- Open access

- Published: 25 August 2018

Unsafe abortion and associated factors among reproductive aged women in Sub-Saharan Africa: a protocol for a systematic review and meta-analysis

- Merhawi Gebremedhin 1 ,

- Agumasie Semahegn 1 , 3 ,

- Tofik Usmael 2 &

- Gezahegn Tesfaye 1

Systematic Reviews volume 7 , Article number: 130 ( 2018 ) Cite this article

42k Accesses

29 Citations

95 Altmetric

Metrics details

Unsafe abortion is a neglected public health problem contributing for 13% of maternal death worldwide. In Africa, 99% of abortions are unsafe resulting in one maternal death per 150 cases. The prevalence of unsafe abortion is associated with restricted abortion law, poor quality of health service, and low community awareness. Hence, the aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis is to identify and summarize the available evidence to generate an abridged evidence on the prevalence of unsafe abortion and its associated factors in Sub-Saharan Africa.

The development of the systematic review methodology has followed the procedural guideline depicted in the preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocol statement. Observational studies that have been conducted from January 1, 1994, up to December 31, 2017, in Sub-Saharan African countries will be included in the systematic review and meta-analysis. MEDLINE (via PubMed), EMBASE, CINAHL, and PopLine will be searched to retrieve available studies. Relevant studies will be retrieved using the search strings applied to different sources. The Joanna Briggs Institute quality assessment tool will be used to critically appraise the methodological robustness and validity of the finding to avoid erroneous data due to confounded or biased statistics. Data extraction template will be prepared to record abstracted information from selected studies. The selection of relevant studies, data extraction, and quality assessment of studies will be carried out by two authors. Meta-analysis using Mantel–Haenszel random effects model will be carried out. The presence of heterogeneity between studies will be checked using the I 2 value.

Unsafe abortion is not yet reduced significantly in Sub-Saharan Africa, and maternal death rate due to unsafe abortion remains high. Currently, there is a gap in availability of abridged evidence on unsafe abortion and this negatively influenced the current service delivery. This finding will help stakeholders to design appropriate strategy. The finding of this systematic review and meta-analysis will be helpful to inform policy-makers, programmers, planners, clinician’s decision making, researchers, and women clients at large.

Systematic review registration

PROSPERO 2017: CRD42017081437 .

Peer Review reports

Unsafe abortion is entirely preventable. However, it remains pandemic and serious public health issue worldwide [ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 ]. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines unsafe abortion as a procedure of pregnancy termination either by persons lacking the necessary skills or in an environment that does not conform to minimal medical standards or both [ 5 ]. Unsafe abortion is a neglected problem of health care in developing countries [ 4 ]. Despite technological advancements in health care, unsafe abortion remained essentially unchanged worldwide [ 6 ]. Unsafe abortion is identified as one of the major cause of maternal morbidity and mortality [ 7 ]. In Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), abortion is more common and it tends to be clandestine and unsafe that has a substantially contribution to maternal mortality [ 8 ].

Worldwide, 210 million women become pregnant each year. Of these, 80 million pregnancies are unplanned. Out of these, 46 million pregnancies terminated each year, and 19 million ends with unsafe abortion [ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 ]. More than 97% of unsafe abortions take place in developing countries [ 2 , 4 , 9 , 10 ]. Globally, unsafe abortion increased from 44% in 1995 to 49% in 2008 [ 2 , 10 ]. In 2000, the WHO estimates that one in ten pregnancies end up with unsafe abortion, giving one unsafe abortion to seven live births ratio. Likewise, 68,000 women die due to unsafe abortion each year, and the risk of maternal death is high in developing countries (1 in 270 unsafe abortion) [ 4 ].

The maternal death associated with unsafe abortion was 37 deaths per 100,000 live births in SSA, 23 per 100,000 in Latin America and the Caribbean, and 12 per 100,000 in South Asia [ 1 ]. The WHO (2008) estimates that unsafe abortion contributes for 13% of maternal death, worldwide. However, in Africa, the contribution of unsafe abortion is too high which is 2.4 million unsafe abortions occurred in eastern Africa in 2008. Globally, 40% of reproductive aged women live in countries with highly restrictive abortion law [ 11 ]. In Africa, over 4 million unsafe abortions are carried out yearly; mostly on poor, rural, and young women lacking information on availability of safe abortion care. About 99% of all abortions carried out in Africa are unsafe, and the risk of maternal death from an unsafe abortion is one in every 150 procedures which is the highest in the world [ 12 , 13 ].

The prevalence of unsafe abortion is attributable to poverty, social inequity, and denial of women’s human rights [ 1 ]. Countries with restricted abortion or where abortions are clandestine and unsafe, its consequences to women’s health are harmful, particularly for young, poor, and low-education women [ 3 , 14 ]. Unsafe abortion is practiced using different methods such as use of oral and injectable items, vaginal preparations, intrauterine foreign bodies, and trauma to the abdomen [ 13 ]. Significant proportion of women (20–50%) with unsafe abortion develop complications that lead to hospital admission. These complications include hemorrhage, sepsis, peritonitis, and trauma to the cervix, vagina, uterus, and abdominal organs [ 2 ]. The Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) aim to reduce global maternal mortality ratio from 216 to 70 per 100, 000 live births by 2030. Therefore, in order to contribute to this goal, developing countries need to legalize abortion and improve health care system to reduce abortion-related maternal deaths [ 2 , 15 ]. Hence, the main purpose of this systematic review and meta-analysis is to identify and summarize the available evidence to determine prevalence of unsafe abortion among women in the reproductive age and associated factors in SSA.

Development review protocol and registration

The development of the review methodology has followed the procedural guideline that was endorsed by the preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocol (PRISMA-P) statement [ 16 ], and all of the items in the checklist were completed (see Additional file 1 ). The review protocol has been registered in international prospective register of systematic reviews (PROSPERO) with trial registration number (CRD42017081437).

Data source and searching strategies

The search of studies will be carried out by (MG and GT). Published and unpublished studies written in English will be retrieved and included into the review process. Databases such as MEDLINE (via PubMed), EMBASE, CINAHL, and POPLINE will be searched for studies that had been conducted since January 1, 1994. Relevant sources such as Google search engine, Google scholar, and WHO websites will be searched. In addition, experts on the field will be consulted to retrieve unpublished studies. The year 1994 was chosen because the international community recognized the pressing need to address unsafe abortion at the International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD) in the year 1994 [ 17 ] and many African countries endorsed semi-restricted abortion law since 1994 [ 18 ]. The search strings will emerge from the following keywords (unsafe abortion, induced abortion, abortion, Sub-Saharan Africa, or African South of Sahara). Depending on the specific requirement of the database, the search string will be modified, and relevant studies using search strings will be identified. The combinations of free keywords and MeSH (medical sub-headings) will be extensively used in the search process. The reference lists of relevant studies will also be reviewed for sources that may have been missed in the database search. The search strategy developed for selected database is attached (see Additional file 2 ).

Eligibility criteria

All observational studies (cross-sectional, case-control, and cohort) and survey reports will be included in the systematic review. However, case reports, case series, commentaries, and editorials will be excluded from the review. All studies with primary objective to determine the prevalence of unsafe abortion and/or its associated factors among reproductive aged women in Sub-Saharan Africa will be considered [ 8 ].

We will consider studies that defined unsafe abortion based on WHO definition [ 19 ]; WHO defines unsafe abortion as a procedure of pregnancy termination either by persons lacking the necessary skills or in an environment that does not conform to minimal medical standards or both. We will also include community or facility-based studies that used either primary or secondary data. We will include studies that had mainly reported prevalence of unsafe abortion and its associated factors. However, as far as our primary aim is to determine the prevalence of unsafe abortion, studies that reported only prevalence of unsafe abortion but not associated factors will be included. In addition, studies that at least had test statistics that measured association between predictor variables with unsafe abortion will be considered to identify the associated factors. The studies should have a crosstab showing difference in prevalence of unsafe abortion in the categories of the exposure variables. We will exclude studies that only investigated unsafe abortion with qualitative approach. If we come across studies that have both quantitative and qualitative study finding, we will only consider the quantitative findings.

