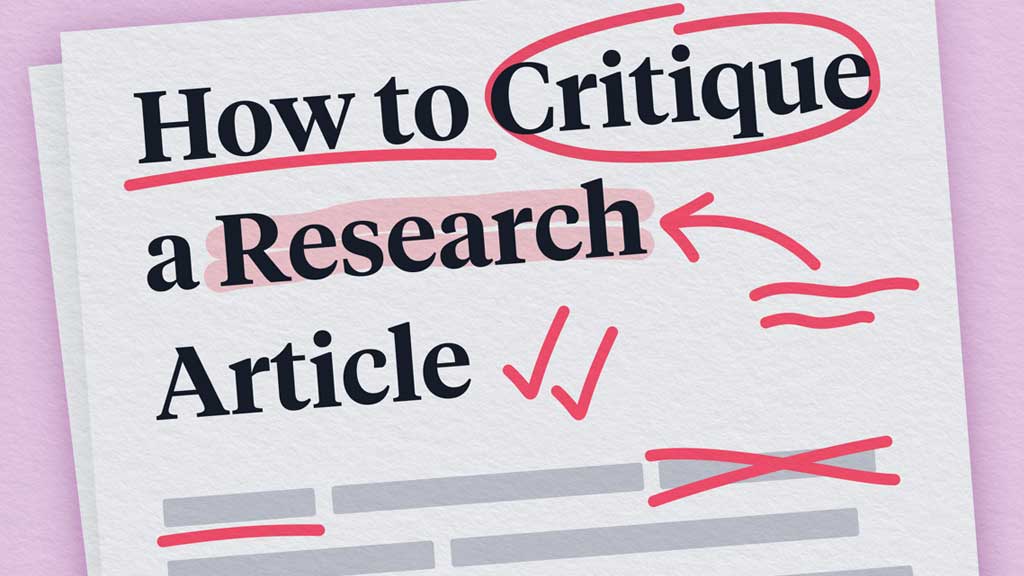

How to Critique a Research Article: A Comprehensive Guide

Learning how to critique a research article is an essential skill for academics, researchers, and professionals in various fields. A research article critique involves carefully analyzing and evaluating a scholarly work to assess its strengths, weaknesses, and overall contribution to the field. By mastering the art of how to critique a research article, you’ll develop critical thinking skills, deepen your understanding of research methodologies, and enhance your ability to contribute meaningfully to academic discussions.

This comprehensive guide will walk you through the process of how to critique a research article effectively. We’ll cover everything from understanding the basics of research articles to providing constructive feedback on complex scientific studies. Whether you’re a student looking to improve your academic writing skills or a professional aiming to stay current in your field, learning how to critique a research article will prove invaluable. By the end of this guide, you’ll have a thorough understanding of the critiquing process and be well-equipped to analyze and evaluate scholarly works with confidence.

What You'll Learn

Understanding the Basics

Before diving into the specifics of how to critique a research article, it’s crucial to understand what a research article is and why critiquing is important. A research article is a scholarly publication that presents original research findings, typically following a standard structure that includes an introduction, methodology, results, and discussion. These articles are the primary means by which researchers communicate their discoveries and contribute to the scientific community.

Learning how to critique a research article is essential for several reasons. First, it helps you develop a critical eye for evaluating the quality and validity of research, which is crucial in an era of information overload. Second, it enhances your understanding of research methodologies and scientific writing, which can improve your own research and writing skills. Lastly, knowing how to critique a research article allows you to engage more deeply with your field of study, enabling you to contribute meaningfully to academic discussions and stay at the forefront of your discipline.

Key components of a research article that you’ll need to focus on when learning how to critique a research article include the title, abstract, introduction, literature review, methodology, results, discussion, conclusion, and references. By systematically examining each of these components, you’ll be able to provide a comprehensive critique of the research article.

Preparing to Critique

Effective preparation is crucial when learning how to critique a research article. The first step in this process is to develop strong reading strategies. As you read the article, focus on understanding the main ideas, research questions, and methodologies used. It’s often helpful to read the article multiple times: first for a general overview, then for a more detailed understanding, and finally for critical analysis.

When learning how to critique a research article, note-taking is an essential skill to develop. As you read, jot down key points, questions, and observations. Consider using a color-coding system to highlight different aspects of the article, such as methodology, results, and conclusions. This will make it easier to reference specific parts of the article when writing your critique.

Another important aspect of how to critique a research article is identifying the article’s main components. Pay close attention to the research question or hypothesis, the theoretical framework, the methodology used, the key findings, and the authors’ interpretations and conclusions. By focusing on these elements, you’ll be better prepared to provide a comprehensive and insightful critique of the research article.

Analyzing the Title and Abstract

When learning how to critique a research article, it’s essential to start with a thorough analysis of the title and abstract. The title of a research article should be clear, concise, and accurately reflect the content of the study. As you critique the title, consider whether it clearly indicates the main topic of the research, is concise yet informative, avoids unnecessary jargon or abbreviations, and accurately represents the scope of the study.

The abstract is a crucial component of any research article, as it provides a brief overview of the entire study. When learning how to critique a research article, pay close attention to the abstract’s completeness and accuracy. A well-written abstract should include the research question or objective, a brief description of the methodology, key findings, and main conclusions.

As you critique the abstract, ask yourself if it provides a clear and concise summary of the study, includes all key elements of the research, accurately represents the content of the full article, and is free from unnecessary details or information not found in the main text. By critically evaluating the title and abstract, you’ll gain valuable insights into the overall quality and focus of the research article, setting the stage for a more in-depth critique of the remaining sections.

Examining the Introduction

When learning how to critique a research article, examining the introduction is crucial. The introduction sets the stage for the entire study and should provide a clear rationale for the research. As you critique this section, focus on evaluating the research question or hypothesis. Ask yourself if the research question is clearly stated and well-defined, if the hypothesis (if present) logically flows from the research question, and if the significance of the study is clearly explained.

Assessing the literature review is another key aspect of how to critique a research article. A strong literature review should provide a comprehensive overview of relevant prior research, identify gaps in existing knowledge, and demonstrate how the current study addresses these gaps. When critiquing the literature review, consider if it’s up-to-date and comprehensive, if it critically analyzes previous studies rather than just summarizing them, and if it clearly shows how the current study builds on or challenges existing research.

Lastly, analyze the theoretical framework presented in the introduction. A well-developed theoretical framework should explain the key concepts and theories underlying the research, show how these concepts relate to the research question, and provide a foundation for interpreting the study’s results. By thoroughly examining these elements of the introduction, you’ll gain valuable insights into the study’s context and purpose, which is essential when learning how to critique a research article effectively.

