes for large career fairs.

- Gather multiple data points. That means talking to more than one person, reading about career options on more than one website, and testing out the information you hear.

- Realize career planning is like all research projects—sometimes things fall into place quickly and sometimes you encounter roadblocks along the way. If you feel stuck or would like someone to brainstorm with, consider booking an appointment with a career counselor and checking in with mentors.

A few more resources for exploring:

- Carpe Careers series on Inside Higher Education

- Science Magazine (for STEM PhDs)

- ImaginePhD (for humanities, social science PhDs, launching in October!)

Core Programs Team:

Dear UW Grad Student,

Thank you for reaching out! This is a great question, and one we hear frequently from graduate students who are further along in their degree programs and thinking through different career paths. Whether you are thinking about working in industry, non-profits, government, or academia, there are several resources that can help you do intentional career planning (many of which we’ve learned through collaborations with partners at the Career & Internship Center).

First step: do some self-assessment work. Where are you with your skills, strengths, interests, passions? Then, use a planning tool like an Individual Development Plan (link) to start to map out possible goals and steps you can take toward them in the next few months. You can also utilize this helpful career planning guide from the Career & Internship Center that provides several clear, proactive steps you can take towards finding that job you’re passionate about.

To explore and open your possibilities, do LinkedIn searches for professionals with jobs you’re interested in learning more about and set up informational interviews to hear more about their unique career trajectories.

Explore different career options within academia and/or job sectors outside of academia with the amazing resources on the Career Center website.

We totally get that you are 100% focused on your dissertation work and graduation – it’s a lot! And, we know that setting aside 1-2 hours per week (starting right now) to explore, research, draft, attend something that helps you refine your career search will really help you identify career options and opportunities for your next steps. It’s worth it – give it a try!

Core Programs Team #UWGradSuccess

Translating Your Postdoc Experience into Practice

An academic journey is an interesting thing. After focusing on developing specialized knowledge in a field during your PhD and then digging deeper during your postdoc, it is understandable to wonder how you might use your specific expertise in different settings – whether inside or outside of academia.

A recent panel of Ph.D.s working in industry highlighted the importance of translating your doctoral and postdoc experience into broader terms. Taking an inventory of your skills, capabilities, and strengths can help you gain confidence as you begin to imagine you do have something remarkable to offer to a future employer or to leverage for success in your career.

Skills learned during graduate school and a postdoc fellowship have set you up to be a competitive applicant for most industry and start up jobs, in addition to the traditional academic track. By the completion of your training, you are highly intelligent, with an ability to learn and teach yourself “what you don’t know.” You are adept at gathering all the available information and making a good decision regarding what it means and what’s next. You have developed great analytical and logic-minded skills, which you can apply to move an issue, experiment or conversation forward. All it takes is stepping back, and reframing your experiences for a different audience.

Need some ideas about how your graduate and postdoc experiences have prepared you for a rewarding career inside or outside of academia? Check out this list from Peter Fiske’s keynote at the National Postdoc Association meeting 2017 (#NPA2017) to get you started:

- Ability to function in a variety of environments and roles

- Teaching skills; conceptualizing, explaining

- Counseling, interview skills

- Public speaking experience

- Ability to support a position/viewpoint with argumentation and logic

- Ability to conceive and design complex studies and projects

- Ability to implement and manage all phases of complex research projects and to follow them through to completion

- Knowledge of the scientific method to organize and test ideas

- Ability to organize and analyze data, to understand statistics and to generalize from data

- Ability to combine, integrate information from disparate sources

- Ability to evaluate critically

- Ability to investigate, using many different research methodologies

- Ability to problem-solve

- Ability to do advocacy work

- Ability to acknowledge many differing views of reality

- Ability to suspend judgment, to work with ambiguity

- Ability to make the best use of informed hunches

As you develop your own inventory, keep in mind that similar skills or capacities may be called different things in different sectors or fields. Do your research when you are targeting a job prospect and develop tailored versions of your CV or resume and cover letters to reflect the field specific terms. You are prepared – it just takes a little translation to help others see it easily. We invite you to budget an hour or so a week to explore the references below for more tools and ideas.

