Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 08 July 2022

A critical examination of a community-led ecovillage initiative: a case of Auroville, India

- Abhishek Koduvayur Venkitaraman ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8515-257X 1 &

- Neelakshi Joshi ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8947-1893 2

Climate Action volume 1 , Article number: 15 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

7225 Accesses

2 Citations

6 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Sustainability

Human settlements across the world are attempting to address climate change, leading to changing paradigms, parameters, and indicators for defining the path to future sustainability. In this regard, the term ecovillage has been increasingly used as models for sustainable human settlements. While the term is new, the concept is an old one: human development in harmony with nature. However, materially realizing the concept of an ecovillage is not without challenges. These include challenges in scaling up and transferability, negative regional impacts and struggles of functioning within larger capitalistic and growth-oriented systems. This paper presents the case of Auroville, an early attempt to establish an ecovillage in Southern India. We draw primarily from the ethnographic living and working experience of the authors in Auroville as well as published academic literature and newspaper articles. We find that Auroville has proven to be a successful laboratory for providing bottom-up, low cost and context-specific ecological solutions to the challenges of sustainability. However, challenges of economic and social sustainability compound as the town attempts to scale up and grow.

Graphical abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Severe decline in large farmland trees in India over the past decade

Urbanization and regional climate change-linked warming of Indian cities

A unifying modelling of multiple land degradation pathways in Europe

Introduction.

Scientists have repeatedly argued and emphasized for an equilibrium between human development and the basic ecological support systems of the planet (IPCC 2014 ; United Nations 1987 ). Human settlements have been important in this regard as places of concentrated human activity (Edward & Matthew E, 2010 ; Scott and Storper 2015 ). Settlement planning has responded to this call through visions of the eco-city as a proposal for building the city like a living system with a land use pattern supporting the healthy anatomy of the whole city and enhance its biodiversity, while resonating its functions with sustainability (Barton 2013 ; Register 1987 ; Roseland 1997 ). In planning practice, this means balancing between economic growth, social justice, and environmental well-being (Campbell 1996 ). However, the concept of eco-cities remains top-down in its approach with city authorities taking a lead in involving the civil society and citizens to implement the city’s environment plan (Joss 2010a , b ).

Contrary to the idea of eco-cities, ecovillages are small-scale, bottom-up sites for experimentation around sustainable living. Ecovillages resonate the same core principles of an eco-city but combine the social, ecological, and spiritual aspects of human existence (Gilman 1991 ). Findhorn Ecovillage in Scotland is one of the oldest and most prominent ecovillages in the world and has collaborations with the United Nations and was named as a best practice community (Lockyer and Veteto 2013 ).

Another notable example is the Transitions Town movement that started in Totnes, United Kingdom but has now spread all over the world (Hopkins 2008 ; Smith 2011 ). The movement focuses upon supporting community-led responses to peak oil and climate change, building resilience and happiness. Additionally, it emphasizes rebuilding local agriculture and food production, localizing energy production along with rediscovering local building materials in the context of zero energy building (Hopkins 2008 ). Ecological districts within the urban fabric are also termed as ecovillages (Wolfram 2017 ).

Ecovillages are intentional communities characterized by alternative lifestyles, values, economics and governance systems (Joss 2010a , b ; Ergas 2010 ). At the same time ecovillages are located within and interact with growth-oriented capitalistic systems (Price et al. 2020 ). This dichotomy presents a challenge for ecovillages as they put ideas of sustainability transformation into practice. We explore some of these contradictions through the case study of Auroville, an ecovillage located in southern India. A discussion on the gaps between the ideas of an ecovillage against their lived reality throws light upon the challenges that ecovillages face when they attempt to grow. We begin by elaborating the key characteristics of ecovillages in the “Characteristics of ecovillages” section. We then present our material and methods in the “Methodology” section. Furthermore, we use the key characteristics of an ecovillage as a framework for analysing and discussing Auroville in the “Auroville, an ecovillage in South India” and “Discussion” sections. We conclude with a reflection on the concept of ecovillages.

Characteristics of ecovillages

The concept of an ecovillage is broad and has multiple interpretations. Based on a reading of the existing literature on ecovillages, we summarize some of their key characteristics here:

Alternative lifestyles and values : Ecovillage can be seen as intentional communities (Ergas 2010 ) and social movements which have a common stance against unsustainable modes of living and working (Kirby 2003 ; Snow et al. 2004 ). Ecovillages advocate for achieving an alternate lifestyle involving a considerable shift in power from globalized values to those internalized in local community autonomy. Therefore many ecovillages aspire to restructure power distribution and foster a spirit of collective and transparent decision-making (Boyer 2015 ; Cunningham and Wearing 2013 ). However, it is difficult to convince many people to believe in a common value system since the vision is to establish a world that is not only ecologically sustainable but also personally rewarding in terms of self-sacrifice for a good cause (Anderson 2015 ).

Governance : ecovillages tend to rely on a community-based governance and there is an assumption that the local and regional communities respond more effectively to local environmental problems since these problems pertain to the local context and priorities (Van Bussel et al. 2020 ). In a community-based governance system, activities are organized and carried out through participatory democracy committed to consensual decision-making. However, participatory democracy has its own set of problems. Consensual decision-making is time-consuming, and the degree of participation tends to vary from time to time (Fischer 2017 ). Participatory processes have also been criticized on the grounds for slowing down the decision-making process and resulting in a weak final agreement which doesn’t balance competing interests (Alterman et al. 1984 ).

Economic models in an ecovillages : ecovillages have attempted to combine economic objectives along with the overall well-being of people and have experimented with budgetary solutions appealing to a wider society (Hall 2015 ). As grassroots initiatives, ecovillages have advocated and practised living in community economies (Roelvink and Gibson-Graham 2009 ) and have influenced twentieth century economic practices beyond their geographical boundaries (Boyer 2015 ). Due to the emphasis on sharing in ecovillages, they can be considered to accommodate diverse economies (Gibson-Graham 2008 ) where human needs are met through relational exchanges and non-monetary practices, highlighting strong social ties (Waerther 2014 ). In some ecovillages, living expenses are reduced by sharing costly assets and saving cost on building materials by bulk buying and growing food for community consumption and sale (Pickerill 2017 ). These economic models have their own merit but are perhaps insufficient for the long-term economic sustainability of ecovillages (Price et al. 2020 ). Eventually, ecovillages might have to rely on external sources to import goods and services which cannot be produced on-site. This contradicts the ecovillage principles of being a self-reliant economy, reduction of its carbon footprint and minimizing resource consumption, thus implying a dependence on the market economy of the region (Bauhardt 2014 ).

Self-sufficiency : fulfilling the community’s needs within the available resources is a cornerstone principle for many ecovillages (Gilman 1991 ). This is often achieved through organic farming, permaculture, renewable energy and co-housing. Such measures are an attempt to offset and mitigate unsustainable development and limit the ecovillage’s ecological footprint (Litfin 2009 ). The initial small scale of the community often allows for this. However, as ecovillages grow in size and complexity, the interconnectedness and inter-dependence to the surrounding space become more apparent (Joss 2010a , b ). Examples include drawing resources from central energy and water systems (Xue 2014 ). Furthermore, ecovillages might turn out to be desirable places to live, with better quality of life, driving up land and property prices in the region as well as carbon emissions with additional visitors (Mössner and Miller 2015 ). Furthermore, in their role as catalysts of change in transforming society, ecovillages need to interact with their external surroundings and neighbouring communities, the municipalities, and the state and national level policies (Dawson and Lucas 2006 ; Kim 2016 ). This is particularly relevant in the Global South, where the ecovillage development has the potential to drive regional-scale sustainable development.