Scrutinizing the Methodology

A critical part of learning how to critique a research article is scrutinizing the methodology section. This section should provide a detailed description of how the study was conducted, allowing other researchers to replicate the study if desired. When evaluating the research design, consider if the chosen design is appropriate for addressing the research question, if potential limitations of the design are acknowledged and addressed, and if the design is clearly explained and justified.

Assessing data collection methods is another crucial aspect of how to critique a research article. Ask yourself if the methods are clearly described and appropriate for the study, if any instruments or tools used in data collection are validated and reliable, and if potential biases in data collection are acknowledged and mitigated.

Analyzing sampling techniques is also important when learning how to critique a research article. Consider if the sample size is adequate for the study’s goals, if the sampling method is appropriate and clearly described, and if any limitations in the sample are acknowledged.

Lastly, examining ethical considerations is a critical part of how to critique a research article. Look for evidence of informed consent from participants, measures taken to protect participants’ privacy and confidentiality, and approval from relevant ethical review boards. By thoroughly scrutinizing the methodology, you’ll be able to assess the validity and reliability of the study’s findings, which is crucial when learning how to critique a research article effectively.

Evaluating the Results

When learning how to critique a research article, evaluating the results section is crucial. This section should present the findings of the study in a clear, logical manner. Start by assessing the data analysis techniques used. Consider if the statistical methods are appropriate for the type of data collected, if the analyses are clearly explained and justified, and if the researchers have accounted for potential confounding variables.

Interpreting statistical significance is another important aspect of how to critique a research article. Ask yourself if p-values are reported and interpreted correctly, if the significance level is appropriate for the field of study, and if the researchers distinguish between statistical and practical significance.

When evaluating the presentation of findings, consider if the results are presented in a clear, organized manner, if tables and figures are used effectively to illustrate key findings, and if there is a balance between text, tables, and figures. Remember, learning how to critique a research article involves more than just accepting the results at face value. Look for any inconsistencies or unexpected findings, and consider whether these are adequately addressed by the authors. By thoroughly evaluating the results section, you’ll be better equipped to assess the overall validity and impact of the study’s findings.

Critiquing the Discussion and Conclusion

The discussion and conclusion sections are where the authors interpret their findings and place them in the context of existing research. When learning how to critique a research article, pay close attention to how the authors analyze their results. Consider if the interpretations logically follow from the results, if alternative explanations for the findings are considered, and if the discussion is balanced, acknowledging both the strengths and limitations of the study.

Evaluating the discussion of limitations is a crucial part of how to critique a research article. Look for a clear acknowledgment of the study’s limitations, an explanation of how these limitations might affect the interpretation of results, and suggestions for how future research could address these limitations.

Assessing the conclusion’s validity is the final step in learning how to critique a research article. Ask yourself if the conclusion accurately reflects the study’s findings, if the implications of the research are clearly stated, and if there are suggestions for future research that logically follow from the study’s results. Remember, a well-written discussion and conclusion should not only summarize the findings but also place them in a broader context. By critically examining these sections, you’ll gain a deeper understanding of the study’s contribution to the field and its potential impact on future research.

Examining References and Citations

An often overlooked but crucial aspect of learning how to critique a research article is examining the references and citations. The quality and relevance of sources used in a study can significantly impact its credibility and validity. When critiquing references, consider if the sources are recent and relevant to the research topic. Look for a balance between seminal works and current research in the field.

Evaluating the quality of sources is another important step in how to critique a research article. Check if the cited works are from reputable, peer-reviewed journals or respected academic publishers. Be wary of an overreliance on non-academic sources or predatory journals.

Proper citation format is also crucial when learning how to critique a research article. Ensure that all in-text citations are correctly formatted according to the style guide used (e.g., APA, MLA, Chicago). Check if the reference list at the end of the article includes all cited works and follows the correct formatting guidelines.

Lastly, assess the overall depth of research demonstrated by the references. A well-researched article should show a comprehensive understanding of the field, including different perspectives and conflicting findings. By thoroughly examining the references and citations, you’ll gain insights into the authors’ engagement with existing literature and the overall quality of their research foundation.

Writing Your Critique

Once you’ve thoroughly analyzed all aspects of the research article, the next step in learning how to critique a research article is to write your critique. Start by structuring your critique in a logical manner, typically following the same order as the original article (introduction, methodology, results, discussion, conclusion).

When writing your critique, strive for a balance between summary and analysis. While it’s important to briefly summarize the key points of each section, the majority of your critique should focus on your critical analysis and evaluation. Provide constructive feedback, highlighting both the strengths and weaknesses of the study.

A crucial aspect of how to critique a research article is supporting your arguments with evidence. Always refer back to specific parts of the article to justify your critique. Use direct quotes sparingly, and make sure to properly cite them when you do.

Remember that learning how to critique a research article doesn’t mean being overly negative. Acknowledge the positive aspects of the study as well as areas for improvement. Offer suggestions for how the research could be strengthened or expanded in future studies. By providing a balanced, well-supported critique, you’ll demonstrate your understanding of both the specific research and the broader field of study.

Common Pitfalls to Avoid

When learning how to critique a research article, it’s important to be aware of common pitfalls that can undermine the quality of your critique. One frequent mistake is focusing too much on summary rather than analysis. While a brief summary is necessary, the bulk of your critique should be your critical evaluation of the research.

Another pitfall to avoid when learning how to critique a research article is being overly critical or not critical enough. Strive for a balanced approach that acknowledges both the strengths and weaknesses of the study. Remember, even well-conducted research will have limitations, and identifying these is part of the critique process.

Neglecting to provide evidence for your critiques is another common mistake. Always support your arguments with specific examples from the article. This not only strengthens your critique but also demonstrates your thorough engagement with the research.

Lastly, be careful not to misinterpret or misrepresent the original research. This can happen if you don’t fully understand the methodology or statistical analyses used. If you’re unsure about certain aspects of the research, it’s better to acknowledge this than to make incorrect assumptions. By avoiding these common pitfalls, you’ll be well on your way to mastering how to critique a research article effectively.

Enhancing Your Critique Skills

Improving your ability to critique research articles is an ongoing process . One of the best ways to enhance your skills in how to critique a research article is through practice. Try critiquing a variety of research articles from different disciplines and methodological approaches. This will help you become more versatile in your critiquing abilities and expose you to different research paradigms.

Seeking feedback on your critiques is another valuable way to improve your skills. Share your critiques with peers, mentors, or instructors and ask for their input. They may notice aspects you’ve overlooked or provide different perspectives on the research.

