- Advertise with us

- History Magazine

- History of England

The Origins & Causes of the English Civil War

We English like to think of ourselves as gentlemen and ladies; a nation that knows how to queue, eat properly and converse politely. And yet in 1642 we went to war with ourselves…

Victoria Masson

We English like to think of ourselves as gentlemen and ladies; a nation that knows how to queue, eat properly and converse politely. And yet in 1642 we went to war with ourselves. Pitting brother against brother and father against son, the English civil war is a blot on our history. Indeed, there was barely an English ‘gentleman’ who was not touched by the war.

Yet how did it start? Was it simply a power struggle between king and Parliament? Were the festering wounds left by the Tudor religious roller coaster to blame? Or was it all about the money?

Divine right – the God given right of an anointed monarch to rule unhindered – was established firmly in the reign of James I (1603-25). He asserted his political legitimacy by decreeing that a monarch is subject to no earthly authority; not the will of his people, the aristocracy or any other estate of the realm, including Parliament. Under this definition any attempt to depose, dethrone or restrict the powers of the monarch goes against the will of God. The concept of a God given right to rule was not born in this period however; writings as far back as AD 600 infer that the English in their varied Anglo-Saxon states accepted those in power had God’s blessing.

This blessing should create an infallible leader – and there is the rub. Surely if you have been given power to rule by God, you should demonstrate an ability to wield this responsibility with a degree of success? By 1642 Charles I found himself nearly bankrupt, surrounded by blatant corruption and nepotism and desperate to hold onto the thin veil that masked his religious uncertainty. He was by no means an infallible leader, a fact that was glaringly obvious to both Parliament and the people of England.

Parliament had no tangible power at this point in English history. They were a collection of aristocrats who met at the King’s pleasure to offer advice and to help him collect taxes. This alone gave them some influence, as the king needed their seal of approval to legitimately set taxes in motion. In times of financial difficulty that meant the King had to listen to Parliament. Stretched thinly through the lavish lifestyles and expensive wars of the Tudor and Stuart period, the Crown was struggling. Coupled with his desire to extend his high Anglican (read here thinly disguised Catholic) policies and practices to Scotland, Charles I needed the financial support of Parliament. When this support was withheld, Charles saw it as an infringement on his Divine Right and as such, he dismissed Parliament in March 1629. The following eleven years, during which Charles ruled England without a Parliament, are referred to as the ‘personal rule’. Ruling without Parliament was not unprecedented but without access to Parliament’s financial pulling power, Charles’s ability to acquire funds was limited.

Charles’s personal rule reads like a ‘how to annoy your countrymen for dummies’. His introduction of a permanent Ship Tax was the most offensive policy to many. Ship Tax was an established tax that was paid by counties with a sea border in times of war. It was to be used to strengthen the Navy and so these counties would be protected by the money they paid in tax; in theory, it was a fair tax against which they could not argue.

Charles’s decision to extend a year-round Ship Tax to all counties in England provided around £150,000 to £200,000 annually between 1634 and 1638. The resultant backlash and popular opposition however proved that there was growing support for a check on the power of the King.

This support did not just come from the general tax paying population but also from the Puritanical forces within Protestant England. After Mary I , all subsequent English monarchs have been overtly Protestant. This stabilization of the religious roller coaster calmed the fears of many in Tudor times who believed if a civil war was to be fought in England it would be fought along religious lines.

While outwardly a Protestant, Charles I was married to a staunch Catholic, Henrietta Maria of France. She heard Roman Catholic mass every day in her own private chapel and frequently took her children, the heirs to the English throne, to mass. Furthermore, Charles’ support for his friend Archbishop William Laud’s reforms to the English Church were seen by many as a move backwards to the popery of Catholicism. The re-introduction of stained glass windows and finery within churches was the last straw for many Puritans and Calvinists.

To prosecute those who opposed his reforms, Laud used the two most powerful courts in the land, the Court of High Commission and the Court of Star Chamber. The courts became feared for their censorship of opposing religious views and were unpopular among the propertied classes for inflicting degrading punishments on gentlemen. For example, in 1637 William Prynne, Henry Burton and John Bastwick were pilloried, whipped, mutilated by cropping and imprisoned indefinitely for publishing anti-episcopal pamphlets.