The characteristics of an ecovillage, however, do not exist in a geographical vacuum. Scholarly understanding of ecovillages as bottom-up efforts to drive sustainability transitions largely draw from the experiences of the Global North (Wagner 2012 ). Such ecovillage models often challenge the dominant capitalistic paradigm of post-industrial development, overconsumption and growth. Locating ecovillages in the Global South requires an expansion or re-evaluation of their larger socio-economic context as well as their socio-ecological impacts (Dias et al. 2017 ; Litfin 2009 ) .

To build upon the opportunities and challenges of ecovillages, locating them within the context of the Global South, we present the case of Auroville, an ecovillage located in southern India.

Methodology

We use the initial theoretical framework of ecovillage characteristics as a starting point for developing the case study of Auroville. Here, we draw from academic literature published about Auroville during 1968–2021. We also draw inferences from self-published reports and documents by the Auroville Foundation. Although we cover multiple interconnected aspects of Auroville, the characteristics pertaining to an ecovillage remain the focus of our work. We review the literature sources deductively, drawing on aspects of values, governance, economics and self-reliance, established in the previous section.

We triangulate the secondary data sources against our ethnographic experience of having lived and worked in Auroville for extended periods of time (2010–2012 and 2013–2014, respectively). We have worked in Auroville as architects and urban planners. During this time, we participated in multiple meetings on Auroville’s development as part of our work. We have discussed aspects of Auroville’s sustainability with Aurovillians working on diverse aspects, from urban planning to regional integration. Furthermore, living and working in Auroville brought us in conversation with several individuals from villages surrounding Auroville, employed in Auroville. For writing this case study, we have revisited our lived experience of Auroville through memory, research and work diaries maintained during this period, photographs as well our previously published research articles (Venkitaraman 2017 ; Walsky and Joshi 2013 ). Given our expertise in architecture and planning, we have also presented the translation of the key characteristics of an ecovillage, namely, alternative values, governance and economic systems and self-reliance, in these domains.

We acknowledge certain limitations to our methodology. We rely largely on secondary data to expand upon the challenges and contradictions in an ecovillage. We have attempted to overcome this by drawing from our first-hand experience of having lived in Auroville. Although our lived experiences are almost a decade old, we have attempted to compliment it with recently published articles as well as newspaper reports.

The next section presents Auroville as an ecovillage followed by a critical examination of its regional impact, governance, and economic structure.

Auroville, an ecovillage in South India

Foundational values.

Sri Aurobindo was an Indian philosopher and spiritual leader who believed that “man is a transitional being” and developed the practice of integral yoga with the aim of evolving humans into divine beings (Sen 2018 ). His spiritual consort, Mirra Alfassa realized his ideas in material form through a “universal township” which would hopefully contribute to “progress of humanity towards its splendid future”. Auroville was founded in 1968 by Mirra Alfassa, as a township near Pondicherry, India. Alfassa envisioned Auroville to be a “site of material and spiritual research for a living embodiment of an actual human unity” (Alfassa 1968 ). On 28 February 1968, the city was inaugurated with the support of UNESCO and the participation of people from 125 countries who each brought a handful of earth from their homelands to an urn that stands at its centre as a symbolic representation of human unity, the aim of the project. This spiritual foundation has guided the development of the socio-economic structure of Auroville for individual and collective growth (Shinn 1984 ). To translate these spiritual ideas into a material form, Mirra Alfassa provided simple sketches, a Charter, and guiding principles towards human unity (Sarkar 2015 ).

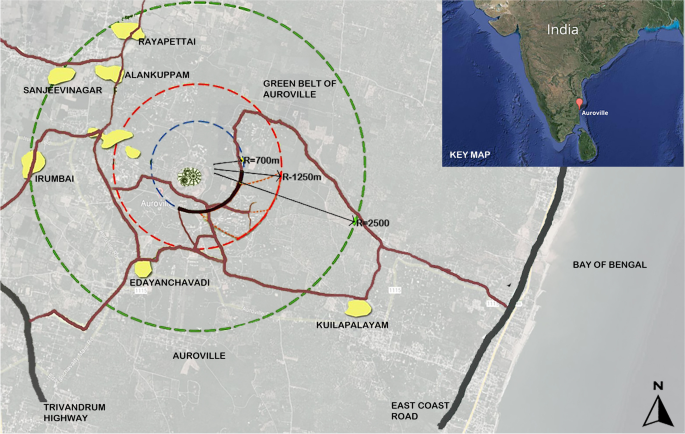

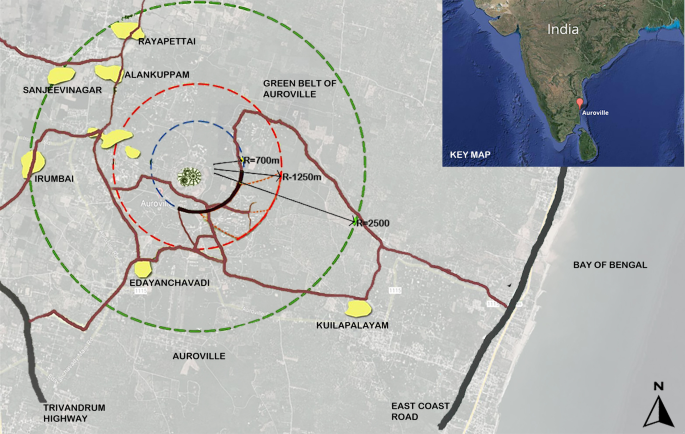

Roger Anger, a French architect translated Alfassa’s dream into the Auroville City Plan that continues to inform the physical development of Auroville (Kundoo 2009 ). The Auroville Masterplan 2025 envisions Auroville to be a circular township (Fig. 1 ) spread over a 20 sq. km (Auroville Foundation 2001 ). Initially planned for a population of 50,000 people, today Auroville today has 3305 residents hailing from 60 countries (Auroville Foundation 2021 ). Since its early days, there has been a divide between the “organicists” and the “constructionists” of Auroville (Kapur 2021 ). The organicists have a bottom-up vision of low impact and environmentally friendly development whereas the constructionists have a top-down vision of sticking with the original masterplan and realize an urban, dense version of Auroville.

A map of Auroville and its surrounding regions, with the main villages in the area

Auroville has served as a laboratory of low-cost and low-impact building construction, transportation, and city planning. Although the term sustainability has not been explicitly used in the Charter, it has been central to the city planning and building development process in Auroville (Walsky and Joshi 2013 ). Unlike many human settlements that negatively impact their ecology, the foundational project of Auroville was land restoration. The initial residents of Auroville were able to grow back parts of the Tropical Dry Evergreen Forest in and around Auroville using top-soil conservation and rainwater harvesting techniques (Blanchflower 2005 ). While the ecological restoration has been lauded both locally and globally, Namakkal ( 2012 ) argues that it is seldom acknowledged that the land was bought from local villagers at low prices and local labour was used to plant the forest as well as build the initial city. At the time of writing this paper, the Auroville Foundation still needs to secure 17% of the land in the city area and nearly 50% of the land for the green belt to realize the original masterplan. However, land prices have gone up substantially as have conflicts in acquiring this land for Auroville (Namakkal 2012 ).