Staying updated with research methodologies and trends in your field is crucial when learning how to critique a research article. Attend workshops, webinars, or conferences focused on research methods. Read methodology papers and stay informed about debates and developments in research practices in your discipline.

Finally, consider joining a journal club or research group where you can regularly discuss and critique articles with others. This collaborative approach can significantly enhance your critiquing skills and expose you to different ways of analyzing and evaluating research. Remember, mastering how to critique a research article is a skill that develops over time with practice and continuous learning.

Related Article; A guide for critique of research articles

How do you start a research critique? Start a research critique by thoroughly reading the article, taking notes, and identifying the main components. Begin your critique with a brief summary of the article, followed by your analysis of its strengths and weaknesses, supporting your arguments with evidence from the text.

What are the steps to critiquing a research article? The main steps to critiquing a research article include: reading the article thoroughly, analyzing the title and abstract, examining the introduction and literature review, scrutinizing the methodology, evaluating the results, critiquing the discussion and conclusion, and examining the references and citations.

What are the 5 parts of a critique paper? The five main parts of a critique paper typically include: introduction, summary of the article, critique of the article’s content, evaluation of the article’s contribution to the field, and conclusion.

How do you critically review a research article? To critically review a research article, carefully analyze each section of the paper, evaluate the validity of the methods and results, assess the strength of the arguments and conclusions, and consider the article’s overall contribution to the field.

Start by filling this short order form order.studyinghq.com

And then follow the progressive flow.

Having an issue, chat with us here

Cathy, CS.

New Concept ? Let a subject expert write your paper for You

Post navigation

Previous post.

📕 Studying HQ

Typically replies within minutes

Hey! 👋 Need help with an assignment?

🟢 Online | Privacy policy

WhatsApp us

How to Write an Article Critique Step-by-Step

Table of contents

- 1 What is an Article Critique Writing?

- 2 How to Critique an Article: The Main Steps

- 3 Article Critique Outline

- 4 Article Critique Formatting

- 5 How to Write a Journal Article Critique

- 6 How to Write a Research Article Critique

- 7 Research Methods in Article Critique Writing

- 8 Tips for writing an Article Critique

Do you know how to critique an article? If not, don’t worry – this guide will walk you through the writing process step-by-step. First, we’ll discuss what a research article critique is and its importance. Then, we’ll outline the key points to consider when critiquing a scientific article. Finally, we’ll provide a step-by-step guide on how to write an article critique including introduction, body and summary. Read more to get the main idea of crafting a critique paper.

What is an Article Critique Writing?

An article critique is a formal analysis and evaluation of a piece of writing. It is often written in response to a particular text but can also be a response to a book, a movie, or any other form of writing. There are many different types of review articles . Before writing an article critique, you should have an idea about each of them.

To start writing a good critique, you must first read the article thoroughly and examine and make sure you understand the article’s purpose. Then, you should outline the article’s key points and discuss how well they are presented. Next, you should offer your comments and opinions on the article, discussing whether you agree or disagree with the author’s points and subject. Finally, concluding your critique with a brief summary of your thoughts on the article would be best. Ensure that the general audience understands your perspective on the piece.

How to Critique an Article: The Main Steps

If you are wondering “what is included in an article critique,” the answer is:

An article critique typically includes the following:

- A brief summary of the article .

- A critical evaluation of the article’s strengths and weaknesses.

- A conclusion.

When critiquing an article, it is essential to critically read the piece and consider the author’s purpose and research strategies that the author chose. Next, provide a brief summary of the text, highlighting the author’s main points and ideas. Critique an article using formal language and relevant literature in the body paragraphs. Finally, describe the thesis statement, main idea, and author’s interpretations in your language using specific examples from the article. It is also vital to discuss the statistical methods used and whether they are appropriate for the research question. Make notes of the points you think need to be discussed, and also do a literature review from where the author ground their research. Offer your perspective on the article and whether it is well-written. Finally, provide background information on the topic if necessary.

When you are reading an article, it is vital to take notes and critique the text to understand it fully and to be able to use the information in it. Here are the main steps for critiquing an article:

- Read the piece thoroughly, taking notes as you go. Ensure you understand the main points and the author’s argument.

- Take a look at the author’s perspective. Is it powerful? Does it back up the author’s point of view?

- Carefully examine the article’s tone. Is it biased? Are you being persuaded by the author in any way?

- Look at the structure. Is it well organized? Does it make sense?

- Consider the writing style. Is it clear? Is it well-written?

- Evaluate the sources the author uses. Are they credible?

- Think about your own opinion. With what do you concur or disagree? Why?

Article Critique Outline

When assigned an article critique, your instructor asks you to read and analyze it and provide feedback. A specific format is typically followed when writing an article critique.

An article critique usually has three sections: an introduction, a body, and a conclusion.

- The introduction of your article critique should have a summary and key points.

- The critique’s main body should thoroughly evaluate the piece, highlighting its strengths and weaknesses, and state your ideas and opinions with supporting evidence.

- The conclusion should restate your research and describe your opinion.

You should provide your analysis rather than simply agreeing or disagreeing with the author. When writing an article review , it is essential to be objective and critical. Describe your perspective on the subject and create an article review summary. Be sure to use proper grammar, spelling, and punctuation, write it in the third person, and cite your sources.

Article Critique Formatting

When writing an article critique, you should follow a few formatting guidelines. The importance of using a proper format is to make your review clear and easy to read.

Make sure to use double spacing throughout your critique. It will make it easy to understand and read for your instructor.

Indent each new paragraph. It will help to separate your critique into different sections visually.

Use headings to organize your critique. Your introduction, body, and conclusion should stand out. It will make it easy for your instructor to follow your thoughts.

Use standard fonts, such as Times New Roman or Arial. It will make your critique easy to read.

Use 12-point font size. It will ensure that your critique is easy to read.

How to Write a Journal Article Critique

When critiquing a journal article, there are a few key points to keep in mind:

- Good critiques should be objective, meaning that the author’s ideas and arguments should be evaluated without personal bias.

- Critiques should be critical, meaning that all aspects of the article should be examined, including the author’s introduction, main ideas, and discussion.

- Critiques should be informative, providing the reader with a clear understanding of the article’s strengths and weaknesses.

When critiquing a research article, evaluating the author’s argument and the evidence they present is important. The author should state their thesis or the main point in the introductory paragraph. You should explain the article’s main ideas and evaluate the evidence critically. In the discussion section, the author should explain the implications of their findings and suggest future research.

