Common Module Cheat Sheet - All Texts

Download a printable version here., module description.

In this common module students deepen their understanding of how texts represent individual and collective human experiences. They examine how texts represent human qualities and emotions associated with, or arising from, these experiences. Students appreciate, explore, interpret, analyse and evaluate the ways language is used to shape these representations in a range of texts in a variety of forms, modes and media.

Students explore how texts may give insight into the anomalies, paradoxes and inconsistencies in human behaviour and motivations, inviting the responder to see the world differently, to challenge assumptions, ignite new ideas or reflect personally. They may also consider the role of storytelling throughout time to express and reflect particular lives and cultures. By responding to a range of texts they further develop skills and confidence using various literary devices, language concepts, modes and media to formulate a considered response to texts.

Students study one prescribed text and a range of short texts that provide rich opportunities to further explore representations of human experiences illuminated in texts. They make increasingly informed judgements about how aspects of these texts, for example context, purpose, structure, stylistic and grammatical features, and form shape meaning. In addition, students select one related text and draw from personal experience to make connections between themselves, the world of the text and their wider world.

Key Statements

Dimensions of the human experience.

The human experiences represented in your prescribed/unseen texts will always be connected to one of the subcategories of the “wellness wheel”:

Words to include in textual analysis

These make markers happy for some reason.

- Appreciate - when making a judgement about the value of something

- Explore - when discussing the themes of the text

- Interpret - when discussing the audience’s interaction with the text

- Analyse - When discussing your understanding of the text

- Expression - When discussing the author/poet/artist’s connection to the text

- Elicit - When discussing how a technique results in an emotion

Plutchik Wheel of Emotions

Essay length.

For paper 1 unseen texts, a good estimate is 2-3 lines per mark, while the extended response should be ~800 words/6 pages. If you don’t hit those numbers, that’s totally fine, it’s just a good estimate.

RESOURCE: CHIPS Question Breakdown Strategy

Body paragraph structure.

- Statement about the concept

- What type(s) of experience from the wellness wheel is represented, and is it collective or individual?

- What emotions from the Plutkich wheel are present, and how are they used (Example/Technique from PETAL paragraphs)?

- How does the experience of the example present anomaly/paradox/inconsistency in the human experience?

- Personal reflection? Challenging the reader’s assumptions? Persuading you of something?

- Conclude with a mash of steps 1, 2, and 3

Positive and Negative Words

Words to describe the human experience that mean nothing but for some reason get more marks, targets of a text, punchy phrases.

- Aids in this improved understanding of the textual material

- Indicates the universality in the subject matter being contemplated

- Brings reader to consider more deeply the manner in which ___

- An intimacy is generated between the viewer and ___

- Creates a more nuanced understanding

- Attracting to the audience to both ___

- To further impress upon the reader the idea of ___

- Further clarify and cement reader’s understand of the literal content

- Further elucidates the impression that

Free Thesis Statements

- Texts represent how human experiences are dependent on one’s context and their ability to transcend the limitations of context

- Texts about human experience invite the audience to contemplate on their own experiences and reflect on the processes that shape their identity

- Human experiences may be recursive but they are transformative nonetheless

- Texts offer a representations of human experience that challenges our assumptions and thus intensifies our awareness of self and others

- Representation of relationships in texts highlight the way in which human experiences may differ in varied interactions

- Texts offer a representation of the human experience to record the social and emotional development of the individual and the collective

- Our experiences expose our capacity for fortitude and focus, particularly when our individual ideals are challenged by contextual values / societal expectations

Last updated on November 17, 2021

How to achieve a Band 6 in the HSC English exam

by Gabby | HSC ENGLISH

There are several areas that are necessary to master in order to perform a high score in the NESA HSC English exams. Let’s see them one by one.

Common Module – What are the underlying assumptions about the human experience?

How do the texts in your comprehension section explore the collective and individual experiences which shape human behaviour and the moral and ethical choices available?

Reading Task

Firstly, try to identify the purpose of the text whilst reading: is it designed to satirise, mock, convey or promote a particular idea? (Remember all forms of texts are ultimately persuasive in nature)

When reading the articles, remember to orientate yourselves:

- Look at the title, consider and predict what the article might be about – by guessing you are already thinking and engaging and this will facilitate your comprehension.

- Look at the beginning and end of the text; this is where you can often discover the purpose.

- As you read be on the look-out for techniques, which you can deconstruct.

- Do not answer a question which asks how the idea is expressed by simply saying “using descriptive or emotive language”. You need to explain what literary or poetic devices are used e.g. simile, metaphor, hyperbole etc.

Answering all these questions requires you to understand the conditions and contexts which contribute to the human experience and how effectively they are communicated! To answer ‘effectively’ requires you to cite the techniques e.g. – the use of register, tone, word choice and symbolism.

Section II of the Common Module paper requires you to write an essay. As the Common Module texts have been in place for quite a number of years, examiners are no doubt tired of predictive responses or, worse still, pre-learned essays. These can come across as a little tired and lacking an edge in original thought and depth. Don’t see the question as an impediment to your rote-learned response, rather look at what the question is asking. The depth of response can be formulated by considering the assumptions that underscore the very nature of the question itself:

- Why has the examiner chosen this question?

- Is this really what the writer was trying to communicate?

Modules A and B

Both HSC Advanced English modules require your understanding of how the composer’s context and his or her audience informs on our understanding of the text. This must be established in your essay.

For example, Hamlet may well be a Prince torn between the Renaissance values of his world and his belief in the church, and of course Shakespeare’s audience would have understood this; but what about us as a contemporary audience? What ideas in the text find resonance in our world today?

Be sure to consider not only how the contexts of each composer have given rise to the ideas of the core texts but also why they are studied side by side. How might the concerns of previous historical and cultural contexts find relevance still today? For example:

- Are any of Virginia Woolf’s concerns echoed in ‘The Hours’ (despite in the shifting contexts)? If so, why?

- Are any of Shakespeare’s concerns echoed in ‘Looking for Richard’ (despite in the shifting contexts)? If so, why?

Consider the integrity of the text. This refers to the components, which have allowed the text to stand the test of time. Ideas, language features and other poetic, dramatic or literary devices are part of what allows the text to retain its integrity. The context of the composer and his or her audience informs on our understanding of the text.

- Module C: The Craft of Writing

In this section of the exam, you’ll be asked to write on a creative discursive or persuasive piece of writing. Please refer to my blog entitled ‘ Module C: The Craft of Writing How to write a creative writing piece ’ .

One of the harder aspects for many students is to reflect on the textual inspiration they have received from their set text. You may wish to consider how your set text expresses some of these features:

- Register and tone

- Intertextual referencing

- Symbolism and figurative language

- Stream of consciousness

These features are some that you may wish to adopt in your own creative presentation.

Preparing for the HSC English Exams

Learn the ways you can express features of language and know how to identify them e.g. personification, sibilance, metaphor, simile etc.

Write several essays for the Common Module (human experience), Module A and Module B; consider writing on those topics that might otherwise confuse you.

Many students write notes and study quotes – but you still need to know how to formulate an essay. Look at as many questions as you can and, rather than simply making notes, write the essays.

Try and tackle difficult questions so as not to fall into the trap of writing generic essays, as you believe they can be better manipulated to the suit the question. The real exercise is whether you can apply your knowledge to any question, and if you don’t practice you won’t know.

Answering questions on any essay topic

Consider the following:

- How accurately does the question reflect the ideas at the core of the text?

- Is the question provocative in nature or does it simply require corroboration or a rejection of the thesis set down? For example: sometimes questions require your weighing up of the author’s intention, his or her ideas and the way they’re expressed.