Governance structure

While the Charter of Auroville says that “Auroville belongs to humanity as a whole” (Alfassa 1968 ), in reality, it is governed by a well-defined set of individuals. Auroville’s first few years, between 1968 and 1973, were guided directly by Mirra Alfassa. After her passing, there was a power struggle between the Sri Aurobindo Society, claiming control over the project, and the community members striving for autonomy (Kapur 2021 ).

The Government of India founded the Auroville Foundation Act in 1988 providing in the public interest, the acquisition of all assets and undertakings relatable to Auroville. These assets were ultimately vested in the Auroville Foundation which was formed in January 1991 (Auroville. 2015 ). The Auroville Foundation envisioned a notion of a planned future, resulting in a new masterplan in 1994. This masterplan encouraged participatory planning and recognized that the architectural vision needs to proceed in a democratic manner. This prompted the Auroville community to adopt a more structured form of governance. The Auroville Foundation has other governing institutions under it, namely: The Governing Board which has overall responsibility for Auroville’s development, The International Advisory Council, which advises the Governing Board on the management of the township and the Residents’ Assembly who organize activities relating to Auroville and formulate the master plan. Furthermore, there are committees and working groups for different aspects of development from waste management to building development.

Auroville is an example of the ‘bottom-up’ approach, in the sense that developments are decided and implemented by the community and the state level and national level governments get involved later (Sarkar 2015 ). An example of this is seen in the regular meetings held by the Town Development Council of Auroville which also conducted a weeklong workshop in 2019 for the community which covered themes such as place-making, dimensions of water and strategies for liveable cities and community planning (Ministry of Human Reource Development Government of India 2021 ).

Conflicts often arise between the interpretation of the initial masterplan and the present day realities and aspiration of the residents (Walsky and Joshi 2013 ). This is often rooted in the initial vision of Auroville as a city of 50,000 versus its current reality of being an ecovillage of around 3000 people. Spatially, this unusual growth pattern has been problematic in Auroville’s building and mobility planning (Venkitaraman 2017 ). At the time of writing this paper, there is a clash between the Residents’ Assembly and the Auroville Foundation over the felling of trees for the construction of the Crown Road project inside Auroville (The Hindu 2021 ). While the Residents’ Assembly wants a re-working of the original masterplan considering the ecological damage through tree cutting, the Auroville Foundation wants to move ahead with the original city vision.

Beyond its boundaries, Auroville is surrounded by numerous rural settlements, namely, Kuyilapalyam, Edayanchavadi, Alankuppam, Kottakarai, and Attankarai. The Auroville Village Action Group (AVAG) aims to help the village communities to strive towards sustainability and find plausible solutions to the problems of contemporary rural life. In September 1970, a charter was circulated among the sub-regional villages of Auroville, promising better employment opportunities and higher living standards with improved health and sanitation facilities (Social Research Centre Auroville 2005 ). Currently, there are about 13 groups for the development of the Auroville sub-region. However, Jukka ( 2006 ) points out that the regional development vision of Auroville is top-down and does not sufficiently engage with the villagers and their aspirations.

Auroville’s economic model

Auroville has also strived to move away from money as a foundation of society to a distinctive economic model exchange and sharing (Kapoor 2007 ). However, Auroville needs money to realize its multiple land and building projects. Auroville also receives various donations and grants. During 2018–2019, Auroville received around Rs. 2396 lakhs (around 4 million USD) under Foreign Contributions Regulation Act (FCRA) and other donations. The Central Government of India supports the Auroville Foundation with annual grants for Auroville’s management and for the running costs of the Secretariat of the Foundation, collectively known as Grant-in-Aid. Auroville received a total of Rs. 1463 lakhs (around 2 million USD) as Grant-in-Aid during 2018–2019. The income generated by Auroville during this time was Rs. 687 lakhs (around 91,000 USD) (Ministry of Human Reource Development Government of India 2021 ).

Presently, the economy of Auroville is based on manufacturing units and services with agriculture being an important sector, and currently, there are about 100 small and medium manufacturing units. The service sector of Auroville comprises of construction and architectural services and research and training in various sectors (Auroville Foundation 2001 ). In addition to this, tourism is another important source of income generation for Auroville. As per the Annual Report of Auroville Foundation, the donations and income have not been consistent over the years. In this regard, Auroville’s growth pattern in terms of the economy has not been linear and it does not mimic the usual growth patterns associated with the development of counterparts, in terms of capitalization, finance, governance, and on key issues such as distribution policies and ownership rights (Thomas and Thomas 2013 ).

Auroville also benefits from labour from the surrounding villages. The nature of employment provided in Auroville to villages remains largely in low-paying jobs (Namakkal 2012 ). It can be argued that the fruits of Auroville’s development have not been equally shared with the surrounding villages and a feeling of ‘us and them’ still pervades. Striving for human unity is the central tenet of Auroville (Shinn 1984 ), however, it has struggled to do so with its immediate neighbours.

Striving for self-sufficiency

Auroville has strived for self-sufficiency in terms of food production from local farms, energy production from renewable sources like solar and wind sources and waste management.

Many prominent buildings of Auroville have been designed keeping in mind the self-sufficiency principle in Auroville. For example, the Solar Kitchen was designed by architect Suhasini Ayer as a demonstration project to tap the solar energy potential of the region. At present, this building is used for cooking meals thrice a day for over 1000 people. The Solar Kitchen also supports the organic farming sector in Auroville by being the primary purchaser of the locally grown products (Ayer 1997 ). Another example is the Auroville Earth Institute, renowned for its Compressed and Stabilized Earth Block (CSEB) technique, which constitute natural and locally found soil as one of its main ingredients (Figs. 2 and 3 ).

Compressed earth blocks manufactured by Auroville Earth Institute

A residence in Auroville constructed using compressed earth blocks

However, it is important to acknowledge that Auroville does not exist as a 100% self-sufficient bubble. For example, food produced in Auroville provides for only 15% of the consumption (Auroville Foundation 2004 ). An initial attempt to calculate the ecological footprint of Auroville estimates it to be 2.5 Ha, against the average footprint of an Indian of 0.8 Ha (Greenberg 1998 ). Furthermore, though Auroville has strived for material innovation in architecture, it has not been successful in achieving 25 sq. metres as the limit to individual living space (Walsky and Joshi 2013 ). This challenges the notion of Auroville continuing to be an ecovillage if it aspires to be a city of 50,000 people and might end up having substantial ecological impact on its surroundings.