It is also essential to keep a critical eye when reading scientific articles. In order to be credible, the scientific article must be based on evidence and previous literature. The author’s argument should be well-supported by data and logical reasoning.

How to Write a Research Article Critique

When you are assigned a research article, the first thing you need to do is read the piece carefully. Make sure you understand the subject matter and the author’s chosen approach. Next, you need to assess the importance of the author’s work. What are the key findings, and how do they contribute to the field of research?

Finally, you need to provide a critical point-by-point analysis of the article. This should include discussing the research questions, the main findings, and the overall impression of the scientific piece. In conclusion, you should state whether the text is good or bad. Read more to get an idea about curating a research article critique. But if you are not confident, you can ask “ write my papers ” and hire a professional to craft a critique paper for you. Explore your options online and get high-quality work quickly.

However, test yourself and use the following tips to write a research article critique that is clear, concise, and properly formatted.

- Take notes while you read the text in its entirety. Right down each point you agree and disagree with.

- Write a thesis statement that concisely and clearly outlines the main points.

- Write a paragraph that introduces the article and provides context for the critique.

- Write a paragraph for each of the following points, summarizing the main points and providing your own analysis:

- The purpose of the study

- The research question or questions

- The methods used

- The outcomes

- The conclusions were drawn by the author(s)

- Mention the strengths and weaknesses of the piece in a separate paragraph.

- Write a conclusion that summarizes your thoughts about the article.

- Free unlimited checks

- All common file formats

- Accurate results

- Intuitive interface

Research Methods in Article Critique Writing

When writing an article critique, it is important to use research methods to support your arguments. There are a variety of research methods that you can use, and each has its strengths and weaknesses. In this text, we will discuss four of the most common research methods used in article critique writing: quantitative research, qualitative research, systematic reviews, and meta-analysis.

Quantitative research is a research method that uses numbers and statistics to analyze data. This type of research is used to test hypotheses or measure a treatment’s effects. Quantitative research is normally considered more reliable than qualitative research because it considers a large amount of information. But, it might be difficult to find enough data to complete it properly.

Qualitative research is a research method that uses words and interviews to analyze data. This type of research is used to understand people’s thoughts and feelings. Qualitative research is usually more reliable than quantitative research because it is less likely to be biased. Though it is more expensive and tedious.

Systematic reviews are a type of research that uses a set of rules to search for and analyze studies on a particular topic. Some think that systematic reviews are more reliable than other research methods because they use a rigorous process to find and analyze studies. However, they can be pricy and long to carry out.

Meta-analysis is a type of research that combines several studies’ results to understand a treatment’s overall effect better. Meta-analysis is generally considered one of the most reliable type of research because it uses data from several approved studies. Conversely, it involves a long and costly process.

Are you still struggling to understand the critique of an article concept? You can contact an online review writing service to get help from skilled writers. You can get custom, and unique article reviews easily.

Tips for writing an Article Critique

It’s crucial to keep in mind that you’re not just sharing your opinion of the content when you write an article critique. Instead, you are providing a critical analysis, looking at its strengths and weaknesses. In order to write a compelling critique, you should follow these tips: Take note carefully of the essential elements as you read it.

- Make sure that you understand the thesis statement.

- Write down your thoughts, including strengths and weaknesses.

- Use evidence from to support your points.

- Create a clear and concise critique, making sure to avoid giving your opinion.

It is important to be clear and concise when creating an article critique. You should avoid giving your opinion and instead focus on providing a critical analysis. You should also use evidence from the article to support your points.

Readers also enjoyed

WHY WAIT? PLACE AN ORDER RIGHT NOW!

Just fill out the form, press the button, and have no worries!

We use cookies to give you the best experience possible. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy.

- All eBooks & Audiobooks

- Academic eBook Collection

- Home Grown eBook Collection

- Off-Campus Access

- Literature Resource Center

- Opposing Viewpoints

- ProQuest Central

- Course Guides

- Citing Sources

- Library Research

- Websites by Topic

- Book-a-Librarian

- Research Tutorials

- Use the Catalog

- Use Databases

- Use Films on Demand

- Use Home Grown eBooks

- Use NC LIVE

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary vs. Secondary

- Scholarly vs. Popular

- Make an Appointment

- Writing Tools

- Annotated Bibliographies

- Summaries, Reviews & Critiques

- Writing Center

Service Alert

Article Summaries, Reviews & Critiques

- Writing an article SUMMARY

- Writing an article REVIEW

Writing an article CRITIQUE

- Citing Sources This link opens in a new window

- About RCC Library

Text: 336-308-8801

Email: [email protected]

Call: 336-633-0204

Schedule: Book-a-Librarian

Like us on Facebook

Links on this guide may go to external web sites not connected with Randolph Community College. Their inclusion is not an endorsement by Randolph Community College and the College is not responsible for the accuracy of their content or the security of their site.

A critique asks you to evaluate an article and the author’s argument. You will need to look critically at what the author is claiming, evaluate the research methods, and look for possible problems with, or applications of, the researcher’s claims.

Introduction

Give an overview of the author’s main points and how the author supports those points. Explain what the author found and describe the process they used to arrive at this conclusion.

Body Paragraphs

Interpret the information from the article:

- Does the author review previous studies? Is current and relevant research used?

- What type of research was used – empirical studies, anecdotal material, or personal observations?

- Was the sample too small to generalize from?

- Was the participant group lacking in diversity (race, gender, age, education, socioeconomic status, etc.)

- For instance, volunteers gathered at a health food store might have different attitudes about nutrition than the population at large.

- How useful does this work seem to you? How does the author suggest the findings could be applied and how do you believe they could be applied?

- How could the study have been improved in your opinion?

- Does the author appear to have any biases (related to gender, race, class, or politics)?

- Is the writing clear and easy to follow? Does the author’s tone add to or detract from the article?

- How useful are the visuals (such as tables, charts, maps, photographs) included, if any? How do they help to illustrate the argument? Are they confusing or hard to read?

- What further research might be conducted on this subject?

Try to synthesize the pieces of your critique to emphasize your own main points about the author’s work, relating the researcher’s work to your own knowledge or to topics being discussed in your course.

From the Center for Academic Excellence (opens in a new window), University of Saint Joseph Connecticut

Additional Resources

All links open in a new window.

Writing an Article Critique (from The University of Arizona Global Campus Writing Center)

How to Critique an Article (from Essaypro.com)

How to Write an Article Critique (from EliteEditing.com.au)

- << Previous: Writing an article REVIEW

- Next: Citing Sources >>

- Last Updated: Mar 15, 2024 9:32 AM

- URL: https://libguides.randolph.edu/summaries

You are using an outdated browser

Unfortunately Ausmed.com does not support your browser. Please upgrade your browser to continue.