- Peter Fiske, 2015 at UC – Berkeley – Put Your PhD to Work: Practical Career Advice for Grad students and Postdocs

- Try taking a self-assessment with these quick activities: Dependable Career Strengths Exercises , UW Career & Internship Center

- Connect with other events, job listings, and online resources: Beyond Academia: Jobs and Internships , UW Career & Internship Center

- Identifying Skills , Graduate School of Arts & Sciences Career Services at Brandeis University

- PhD Transferable Skills , Career Center at University of Michigan.

Beyond “Plan B”: Crafting Your Career Journey

With today’s careers, it is more common than ever before to change directions multiple times in your life. This can happen in the course of a graduate program where perhaps the career you came looking for now looks different to you as your experiences have grown. We have an on-going theme in Core Programs of exploring diverse career trajectories. Below, we emphasize a few lessons shared by Philosophy alums at a recent panel, who are working in very diverse sectors. * Whether or not you are in a Humanities, Social Sciences, or a STEM field, these insights may be of use to you:

Beyond Hoops . We know there are many obligations and milestones to completing a graduate program. Rather than (only) thinking of these requirements as hoops to jump through, take some time to reflect upon the career skills you will gain from them over time— transferable career skills you can utilize for many jobs inside and outside of academia. For example, even when it’s not apparent to you at first, one skill set you develop when completing a thesis or dissertation are project management skills . Skills under project management can include, organization (outlining and prioritizing tasks that need to be completed), time management (setting up and meeting deadlines that are realistic), synthesizing complex ideas and details succinctly (writing up your project), and communication (meeting with advisors to state, clarify, and/or revisit your goals and expectations).

Beyond Job Titles. Instead of focusing solely on job titles during your job search, consider the kind of work you want to do and the kind of setting you would like to work within. What strengths do you have, and where are those best expressed? Recruiting expert Christian Lépolard offers these guiding questions to help you think expansively about your job search, “What is your ultimate career goal, inside and outside of your current organization? What hard skills (practical and theoretical), knowledge, and soft skills do you need to possess in order to get there? What skills do you already have and which ones do you need to acquire? What skills will this next role bring you?” Read more from Lépolard’s article . We would also add, what kinds of tasks and projects fuel your passions? What contribution do you want to make? How do you prefer to spend your time? Reflecting on these questions can help you find a range of ways you might be able to do your best work, rather than limiting yourself to certain job titles.

Beyond a “Career Path.” If we shift our thinking away from the idea of a “career path” (often imagined as linear) towards the notion of a career journey, then we open ourselves up to change, flexibility, and opportunity. Sometimes you just need to get your foot in the door at an organization or institution. Start out with a short-term internship (or in other instances, see if there are volunteer positions), as this experience will help you determine if you will enjoy working there and if the work and the workplace culture allow you to thrive. The right kind of entry-level position can open more doors quickly once you shine. It may not be a straight shot through to your dream job, but you increase your professional networks and get to showcase your talents along the way! Also, think broadly about a range of jobs that match your technical and transferable skills. Career strengths assessments such as this free one can help you do just that.

Spring can be a job search season for you, or perhaps a chance to line up more growth opportunities once summer arrives. It can also be a time to consider making a 1-1 appointment with a UW career advisor who can help give you feedback on your resume or CV. We are cheering for you – let us know how it is going!

Kelly, Jaye, and Ziyan

*Acknowledgements to panelists Summer Archarya, Dustyn Addington, Karen Emmerman, and Ann Owens from the Philosophy Branches Out event. This event was held on February 28, 2017 at UW Seattle and was co-sponsored by the UW Philosophy Department, the Simpson Center for the Humanities, and Core Programs in the Graduate School.