Selection of studies

We will export all retrieved studies into the Endnote citation management software [ 20 ]. Initially, duplicated studies will be removed from the citation manger. The two authors (MG and AS) will independently screen the studies based on information contained in the titles and abstract based on the inclusion criteria. Studies that clearly mentioned unsafe abortion among reproductive aged women will be selected for the next step of evaluation. Consequently, studies that have been eligible based on their title and abstract will be further screened by GT and TU. Based on title and abstract assessment, the studies will be classified as included, excluded, and undecided studies. For studies that will be categorized as included and undecided, we will further examine and evaluate full texts of the studies for eligibility. The full-text screening will be carried out by GT and AS. Studies that will not be eligible based on the full-text assessment will be excluded and reasons will be described for their exclusion. Studies that will pass through this selection process will be included in qualitative and quantitative synthesis. During screening of the studies, any disagreement among reviewers will be resolved by discussion and reach common understanding. The study selection process flow diagram is adapted from PRISMA guideline [ 16 ] (see Additional file 3 ).

Quality assessment

Studies will be critically evaluated for their validity of the findings. To determine the methodological robustness and validity of the findings of the studies, we will use the JBI (Joanna Briggs Institute) tool for assessing the quality of evidence. Particular attention will be given to clear statement of the objective of the study, sampling techniques, precision of measurement of outcomes of interest and exposure variables, as well as documentation of sources of bias or confounding. The two review authors (GT and AS) will check the scientific quality of the studies independently using quality assessment tool mentioned above. In case of uncertainties, it will be resolved by joint discussion between them.

Data extraction

Data extraction template will be constructed on Microsoft Excel (2013). The two authors (MG and TU) will extract data systematically and stored using data extraction form. Piloting of the data extraction form will be carried out before the beginning of the actual data extraction. Study description tables will be used to record the type of study design, aim, sample size, primary outcomes of interest (prevalence of unsafe abortion), and secondary outcome (associated factors). Numerical data (frequency) will also be extracted and recorded in Microsoft Excel sheet. The systematic review and meta-analysis working group will contact authors of the studies to request for details through email in case of missing data, incomplete report, or any uncertainties.

Data synthesis and statistical analysis

The data will first be presented using narrative synthesis of the included studies. A summary table will be prepared to describe characteristics (author-date, country, design, aim, sampling method, sample size, response rate, and key findings) of the included studies. The presence of statistical heterogeneity will be checked by using the Cochran Q test. The level of heterogeneity among the studies will be quantified using the I 2 statistics where substantial heterogeneity will be assumed if the I 2 value is ≥ 60%. We will also check the presence of publication bias using funnel plot if more than ten studies are included. We will also do Egger’s and Beggar’s test to check publication bias [ 21 ]. To pool prevalence of unsafe abortion, we will conduct meta-analysis using Comprehensive Meta-analysis software [ 22 ]. We will use the random effects model and the raw numerical data (number of unsafe abortions ( n ) and total sample size ( N )) from each study. We hypothesize that the legal and illegal status of abortion influences the magnitude of unsafe abortion. Therefore, we will conduct sub-group analysis of the prevalence of unsafe abortion based on countries abortion legal status. Moreover, we will use adjusted, and if none available unadjusted, odds ratios to assess the association between risk factors and unsafe abortion.

The aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis is to synthesis research findings on the prevalence of unsafe abortion and its associated factor in SSA. Even though evidence [ 23 ] indicates that unsafe abortion is not showing reduction in SSA, there is no systematically reviewed evidence that show the overall prevalence of unsafe abortion and influencing factors in the region. Moreover, currently, there is a gap in the availability of complete data on unsafe abortion and this can negatively influence the prevailing service delivery [ 24 ]. Establishing reliable evidence on the magnitude of unsafe abortion are generally challenging especially in countries where access to abortion is legally restricted. Whether legal or illegal, induced abortion is usually stigmatized and frequently censured by political, religious, or other cultural issues. Hence, under-reporting is routine even in countries where abortion is legally available [ 25 ].

The magnitude of unsafe abortion can be measured using different approaches namely absolute numbers, incidence ratio, incidence rate, mortality ratio, and case fatality rate. However, absolute number of unsafe abortions cannot be used to compare the magnitude in different regions or sub-regions because of difference in population size. In our analysis, ratios and rates will be used to allow inter or intra comparisons of nation(s) [ 4 ]. Worldwide report indicates that the rate of unsafe abortion is not decreased at the same pace with that of safe abortion. Unsafe abortions changed very little: from 19.9 million in 1995 to 19.7 million in 2003 [ 26 ]. But there is no specific data that indicates the prevalence of unsafe abortion to support the current initiative to reduce the rate of unsafe abortion in the region.

Evidence indicates that maternal mortality ratio secondary to unsafe abortion is 950 times higher in SSA (520) than in the USA (0.6) per 100,000 live births, respectively. The burdens of unsafe abortion and its associated maternal mortality are disproportionately higher for women in Africa than in any other developing region [ 27 ]. Its share of global unsafe abortions was 29%, and more seriously, 62% of all deaths related to unsafe abortion occurred in Africa in 2008 [ 28 ]. In places where laws and policies allow abortion under broad indications, the incidence of and mortality from unsafe abortion are reduced to a minimum [ 28 ].

Meanwhile, unsafe abortion affects the health of millions of women predominantly the poor, illiterate, and those living in rural areas, and hence, knowing the prevailing situation of unsafe abortion could help develop appropriate programs that potentially circumvent its occurrence. Experts proposed that expanding effective modern contraceptive methods, making abortion legal with accessible safe abortion services, and improving the quality of post abortion care would reduce the magnitude of unsafe abortion, its associated maternal mortality and morbidity, and cost of post abortion services [ 26 , 29 ]. Systematic review conducted in SSA showed that care givers in general were uncertain about the legal status of abortion in their countries, with majority of them having negative feeling towards induced abortion and only some of the health care providers perceived the legalization of abortion as a positive step [ 1 ].

Subsequently, it remains important to assess the magnitude of unsafe abortion and its associated factors in SSA so as to inform the development of appropriate programs and policy that would have an impact in reducing maternal morbidity and mortality in the region. The finding from this systematic review will be important for national governments and nongovernmental organizations in the health sector of the individual countries of the region to give emphasis on the main factors that drive unsafe abortion. Moreover, this finding will also help governments and other health development partners to expand and improve family planning services, to further advocate for legalization of abortion and increase accessibility and availability of abortion services in order to improve women’s health and well-being [ 4 ]. Therefore, the finding of this systematic review and meta-analysis will be used to inform policy-makers, health programmers, clinicians’ decision making, researchers, human right activist, and women clients at large.

Abbreviations

International Conference on Population and Development

Joanna Briggs Institute

Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis

Sustainable Development Goals

- Sub-Saharan Africa

World Health Organization

Rehnström Loi U, Gemzell-Danielsson K, Faxelid E, Klingberg-Allvin M. Health care providers’ perceptions of and attitudes towards induced abortions in sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia: a systematic literature review of qualitative and quantitative data. BMC Public Health. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-1502-2 .

Grimes DA, Benson J, Singh S, Romero M, Ganatra B, Okonofua FE, Shah IH. Unsafe abortion: the preventable pandemic. Sex Reprod Health. 2006. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69481-6 .

CLB F. Unsafe abortion: a serious public health issue in a poverty stricken population. Reprod Clim. 2013;2(8):2–9.

WHO. Unsafe abortion: global and regional estimates of the incidence of unsafe abortionand associated mortality. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004. ISBN 92 4 159180 3

Google Scholar

WHO. HRP annual report; WHO Department of Reproductive Health and Research. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016. WHO/RHR/HRP/17.06

WHO. Interagency list of priority medical devices for essential interventions for reproductive, maternal newborn and child health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016.