How to Critique a Research Article

Let's briefly examine some basic pointers on how to perform a literature review.

If you've managed to get your hands on peer-reviewed articles, then you may wonder why it is necessary for you to perform your own article critique. Surely the article will be of good quality if it has made it through the peer-review process?

Unfortunately, this is not always the case.

Publication bias can occur when editors only accept manuscripts that have a bearing on the direction of their own research, or reject manuscripts with negative findings. Additionally, not all peer reviewers have expert knowledge on certain subject matters , which can introduce bias and sometimes a conflict of interest.

Performing your own critical analysis of an article allows you to consider its value to you and to your workplace.

Critical evaluation is defined as a systematic way of considering the truthfulness of a piece of research, its results and how relevant and applicable they are.

How to Critique

It can be a little overwhelming trying to critique an article when you're not sure where to start. Considering the article under the following headings may be of some use:

Title of Study/Research

You may be a better judge of this after reading the article, but the title should succinctly reflect the content of the work, stimulating readers' interest.

Three to six keywords that encapsulate the main topics of the research will have been drawn from the body of the article.

Introduction

This should include:

- Evidence of a literature review that is relevant and recent, critically appraising other works rather than merely describing them

- Background information on the study to orientate the reader to the problem

- Hypothesis or aims of the study

- Rationale for the study that justifies its need, i.e. to explore an un-investigated gap in the literature.

Materials and Methods

Similar to a recipe, the description of materials and methods will allow others to replicate the study elsewhere if needed. It should both contain and justify the exact specifications of selection criteria, sample size, response rate and any statistics used. This will demonstrate how the study is capable of achieving its aims. Things to consider in this section are:

- What sort of sampling technique and size was used?

- What proportion of the eligible sample participated? (e.g. '553 responded to a survey sent to 750 medical technologists'

- Were all eligible groups sampled? (e.g. was the survey sent only in English?)

- What were the strengths and weaknesses of the study?

- Were there threats to the reliability and validity of the study, and were these controlled for?

- Were there any obvious biases?

- If a trial was undertaken, was it randomised, case-controlled, blinded or double-blinded?

Results should be statistically analysed and presented in a way that an average reader of the journal will understand. Graphs and tables should be clear and promote clarity of the text. Consider whether:

- There were any major omissions in the results, which could indicate bias

- Percentages have been used to disguise small sample sizes

- The data generated is consistent with the data collected.

Negative results are just as relevant as research that produces positive results (but, as mentioned previously, may be omitted in publication due to editorial bias).

This should show insight into the meaning and significance of the research findings. It should not introduce any new material but should address how the aims of the study have been met. The discussion should use previous research work and theoretical concepts as the context in which the new study can be interpreted. Any limitations of the study, including bias, should be clearly presented. You will need to evaluate whether the author has clearly interpreted the results of the study, or whether the results could be interpreted another way.

Conclusions

These should be clearly stated and will only be valid if the study was reliable, valid and used a representative sample size. There may also be recommendations for further research.

These should be relevant to the study, be up-to-date, and should provide a comprehensive list of citations within the text.

Final Thoughts

Undertaking a critique of a research article may seem challenging at first, but will help you to evaluate whether the article has relevance to your own practice and workplace. Reading a single article can act as a springboard into researching the topic more widely, and aids in ensuring your nursing practice remains current and is supported by existing literature.

- Marshall, G 2005, ‘Critiquing a Research Article’, Radiography , vol. 11, no. 1, viewed 2 October 2023, https://www.radiographyonline.com/article/S1078-8174(04)00119-1/fulltext

Assign mandatory training and keep all your records in-one-place.

Help and Feedback

Ausmed Education is a Trusted Information Partner of Healthdirect Australia. Verify here .

Making sense of research: A guide for critiquing a paper

Affiliation.

- 1 School of Nursing, Griffith University, Meadowbrook, Queensland.

- PMID: 16114192

- DOI: 10.5172/conu.14.1.38

Learning how to critique research articles is one of the fundamental skills of scholarship in any discipline. The range, quantity and quality of publications available today via print, electronic and Internet databases means it has become essential to equip students and practitioners with the prerequisites to judge the integrity and usefulness of published research. Finding, understanding and critiquing quality articles can be a difficult process. This article sets out some helpful indicators to assist the novice to make sense of research.

Publication types

- Data Interpretation, Statistical

- Research Design

- Review Literature as Topic

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Ten Simple Rules for Writing a Literature Review

Marco pautasso.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

* E-mail: [email protected]

The author has declared that no competing interests exist.

Collection date 2013 Jul.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are properly credited.

Literature reviews are in great demand in most scientific fields. Their need stems from the ever-increasing output of scientific publications [1] . For example, compared to 1991, in 2008 three, eight, and forty times more papers were indexed in Web of Science on malaria, obesity, and biodiversity, respectively [2] . Given such mountains of papers, scientists cannot be expected to examine in detail every single new paper relevant to their interests [3] . Thus, it is both advantageous and necessary to rely on regular summaries of the recent literature. Although recognition for scientists mainly comes from primary research, timely literature reviews can lead to new synthetic insights and are often widely read [4] . For such summaries to be useful, however, they need to be compiled in a professional way [5] .

When starting from scratch, reviewing the literature can require a titanic amount of work. That is why researchers who have spent their career working on a certain research issue are in a perfect position to review that literature. Some graduate schools are now offering courses in reviewing the literature, given that most research students start their project by producing an overview of what has already been done on their research issue [6] . However, it is likely that most scientists have not thought in detail about how to approach and carry out a literature review.

Reviewing the literature requires the ability to juggle multiple tasks, from finding and evaluating relevant material to synthesising information from various sources, from critical thinking to paraphrasing, evaluating, and citation skills [7] . In this contribution, I share ten simple rules I learned working on about 25 literature reviews as a PhD and postdoctoral student. Ideas and insights also come from discussions with coauthors and colleagues, as well as feedback from reviewers and editors.

Rule 1: Define a Topic and Audience

How to choose which topic to review? There are so many issues in contemporary science that you could spend a lifetime of attending conferences and reading the literature just pondering what to review. On the one hand, if you take several years to choose, several other people may have had the same idea in the meantime. On the other hand, only a well-considered topic is likely to lead to a brilliant literature review [8] . The topic must at least be:

interesting to you (ideally, you should have come across a series of recent papers related to your line of work that call for a critical summary),

an important aspect of the field (so that many readers will be interested in the review and there will be enough material to write it), and

a well-defined issue (otherwise you could potentially include thousands of publications, which would make the review unhelpful).