Exploring Career Paths: Strategic Steps Postdocs Can Take

In late May 2016, we have had the opportunity to hear from some exceptional speakers on campus who offered their perspective and insights to postdocs regarding exploration and preparation for careers that will be the best fit for YOU. We excerpted out the following top tips shared during these workshops from guests Kelly Sullivan of the Pacific Northwest National Labs, Linette Demers from Life Science Washington, Matt O’Donnell, Professor and Dean Emeritus in Engineering, Sumit Basu and Hrvoje Benko from Microsoft Research.

- Prepare : “Career planning isn’t so much about planning. But it is about preparing.” Having a clear roadmap won’t always help you, as it may limit you to opportunities or serendipity when something unexpected arises. Instead, invest in preparing for a range of possibilities – diversify your skill sets, cultivate curiosity, and build your networks.

- Assess your skills : What is academic research training you for? In part, academic research training is about asking important research questions, developing and pursuing methods to answer those questions, and using results to define outcomes and your next questions. You are also learning how to work in teams, how to deliver results, and a full range of transferable skills . Learn to talk about your skills and interests in broader more generalizable terms than perhaps your specific, immediate research project may suggest.

- Assess your strengths, passion, work style : Talk with your mentor team, or those who have worked with you and know you, and ask: “what do you think I am uniquely good at?” “What do you see as my top contribution(s) to a team or project?” Use free assessments like those offered by Doug’s Guides to get a better sense of what kind of work environment will be the best fit for you.

- Explore what is out there : Your research training alone is not career preparation, even for academic positions. You have to do something more proactive. Develop your “story” about who you are, what your passions are, and how you want to contribute. What opportunities exist? Ask people: I think your job sounds really interesting. How did you get here? Cultivate an opening question “I’m new to this industry/sector, can you tell me what you do?” Get involved with more than just building technical skills in your laboratory.

- Understand impact : Learn what is valued and expected in each kind of organization and work setting. Ask: “what does success or impact look like here in this sector, in this organization”? And then ask yourself – is that metric of success and impact meaningful for me. Is this how I want to contribute, and where my strengths lie.

- Gain experience : All the guests discussed the importance of getting out “there” and developing experience and exposure in other sectors, even for a short stint: giving a talk, participating in seminars/sessions that are open to others outside the organization, doing a short 4-12 week internship. These conversations and experiences will both help you decide what sector feels like a good fit for you, and will help distinguish you if you apply for a job in that sector.

Closing tips from speakers :

- Do something you care about.

- Summarize who you are without using your technical expertise as a crutch.

- Let go of worrying about what you are going to “be” – focus more on problems you are passionate about. Follow your curiosity and passion.

- Spend 5% of your time looking for a new job, even while happy in your current one.

- Develop relationships. They will take you places and open doors, and make your career worthwhile.

- Be kind, and humble. Be realistic about your limitations and acknowledge the contributions of others.

Power Skill of the Month : Pivot . Popularized in the start-up culture, “pivot” describes the ability to drop an unproductive direction or assess signs that suggest that the direction you are pursuing is not going to bear fruit. Having the ability to pivot to a new direction, release a direction that isn’t panning out, and move on with greater energy and opportunity is key regardless of what field or sector you may work in.

Originally posted on June 2, 2016.

Exploring Careers the Non-Linear Way

Career pathways are often viewed as linear. An imagined life scenario goes something like this: You go to college, get your first job, earn a promotion, get a graduate degree, move up the ladder to your dream job, secure that dream job, then happily retire–all within a few decades and all within the same company or organization. However, industry trends and professionals in our networks have increasingly told us a different story: before, throughout and beyond graduate school, people are following career trajectories that are non-linear and often include, various work experiences and projects that not only enhance the skillsets they already had as graduate students, these experiences allowed them to acquire new sets of tools to pursue their passions.

As you plan ahead, we encourage to think expansively about your professional endeavors. Instead of asking yourself, “What job title do I want to have?,” ask yourself, “What work experiences do I want?”

Here a few tips to get you started:

Managing social expectations. Social messages can impact the career choices we make now and into the future. These messages have the potential to tell us who we “should” be and come from our families, peers, broader community, and an array of institutions around us–this even includes the UW. Sometimes external messages do resonate with our professional endeavors and that’s great! When the messages don’t align with your goals, it’s perfectly okay to take a step back and reflect on your values and strengths in order to switch gears and create roadmaps to do work that excites you, or at least piques your interest.