Urban sustainability transformation in a rapidly urbanizing world runs into the risk of focusing on technological fixes while overlooking the social and ecological impacts of growth. In this light, bottom-up initiatives like ecovillages serve as a laboratory for testing alternative and holistic models of development. Auroville, a 53-year-old ecovillage in southern India, has achieved this to a certain extent. Auroville is a showcase of land regeneration, biodiversity restoration, alternative building technologies as well as experimentations in alternative governance and economic models. In this paper, we have critically examined some achievements and challenges that Auroville has faced in realizing its initial vision of being a “city that the world needs” (Alfassa 1968 ). Lessons learnt from Auroville help deepen our understanding of ecovillages as sites of fostering alternative development practices. Here we discuss three aspects of this research:

Alternate lifestyles and values in the context of an ecovillage : Ecovillages are niches providing space for realizing alternative values and lifestyles. However, ecovillages seldom exist in a vacuum. They are physically situated in existing societies and economies. Although residents in an ecovillage seek to achieve collective identity by creating an alternative society, an ecovillage is embedded within a larger culture and thus, the prevailing ideologies of the dominant society affect the ecovillage (Ergas 2010 ) as seen in Auroville. This can be noticed between the material and knowledge flows in and out of Auroville. Furthermore, the India of the 1970s when Auroville was born with socialist values is very different from present-day India where material and capitalistic aspirations are on the rise. These are reflected in higher land prices and living costs in and around Auroville. Amidst the transforming political landscape of India in the 1970s, there were implications which were seen in the character of architectural production. Auroville welcomed and immersed itself into this era of experimentation. These developments form an integral part of the ethos of Auroville. To achieve its initial visions, Auroville depends on multiple external economic sources. In analysing ecovillages, it is important to critically examine the broader context within which they are located and how they influence and, in turn, are influenced by their contexts.

Even though Auroville’s architects and urban planners remain committed to their belief that architecture is a primary tool of community - building, decades later, the developments seem to have progressed at a slow pace. The number of permanently settled residents in Auroville has barely reached 2000 currently and the overall urban design remains fragmentary. Despite witnessing a slower rate of progress, it has been able to sustain a culture of innovation and Auroville remains utopian in its aim to create an alternative lifestyle (Scriver and Srivastava 2016 ).

Governance, economy, and self-sufficiency in an ecovillage that wants to be an eco-city : In growth-based societies, ecovillages present the possibility of providing an alternative vision of degrowth (Xue 2014 ). However, Auroville currently functions as an ecovillage that aspires to be an eco-city as per its initial masterplan. This growth-based model sometimes conflicts with Auroville’s vision of being a self-reliant, non-monetary society. Given the urgent need to remain within our planetary limits, ecovillages like Auroville could re-evaluate their initial growth-based visions and explore alternatives for achieving sustainability and well-being. The visions of ecovillages should thus not be set in stone, but rather remain flexible to evolving ideas and practices (Ergas 2010 ).

Similarly, governance structures might need a re-evaluation with changing priorities within the ecovillage as well as a need to be inclusive of regional visions and voices. It would be intriguing to explore on what kind of governance model/leadership is best suited to fulfil the aims of an ecovillage. Auroville seems to follow the elements of sustainability-oriented governance: empowerment, engagement, communication, openness and transparency (Bubna-Litic 2008 ), yet it is seen that conflicts arise. One solution to this could be greater external engagement with government and continuing to engage the external community about Auroville. Generally, intentional communities are organized by embracing the ideology of consensus, but it remains to be seen whether the consensus decision-making model works to its full potential in the context of alternative lifestyles. When individuals seek alternative lifestyles in the current world, there is a shift from globalized values towards local community autonomy, this shift demands a need for processes that allow for a different and more equitable approach to governance (Cunningham and Wearing 2013 ).

Ecovillages in the Global South : Situating ecovillages in the Global South requires a nuanced examination of the social, economic, and environmental aspects of sustainability that the ecovillage aims to achieve (Dias et al. 2017 ; Litfin 2009 ). In the case of Auroville, Auroville has helped bring back ecologically restorative practices in forestry, agriculture, and architecture in the region. However, the average Aurovillian has a higher standard of living than the neighbouring villagers. This in-turn influences the material consumption practices within the community. The lessons in sustainable living, in ecovillages located in the Global South, need not be unidirectional (from the ecovillage to the surrounding society). Rather, the ecovillage also stands to lean from the existing models of low-impact living.

Ecovillages in the Global South such as Auroville face similar problems related to Governance as seen in some other ecovillages in the developed world such as The Aldinga Arts Village in South Australia (Bubna-Litic 2008 ) and in Sweden (Bardici 2014 ). However, despite the issues related to consensus in Governance, the ecovillages are noted for their sustainable innovations.

Auroville’s sustainable measures have been endorsed by the Government of India as well. The Auroville Master Plan for 2000–2025 has been dedicated to creating an environmentally sustainable urban settlement which integrates the neighbourhood rural areas. The surrounding Green Belt, intended to be a fertile zone is presently being used for applied research in various sectors such as water management, food production, and soil conservation. The results promise a replicable model which could be used in urban and rural areas alike (Kapoor 2007 ).

To address the expansion and re-evaluation of the larger socio-economic context of Auroville and its socio-ecological impacts, as enunciated by Dias et al. ( 2017 ) and Kutting and Lipschutz (2009), a proposal for a sustainable regional plan was prepared in 2012 jointly by Government of India, ADEME (French Environment and Energy Management Agency), INTACH (Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage) and PondyCAN (An NGO which works to preserve and enhance the natural, social, cultural and spiritual environment of Pondicherry). The report was prepared and aimed to be a way forward for unique and diverse communities to grow together as a single entity and to develop a holistic model for future development in this region. This report takes into consideration the surrounding villages and districts around Auroville: Puducherry, Viluppuram and Cuddalore (ADEME, INTACH, PondyCAN,, and Government of India 2012 ).

The concept of eco-cities in urban planning is defined as utopias, hard to achieve standards of human settlements. Ecovillages emerge as small-scale realization of the ideas of an eco-city. Over the years, the alternative practices of Auroville have served as an educational platform for researchers, students, and the civil society alike. However, realizing alternative ecological lifestyles, governance and economic system and self-sufficiency struggle with challenges and contradictions as the ecovillage interact with a larger growth-oriented capitalistic system. Although ecovillages are sites of experimentation, they are seldom insular space. Regional impacts of and on ecovillage are important in analysing their developmental trajectories. Finally, the vision of ecovillages needs to evolve as the ecovillage as well is surroundings grow and change. Experiments in ecovillages like Auroville remind us that alternative visions of human settlements come with opportunities and challenges and are a work-in-progress in achieving a more sustainable future. There is further potential to understand the consensus-based approach and the governance models in an ecovillage in a better manner.

It can be deduced from the findings that ecovillages as catalysts of urban sustainability have a lot of potentials and challenges. The potential is in terms of devising an alternate lifestyle based on an alternative style of governance while the challenges include the local ecological impact and the difficulty in consensus about certain things. There is a future possibility to explore other conditions which facilitate the mainstream translation of ecovillage practices and how future ecovillages can progress to the next level (Kim 2016 ; Norbeck 1999 ).

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

ADEME, INTACH, PondyCAN, & Government of India (2012) Sustainable Regional Planning Framework for Puducherry. Viluppuram, Auroville and Cuddalore

Google Scholar

Alfassa, M. (1968). The Auroville Charter: a new vision of power and promise for people choosing another way of life. https://auroville.org/contents/1

Alterman R, Harris D, Hill M (1984) The impact of public participation on planning: the case of the Derbyshire Structure Plan ( UK). Town Plann Rev 55 (2):177–196. https://doi.org/10.3828/tpr.55.2.f78767r1xu185563

Article Google Scholar

Anderson E (2015) Prologue. In: Lockyer J, Veteto JR (eds) Environmental Anthropology Engaging Ecotopia: Bioregionalism, Permaculture, and Ecovillages. Oxford, pp 1–18

Auroville Foundation. (2004). No Title.

Auroville Foundation. (2021). Auroville Census.