Benson J, Nicholson LA, Gaffucin L, Kinoti SN. Complications of unsafe abortion in sub-Saharan Africa: a review. Health Policy Plan. 1996;11(2):117–31.

Kulczycki A.The imperative to expand provision, access and use of misoprostol for post-abortion care in sub-Saharan Africa. 2016.

Facts on induced abortion worldwide. http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/unsafe_abortion/abortion_facts/en/ . Accessed 23 Dec 2017.

Shah IH, Åhman E. Unsafe abortion differentials in 2008 by age and developing country region: high burden among young women; 2012. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0968-8080(12)39598-0 .

Book Google Scholar

Rasch V, Sørensen PH, Wang AR, Tibazarwa F, Jäger AK. Unsafe abortion in rural Tanzania – the use of traditional medicine from a patient and a provider perspective. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14:419.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Abortion law reform in Sub-Saharan Africa: no turning back: an international journal on sexual and reproductive health and rights, 2005. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0968-8080(04)24026-5 .

Guttmacher Institute. Abortion and unintended pregnancy in Kenya. 2012: No. 2.

Grimes DA, Benson J, Singh S, Romero M, Ganatra B, Okonofua FE, Shah IH. Unsafe abortion: the preventable pandemic. Lancet. 2006;368:1908–19.

HEARD. Unsafe abortion in South Africa: country factsheet. Durban: Health Economics and HIV/AIDS Research Division/ University of KwaZuluNatal; 2006.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman D. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PloS Med. 2009;6(7)

McIntosh CA, Finkle JL. The Cairo conference on population and development: a new paradigm? Popul Dev Rev. 1995:223–60.

Brookman-Amissah E, Moyo JB. Abortion law reform in sub-Saharan Africa: no turning back. Reprod Health Matters. 2004;12(24):227–34.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

WHO. Unsafe abortion: global and regional estimates of the incidence of unsafe and associated mortality. Geneva: World Health Orgnzaiation; 2008.

Reuters T. Cite While You Write TM Patented technology U.S patent number 8,092,24119888-2015. inventorEndNote X 7.3.1 (BId 8614). 2015.

Higgins JPT, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21(11):1539–58. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.1186 .

Borenstein M, Hedges L, Higgins J, Rothstein H. Comprehensive meta analysis (CMA) version 2.0. 2004.

WHO. Safe abortion: technical and policy Guidance for health system. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2012. ISBN 978 92 4 154843 4

WHO. Countdown to 2015 decade report (2000–2010): taking stock of maternal, newborn and child survival. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. ISBN 978 92 4 159957 3

Unsafe abortion: the preventable pandemic. pulisher, Lancet online. 2006. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69481-6 .

S Singh, et, al. Abortion worldewide: a decade of uneven progress. [Online] 2003.

Shah I, Ahman E. Unsafe abortion: global and regional incidence, trends, consequences and challenges. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2009:1149–58.

WHO. Unsafe abortion: global and regional estimates of the incidence of unsafe abortion and associated mortality in 2008. Geneva: WHO; 2011.

GUTT AMACHER INSTITUTE. Facts on induced abortion worldwide. 2012.

Download references

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Haramaya University, College Health and Medical Sciences, for the office arrangement and free internet access.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

College of Health and Medical Sciences, Haramaya University, PO Box 235, Harar, Ethiopia

Merhawi Gebremedhin, Agumasie Semahegn & Gezahegn Tesfaye

IPAS Ethiopia, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

Tofik Usmael

School of Public Health, College of Health Science, University of Ghana, Legon, Accra, Ghana

Agumasie Semahegn

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

MG, AS, TU, and GT conceived and designed the systematic review and meta-analysis. MG, AS, and GT drafted the protocol manuscript, and MG is the guarantor of the review. MG and GT developed the search strings. MG, AS, GT, and TU extensively reviewed and incorporated intellectual inputs in the protocol manuscript development. All authors read and approved the final version of the protocol manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Merhawi Gebremedhin .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:.

PRISMA-P checklist. (DOC 84 kb)

Additional file 2:

Sample search strategy using search strings. (PDF 19 kb)

Additional file 3:

Diagramatic presentation of the studies selection process for systematic review. (DOCX 36 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Gebremedhin, M., Semahegn, A., Usmael, T. et al. Unsafe abortion and associated factors among reproductive aged women in Sub-Saharan Africa: a protocol for a systematic review and meta-analysis. Syst Rev 7 , 130 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-018-0775-9

Download citation

Received : 23 January 2018

Accepted : 13 July 2018

Published : 25 August 2018

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-018-0775-9

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Systematic review and meta-analysis

- Unsafe abortion

Systematic Reviews

ISSN: 2046-4053

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Ethics and Morality

Ethics and abortion, two opposing arguments on the morality of abortion..

Posted June 7, 2019 | Reviewed by Jessica Schrader

Abortion is, once again, center stage in our political debates. According to the Guttmacher Institute, over 350 pieces of legislation restricting abortion have been introduced. Ten states have signed bans of some sort, but these are all being challenged. None of these, including "heartbeat" laws, are currently in effect. 1

Much has been written about abortion from a philosophical perspective. Here, I'd like to summarize what I believe to be the best argument on each side of the abortion debate. To be clear, I'm not advocating either position here; I'm simply trying to bring some clarity to the issues. The focus of these arguments is on the morality of abortion, not its constitutional or legal status. This is important. One might believe, as many do, that at least some abortions are immoral but that the law should not restrict choice in this realm of life. Others, of course, argue that abortion is immoral and should be illegal in most or all cases.

"Personhood"

Personhood refers to the moral status of an entity. If an entity is a person , in this particular sense, it has full moral status . A person, then, has rights , and we have obligations to that person. This includes the right to life. Both of the arguments I summarize here focus on the question of whether or not the fetus is a person, or whether or not it is the type of entity that has the right to life. This is an important aspect to focus on, because what a thing is determines how we should treat it, morally speaking. For example, if I break a leg off of a table, I haven't done anything wrong. But if I break a puppy's leg, I surely have done something wrong. I have obligations to the puppy, given what kind of creature it is, that I don't have to a table, or any other inanimate object. The issue, then, is what kind of thing a fetus is, and what that entails for how we ought to treat it.

A Pro-Choice Argument

I believe that the best type of pro-choice argument focuses on the personhood of the fetus. Mary Ann Warren has argued that fetuses are not persons; they do not have the right to life. 2 Therefore, abortion is morally permissible throughout the entire pregnancy . To see why, Warren argues that persons have the following traits:

- Consciousness: awareness of oneself, the external world, the ability to feel pain.

- Reasoning: a developed ability to solve fairly complex problems.

- Ability to communicate: on a variety of topics, with some depth.

- Self-motivated activity: ability to choose what to do (or not to do) in a way that is not determined by genetics or the environment .

- Self-concept : see themselves as _____; e.g. Kenyan, female, athlete , Muslim, Christian, atheist, etc.

The key point for Warren is that fetuses do not have any of these traits. Therefore, they are not persons. They do not have a right to life, and abortion is morally permissible. You and I do have these traits, therefore we are persons. We do have rights, including the right to life.

One problem with this argument is that we now know that fetuses are conscious at roughly the midpoint of a pregnancy, given the development timeline of fetal brain activity. Given this, some have modified Warren's argument so that it only applies to the first half of a pregnancy. This still covers the vast majority of abortions that occur in the United States, however.

A Pro-Life Argument

The following pro-life argument shares the same approach, focusing on the personhood of the fetus. However, this argument contends that fetuses are persons because in an important sense they possess all of the traits Warren lists. 3

At first glance, this sounds ridiculous. At 12 weeks, for example, fetuses are not able to engage in reasoning, they don't have a self-concept, nor are they conscious. In fact, they don't possess any of these traits.

Or do they?