- Questions that ask you to discuss are generally straightforward and, whilst requiring you to discuss the topic at hand, may still require that you negate the thesis postulated.

- Many questions ask your opinion. This is no different to any other question as your thesis is exactly what you think – do not answer the question with ‘I think’ as what you think is already assumed. The question is asked as many students rely too heavily on critical theorists without having determined their own opinion.

- The most important consideration in any essay (and the feature that separates an average response from a more advanced one) is why . Why has the composer explored the ideas at hand? Too many students focus on what the ideas are and how they are represented. Including why should yield a relationship between the writer’s world of imagination and their context.

The Essay structure for all modules

Your introduction should be concise but have a clear thesis (an argument) which sets out your response to the question and hopefully includes what, why and how the author/film director has imparted his or her ideas.

“What” would probably reflect the ideas at the core of the text. “Why” should most likely include the composer’s context, and “how” should refer to the features of language or cinematic techniques used. Each paragraph should aim to answer the question preferably in the opening of the paragraph as this is the initial impression formed by markers.

The topic sentence (opening sentence) should incorporate the theme or idea of your paragraph whilst at the same time answering the question at hand. The more often you link back to your thesis and to the question, the more comprehensive and succinct your essay will appear.

Pitfalls in exams

- Do not story-tell – provide evidence! Too many students use the plot as a way to advance their arguments. We know the plot; you need to provide the purpose and evidence. Commence your sentence starters with verb of purpose. The writer: conveys, portrays, dismantles, questions or satirises. In this way, you will be forced to advance an opinion rather than a rehashing of the plot.

- Many students forget to watch the time. You cannot afford to go over the set time. Forty minutes per question.

- Underline the key parts of the question.

- Sometimes a word may throw you off in an exam. Remember: you know more than you think from the context. You know if it’s a noun, verb or an adjective. All these skills should help you discern the meaning of the word.

- Always consider the beginning and end of your text and the way it informs on the text as a whole.

More stumbling blocks

Terms that often confuse students.

- “Dramatic features” refers to soliloquies, dramatic irony, characterisation, plot, language and symbolism.

- “Narrative style” refers to the way the text is composed.

- “Consider the narrative style ” refers to how it reflects the ideas and often the context underscoring the text, e.g. Virginia Woolf’s text – witty, exploratory, and satiric. Her narrative style often shifts to a stream of consciousness, which challenges the conventional writing styles of her time.

Using critical theorists and material

All knowledge is useful but you must first determine your own understanding – always providing support from the text. Once you have determined your own opinion you may use critical theorists to either affirm your view or as a springboard to offer an alternate perspective. It is refreshing for examiners to read ideas which may be different – as long as they can be substantiated.

Textual referencing

This is essential to any essay and the quotes chosen must enable you to not only cite an example, but convey the way meaning is shaped! Remember that in deconstructing meaning, you must not write about the linguistic or cinematic techniques as if they were in a vacuum – but instead as part of your ability to add to your understanding and the power of the text. Consider the following:

- Don’t just cite the technique as a metaphor or simile when deconstructing your evidence or if writing about a film, or writing about a long shot on screen; explain why and how it contributes to meaning.

- Consider why a particular aspect of your text moves you; the chances are, it is the way it is expressed.

- Draw from the whole text – don’t restrict your answers to the beginning or end of a text.

All Modules require an understanding of the correlation between representation and meaning.

Put simply: how is the text represented (the techniques or images used) and what kind of meaning is imparted?

Students must understand that the English Syllabus has been influenced by postmodern understanding in its inception and so the relationship between representation and meaning has to be examined.

Representation refers to the way a writer or speaker represents a personality, event, or idea. This representation is clearly tied up with:

- The nuanced nature of language itself and the slippery nature of symbolism (slippery as symbolism may impart a myriad of interpretations).

- Our own cultural interpretation and the ‘signification’ we bring to language.

- The textual medium itself – (film, novel or autobiography) and its power of persuasion.

Meaning is difficult to establish, as it is largely dependent on how we interpret the representation of an event, personality, or concept (namely, our perspective).

Meaning will be influenced by:

- The credibility and authority of the perspective advanced

- The bias and prejudice the composer brings to his or her representation

- The bias and prejudice we bring to the perspective on offer

- The cultural and normative values that not only consciously and unconsciously influence the speaker or composer but our own cultural points of reference.

Recent Posts

- How to write an HSC Advanced English Common Module essay?

- Othello – C.C. (Santa Sabina)

- Plath & Hughes – R.P. (James Ruse)

- An Artist of the Floating World – A.W. (Sydney Grammar)

Recent Comments

You cannot copy content of this page

NOW OPEN: 2024 Term Two Enrolments 🎉

A State Ranker’s Guide to Writing 20/20 English Advanced Essays

I completed 4 units of English, so take it from me, I've written lots of essays!

Marko Beocanin

99.95 ATAR & 3 x State Ranker

1. Introduction to this Guide

Essays can be tough. Like, really tough.

They’re made tougher still because every HSC English module has a different essay structure, and no-one seems to have a consistent idea of what an ‘ essay’ actually is (not to get postmodern on you!).

My name is Marko Beocanin, and I’m an English tutor at Project Academy. In this post I hope to demystify essay-writing and arm you with a “tried and proven” approach you can apply to any essay you’ll write in HSC English and beyond. In 2019, I completed all four units of English (Extension 2, Extension 1, and Advanced), and state ranked 8th in NSW for English Advanced and attained a 99.95 ATAR – so take it from me, I’ve written a lot of essays! Here’s some of the advice I’ve picked up throughout that experience.

2. My Essay-Writing Methodology

For us to understand how to write an essay, it’s important to appreciate what an essay (in particular, a HSC English essay) actually is. I’ve come to appreciate the following definition:

An essay is a structured piece of writing that argues a point in a clear, sophisticated way *, and expresses* personality and flair.

Let’s have a look at each of these keywords – and how they should inform our essay-writing process – in more detail.

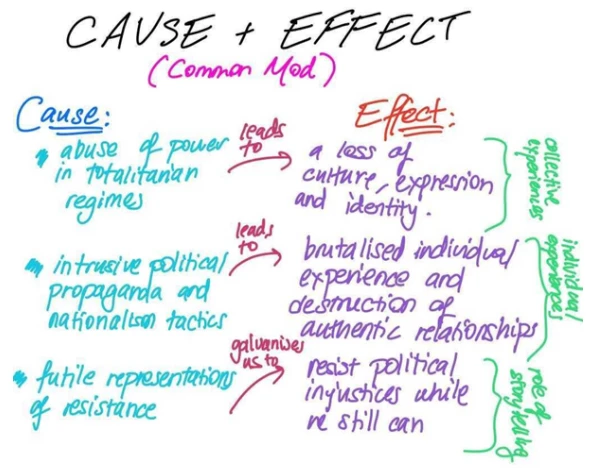

3. “Arguing a point” means CAUSE and EFFECT

When most people study English, they tend to make huge lists of Themes, Values, Concerns, Quotes and so on. While this is a great exercise for collecting evidence and understanding your texts, it’s important to remember that your essay is not simply a theme summary or quote bank – you have to actually argue something!

And any argument needs a cause and an effect.

When you approach any essay question, it’s not enough to simply chuck in quotes/topic-sentences that abstractly relate to it. An internal checklist you could go through while reading a question might look like:

What is the question actually asking me?

What is my response to the question?

Am I actually making an argument in my response, and not just repeating the question?

What is my cause?

What is my effect?