Ideas for potential reviews may come from papers providing lists of key research questions to be answered [9] , but also from serendipitous moments during desultory reading and discussions. In addition to choosing your topic, you should also select a target audience. In many cases, the topic (e.g., web services in computational biology) will automatically define an audience (e.g., computational biologists), but that same topic may also be of interest to neighbouring fields (e.g., computer science, biology, etc.).

Rule 2: Search and Re-search the Literature

After having chosen your topic and audience, start by checking the literature and downloading relevant papers. Five pieces of advice here:

keep track of the search items you use (so that your search can be replicated [10] ),

keep a list of papers whose pdfs you cannot access immediately (so as to retrieve them later with alternative strategies),

use a paper management system (e.g., Mendeley, Papers, Qiqqa, Sente),

define early in the process some criteria for exclusion of irrelevant papers (these criteria can then be described in the review to help define its scope), and

do not just look for research papers in the area you wish to review, but also seek previous reviews.

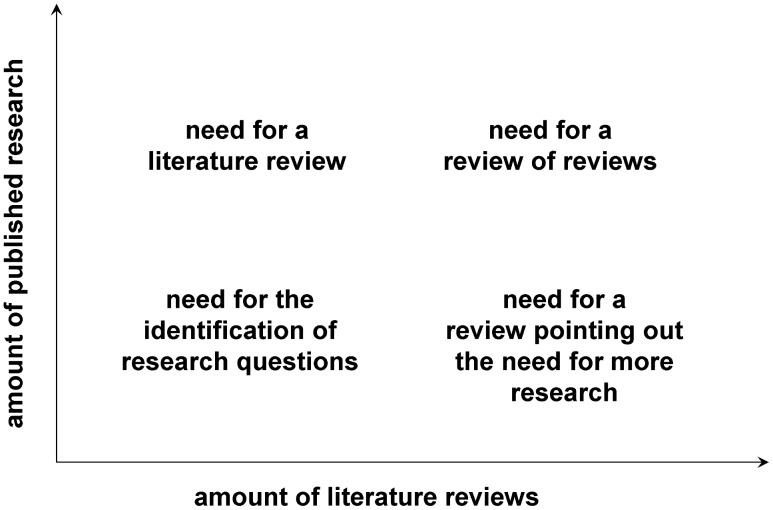

The chances are high that someone will already have published a literature review ( Figure 1 ), if not exactly on the issue you are planning to tackle, at least on a related topic. If there are already a few or several reviews of the literature on your issue, my advice is not to give up, but to carry on with your own literature review,

Figure 1. A conceptual diagram of the need for different types of literature reviews depending on the amount of published research papers and literature reviews.

The bottom-right situation (many literature reviews but few research papers) is not just a theoretical situation; it applies, for example, to the study of the impacts of climate change on plant diseases, where there appear to be more literature reviews than research studies [33] .

discussing in your review the approaches, limitations, and conclusions of past reviews,

trying to find a new angle that has not been covered adequately in the previous reviews, and

incorporating new material that has inevitably accumulated since their appearance.

When searching the literature for pertinent papers and reviews, the usual rules apply:

be thorough,

use different keywords and database sources (e.g., DBLP, Google Scholar, ISI Proceedings, JSTOR Search, Medline, Scopus, Web of Science), and

look at who has cited past relevant papers and book chapters.

Rule 3: Take Notes While Reading

If you read the papers first, and only afterwards start writing the review, you will need a very good memory to remember who wrote what, and what your impressions and associations were while reading each single paper. My advice is, while reading, to start writing down interesting pieces of information, insights about how to organize the review, and thoughts on what to write. This way, by the time you have read the literature you selected, you will already have a rough draft of the review.

Of course, this draft will still need much rewriting, restructuring, and rethinking to obtain a text with a coherent argument [11] , but you will have avoided the danger posed by staring at a blank document. Be careful when taking notes to use quotation marks if you are provisionally copying verbatim from the literature. It is advisable then to reformulate such quotes with your own words in the final draft. It is important to be careful in noting the references already at this stage, so as to avoid misattributions. Using referencing software from the very beginning of your endeavour will save you time.

Rule 4: Choose the Type of Review You Wish to Write

After having taken notes while reading the literature, you will have a rough idea of the amount of material available for the review. This is probably a good time to decide whether to go for a mini- or a full review. Some journals are now favouring the publication of rather short reviews focusing on the last few years, with a limit on the number of words and citations. A mini-review is not necessarily a minor review: it may well attract more attention from busy readers, although it will inevitably simplify some issues and leave out some relevant material due to space limitations. A full review will have the advantage of more freedom to cover in detail the complexities of a particular scientific development, but may then be left in the pile of the very important papers “to be read” by readers with little time to spare for major monographs.

There is probably a continuum between mini- and full reviews. The same point applies to the dichotomy of descriptive vs. integrative reviews. While descriptive reviews focus on the methodology, findings, and interpretation of each reviewed study, integrative reviews attempt to find common ideas and concepts from the reviewed material [12] . A similar distinction exists between narrative and systematic reviews: while narrative reviews are qualitative, systematic reviews attempt to test a hypothesis based on the published evidence, which is gathered using a predefined protocol to reduce bias [13] , [14] . When systematic reviews analyse quantitative results in a quantitative way, they become meta-analyses. The choice between different review types will have to be made on a case-by-case basis, depending not just on the nature of the material found and the preferences of the target journal(s), but also on the time available to write the review and the number of coauthors [15] .

Rule 5: Keep the Review Focused, but Make It of Broad Interest

Whether your plan is to write a mini- or a full review, it is good advice to keep it focused 16 , 17 . Including material just for the sake of it can easily lead to reviews that are trying to do too many things at once. The need to keep a review focused can be problematic for interdisciplinary reviews, where the aim is to bridge the gap between fields [18] . If you are writing a review on, for example, how epidemiological approaches are used in modelling the spread of ideas, you may be inclined to include material from both parent fields, epidemiology and the study of cultural diffusion. This may be necessary to some extent, but in this case a focused review would only deal in detail with those studies at the interface between epidemiology and the spread of ideas.

While focus is an important feature of a successful review, this requirement has to be balanced with the need to make the review relevant to a broad audience. This square may be circled by discussing the wider implications of the reviewed topic for other disciplines.

Rule 6: Be Critical and Consistent

Reviewing the literature is not stamp collecting. A good review does not just summarize the literature, but discusses it critically, identifies methodological problems, and points out research gaps [19] . After having read a review of the literature, a reader should have a rough idea of:

the major achievements in the reviewed field,

the main areas of debate, and

the outstanding research questions.