In one sense, they do. To see how, consider an important distinction, the distinction between latent capacities vs. actualized capacities. Right now, I have the actualized capacity to communicate in English about the ethics of abortion. I'm demonstrating that capacity right now. I do not, however, have the actualized capacity to communicate in Spanish on this issue. I do, however, have the latent capacity to do so. If I studied Spanish, practiced it with others, or even lived in a Spanish-speaking nation for a while, I would likely be able to do so. The latent capacity I have now to communicate in Spanish would become actualized.

Here is the key point for this argument: Given the type of entities that human fetuses are, they have all of the traits of persons laid out by Mary Anne Warren. They do not possess these traits in their actualized form. But they have them in their latent form, because of their human nature. Proponents of this argument claim that possessing the traits of personhood, in their latent form, is sufficient for being a person, for having full moral status, including the right to life. They say that fetuses are not potential persons, but persons with potential. In contrast to this, Warren and others maintain that the capacities must be actualized before one is person.

The Abortion Debate

There is much confusion in the abortion debate. The existence of a heartbeat is not enough, on its own, to confer a right to life. On this, I believe many pro-lifers are mistaken. But on the pro-choice side, is it ethical to abort fetuses as a way to select the gender of one's child, for instance?

We should not focus solely on the fetus, of course, but also on the interests of the mother, father, and society as a whole. Many believe that in order to achieve this goal, we need to provide much greater support to women who may want to give birth and raise their children, but choose not to for financial, psychological, health, or relationship reasons; that adoption should be much less expensive, so that it is a live option for more qualified parents; and that quality health care should be accessible to all.

I fear , however, that one thing that gets lost in all of the dialogue, debate, and rhetoric surrounding the abortion issue is the nature of the human fetus. This is certainly not the only issue. But it is crucial to determining the morality of abortion, one way or the other. People on both sides of the debate would do well to build their views with this in mind.

https://abcnews.go.com/US/state-abortion-bans-2019-signed-effect/story?id=63172532

Mary Ann Warren, "On the Moral and Legal Status of Abortion," originally in Monist 57:1 (1973), pp. 43-61. Widely anthologized.

This is a synthesis of several pro-life arguments. For more, see the work of Robert George and Francis Beckwith on these issues.

Michael W. Austin, Ph.D. , is a professor of philosophy at Eastern Kentucky University.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Teletherapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Understanding what emotional intelligence looks like and the steps needed to improve it could light a path to a more emotionally adept world.

- Coronavirus Disease 2019

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

Find anything you save across the site in your account

How the Right to Legal Abortion Changed the Arc of All Women’s Lives

By Katha Pollitt

I’ve never had an abortion. In this, I am like most American women. A frequently quoted statistic from a recent study by the Guttmacher Institute, which reports that one in four women will have an abortion before the age of forty-five, may strike you as high, but it means that a large majority of women never need to end a pregnancy. (Indeed, the abortion rate has been declining for decades, although it’s disputed how much of that decrease is due to better birth control, and wider use of it, and how much to restrictions that have made abortions much harder to get.) Now that the Supreme Court seems likely to overturn Roe v. Wade sometime in the next few years—Alabama has passed a near-total ban on abortion, and Ohio, Georgia, Kentucky, Mississippi, and Missouri have passed “heartbeat” bills that, in effect, ban abortion later than six weeks of pregnancy, and any of these laws, or similar ones, could prove the catalyst—I wonder if women who have never needed to undergo the procedure, and perhaps believe that they never will, realize the many ways that the legal right to abortion has undergirded their lives.

Legal abortion means that the law recognizes a woman as a person. It says that she belongs to herself. Most obviously, it means that a woman has a safe recourse if she becomes pregnant as a result of being raped. (Believe it or not, in some states, the law allows a rapist to sue for custody or visitation rights.) It means that doctors no longer need to deny treatment to pregnant women with certain serious conditions—cancer, heart disease, kidney disease—until after they’ve given birth, by which time their health may have deteriorated irretrievably. And it means that non-Catholic hospitals can treat a woman promptly if she is having a miscarriage. (If she goes to a Catholic hospital, she may have to wait until the embryo or fetus dies. In one hospital, in Ireland, such a delay led to the death of a woman named Savita Halappanavar, who contracted septicemia. Her case spurred a movement to repeal that country’s constitutional amendment banning abortion.)

The legalization of abortion, though, has had broader and more subtle effects than limiting damage in these grave but relatively uncommon scenarios. The revolutionary advances made in the social status of American women during the nineteen-seventies are generally attributed to the availability of oral contraception, which came on the market in 1960. But, according to a 2017 study by the economist Caitlin Knowles Myers, “The Power of Abortion Policy: Re-Examining the Effects of Young Women’s Access to Reproductive Control,” published in the Journal of Political Economy , the effects of the Pill were offset by the fact that more teens and women were having sex, and so birth-control failure affected more people. Complicating the conventional wisdom that oral contraception made sex risk-free for all, the Pill was also not easy for many women to get. Restrictive laws in some states barred it for unmarried women and for women under the age of twenty-one. The Roe decision, in 1973, afforded thousands upon thousands of teen-agers a chance to avoid early marriage and motherhood. Myers writes, “Policies governing access to the pill had little if any effect on the average probabilities of marrying and giving birth at a young age. In contrast, policy environments in which abortion was legal and readily accessible by young women are estimated to have caused a 34 percent reduction in first births, a 19 percent reduction in first marriages, and a 63 percent reduction in ‘shotgun marriages’ prior to age 19.”

Access to legal abortion, whether as a backup to birth control or not, meant that women, like men, could have a sexual life without risking their future. A woman could plan her life without having to consider that it could be derailed by a single sperm. She could dream bigger dreams. Under the old rules, inculcated from girlhood, if a woman got pregnant at a young age, she married her boyfriend; and, expecting early marriage and kids, she wouldn’t have invested too heavily in her education in any case, and she would have chosen work that she could drop in and out of as family demands required.

In 1970, the average age of first-time American mothers was younger than twenty-two. Today, more women postpone marriage until they are ready for it. (Early marriages are notoriously unstable, so, if you’re glad that the divorce rate is down, you can, in part, thank Roe.) Women can also postpone childbearing until they are prepared for it, which takes some serious doing in a country that lacks paid parental leave and affordable childcare, and where discrimination against pregnant women and mothers is still widespread. For all the hand-wringing about lower birth rates, most women— eighty-six per cent of them —still become mothers. They just do it later, and have fewer children.

Most women don’t enter fields that require years of graduate-school education, but all women have benefitted from having larger numbers of women in those fields. It was female lawyers, for example, who brought cases that opened up good blue-collar jobs to women. Without more women obtaining law degrees, would men still be shaping all our legislation? Without the large numbers of women who have entered the medical professions, would psychiatrists still be telling women that they suffered from penis envy and were masochistic by nature? Would women still routinely undergo unnecessary hysterectomies? Without increased numbers of women in academia, and without the new field of women’s studies, would children still be taught, as I was, that, a hundred years ago this month, Woodrow Wilson “gave” women the vote? There has been a revolution in every field, and the women in those fields have led it.

It is frequently pointed out that the states passing abortion restrictions and bans are states where women’s status remains particularly low. Take Alabama. According to one study , by almost every index—pay, workforce participation, percentage of single mothers living in poverty, mortality due to conditions such as heart disease and stroke—the state scores among the worst for women. Children don’t fare much better: according to U.S. News rankings , Alabama is the worst state for education. It also has one of the nation’s highest rates of infant mortality (only half the counties have even one ob-gyn), and it has refused to expand Medicaid, either through the Affordable Care Act or on its own. Only four women sit in Alabama’s thirty-five-member State Senate, and none of them voted for the ban. Maybe that’s why an amendment to the bill proposed by State Senator Linda Coleman-Madison was voted down. It would have provided prenatal care and medical care for a woman and child in cases where the new law prevents the woman from obtaining an abortion. Interestingly, the law allows in-vitro fertilization, a procedure that often results in the discarding of fertilized eggs. As Clyde Chambliss, the bill’s chief sponsor in the state senate, put it, “The egg in the lab doesn’t apply. It’s not in a woman. She’s not pregnant.” In other words, life only begins at conception if there’s a woman’s body to control.