Charles’s continued support for these types of policies continued to pile on support for those that were looking to put a limit on his power.

By October 1640, Charles’ unpopular religious policies and attempts to extend his power north had resulted in a war with the Scots. This was a disaster for Charles who had neither the money nor the men to fight a war. He rode north to lead the battle himself, suffering a crushing defeat that left Newcastle upon Tyne and Durham occupied by Scottish forces.

Public demands for a Parliament were growing and Charles realised that whatever his next step was to be, it would require a financial backbone. After the conclusion of the humiliating Treaty of Ripon that let the Scots remain in Newcastle and Durham whilst being paid £850 a day for the privilege, Charles summoned Parliament. Being called upon to help King and country instilled a sense of purpose and power into this new Parliament. They now presented an alternative power in the country to the King. The two sides in the English Civil war had been established.

The slide to war becomes more pronounced from this stage onwards. That is not to say it was inevitable, or that the subsequent removal and execution of Charles I was even a notion in the heads of those who opposed him. However, the balance of power had begun to shift. Parliament wasted no time arresting and putting on trial the Kings closest advisers, including Archbishop Laud and Lord Strafford.

In May 1641 Charles conceded an unprecedented act, which forbade the dissolution of the English Parliament without Parliament’s consent. Thus emboldened, Parliament now abolished Ship Tax and the courts of The Star Chamber and The High Commission.

Over the next year Parliament began to introduce increased emboldened demands, and by June 1642 these were too much for Charles to bear. His bullish response in barging into the House of Commons and attempting to arrest five MPs lost him the last remnants of support among undecided MPs. The sides were crystallized and the battle lines were drawn. Charles I raised his standard on 22nd August 1642 in Nottingham: the Civil War had begun.

So the origins of the English Civil War are complex and intertwined. England had managed to escape the Reformation relatively unscathed, avoiding much of the heavy fighting that raged in Europe as Catholic and Protestant forces battled in The Thirty Year War. However, the scars of the Reformation were still present beneath the surface and Charles did little to avert public fears about his intentions for the religious future of England.

Money had also been an issue from the outset, especially as the royal coffers had been emptied during the reigns of Elizabeth I and James I. These issues were exacerbated by Charles’s mismanagement of the public coffers and through introducing new and ‘unfair’ taxes he simply added to the already growing anti-Crown sentiment up and down the country.

These two points demonstrate the fact that Charles believed in his Divine Right, a right to rule unchallenged. Through the study of money, religion and power at this time it is clear that one factor is woven through them all and must be noted as a major cause of the English Civil War; that is the attitude and ineptitude of Charles I himself, perhaps the antithesis of an infallible monarch.

Battles of the First English Civil War:

History in your inbox

Sign up for monthly updates

Advertisement

Next article.

Oliver Cromwell

The year 2011 marked the 350th anniversary of the execution of Oliver Cromwell, Lord Protector of England - two and half years AFTER his death..

Popular searches

- Castle Hotels

- Coastal Cottages

- Cottages with Pools

- Kings and Queens

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

English Civil Wars

By: History.com Editors

Updated: September 10, 2021 | Original: December 2, 2009

Between 1642 and 1651, armies loyal to King Charles I and Parliament faced off in three civil wars over longstanding disputes about religious freedom and how the “three kingdoms” of England, Scotland and Ireland should be governed. Notable outcomes of the wars included the execution of King Charles I in 1649, 11 years of republican rule in England and the establishment of Britain’s first standing national army.

Background: The Rise of the Stuarts and King Charles I

England’s last Tudor monarch, Elizabeth I , died in 1603, and was succeeded by her cousin, James Stuart . Already King James VI of Scotland, he became King James I of England and Ireland as well, uniting the three kingdoms under a single ruler for the first time. Though at first the Catholic minority in England welcomed James’ ascension to the throne, they later turned against his regime, even attempting to blow up the king and Parliament in the Gunpowder Plot .

James’ son, Charles I, succeeded him on the throne in 1625. His marriage to a Catholic princess, Henrietta Maria of France fueled suspicions (especially among more radical Protestants, known as Puritans ) that the king would introduce Catholic traditions back into the Church of England. Charles also believed strongly in his divine right to rule, and in 1629 he dismissed Parliament altogether; he would not recall it for the next 11 years.