It is challenging to achieve a successful review on all these fronts. A solution can be to involve a set of complementary coauthors: some people are excellent at mapping what has been achieved, some others are very good at identifying dark clouds on the horizon, and some have instead a knack at predicting where solutions are going to come from. If your journal club has exactly this sort of team, then you should definitely write a review of the literature! In addition to critical thinking, a literature review needs consistency, for example in the choice of passive vs. active voice and present vs. past tense.

Rule 7: Find a Logical Structure

Like a well-baked cake, a good review has a number of telling features: it is worth the reader's time, timely, systematic, well written, focused, and critical. It also needs a good structure. With reviews, the usual subdivision of research papers into introduction, methods, results, and discussion does not work or is rarely used. However, a general introduction of the context and, toward the end, a recapitulation of the main points covered and take-home messages make sense also in the case of reviews. For systematic reviews, there is a trend towards including information about how the literature was searched (database, keywords, time limits) [20] .

How can you organize the flow of the main body of the review so that the reader will be drawn into and guided through it? It is generally helpful to draw a conceptual scheme of the review, e.g., with mind-mapping techniques. Such diagrams can help recognize a logical way to order and link the various sections of a review [21] . This is the case not just at the writing stage, but also for readers if the diagram is included in the review as a figure. A careful selection of diagrams and figures relevant to the reviewed topic can be very helpful to structure the text too [22] .

Rule 8: Make Use of Feedback

Reviews of the literature are normally peer-reviewed in the same way as research papers, and rightly so [23] . As a rule, incorporating feedback from reviewers greatly helps improve a review draft. Having read the review with a fresh mind, reviewers may spot inaccuracies, inconsistencies, and ambiguities that had not been noticed by the writers due to rereading the typescript too many times. It is however advisable to reread the draft one more time before submission, as a last-minute correction of typos, leaps, and muddled sentences may enable the reviewers to focus on providing advice on the content rather than the form.

Feedback is vital to writing a good review, and should be sought from a variety of colleagues, so as to obtain a diversity of views on the draft. This may lead in some cases to conflicting views on the merits of the paper, and on how to improve it, but such a situation is better than the absence of feedback. A diversity of feedback perspectives on a literature review can help identify where the consensus view stands in the landscape of the current scientific understanding of an issue [24] .

Rule 9: Include Your Own Relevant Research, but Be Objective

In many cases, reviewers of the literature will have published studies relevant to the review they are writing. This could create a conflict of interest: how can reviewers report objectively on their own work [25] ? Some scientists may be overly enthusiastic about what they have published, and thus risk giving too much importance to their own findings in the review. However, bias could also occur in the other direction: some scientists may be unduly dismissive of their own achievements, so that they will tend to downplay their contribution (if any) to a field when reviewing it.

In general, a review of the literature should neither be a public relations brochure nor an exercise in competitive self-denial. If a reviewer is up to the job of producing a well-organized and methodical review, which flows well and provides a service to the readership, then it should be possible to be objective in reviewing one's own relevant findings. In reviews written by multiple authors, this may be achieved by assigning the review of the results of a coauthor to different coauthors.

Rule 10: Be Up-to-Date, but Do Not Forget Older Studies

Given the progressive acceleration in the publication of scientific papers, today's reviews of the literature need awareness not just of the overall direction and achievements of a field of inquiry, but also of the latest studies, so as not to become out-of-date before they have been published. Ideally, a literature review should not identify as a major research gap an issue that has just been addressed in a series of papers in press (the same applies, of course, to older, overlooked studies (“sleeping beauties” [26] )). This implies that literature reviewers would do well to keep an eye on electronic lists of papers in press, given that it can take months before these appear in scientific databases. Some reviews declare that they have scanned the literature up to a certain point in time, but given that peer review can be a rather lengthy process, a full search for newly appeared literature at the revision stage may be worthwhile. Assessing the contribution of papers that have just appeared is particularly challenging, because there is little perspective with which to gauge their significance and impact on further research and society.

Inevitably, new papers on the reviewed topic (including independently written literature reviews) will appear from all quarters after the review has been published, so that there may soon be the need for an updated review. But this is the nature of science [27] – [32] . I wish everybody good luck with writing a review of the literature.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to M. Barbosa, K. Dehnen-Schmutz, T. Döring, D. Fontaneto, M. Garbelotto, O. Holdenrieder, M. Jeger, D. Lonsdale, A. MacLeod, P. Mills, M. Moslonka-Lefebvre, G. Stancanelli, P. Weisberg, and X. Xu for insights and discussions, and to P. Bourne, T. Matoni, and D. Smith for helpful comments on a previous draft.

Funding Statement

This work was funded by the French Foundation for Research on Biodiversity (FRB) through its Centre for Synthesis and Analysis of Biodiversity data (CESAB), as part of the NETSEED research project. The funders had no role in the preparation of the manuscript.

- 1. Rapple C (2011) The role of the critical review article in alleviating information overload. Annual Reviews White Paper. Available: http://www.annualreviews.org/userimages/ContentEditor/1300384004941/Annual_Reviews_WhitePaper_Web_2011.pdf . Accessed May 2013.

- 2. Pautasso M (2010) Worsening file-drawer problem in the abstracts of natural, medical and social science databases. Scientometrics 85: 193–202 doi: 10.1007/s11192-010-0233-5 [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. Erren TC, Cullen P, Erren M (2009) How to surf today's information tsunami: on the craft of effective reading. Med Hypotheses 73: 278–279 doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2009.05.002 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 4. Hampton SE, Parker JN (2011) Collaboration and productivity in scientific synthesis. Bioscience 61: 900–910 doi: 10.1525/bio.2011.61.11.9 [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. Ketcham CM, Crawford JM (2007) The impact of review articles. Lab Invest 87: 1174–1185 doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700688 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. Boote DN, Beile P (2005) Scholars before researchers: on the centrality of the dissertation literature review in research preparation. Educ Res 34: 3–15 doi: 10.3102/0013189X034006003 [ Google Scholar ]

- 7. Budgen D, Brereton P (2006) Performing systematic literature reviews in software engineering. Proc 28th Int Conf Software Engineering, ACM New York, NY, USA, pp. 1051–1052. doi: 10.1145/1134285.1134500 .