Flexibility. One skill you’re amazing at in graduate school is being flexible. You’re adept at juggling multiple campus, work and personal responsibilities. Take advantage of your ability to be flexible and remain open to opportunities that provide you with a range of professional experiences. (1) Volunteer a few hours a week (or per month) at a local non-profit and see if your passion lies there. (2) Learn more about a specific job or work culture by arranging a job shadow. (3) If internships or practicum aren’t part of your degree requirements, but you’d like (paid or unpaid) work experience, seek out internship opportunities that work with your schedule. All of these experiences have the potential to broaden your professional networks. And wider networks increase the likelihood of successful job searches and setting up interviews. Volunteering, interning and job shadowing can also help you rule-out options based on first-hand experience, and this frees you up to explore other paths.

Do versus be. Rather than focus on who you want to be (e.g. a person with a static job title), think of the contributions you want to make in your community, with your peers, to your family. How you work is also important. Can you bring your authentic self (values, strengths, ethics) to work? Are you able to start your day from a place of integrity–regardless of whether you’re in an entry-level position or higher? Does doing the work involve more positive stress than negative stress? Is there room to face challenges that will help you grow professionally? Focusing on contributions, rather than job titles, can help you think more broadly about how work can be meaningful to you.

Failing forward. Doing what you love is an iterative process, not without trial and error. Don’t be afraid to take risks, but don’t be careless about the risks you take. Have a new project idea? Share it with colleagues, especially if you notice gaps or issues not already being addressed in your field. Start with a soft launch, on a smaller scale. If your project doesn’t produce the results you imagined, ask yourself the following questions: What went well? What can I learn from this? What would I do differently? Focus on the process and then move forward, and keep challenging yourself to grow.

Kelly, Jaye & Ziyan Core Programs Team

Tips from Employers to Guide Your Career Search

A few weeks ago, Core Programs in the Graduate School, Career Center, and the Alumni Association sponsored an employer panel for graduate students and postdocs. We would like to share a few pearls from the terrific UW alums who sat on the panel and who also hosted conversations during the networking reception that followed.

The job search is about finding the right fit for your talents. Be creative about your career options, test out new ways to tell the story of your (deep) experience and skill set, and it is never too early to start exploring and building your network.

Getting Started

- Evolve your resume. Your resume should always be evolving and tailored to each job you are applying for. Also, describe examples of specific accomplishments, including those that came up during your education and training. What problems did you approach, how did you solve them, with what results? Find out more about building your resume here. If you’re interested in careers beyond academia, here are tips on how to revise your CV into resume format.

- Build your experience. Find out what key skills or top tools are used and needed in the field of interest, and learn them. Look at the whole picture of your experience, inside and outside of graduate education. Align your skill sets to particular positions or organizations. Use specific examples in your talking points and written materials with the goal of making yourself stand out from an applicant pool. Learn how to get internship and related experential skills as graduate students at this upcoming workshop.

- Demonstrate excellent communication skills (in writing and in person). Be able to discuss complex ideas in a simple, clear, concise fashion. Be ready to describe the research you are working on in 30 seconds or less–and in a way that anyone can understand.

- Consider entry-level positions. Don’t get discouraged by entry-level positions. It can be helpful to get your foot in the door, demonstrate your contribution and capability. Depending on the organization (check this out first), you can move up within 3-6 months.

- Find your passion. Pay attention to your energy and passion as those are the kinds of jobs you should be looking for (and not others!).

- Start early. It is never too early to start building and growing your network. Networking is possible even for those of us who initially shy away from it.

- Talk about your talent and passion. Practice. Get comfortable. Own it, but without arrogance. Do mock interviews.

- Set up networking meetings. Identify target companies to narrow your options, and then set up informational interviews.

- Use LinkedIn strategically. Start with classmates, alums, professors. Join LinkedIn groups in order to initiate professional connections and learn about new job postings.