War in Scotland

Beginning in the late 1630s, Charles made efforts to establish a more English-like religious practice in Scotland, generating fierce resistance among that country’s Presbyterian majority. A Scottish army defeated Charles’ forces and invaded England, forcing Charles to recall Parliament in 1640 to generate the money to pay his own troops and settle the conflict. Instead, Parliament acted quickly to restrict the king’s powers, even ordering the trial and execution of one of his chief ministers, Lord Strafford.

Amid the political upheaval in London, the Catholic majority in Ireland rebelled, massacring hundreds of Protestants there in October 1641. Tales of the violence inflamed tensions in England, as Charles and Parliament disagreed on how to respond. In January 1642, the king tried and failed to arrest five members of Parliament who opposed him. Fearing for his own safety, Charles fled London for northern England, where he called on his supporters to prepare for war.

Did you know? In May 1660, nearly 20 years after the start of the English Civil Wars, Charles II finally returned to England as king, ushering in a period known as the Restoration.

First English Civil War (1642-46)

When civil war broke out in earnest in August 1642, Royalist forces (known as Cavaliers) controlled northern and western England, while Parliamentarians (or Roundheads) dominated in the southern and eastern regions of the country. The king’s forces appeared to be gaining the upper hand by early 1643, especially after concluding an alliance with Irish Catholics to end the Irish Rebellion. But a key alliance between the Parliamentarians and Scotland that year led to a large Scottish army joining the fray on Parliament’s side in January 1644.

On July 2, 1644, Royalist and Parliamentarian forces met at Marston Moor, west of York, in the largest battle of the First English Civil War. A Parliamentarian force of 28,000 routed the smaller Royalist army of 18,000 , ending the king’s control of northern England. In 1645, Parliament created a permanent, professional, trained army of 22,000 men. This New Model Army, commanded by Sir Thomas Fairfax and Oliver Cromwell , scored a decisive victory in June 1645 in the Battle of Naseby, effectively dooming the Royalist cause.

Second English Civil War (1648-49) and execution of King Charles I

Even in defeat, Charles refused to give in, but sought to capitalize on the religious and political divisions among his enemies. While on the Isle of Wight in 1647-48, the king managed to conclude a peace treaty with the Scots and marshal Royalist sentiment and discontent with Parliament into a series of armed uprisings across England in the spring and summer of 1648.

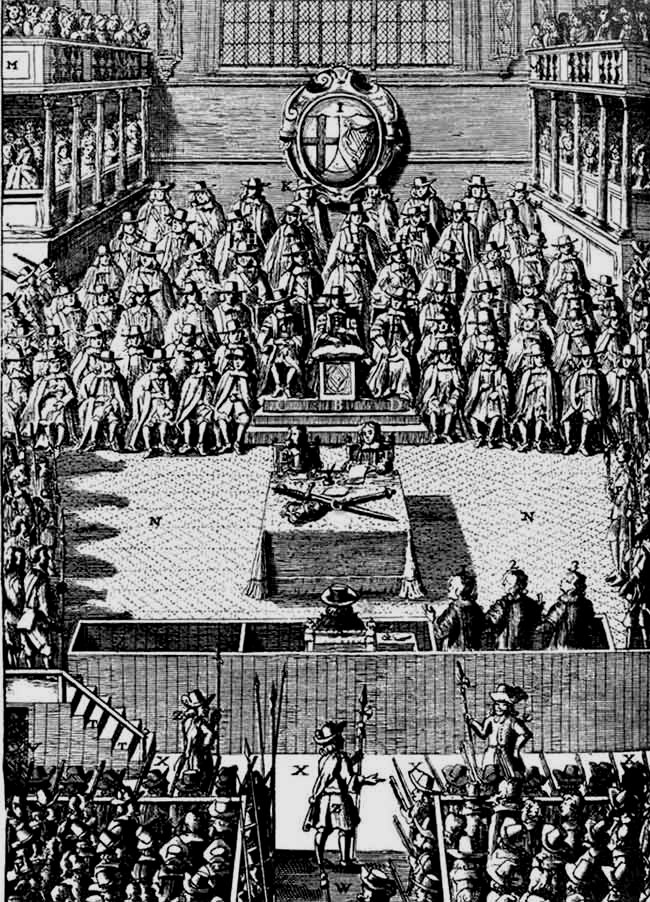

After Fairfax, Cromwell and the New Model Army easily crushed the Royalist uprisings, hard-line opponents of the king took charge of a smaller Parliament. Concluding that peace could not be reached while Charles was still alive, they set up a high court and put the king on trial for treason. Charles was found guilty and executed by beheading on January 30, 1649 at Whitehall.