Indifference to women and children isn’t an oversight. This is why calls for better sex education and wider access to birth control are non-starters, even though they have helped lower the rate of unwanted pregnancies, which is the cause of abortion. The point isn’t to prevent unwanted pregnancy. (States with strong anti-abortion laws have some of the highest rates of teen pregnancy in the country; Alabama is among them.) The point is to roll back modernity for women.

So, if women who have never had an abortion, and don’t expect to, think that the new restrictions and bans won’t affect them, they are wrong. The new laws will fall most heavily on poor women, disproportionately on women of color, who have the highest abortion rates and will be hard-pressed to travel to distant clinics.

But without legal, accessible abortion, the assumptions that have shaped all women’s lives in the past few decades—including that they, not a torn condom or a missed pill or a rapist, will decide what happens to their bodies and their futures—will change. Women and their daughters will have a harder time, and there will be plenty of people who will say that they were foolish to think that it could be otherwise.

By signing up, you agree to our User Agreement and Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement . This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

By Jia Tolentino

By Isaac Chotiner

By Jessica Winter

Read our research on: Abortion | Podcasts | Election 2024

Regions & Countries

Key facts about the abortion debate in america.

The U.S. Supreme Court’s June 2022 ruling to overturn Roe v. Wade – the decision that had guaranteed a constitutional right to an abortion for nearly 50 years – has shifted the legal battle over abortion to the states, with some prohibiting the procedure and others moving to safeguard it.

As the nation’s post-Roe chapter begins, here are key facts about Americans’ views on abortion, based on two Pew Research Center polls: one conducted from June 25-July 4 , just after this year’s high court ruling, and one conducted in March , before an earlier leaked draft of the opinion became public.

This analysis primarily draws from two Pew Research Center surveys, one surveying 10,441 U.S. adults conducted March 7-13, 2022, and another surveying 6,174 U.S. adults conducted June 27-July 4, 2022. Here are the questions used for the March survey , along with responses, and the questions used for the survey from June and July , along with responses.

Everyone who took part in these surveys is a member of the Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. This way nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. Read more about the ATP’s methodology .

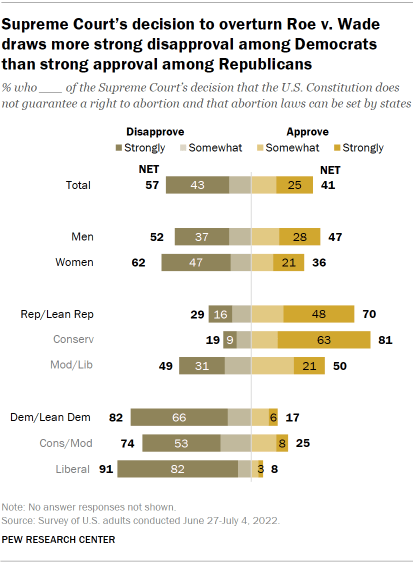

A majority of the U.S. public disapproves of the Supreme Court’s decision to overturn Roe. About six-in-ten adults (57%) disapprove of the court’s decision that the U.S. Constitution does not guarantee a right to abortion and that abortion laws can be set by states, including 43% who strongly disapprove, according to the summer survey. About four-in-ten (41%) approve, including 25% who strongly approve.

About eight-in-ten Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents (82%) disapprove of the court’s decision, including nearly two-thirds (66%) who strongly disapprove. Most Republicans and GOP leaners (70%) approve , including 48% who strongly approve.

Most women (62%) disapprove of the decision to end the federal right to an abortion. More than twice as many women strongly disapprove of the court’s decision (47%) as strongly approve of it (21%). Opinion among men is more divided: 52% disapprove (37% strongly), while 47% approve (28% strongly).

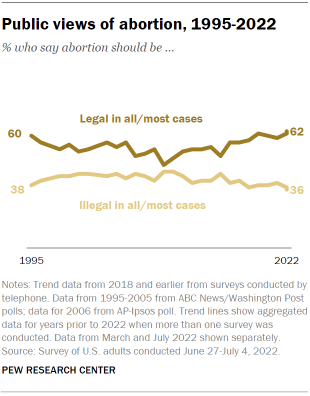

About six-in-ten Americans (62%) say abortion should be legal in all or most cases, according to the summer survey – little changed since the March survey conducted just before the ruling. That includes 29% of Americans who say it should be legal in all cases and 33% who say it should be legal in most cases. About a third of U.S. adults (36%) say abortion should be illegal in all (8%) or most (28%) cases.

Generally, Americans’ views of whether abortion should be legal remained relatively unchanged in the past few years , though support fluctuated somewhat in previous decades.

Relatively few Americans take an absolutist view on the legality of abortion – either supporting or opposing it at all times, regardless of circumstances. The March survey found that support or opposition to abortion varies substantially depending on such circumstances as when an abortion takes place during a pregnancy, whether the pregnancy is life-threatening or whether a baby would have severe health problems.

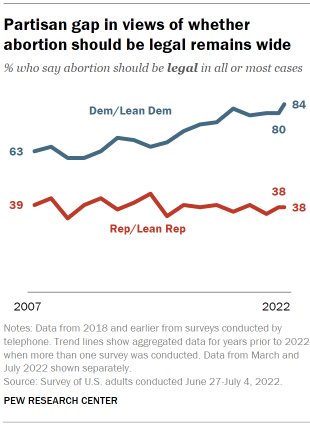

While Republicans’ and Democrats’ views on the legality of abortion have long differed, the 46 percentage point partisan gap today is considerably larger than it was in the recent past, according to the survey conducted after the court’s ruling. The wider gap has been largely driven by Democrats: Today, 84% of Democrats say abortion should be legal in all or most cases, up from 72% in 2016 and 63% in 2007. Republicans’ views have shown far less change over time: Currently, 38% of Republicans say abortion should be legal in all or most cases, nearly identical to the 39% who said this in 2007.

However, the partisan divisions over whether abortion should generally be legal tell only part of the story. According to the March survey, sizable shares of Democrats favor restrictions on abortion under certain circumstances, while majorities of Republicans favor abortion being legal in some situations , such as in cases of rape or when the pregnancy is life-threatening.

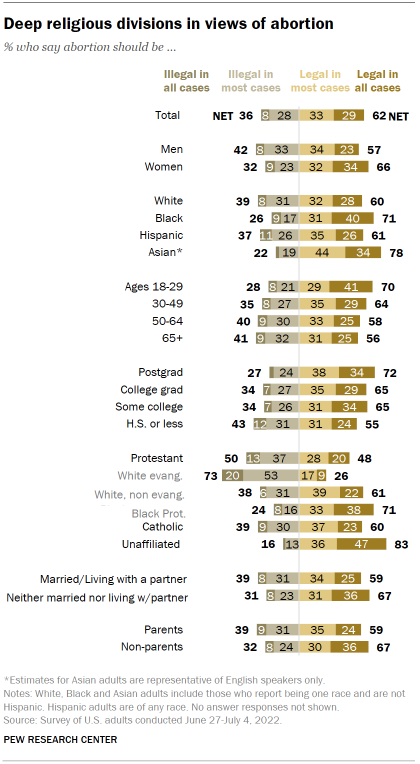

There are wide religious divides in views of whether abortion should be legal , the summer survey found. An overwhelming share of religiously unaffiliated adults (83%) say abortion should be legal in all or most cases, as do six-in-ten Catholics. Protestants are divided in their views: 48% say it should be legal in all or most cases, while 50% say it should be illegal in all or most cases. Majorities of Black Protestants (71%) and White non-evangelical Protestants (61%) take the position that abortion should be legal in all or most cases, while about three-quarters of White evangelicals (73%) say it should be illegal in all (20%) or most cases (53%).