How can I prove my argument?

It’s only at question 4 that quotes/analysis/topic-sentences appear. Your first step in writing any essay is to actually have an argument to prove.

Cause and Effect in Thesis Statements

To demonstrate what I mean by cause-and-effect, let’s have a look at a lower-band essay thesis on Nineteen Eighty-Four:

In Nineteen Eighty-Four, George Orwell explores totalitarianism.

This sentence is a flat declaration of a theme. While it does identify totalitarianism, it doesn’t give any indication on what parts of totalitarianism Orwell explores, and what the actual effect of totalitarianism is.

In Nineteen Eighty-Four, George Orwell explores the abuse of power in totalitarian regimes.

This one is certainly better, because it describes a specific element of totalitarianism that Orwell explores – but it’s still missing an actual argument about what totalitarianism DOES to people. A full cause and effect (and higher band) thesis statement might look like:

In Nineteen Eighty-Four, George Orwell explores how the abuse of power in totalitarian regimes leads to a brutalised human experience.

This thesis explicitly outlines how the CAUSE (abuse of power in totalitarian regimes) leads to the EFFECT (a brutalised human experience).

There’s certainly still some ambiguity in this sentence – for example, what sort of human experiences are being brutalised? – and in an exam, you’d substitute that for the specific human experiences outlined in the question.

In general, whenever you see sentences like “Composer X discusses Theme Y” in your essay drafts, think about developing them into “Composer X discusses how Specific Cause of Theme Y leads to Specific Effect of Theme Y”.

Cause and Effect Diagrams

To make sure that your arguments actually have a specific cause and effect , try writing them out in the following diagrammatic way:

_Surprisingly, drawing the arrow made a huge psychological difference for me! _

If you struggle with this, try to restructure/rephrase your arguments until they can be categorised in such a way. Making and rewriting these diagrams is also a great way to prep for exams without writing out your whole essay.

Cause and Effect in Analysis

Similarly, when it comes to your actual analysis itself, make sure that you’re not just listing techniques and quotes. You’re not just analysing your quotes for the sake of naming the techniques in them – you’re analysing them to prove a point!

Whenever you consider a quote for your essay, ask yourself:

What is this quote about?

How does this quote prove my argument?

How do the literary techniques in this quote prove my argument?

Let’s use an example from King Henry IV, Part 1 to illustrate this. A lower band piece of analysis might look like:

King Henry’s opening monologue employs anthropomorphism: “Daub her lips with her own children’s blood…bruise her flow’rets with…armed hoofs.”

While the technique of anthropomorphism is identified, this sentence doesn’t link to any argument about WHY that technique is there and what it does.

King Henry’s opening monologue anthropomorphises England as a mother violated by war: “Daub her lips with her own children’s blood…bruise her flow’rets with…armed hoofs.”

This is certainly better, because it explains what the technique actually does – but it still doesn’t discuss how the technique guides us to an actual point.

King Henry’s opening monologue anthropomorphises England as a mother violated by war: “Daub her lips with her own children’s blood…bruise her flow’rets with…armed hoofs…” to convey the civil unrest caused by his tenuous claim to the throne.

This analysis not only outlines the technique in detail, but it also explicitly embeds it with an argument – this time, structured as EFFECT ( civil unrest ) caused by CAUSE ( his tenuous claim to the throne ).

In general, whenever you see analysis in your drafts written as “Composer X uses Technique Y in Quote Z”, try to rewrite it as “Composer X uses Technique Y in Quote Z to argue Point A”.

4. Clear, Sophisticated Way

In general, clarity/sophistication in Advanced essays comes from two main sources.

Essay Structure

For most essays, the simplest and most effective overall structure looks like:

Intro: Here, you answer the question with an argument, summarise your points and link to the rubric.

3 – 4 Body Paragraphs: Here, you actually make your points.

Conclusion: Here, you re-summarise your arguments and ‘drop the mic’.

While it’s cool to play around with the number of body paragraphs, for example, the structure above is generally a safe bet for Advanced.

The most variety comes from the actual structure within your body paragraphs.

There are plenty of online guides/resources with fun acronyms like STEEL and PEETAL and less fun ones like PEEQTET – but ultimately, the exact formula you go with is a relatively inconsequential matter of choice and style. Just make sure you have the following elements roughly in this order!

Cause and Effect Topic Sentence

Here, you make your point as clearly as possible (remember cause and effect), and address the specific argument that the paragraph will cover. It’s fantastic if you can link this argument to the argument in your previous paragraph.

Context Sentence

This bit is vital (and often forgotten!). Texts don’t exist in a void – their composers had lives, were influenced by the world around them, and had inspirations and purposes in their compositions. Context can be political, socio-cultural, religious, philosophical, literary etc… as long as it’s there!

Cause and Effect Analysis

In a three-paragraph structure, a solid aim is for four to five quotes per paragraph. Each point you make should be justified with a quote, and each quote should have a technique linked to it. It’s usually helpful to order your quotes chronologically as they appear within the text (to show how the argument progressively builds) – but in more non-linear forms like poetry, for example, you can switch it up a little. Make sure each paragraph covers quotes from the whole text, to demonstrate a broad range of analysis!

Here, you might give a restatement of your topic sentence that summarises your main ideas.

Wording and Expression

A common misconception with English Advanced is that huge words and long, meandering sentences will score the most marks.

In Advanced, clarity should come from your expression , while sophistication should come from your ideas . Ultimately, the more complex your expression and sentence structure is, the more your markers will have to work to connect with your content.

While an occasional well-executed piece of technical jargon is impressive, it should never come at the cost of clearly and explicitly getting your point across.

A few general tips I’ve picked up from both my time as a student and my work as a tutor include:

Avoid using a thesaurus/online synonym-search whenever possible! If you didn’t consider using a word naturally, it’s unlikely it will flow with the rest of your expression.

A long, comma-intensive sentence can (and should) almost always be replaced with two or more sentences.

Use semicolons sparingly (if at all), and with GREAT caution.

Never underestimate words like “because”, “leads to”, “causes” etc. They are simple, but brilliantly effective at establishing a clear cause and effect structure!

Make sure to continuously reuse words from the question. Even if this feels clunky, it helps you actually engage with the question.

Also make sure to continuously use rubric keywords – particularly in Common Mod and Mod A!

5. Personality and Flair

And now… the hardest bit. Putting a bit of you into your essays.

There’s no one way to “add personality/flair” – this is where you have the freedom to develop your own voice and style. Remember that your markers love literature – and for them to see real, unadulterated enthusiasm in your work is an absolute win that will be marked generously.

To develop that passionate flair/personality, I encourage you to do three things:Practice. A Lot. The more you write – whether it’s homework questions, mini paragraphs, or flat-out full practice essays – the better you’ll become at writing. It’s as simple as that.

6. Concluding Remarks

Get feedback on your work..

To make sure you’re actually improving with your writing, aim to get plenty of feedback from both of these groups:

People who know your text and HSC English in-and-out (teachers, tutors, scholars etc.), so they can engage with your analysis and help develop your style/structure.

People who don’t know your texts and HSC English particularly well (parents, friends, etc.), so they can check your arguments actually make sense!

Explore your own English-related interests.

Reading widely and writing weird stuff just for fun adds an indescribable but very real level of depth and nuance to your essay-writing. For me, this involved immersing myself in crazy literary theory that had nothing to with my texts, and writing super edgy poetry. Find what works for you!

Good Luck!!!

Whether this article reaches you the night before Paper 1, or at the start of your English journey – I’m confident that you can do this. If you can find even one thing that you connect with about this subject… whether it’s a character you love, or a beautiful poem, or a wacky critical piece that’s totally BS… hopefully you’ll realise that essay writing doesn’t have to be so tough after all!