Third English Civil War (1649-51)

With Charles dead, a republican regime was established in England, backed by the military might of the New Model Army. Beginning late in 1649, Cromwell led his army in a successful reconquest of Ireland, including the notorious massacre of thousands of Irish and Royalist troops and civilians at Drogheda. Meanwhile, Scotland came to an agreement with the executed king’s eldest son, also named Charles, who was crowned King Charles II of Scotland in early 1651.

Even before he was officially crowned, Charles II had formed an army of English and Scottish Royalists, prompting Cromwell to invade Scotland in 1650. After losing the Battle of Dunbar to Cromwell’s forces in September 1650, Charles led an invasion of England the following year, only to suffer another defeat against a huge Parliamentarian army at Worcester. The young king narrowly escaped capture, but the decisive victory ended the Third English Civil War, along with the larger War of the Three Kingdoms (England, Scotland and Ireland).

Impact of the Civil Wars

An estimated 200,000 English soldiers and civilians were killed during the three civil wars, by fighting and the disease spread by armies; the loss was proportionate, population-wise, to that of World War I.

In 1653, Oliver Cromwell was installed as Lord Protector of the Commonwealth of England, Scotland and Ireland, and tried (largely unsuccessfully) to consolidate broad support behind the new republican regime amid the continued growth of radical religious sects and widespread uneasiness about the new standing army.

After Cromwell’s death in 1658, he was succeeded as protector by his son Richard, who abdicated just eight months later. With the continued disintegration of the republic, the larger Parliament was reassembled, and began negotiations with Charles II to resume the throne. The triumphant king arrived in London in May 1660, beginning the English Restoration .

British Civil Wars. National Army Museum .

Mark Stoyle. Overview: Civil War and Revolution, 1603-1714. BBC .

The English Civil Wars: Origins, events and legacy. English Heritage .

Simon Jenkins. A Short History of England: The Glorious Story of a Rowdy Nation . (PublicAffairs, 2011)

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

The English Civil Wars are traditionally considered to have begun in England in August 1642, when Charles I raised an army against the wishes of Parliament, ostensibly to deal with a rebellion in Ireland.

The English Civil Wars (1642-1651) were caused by a monumental clash of ideas between King Charles I of England (r. 1625-1649) and his parliament. Arguments over the powers of the monarchy, finances...

The English Civil War permanently and directly shaped the balance of power between the monarch and the parliament of England. The underlying problems facing Charles I during his reign began in the 16th century.

The Origins & Causes of the English Civil War. We English like to think of ourselves as gentlemen and ladies; a nation that knows how to queue, eat properly and converse politely. And yet in 1642 we went to war with ourselves… Victoria Masson. 12 min read.

The English Civil Wars (1642‑1651) stemmed from conflict between King Charles I and Parliament over an Irish insurrection. The wars ended with the Parliamentarian victory at the Battle of...

The English Civil War broke out in 1642, less than 40 years after the death of Queen Elizabeth I. Elizabeth had been succeeded by her first cousin twice-removed, King James VI of Scotland, as James I of England, creating the first personal union of the Scottish and English kingdoms.

The English Civil war took place in 1642 until around 1650 and included warfare in not just England but also Scotland and Ireland. The two opposing sides were the English parliamentary party and English monarch, King Charles I.

Incorporating Scotland and Ire-land as well as England, it highlights how scholarship by later-Stuart historians and by those working on “history from below” exposed the limitations of Revi-sionism, and it points to the need to seek long-term explanations for the origins of the English civil war.

*,"-: early Stuart political historiography; ...

The English Civil War (1642-1651) was caused by conflicts between King Charles I and Parliament over political power and religious freedoms. Key events included the...

What was the main cause of the English Civil War? The English Civil Wars were caused by an ongoing dispute between King Charles I of England and the English Parliament over political power, finances, and religious reforms.