In the March survey, 72% of White evangelicals said that the statement “human life begins at conception, so a fetus is a person with rights” reflected their views extremely or very well . That’s much greater than the share of White non-evangelical Protestants (32%), Black Protestants (38%) and Catholics (44%) who said the same. Overall, 38% of Americans said that statement matched their views extremely or very well.

Catholics, meanwhile, are divided along religious and political lines in their attitudes about abortion, according to the same survey. Catholics who attend Mass regularly are among the country’s strongest opponents of abortion being legal, and they are also more likely than those who attend less frequently to believe that life begins at conception and that a fetus has rights. Catholic Republicans, meanwhile, are far more conservative on a range of abortion questions than are Catholic Democrats.

Women (66%) are more likely than men (57%) to say abortion should be legal in most or all cases, according to the survey conducted after the court’s ruling.

More than half of U.S. adults – including 60% of women and 51% of men – said in March that women should have a greater say than men in setting abortion policy . Just 3% of U.S. adults said men should have more influence over abortion policy than women, with the remainder (39%) saying women and men should have equal say.

The March survey also found that by some measures, women report being closer to the abortion issue than men . For example, women were more likely than men to say they had given “a lot” of thought to issues around abortion prior to taking the survey (40% vs. 30%). They were also considerably more likely than men to say they personally knew someone (such as a close friend, family member or themselves) who had had an abortion (66% vs. 51%) – a gender gap that was evident across age groups, political parties and religious groups.

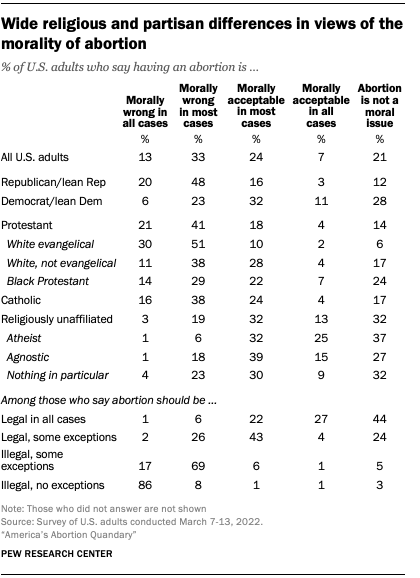

Relatively few Americans view the morality of abortion in stark terms , the March survey found. Overall, just 7% of all U.S. adults say having an abortion is morally acceptable in all cases, and 13% say it is morally wrong in all cases. A third say that having an abortion is morally wrong in most cases, while about a quarter (24%) say it is morally acceptable in most cases. An additional 21% do not consider having an abortion a moral issue.

Among Republicans, most (68%) say that having an abortion is morally wrong either in most (48%) or all cases (20%). Only about three-in-ten Democrats (29%) hold a similar view. Instead, about four-in-ten Democrats say having an abortion is morally acceptable in most (32%) or all (11%) cases, while an additional 28% say it is not a moral issue.

White evangelical Protestants overwhelmingly say having an abortion is morally wrong in most (51%) or all cases (30%). A slim majority of Catholics (53%) also view having an abortion as morally wrong, but many also say it is morally acceptable in most (24%) or all cases (4%), or that it is not a moral issue (17%). Among religiously unaffiliated Americans, about three-quarters see having an abortion as morally acceptable (45%) or not a moral issue (32%).

Sign up for our weekly newsletter

Fresh data delivered Saturday mornings

Public Opinion on Abortion

Majority in u.s. say abortion should be legal in some cases, illegal in others, three-in-ten or more democrats and republicans don’t agree with their party on abortion, partisanship a bigger factor than geography in views of abortion access locally, most popular.

About Pew Research Center Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

Persuasive Essay Guide

Persuasive Essay About Abortion

Crafting a Convincing Persuasive Essay About Abortion

-9248.jpg&w=640&q=75)

People also read

A Comprehensive Guide to Writing an Effective Persuasive Essay

200+ Persuasive Essay Topics to Help You Out

Learn How to Create a Persuasive Essay Outline

30+ Free Persuasive Essay Examples To Get You Started

Read Excellent Examples of Persuasive Essay About Gun Control

How to Write a Persuasive Essay About Covid19 | Examples & Tips

Learn to Write Persuasive Essay About Business With Examples and Tips

Check Out 12 Persuasive Essay About Online Education Examples

Persuasive Essay About Smoking - Making a Powerful Argument with Examples

Are you about to write a persuasive essay on abortion but wondering how to begin?

Writing an effective persuasive essay on the topic of abortion can be a difficult task for many students.

It is important to understand both sides of the issue and form an argument based on facts and logical reasoning. This requires research and understanding, which takes time and effort.

In this blog, we will provide you with some easy steps to craft a persuasive essay about abortion that is compelling and convincing. Moreover, we have included some example essays and interesting facts to read and get inspired by.

So let's start!

- 1. How To Write a Persuasive Essay About Abortion?

- 2. Persuasive Essay About Abortion Examples

- 3. Examples of Argumentative Essay About Abortion

- 4. Abortion Persuasive Essay Topics

- 5. Facts About Abortion You Need to Know

How To Write a Persuasive Essay About Abortion?

Abortion is a controversial topic, with people having differing points of view and opinions on the matter. There are those who oppose abortion, while some people endorse pro-choice arguments.

It is also an emotionally charged subject, so you need to be extra careful when crafting your persuasive essay .

Before you start writing your persuasive essay, you need to understand the following steps.

Step 1: Choose Your Position

The first step to writing a persuasive essay on abortion is to decide your position. Do you support the practice or are you against it? You need to make sure that you have a clear opinion before you begin writing.

Once you have decided, research and find evidence that supports your position. This will help strengthen your argument.

Check out the video below to get more insights into this topic:

Step 2: Choose Your Audience

The next step is to decide who your audience will be. Will you write for pro-life or pro-choice individuals? Or both?

Knowing who you are writing for will guide your writing and help you include the most relevant facts and information.

Paper Due? Why Suffer? That's our Job!

Step 3: Define Your Argument

Now that you have chosen your position and audience, it is time to craft your argument.

Start by defining what you believe and why, making sure to use evidence to support your claims. You also need to consider the opposing arguments and come up with counter arguments. This helps make your essay more balanced and convincing.

Step 4: Format Your Essay

Once you have the argument ready, it is time to craft your persuasive essay. Follow a standard format for the essay, with an introduction, body paragraphs, and conclusion.

Make sure that each paragraph is organized and flows smoothly. Use clear and concise language, getting straight to the point.

Step 5: Proofread and Edit

The last step in writing your persuasive essay is to make sure that you proofread and edit it carefully. Look for spelling, grammar, punctuation, or factual errors and correct them. This will help make your essay more professional and convincing.

These are the steps you need to follow when writing a persuasive essay on abortion. It is a good idea to read some examples before you start so you can know how they should be written.

Continue reading to find helpful examples.

Persuasive Essay About Abortion Examples

To help you get started, here are some example persuasive essays on abortion that may be useful for your own paper.

Short Persuasive Essay About Abortion

Persuasive Essay About No To Abortion

What Is Abortion? - Essay Example

Persuasive Speech on Abortion

Legal Abortion Persuasive Essay

Persuasive Essay About Abortion in the Philippines

Persuasive Essay about legalizing abortion

You can also read m ore persuasive essay examples to imp rove your persuasive skills.

Examples of Argumentative Essay About Abortion

An argumentative essay is a type of essay that presents both sides of an argument. These essays rely heavily on logic and evidence.

Here are some examples of argumentative essay with introduction, body and conclusion that you can use as a reference in writing your own argumentative essay.

Abortion Persuasive Essay Introduction

Argumentative Essay About Abortion Conclusion

Argumentative Essay About Abortion Pdf

Argumentative Essay About Abortion in the Philippines

Argumentative Essay About Abortion - Introduction

Abortion Persuasive Essay Topics

If you are looking for some topics to write your persuasive essay on abortion, here are some examples:

- Should abortion be legal in the United States?

- Is it ethical to perform abortions, considering its pros and cons?