Maximise Your Chances Of Coming First At School

Trial any Project Academy course for 3 weeks.

NSW's Top 1% Tutors

Unlimited Tutorials

NSW's Most Effective Courses

Access to Project's iPad

Access to Exclusive Resources

Access to Project's Study Space

How I achieved a 99.65 ATAR and Got Into Medicine

The bigges misconception that I often hear students say about the HSC is that...

Xerxes Lopes

All-Rounder & 99.65 ATAR

Achieving 3 State Ranks, a perfect 99.95 ATAR and being School Captain

At times, Year 12 was the last lap of Mario Kart’s Rainbow Road – where the...

How I Achieved 3rd in NSW for 3U Maths and a 99.80 ATAR

I’m here to pass on the strategies I used to achieve my goal ATAR of 99.80 an...

Laura Hardy

State Ranker & 99.85 ATAR

Achieving Two State Ranks, Dux and a 99.95 ATAR

I’d be lying if I told you that I enjoyed sitting my HSC...

Cory Aitchison

State Ranker & 99.95 ATAR

- OC Test Preparation

- Selective School Test Preparation

- Maths Acceleration

- English Advanced

- Maths Standard

- Maths Advanced

- Maths Extension 1

- English Standard

- English Common Module

- Maths Standard 2

- Maths Extension 2

- Business Studies

- Legal Studies

- UCAT Exam Preparation

Select a year to see available courses

- Level 7 English

- Level 7 Maths

- Level 8 English

- Level 8 Maths

- Level 9 English

- Level 9 Maths

- Level 9 Science

- Level 10 English

- Level 10 Maths

- Level 10 Science

- VCE English Units 1/2

- VCE Biology Units 1/2

- VCE Chemistry Units 1/2

- VCE Physics Units 1/2

- VCE Maths Methods Units 1/2

- VCE English Units 3/4

- VCE Maths Methods Units 3/4

- VCE Biology Unit 3/4

- VCE Chemistry Unit 3/4

- VCE Physics Unit 3/4

- Castle Hill

- Strathfield

- Sydney City

- Inspirational Teachers

- Great Learning Environments

- Proven Results

- OC Test Guide

- Selective Schools Guide

- Reading List

- Year 6 English

- NSW Primary School Rankings

- Year 7 & 8 English

- Year 9 English

- Year 10 English

- Year 11 English Standard

- Year 11 English Advanced

- Year 12 English Standard

- Year 12 English Advanced

- HSC English Skills

- How To Write An Essay

- How to Analyse Poetry

- English Techniques Toolkit

- Year 7 Maths

- Year 8 Maths

- Year 9 Maths

- Year 10 Maths

- Year 11 Maths Advanced

- Year 11 Maths Extension 1

- Year 12 Maths Standard 2

- Year 12 Maths Advanced

- Year 12 Maths Extension 1

- Year 12 Maths Extension 2

- Year 11 Biology

- Year 11 Chemistry

- Year 11 Physics

- Year 12 Biology

Year 12 Chemistry

- Year 12 Physics

- Physics Practical Skills

- Periodic Table

- NSW High Schools Guide

- NSW High School Rankings

- ATAR & Scaling Guide

- HSC Study Planning Kit

- Student Success Secrets

- 1300 008 008

- Book a Free Trial

Ultimate Guide for How to Answer Common Module Unseen Questions

In this post, we give you the ultimate breakdown for acing the Common Module unseen questions for Texts and Human Experiences.

Get free study tips and resources delivered to your inbox.

Join 75,893 students who already have a head start.

" * " indicates required fields

You might also like

- 2017 HSC Chemistry Exam Paper Solutions (with Option Topics)

- Jason’s UMAT Hacks: How I got 100th Percentile in UMAT

- The Essential Guide to Textual Integrity

- Module B: Understanding Henry IV Part 1 – Overview | Free Exemplar Response

- 2015 HSC Chemistry Worked Solutions (Multiple Choice)

Related courses

Year 12 common module study guides, year 12 business studies, year 12 pdhpe, year 12 legal studies, ucat preparation course.

Do you struggle with unseen texts?

Do you always run out of time in for comprehension questions?

Do you know what your responses are meant to look like?

In this post, we will show you how to prepare for and ace the HSC Common Module Paper 1 Short Response Questions.

What skills do I need to ace the Paper 1 unseen questions?

Section 1 of Paper 1 tests a few different things:

- Comprehension skills

- Textual analysis skills

- Knowledge of the Common Module: Texts and Human Experiences

- Ability to write clear and concise responses

Want to put your skills to the test?

You can download the paper with unseen texts and then we’ll send you sample responses along with marking criteria 24 hours later.

Comprehension Skills

You need to be able to quickly read questions and unseen texts to construct responses

You need to be able to quickly analyse unseen texts. It is not enough to be able to spot superficial techniques in a text. Matrix students learn how to analyse unseen texts for higher order techniques and understand how these are developing the themes and ideas in the texts.

To succeed in Paper 1, you need to be able to do a quick analysis and then connect this analysis to the concerns and ideas that you have studied in the Common Module.

If you need help getting on top of your textual analysis skills, you should read our Beginner’s Guide to Acing HSC English Part 1: How to Analyse Your English Texts for Evidence .

Knowledge of the Common Module: Texts and Human Experiences rubric

If you want to write insightful responses to the Paper 1 unseen questions, then you need to have a detailed knowledge and understanding of the Common Module: Texts and Human Experiences rubric.

If you are unsure of what the Module is about or want to get a detailed understanding of it, then you must read our Year 12 English Advanced Study Guide article .

Students are often unsure of what they need to do when writing a response to unseen sections. How much do you need to write? How little?

When answering short answer questions, clarity and concision are key.

In fact, more important than the length is the quality and concision of the writing. Matrix students learn how to produce erudite and insightful responses that clearly relate their ideas and answers to the questions with supporting evidence.

What’s the structure of the Common Module HSC Paper 1?

Let’s look at the structure of Paper 1:

English Advanced Paper 1 has two sections:

- short response questions

- long response or essay section

The short response questions will involve 3-4 unseen texts and a series of 4 or 5 questions. This section will be worth 20 marks.

You will have 10 minutes reading time and 45 minutes writing time to complete each section.

How long are the texts that I have to read for the unseen section?

That will depend.

In previous HSC Paper 1 exams, the length of the unseen texts has varied significantly. In some years, students have had no trouble reading all of the unseen texts, but in others, such as the 2018 HSC, students have struggled to complete the reading in the allocated time.

In the sample 2019 Paper 1 provided by NESA , for example, there are a pair of posters, a 30 line poem, a 536-word non-fiction piece, a 983-word non-fiction piece, and a longer extract from a fiction text.

The length of the unseen texts is a significant challenge that you must account for in your preparation and exam strategy. We’ll discuss the strategies Matrix students use later in this post.

These questions will total 20 marks, one question will require a miniature essay for a response. Students will need to allocate a little over 2 minutes per mark when responding to questions.

How do I study for the Common Module Paper 1 Exam?

As we discussed above, the skills you need are:

But how do you develop and hone these skills?

Practise and feedback!

English is not an innate skill.

Successful English skills are developed through a consistent reading, an ongoing study practice, and regular writing and feedback cycle.

If you want to be able to approach your next unseen paper with a swagger, you need to practice unseen sections before-hand and get feedback on your responses.

So, how do I practise analysing unseen texts?

You need to find short texts online and practice reading them and analysing against a timer.