Auroville SRC (2005) Socio-economic survey of Auroville employees, p 2000

Auroville. (2015). Orgnaisational History and Involvement of Government of India. https://auroville.org/contents/850

Ayer S (1997) Auroville Design Consultants

Bardici VM (2014) A discourse analysis of Eco-city in the Swedish urban context - construction, cultural bias, selectivity, framing and political action, p 32

Barton, H. (2013). Sustainable Communities. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315870649

Bauhardt C (2014) Solutions to the crisis? The Green New Deal, Degrowth, and the Solidarity Economy: Alternatives to the capitalist growth economy from an ecofeminist economics perspective. Ecol Econ 102 :60–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2014.03.015

Blanchflower P (2005) Restoration of the Tropical Dry Evergreen Forest of Peninsular India. Biodiversity 6(1):17–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/14888386.2005.9712755

Boyer RHW (2015) Grassroots innovation for urban sustainability: comparing the diffusion pathways of three ecovillage projects. Environ Plann A Econ Space 47(2):320–337. https://doi.org/10.1068/a140250p

Bubna-Litic K (2008) The Aldinga Arts Ecovillage. Governance for Sustainability, pp 93–102

Campbell S (1996) Green Cities, Growing Cities, Just Cities?: Urban Planning and the Contradictions of Sustainable Development. J Am Plann Assoc 62 (3):296–312. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944369608975696

Cunningham PA, Wearing SL (2013) The Politics of Consensus: An Exploration of the Cloughjordan Ecovillage, Ireland. Cosmopolitan Civil Soc 5:1–28 https://opus.lib.uts.edu.au/handle/10453/27731

Dawson, J., & Lucas, C. (2006). Ecovillages: new frontiers for sustainability. Green Books.

Dias MA, Loureiro CFB, Chevitarese L, Souza CDME (2017) The meaning and relevance of ecovillages for the construction of sustainable soceital alternatives. Ambiente Sociedade 20(3):79–96. https://doi.org/10.1590/1809-4422asoc0083v2032017

Edward G, Matthew E, K. (2010) The greenness of cities;Carbon dioxide emissions and urban development. J Urban Econ 67(3):404–418

Ergas C (2010) A model of sustainable living: Collective identity in an urban ecovillage. Organ Environ 23 (1):32–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/1086026609360324

Fischer F (2017) Practicing Participatory Environmental Governance: Ecovillages and the Global Ecovillage Movement. In: Climate Crisis and the Democratic Prospect :Participatory Governance in Sustainable Communities, Oxford, pp 185–207. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780199594917.001.0001

Foundation A (2001) The Auroville Universal Township Master Plan , Perspective, p 2025 https://www.auroville.info/ACUR/masterplan/index.htm

Gibson-Graham J (2008) Diverse Economies:performative practices for “other worlds.”. Progress Human Geography 32(5):613–632

Gilman, R. (1991). The Eco-Village Challenge. In Context. https://www.context.org/iclib/ic29/

Greenberg, D. (1998). Auroville’s Ecological Footprints. Geocommons.

Hall R (2015) The ecovillage experience as an evidence base for national wellbeing strategies. Intellect Econ 9 (1):30–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intele.2015.07.001

The Hindu. (2021). Auroville residents protest uprooting of trees for contentious Crown Project. The Hindu. https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/tamil-nadu/auroville-residents-protest-uprooting-of-trees-for-contentious-crown-project/article37835625.ece#

Hopkins R (2008) The Transition Handbook From Oil Dependency to Local Resilience

IPCC (2014) Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. In: Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

Joss S (2010a) Eco-cities: A global survey 2009. WIT Transact Ecol Environ 129:239–250. https://doi.org/10.2495/SC100211

Joss, Simon. (2010b). Eco-Cities — A Global Survey 2009 Part A : Eco-City Profiles. Governance & Sustainability: Innovating for Environmental & Technological Futures, May.

Jukka, J. (2006). Jukka Jouhki Imagining the Other Orientalism and Occidentalism in Tamil-European Relations in South India. In Building (Issue September).

Kapoor R (2007) Auroville: A spiritual-social experiment in human unity and evolution. Futures 39(5):632–643. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2006.10.009

Kapur, A. (2021). Better to Have Gone: Love, Death, and the Quest for Utopia in Auroville. Scribner Book Company.

Kim MY (2016) The Influences of an Eco-village towards Urban Sustainability: A case study of two Swedish eco-villages

Kirby A (2003) Redefining social and environmental relations at the ecovillage at Ithaca: A case study. J Environ Psycho 23 (3):323–332. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-4944(03)00025-2

Kundoo A (2009) Roger Anger: research on beauty: architecture. Jovis, pp 1953–2008

Litfin K (2009) Reinventing the future: The global ecovillage movement as a holistic knowledge community. In: Kütting G, Lipschutz R (eds) Environmental Governance: Knowledge and Power in a Local-Global World. Routledge, pp 124–142. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203880104

Chapter Google Scholar

Lockyer J, Veteto JR (2013) Environmental Anthropology Engaging Ecotopia

Ministry of Human Reource Development Government of India. (2021). Auroville Foundation: Annual Report and Accounts(2018-19). https://aurovillefoundation.org.in/publications/annual-report/

Mössner S, Miller B (2015) Sustainability in One Place? Dilemmas of Sustainability Governance in the Freiburg Metropolitan Region. Regions Magazine 300(1):18–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/13673882.2015.11668692

Namakkal J (2012) European Dreams, Tamil Land: Auroville and the Paradox of a Postcolonial Utopia. J Study Radicalism 6 (1):59–88. https://doi.org/10.1353/jsr.2012.0006

Norbeck, M. (1999). Individual Community Environment: Lessons from nine Swedish ecovillages. http://www.ekoby.org/index.html

Pickerill J (2017) What are we fighting for? Ideological posturing and anarchist geographies. Dial Human Geography 7 (3):251–256. https://doi.org/10.1177/2043820617732914

Price OM, Ville S, Heffernan E, Gibbons B, Johnsson M (2020) Finding convergence: Economic perspectives and the economic practices of an Australian ecovillage. Environ Innov Soc Trans 34(April 2019):209–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2019.12.007

Register, R. (1987). Ecocity Berkeley : building cities for a healthy future. Berkeley, Calif. : North Atlantic Books, 1987. https://search.library.wisc.edu/catalog/9910124360102121

Roelvink G, Gibson-Graham J (2009) A Postcaptialist politics of dwelling:ecological humanities and community economies in coversation. Austrailian Human Rev 46:145–158 http://australianhumanitiesreview.org/2009/05/01/a-postcapitalist-politics-of-dwelling-ecological-humanities-and-community-economies-in-conversation/

Roseland M (1997) Dimensions of the eco-city. Cities 14(4):197–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0264-2751(97)00003-6

Sarkar AN (2015) Eco-Innovations in Designing Ecocity, Ecotown and Aerotropolis. J Architect Eng Technol 05 (01):1–15. https://doi.org/10.4172/2168-9717.1000161

Article CAS Google Scholar

Scott AJ, Storper M (2015) The Nature of Cities: The Scope and Limits of Urban Theory. Int J Urban Regional Res 39(1):1–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12134

Scriver, P., & Srivastava, A. (2016). Building utopia: 50 years of Auroville. The Architectural Review. https://www.architectural-review.com/essays/building-utopia-50-years-of-auroville

Sen, P. K. (2018). Sri Aurobindo: His Life and Yoga 2nd Harper Collins Publishers India.