- What should be done to reduce the number of unwanted pregnancies that lead to abortions?

- Is there a connection between abortion and psychological trauma?

- What are the ethical implications of abortion on demand?

- How has the debate over abortion changed over time?

- Should there be legal restrictions on late-term abortions?

- Does gender play a role in how people view abortion rights?

- Is it possible to reduce poverty and unwanted pregnancies through better sex education?

- How is the anti-abortion point of view affected by religious beliefs and values?

These are just some of the potential topics that you can use for your persuasive essay on abortion. Think carefully about the topic you want to write about and make sure it is something that interests you.

Check out m ore persuasive essay topics that will help you explore other things that you can write about!

Tough Essay Due? Hire Tough Writers!

Facts About Abortion You Need to Know

Here are some facts about abortion that will help you formulate better arguments.

- According to the Guttmacher Institute , 1 in 4 pregnancies end in abortion.

- The majority of abortions are performed in the first trimester.

- Abortion is one of the safest medical procedures, with less than a 0.5% risk of major complications.

- In the United States, 14 states have laws that restrict or ban most forms of abortion after 20 weeks gestation.

- Seven out of 198 nations allow elective abortions after 20 weeks of pregnancy.

- In places where abortion is illegal, more women die during childbirth and due to complications resulting from pregnancy.

- A majority of pregnant women who opt for abortions do so for financial and social reasons.

- According to estimates, 56 million abortions occur annually.

In conclusion, these are some of the examples, steps, and topics that you can use to write a persuasive essay. Make sure to do your research thoroughly and back up your arguments with evidence. This will make your essay more professional and convincing.

Need the services of a professional essay writing service ? We've got your back!

MyPerfectWords.com is a persuasive essay writing service that provides help to students in the form of professionally written essays. Our persuasive essay writer can craft quality persuasive essays on any topic, including abortion.

Frequently Asked Questions

What should i talk about in an essay about abortion.

When writing an essay about abortion, it is important to cover all the aspects of the subject. This includes discussing both sides of the argument, providing facts and evidence to support your claims, and exploring potential solutions.

What is a good argument for abortion?

A good argument for abortion could be that it is a woman’s choice to choose whether or not to have an abortion. It is also important to consider the potential risks of carrying a pregnancy to term.

Write Essay Within 60 Seconds!

Caleb S. has been providing writing services for over five years and has a Masters degree from Oxford University. He is an expert in his craft and takes great pride in helping students achieve their academic goals. Caleb is a dedicated professional who always puts his clients first.

Paper Due? Why Suffer? That’s our Job!

Keep reading

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Guest Essay

The Supreme Court Got It Wrong: Abortion Is Not Settled Law

By Melissa Murray and Kate Shaw

Ms. Murray is a law professor at New York University. Ms. Shaw is a contributing Opinion writer.

In his majority opinion in the case overturning Roe v. Wade, Justice Samuel Alito insisted that the high court was finally settling the vexed abortion debate by returning the “authority to regulate abortion” to the “people and their elected representatives.”

Despite these assurances, less than two years after Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, abortion is back at the Supreme Court. In the next month, the justices will hear arguments in two high-stakes cases that may shape the future of access to medication abortion and to lifesaving care for pregnancy emergencies. These cases make clear that Dobbs did not settle the question of abortion in America — instead, it generated a new slate of questions. One of those questions involves the interaction of existing legal rules with the concept of fetal personhood — the view, held by many in the anti-abortion movement, that a fetus is a person entitled to the same rights and protections as any other person.

The first case , scheduled for argument on Tuesday, F.D.A. v. Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine, is a challenge to the Food and Drug Administration’s protocols for approving and regulating mifepristone, one of the two drugs used for medication abortions. An anti-abortion physicians’ group argues that the F.D.A. acted unlawfully when it relaxed existing restrictions on the use and distribution of mifepristone in 2016 and 2021. In 2016, the agency implemented changes that allowed the use of mifepristone up to 10 weeks of pregnancy, rather than seven; reduced the number of required in-person visits for dispensing the drug from three to one; and allowed the drug to be prescribed by individuals like nurse practitioners. In 2021, it eliminated the in-person visit requirement, clearing the way for the drug to be dispensed by mail. The physicians’ group has urged the court to throw out those regulations and reinstate the previous, more restrictive regulations surrounding the drug — a ruling that could affect access to the drug in every state, regardless of the state’s abortion politics.

The second case, scheduled for argument on April 24, involves the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act (known by doctors and health policymakers as EMTALA ), which requires federally funded hospitals to provide patients, including pregnant patients, with stabilizing care or transfer to a hospital that can provide such care. At issue is the law’s interaction with state laws that severely restrict abortion, like an Idaho law that bans abortion except in cases of rape or incest and circumstances where abortion is “necessary to prevent the death of the pregnant woman.”

Although the Idaho law limits the provision of abortion care to circumstances where death is imminent, the federal government argues that under EMTALA and basic principles of federal supremacy, pregnant patients experiencing emergencies at federally funded hospitals in Idaho are entitled to abortion care, even if they are not in danger of imminent death.

These cases may be framed in the technical jargon of administrative law and federal pre-emption doctrine, but both cases involve incredibly high-stakes issues for the lives and health of pregnant persons — and offer the court an opportunity to shape the landscape of abortion access in the post-Roe era.

These two cases may also give the court a chance to seed new ground for fetal personhood. Woven throughout both cases are arguments that gesture toward the view that a fetus is a person.

If that is the case, the legal rules that would typically hold sway in these cases might not apply. If these questions must account for the rights and entitlements of the fetus, the entire calculus is upended.

In this new scenario, the issue is not simply whether EMTALA’s protections for pregnant patients pre-empt Idaho’s abortion ban, but rather which set of interests — the patient’s or the fetus’s — should be prioritized in the contest between state and federal law. Likewise, the analysis of F.D.A. regulatory protocols is entirely different if one of the arguments is that the drug to be regulated may be used to end a life.

Neither case presents the justices with a clear opportunity to endorse the notion of fetal personhood — but such claims are lurking beneath the surface. The Idaho abortion ban is called the Defense of Life Act, and in its first bill introduced in 2024, the Idaho Legislature proposed replacing the term “fetus” with “preborn child” in existing Idaho law. In its briefs before the court, Idaho continues to beat the drum of fetal personhood, insisting that EMTALA protects the unborn — rather than pregnant women who need abortions during health emergencies.

According to the state, nothing in EMTALA imposes an obligation to provide stabilizing abortion care for pregnant women. Rather, the law “actually requires stabilizing treatment for the unborn children of pregnant women.” In the mifepristone case, advocates referred to fetuses as “unborn children,” while the district judge in Texas who invalidated F.D.A. approval of the drug described it as one that “starves the unborn human until death.”

Fetal personhood language is in ascent throughout the country. In a recent decision , the Alabama Supreme Court allowed a wrongful-death suit for the destruction of frozen embryos intended for in vitro fertilization, or I.V.F. — embryos that the court characterized as “extrauterine children.”

Less discussed but as worrisome is a recent oral argument at the Florida Supreme Court concerning a proposed ballot initiative intended to enshrine a right to reproductive freedom in the state’s Constitution. In considering the proposed initiative, the chief justice of the state Supreme Court repeatedly peppered Nathan Forrester, the senior deputy solicitor general who was representing the state, with questions about whether the state recognized the fetus as a person under the Florida Constitution. The point was plain: If the fetus was a person, then the proposed ballot initiative, and its protections for reproductive rights, would change the fetus’s rights under the law, raising constitutional questions.

As these cases make clear, the drive toward fetal personhood goes beyond simply recasting abortion as homicide. If the fetus is a person, any act that involves reproduction may implicate fetal rights. Fetal personhood thus has strong potential to raise questions about access to abortion, contraception and various forms of assisted reproductive technology, including I.V.F.