A good process for doing this is to find texts that are similar in media, form, and length to previous HSC unseen texts and try to identify the main ideas and themes and a set number of examples within a few minutes.

This is actually quite a challenging task, especially the first few times that you try it.

To develop these skills try the following:

- Pick a text of the appropriate length and type

- Give yourself 10 minutes on a timer

- Set yourself a target of, say, 2 themes/ideas and 5 techniques to identify

- Analyse the text to the timer and underline notate the examples you find

- Check your answers

- Try it again on a similar timer, but with only 7.5 minutes on a timer

- Keep practising until you can comfortably analyse a text in 2-3 minutes.

How should I practise my short answer responses?

The skills you need to write a good short answer response are developed through practice and feedback.

Your peers who consistently get full marks for their unseen sections do so because they practise writing responses and get feedback on how to improve them and make them more concise and efficient. All conscientious English Advanced students should be scoring Band 6 for their unseen responses, if not full marks.

To practise your unseen responses, do the following:

- Get your hands on a practice paper. You can find past Area of Study: Discovery papers here on the NESA website or, even better, try your skills on our Matrix English Advanced Common Module Practice Paper 1 .

- Set yourself a timer for 65 minutes. Allow 15 minutes reading time and 50 minutes writing time.

- Attempt the paper.

- Mark your responses against the marking rubrics and exemplar responses provided or get feedback from your teacher or peers

- Find another practice paper and attempt that, working to a shorter time limit.

Want to ace English?

Book your free English Trial Lesson today. Join over 4500 students who already have a head start in English over their peers. Book your free trial lesson .

Structuring a short response answer

One of the most common questions that students have about short responses is how long their responses should be.

The length of your responses will vary depending on how many marks the question is worth and how much time you can allocate to it.

For example, a three mark question is only worth 7 minutes of your time. So, you’re only going to be able to produce about 100-200 words at most (people tend to average about 13-31 words per minute by hand) in that amount of time depending on your handwriting. You need to keep your writing legible, too. It’s no point bashing out an amazing 210-word response if nobody can read it. Your marks would be better off with something much shorter and more legible.

You want to aim for one example and explanation per mark on offer. For example, if you have a two mark question, provide two examples and analysis of those examples.

The extended short response question

The final question for the short response questions is usually worth between 6 and 7 marks and requires a miniature essay in response. The question can ask you to discuss one text or several. It is important that you structure your response accordingly.

This means you need a brief introduction , a body paragraph or two, and a brief conclusion .

Your introduction needs to briefly introduce your chosen text(s) and their relevance to the question. Try to include terms or phrases from the Common Module rubric in your thesis, as this will directly address the module concerns. You should keep your introduction under two sentences.

Your body needs to expand on these ideas. It is important that you use topic sentences to introduce your ideas.

If you must discuss two texts, you need to choose between writing a divided (a paragraph on each text) or integrated response (discussing both texts in one paragraph). Whichever structure you choose, you need to present two or three examples from each text and discuss them in detail.

If the question asks you to contrast or compare the texts, you must discuss the texts in relation to each other.

This will usually entail discussing how one text represents an aspect of human experience or emotion more effectively than another. Ensure that you relate your examples to the question, don’t just list technique, example, and effect.

Finally, your conclusion must summarise the argument, relating it back to the question and Common Module. Make sure that you restate your thesis. Aim for at least one sentence, if not two.

Answering a short response question

To get a sense of what you should include in a short response answer, let’s consider one of the NESA sample questions from their mock 2019 paper .

Example B (6 marks) English Standard and English Advanced Compare how Text 2 and Text 3 explore the paradoxes in the human experience.

Text 2 can be found here and Text 3 is in the NESA sample paper.

Analysing the texts

Before you can write your response, you need to analyse the texts. It is important to use the question to guide the focus of your analysis.

This question asks students to discuss the paradoxes in the human experience. This is a statement from the rubric. A paradox is a statement that seemingly contradicts itself. So our analysis of these texts needs to focus in on things that seem contradictory or logically unacceptable.

Analysing Text 2

Text 2, Vern Rustala’s “Looking in the Album,” is an ekphrastic poem. Ekphrasis is the representation of an image in prose or poetry. In this poem, the speaker describes several photographs and little aspects of each.

The poem explores how photographs can only capture a limited aspect of human experience, even though they trigger memories. The poem also discusses how photographs don’t capture all of the moments and are often carefully curated.

There are a couple of paradoxes present, here:

- Photographs capture moments of our lives and trigger authentic memories but are staged and falsified records

- Photographs don’t carry the records of our negative experiences of our lives. We often curate those out to give a “true account” of our lives.

Next, you need to find some examples that bear these paradoxes out. Because this is a 6 mark question and we have to compare two texts, we will look for two examples. One for each paradox. We will use the text’s form as our other example.

Analysing Text 3

In Text 3, Hillary McPhee explores the trouble she has in reconciling her profession as a historian with her love of her family’s stories and her grandmother’s ability to tell them.

This is an autobiographical text. It is a memoir that discusses her experience of mixing her personal and professional lives and the consequences of this.

This text discusses the conflict between wanting to know the truth about something and enjoying the romance of how it has been told.

There are a couple of paradoxes in this text as well:

- We can either know the truth about something or appreciate the romantic or mythic nature of it

- We can’t reconcile factual truths with family storytellers

Next, let’s look at some evidence. This time we’ll look at three examples, because this text’s paradoxes need a little more framing. McPhee opens with an extended metaphor that introduces the ideas:

Now we’ve got some evidence, we’re in a position to write a response.

Writing the response

Let’s look at the question again:

Example B (6 marks) English Standard and English Advanced “Compare how Text 2 and Text 3 explore the paradoxes in the human experience.”

So, this is a 6 mark question and requires us to compare the texts. This means that we need to use a miniature essay structure.

We then need to decide whether to use an integrated or divided response:

- An integrated response will allow us to be more efficient in our comparison.

- A divided response will be a little more straightforward for presenting our analysis but will require us to spend the second paragraph doing the comparison.

Your marks won’t be affected by your decision, only by the quality of your execution.

Our response will take the following structure:

Introduction : Two or three sentences outlining our response to the question and introducing the texts.

Body : An integrated response that analyses the texts and compares their representations of paradox in human experience across two paragraphs.

Conclusion : Two sentences that summarise your argument and connect it to the Module.

Okay, so what would this look like? Let’s look at the type of exemplary response a Matrix student would write.

Exemplar response

Both Hillary McPhee and Vern Rustala explore the paradoxes we find in our human experiences. Rustala’s poem, “Looking in the Album,” delves into the idiosyncrasies and paradoxes of how we curate and remember our lives. While McPhee’s biographical excerpt catalogues the paradoxes and ironies she wrestled with while trying to balance her professional self with her personal self.

Memory and the process of remembering are rich with emotional complexity and, yet, fraught with paradox. Rustala employs a free-verse poem with heavy enjambment to reflect the conflicts and paradoxes of how we catalogue and record our lives. The persona’s observation that “Here the formal times are surrendered / to the camera’s indifferent gaze” combines enjambment and personification to convey the paradox of how we remember our lives. While humans keep photographs to remember important occasions and feel nostalgia for them as it is an important part of our emotional experience, the speaker observes that we relinquish control over them to an external force – one that is insouciant about our experience or feelings. In contrast, McPhee’s biography focuses on her own experiences and evokes nostalgia in her extended metaphor that “her stories [came] like webs across the world… and her stories invaded our dreams.” As Rustala’s images are a contrived remembrance of the past, so are McPhee’s grandmother’s. Only, in contrast, McPhee ascribes these partially fictionalised accounts a positive value.