Shinn LD (1984) Auroville: Visionary Images and Social Consequences in a South Indian Utopian Community. Religious Stud 20 (2):239–253. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0034412500016024

Smith A (2011) The Transition Town Network: A Review of Current Evolutions and Renaissance. Social Movement Studies 10(1):99–105. https://doi.org/10.1080/14742837.2011.545229

Snow DA, Soule SA, Kriesi H (2004) In: Snow DA, Soule SA, Kriesi H (eds) The Blackwell Companion to Social Movements. Blackwell Publishing Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470999103

Thomas H, Thomas M (2013) Economics for People and Earth - The Auroville Case 1968-2008. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.33040.40967

United Nations. (1987). Our common future: report of the world commission on environment and development 0, 0. https://doi.org/10.1080/07488008808408783

Book Google Scholar

Van Bussel LGJ, De Haan N, Remme RP, Lof ME, De Groot R (2020) Community-based governance: Implications for ecosystem service supply in Berg en Dal, the Netherlands. Ecological Indicators 117(June):106510. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2020.106510

Venkitaraman, A. K. (2017). Addressing Resilience in Transportation in Futurustic Cities: A case of Auroville,Tamil Nadu, India. International Conference on Sustainable Built Environments , 2017. https://aurorepo.in/id/eprint/78/

Waerther S (2014) Sustainability in ecovillages – a reconceptualization. Int J Manage Applied Research 1(1):1–16. https://doi.org/10.18646/2056.11.14-001

Wagner F (2012) Realizing Utopia: Ecovillage Endeavors and Academic Approaches. RCC Perspectives 8 :81–94 http://www.environmentandsociety.org/sites/default/files/ecovillage_research_review_0.pdf

Walsky T, Joshi N (2013) Realizing Utopia : Auroville’s Housing Challenges and the Cost of Sustainability. Abacus 8 (1):1–8 https://aurorepo.in/id/eprint/110/

Wolfram M. (2017). Grassroots Niches in Urban Contexts: Exploring Governance Innovations for Sustainable Development in Seoul. Proc Eng 198, 622–641 (Urban Transitions Conference, Shanghai, September 2016)

Xue J (2014) Is eco-village/urban village the future of a degrowth society? An urban planner’s perspective. Ecol Econ 105:130–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2014.06.003

Download references

Acknowledgements

Code availability.

Code availability is not applicable to this article as no codes were used during the current study.

The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Graduate School of Global Environmental Studies, Kyoto University, Yoshida-Honmachi, Sakyo-ku, Kyoto, 606-8501, Japan

Abhishek Koduvayur Venkitaraman

Leibniz-Institut für ökologische Raumentwicklung (www.ioer.de), Research Area Landscape, Ecosystems and Biodiversity, Weberplatz 1, 01217, Dresden, Germany

Neelakshi Joshi

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Abhishek Koduvayur Venkitaraman .

Ethics declarations

Consent to participate.

Consent to participate is not applicable to this article as no participants were involved.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval is not applicable to this article since the study is based on secondary data.

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Koduvayur Venkitaraman, A., Joshi, N. A critical examination of a community-led ecovillage initiative: a case of Auroville, India. Clim Action 1 , 15 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44168-022-00016-3

Download citation

Received : 29 December 2021

Accepted : 24 June 2022

Published : 08 July 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s44168-022-00016-3

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Global South

This article is cited by

The paradox of collective climate action in rural u.s. ecovillages: ethnographic reflections and perspectives.

- Chelsea Schelly

- Joshua Lockyer

npj Climate Action (2024)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Planning and Development Department

Government of Tamil Nadu

First slide label

Nulla vitae elit libero, a pharetra augue mollis interdum.

Second slide label

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit.

Third slide label

Praesent commodo cursus magna, vel scelerisque nisl consectetur.

Sustainable Development Goals

Working With Department

Knowledge Hub

Data and Performance

- State Statistics

- District Statistics

- Key information on States

- Aspirational Districts statistics

Reports & Publications

- SDG India Index Report

- State Vision 2030 document on SDGs

- Tamil Nadu SDG Annual Status report

- Vision 2023 Tamil Nadu

- Statistical Hand Book

- Policy documents

Special Initiatives

- State Balanced Growth Fund

- Tamil Nadu Innovative Initiatives

- Special Area Development Programme

- Special initiatives of various departments will be shared in this platform.

- Where We Work

Information Note: Tamil Nadu Sustainable Urban Development Project

Construction of tertiary treatment and reverse osmosis plant with capacity of 45 million of leters per day capacity at Koyambedu

The World Bank in May 2019 conducted a mid-term review of the $400-million Tamil Nadu Sustainable Urban Development Project. The Project supports the Government of Tamil Nadu in strengthening the financial and administrative capacity of Urban Local Bodies (ULBs) to plan, finance and deliver services in a financially sustainable manner.

Project Approved: 31-March-2015; Effective: 21-August-2015; Closing: 31-March-2022

Loan Amount: $400 million; Disbursed: 48%

Project Context:

According to the 2011 Census, Tamil Nadu is 48.5 percent urbanized, with about 35 million people living in towns and cities. The Government of Tamil Nadu’s emphasis on the importance of urban development is laid out in its ‘Vision Tamil Nadu 2023’ document, where it seeks to "promote and facilitate the development of inclusive and sustainable cities".

TNSUDP seeks to help the Government of Tamil Nadu (GoTN) put in place a new model for urban management by empowering select municipalities and providing them results-based grants to improve a range of urban services such as water supply, sewerage, drainage, solid waste management, and urban transportation networks. The cities where urban infrastructure is being improved under the Project are Chennai, Theni-Allinagaram, Pammal, Pallavaram, Namakkal, Nagercoil, Sankarankoil, Cuddalore and Thoothukudi.

The cities of Vellore, Erode and Hosur have also been selected for a ‘Model Cities’ pilot where urban management will be improved in four areas: (i) ULB empowerment and organizational capacity; (ii) spatial/development planning; (iii) sustainable finances; and (iv) e-governance and public disclosure.

Implementation is on track and the project development objectives are expected to be achieved by the closing date of 31 March 2022.

In Chennai, the Project is helping improve stormwater drainage to ensure that the city does not suffer as it did during the floods of 2015. Some 407 km of drains and canals are expected to be rehabilitated and upgraded by the end of 2019. The Project is also providing technical assistance for a comprehensive flood warning and control center system for Chennai city. This is scheduled to be completed by October 2020.

An innovative drone-based global information system (GIS) mapping for Chennai is also underway and is scheduled to be completed by March 2020. This mapping will help the city authorities improve urban planning, and facilitate the collection of revenue such as property tax.

With the technical and financial assistance available under the Project, the three Model Cities have increased their own-source revenues, and strengthened the transparency and accountability of the municipal functions in these cities.

Under the e-governance module, a mobile-based interface for citizens called Urban Tree is being developed and will be operational by the end of 2019; this system will allow citizens of these cities to access a range of urban services from their cell phones.

Nearly 100 ULB officers from the Local Fund Audit Department have been trained on audit software in the first phase as part of capacity-building.

Hosur sewerage sub-project will be taken up on a priority basis as all regulatory clearances have now been obtained. While there is an improvement in the management of environmental safeguards for the Project overall, there are pending issues related to the Pallavaram Lakes sub-project in Chennai, including the need to adhere to the disclosed environment management plan, especially with respect to permits for silt disposal. An action plan regarding this is in place.