In response to the shifting landscape of reproductive rights, President Biden has pledged to “restore Roe v. Wade as the law of the land.” Roe and its successor, Planned Parenthood v. Casey, were far from perfect; they afforded states significant leeway to impose onerous restrictions on abortion, making meaningful access an empty promise for many women and families of limited means. But the two decisions reflected a constitutional vision that, at least in theory, protected the liberty to make certain intimate choices — including choices surrounding if, when and how to become a parent.

Under the logic of Roe and Casey, the enforceability of EMTALA, the F.D.A.’s power to regulate mifepristone and access to I.V.F. weren’t in question. But in the post-Dobbs landscape, all bets are off. We no longer live in a world in which a shared conception of constitutional liberty makes a ban on I.V.F. or certain forms of contraception beyond the pale.

Melissa Murray, a law professor at New York University and a host of the Supreme Court podcast “ Strict Scrutiny ,” is a co-author of “ The Trump Indictments : The Historic Charging Documents With Commentary.”

Kate Shaw is a contributing Opinion writer, a professor of law at the University of Pennsylvania Carey Law School and a host of the Supreme Court podcast “Strict Scrutiny.” She served as a law clerk to Justice John Paul Stevens and Judge Richard Posner.

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

How rightwing groups used junk science to get an abortion case before the US supreme court

Anti-abortion researchers ‘exaggerate’ and ‘obfuscate’ in their scientific papers – but by the time they’re published, it’s too late

- Explainer: the mifepristone case

- Tell us: have you used an abortion pill in the US?

A pharmacy professor who strenuously avoids heated political discussions is an unlikely candidate to get involved in a fight over abortion, particularly one as high stakes as a case now before the supreme court: the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) v the Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine (AHM).

But when the professor Chris Adkins of South University in Georgia emailed his concerns about an academic article to the editors of Health Services Research and Managerial Epidemiology, that’s exactly what happened.

The article had been published by an anti-abortion research institute and, perhaps unsurprisingly, concluded that medication abortion was far less safe than the accepted scientific consensus – one established by more than 100 peer-reviewed studies across multiple continents and two decades of real-world use.

“The way this study used this situation to exaggerate, and I’ll say obfuscate, the truth behind mifepristone’s safety profile is where I thought: ‘I’ll reach out to the journal and say I’ve got these issues,’” said Adkins, referring to the drug targeted by researchers. Mifepristone is one half of a two-pill regimen that treats miscarriage and ends early pregnancy, and its future hangs in the balance of the supreme court case, to be heard this week.

“I honestly didn’t think I would be the first to do that,” said Adkins.

Within a couple days of Adkins’ complaint, the global academic publisher Sage, which publishes the journal, began investigating. Within weeks, Sage retracted not one but three papers by the anti-abortion researchers .

Adkins’ concerns go to the heart of a problem that has bedeviled scientists for at least a decade: the judicial system’s repeated adoption of poor-quality evidence to justify litigation and legislation to restrict abortion. Often that evidence is produced by the anti-abortion movement itself.

FDA v AHM is scheduled for oral arguments on Tuesday. The suit, brought by anti-abortion doctors, seeks to force the FDA to reverse decisions that relaxed restrictions on prescribing mifepristone. The Biden administration and the medication’s manufacturer argue the doctors have no right to sue in the first place.

The study Adkins complained about is central to the doctors’ case, and was cited heavily by a federal district court in Amarillo, Texas, that kicked off the government’s appeal when it found in favor of anti-abortion doctors.

How the supreme court decides the case could have profound implications. A finding in favor of anti-abortion doctors could reshape abortion access again in the US, including in Democratic-led states that might have considered themselves immune from restrictions. It also holds the potential to upend the FDA’s authority, which could call into question the future of all kinds of controversial drugs, from contraception to vaccines to treatments for HIV.

Researchers are skeptical that Sage’s retractions alone will make a difference in the court’s decision.

“It’s frustrating, it’s depressing, it’s maddening and quite honestly it’s frightening,” said the obstetrician and gynecologist Daniel Grossman of the University of California at San Francisco (UCSF).

Grossman is also a professor and the director of Advancing New Standards in Reproductive Health , one of the nation’s foremost reproductive health research groups. His own work has been taken out of context by attorneys arguing to restrict abortion in court briefs, he said, and he has published pieces to criticize the poor quality of evidence produced by anti-abortion doctors and researchers.

“Judges don’t have expertise to be able to review the science, just like I don’t have all the expertise to understand all the legal maneuvering that’s happening in this case,” said Grossman.

The anti-abortion movement pours money into research groups such as the Charlotte Lozier Institute, whose raison d’ être is to produce articles its activists can cite in litigation, legislation and promotional materials. The institute was founded in 2011 by one of the nation’s most powerful anti-abortion advocacy groups, Susan B Anthony Pro-life America, and its researchers are responsible for the three now-retracted articles flagged by Adkins.

Mary Ziegler, a professor of law at the University of California at Davis and a leading legal historian of the abortion debate, says the movement has spent decades investing in its own research arm. Campaigners started fringe publications, such as the journal Issues in Law and Medicine, a peer-reviewed publication produced by the the National Legal Center for the Medically Dependent and Disabled. That organization was founded by James Bopp , a lawyer who has campaigned against abortion for decades, and is now the lead council of the National Right to Life.

The journal’s current editor , Barry Bostrom, is an attorney who fought abortion for decades. Bostrom has served as director and general counsel of Indiana Right to Life , and at least once represented National Right to Life before the Federal Election Commission in 2009, alongside Bopp.

But “that’s not the business model anymore”, Ziegler said. The movement is no longer limiting anti-abortion research to its own journals.

after newsletter promotion

Now, anti-abortion researchers also seek to place their research in journals published by academic publishers such as Sage or, in another example, the British Journal of Psychiatry, published by the Royal College of Psychiatrists.

In the latter example, an American researcher found that abortion accounts for a substantial increase of risk in adverse mental health outcomes. However, the researcher’s analysis depended in part on a “debunked” paper, overestimated risk and did not follow published guidelines for the kind of analysis performed.

Researchers have repeatedly raised concerns to the British Journal of Psychiatry and even recently published an article in the British Medical Journal (BMJ) calling for a retraction. So far, they have been rebuffed by British psychiatrists.

In spite of their efforts, the researcher’s work has been repeatedly cited as evidence of the harms of abortion before state courts and federal courts. In 2022, the researchers’ work was cited in a brief to the supreme court in Dobbs v Jackson Women’s Health Organization, the case that ended nearly 50 years of constitutional protection for abortion. The anti-abortion movement has also used the researcher as an expert witness in court .

But fighting poor-quality evidence can feel like a losing battle. Responding in a well-respected journal can be a lengthy process that doesn’t always pay off.

Ushma Upadhyay, a public health social scientist trained in demography, and a professor in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at UCSF, contributed to both the BMJ article that failed to secure a retraction, and co-authored an article in the journal Contraception with Adkins on the flaws in the now-retracted Sage articles.

“We worked on it over Thanksgiving break. My mom was visiting, and I was like: ‘I’m really sorry, we have to get this out,’” said Upadhyay. “The stakes were so high.”

Evaluating scientific evidence is difficult under the best of circumstances. To the untrained eye, academic journals are a thicket of unknown quality, and “peer review” is a lofty term but is only as strong as the people doing the reviewing.

Even when researchers make a compelling case, journals can be loath to correct the scientific record . That allows a contested article to be further cited and compounds the damage of poor evidence..

“For every one paper that is retracted, there are probably 10 that should be,” Ivan Oransky, co-founder of Retraction Watch, recently told the New York Times. Retraction Watch maintains a database of more than 47,000 retracted studies.

Should the court choose to undermine the FDA, it will be the result of a tragic irony – that one of the world’s most respected arbiters of science could be undone by research that would never meet its standards.

- Peer review and scientific publishing

- US supreme court

- Medical research

- Reproductive rights

Most viewed

- Newsletters

- Account Activating this button will toggle the display of additional content Account Sign out

The Fight Against Birth Control Is Already Here

Conservatives are using old methods to start the battle against contraceptives..