“Looking in the Album’s” speaker is troubled by how photographs alter our past and, potentially, our memories when they observe that “[w]e burned the negatives that we felt did not give a true / account and with others made this abridgement of our lives.” The pun on “negatives” conflates photographic images with the poor experiences, developing the metaphor that by destroying negatives we are trying to cleanse ourselves of negative experiences. We can find a paradox at the heart of the ironic notion of manipulating things we feel do not “give a true account” of our lives. Essentially, Rustala is suggesting that we wish to have a true record, but adulterate it to suit our feelings. McPhee struggles with a similar yet different reconciliation between the true and romanticised accounts of her Grandmother’s life. In each paragraph McPhee explores the historical facts and contrasts them to her Grandmother’s accounts, instilling doubt into the veracity of her accounts with the truncated statements “[o]r so she said.” and “[o]r so the story goes …” These caveats frame the paradox she faces: she can’t be a nostalgic granddaughter and a historian at the same time. Pursuing truth comes at the expense of nostalgia. She makes this clear when she ironically observes that “[t]he historian at the back of my brain says I should discover what is true and what is false” while “[t]he rest of me… still sees… the shapes and shadows of other places she made my own.” The contrast between these two sides of her life highlights the emotional paradoxes that can affect our lives as we try to balance professional success with emotional fulfilment and happiness, nostalgia and fact.

Human experience is emotionally complex as we try to hold onto our past while struggling with the acceptable shape it must take. The differences between McPhee’s and Ruslata’s texts highlight this struggle – pointing to how sometimes our emotional security requires us to see things as they actually happened while at others we must shroud events in myth.

Sitting the Exam

Now let’s look at some Dos and Don’ts for the unseen section of Paper 1.

Time Management

Planning your time for Paper 1 is essential. You have 1 hour 40 minutes to complete the section. That breaks down to 45 minutes per section and 10 minutes reading time.

Do read the questions first.

Then read them again. To be efficient and accurate you need to read the unseen texts with the questions in mind.

Don’t just read the texts, analyse them.

As you read look for evidence that will help you answer the questions. The questions usually ask you to address specific ideas in each text. This is done to guide you to the examples you need to collect.

Do use your maths skills to calculate how much time to allocate to answering each question.

Each mark is worth 2.25 minutes of your time. This means that for a 2 mark question you don’t want to spend more than 5 minutes answering it. By this rationale, you want to be spending about 15-16 minutes on a miniature essay worth seven marks. If you don’t finish the question in the allotted time, cut your losses and start the next one.

Don’t answer the questions in order.

Make sure you analyse the texts based on the question, so you gather evidence for all of them. But don’t begin on the lower mark questions. Get the questions worth more in the bag, first.

Do respond to the question worth the most marks, first.

Be strategic and guarantee yourself the most marks that you can. Starting with the 6 or 7 mark question guarantees you a share of those marks. If you do run out of time before finishing one or two questions from the section, it is better that those questions are only worth one or two marks rather than a third of the paper!

Analysing the Texts

Analysing texts on the fly is hard. You will need to practice this skill and ensure you are familiar with a wide range of literary and visual devices. If you need to brush up on them, we explain a comprehensive set of devices and techniques in our Essential Guide to English Techniques .

Don’t rush the reading of the unseen texts during the reading time.

Reading the questions will guide you as to how the text should be read and analysed. The questions will ask you to discuss how a composer represents a specific idea from the syllabus rubric. You want to identify that idea in the text, and note how they represent it.

Do try to identify multiple examples in each text.

Collecting as much evidence as possible on your first reading will make that easier. That way you have enough evidence to respond to several questions. You don’t have time to go back and do another reading.

Don’t get caught up in superficial analysis.

Techniques like alliteration and rhyme might have pleasing aesthetic qualities, but they are not as useful for representing concepts as metaphors or similes.

Do focus on higher order techniques.

Literary devices such as metaphor, motif, and irony over simple techniques such as alliteration. Your ability to spot higher order techniques will make analysing the texts far easier. Remember, you should practice on random short stories and poems you find on the internet.

Don’t ignore form and medium.

Your unseen texts will all have different forms. It is important that you take the time to think about how the composers’ choice of form influences meaning. Ask yourself, “what is the composer trying to achieve by utilising this form or medium?” You want to discuss this in your responses.

Answering the Questions

Do answer the questions clearly and concisely.

Ensure that you are answering the question asked. Before writing a response, reread the question to ensure that it will be a direct answer.

Don’t recount the text.

This will generally not constitute an answer to the question. Instead, respond as succinctly as possible to the question.

Do plan your responses according to their value.

As a rule, if the question is worth one mark, use at least one example and an explanation of its technique and effect. If the question is worth two marks, use at least two examples.

Don’t prioritise quantity over detail.

Remember, the markers are looking for detailed explanations of how an example represents an idea, not how many examples you can present. You need to respond to the ideas in the module. To do this effectively try to use terms and phrases from the Common Module rubric.

Written by Matrix English Team

© Matrix Education and www.matrix.edu.au, 2023. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Matrix Education and www.matrix.edu.au with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

Learning methods available

Boost your Business Studies marks and confidence with structured courses online or on-campus.

Boost your Chemistry marks and confidence with structured courses online or on-campus.

Boost your PDHPE marks and confidence with structured courses online or on-campus.

Boost your Legal Studies marks and confidence with structured courses online or on-campus.

Matrix UCAT Courses are designed to teach you the theory and exam techniques to acing the UCAT test.

Related articles

Kia’s Physics Hacks: How I Aced HSC Physics and scored a 99.15 ATAR

In this post, Kia shares her secrets for how she scored an ATAR of 99.15.

Postgraduate Medicine – An Alternate Pathway

There's more than one way to get into medicine. Curious about the options? Read on!

2019 HSC Maths Ext 2 Exam Paper Solutions

In this post, we give you the solutions to the 2019 Maths Extension 2 paper.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Example of a great essay | Explanations, tips & tricks

Example of a Great Essay | Explanations, Tips & Tricks

Published on February 9, 2015 by Shane Bryson . Revised on July 23, 2023 by Shona McCombes.

This example guides you through the structure of an essay. It shows how to build an effective introduction , focused paragraphs , clear transitions between ideas, and a strong conclusion .

Each paragraph addresses a single central point, introduced by a topic sentence , and each point is directly related to the thesis statement .

As you read, hover over the highlighted parts to learn what they do and why they work.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

Other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about writing an essay, an appeal to the senses: the development of the braille system in nineteenth-century france.

The invention of Braille was a major turning point in the history of disability. The writing system of raised dots used by visually impaired people was developed by Louis Braille in nineteenth-century France. In a society that did not value disabled people in general, blindness was particularly stigmatized, and lack of access to reading and writing was a significant barrier to social participation. The idea of tactile reading was not entirely new, but existing methods based on sighted systems were difficult to learn and use. As the first writing system designed for blind people’s needs, Braille was a groundbreaking new accessibility tool. It not only provided practical benefits, but also helped change the cultural status of blindness. This essay begins by discussing the situation of blind people in nineteenth-century Europe. It then describes the invention of Braille and the gradual process of its acceptance within blind education. Subsequently, it explores the wide-ranging effects of this invention on blind people’s social and cultural lives.