- My Shodhganga

- Receive email updates

- Edit Profile

Shodhganga : a reservoir of Indian theses @ INFLIBNET

- Shodhganga@INFLIBNET

- Madurai Kamaraj University

- Department of Economics

Items in Shodhganga are licensed under Creative Commons Licence Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0).

Social actors in traditional tank rehabilitation: a case study of Tamil Nadu (India)

- Original Article

- Published: 03 February 2018

- Volume 5 , pages 587–597, ( 2019 )

Cite this article

- Dipankar Roy 1 &

- Shobha Kumari 1

131 Accesses

3 Citations

Explore all metrics

Many conventional participatory resource appraisal projects in India have been criticized for their observed poor standard of equity. Here, the participating community is treated just as a free source of labour, and majority of them do not have any share to the benefits. The Vayalagam Tankfed Agricultural Development Program (VTADP) of the Madurai-based Development of Human Action (DHAN) Foundation is a positive exception to this trail. Apart from the regular technical and institutional aspects of tank management, the program has successfully included the other relevant dimensions of livelihood improvement of the tank communities. It has scaled up the level of equity and sustainability of the said program, and set an alternative example to the government funded tank rehabilitation programs. This paper attempts to explore the various mechanisms of community involvement of the VTADP and assess the nature of changes in community livelihood after the program implementation.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Source: India Micro-irrigation Program Survey, 2011

Source: Farmers’ response during the questionnaire-schedule survey in 2015

Similar content being viewed by others

Religion and Agriculture for Peacebuilding in Rwanda: Analysing the Role of Christian Faith-Based Organisations in the Post-genocide Agrarian Change

Supporting farmer-managed irrigation systems in the Shigar valley, Karakorum: Role of the government and Aga Khan Rural Support Programme

Exclusions in inclusive programs: state-sponsored sustainable development initiatives amongst the kurichya in kerala, india.

Ahluwalia M (1997) Representing communities: the case of a community-based watershed management project in Rajasthan. India IDS Bull 28(4):23–34

Article Google Scholar

Chandrasekaran C, Umashankar V, Jayakumar R (2006)Water users association for sustainable water management: experiences from irrigation sector,Tamil Nadu, India.International Hydrological Programme of UNESCO

Development of Human Action Foundation (2004) Customary rights and their relation to modern tank management in Tamil Nadu, India. Madurai. India

Development of Human Action Foundation (2006) Revisiting mission: annual report 2006. Madurai. India

Development of Human Action Foundation (2007) Encroachment of small scale water bodies: emerging solution for eviction. Policy Brief 1.Madurai. India

Development of Human Action Foundation (2011) Resource mobilization for rehabilitation of tanks with people’s involvement. Policy Brief 9. Madurai. India

Development of Human Action Foundation (2012) Livelihood matter: annual report 2012. Madurai. India

Development of Human Action Foundation (2013) Tank silt application for agricultural production enhancement ___ scope, issues and challenges. Policy Brief 12. Madurai. India

Government of India (2007) Convergence for sustainability: sustainable drinking water supply, sanitation for all 2012. Department of Drinking Water Supply. Ministry of Rural Development. New Delhi

Google Scholar

Government of India (2008) Common Guidelines for Watershed Development Projects. New Delhi

Government of India (2011) Guidelines for Repair, Renovation and Restoration of Water Bodies with Domestic Support.Ministry of Water Resources. New Delhi

Government of Tamil Nadu (2006) AGRISTAT 2006. Directorate of Agriculture. Chennai

Gurunathan A, Shanmugham CR (2006) Customary Rights and their Relevance in Modern Tank Management: Select Cases in Tamil Nadu.Workshop on ‘Water, Law and the Commons’.International Environmental Law Research Centre (IELRC) from 8 to 10 December 2006. New Delhi

Palanisami K, Amarasinghe UA, Sakthivadivel R (2008) Policy Interfacing and Irrigation Development in Tamil Nadu. State Planning Commission. Government of Tamil Nadu. Chennai

Shah M (2013) Water: towards a paradigm shift in the twelfth plan.economic and political weekly.48(3): 40–52

http://wrmin.nic.in/writereaddata/PIM-TN.pdf . Accessed 19 Feb 2015

http://www.ide-india.org/Backend/ModuleFiles/Publication/Files/IMRBReport2012.pdf . Accessed 25 Dec 2014

http://www.tnrd.gov.in/pract/pract_draft.pdf . Accessed 12 Feb 2015

http://www.cseindia.org/userfiles/TN_groundwater_act.pdf . Accessed 11 Mar 2015

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Geography, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, India

Dipankar Roy & Shobha Kumari

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Dipankar Roy .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Roy, D., Kumari, S. Social actors in traditional tank rehabilitation: a case study of Tamil Nadu (India). Sustain. Water Resour. Manag. 5 , 587–597 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40899-018-0221-0

Download citation

Received : 11 May 2017

Accepted : 27 January 2018

Published : 03 February 2018

Issue Date : 01 June 2019

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s40899-018-0221-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Participatory tank management

- Sustainability

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- THE WEEK TV

- ENTERTAINMENT

- WEB STORIES

- JOBS & CAREER

- Home Home -->

- The Week The Week -->

How 'freebies' boosted Tamil Nadu's economy

Growth has been inclusive and individual income has tripled

A 23-year-old domestic help, Rukmani Sukumar feels that her life has improved in the past eight months. A resident of Kannagi Nagar near Chennai, she used to spend around Rs150 a day to commute to work. Now she saves the money, thanks to a government scheme that allows women to travel for free in public buses. “My husband is no more, and there is no support to raise my children,” says Rukmani. “The savings help me buy them books.”

Finance Minister Palanivel Thiaga Rajan said the scheme has “profoundly changed” the lives of employed and college-going women, who make up 40 per cent of bus passengers in the state. “It empowers them to travel without asking anyone’s permission,” he told THE WEEK. “Women’s participation in the economy and social activities outside their homes has profoundly improved. It has had a bigger impact than we thought.”

Welfare schemes and doles have long influenced Tamil Nadu politics. In 1967, when hunger was a major issue, C.N. Annadurai of the DMK became chief minister riding on his promise of ‘One rupee for one padi (litre) rice’. The DMK government soon found out that the promise was expensive and unsustainable, but the welfarism continued.

After he became chief minister in 1977, M.G. Ramachandran of the AIADMK modified an existing mid-day meal scheme to attract children to school. His successors such as M. Karunanidhi of the DMK and J. Jayalalithaa of the AIADMK further polished the scheme, ensuring that more children enrolled in schools. The current DMK government, under Chief Minister M.K. Stalin, has now extended the scheme to include breakfast as well.

“[The measure] could further burden the exchequer, but consider the future. You could ensure demographic dividend by providing meals to schoolchildren,” said S. Janakarajan, former professor at the Madras Institute of Development Studies.

From mid-day meals and free uniforms and sandals, the scope of freebie politics drastically grew in the run-up to the 2006 assembly polls. The DMK came out with a manifesto that promised colour television, cooking-gas connection and stoves for poor households, and free power and loan waivers for farmers and weavers. The manifesto helped the DMK come to power.

Jayalalithaa, who as leader of the opposition had criticised Karunanidhi for using doles to “enslave” voters, also joined the freebie bandwagon in 2011. Her party distributed mixers, grinders and fans, helping her become chief minister. She retained power in 2016 by promising free bicycles, gold for mangalsutras, and subsidised scooters.