- Attend receptions. Face-to-face conversations can spark interest and connections at these professional gatherings. Send a resume to those you’ve connected with as a follow up. Personal connections always move a resume up if it is already in the pool.

- Ask questions. You are interviewing the informant and the organization to determine fit as much as they are interviewing you. Show them you want to know what the work is like, that it matters to you (that is, you aren’t just looking for “a job”). Questions you can ask: What is your day-to-day work like? What is the best part of what you do? The most challenging? What is the culture like here? What would you change about your job (or the organization) if you could?

Interviewing

- Phone interview. Always prepare for this as you would an in-person interview, and follow up with a thank you email or note.

- Answering technical questions. If a potential employer asks you a technical question, or to solve a technical problem during the interview, how should you handle it? The interviewer mostly wants to know how you strategize solving a problem. It is important to show how you would approach the problem, what you’d consider, and why.

- Be relationally savvy. Organizations are looking for people who will be colleagues.

- Show resilience. You can’t always control what interviewers will ask or how they will behave. Show some resilience and keep your composure, as well as keeping things in perspective. If you don’t like how you were treated in an interview, chances are you don’t want to work there anyway!

- Not hearing back. You might not hear back. Be persistent. Keep honing your materials and learning from the process.

Best Wishes on Your Career Paths!

Kelly, Jaye, and Ziyan Core Programs Team

Finding the Right Fit for Your Talent

In late January 2016, the Graduate School co-hosted an annual Career Symposium for graduate students and postdocs. We wanted to share just a few pearls from the terrific UW alums who sat on the panel and also hosted conversations during the networking reception. Bottom line : the job search is about finding the right fit for your talent. Be creative about your career options, test out new ways to tell the story of your (deep) experience and skill set, and it is never too early to start exploring and building your network.

- Evolve your resume . Your resume should always be evolving. Describe examples of specific accomplishments, including those that came up during your education and training. What problems did you approach, how did you solve them, with what results?

- Build your experience . Find out what the key skills or top tools are used in the field of interest, and learn them. Look at the whole picture of your experience, inside and outside of graduate education. Align your skill sets to particular positions or organizations. Use specific examples in your talking points and written materials with the goal of making yourself stand out from an applicant pool.

- Demonstrate excellent communication skills (in writing and in person) . Be able to discuss complex ideas in a simple, clear, concise fashion. Especially, be ready to describe what you are working on for your research in 30 seconds or less in a way that anyone can understand.

- Consider entry-level positions . Don’t get discouraged by entry-level positions. It can be helpful to get your foot in the door, demonstrate your contribution and capability and depending on the organization (check this out first) you can move up within 3-6 months.

- Find your passion . Pay attention to your energy and passion as those are the kinds of jobs you should be looking for (and not others!).

- Start early . It is never too early to start building and growing your network.

- Talk about your talent and passion . Practice. Get comfortable. Own it, but without arrogance. Do mock interviews.

- Set up networking meetings – informational interviews . Identify target companies to start with to narrow your options.

- Use LinkedIn strategically . Start with classmates, alums, professors. Join groups that might create good professional connections.

- Attend receptions . Send a resume to those you’ve connected with as a follow up. Personal connections always move a resume up if it is already in the pool. Face-to-face meetings spark interest and connection.

- Ask questions . You are interviewing the informant and the organization to determine fit as much as they are interviewing you. Show them you want to know what the work is like, that it matters to you (that is, you aren’t just looking for “a job”). Questions you can ask: what is your day-to-day work like? What is the best part of what you do? The most challenging? What is the culture like here? What would you change about your job (or the organization) if you could?

- Phone interview . Phone interviews are important. Always prepare as you would for an in-person, and follow up with a thank you email or note.

- Answering technical questions . If they ask you a technical question, or to solve a technical problem during the interview, how should you handle it? The interviewers mostly want to know how you think rather than the answer to the problem. It is important to show how you would approach the problem, what you’d consider, and why.

- Be relationally savvy . Organizations are looking for people who will be colleagues.