Lack of access to reading and writing put blind people at a serious disadvantage in nineteenth-century society. Text was one of the primary methods through which people engaged with culture, communicated with others, and accessed information; without a well-developed reading system that did not rely on sight, blind people were excluded from social participation (Weygand, 2009). While disabled people in general suffered from discrimination, blindness was widely viewed as the worst disability, and it was commonly believed that blind people were incapable of pursuing a profession or improving themselves through culture (Weygand, 2009). This demonstrates the importance of reading and writing to social status at the time: without access to text, it was considered impossible to fully participate in society. Blind people were excluded from the sighted world, but also entirely dependent on sighted people for information and education.

In France, debates about how to deal with disability led to the adoption of different strategies over time. While people with temporary difficulties were able to access public welfare, the most common response to people with long-term disabilities, such as hearing or vision loss, was to group them together in institutions (Tombs, 1996). At first, a joint institute for the blind and deaf was created, and although the partnership was motivated more by financial considerations than by the well-being of the residents, the institute aimed to help people develop skills valuable to society (Weygand, 2009). Eventually blind institutions were separated from deaf institutions, and the focus shifted towards education of the blind, as was the case for the Royal Institute for Blind Youth, which Louis Braille attended (Jimenez et al, 2009). The growing acknowledgement of the uniqueness of different disabilities led to more targeted education strategies, fostering an environment in which the benefits of a specifically blind education could be more widely recognized.

Several different systems of tactile reading can be seen as forerunners to the method Louis Braille developed, but these systems were all developed based on the sighted system. The Royal Institute for Blind Youth in Paris taught the students to read embossed roman letters, a method created by the school’s founder, Valentin Hauy (Jimenez et al., 2009). Reading this way proved to be a rather arduous task, as the letters were difficult to distinguish by touch. The embossed letter method was based on the reading system of sighted people, with minimal adaptation for those with vision loss. As a result, this method did not gain significant success among blind students.

Louis Braille was bound to be influenced by his school’s founder, but the most influential pre-Braille tactile reading system was Charles Barbier’s night writing. A soldier in Napoleon’s army, Barbier developed a system in 1819 that used 12 dots with a five line musical staff (Kersten, 1997). His intention was to develop a system that would allow the military to communicate at night without the need for light (Herron, 2009). The code developed by Barbier was phonetic (Jimenez et al., 2009); in other words, the code was designed for sighted people and was based on the sounds of words, not on an actual alphabet. Barbier discovered that variants of raised dots within a square were the easiest method of reading by touch (Jimenez et al., 2009). This system proved effective for the transmission of short messages between military personnel, but the symbols were too large for the fingertip, greatly reducing the speed at which a message could be read (Herron, 2009). For this reason, it was unsuitable for daily use and was not widely adopted in the blind community.

Nevertheless, Barbier’s military dot system was more efficient than Hauy’s embossed letters, and it provided the framework within which Louis Braille developed his method. Barbier’s system, with its dashes and dots, could form over 4000 combinations (Jimenez et al., 2009). Compared to the 26 letters of the Latin alphabet, this was an absurdly high number. Braille kept the raised dot form, but developed a more manageable system that would reflect the sighted alphabet. He replaced Barbier’s dashes and dots with just six dots in a rectangular configuration (Jimenez et al., 2009). The result was that the blind population in France had a tactile reading system using dots (like Barbier’s) that was based on the structure of the sighted alphabet (like Hauy’s); crucially, this system was the first developed specifically for the purposes of the blind.

While the Braille system gained immediate popularity with the blind students at the Institute in Paris, it had to gain acceptance among the sighted before its adoption throughout France. This support was necessary because sighted teachers and leaders had ultimate control over the propagation of Braille resources. Many of the teachers at the Royal Institute for Blind Youth resisted learning Braille’s system because they found the tactile method of reading difficult to learn (Bullock & Galst, 2009). This resistance was symptomatic of the prevalent attitude that the blind population had to adapt to the sighted world rather than develop their own tools and methods. Over time, however, with the increasing impetus to make social contribution possible for all, teachers began to appreciate the usefulness of Braille’s system (Bullock & Galst, 2009), realizing that access to reading could help improve the productivity and integration of people with vision loss. It took approximately 30 years, but the French government eventually approved the Braille system, and it was established throughout the country (Bullock & Galst, 2009).

Although Blind people remained marginalized throughout the nineteenth century, the Braille system granted them growing opportunities for social participation. Most obviously, Braille allowed people with vision loss to read the same alphabet used by sighted people (Bullock & Galst, 2009), allowing them to participate in certain cultural experiences previously unavailable to them. Written works, such as books and poetry, had previously been inaccessible to the blind population without the aid of a reader, limiting their autonomy. As books began to be distributed in Braille, this barrier was reduced, enabling people with vision loss to access information autonomously. The closing of the gap between the abilities of blind and the sighted contributed to a gradual shift in blind people’s status, lessening the cultural perception of the blind as essentially different and facilitating greater social integration.

The Braille system also had important cultural effects beyond the sphere of written culture. Its invention later led to the development of a music notation system for the blind, although Louis Braille did not develop this system himself (Jimenez, et al., 2009). This development helped remove a cultural obstacle that had been introduced by the popularization of written musical notation in the early 1500s. While music had previously been an arena in which the blind could participate on equal footing, the transition from memory-based performance to notation-based performance meant that blind musicians were no longer able to compete with sighted musicians (Kersten, 1997). As a result, a tactile musical notation system became necessary for professional equality between blind and sighted musicians (Kersten, 1997).

Braille paved the way for dramatic cultural changes in the way blind people were treated and the opportunities available to them. Louis Braille’s innovation was to reimagine existing reading systems from a blind perspective, and the success of this invention required sighted teachers to adapt to their students’ reality instead of the other way around. In this sense, Braille helped drive broader social changes in the status of blindness. New accessibility tools provide practical advantages to those who need them, but they can also change the perspectives and attitudes of those who do not.

Bullock, J. D., & Galst, J. M. (2009). The Story of Louis Braille. Archives of Ophthalmology , 127(11), 1532. https://doi.org/10.1001/archophthalmol.2009.286.

Herron, M. (2009, May 6). Blind visionary. Retrieved from https://eandt.theiet.org/content/articles/2009/05/blind-visionary/.

Jiménez, J., Olea, J., Torres, J., Alonso, I., Harder, D., & Fischer, K. (2009). Biography of Louis Braille and Invention of the Braille Alphabet. Survey of Ophthalmology , 54(1), 142–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.survophthal.2008.10.006.

Kersten, F.G. (1997). The history and development of Braille music methodology. The Bulletin of Historical Research in Music Education , 18(2). Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/40214926.

Mellor, C.M. (2006). Louis Braille: A touch of genius . Boston: National Braille Press.

Tombs, R. (1996). France: 1814-1914 . London: Pearson Education Ltd.

Weygand, Z. (2009). The blind in French society from the Middle Ages to the century of Louis Braille . Stanford: Stanford University Press.

If you want to know more about AI tools , college essays , or fallacies make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

- Ad hominem fallacy

- Post hoc fallacy

- Appeal to authority fallacy

- False cause fallacy

- Sunk cost fallacy

College essays

- Choosing Essay Topic

- Write a College Essay

- Write a Diversity Essay

- College Essay Format & Structure

- Comparing and Contrasting in an Essay

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

An essay is a focused piece of writing that explains, argues, describes, or narrates.

In high school, you may have to write many different types of essays to develop your writing skills.

Academic essays at college level are usually argumentative : you develop a clear thesis about your topic and make a case for your position using evidence, analysis and interpretation.

The structure of an essay is divided into an introduction that presents your topic and thesis statement , a body containing your in-depth analysis and arguments, and a conclusion wrapping up your ideas.