Interestingly, despite spending high on freebies and populist schemes, Tamil Nadu has maintained inclusive growth over the decades. Per capita income has gone up from less than Rs20,000 in the late 1960s to Rs60,000 in 2012.

“These 'freebies' are really welfare schemes that are economic necessities to propel inclusive and sustainable growth,” said Prof J. Jeyaranjan, vice chairman of the State Planning Commission.

According to P. Pugazh Gandhi, lawyer and coordinator of the Dravidian Professionals Forum, welfare measures could differ from state to state. “In the desert regions of Rajasthan, it could be drinking water,." he said. "In Kerala, it could be fiscal incentives to encourage entrepreneurs. In Tamil Nadu, it is educational or marriage assistance, and free bus passes to ensure women empowerment. It is up to the legislature or the executive to formulate welfare measures for a particular region.”

- Arvind Kejriwal Gujarat

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Addressing Resilience in Transportation in Futurustic Cities: A case of Auroville,Tamil Nadu, India. International Conference on Sustainable Built Environments , 2017. https://aurorepo.in/id ...

All the three editions of NITI Aayog, the Centre's policy think tank's implementation of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), have one common feature -Tamil Nadu finishing on top with ...

The proposed project will promote access to inclusive, resilient, and sustainable housing and urban development in Tamil Nadu by supporting the state in (i) relocating vulnerable communities living in high-risk areas to safe shelter; (ii) providing affordable, proper housing for urban poor households, and migrant workers from the economically weaker section (EWS) and lower-income group (LIG ...

An intergovernmental set of 17 aspirational Goals with 169 targets, further elaborated through indicators focused on measurable outcomes. SDG is achieving sustainable development in its three dimensions - economic, social and environmental - in a balanced and integrated manner.Several SDG targets are to be achieved before 2030; even by 2020.

Societal Sustainability of Handloom Sector in Tamil Nadu … 163 fabric was from India. USA was the major importer of Indian handloom products in 2018-19 of US$93.34 million followed by the UK, Italy and Germany [6]. 2 Sustainability Issues in the Handloom Industry Handloom products are more eco-friendly, durable and sustainable. Sustainable

Climate risks, emerging threats to humanity, increase the level of disaster in many ways. A comprehensive understanding of climate risks and their impacts is a pre-requisite for developing suitable adaptation strategies toward sustainable development. This paper assessed the socio-economic vulnerability based on sustainable development goals (SDG) in the state of Tamil Nadu in the context of ...

According to the MGNREGS portal, Rajasthan and West Bengal were the other two States which had spent a higher amount of unskilled wages than Tamil Nadu. In the case of the former, the figure was ...

The mission document contains a comprehensive study of climate risks and their impacts based on Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) in the state of Tamil Nadu which showed that Ariyalur is the ...

IND: Inclusive, Resilient and Sustainable Housing for Urban Poor Sector Project in Tamil Nadu Subproject: Construction of 969 Nos of housing units adopting Type Design No. 02/2020 (G+5) with associated ... Strategic Plan for Infrastructure Development in Tamil Nadu." Government of Tamil Nadu. ii residential tenants, 31 absentee owner of a ...

Abstract. Indian handloom sector is one of the age-old cottage industries. The sector provides millions of employments to rural regions of the country either directly or indirectly. This is considered one of the largest employment sectors next to agriculture. Handloom products occupy approximately 40% of the products produced in the Indian market.

2.1. Observed Climate of Tamil Nadu 18 2.2. Projected Climate Change in Tamil Nadu 21 2.3. Impact of Climate Change in various sectors of Tamil Nadu 22 2.4. TN's Greenhouse gas estimates and sustainable economic transition achieving Nation's net zero vision 2.5. Mitigation of Greenhouse Gases in Tamil Nadu 30 2.6.

The project development objective of the Tamil Nadu Sustainable Urban Development Project for India is to improve urban services delivery in participating ULBs in a financially sustainable manner and to pilot improved urban management practices in selected cities. The project is comprised of three components: (i) Results Based Grants for Urban ...

The Project supports the Government of Tamil Nadu in strengthening the financial and administrative capacity of Urban Local Bodies (ULBs) to plan, finance and deliver services in a financially sustainable manner. Project Approved: 31-March-2015; Effective: 21-August-2015; Closing: 31-March-2022. Loan Amount: $400 million; Disbursed: 48%.

Statistical Hand Book of Tamil Nadu-2020-21 637 44.1 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) On 25 September 2015, the Head of Countries and High ... New York adopted the document titled Transforming our world, the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development adopting a new set of global Sustainable Development Goals which will transform the world in ...

for the Tamil Development Department. The Hon'ble Chief Minister has sanctioned an amount of Rs.12.21 crore for the establishment of a world class new site museum at Keeladi. Sustainable Development Goals The Sustainable Development Goals 2030, adopted by the Union Nations and in turn by the Government of India and the Government

The third edition of NITI Aayog's 2020 Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) Index, whose findings were made public in June 2021, placed Tamil Nadu at the second spot.

Sugarcane-based agro-industry in India is spread over 5.2 million hectare and employs around 12 million people. It has immense potential to create shared value for the people, communities, businesses, economies, and ecosystems. This sector is instrumental in positively influencing a number of key Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). This study was performed at Dalmia Bharat Sugar & Industries ...

This research focuses on the urban expansion occurring in the Kamrup Metropolitan District—an area experiencing significant urbanization—with the aim of understanding its patterns and projecting future growth. The research covers the period from 2000 to 2022 and projects growth up to 2052, providing insights for sustainable urban planning. The study utilizes the maximum likelihood method ...

Abstract. Tamil Nadu (TN)'s South-Eastern coastal plain comprises of 5235 villages/wards, is densely populated (∼2000/km 2), and is highly vulnerable to multi-hazard events.Earlier vulnerability case studies carried out in TN utilized district as a unit of analysis, considering mostly the physical parameters.

A Case Study of Tamil Nadu C T Kurien This paper brings together the empirical evidence available on the changes that havei come about in ... In other words, while there has undoubetdly been 'development' in' rural Tamil Nadu, such 'deve. lopment' has only generated growth, and affluence for the few and poverty and insecurity for the many. ...

On April 12, the Tamil Nadu Pollution Control Board (TNPCB) is scheduled to conduct a public hearing for state-owned electricity utility TANGEDCO's proposal to set up the Ennore Thermal Power ...

An economic study of sustainable tourism development with reference to eco tourism in Kodaikanal a tourist hill resort in Tamil nadu: Researcher: N. JEYAKUMAR: Guide(s): R. HARIDOSS: Keywords: An economic study of sustainable tourism A tourist hill resort in Tamil nadu Development with reference to eco tourism: University: Madurai Kamaraj ...

In 2002, a survey was jointly conducted by the UNESCO and Krishi Surya Foundation of Chennai across 30 water user associations (WUAs) formed under the ambitious command area development (CAD) program of the Tamil Nadu Government in the Lower Bhavani basin (Chandrasekaran et al. 2006).The survey did not find any major improvement in the farm livelihoods apart from a 'normal' to 'above ...

Per capita income has gone up from less than Rs20,000 in the late 1960s to Rs60,000 in 2012. "These 'freebies' are really welfare schemes that are economic necessities to propel inclusive and sustainable growth," said Prof J. Jeyaranjan, vice chairman of the State Planning Commission. According to P. Pugazh Gandhi, lawyer and coordinator of ...