- 8. Maier HR (2013) What constitutes a good literature review and why does its quality matter? Environ Model Softw 43: 3–4 doi: 10.1016/j.envsoft.2013.02.004 [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. Sutherland WJ, Fleishman E, Mascia MB, Pretty J, Rudd MA (2011) Methods for collaboratively identifying research priorities and emerging issues in science and policy. Methods Ecol Evol 2: 238–247 doi: 10.1111/j.2041-210X.2010.00083.x [ Google Scholar ]

- 10. Maggio LA, Tannery NH, Kanter SL (2011) Reproducibility of literature search reporting in medical education reviews. Acad Med 86: 1049–1054 doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31822221e7 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 11. Torraco RJ (2005) Writing integrative literature reviews: guidelines and examples. Human Res Develop Rev 4: 356–367 doi: 10.1177/1534484305278283 [ Google Scholar ]

- 12. Khoo CSG, Na JC, Jaidka K (2011) Analysis of the macro-level discourse structure of literature reviews. Online Info Rev 35: 255–271 doi: 10.1108/14684521111128032 [ Google Scholar ]

- 13. Rosenfeld RM (1996) How to systematically review the medical literature. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 115: 53–63 doi: 10.1016/S0194-5998(96)70137-7 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 14. Cook DA, West CP (2012) Conducting systematic reviews in medical education: a stepwise approach. Med Educ 46: 943–952 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2012.04328.x [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 15. Dijkers M (2009) The Task Force on Systematic Reviews and Guidelines (2009) The value of “traditional” reviews in the era of systematic reviewing. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 88: 423–430 doi: 10.1097/PHM.0b013e31819c59c6 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 16. Eco U (1977) Come si fa una tesi di laurea. Milan: Bompiani.

- 17. Hart C (1998) Doing a literature review: releasing the social science research imagination. London: SAGE.

- 18. Wagner CS, Roessner JD, Bobb K, Klein JT, Boyack KW, et al. (2011) Approaches to understanding and measuring interdisciplinary scientific research (IDR): a review of the literature. J Informetr 5: 14–26 doi: 10.1016/j.joi.2010.06.004 [ Google Scholar ]

- 19. Carnwell R, Daly W (2001) Strategies for the construction of a critical review of the literature. Nurse Educ Pract 1: 57–63 doi: 10.1054/nepr.2001.0008 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 20. Roberts PD, Stewart GB, Pullin AS (2006) Are review articles a reliable source of evidence to support conservation and environmental management? A comparison with medicine. Biol Conserv 132: 409–423 doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2006.04.034 [ Google Scholar ]

- 21. Ridley D (2008) The literature review: a step-by-step guide for students. London: SAGE.

- 22. Kelleher C, Wagener T (2011) Ten guidelines for effective data visualization in scientific publications. Environ Model Softw 26: 822–827 doi: 10.1016/j.envsoft.2010.12.006 [ Google Scholar ]

- 23. Oxman AD, Guyatt GH (1988) Guidelines for reading literature reviews. CMAJ 138: 697–703. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 24. May RM (2011) Science as organized scepticism. Philos Trans A Math Phys Eng Sci 369: 4685–4689 doi: 10.1098/rsta.2011.0177 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 25. Logan DW, Sandal M, Gardner PP, Manske M, Bateman A (2010) Ten simple rules for editing Wikipedia. PLoS Comput Biol 6: e1000941 doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000941 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 26. van Raan AFJ (2004) Sleeping beauties in science. Scientometrics 59: 467–472 doi: 10.1023/B:SCIE.0000018543.82441.f1 [ Google Scholar ]

- 27. Rosenberg D (2003) Early modern information overload. J Hist Ideas 64: 1–9 doi: 10.1353/jhi.2003.0017 [ Google Scholar ]

- 28. Bastian H, Glasziou P, Chalmers I (2010) Seventy-five trials and eleven systematic reviews a day: how will we ever keep up? PLoS Med 7: e1000326 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000326 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 29. Bertamini M, Munafò MR (2012) Bite-size science and its undesired side effects. Perspect Psychol Sci 7: 67–71 doi: 10.1177/1745691611429353 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 30. Pautasso M (2012) Publication growth in biological sub-fields: patterns, predictability and sustainability. Sustainability 4: 3234–3247 doi: 10.3390/su4123234 [ Google Scholar ]

- 31. Michels C, Schmoch U (2013) Impact of bibliometric studies on the publication behaviour of authors. Scientometrics doi: 10.1007/s11192-013-1015-7. In press. [ Google Scholar ]

- 32. Tsafnat G, Dunn A, Glasziou P, Coiera E (2013) The automation of systematic reviews. BMJ 346: f139 doi: 10.1136/bmj.f139 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 33. Pautasso M, Döring TF, Garbelotto M, Pellis L, Jeger MJ (2012) Impacts of climate change on plant diseases - opinions and trends. Eur J Plant Pathol 133: 295–313 doi: 10.1007/s10658-012-9936-1 [ Google Scholar ]

- View on publisher site

- PDF (179.7 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

What is an article critique? An article critique requires you to critically read a piece of research and identify and evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of the article. How is a critique different from a summary?

By mastering the art of how to critique a research article, you’ll develop critical thinking skills, deepen your understanding of research methodologies, and enhance your ability to contribute meaningfully to academic discussions.

First, we’ll discuss what a research article critique is and its importance. Then, we’ll outline the key points to consider when critiquing a scientific article. Finally, we’ll provide a step-by-step guide on how to write an article critique including introduction, body and summary.

A critique asks you to evaluate an article and the author’s argument. You will need to look critically at what the author is claiming, evaluate the research methods, and look for possible problems with, or applications of, the researcher’s claims.

If you are asked to write a critique of a research article, you should focus on these issues. You will also need to consider where and when the article was published and who wrote it. This handout presents guidelines for writing a research critique and questions to consider in writing a critique. 1 Taylor, G. (2009).

article's main points adequately and compile your evaluation and review of the article. The University of Waterloo's guide, "How to Write a Critique," recommends that your evaluation contain the answers to the following questions: What are the author's credentials or areas of expertise? Do you agree with the author?

A critical review (some times called a summary and critique) is similar to a liter ature. review (see Chapter 15, Writing a Literature Review), except that it is a review of. one article. This...

Introduction. This should include: Evidence of a literature review that is relevant and recent, critically appraising other works rather than merely describing them. Background information on the study to orientate the reader to the problem. Hypothesis or aims of the study.

Finding, understanding and critiquing quality articles can be a difficult process. This article sets out some helpful indicators to assist the novice to make sense of research.

Rule 5: Keep the Review Focused, but Make It of Broad Interest. Whether your plan is to write a mini- or a full review, it is good advice to keep it focused 16, 17. Including material just for the sake of it can easily lead to reviews that are trying to do too many things at once.