The structure of the body is flexible, but you should always spend some time thinking about how you can organize your essay to best serve your ideas.

Your essay introduction should include three main things, in this order:

- An opening hook to catch the reader’s attention.

- Relevant background information that the reader needs to know.

- A thesis statement that presents your main point or argument.

The length of each part depends on the length and complexity of your essay .

A thesis statement is a sentence that sums up the central point of your paper or essay . Everything else you write should relate to this key idea.

A topic sentence is a sentence that expresses the main point of a paragraph . Everything else in the paragraph should relate to the topic sentence.

At college level, you must properly cite your sources in all essays , research papers , and other academic texts (except exams and in-class exercises).

Add a citation whenever you quote , paraphrase , or summarize information or ideas from a source. You should also give full source details in a bibliography or reference list at the end of your text.

The exact format of your citations depends on which citation style you are instructed to use. The most common styles are APA , MLA , and Chicago .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Bryson, S. (2023, July 23). Example of a Great Essay | Explanations, Tips & Tricks. Scribbr. Retrieved April 15, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/academic-essay/example-essay-structure/

Is this article helpful?

Shane Bryson

Shane finished his master's degree in English literature in 2013 and has been working as a writing tutor and editor since 2009. He began proofreading and editing essays with Scribbr in early summer, 2014.

Other students also liked

How to write an essay introduction | 4 steps & examples, academic paragraph structure | step-by-step guide & examples, how to write topic sentences | 4 steps, examples & purpose, what is your plagiarism score.

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

4.13: Writing a Personal Essay

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 58288

- Lumen Learning

Learning Objectives

- Describe techniques for writing an effective personal essay

How to Write a Personal Essay

One particular and common kind of narrative essay is the personal narrative essay. Many of you have already written at least one of these – in order to get to college. The personal essay is a narrative essay focused on you. Typically, you write about events or people in your life that taught you important life lessons. These events should have changed you somehow. From this choice will emerge the theme (the main point) of your story. Then you can follow these steps:

- Once you identify the event, you will write down what happened. Just brainstorm (also called freewriting). Focus on the actual event. You do not need to provide a complete build-up to it. For example, if you are telling a story about an experience at camp, you do not need to provide readers with a history of my camp experiences, nor do you need to explain how you got there, what we ate each day, how long it lasted, etc. Readers need enough information to understand the event. So, you do not need to provide information about my entire summer if the event only lasts a couple of days.

- Use descriptions/vivid details.

- “Nothing moved but a pair of squirrels chasing each other back and forth on the telephone wires. I followed one in my sight. Finally, it stopped for a moment and I fired.”

- The verbs are all in active voice creating a sense of immediacy: moved, followed, stopped, fired.

- Passive voice uses the verb “to be” along with an action verb: had been aiming, was exhausted.

- Develop your characters. Even though the “characters” in your story are real people, your readers won’t get to know them unless you describe them, present their personalities, and give them physical presence.

- Use dialogue. Dialogue helps readers get to know the characters in your story, infuses the story with life, and offers a variation from description and explanation. When writing dialogue, you may not remember exactly what was said in the past, so be true to the person being represented and come as close to the actual language the person uses as possible. Dialogue is indented with each person speaking as its own paragraph. The paragraph ends when that person is done speaking and any following explanation or continuing action ends. (If your characters speak a language other than English, feel free to include that in your narrative, but provide a translation for your English-speaking readers.)

- Be consistent in your point of view. Remember, if it is a personal narrative, you are telling the story, so it should be in first person. Students often worry about whether or not they are allowed to use “I.” It is impossible to write a personal essay without using “I”!

- Write the story in a consistent verb tense (almost always past tense). It doesn’t work to try to write it in the present tense since it already happened. Make sure you stay in the past tense.

Sample Personal Statement

One type of narrative essay you may have reason to write is a Personal Statement.

Many colleges and universities ask for a Personal Statement Essay for students who are applying for admission, to transfer, or for scholarships.

Generally, a Personal Statement asks you to respond to a specific prompt, most often asking you to describe a significant life event, a personality trait, or a goal or principle that motivates or inspires you. Personal Statements are essentially narrative essays with a particular focus on the writer’s personal life.

The following essay was responding to the prompt: “Write about an experience that made you aware of a skill or strength you possess.” As you read, pay attention to the way the writer gets your attention with a strong opening, how he uses vivid details and a chronological narrative to tell his story, and how he links back to the prompt in the conclusion.

Sample Student Essay

Alen Abramyan Professor X English 1101-209 2/5/2013

In the Middle of Nowhere Fighting Adversity

A three-punch combination had me seeing stars. Blood started to rush down my nose. The Russian trainers quietly whispered to one another. I knew right away that my nose was broken. Was this the end of my journey; or was I about to face adversity?

Ever since I was seven years old, I trained myself in, “The Art of Boxing.” While most of the kids were out playing fun games and hanging out with their friends, I was in a damp, sweat-filled gym. My path was set to be a difficult one. Blood, sweat, and, tears were going to be an everyday occurrence.

At a very young age I learned the meaning of hard work and dedication. Most kids jumped from one activity to the next. Some quit because it was too hard; others quit because they were too bored. My father pointed this out to me on many occasions. Adults would ask my father, ” why do you let your son box? It’s such a dangerous sport, he could get hurt. My father always replied, “Everyone is going to get hurt in their lives, physically, mentally and emotionally. I’m making sure he’s ready for the challenges he’s going to face as a man. I always felt strong after hearing my father speak that way about me. I was a boy being shaped into a man, what a great feeling it was.

Year after year, I participated in boxing tournaments across the U.S. As the years went by, the work ethic and strength of character my father and coaches instilled in me, were starting to take shape. I began applying the hard work and dedication I learned in boxing, to my everyday life. I realized that when times were tough and challenges presented themselves, I wouldn’t back down, I would become stronger. This confidence I had in myself, gave me the strength to pursue my boxing career in Russia.

I traveled to Russia to compete in Amateur Boxing. Tournament after tournament I came closer to my goal of making the Russian Olympic Boxing team. After successfully winning the Kaliningrad regional tournament, I began training for the Northwest Championships. This would include boxers from St. Petersburg, Pskov, Kursk and many other powerful boxing cities.

We had to prepare for a tough tournament, and that’s what we did. While sparring one week before the tournament, I was caught by a strong punch combination to the nose. I knew right away it was serious. Blood began rushing down my face, as I noticed the coaches whispering to each other. They walked into my corner and examined my nose,” yeah, it’s broken,” Yuri Ivonovich yelled out. I was asked to clean up and to meet them in their office. I walked into the Boxing Federation office after a quick shower. I knew right away, they wanted to replace me for the upcoming tournament. “We’re investing a lot of money on you boxers and we expect good results. Why should we risk taking you with a broken nose?” Yuri Ivonovich asked me. I replied, “I traveled half-way around the world to be here, this injury isn’t a problem for me.” And by the look on my face they were convinced, they handed me my train ticket and wished me luck.

The train came to a screeching halt, shaking all the passengers awake. I glanced out my window, “Welcome to Cherepovets,” the sign read. In the background I saw a horrific skyline of smokestacks, coughing out thick black smoke. Arriving in the city, we went straight to the weigh ins. Hundreds of boxers, all from many cities were there. The brackets were set up shortly after the weigh ins. In the Super Heavyweight division, I found out I had 4 fights to compete in, each increasing in difficulty. My first match, I made sure not a punch would land; this was true for the next two fights. Winning all three 6-0, 8-0 and 7-0 respectively. It looked like I was close to winning the whole tournament. For the finals I was to fight the National Olympic Hope Champion.