- Show resilience . You can’t always control what interviewers will ask or how they will behave. Show some resilience and keep your composure, as well as keeping things in perspective. If you don’t like how you were treated in an interview, chances are you don’t want to work there anyway!

- Not hearing back . You might not hear back. Have persistence. Keep honing your materials and learning from the process.

“ Interviews are helpful as I can tell right away if someone has the logic skills of a squirrel .” – Mike Bardaro (UW Chemistry alum), Senior Data Scientist AOL

Originally posted on January 28, 2016.

You’re Hired!

I feel behind my cohort in terms of applicable experience. I’ve applied to several internships/practicum experiences, but my financial situation dictates that I either need a paid internship or another job while I complete an unpaid internship. Because my classes are during the day, I’ve found the latter next to impossible. Additionally, I haven’t revived much interest in hiring due to my lack of experience. How do I find the right positions for this situation? —Inexperienced

(This week’s answer is courtesy of Catherine Basl, Lead Career Counselor, Career Center .)

Thanks for sharing a bit about your situation. It can definitely feel discouraging when we aren’t having as much luck as we want in the job search and when we are faced with hard decisions about lackluster paid positions versus highly interesting unpaid positions. Below are some tips you might find helpful.

- Don’t worry! Most graduate cohorts are made up of students who have a range of applicable experience. If they accepted you into the program, they think you have enough experience to be successful! Though it can be difficult, try to stay positive and confident.

- Consider making a list of what you are looking for in a job or internship. Whether it includes a desired weekly schedule, skills, location, or something else, making a list and prioritizing it can help when mulling over possible options.

- Applicable experience is more than work experience. Consider your volunteer experience too! If you are within a few years of your undergraduate work you might also include relevant clubs and student activities on your resume. Don’t sell yourself short.

- Use your network! If you have only been looking online, consult with your graduate program adviser, departmental staff members and faculty about possible internships. Depending on your field, HuskyJobs might also be a good resource.

- Polish your resume and cover letter! Tailor your resume and cover letter for each position and consider getting them reviewed to ensure they are submission-ready. Sometimes tweaking your materials or doing a mock interview can make a world of difference in the job search.

- Feeling stuck? Schedule an appointment with a career counselor—we can help you with every step of the process from deciding what’s most important to you to helping you prep for the interview that will land you your dream internship.

Ask the Grad School Guru is an advice column for all y’all graduate and professional students. Real questions from real students, answered by real people. If the guru doesn’t know the answer, the guru will seek out experts all across campus to address the issue. (Please note: The guru is not a medical doctor, therapist, lawyer or academic advisor, and all advice offered here is for informational purposes only.) Submit a question for the column →

- Browse by collections

- Arts, Design, Entertainment + Communications

- Data, Analytics, Technology + Engineering

- Government, Law, International Affairs + Policy

- Healthcare, Public Health, Life + Lab Sciences

- Management, Sales, Consulting + Finance

- Nonprofit, Education + Social Impact

- BIPOC (Black Indigenous People of Color)

- International Students

- Neurodiverse & Students with Disabilities

- Proud to be first

10 Transferable Skills from Your PhD that Employers Want

- Share This: Share 10 Transferable Skills from Your PhD that Employers Want on Facebook Share 10 Transferable Skills from Your PhD that Employers Want on LinkedIn Share 10 Transferable Skills from Your PhD that Employers Want on X

Source: Beyond the Professoriate

In a job interview, an employer may ask you: “What skills do you bring to this position?”

Do you know how to answer this question?

You may be surprised to find out that your PhD may not be your most important asset. In addition to your work experience and education, employers in the private sector pay close attention to your core skill set.

The good news is that you have valuable skills as a PhD. You have transferable skills that employers want. A transferable skill is a skill you have used in one work context (in this case, in higher education), and that you can use in a different work context (e.g. in government, at a non-profit, in a corporate setting).

When speaking with employers or when crafting job documents, you need to clearly articulate your skills and illustrate how they are relevant to the specific role you are seeking. You will be translating your academic experience using language that is familiar to the employer.